SB6

Session assets

Please decide on your access

Please use the buttons below to download the presentation materials or to visit the external website where the presentation is linked. Regarding the external link, please note that Copernicus Meetings cannot accept any liability for the content and the website you will visit.

Forward to presentation link

You are going to open an external link to the presentation as indicated by the authors. Copernicus Meetings cannot accept any liability for the content and the website you will visit.

We are sorry, but presentations are only available for users who registered for the conference. Thank you.

Oral and Poster presentations and abstracts

The Data Release 3 by the Gaia mission (ESA) will not only multiply by a large factor the volume of observations, but will also add more quality and complexity. With respect to DR2, that appeared in 2018. The number of asteroids with astrometry and photometry will be multiplied by a factor >10, and data will span a longer time interval. Also, for the first time a set of reflectance spectra for several thousand asteroids will be released. Some planetary satellites and candidate new asteroids will also be included. The improvement in volume, accuracy and variety of data will add new dimensions to the contribution of Gaia to asteroid science as this will probably be the most extensive and self consistent set of visible spectra available up to know.

In this talk, we will mainly focus on the general properties of the asteroid data in DR3 (statistics on the sample) and on the improvement in astrometry with respect to DR2. Based on the results obtained from the exploitation of DR2, we will review the expected impact of DR3 in terms of improved orbits, Yarkovsky determination, prediction of asteroid occultations. The properties of asteroid spectra in DR3 will be presented in another contribution to this meeting by M. Delbo'.

How to cite: Tanga, P.: The solar system data in the forthcoming Data Release 3 by the Gaia mission of ESA: a preview, Europlanet Science Congress 2021, online, 13–24 Sep 2021, EPSC2021-263, https://doi.org/10.5194/epsc2021-263, 2021.

How to cite: Delbo, M., Galluccio, L., De Angeli, F., Tanga, P., Cellino, A., Pauwels, T., and Mignard, F.: Gaia spectroscopic view of the asteroid main belt and beyond, Europlanet Science Congress 2021, online, 13–24 Sep 2021, EPSC2021-112, https://doi.org/10.5194/epsc2021-112, 2021.

How to cite: Dziadura, K., Oszkiewicz, D., Spoto, F., and Bartczak, P.: Yarkovsky drift detectability using the Gaia DR2 asteroid astrometry , Europlanet Science Congress 2021, online, 13–24 Sep 2021, EPSC2021-132, https://doi.org/10.5194/epsc2021-132, 2021.

Asteroids, along with other small bodies are what is left of the original planetesimal disk from the planet-formation era. But not all asteroids that we observe today are planetesimals. Many of those planetesimals, during the history of the solar system, were destroyed by impacts, creating families of smaller asteroid fragments, which make the vast majority of the current main belt population. However, very few of these collisional fragments are actually linked to known families. The smaller are the sizes of the family members, the more numerous they are. Moreover, due to non-gravitational forces, known as the Yarkovsky effect, the members of these families move away from the original location with a velocity proportional to 1/D, where D is the asteroid diameter. These two facts result in that the smaller are the studied asteroids the more confusing is the picture of the original compositional distribution.

Our team developed a novel methodology to identify the planetesimals in the main belt (Bolin et al., 2017, Delbo' et al., 2017, 2019, 2021), based on finding asteroid families from correlations between their 1/Diameter and their semi-major axis (this is the so-called V-shape of asteroid families). By removing all asteroids that are inside these V-shapes and thus belong to families, we revealed the planetesimal population. This new analysis has now been completed in the Inner Main Belt (IMB) between 2.1 and 2.5 au with the identification of 71 planetesimals.

We started a spectroscopic survey of the identified IMB planetesimals, aiming at constraining their composition and mineralogy, information that is of paramount importance for defining the original compositional gradient of the main belt, including that of materials of high exobiological interest, such as hydrated minerals and carbonaceous compounds.

The survey was mainly carried out at the 1.82m Copernico Telescopio (Asiago, Italy) for spectroscopy in the visible range, and at the 4.2m Lowell Discovery Telescope (Flagstaff, USA) and 3.2m NASA Infrared Telescope Facility (Mauna Kea, USA) for the near infrared range (0.95-2.3 micron). Few data come from unpublished observations at the 3.6m New Technology Telescope (La Silla, Chile) and the 1.22m telescope in Asiago made previously by our team. The new data presented here come from 14 distinct observing runs spread out between 1999 and 2020.

To complete the survey of the IMB planetesimals, we also used spectra in the visible and NIR range published in the literature. In fact, several of the identified planetesimals are relatively large and bright, and already studied in spectroscopy.

After standard spectral reduction procedures, we merged the visible and near-infrared spectra (when available) of a given target to obtain a full VIS+NIR spectrum and we perform the taxonomic classification following the Bus-DeMeo taxonomy (Bus et al., 2002; DeMeo et al., 2009) using the M4AST tool (http://m4ast.imcce.fr) (Popescu et al., 2012). A visual inspection to identified the presence of absorption bands characteristic of some classes was performed to strength the taxonomic classification. In addition, we compute for each planetesimal several spectral parameters, such as spectral slopes, and center, depth and minimum of absorption bands, when present. Finally, we used the RELAB database (Pieters, 1983), to look for meteorite analogues of each planetesimal.

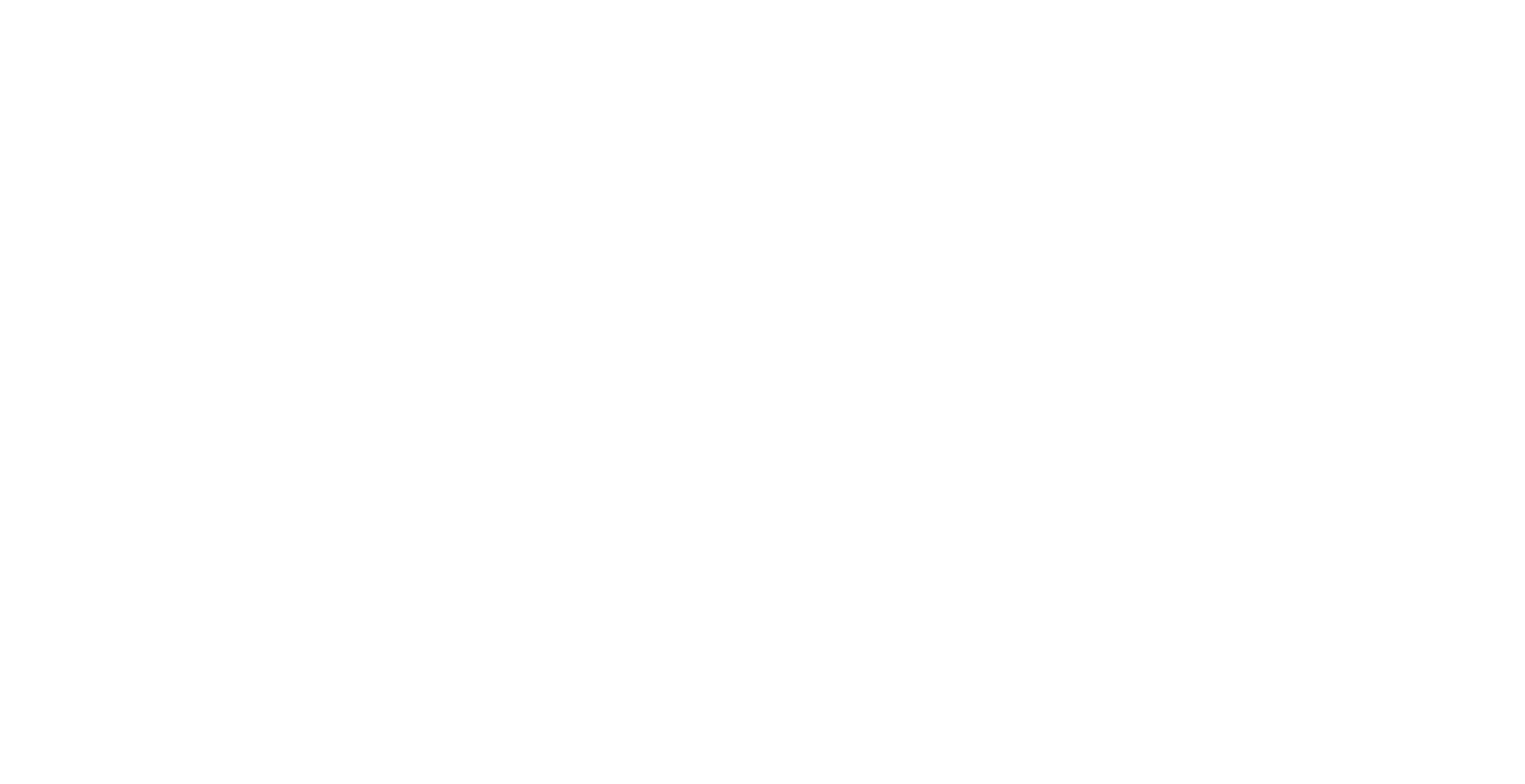

As expected, we found that the majority of the IMB planetesimals belongs to the S-complex (about 50 %, Fig. 1). The population also includes 20% of X-complex, 18 % to C-complex and 12% of end members (D, K, L and V-type). Interestingly, our survey reveals that more than 60% of the IMB carbonaceous-rich planetesimals belong to the Ch/Cgh types, as they show features associated to hydrated materials, indicating the presence of water ice at relatively small heliocentric distances. Surprisingly, about 4% of the planetesimals belong to the D-type, which are usually located in the outer Main Belt and in the Jupiter Trojan swarms. Finally, no olivine-rich A-type planetesimal is found. A-types are supposed to be formed by the collisional exposure of a mantle of a differentiated parent body. The fact that they are absent in the IMB planetesimal population supports the aforementioned theory of the A-type origin.

Here we will present the spectroscopic and compositional results of the IMB planetesimals as well as the implications for planetary formation models.

Figure 1 : The spectroscopic distribution of the studied planetesimals using the Bus-DeMeo taxonomy.

References : Bryce T. Bolin et al., Icarus, Volume 282, 2017, Pages 290-312 ; Marco Delbo et al., Science : 1026-1029, 2017 ; Marco Delbo et al., A&A 624 A69 (2019) ; Schelte J. Bus et al., Icarus, Volume 158, Issue 1, 2002, Pages 146-177 ; Francesca E. DeMeo et al., Icarus, Volume 202, Issue 1, 2009, Pages 160-180 ; M. Popescu et al., A&A 544 A130 (2012) ; Pieters, C. M. (1983), J. Geophys. Res., 88( B11), 9534– 9544,

How to cite: Bourdelle de Micas, J., Fornasier, S., Delbo, M., Avdellidou, C., and Van Belle, G.: A survey of Inner Main Belt planetesimals : composition and mineralogy, Europlanet Science Congress 2021, online, 13–24 Sep 2021, EPSC2021-198, https://doi.org/10.5194/epsc2021-198, 2021.

Asteroids are the remnant blocks of the early stages of the formation of our Solar System. In particular, those classified as “primitive” are believed to contain the most pristine and almost unprocessed materials (water-bearing minerals, carbon compounds, and organics), and therefore they provide unique information on the formation and evolution of our planetary system, including how water appeared on Earth. Among these objects, primitive near-Earth asteroids (NEAs) are of particular interest. Due to their proximity they are impact hazards to Earth, but they are also the ideal targets for space missions. That is the case of primitive NEAs (101955) Bennu and (162173) Ryugu, primary targets of NASA’s OSIRIS-REx and JAXA’s Hayabusa 2 sample return missions, respectively, currently on their way to encounter the two asteroids. The main asteroid belt, located between the orbits of Mars and Jupiter (2.1-5.2 AU), and in particular collisional families, are currently considered the principal source of NEAs (Bottke et al. 2002; Bottke et al. 2005). In the case of the two primitive NEAs mentioned above, several studies have shown that the most likely source is the Polana collisional family (Campins et al. 2010, 2013), a primitive family located in the inner belt. Other large primitive families in that region are Erigone, Sulamitis, and Clarissa. Smaller primitives families like Klio, Chaldaea, Svea and Chimaera can also be found in the same region (Nesvorny et al. 2015).

With the main objective of supporting the science return of OSIRIS-Rex and Hayabusa 2, in 2010 our group started a coordinated effort to characterize the surface composition of primitive asteroids not only in the collisional families of the inner belt, but in the central and outer belt: our PRIMitive Asteroids Spectroscopic Survey (PRIMASS) includes both visible and near-infrared spectra. Up to now, in the frame of PRIMASS, our group has studied several primitive families wihtin the inner main belt: the Polana-Eulalia complex (de León et al. 2016; Pinilla-Alonso et al. 2016), Erigone (Morate et al. 2016), Sulamitis and Clarissa (Morate et al. 2018a), and Klio, Chaldaea, Chimaera, and Svea (Morate et al. 2019). One interesting result was that Erigone. Sulamitis, Klio, Chaldaea, and Chimaera, presented different percentages of asteroids with an absorption band centered at 0.7μm and associated to hydrated silicates, while the Polana, Clarissa, and Svea families showed no signs of hydration. This result remarks the need for spectral characterization as even the families classified all a priori as primitive can show compositional differences.

