Abstracts with displays | ODAA

ODAA1 | Europlanet for Emerging Space Countries

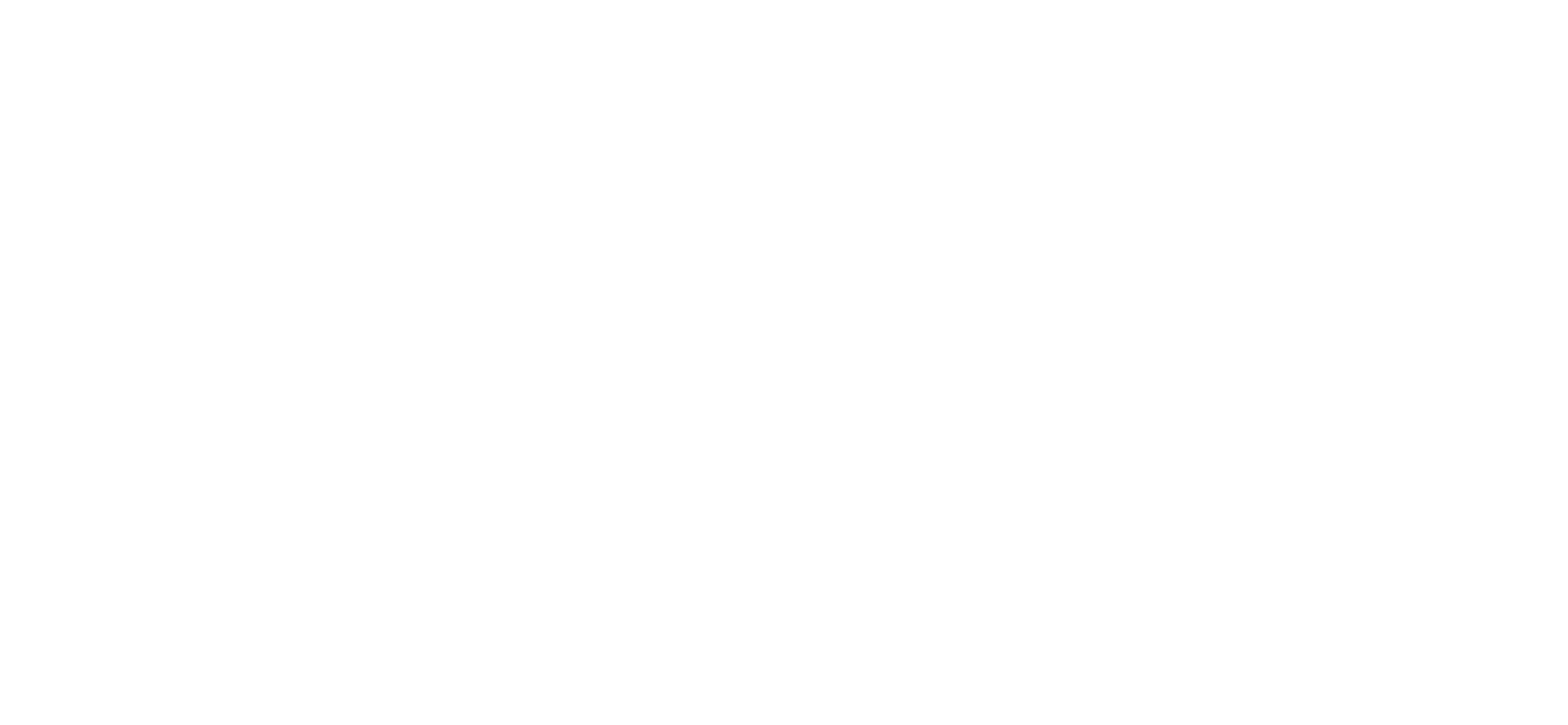

From March 16th to 26th 2022, for the first time in Togo, we organized an astronomy outreach event: “Togo under the stars”. This event is the result of a collaboration between the French association SpaceBus France and the Togolese association SG2D (Science Géologique pour un Développement Durable).

During two weeks, four French astronomers and six Togolese geologists traveled the country to reach a wide public. We visited schools, villages, and public squares and gave astronomy workshops in six cities: Kara, Sokodé, Atakpamé, Kpalimé, Aného and Lomé.

At each occasion, we proposed activities created by SpaceBus France, designed to be fun and interactive. These activities include a presentation of the Solar system using a scaled 3D printed model, a hands-on exercise on meteorites with different kinds of meteorites and terrestrial rocks to recognize them, an introduction to space travel and rocket science using lego models, and observations of both the Sun and the night sky using several telescopes.

In Lomé, we also provided an astronomy training for teachers of all levels, giving them educational tools and teaching resources developed by research institutions such as Europlanet Society, Paris Observatory, CNES, ESA, etc. These free resources and available on the internet can easily used to teach astronomy in classroom.

Togo under the stars has been a great success, reaching over 10.000 Togolese in total, with extremely positive feedback. This project, which was possible thanks to financial support from Europlanet, thus allowed the Togolese to have their first major astronomy outreach event. It offered a unique opportunity for the students to meet and exchange with astrophysicists and geologists, while the interaction with teachers insured a long-lasting impact on future generations.

More information : https://www.spacebusfrance.fr/le-togo-sous-les-etoiles

How to cite: de Assis Peralta, R. and Berard, D.: Togo under the stars: a science outreach tour for the Togolese, Europlanet Science Congress 2022, Granada, Spain, 18–23 Sep 2022, EPSC2022-1177, https://doi.org/10.5194/epsc2022-1177, 2022.