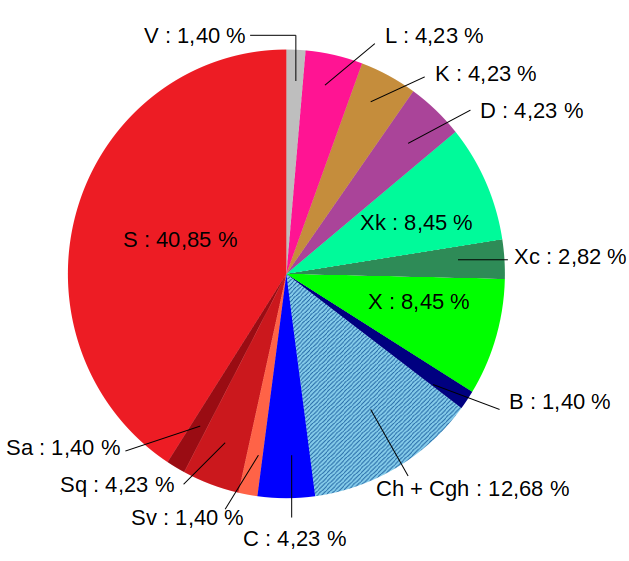

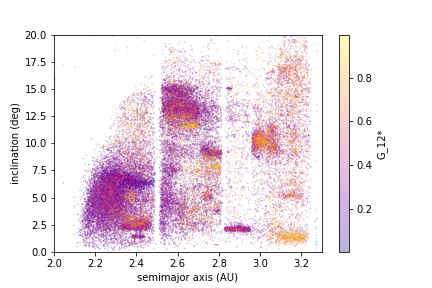

Continuing with our PRIMASS survey, we started the characterization of the families in the central part of the belt (2.50-2.82 AU). According to Nesvorný et al. (2015), there are at least 5 primitive families in that region, and for the present work we have focused on three of them: Padua, Nemesis, and Hoffmeister. As it can be seen in Fig. 1A, they overlap in the (a, i) orbital parameter space, and two of them overlap even in the (a, e) space. This might be indicative of a common origin and interestingly, the three families show a similar age. They also overlap in the (a, H) space (Fig. 1B), which make them an ideal case to see if we can discriminate between members from each family using spectroscopy. According to the taxonomical classification of their largest member using visible spectra, Hoffmeister is classified as a CF type family (neutral to blue spectral slope), Nemesis is a C-type family (neutral slope), and Padua is an X-type (redder slope). The distribution of WISE albedos (Mainzer et al. 2011) of Hoffmeister is rather different from what is seen on Nemesis and Padua (Fig. 1C), also indicative of different composition. Only spectra will help to compositionally characterize these families and to search for the presence of the 0.7 μm absorption band associated to hydration. This will allow us to compare the level of hydration in families from the inner to the outer belt (De Prá et al. 2017) and map the water inventory of the asteroid belt to constrain evolutionary models.

Figure 1: A) Distribution of the members of the three primitive collisional families in semimajor axis (a) vs. Eccentricity (top panel) and sine of inclination (bottom panel). The three families clearly overlap in the (a,i) space. B) Distribution of the three families in the absolute magnitude (H) - a space. There are clear overlapping regions where we can test if members of each family can be identified using spectra. C) Distribution of the albedos measured by WISE for the members of the three families.

In order to study these three families, we obtained visible spectra for a total of 124 asteroids (44 within the Nemesis and Hoffmeister families, and 36 within the Padua family) using the OSIRIS spectrograph at the 10.4m GTC, located at the Observatorio Del Roque de Los Muchachos (La Palma, Spain). In this work, we will present the first spectroscopic study of the Nemesis, Hoffmeister, and Padua families, and we will compare the results with those obtained for the families located in the inner main belt.

How to cite: Morate, D., de León, J., Licandro, J., de Prá, M., Pinilla-Alonso, N., Campins, H., and Cabrera-Lavers, A.: PRIMASS visits the primitive collisional families in the central asteroid belt:Nemesis, Hoffmeister, and Padua, Europlanet Science Congress 2021, online, 13–24 Sep 2021, EPSC2021-424, https://doi.org/10.5194/epsc2021-424, 2021.

The Javalambre Photometric Local Universe Survey (J-PLUS) is an observational campaign that aims to obtain photometry in 12 ultraviolet-visible filters (0.3–1 μm) of ∼8 500 deg2 of the sky observable from Javalambre (Teruel, Spain). Due to its characteristics and strategy of observation, this survey will let us analyze a great number of Solar System small bodies, with improved spectrophotometric resolution with respect to previous large-area photometric surveys in optical wavelengths.

The main goal of this work is to present here the first catalog of magnitudes and colors of minor bodies of the Solar System compiled using the first data release (DR1) of the J-PLUS observational campaign: the Moving Objects Observed from Javalambre (MOOJa) catalog.

Using the compiled photometric data we obtained very-low-resolution reflectance (photospectra) spectra of the asteroids. We first used a σ-clipping algorithm in order to remove outliers and clean the data. We then devised a method to select the optimal solar colors in the J-PLUS photometric system. These solar colors were computed using two different approaches: on one hand, we used different spectra of the Sun, convolved with the filter transmissions of the J-PLUS system, and on the other, we selected a group of solar-type stars in the J-PLUS DR1, according to their computed stellar parameters. Finally, we used the solar colors to obtain the reflectance spectra of the asteroids.

We present photometric data in the J-PLUS filters for a total of 3 122 minor bodies (3 666 before outlier removal), and we discuss the main issues of the data, as well as some guidelines to solve them.

How to cite: Morate, D., Marcio Carvano, J., Alvarez-Candal, A., De Prá, M., Licandro, J., Galarza, A., Mahlke, M., and Solano-Márquez, E.: J-PLUS: A first glimpse at spectrophotometry of asteroids – The MOOJa catalog, Europlanet Science Congress 2021, online, 13–24 Sep 2021, EPSC2021-425, https://doi.org/10.5194/epsc2021-425, 2021.

Introduction

The letter M (metal) to classify several asteroids was proposed for the first time by Zellner and Gradie [1] because of similarity of their polarimetric and spectral properties to iron meteorites. However, the possible meteorite analogues according to spectral data of these asteroids included not only iron meteorites but also some types of enstatite chondrites [2]. M-class was one of seven major classes in Tholen’s taxonomy well separated from other classes by featureless spectra and moderate surface albedo [3]. In the recent classifications based on spectral data alone [4,5] M-class is a part of X-complex which includes all asteroids with featureless spectra regardless of their albedo.

M-asteroids have caused a great interest to their study because it was believed that these asteroids could be the remnants of the metal cores of differentiated planetesimals. The largest M-type asteroid (16) Psyche has been selected as a target of the forthcoming NASA space mission. However, numerous observations of M-type asteroids by different techniques revealed that they can have diverse composition. In [6,7] the spectroscopic and radar observations were analyzed together to clarify the composition of M-type asteroids. According to their estimates, only about a third of M-type asteroids can be metal-dominated asteroids [6,7] although there is some inconsistency in compositional predictions between spectroscopic and radar observations [6].

Our goal is to consider polarimetric observations of M-type asteroids as complimentary technique to spectral and radar data and explore how polarimetry can improve our understanding of the nature and diversity of M-type asteroids. Here we present the results of new polarimetric observations of M-type asteroids and their analysis using all available data.

Observations

For observations we selected targets from the list of asteroids classified as M-type in [3] or X-complex asteroids in [4,5] with moderate surface albedo from 0.1 to 0.35. The main aim of our observations was the reliable determination of the values of polarimetric parameters characterizing the negative branch of polarization, i.e. the depth of polarization minimum Pmin and the inversion angle. Observations were started in 2020 and involved three telescopes: the 2.6-m telescope of the Crimean Astrophysical Observatory, the 2-m telescope of the Bulgarian National Astronomical Observatory in Rozhen and the remotely controlled Tohoku 60-cm telescope at Haleakala Observatory, Hawaii. Observations were made using CCD polarimeters in V or R filters at the 2-m and 2.6-m telescopes, and simultaneously in BVR filters at the 60-cm telescope. In total, polarimetric observations of 18 asteroids have been carried out from August 2020 to May 2021.

Results

We have analyzed the new observational data together with the available literature data on the polarimetry of M-type asteroids. The number of M-type asteroids for which it is possible to determine at least one of the polarimetric parameters (Pmin or the inversion angle) has increased to 45 objects. This is more than 70% of all main belt asteroids with diameters over 40 km that can be attributed to the M-type. The previous analysis by Gil-Hutton [8] included a data-sample of 26 M-type asteroids. We searched for possible relationships of polarimetric parameters with visible and infrared spectral slopes and broadband colors as well as infrared and radar albedos. We found that polarimetric parameters are diagnostic on asteroid’s composition and can be used to improve our current understanding of the composition of M-type asteroids based on spectral and radar data.

Conclusion

Polarimetric observations of M-type asteroids, analyzed together with their spectral and radar data, provide a better understanding of the composition and nature of M-type asteroids.

Acknowledgment

Ukrainian team is supported by the National Research Foundation of Ukraine (grant N 2020.02/0371 “Metallic asteroids: search for parent bodies of iron meteorites, sources of extraterrestrial resources”).

References

[1] Zellner, B., Gradie, J. Astron. J., 81, 262, 1976

[2] Chapman, C.R., Morrison, D., Zellner, B. Icarus, 25, 104,1975

[3] Tholen, D.J. In: Asteroids II (R. P. Binzel, T. Gehrels, and M. S. Matthews, Eds.), Univ. Arizona Press, p. 1139-1150, 1989

[4] Bus, S.J., Binzel, R.P. Icarus, 158, 146, 2002

[5] DeMeo, F.E., Binzel, R.P., Slivan, S.M., Bus, S.J. Icarus, 202, 160, 2009

[6] Neeley, J.R., Clark, B.E., Ockert-Bell, M.E., Shepard, M.K., Conklin, J., Cloutis, E.A., Fornasier, S., Bus, S.J. Icarus, 238, 37, 2014

[7] Shepard, M.K., Taylor, P.A., Nolan, M.C., et al. Icarus, 245, 38, 2015

[8] Gil-Hutton Gil-Hutton, R. Astron. Astroph., 464, 1127, 2007

How to cite: Belskaya, I., Berdyugin, A., Krugly, Y., Rumyantsev, V., Donchev, Z., Sergeyev, A., and Mykhailova, S.: What can the polarimetric properties of M-type asteroids tell us about their composition?, Europlanet Science Congress 2021, online, 13–24 Sep 2021, EPSC2021-359, https://doi.org/10.5194/epsc2021-359, 2021.

We present first results from a polarimetric survey of asteroids in the near-infrared J and H bands (1.25 and 1.65 microns, respectively). This survey has been enabled by the newly commissioned WIRC-Pol instrument on the Palomar 5 m telescope. WIRC-Pol simultaneously senses the four linear polarization components from the target, while using a half-wave plate to beam swap between them. This setup allows us to obtain bandpass polarimetric accuracies better than 0.1% for our targets. WIRC-Pol also obtains low resolution spectra of each Stokes component, allowing us to investigate the spectropolarimetric properties of our targets as a function of phase. We show polarimetric phase curves for objects that have been sampled at multiple phases, our initial spectropolarimetric findings, and discuss the results from modeling these observations.

How to cite: Masiero, J., Muinonen, K., Tinyanont, S., and Millar-Blanchaer, M.: Polarimetric properties of asteroids in the near-infrared, Europlanet Science Congress 2021, online, 13–24 Sep 2021, EPSC2021-47, https://doi.org/10.5194/epsc2021-47, 2021.

Organic materials are crucial for understanding the processes that took place at the early stages of Solar System formation and can bring some inputs on the origin of life on Earth. Organics is widely present in various groups of carbonaceous chondrite meteorites that are believed to be originated from dark primitive asteroids [1]. The absorption bands at 3.38, 3.42, and 3.47 µm are assigned to symmetric and asymmetric modes of CH3 and CH2 groups [2]. Thus, the identification of organic materials on the surface of low-albedo objects is rather difficult due to the fact that organic compounds have characteristic features outside the most accessible spectral region (0.4-2.5 µm). Furthermore, there is an overlap between organic and carbonate absorption bands [e.g., 3]. Up to now, the presence of organic band was detected only for a handful of objects, such as (1) Ceres [4], (24) Themis [5], (52) Europa [6], (65) Cybele [7], (121) Hermione [8], and (704) Interamnia [9]. The presence of organic features was also detected on the surface of the comet 67P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko [10].

In this work we studied the available spectra of low-albedo asteroids in order to find the signs of an absorption feature around 3.4 µm band and to examine the occurrence of organic matter on asteroid surfaces. We found 122 published spectra for 92 low-albedo asteroids which cover the range of 3-4 µm. Following spectra classification by [11], the majority of objects in the sample belong to the C-complex group. The rest of the objects belong to X-group, D-group, and T-group. We reduced our sample to 41 objects for which good-quality spectra were available. The presence of an absorption feature at 3.4 µm is detected for 20 asteroids (Fig. 1). As could be seen from the figure, the organic band is found for all asteroids in the sample that are larger than ~250 km, which is most probably related to a higher S/N ratio.

The band parameters such as central position and depth were calculated by fitting a 3.4 µm band with an Exponentially Modified Gaussian (EMG) following the method described in [12]. We found no correlation between the depth and position of the 3.4 µm band and the orbital elements of the asteroids.

Fig. 1. Diameter vs. S/N ratio in the 3.3-3.5 μm wavelength range for dark asteroids in our ample.

Spectral types are not distributed evenly among objects with and without a band around 3.4 µm: all the spectra, except (121) Hermione, not showing the 3.4 µm band belong to the Ch or Chg classes, whereas asteroids with a detected band mostly belong to C, B, and P types. However, only two Ch/Chg asteroids in the sample, (51) Nemausa and (78) Diana, have high S/N spectra. Thus, the absence of the organic band for Ch and Cgh type asteroids can be related to the generally lower S/N ratio and/or a shallower organic band for these groups. Furthermore, there is a tendency for asteroids with the 3.4 µm band to have redder J-K colors and more neutral U-V colors (Fig. 2, left). Additionally, there is a trend for asteroids with a detected 3.4 µm band to have lower albedo (Fig. 2, right).

Fig. 2. U-V vs. J-K colors (left) and U-V vs. albedo value taken from the AKARI survey (right). The largest asteroids in the sample (1) Ceres and (2) Pallas are not shown in the plots.

Acknowledgements. This project has received funding from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under grant agreement No 870403.

References

[1] Alexander, C., Fogel, M., Yabuta, H., Cody, G. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta, 71, 4380, 2007.

[2] Moroz, L. V., Arnold, G., Korochantsev, A. V., Wäsch, R. Icarus, 134,25, 1998.

[3] Alexander, C., Cody, G., Kebukawa, Y., et al. Meteoritics and Planetary Science, 49, 503, 2014.

[4] De Sanctis, M. C., Vinogradoff, V., Raponi, A., et al. MNRAS, 482, 2407, 2019.

[5] Rivkin, A. S., Emery, J. P. Nature, 464, 1322, 2010.

[6] Takir, D., Emery, J. P. Icarus, 219, 641, 2014.

[7] Licandro, J., Campins, H., Kelley, M., et al. A&A, 525, A34, 2011.

[8] Hargrove, K. D., Kelley, M. S., Campins, H., Licandro, J., Emery, J. Icarus, 221, 453, 2012.

[9] Usui, F., Hasegawa, S., Ootsubo, T., & Onaka, T. PASJ, 71, 1, 2019.

[10] Raponi, A., Ciarniello, M., Capaccioni, F., et al. Nature Astronomy, 4, 500, 2020.

[11] DeMeo, F. E., Binzel, R. P., Slivan, S. M., & Bus, S. J. Icarus, 202, 160, 2009.

[12] Potin, S., Manigand, S., Beck, P., Wolters, C., Schmitt, B. Icarus, 343, 113686, 2020.

How to cite: Hromakina, T., Barucci, M. A., Belskaya, I., Fornasier, S., Merlin, F., and Praet, A.: Investigation of the 3.4 µm absorption band in the spectra of low-albedo asteroids, Europlanet Science Congress 2021, online, 13–24 Sep 2021, EPSC2021-199, https://doi.org/10.5194/epsc2021-199, 2021.

The aim of the project is the classification of asteroids according to the most commonly used asteroid taxonomy (Bus-Demeo et al. 2009) with the use of various machine learning methods like Logistic Regression, Naive Bayes, Support Vector Machines, Gradient Boosting and Multilayer Perceptrons. Different parameter sets are used for classification in order to compare the quality of prediction with limited amount of data, namely the difference in performance between using the 0.45mu to 2.45mu spectral range and multiple spectral features, as well as performing the Prinicpal Component Analysis to reduce the dimensions of the spectral data.

This work has been supported by grant No. 2017/25/B/ST9/00740 from the National Science Centre, Poland.

How to cite: Klimczak, H., Kotłowski, W., Oszkiewicz, D., DeMeo, F., Kryszczyńska, A., Kwiatkowski, T., and Wilawer, E.: The impact of different parameter sets on the classification of asteroid types, Europlanet Science Congress 2021, online, 13–24 Sep 2021, EPSC2021-807, https://doi.org/10.5194/epsc2021-807, 2021.

Abstract

In this work, we present the experimental phase function and degree of linear polarization of two

sets of samples consisting of forsterite and spinel particles. The size distributions of the studied

samples span over a broad range in the scattering size parameter domain. This work is part of

an ongoing experimental project devoted to understand photopolarimetric observations of asteroids

and comets. In particular, we study the effect of the size on the scattering matrix elements, finding

a strong dependence of characteristic parameters, e.g. maximum of polarization and inversion angle,

on particles size.

Introduction

Polarimetric observations of dust clouds are a powerful tool in planetary science. They allow us

investigating the nature and properties of solar system bodies and planetary systems in different

stages of evolution, e.g. asteroids, comets, and protoplanetary disks. For example, they can be

used as a reference to refine the taxonomic classification of asteroids [1, 2] or they can help in the

discrimination of objects with cometary origin [3]. Some dust materials, like olivine and spinel,

are remarkably interesting for the investigation and characterization of solar system small bodies.

In particular, olivine is an extensively diffuse silicate mineral and spinel, a magnesium/aluminum

mineral, is a characteristic component of the unusual class of presumably ancient Barbarian asteroids

as well as an important component of Calcium Aluminium rich Inclusions (CAI) found in primitive

meteorites [6, 7]. Physical and optical properties of the dust, such as their refractive index, size,

composition, and structure define their ability to scatter the light. Therefore, in order to study these

materials, we need to experimentally characterize their photopolarimetric curves.

Measurements

We analyze six samples of olivine and spinel with different sizes. The samples denoted as Pebble

consist of millimeter-sized grains and lie in the geometrical optics regime. Further, two size

distributions consisting of particles smaller than 30 and 100 micrometers are produced out of the

olivine and spinel bulk samples. The measurements have been performed at the IAA Cosmic Dust

Laboratory (CODULAB), Granada, Spain [4]. The instrument allows to measure the scattering

matrix of a cloud of particles and can be set also to retrieve the scattering matrix of single mm-sized

particles [5]. The measurements have been obtained at 520 nm for the mm-sized grains and at 514

nm for the micron-sized samples. The scattering angle covers the range from 3° to 177°.

Results

Figures 1 and 2 show the phase function and degree of linear polarization (DLP) respectively of

olivine and of spinel samples.

The phase function curves show a strong dependence on particle size. We see that the micron-sized

samples have lower values with a rather flat trend at side- and back-scattering regions and a strong

increase in the forward direction. In contrast, the pebbles show u-shaped phase functions. The slope

of the phase function at side- and back-scattering regions is stronger in the case of the spinel.

The DLP curves also show a dependence on the size. They have the typical bell shape with a

negative branch at low phase angles. Spinel Pebble shows the higher maximum of polarization. The

three spinel samples show a well-defined negative polarization branch with an inversion angle located

around 28° regardless of the particle size. It is interesting to note in the case of the olivine samples

the inversion angle is highly dependent on particle size. The high inversion angle of Barbarian

asteroids polarization curves could be related to the presence of spinel in the form of millimeter

grains of regolith.

Figure 1: Phase function curves (left) and degree of linear polarization (right) for the three olivine

samples.

Figure 2: Phase function curves (left) and degree of linear polarization (right) for the three spinel

samples.

References

[1] Belskaya I.N. et al., Refining the asteroid taxonomy by polarimetric observations. ICARUS, Vol.

284, pp. 30-42, 2017.

[2] López-Sisterna C. et al., Polarimetric survey of main-belt asteroids. VII. New results for 82

main-belt objects. A&A, Vol. 626, A42, 2019.

[3] Cellino A. et al., Unusual polarimetric properties of (101955) Bennu: similarities with F-class

asteroids and cometary bodies. MNRAS, Vol.481, pp.L49-L53, 2018.

[4] Muñoz O. et al., Experimental determination of scattering matrices of dust particles at visible

wavelengths: The IAA light scattering apparatus. JQSRT, Vol. 111, 187 196, 2009.

[5] Muñoz O. et al., Experimental Phase Function and Degree of Linear Polarization Curves of

Millimeter sized Cosmic Dust Analogs ApJSS, Vol. 247, pp.19, 2020.

[6] Cellino A. et al., A successful search for hidden Barbarians in the Watsonia asteroid family.

MNRAS, Vol. 439, L75-L79, 2014.

[7] Devogéle M. et al., New polarimetric and spectroscopic evidence of anomalous enrichment in

spinel-bearing calcium-aluminium-rich inclusions among L-type asteroids. ICARUS, Vol. 304,

pp. 31-57. 2018.

How to cite: Frattin, E., Muñoz, O., Jardiel, T., Gómez Martín, J. C., Moreno, F., Peiteado, M., Tanga, P., Libourel, G., and Cellino, A.: Experimental phase function and degree of linear polarization of mm-sized and micron-sized olivine and spinel particles., Europlanet Science Congress 2021, online, 13–24 Sep 2021, EPSC2021-236, https://doi.org/10.5194/epsc2021-236, 2021.

Two asteroid sample return missions studied, in-situ, two primitive asteroid targets to unravel their physical and chemical properties as well as obtain regolith samples for return to Earth. We describe remote observations from OSIRIS-REx and Hayabusa2 to determine the hydration content of these primitive asteroid surfaces and implications for their aqueous alteration histories.

The NASA mission—Origins, Spectral Interpretation, Resource Identification, and Security–Regolith Explorer—OSIRIS-REx [1] studied the asteroid (101955) Bennu for two and a half years starting on its arrival at the asteroid on December 2018. The sample collection of surface regolith occurred on October 20th 2020 followed by the spacecraft departure from the asteroid on May 10th 2021 to begin its return cruise to deliver the sample to Earth in September 2023.

The JAXA mission Hayabusa2 [2] studied the asteroid (162173) Ryugu for a year and a half (June 2018 to November 2019), and the twice-collected regolith samples with the re-entry capsule landed on Earth on December 5th 2020. These samples are currently being analyzed in Earth laboratories.

Both missions had a near-infrared spectrometer onboard, amongst other instruments, which are the OVIRS spectrometer (OSIRIS-REx Visible and InfraRed Spectrometer) [3] and the NIRS3 spectrometer (Near-Infrared Spectrometer) [4].

The analysis of the asteroid surface reflectance spectra revealed the presence of an absorption band associated with OH/H2O centered near 2.74 microns [5] for asteroid Bennu and 2.72 microns for asteroid Ryugu [6]. This absorption band is caused by hydrated phyllosilicates across both asteroid surfaces. The absorption band, however, differs in center, shape and strength between the two asteroids with a weak and narrow band in the case of Ryugu and a wide asymmetric band for Bennu. This leads to the diagnoses of OH-bearing phyllosilicates on Ryugu [6] while H2O- and OH-bearing phyllosilicates on Bennu [5].

A similar absorption band has been observed in laboratory spectra of carbonaceous chondrite meteorites [7, 8]. Separately, the meteorite H content for many of these meteorites was measured by Alexander et al. [9, 10]. Correlations between spectral parameters computed on the hydrated phyllosilicate absorption band of clay minerals and their laboratory-measured water content was found by Milliken et al. [11, 12, 13] and absolute water estimation of Mars regolith was performed by [14].

As described in Praet et al. [15, 16], the normalized optical path length (NOPL) and effective single-scattering albedo (ESPAT) spectral parameters have been applied to estimate the hydrated phyllosilicates water and hydroxyl group hydrogen content (hereafter H content) of each asteroid global average surface. The estimation of the global mean H content of Bennu is 0.71 ± 0.28 wt.% and 0.52 −0.21+0.16 wt.% for Ryugu.

In the case of Bennu, the H content surface distribution shows a correlation with the geomorphology with higher values in the high latitudes and lower values in the equatorial band (between –20° and 20° latitudes). Whereas no such correlation is evident in the case of Ryugu as the NOPL and ESPAT parameter computed across its surface do not display any correlation with its surface geomorphological structures. These estimates and spatial trends will be updated as new information is derived from the returned samples (e.g., with enhanced thermal tail removal).