Planetary Geology and Astrobiology focused research have significantly grown in the last decades, where the US, European countries and China have been leading the path through NASA, ESA and CNSA space programs. This research has been more limited in South America, sometimes due to the lack of an explicit space program or where this program exists but developed at a smaller scale or focused on different goals. In spite of this, a growing number of scientists has been actively conducting research, directly or indirectly, related to these topics. Here is a brief and clearly biased and non-exhaustive summary shows how diverse this research is, taking some examples in Argentina and other countries such as Chile and Brazil, but being aware that other countries such as Colombia and Mexico also have a growing Planetary Geology and Astrobiology community.

Structural geology, geomorphology and tectonics in our planet is a matter of intense research in Argentina, particularly in the Andean region. Similar studies in other planetary bodies such as Mars, on the other hand, are more limited. In spite of this, it is worth mentioning the research conducted by Dr. Mauro Spagnuolo and colleagues of the IDEAN (Instituto de Estudios Andinos Pablo Groeber, Buenos Aires, Argentina, http://www.idean.gl.fcen.uba.ar/). This group has been actively collaborating and working on topics such as planetary mapping, geomorphology, structural geology and sedimentary processes of Mars and Titan surface.

The question of the possibility of life on other planets brings the need to be able to recognize extinct or extant life, particularly in the sedimentary record. The approach is to study how life develops in a diversity of environments, typically extreme environments, to understand how the signals of life are preserved in the sedimentary record (biosignatures). The study of microbial activity and their biosignatures has been the focus of research of Dr. Fernando Gomez and colleagues (https://fernandojgomez.github.io/FernandoJGomez/team/) from the CICTERRA (Centro de Investigaciones en Ciencias de la Tierra) and Dr. Douglas Galante (https://orcid.org/0000-0002-3265-2527) and Amanda Bendía (https://orcid.org/0000-0003-0042-8990) from the University of São Paulo (Brazil) by using a combination of sedimentolgical, biogeochemical and microbiological tools in order to explore the limits of life and its sedimentary record.

Dr. Pamela Such is a geologist from Argentina, and currently a SETI Institute research affiliate (https://www.seti.org/affiliates/pamela-such) who works mainly in developing the techniques and instrumentation necessary for the exploration of space resources. For example she collaborated with Dr. Pablo Sobron (SETI/NASA; Impossible Sensing Founder), testing LIBS laser and Raman instruments in environments of high UV and altitude and deficient oxygen levels in the Andes and with Dr. Mike Daly, OLA Instrument, OSIRIS-REx mission. She also has recently participated in the simulated mission to Mars, AMADEE 18, in the Oman desert. She has also recently led a project and research to study the feasibility of exposure and survival of Quinoa seeds to extra-planetary conditions to explore the development of crops during missions to the Moon and Mars.

The mineralogy and cosmochemistry of meteorites and its relevance to understand the formation of our Solar System has been the focus of intense research by Maria Eugenia Varela and colleagues of the ICATE (Instituto de Ciencias Astronómicas, de la Tierra y el Espacio) (https://icate.conicet.gov.ar/). In addition Dr. Varela is a member of the Argentinian Research Unit in Astrobiology (http://astrobioargentina.org/argentinian-research-unit-in-astrobiology/) where some scientists also explore the possibility of life in other planetary bodies. Another approach to meteorites and other space bodies has been developed by Dr Daniel Acevedo CADIC (Ushuaia, Argentina) and colleagues, by studying the numerous impact craters in Argentina and South America. For example, it is well known for their research in the Bajada del Cielo impact field in Chubut, southern Argentina. This research has been published in numerous papers and summarized in a really interesting book titled Impact Craters in South America (https://link.springer.com/book/10.1007/978-3-319-13093-4).

Dr. Giovanni Leone is an Italian geophysicist and volcanologist from the Atacama University, Chile (https://www.linkedin.com/in/giovanni-leone-73558185/?originalSubdomain=cl). His research includes Planetary Simulants, using the basaltic rocks from Atacama desert as a Moon and Mars geochemical analogues for testing rovers and carrying on experiments for future planetary settlements; Space Biomining, exploring the role of bacteria in low-water environments for the extraction of useful minerals (i.e. rare earth elements, copper, etc.); and Muography, the use of muons naturally produced by the interactions between galactic cosmic rays and atmosphere, for example, for the imaging of the internal structure of volcanoes. It is also worth mentioning his recent research on Mars surface and interior by combining geophysical and modelling techniques, as well as availability of important resources like water, and the studies about meteorites found in the Atacama Desert by Dr. Millarca Valenzuela (https://www.astrofisicamas.cl/millarca-valenzuela/).

Aside from the purely scientific approach to planetary geology, it worth to mention the activities developed by that SpaceBee Technologies (http://www.spacebeetech.com/), and its diverse team of geologists and engineers from Cuba and Argentina ( http://www.spacebeetech.com/team.html). This includes the development of a low-cost lunar rover named RoverTito, designed to contribute to the exploration of the Moon and to explore its potential for human habitability and for making the space accessible for future generations. Understanding the lunar regolith, the detection of structures such as lava tunnels or the distribution of solid water (ice) by using a set of geophysical techniques is between the goals of the SpaceBee Technologies project.