The estimated global H content value for Bennu is consistent with the H content range of aqueously altered meteorites such as heated CMs and C2 Tagish Lake, which is in agreement with [5, 16, 18]. As for Ryugu, its global H content is most similar to more strongly heated CMs, which is coherent with the best meteorite analogs for Ryugu near-infrared spectra (thermally metamorphosed CIs and shocked CMs) [6].

Our estimates of phyllosilicate water and hydroxyl group hydrogen content on Bennu and Ryugu, if confirmed by laboratory analysis on both returned samples, will allow the application of the same method to other asteroids, observed from the ground, and from space-telescopes. For asteroids with spectra exhibiting hydrated phyllosilicate absorption bands, such as the ones collected by the AKARI spectral survey [19] for example, estimation of their global mean H content will be possible.

The study of water and hydroxyl abundance on primitive asteroids is important for understanding the origin of terrestrial water and to constrain dynamical models and evolutionary processes to better understand the origin and evolution of our Solar System.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to the entire OSIRIS-REx Team for making the encounter with Bennu possible. This material is based upon work supported by NASA under Contract NNM10AA11C issued through the New Frontiers Program. We also thank the Hayabusa2 JAXA teams for their efforts in making the mission successful. AP and MAB acknowledge funding support from CNES.

References

[1] Lauretta D. S. et al. (2017) Space Sci. Rev., 212, 925-984.

[2] Tsuda ,Y., Yoshikawa, M., Abe, M., Minamino, H., Nakazawa, S. (2013) Acta Astronaut., 91, 356–362.

[3] Reuter, D.C. et al. (2018) Space Sci. Rev., 214, 54.

[4] Iwata, T., Kitazato, K., Abe, M., et al. (2017), Space Science Reviews, 208, 317.

[5] Hamilton, V.E. et al. (2019) Nature Astron., 3, 332.

[6] Kitazato, K. et al. (2019) Science, DOI: 10.1126/science.aav7432.

[7] Takir, D. et al. (2013) Meteorit. Planet. Sci., 48, 1618–1637.

[8] Takir, D. et al. (2019) Icarus, 333, 243–251.

[9] Alexander, C.M.O’D. et al. (2012) Science, 337, 721- 723.

[10] Alexander, C.M.O’D. et al. (2013) Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta, 123, 244-260.

[11] Milliken, R.E., Mustard J.F. (2005) JGR, 110, E12001.

[12] Milliken, R.E., Mustard, J.F. (2007a) Icarus,189(2), 574-588.

[13] Milliken, R.E., Mustard, J.F. (2007b) Icarus, 189, 550–573.

[14] Milliken, R.E., et al. (2007). J. Geophys. Res. 112, E08S07, doi: 10.1029/2006JE002853.

[15] Praet, A. et al. (2021a) Icarus, 363, 114427, doi: 10.1016/j.icarus.2021.114427.

[16] Praet, A. et al. (2021b) Astron. Astrophys. doi: 10.1051/0004-6361/202140900.

[17] Hamilton, V.E. et al., (2021) Astron. Astrophys. doi: 10.1051/0004-6361/202039728.

[18] Hanna, R.D. et al. (2020) Icarus, 346, 113760.

[19] Usui, F., Hasegawa, S., Ootsubo, T., Onaka, T. (2019). Publ. Astr. Soc. Japan 71.

How to cite: Praet, A., Barucci, M. A., Clark, B. E., Kaplan, H., Simon, A., Hamilton, V., Kitazato, K., and Matsuoka, M.: Comparison of the mean surface hydrogen content estimation of the asteroids (101955) Bennu and (162173) Ryugu and perspective for other asteroids., Europlanet Science Congress 2021, online, 13–24 Sep 2021, EPSC2021-288, https://doi.org/10.5194/epsc2021-288, 2021.

Asteroids with an average heliocentric distance of 1 au present special challenges to surveys. Because of the very slow Earth-relative net motion from one orbital revolution to the next, they can remain far from our planet and close to the Sun's location in the sky (Fig 1). For this reason, the likelihood of discovering objects for this type should be generally lower than for other near-Earth asteroids (NEAs). Observational incompleteness for these Earth coorbitals was quantified by Tricarico (2017) and is now readily apparent in the NEA inventory as a deficit of asteroids with a semimajor axis of 1 au (Fig 2).

Figure 1: Illustration of Earth-relative motion of an asteroid with a = 1.001 au and initially 180o away in orbital mean longitude. The asteroid is initially located behind the sun as seen from Earth and drifts towards the Earth’s location at a rate of 0.5o/year. After 180 yr, solar elongation has increased from 0 to 45o.

Figure 2: Number of NEAs in the NEODYS database (https://newton.spacedys.com/neodys/) on 16 May 2021 as a function of semimajor axis counted with a bin size of 0.02 au. Only asteroids with 1-sigma semimajor axis uncertainty of 0.001 au or better were included. The error bars correspond to Poisson counting statistics for each bin. Note the lack of asteroids with a semimajor axis of 1 au.

We have constructed a simple survey simulator to understand how this bias behaves for different asteroid orbits. The relative longitude λ - λEarth between the Earth and the asteroid is a key parameter determining whether an asteroid is discovered or not, affecting even bright asteroids that should otherwise be easy to discover even far from the Earth. Figure 3 shows the observational completeness for H=14 (D=4 km for pv=0.25) asteroids on a 40-yr synthetic survey down to a limiting magnitude of V=20.7 and a solar elongation cutoff of 70o. At a=1 au - the exact co-orbital condition - the asteroid is stationary as seen from the Earth and completeness is determined solely by the fraction of the orbit that resides within the solar elongation limit. Orbits away from 1 au gradually drift away from the anti-solar point and eventually exit the ``blind spot’’ caused by the solar elongation limit, allowing their detection. An important implication is that the gap in Fig 2 could contain undiscovered km-sized or larger asteroids which may be potentially hazardous (PHAs). To eliminate or significantly reduce the gap in a few decades or sooner, it would be necessary either to operate a survey with a much reduced solar elongation limit or move the detector away from the Earth.

Figure 3: Observational completeness for asteroids with semimajor axis within 0.01 au of Earth’s for a synthetic 40-year survey with a solar elongation cutoff of 70o and a limiting magnitude V=20.7. The asteroid parameters were H=14, e=0.1 and I=5o. Completeness takes values from 0 to 1 and is linearly proportional to greyscale intensity. The region of near-zero completeness centred at a = 1.000 au and Δλ = 180o is caused by the asteroid not exceeding the elongation cutoff for the duration of the survey.

At the meeting we will show model results to demonstrate how the observational completeness for co-orbital asteroids depends on the elements of the orbit: eccentricity, inclination, periapsis and node. An estimate for the number of as-yet-undiscovered co-orbital asteroids as a function of size will also be provided. In addition, we will be applying the simulator to known asteroids presently observed in different libration modes of the 1:1 resonance: Trojans (2010 TK7; Connors et al, 2011), horseshoes (419624 2010 SO16; Christou & Asher, 2011) and quasi-satellites (469219 Kamoʻoalewa; Chodas, 2016) and aim to report the results at the conference.

Acknowledgements: This work was supported via grant ST/R000573/1 from the UK Science and Technology Facilities Council (STFC).

References:

Chodas, P., 2016, The orbit and future motion of Earth quasi-satellite 2016 HO3, DPS meeting #48, id.311.04.

Christou, A. A., Asher, D. J., 2011, A long-lived horseshoe companion to the Earth, MNRAS, 414, 2965-2969.

Connors, M., Wiegert, P., Veillet, Ch., 2011, Earth’s Trojan asteroid, Nature, 475, 481-483.

Tricarico, P., 2017, The near-Earth asteroid population from two decades of observations, Icarus, 284, 416-423.

How to cite: Christou, A., Nedelchev, B., Borisov, G., Dell’Oro, A., and Cellino, A.: Earth's blind spot: A closer look at observational biases for Earth coorbital asteroids, Europlanet Science Congress 2021, online, 13–24 Sep 2021, EPSC2021-92, https://doi.org/10.5194/epsc2021-92, 2021.

The knowledge of even some basic physical properties of a NEO such as the composition and the internal structure has strong implications for both science and impact mitigation. Depending on its composition and internal structure a meter-size object can completely burn in the atmosphere or reach the ground excavating an impact crater. To date, only 20% of the known NEO population has been characterized. The percentage rises 30% when considering only objects larger than 1 km. The reason is that physical characterization requires availability of large aperture telescopes, accurate ephemerides, and can be performed only if the object is sufficiently bright.

International efforts devoted to NEO physical characterization have undoubtedly succeeded in the last decade in addressing this problem through the organization of extensive observational campaigns within the framework of international cooperative programs. Yet the observational work and the associated modelling and simulation research is far from being exhausted in particular as far as the physical characterization of PHOs and smaller objects (D<140 m) passing close or colliding with the Earth are concerned.

The aim of the NEOROCKS project is to look at the 2020 horizon and beyond, by proposing an innovative approach that takes into consideration the incoming operations of the next generation sky surveys (with wide-field high-sensitivity telescopes), which will dramatically change the NEO discovery scenario.

The Project

NEOROCKS utilizes an innovative approach focused on:

- a) performing high-quality physical observations and related data reduction processes;

- b) investigating the strong relationship between the orbit determination of newly discovered objects and the quick execution of follow-up observations in order to face the threat posed by the “imminent impactors”;

- c) profiting of the European industrial expertise in on-going Space Situational Awareness initiatives to plan and execute breakthrough experiments foreseeing the remote tasking of highly automatized robotic telescopes, in order to provide a proof-of-concept rapid-response system;

- d) guarantee extremely high standards in the data dissemination through the involvement at agency level of a data center facility already operating in a European and international context.

The key issue, which marks the radical difference of this approach, is the early onset (from discovery) of a direct link between orbital and physical characterization. Our process continuously analyses the new published detections, in order to find out those which deserve attention as potentially hazardous. For each object identified, the astrometric follow-up and the associated orbit improvements are activated in closed loop until the accuracy of the ephemerides enables successful attempts of observations devoted to physical characterization. Speeding up this process, to complete it within the typical period of visibility of a newly discovered object in the vicinity of our planet (days to weeks), provides an innovative pre-operational scenario for addressing the “imminent impactors” threat. This is particularly relevant since small objects in route of collision with the Earth are likely to be routinely discovered by the new generation NEO sky surveys. Therefore, our approach aims to introduce an entirely new methodology into future operational NEO hazard monitoring systems.

The introduction of novel methods for orbit determination and for the prioritization of follow-up observations are at the core of our approach. To assess performances that it can reach, a real-time telescope tasking experiment is envisaged as a test case scenario with the potential to scale up to a global level.

Observation campaigns focussed on already known objects and the associated data reduction and analysis are also performed throughout the project, in order to provide high-quality data on specific interesting targets for science and mitigation. This goal is achieved thanks to the participation of astronomical institutions and observatories that can access top-class instrumentation (e.g. 3-10m aperture telescopes) and to perform challenging radar observations within the framework of international collaborations.

NEOROCKS also sets up necessary infrastructure to store, maintain and disseminate data produced and tools developed, well beyond the nominal lifetime of the project, thus granting the continuation of its approach and the update of its results. This is achieved through partnership with ASI Space Science Data Centre (SSDC https://www.ssdc.asi.it/), which is equipped with necessary HW/SW environment.

Team and activities

The main subject of NEOROCKS is to boost the NEO follow-up observations scenario devoted to determine the parameters characterizing asteroid properties, such as composition, shape, spin and mass: these quantities are relevant for our understanding of the nature of NEOs and the potential hazard they pose to human beings.

Another fundamental activity is focused in orbit determination and data management: special attention will be given to the timely detection and characterization of small potential imminent impactors of the Earth, which are likely to represent the next real threat.