All these interesting efforts and contributions in planetary geology have been catalyzed by the individual and/or collective interest of some researchers and technology-focused teams, being the driving force of the curiosity for space exploration. Clearly, joining efforts into a more organized and better funded program where different institutions along South America can collaborate would increase the potential and collaborative research of all these researchers and engineers. This calls attention to the need to create the space for this discussion to take place and where people can share these activities and experiences and this may help to set the lines for a future planetary space program in South America.

How to cite: Gomez, F., Leone, G., Losarcos, J. M., and Santillan, F. A.: Planetary Geology and Astrobiology research in South America, Europlanet Science Congress 2022, Granada, Spain, 18–23 Sep 2022, EPSC2022-1246, https://doi.org/10.5194/epsc2022-1246, 2022.

ODAA2 | Diversity and Inclusiveness in Planetary Sciences

The EPEC (Europlanet Early Career) network was launched at EPSC in 2017, and since that day our community has grown exponentially. The idea was to create a friendly environment where early careers could meet, confront the complex dynamics of the academic career, and be involved in activities with the support of the Europlanet Society. In fact, the Europlanet Society itself felt the need of having a space where early-career researchers could gather and grow, and senior scientists played a fundamental role in supporting the new generations.

Today, EPEC reached that goal and is committed to building a strong network among young professionals by nurturing a supportive environment to develop various ideas within each themed working group (WG) and developing leadership skills. The EPEC community is open to all early-career planetary scientists and space professionals who obtained their last degree (e.g. MSc or PhD) less than 7 years ago.

Supervisors (and future supervisors) are of great help to spread the word about our community. By doing this, part of networking and understanding of the field will be complemented by the supervisor's perspective.

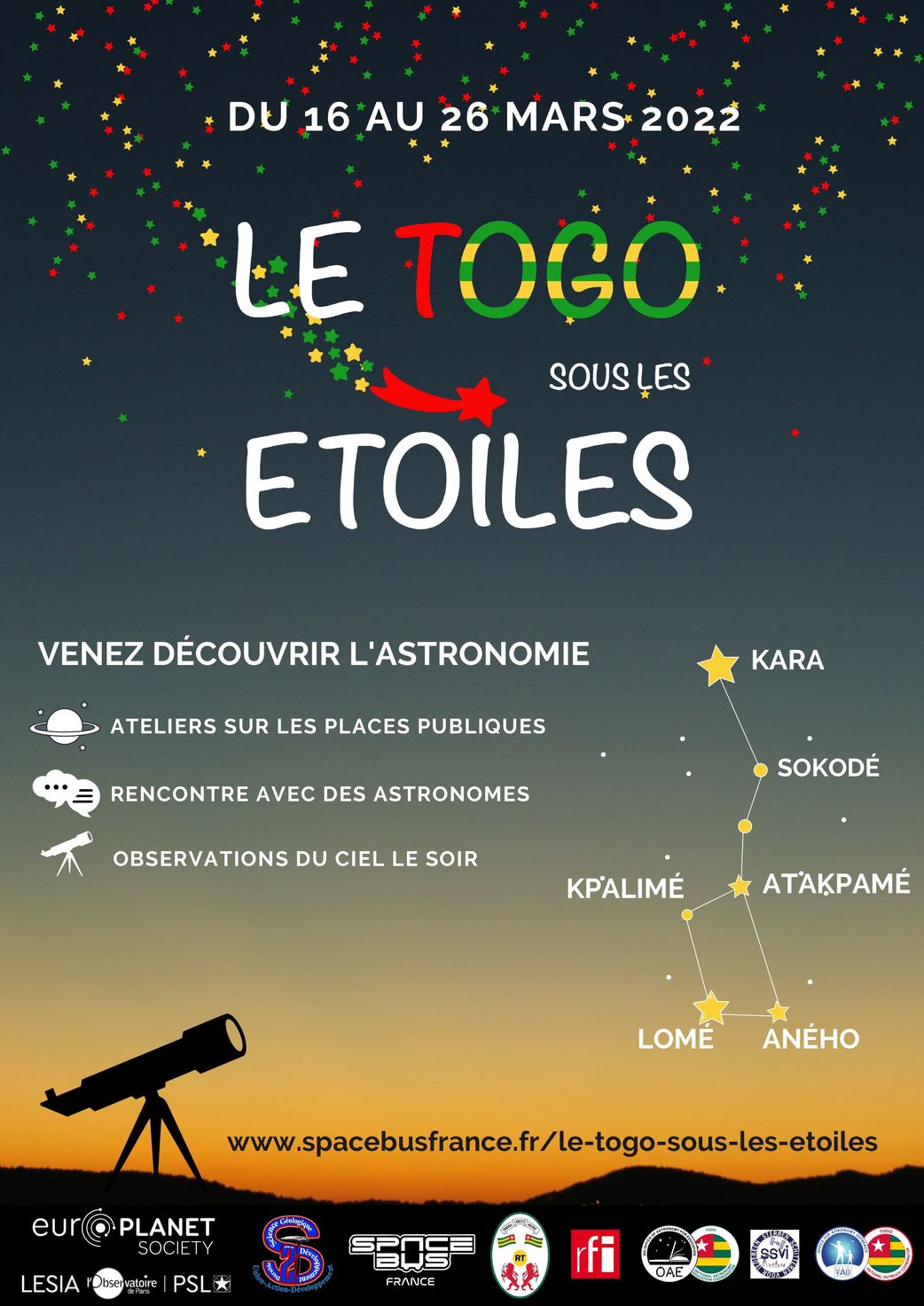

EPEC is structurally organized around 7 WGs (Fig.1): Communications, Diversity, EPEC@EPSC, Outreach, Annual Week, Early Career Support, and Future Research. Each WG, usually led by two Co-Chairs, works within its purview to best address the needs of early-career researchers and reflects on actions that can be implemented. This includes interviews, contests, and campaigns, continuously evolving thanks to new members and new ideas. We are working hard for every voice to be heard and this makes EPEC a very diverse and inclusive community.

Figure 1: EPEC is divided into 7 Working Groups (black outlined circles), each of them working on different topics (rimless circles).

The WGs are always looking for and welcoming other space enthusiasts who would like to contribute to the EPEC activities. Joining EPEC can be a great opportunity for early-career scientists.

In fact, EPEC offers occasions to meet peers from all across Europe and beyond as well as interact with the broader Europlanet Society committees and members. It is also a great chance to develop new skills of collaboration, leadership, project and team management - all of which will be of great value in their career, academic or not.

Every year, members of EPEC get together for two major events: the EPEC Annual Week (Fig. 2A) and the Europlanet Science Congress (EPSC) (Fig. 2B).

Fig. 2: A) Social event at the 2nd Annual Week, Lisbon, Portugal; B) Early career short courses at EPSC.

The Annual Week is an event that gathers early careers from everywhere in the world, where different seminars and workshops foster a healthy, collaborative, and interactive reflection on topics related to academia and the challenges that early careers face. For the last two years, it has been organized virtually, which reduced our interaction but gave us the unique chance to expand the event in an unprecedented way.

EPSC, on the other hand, is where EPEC members get a chance to present their scientific work to the entire community (including senior scientists) while connecting with other early careers through the EPEC@EPSC program.

Being involved in EPEC means also contributing to making the best of these two events and perhaps creating additional occasions to meet and work together.

Furthermore, EPEC supports early careers with open discussions about mental health (e.g. during the Annual Week), mentoring programs at EPSC, and the Motivational Journeys (Diversity WG) where scientists with different backgrounds share their stories and the obstacles they overcame. We are also going to launch our podcast soon, where we will invite guest speakers to highlight the relevance of a healthy routine during Ph.D. life and provide additional tips for young professionals to learn how to balance working hours and personal space.

This aspect is crucial, we can never stress enough the scientific community's need to be healthy, supportive, and let early careers express their difficulties in such a challenging career.

A few highlights of our current activities include:

- Our Profile Of The Month initiative, to highlight early-career scientists' journeys;

- Our Outreach Stories, that aim to inspire all researchers to share their science with the general public;

- Stairway to Space - EPEC’s brand new podcast;

- Video Contest PlanetaryScience4all, where the participants send a 4-minutes video about their PhD projects, and the winner gets free registration for the next EPSC;

- The early-career program at EPSC - look out for the sessions!

To contact EPEC, message us by email (epec.network@gmail.com).

Europlanet society members (of all career stages) and senior scientists in general are invited to follow EPEC on Twitter (@epec_epn) in order to help EPEC gain visibility among the early careers. More info on EPEC’s activities and how to keep up to date or get involved can be found on our website.

To join EPEC on Slack, scan the QR code:

(for early careers only)

How to cite: Luzzi, E., Belgacem, I., and Mirino, M. and the EPEC committee: The Europlanet Early Career (EPEC) Network: Building a Community to Support Junior Researchers, Europlanet Science Congress 2022, Granada, Spain, 18–23 Sep 2022, EPSC2022-586, https://doi.org/10.5194/epsc2022-586, 2022.

The planetary sciences and related fields are built on the foundation of sharing knowledge and making it accessible to all. In August 2020, Europlanet launched the Mentorship platform with the aim to support early career researchers. The platform is built to help early career scientists to develop expertise, ask questions and discuss career plans with the support of more established members of the planetary community. The success of the mentorship programme highlights the need for this programme and the potential role it can play in developing the individuals within our community who will advance planetary sciences over the coming years. On behalf of mentoring team, I will present the Europlanet mentorship platform and the current status of the programme. Europlanet 2024 RI has received funding from the European Union's Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under grant agreement No 871149.

How to cite: Stonkute, E.: Mentorship opportunities, Europlanet Science Congress 2022, Granada, Spain, 18–23 Sep 2022, EPSC2022-780, https://doi.org/10.5194/epsc2022-780, 2022.

Astronomy workshops were implemented in the 9th Primary School of Komotini which is an urban school located in the north-eastern part of Greece. The challenge that the school has to tackle is irregular attendance and school dropout. About half of the students come from families that face socioeconomic hardship, live in marginalised settlements in the city and belong to the Muslim minority of Thrace. Their school attendance is characterized by absenteeism that negatively affects the continuity of learning and the development of cognitive and social skills. These are followed by the loss of their self confidence, their alienation in the classroom and the school community. Thus the aim of the school is to be inclusive by accepting and attending to student diversity. Hence, the School administration and teacher staff has decided to implement interdisciplinary various workshops during the whole school year that include Storytelling, Drama, STEAM, Arts, Athletics, Pottery and Gardening. The Astronomy workshops were implemented collaboratively by a teacher, the Arts Teacher and the Music Teacher and in specifically included:

1. Planetarium workshop:

The School has a Planetarium which is a Geodesic Dome made out of white plastic film and a wooden skeleton. It consists of six pentagons, five hexagons and five half hexagons and has a diameter of 5m and height of 3m. It was made in 2018 by children to inspire other children about astronomy. Presentations were given to the whole school, six grades, eight classes, (132 students). The presentations which were focused on the solar system and famous missions were adjusted to their age. Free online videos, Stellarium and NASA’s Eyes were used for the presentations.