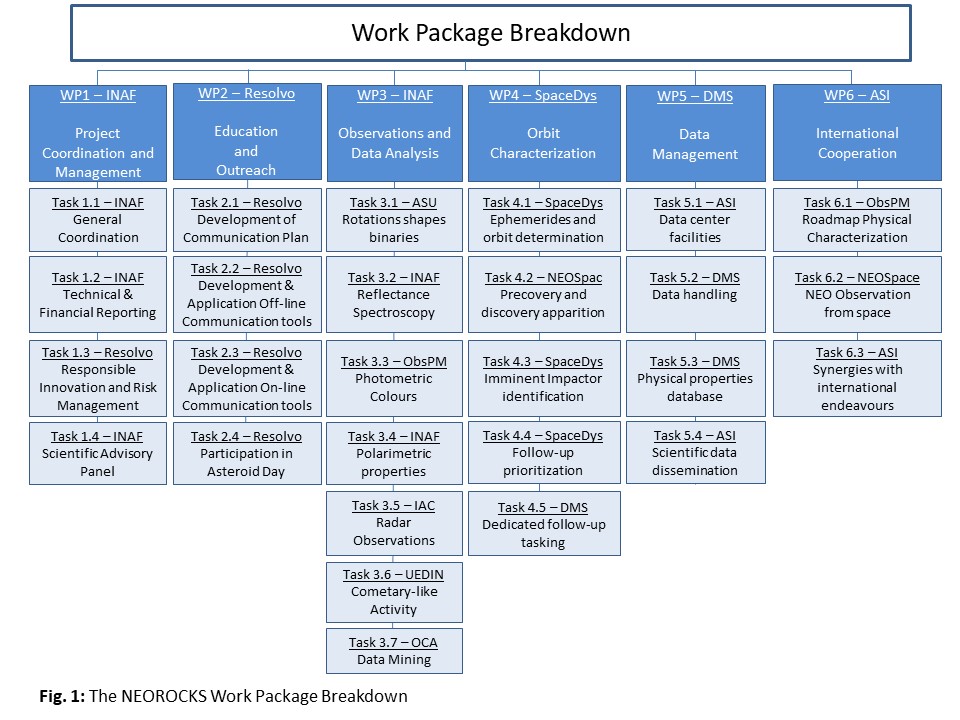

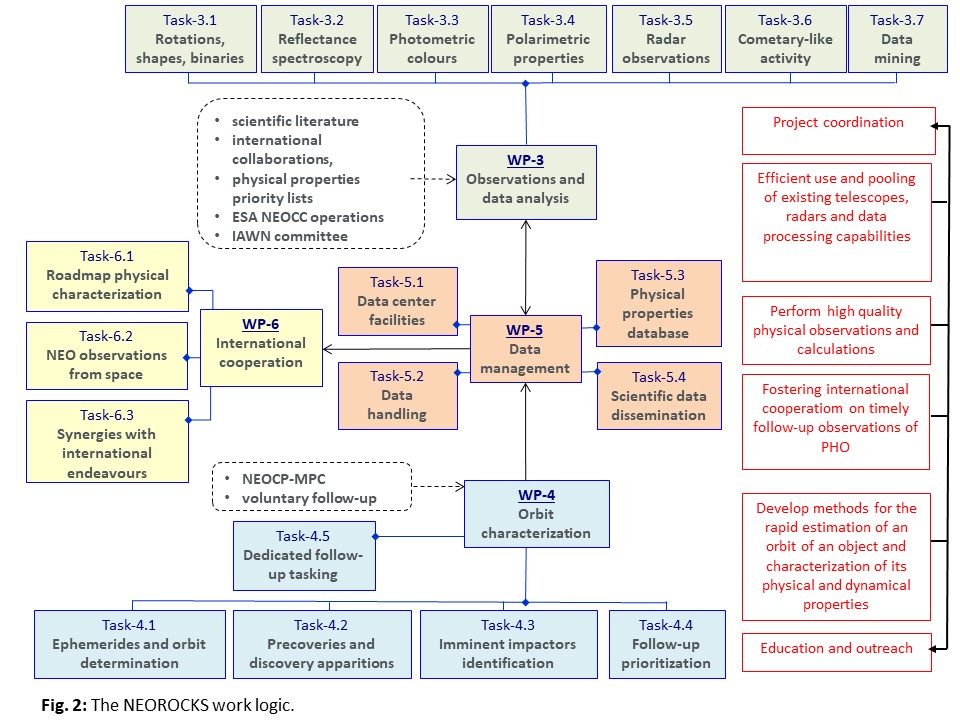

Fig. 1 shows the Work Package Breakdown and Fig. 2 the Work Logic.

NEOROCKS has the potential to perpetuate the approach followed during the project and the results obtained, through the in-kind contribution of the ASI-SSDC in hosting the project products. The possibility of profiting from a well-established facility devoted to science data exploitation after the project is finished ensures a high-level dissemination toward the scientific and technological communities involved in NEO research as well as to the public at large.

The NEOROCKS team includes also industrial partnerships actively participating to European Space Awareness programmes. The goal of this activity is to probe the engagement of European and international partners in a proactive contribution to the detection of NEO potential threats, as well as to the planning and implementation of effective mitigation measures in a highly synergic and complementary scenario.

Acknowledgements. This project has received funding from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under grant agreement No 870403.

How to cite: Dotto, E., Banaszkiewicz, M., Banchi, S., Barucci, M. A., Bernardi, F., Birlan, M., Carry, B., Cellino, A., De Léon, J., Lazzarin, M., Mazzotta Epifani, E., Mediavilla, A., Nomen Torres, J., Perna, D., Perozzi, E., Pravec, P., Snodgrass, C., and Teodorescu, C. and the NEOROCKS team: The EU Project NEOROCKS — NEO Rapid Observation, Characterization, and Key Simulations Project, Europlanet Science Congress 2021, online, 13–24 Sep 2021, EPSC2021-389, https://doi.org/10.5194/epsc2021-389, 2021.

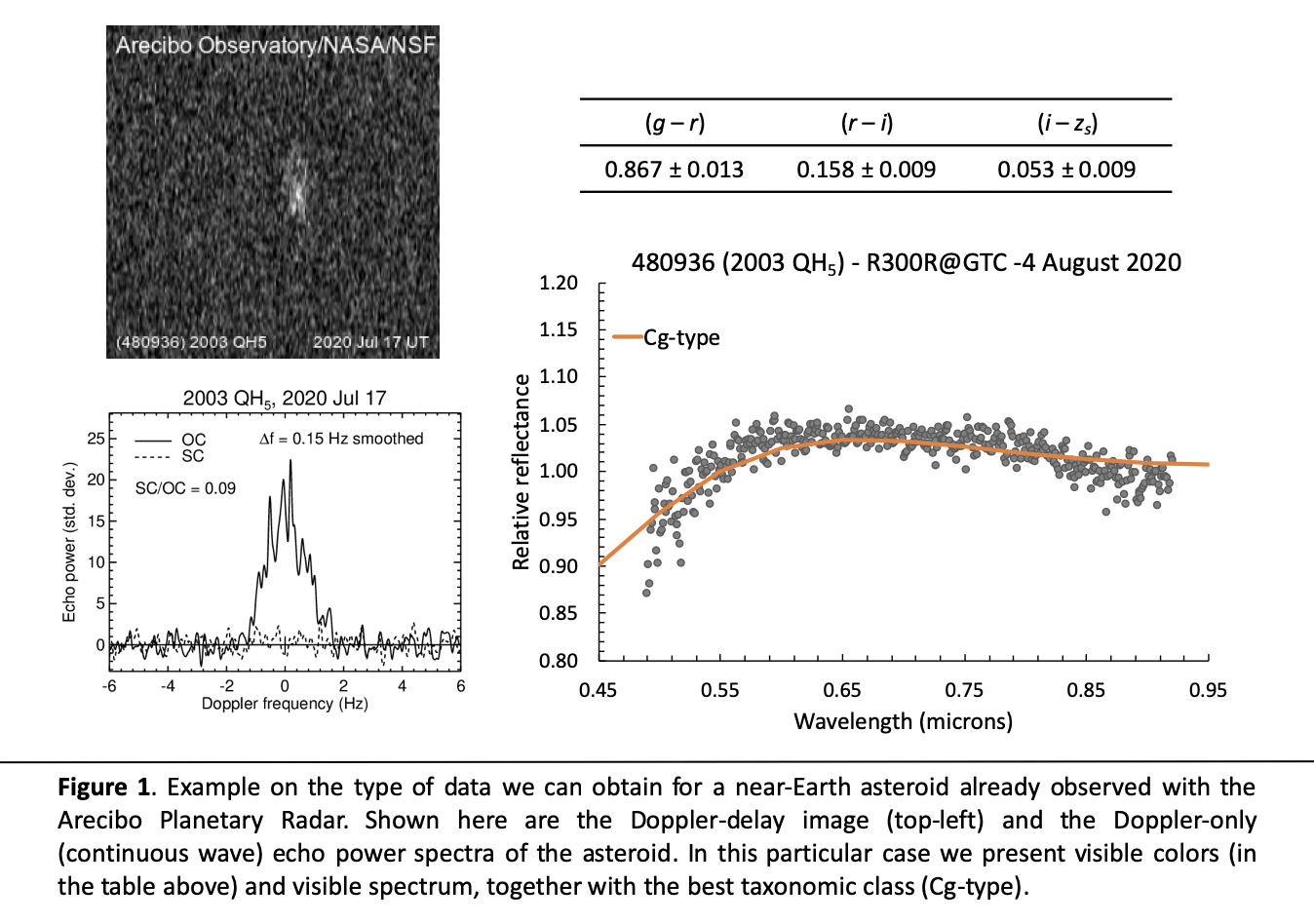

Introduction. The NEO Rapid Observation, Characterization and Key Simulations (NEOROCKS) project is funded (2020-2022) through the H2020 European Commission programme to improve our knowledge on near-Earth objects by connecting expertise in performing small body astronomical observations and the related modelling needed to derive their dynamical and physical properties. The Instituto de Astrofísica de Canarias (IAC), and in particular members of the Solar System Group, participate in the NEOROCKS project and currently lead one specific task: to collect observational data, mainly in the visible and near-infrared wavelength regions, of NEAs that have been observed in the past using the Arecibo Planetary Radar. In this work we present preliminary results, focusing on those targets having high signal-to-noise ratio radar data.

Observations. Our observations include spectroscopy, color photometry and lightcurves. They are performed using the facilities located at the Observatorios de Canarias (OOCC), that include the El Teide Observatory in the island of Tenerife and the El Roque de los Muchachos Observatory in the island of La Palma. Visible and near-infrared spectra are mainly obtained using the 10.4-m Gran Telescopio de Canarias (GTC) and its visible (OSIRIS) and near-infrared (EMIR) spectrographs. We also use the ALFOSC spectrograph at the 2.5-m Nordic Optical Telescope (NOT). Visible color photometry is obtained using the MuSCAT2 instrument at the 1.5-m Telescopio Carlos Sánchez (TCS). The setup allows to obtain simultaneous imaging in the g, r, i, and zsvisible bands. Time-series photometry in the visible is obtained using several telescopes, including the 46-cm TAR2, 80-cm IAC-80, and 1-m Jacobus Kapteyn Telescope (JKT).

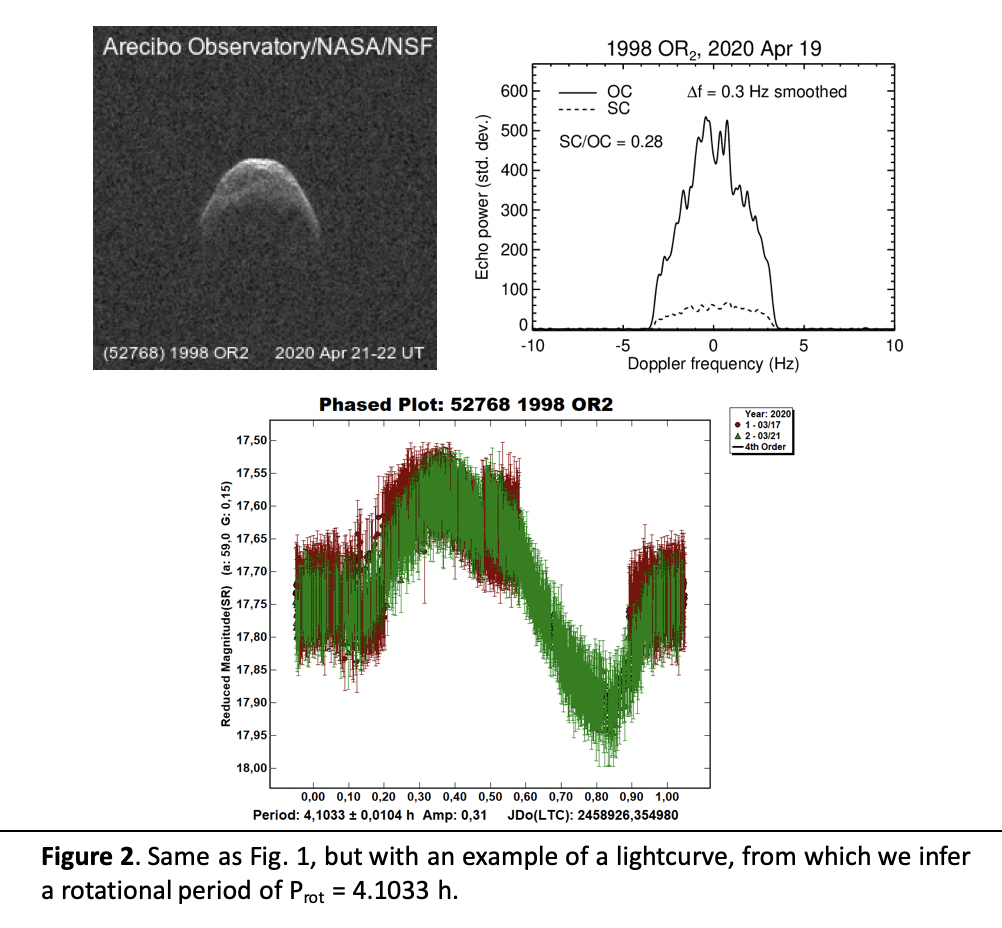

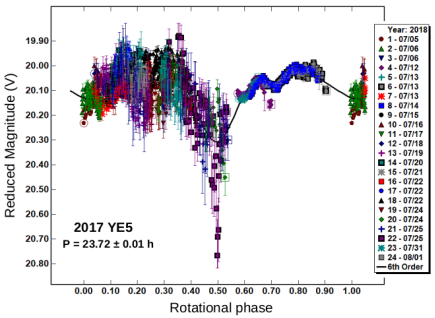

Results. Spectra in the visible and/or the near-infrared wavelengths, as well as color photometry in the visible, are used to taxonomically classify the targets and to infer their composition (Fig 1). In the case of having no albedo measurements for one object, we can also use the taxonomy to have an estimation of the albedo based on the spectral class, and therefore determine the size of the asteroid. Lightcurves are used to both get the asteroid rotational period and, together with radar data, to obtain the shape and the spin axis orientation of the target (Fig. 2). In this way, a full characterization can be obtained for every asteroid observed within this program.