2. Music and movement workshop:

Next to the Planetarium is the School’s dance room. After the planetarium presentations the students participated in a music and movement workshop. They listened to sounds of the planets in our solar system and were enhanced by the teacher to kinetically express themselves and guided tο recreate in teams the orbits and rotations of the planets.

3. 3D Printing workshop:

In the ICT Lab students were introduced to 3D printing using Tinkercad a free web app. The School is an eTwinning STEM 3.0 School and was granted a 3D Printer in March. In teams students designed and 3D printed rockets, robotic spacecrafts and space suits.

4. Art workshop:

In the Art room and under the guidance of the Art teacher the students created a collective artwork inspired by the solar system and what they had learnt. Each class contributed by working on a specific part of the synthesis. The artwork is a 3D installation in the space of the corridor of the school that leads to the Planetarium. Polystyrene spheres balls were used for the 3D models of the Sun and planets and were painted with Fluorescent paints that can shine under UV black light. For the scale of the solar system of the artwork the sizes of the planets were taken in consideration in comparison with the Sun.

Acknowledgements

I would like to acknowledge the teachers and students of the 9th Primary School of Komotini.

How to cite: Molla, M., Amperiadis, P., and Kyriazopoulou, G. N.: Astronomy Workshops: Implementation in Greek Primary School, Europlanet Science Congress 2022, Granada, Spain, 18–23 Sep 2022, EPSC2022-1212, https://doi.org/10.5194/epsc2022-1212, 2022.

On 25 June 2022, the third edition of Soapbox Science takes place in Brussels. Soapbox Science is a public outreach platform that was initiated in London, UK in 2011 to promote women in science, and that was spread worldwide since then. Between 2011 and 2018, 40 cities hosted the initiative in not less than 8 countries over 4 continents, and in 2020, despite the pandemic, 56 events were organized in 14 countries around the world.

While the start of Soapbox Science Brussels was challenged by the COVID pandemic, a first virtual event was organised in the fall of 2020 via the YouTube and Facebook platforms [1]. Despite the difficulties related to the sanitary conditions, the first real-life edition of Soapbox Science Brussels finally took place in the heart of the Belgian capital in June 2021, following the standard format prescribed by the international Soapbox Science initiative. This event was a success, both with respect to the response of the scientific community and with regard to the interest of the public during the event. The third edition of Soapbox Science Brussels is currently in preparation, the list of selected speakers is already available and we just launched the campaign for the recruitment of volunteers.

In this communication, we present the development of the Soapbox Science initiative in Belgium. We describe the motivations, challenges, issues and opportunities encountered throughout the process, and how Soapbox Science is gradually taking its place in the Belgian context for the promotion of women in sciences.

Links:

Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/SoapboxScienceBrussels

Twitter account: @SoapboxscienceB

References:

[1] Pham, L. B. S., et al., Soapbox Brussels, une première en Belgique, Science connection nr. 65, August-september 2021;

in French: http://www.belspo.be/belspo/organisation/publ/pub_ostc/sciencecon/65sci_fr.pdf;

in Dutch: http://www.belspo.be/belspo/organisation/publ/pub_ostc/sciencecon/65sci_nl.pdf

How to cite: Piccialli, A., Bingen, C., Pham, L. B. S., Lamort, L., Lefever, K., and Yseboodt, M.: Soapbox Science Brussels: an outreach platform for the promotion of Women in Sciences in Belgium, Europlanet Science Congress 2022, Granada, Spain, 18–23 Sep 2022, EPSC2022-1224, https://doi.org/10.5194/epsc2022-1224, 2022.

ODAA3 | Professional-Amateur collaborations in small bodies, terrestrial and giant planets, exoplanets, and ground-based support of space missions

Introduction

Amateur observations of atmospheric features on the limb or night side of Mars proved their interest ([1], [2]). This led JL, specialist in aurorae, to collaborate with JLD, advanced amateur astronomer, to coordinate ten amateurs for attempting the first observation from Earth of aurora above the limb or on the night side of Mars.

Observations

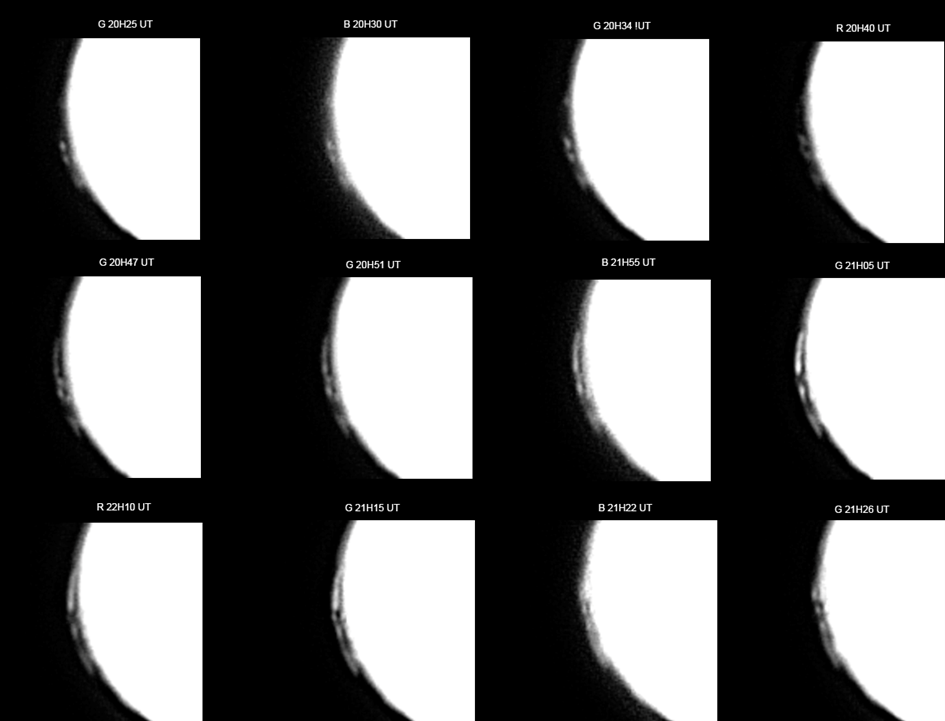

On Nov. 17th, 2020 (316° solar longitude), one of those amateurs, CP observed a suspect phenomenon over the night side of Mars. We identified an exceptional quality simultaneous observation by EB, over a three-hour timespan (fig. 1). Observation of the data set shows a 3000 km (from equator to South) detached layer on the night side, which seems to rotate with the planet on the day side, casting shadows before disappearing.

Fig. 1. Detached layer from 20H25 to 21H26 UT through red (R), green (G), and blue (B) filters. The disk is overexposed to better show the phenomenon.

Analysis

This feature could be an aurora, or a cloud system made from dust, H2O or CO2. With MV, specialist in Mars clouds, the collaborative team worked to characterize its altitude, its photometric properties, and its possible composition to determine its type.

a. Altitude

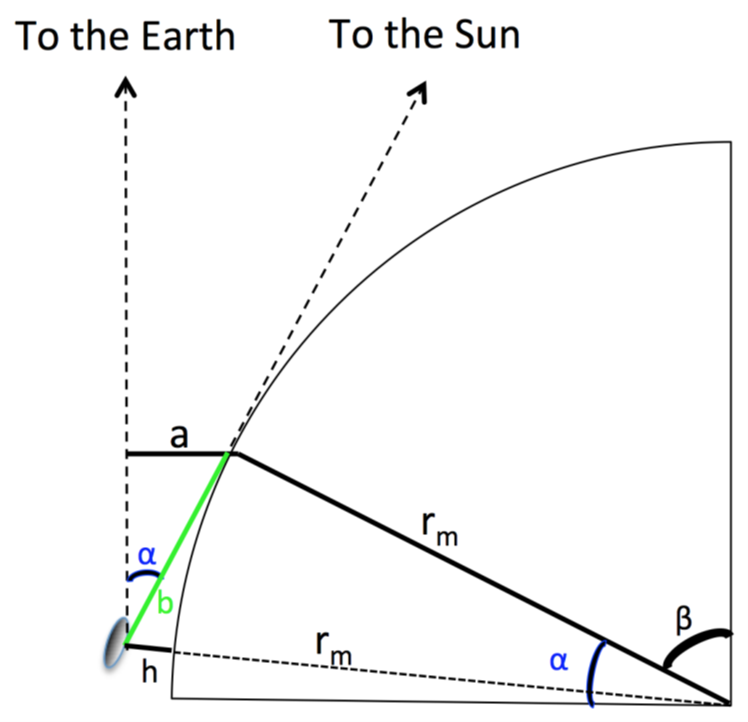

It was determined through several methods, using measures of the apparent position of the features on the images. Assuming the detached layer is seen at the time when the cloud emerges from night side, we used both a simple 2D method (fig. 2) and the 3D equations of [1] on the emergence images’ measures. Another method used the measure of the length of the shadow casted by the features. A last method measured the clouds fronts’ position following the features when it rotates on day side.

Amateurs MD, JLD and EB worked out those different methods which led overall to an altitude of 92 (+30/-16) km.

Fig. 2: Detached layer altitude determination with 2D geometric method.