Acknowledgements. This project has received funding from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under grant agreement No 870403.

How to cite: de León, J., Licandro, J., Popescu, M., Medeiros, H., Morate, D., Pinilla-Alonso, N., Perez-Toledo, F., and Planetary Radar Team*, A. and the NEOROCKS Team: NEOROCKS characterization programme of near-Earth asteroids previously observed with radar, Europlanet Science Congress 2021, online, 13–24 Sep 2021, EPSC2021-221, https://doi.org/10.5194/epsc2021-221, 2021.

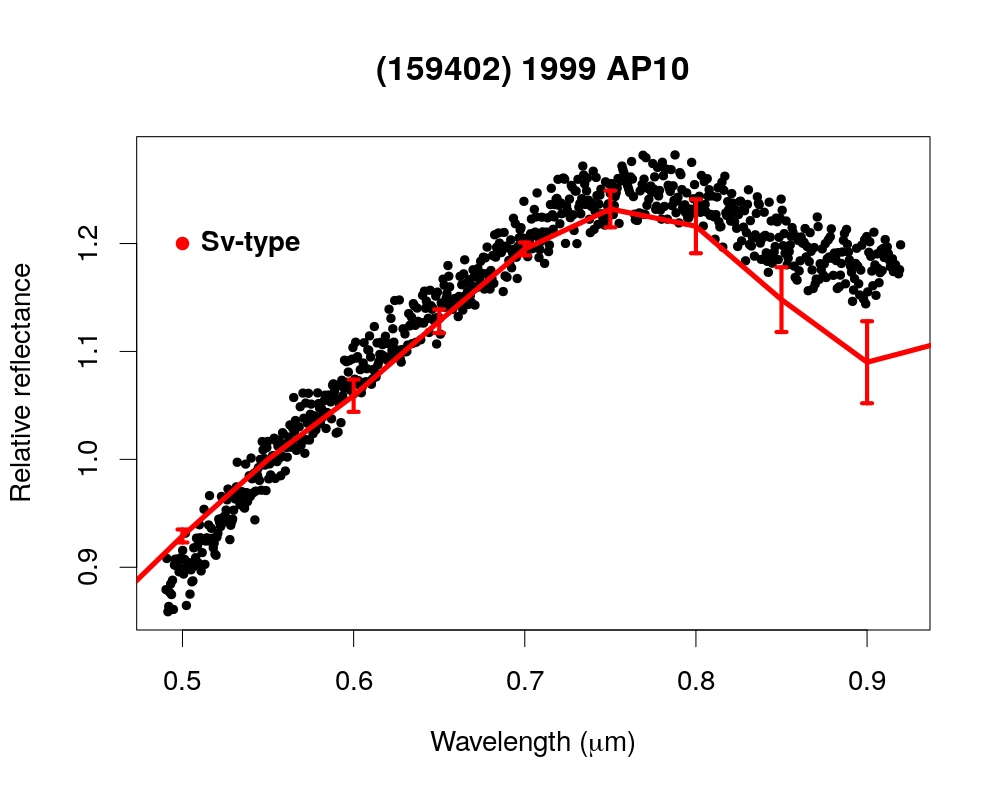

Introduction. The near-Earth object (NEO) population is composed of asteroids and comets that have orbits close to the Earth. This population is the most accesible vestige from the building blocks that formed the Solar System, for spacecrafts, and for detailed observations from ground-based facilities. The proximity of these objects give us advantages, but also risks. The NEO Rapid Observation, Characterization and Key Simulations (NEOROCKS) project has been recently funded (2020-2022) through the H2020 European Commission programme to improve the knowledge on NEOs by connecting expertise in performing small body astronomical observations and the related modelling needed to derive their dynamical and physical properties. The IAC, and in particular members of the Solar System Group, participate in the NEOROCKS project and are currently leading one specific task to do observations of NEOs in support of the Arecibo Planetary Radar Program, using the facilities located at the Observatorios de Canarias (OOCC) and managed by IAC. These observations include times-series photometry (light curves), visible to near-infrared spectroscopy, and color photometry. We are focusing in those targets observed in the past by the Arecibo telescope and which have high signal-to-noise (SNR) radar data. In this work we present the results obtained for asteroid (159402) 1999 AP10.

Observations. Our observations included spectroscopy and time-series photometry – over the visible wavelength. Spectroscopic data were obtained with the ALFOSC spectrograph at the 2.5-m Nordical Optical Telescope (NOT), located at the El Roque de Los Muchachos Observatory (La Palma). A solar analogue star was observed at the same airmass as that of the asteroid. Data reduction followed standard procedures and was done using IRAF tasks. The spectra were bias and flat-field corrected before extracted and collapsed to one dimension. We wavelength calibrated both the spectra of the asteroid and solar analogue using ThAr+Ne+He lamps. In a final step, we divided the spectrum of the asteroid by the spectrum of the solar analogue to obtain the asteroid reflectance. In the attempt to obtain the rotational properties as rotational period, spin direction and shape model for the asteroid (159402) 1999 AP10, we did light curve observations between 2020 and 2021 using the TAR2 at TAR (Remote Open Telescope, Telescopio Abierto Remoto) installation. This telescope is a robotic observatory with two 42 cm diameter Centurion telescopes (TAR1 and TAR2), equipped with high-sensitivity FLI-Kepler sCMOS cameras and located at Teide Observatory (Tenerife). The observations at TAR2 were performed using the clear filter. To process the photometric images and to obtain the magnitudes we used the Photometry Pipeline (PP) developed by Mommert (2017). We used the software MPO Canopus to obtain the rotational period from the light curves. For the determination of the photometric shape model, we used the programs described by the model from Kaasalainen and Torppa (2001) and Kaasalainen et al., (2001).

Results. In Fig. 1, we present the spectrum over the visible wavelengths of the asteroid (159402) 1999 AP10, it is normalized to unity at 0.55 μm (black points). We used the M4AST Tool (Popescu et al. 2012; http://spectre.imcce.fr/m4ast/index.php/index/home) to obtain a taxonomical classification of this object, finding that it best fits into the S-complex (DeMeo et al. 2009), i.e., it is composed mainly of silicates.

Figure 1: The spectrum of (159402) 1999 AP10 (black points). The spectral curve is normalized to unity at 0.55 μm. Using the M4AST we have the curve of the best fit in red lines from taxonomic classification of Sv-type.

Time-series photometry is a very efficient technique to obtain asteroid physical properties like rotation period, spin orientation, size, and shape. In the JPL webpage (https://ssd.jpl.nasa.gov/sbdb.cgi) the rotational period for the asteroid (159402) 1999 AP10 is 7.908 h. Using our light curves (with MPO Canopus), we obtain a rotational period of 7.9176 +/- 0.0152 h, and a light curve amplitude of 0.28 mag. The Fig.2 shows the light curves used to find the best fit and the rotational period. The obtained value for the period is in good agreement with the one listed at JPL.

Figure 2: Three light curves of the asteroid (159402) 1999 AP10 from January, 2021. We did the fit on MPO Canopus and we obtained the rotational period of 7.917 +/- 0.0152 h and a light curve amplitude of 0.28.

By obtaining rotational data from an asteroid at different viewing geometries allows to determine its photometric shape model (Kaasalainen and Torppa 2001; Kaasalainen et al. 2001). We observed the asteroid (159402) 1999 AP10 at several viewing geometries. Thus, we will present two preliminary photometric shape models, the first with only the data obtained by us and the second with our data plus data from the Asteroid Lightcurve Photometry Database.

References.

Mommert, M. PHOTOMETRYPIPELINE: An Automated Pipeline for Calibrated Photometry, Astronomy & Computing, 18, 47, 2017.

Kaasalainen, M., Torppa, J., Optimization Methods for Asteroid Lightcurve Inversion. I. Shape Determination, Icarus, 153, 24-36, 2001.

Kaasalainen, M., Torppa, J., Muinonen, K., Optimization Methods for Asteroid Lightcurve Inversion. II. The Complete Inverse Problem, Icarus, 153, 37-51, 2001.

Popescu, M., Biirlan M., Nedelcu D. A., Modeling of asteroid spectra - M4AST, Astronomy & Astrophysics, Volume 544, id.A130, 10 pp, 2012.

DeMeo, F. E., Binzel R. P., Silvan, S. M., Bus, S.J., An extension of the Bus asteroid taxonomy into the near-infrared, Icarus, 202, 160-180, 2009.

Acknowledgements. This project has received funding from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under grant agreement No 870403.

How to cite: Medeiros, H., de León, J., Licandro, J., Popescu, M., and Pinilla-Alonso, N. and the Arecibo Planetary Radar Team* and NEOROCKS Team**: Physical characterization of near-Earth asteroid (159402) 1999 AP10 in support of the Arecibo Planetary Radar Program within the NEOROCKS project., Europlanet Science Congress 2021, online, 13–24 Sep 2021, EPSC2021-783, https://doi.org/10.5194/epsc2021-783, 2021.

- Introduction

The study of near-Earth objects (NEOs) is crucial to better understand the origin, formation and the evolution of the solar system. In particular, compositional, morphological and orbital characterisation of NEOs sheds light on the delivery of water and organics [1,2,3] to the prebiotic Earth, while ironically, some NEOs could be potential hazards for life on Earth [4], as it has been witnessed in the past during impacts. Furthermore, these objects are also of interest for the future of humankind, for they could be useful as vital resources during interplanetary travel. Given this context, we apply the G-mode multivariate statistical clustering method [5,6,7] on the orbital parameters of the currently available NEOs population, to probe potential associations with their spectral classification [8,9,10].

- Data and methods

We apply the G-Mode multivariate statistical clustering analysis to selected orbital elements of NEOs to determine any dynamical clustering of objects. Once the clusters of objects are found, we proceed to investigate whether they have any correlations with spectral classes. The G-mode method leads to an automatic statistical clustering of a sample containing N objects (NEOs in this case), described by M variables (orbital elements) with the only control imposed by the user being the confidence level q1, expressed in terms of σ.

Our sample consists of 10669 NEOs belonging to the dynamical groups Atiras, Atens, Apollos and Amors, available from the Minor Planet Center, filtered based on their orbital uncertainty (excluding those with an uncertainty parameter > 4). Our input parameters to the G-mode method are twofold. First, we use three variables: inclination (i), eccentricity (e) and semi-major axis (a) of the orbit as these are the main three parameters that define an orbit around the Sun. Secondly, we include three pseudo-parameters: mean orbital intersection distance with respect to the Earth (eMOID), perihelion distance (q) and aphelion distance (Q) of the orbit, in addition to the aforementioned three parameters, thus using six variables.

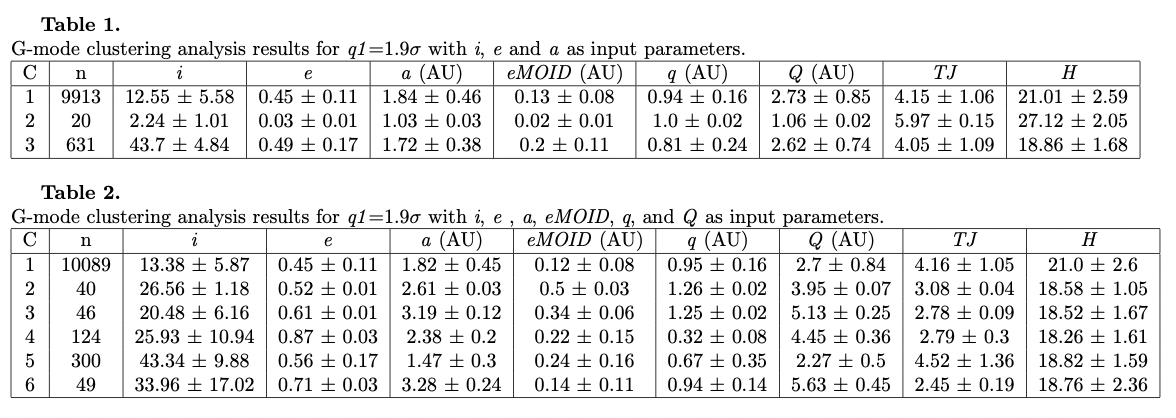

- Preliminary results

Using i, e and a of the NEOs in our sample as inputs for G-mode, we obtain three clusters of NEOs at q1=1.9σ (with an accurate classification probability of 94.26%). The mean parameter values of each cluster with the median absolute deviation are given in Table 1. We have also reported some other parameters of interest, which include, Tisserand parameter with respect to Jupiter (TJ) and the absolute magnitude H. At this criterion, the vast majority of objects are clustered in the cluster #1. The cluster #2 with only 20 objects, appears interesting, as it is constrained by low-inclined, quasi-circular Earth-like orbits. The objects of the final cluster #3 are constrained by their relatively larger inclinations.

We next used six variables: i, e, a, eMOID, q and Q as inputs for G-mode, while still holding q1 fixed at 1.9σ, in which case six clusters are found as reported in Table 2. Among the reported clusters, clusters #3,4 and 6 are of particular interest, for they could be associated with Jupiter-family cometary nuclei (2 < TJ < 3) as per their Tisserand parameter with respect to Jupiter. As such, the objects in these three clusters could potentially be extinct cometary nuclei. Interestingly, these clusters also have relatively higher eccentricities. We have checked available taxonomic classifications of NEOs [11,12,13] in the literature to get an insight into the composition of the objects found in our G-Mode clusters. Although taxonomic classifications are not available for the majority of members in the clusters, we find that (i) cluster #3 contains 4 C-type objects, (ii) cluster #4 contains 1 C-type, 2 D-type, 1 L-type, 5 S-type and 1 X-type objects, (iii) cluster #5 contains 1 B-type, 1 C-type, 1 T-type and 1 X-type objects. Apart from the S-type objects, the others usually have dark and red spectra indicative of primitive origin, which does not reject a cometary composition.

We will augment this on-going study with more data and final results will be presented and discussed.

- Acknowledgements

We acknowledge the financial support from Agenzia Spaziale Italiana (ASI, contract No. 2017-37-H.0 CUP F82F17000630005). We also acknowledge funding from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under grant agreement No. 870403.

References

[1] Marty, B., Guillaume, A. et al. 2016, Earth and Planetary Science Letters, Volume 441, Pages 91-102

[2] Altwegg, K, Balsiger, H, Bar-Nun, A. et al. 2015, Science, Vol. 347, Issue 6220, 1261952

[3] Ehrenfreund, P. & Sephton 2006, Faraday Discuss., The Royal Society of Chemistry, 133, 277-288

[4]Perna, D., Barucci M. A., Fulchignoni M. 2013, Astronomy and Astrophysics Review, Vol. 21,65

[5] Barucci, M.A., Capria, M.T., Coradini, A. et al. 1987, Icarus 72, 304

[6] Gavrishin, A. I., et al. 1992, Earth, Moon and Planets, 59, 141-152

[7] Barucci, M.A., Belskaya, I., Fulchignoni, M. et al. 2005, AJ 130, 1291

[8] Bus, S. J., & Binzel, R.P. 2002, Icarus 158, 146

[9] DeMeo, F. E., Binzel, R. P., Slivan, S. M. & Bus, S. J. 2009, Icarus, 202, 160-180

[10] DeMeo, F. E., Alexander, C. M. O., Walsh, K. J.et al. 2015, Asteroids IV, 13-41

[11] Perna, D., Barucci, M.A. et al. 2018, Planetary and Space Science, 157, 82-95

[12]Devogèle, M., Moskovitz, N. et al. 2019, The Astronomical Journal, American Astronomical Society, 158, 196

[13] Ieva, S., Dotto, E. et al. 2020, A&A, 644, A23

How to cite: Deshapriya, J. D. P., Perna, D., Bott, N., Hasselmann, P. H., Giunta, A., Dotto, E., Perozzi, E., Ieva, S., and Mazzotta Epifani, E.: Statistical clustering analysis of NEOs using their orbital parameters to find correlations with spectral classes, Europlanet Science Congress 2021, online, 13–24 Sep 2021, EPSC2021-614, https://doi.org/10.5194/epsc2021-614, 2021.

1.Introduction

In recent decades, we have been observing an exponential increase in near-Earth asteroids(NEAs) discoveries especially smaller than 200m(VSAs). According to the Holsapple model and observational data[2], VSAs can rotate much faster than larger asteroids. The reason for this is the monolithic structure as opposed to the larger asteroids made of smaller stones, the so-called rubble pile. VSA holds together mainly due to cohesive forces, not gravity, so many of them have rotational periods shorter than the 2.2h spin limit typical of rubble piles.

However, we do not know much about these objects, especially in terms of their taxonomy, which may turn out to be the key to a better understanding of the composition of VSAs, thereby their threats, and a better determination of the rotation limit taking into account the taxonomic type. Only ~1\% of these bodies are assigned a taxonomic class[7].

2.VSA observation issues and methods

VSAs are faint, with a mid-class telescope(<=2m), they can only be observed during close approaches, when they move quickly on the celestial sphere. This makes observations difficult using the classical methods used for further objects.

In our photometric observation, the telescope follows the asteroid keeping the NEA image circular on CCD frame, but the star images extend into long trails. An example of such observations at extremely high speed NEA on the sky was presented at the last year's EPSC(see[4]). Luckily, there was a photometric night then and instrumental measurements were enough to determine the rotation period. In worse conditions and/or when we want to determine the colour indices, we need accurate differential photometry. For this purpose, we use a circular aperture for the asteroid image and a pill aperture[1] for comparison stars images. We raised the issue of the use of the pill aperture in NEA photometry in[5]. Solar analogs from the PanSTARRS catalog were used as comparison stars.

An appropriate observation strategy is essential in determining the color indices of newly discovered NEAs. We need to know the rotation period. Many VSAs are superfast rotators(P<2.2h), and our observations of new objects are adapted to effectively detect periods between almost the entire range at relatively high S/N.

The general idea is to make 10s exposures for 15min (detection period ~1-15min) followed by 60s exposures for 2h (detection period ~5-120min) and, depending on the observation time, repeat these observation blocks several times. Exposures in these blocks are made with wideband filters.

Between these blocks we make a sequence of B,L,V,L,R blocks - each with 60s exposures taken for 15-20min, where L is our broadband filter.

Then, by moving the B,V,R lightcurves to the most accurate L lightcurve, one can determine the magnitude shift in relation to the L lightcurve, obtaining L-B,L-V,L-R, hence we get B-V and V-R.

We noticed that in the case of rotation periods close to the time of colour exposures, we can assume that each measurement is averaged brightness over the period. Then we determined the brightness in a given filter from the arithmetic mean, and the uncertainty from the standard deviation of the mean. The same can be done when the exposure time is a multiple of the period.

To check the impact of the assumption of ideal averaging over period on the results, we run simulations. We assume that the synthetic composite lightcurve obtained from 10-second exposures is the ideal curve. We integrate this synthetic composite lightcurve over the period to get the brightness we would get if the exposure time were equal to the period. Then we integrate the part of the curve corresponding to the color exposure time and repeat this by slightly shifting the phase from which we start to integrate, until we return to the initial phase. In this way, we get all possible values that we can get at a given exposure time. Then we compare the mean result with the value obtained by the integration over the period.

3.Observation and results

We conducted our observations in search of super-fast rotating VSAs between October 2020 and April 2021. We were able to determine the physical properties of several objects. Most of the observations were made with the 0.7-m RBT/PST2 telescope at the Winer Observatory in Arizona. For 2021 DW1, we organized a larger campaign involving telescopes from around the world. We devoted a separate poster to this object at this conference[6].

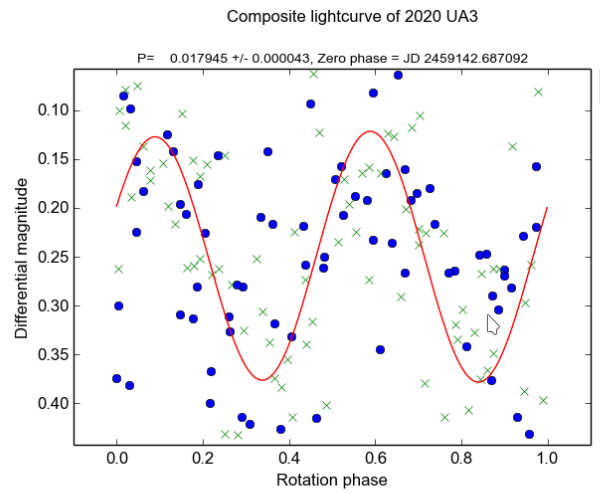

Below are the results for 2020 UA, which we observed on 20th October 2020. More details and results for the remaining asteroids will be announced at the conference.

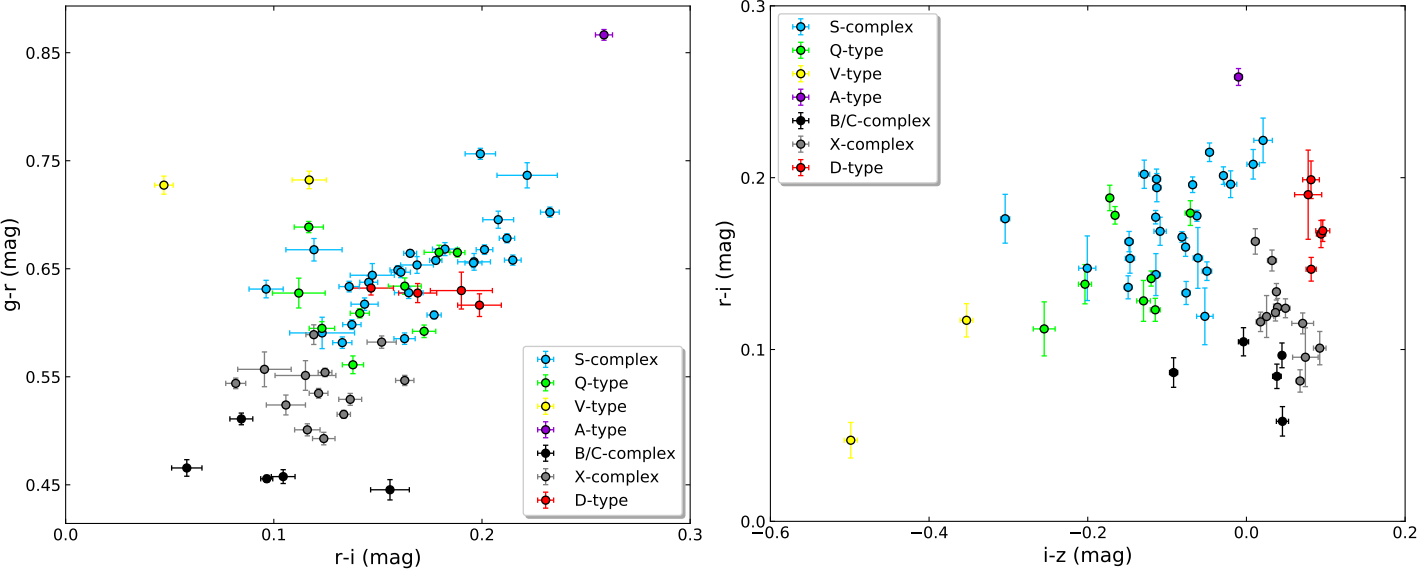

In Fig.1, we present the composite lightcurve for the best solution of the rotation period P=64.60+/-0.015s and amplitude 0.25mag. Since the time of colour exposures is 93% of the rotation period, we checked whether we can assume that P=texp for the determination of indices. It turned out that the impact was negligible, the average difference between the true average brightness period and our results is 0.0003+/-0.0047mag. The final indices are presented in Fig.2.

Fig.1.Composite lightcurve for 2020 UA. We used two 10-s exposure blocks during 15min each. The break between the blocks was 6.5h.

Fig.2.Colour-colour plot. The blue point is the result for 2020 UA(brightness in g,r,i obtained using PanSTARRS solar analogs), the uncertainty range is marked with a cross. Other symbols represent data for NEAs of various taxonomic types taken from[3].

References

[1]Fraser et al.(2016) AJ,151,151-158

[2]Holsapple(2007) Icarus,187,500-509

[3]Ivezic et al.(2001) AJ,122,2749-2784

[4]Koleńczuk et al. (2020) EPSC Abstracts,Vol.14,EPSC2020-809,https://doi.org/10.5194/epsc2020-809

[5]Koleńczuk, Proceedings of the Polish Astronomical Society,Vol.10,ISBN:978-83-950430-8-6,2020,101-104

[6]Kwiatkowski et al. Photometry and model of near-Earth asteroid 2021 DW1 from one apparition, EPSC 2021

[7]Perna et al.(2018) P&SS,157,82-95

How to cite: Koleńczuk, P. and Kwiatkowski, T.: Determination of colour indices of super-fast rotator near-Earth asteroids, Europlanet Science Congress 2021, online, 13–24 Sep 2021, EPSC2021-758, https://doi.org/10.5194/epsc2021-758, 2021.