b. Colour profile and albedo

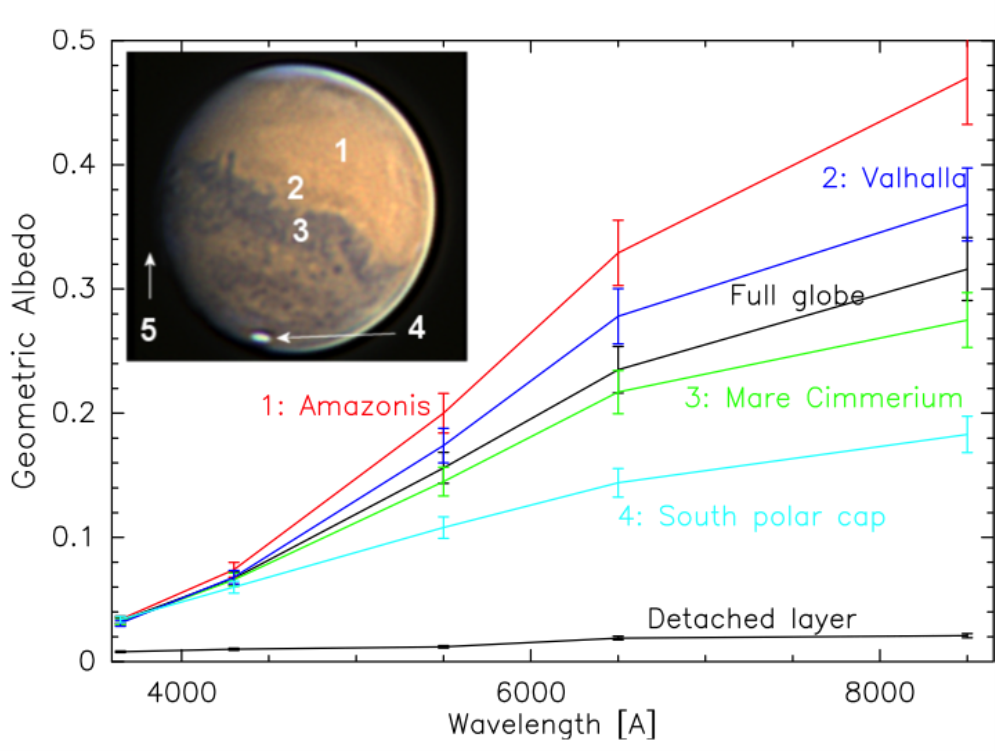

Amateur CP performed UBVRI photometry ([3]) of the planet and the layer. Reference stars observed at the same airmass as the observation were used. Different features were measured (bright and dark terrains, polar cap) as well as the overall globe, and one part of the detached layer. Fig. 3 shows the respective albedos measured, showing how the different zones measured reflects sunlight. The detached layer reflectance is twice brighter in red than in blue (while bright reddish terrain like Amazonis is five times).

Fig. 3. Albedo of different Martian structures compared to those of the full globe and of the observed detached layer.

c. Size and optical depth of particles constituting the layer

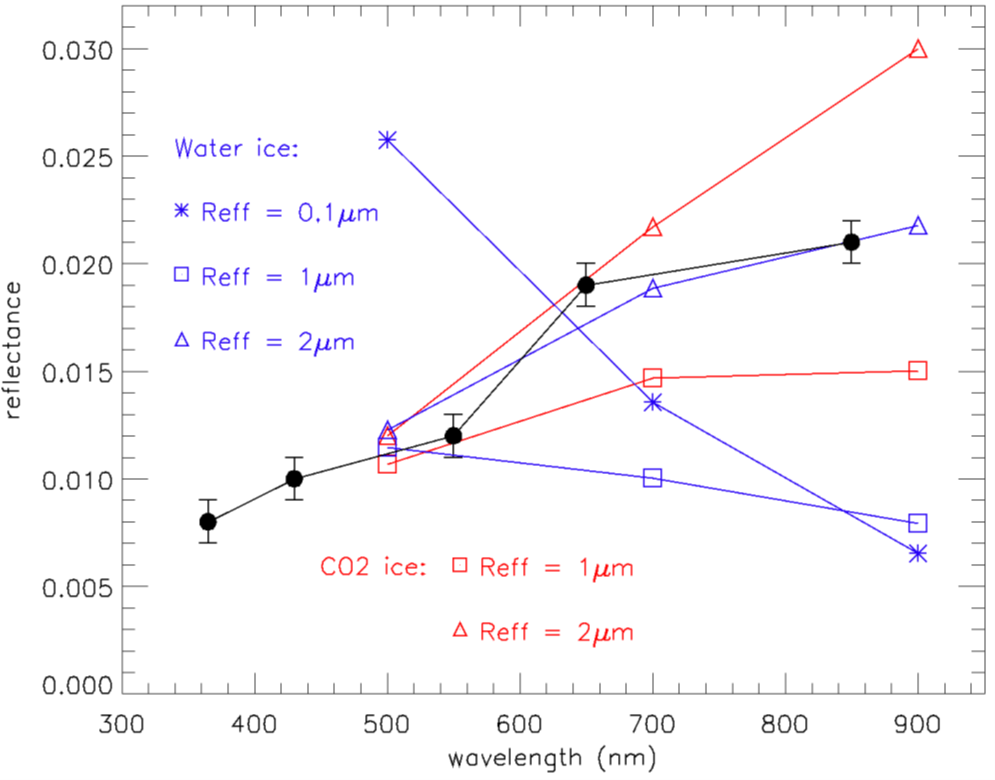

Colour profile shows that the layer scatters light over the whole spectrum, inconsistent with Rayleigh scattering or single wavelength emission, suggesting a layer consisted of dust aerosols or ice crystals.

Professional MV used [4] to model ice scattering reflectance of CO2 and H2O, resulting in fig. 4, showing that the reflectance profile of the layer is compatible with either 1-2µm CO2 or 2(+/-1) µm H2O particle sizes.

Fig. 4. Spectrum of the detached layer derived from figure 3 (black dots) compared to scattering models of CO2 (red) and H2O (blue) clouds with various ice crystal particle sizes models

Possible interpretation

a. Aurorae

JL predicted ([5]) 140km altitude for blue or green aurorae, and 160km for red aurorae, incompatible with this observation. Blue and green aurorae should be brighter than red ones, which is incompatible with the colour profile we evaluated. The quiet solar conditions on Mars during the observation time is also not compatible with the auroral assumption.

b. Dust clouds

A regional dust storm was present at the opposite side of the detached layer, but its colour is different from our detached layer’s. While high dust layers could reach an altitude of 80km, they are continuous from the ground to high altitude, unlike this observed layer.

c. Water ice

Water ice cloud at altitudes compatible with our observation are possible, in particular during global dust storms but with smaller ice particles (0.1-0.5µm). Nonetheless our observation could be an atypical water ice cloud, i.e. with large grain size despite its high altitude.