The near-Earth asteroid (3200) Phaethon is classified as an active asteroid and is one of the largest objects with a perihelion within the orbit of Mercury. A dust tail has been observed during each of the last 3 closest approaches with the Sun. The activity, which is likely not driven by volatile sublimation, strongly suggests that Phaethon is the most likely parent body of the annual Geminid meteor shower. Phaethon is the main target for the JAXA DESTINY+ mission that will measure the dust environment, among other goals.

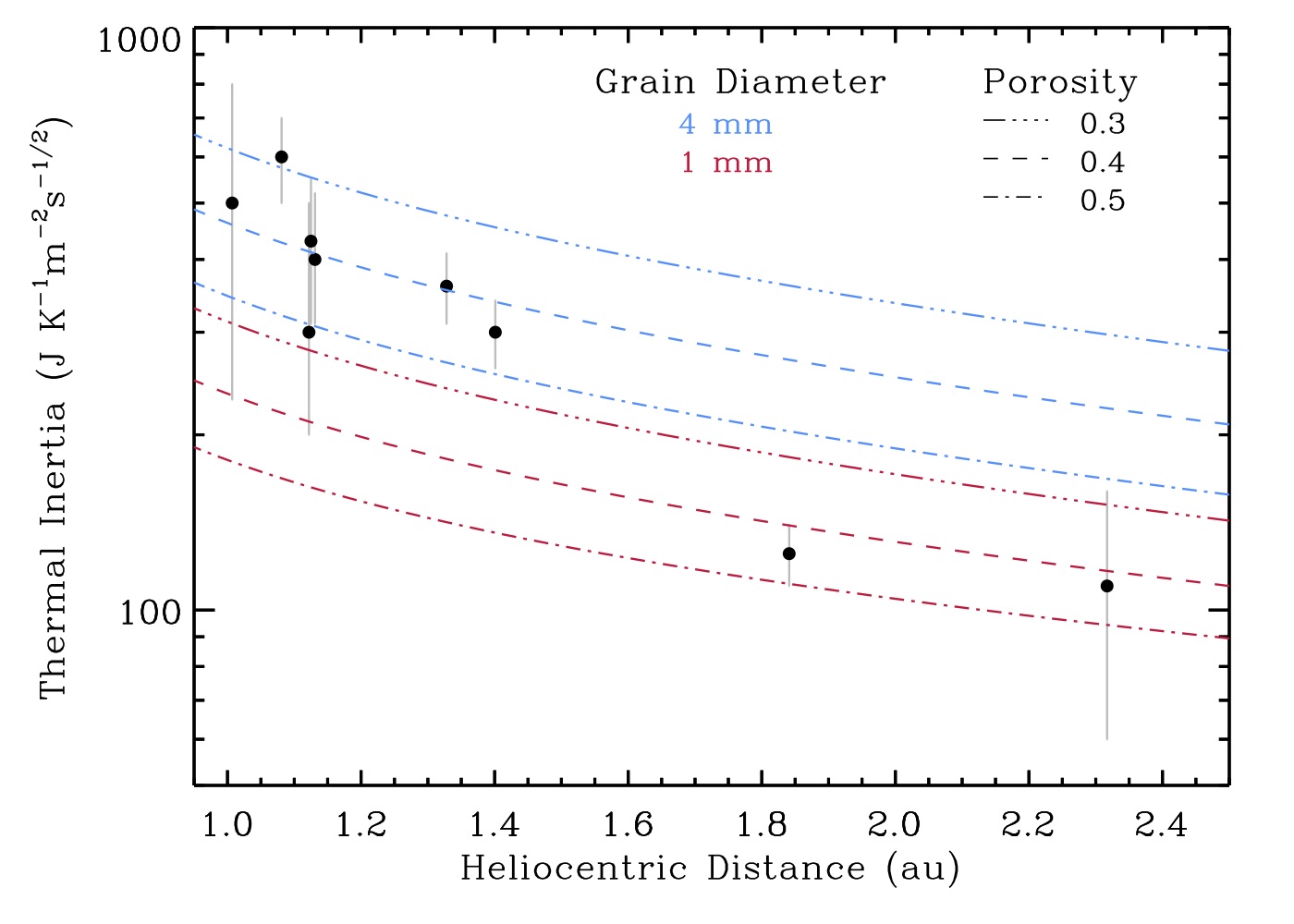

Regolith properties in the near-surface of asteroid can be inferred from the thermal inertia, Γ = √kρc. The effective thermal conductivity, k, is the most influential controlling factor in thermal inertia, as opposed to heat capacity (c) and bulk density (ρ). The effective thermal conductivity can expressed as a sum of the radiative conductivity and solid conductivity, which are controlled by the grain size and porosity of the regolith: specifically, the conduction through contacts through the regolith grains and the radiative transfer within the pores between them. Gundlach and Blum (2013) presented a thermal conductivity model that accurately models both these effects for planetary regoliths.

Because the radiative component of conductivity is temperature dependent (T3) it implies that thermal inertia is also temperature dependent. By extension, the strong inverse dependence that temperature has on heliocentric distance means that thermal inertia will increase with decreasing heliocentric distance. Rozitis et al., (2018) calculated this dependence for 3 NEAs: (1036) Ganymed, (1580) Betulia, and (276049) 2002 CE26. They found a wide variation in the variability, with Ganymed showing a strong dependence and Betulia showing a weak dependence.

The thermal inertia of Phaethon was previously estimated to be 600 ± 200 J m-2 K-1 s-1/2 by Hanus et al. (2018) and 880+580-330 J m-2 K-1 s-1/2 by Masiero et al. (2019). While Hanus et al. (2018) used a convex shape model derived from lightcurve inversion techniques, Masiero et al. (2019) used assumed a spherical shape. Furthermore these two different thermal inertia estimates were derived using two distinct datatsets: thermal emission spectrum from Spitzer and photometric data from IRAS and UKIRT Green et al (1995) was used by Hanus et al. (2018) and 5 epochs of WISE/NEOWISE photometry was used by Masiero et al. (2019). Both of these works alos reported diameter estimates of Phaethon (~5.1 and ~4.6 km) that are noticeably smaller than the reported effective diameter from delay-Doppler radar observations (5.5 - 6 km; Taylor et al. 2017).

Using a radar-derived shape model and thermal infrared observations from 10 observing epochs, we estimate Phaethon's thermal inertia for each epoch. We independently derive an effective diameter of ~5.5-5.6 km that is consistent with the radar observations and find that Phaethon's thermal inertia increases with decreasing heliocentric distance. Using the regolith thermal conductivity model presented by Gundlach and Blum (2013), we model the thermal inertia as a function of heliocentric distance for various grain sizes and porosities (Figure 1). We find that larger grain sizes are consistent with smaller heliocentric distances and smaller grain sizes are consistent with larger heliocentric distances.

Figure 1. Phaethon's thermal inertia as a function of heliocentric distance (black points) and modeled thermal inertia for different regoolith grain sizes and porosities.

We consider two other possibilities for Phaethon's regolith: 1) a depth-dependent layered model and 2) a two component latitude-dependnt model. The layered model consists of a fine-grained regolith covering solid bedrock and the two component model consists of two distinct grain sizes for each of Phaethon's northern and southern hemispheres. The effective thermal inertia of the layered regolith model exhibits a stronger dependence on heliocentric distance, as expected, but does not fit the observed thermal inertia estimates well. On the other hand, the model that consisters distinct grain sizes is very consistent with Phaethon's observed thermal inertia. We conclude that Phaethon's northern hemisphere consists of larger regolith grains compared to its southern hemisphere.

How to cite: MacLennan, E., Marshall, S., and Granvik, M.: Evidence for Regolith Heterogeneity on (3200) Phaethon, Europlanet Science Congress 2021, online, 13–24 Sep 2021, EPSC2021-804, https://doi.org/10.5194/epsc2021-804, 2021.

Introduction

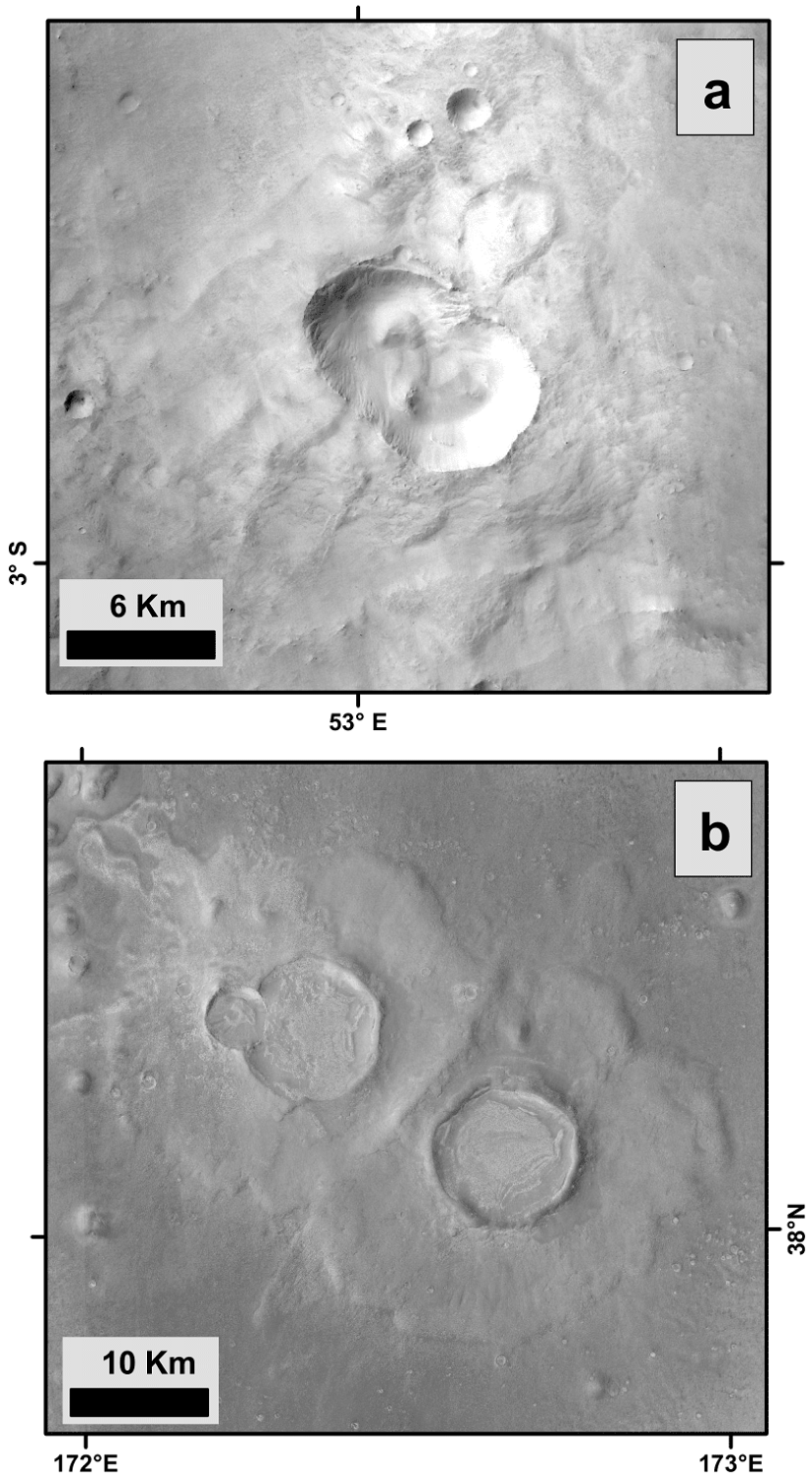

Planetary surfaces not protected by dense atmospheres suffered by many impacts by asteroids and comets, leaving craters as a reminders of it. Among all craters observed on surfaces of Earth, Mars, Moon, and Venus, about 3-4% are binary craters. It is believed they formed by the simultaneous impacts of the two components of binary asteroid systems.

Binary asteroids represent 15% of near-Earth asteroids, apparently at odd with the rate of binary craters on planetary surfaces. Miljkovic et al. showed with 3-D hydrocode simulations that only a fraction of impacts by binary asteroids create distinguishable binary craters, solving the apparent discrepancy with the fraction of binary craters of 3-4%. However, the few binary crater examples in have striking properties: nearly similar size and North-South orientation, unexpected from a population of binary asteroids displaying a typical size ratio of 0.3 and with a mutual orbit closely aligned with the ecliptic.

Survey and simulations