d. CO2 ice cloud

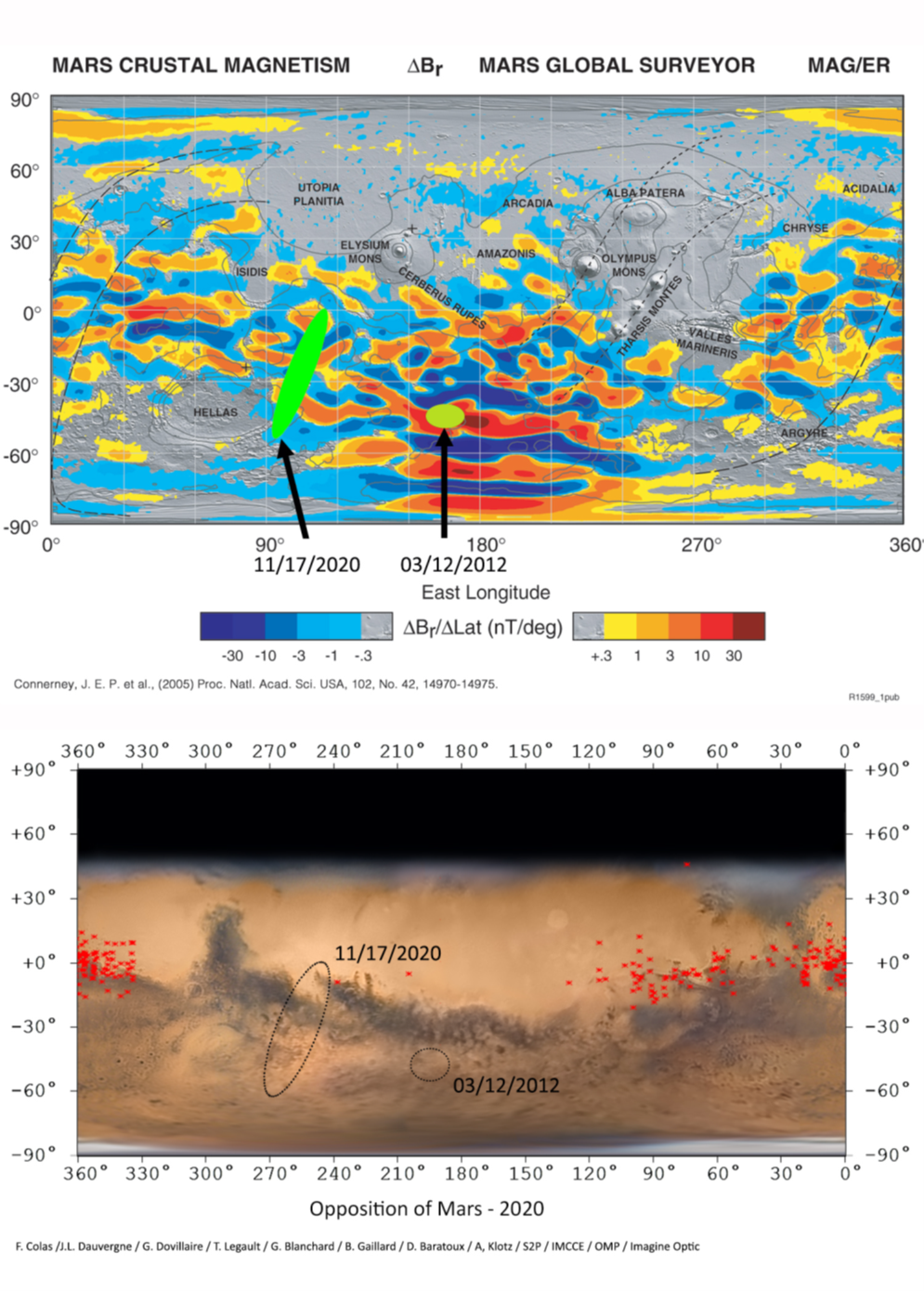

Typical mesospheric Martian day side CO2 ice clouds observed by probes are compatible with our observation in terms of particle size, but smaller (only hundreds of km wide), usually earlier in the year. From Mars Climate Database simulation, CO2 frost point could be reached at equator at the altitude of our observation, but at the limit which could be explained by gravity waves or our cloud being on the colder night side. Most of the system is outside of the common place for CO2 clouds (fig. 5). Our observation could be then an atypical CO2 ice cloud.

Fig. 5: Localisation of the observation compared to:

Top: Magnetic anomaly with two previous observations ([1]).

Bottom: previous CO2 clouds (red stars) projected on an albedo map.

Conclusion

This observation is located on the West border of the main Martian magnetic anomaly (fig. 5). This could show that cosmic rays, like on Earth or Titan, may have acted, through ionization of the atmosphere’s gas or dust particles, as condensation nuclei for the cloud.

For the first time a huge cloud system was observed from Earth, from its appearance on the night side to its dissipation on the day side only thanks to amateurs’ observations. While looking for aurorae, the study of this observation ruled out this explanation, favouring an ice cloud system either made of water or CO2, but atypical regarding some of its characteristics compared to previous observations. Its localization aside the large magnetic anomaly also indicates a possible explanation of its formation through cosmic rays ([6]).

Bibliography

[1] Sánchez-Lavega, A., et al. 2015, Nature

[2] Sánchez-Lavega, A., et al. 2018, Icarus

[3] Mallama, A. 2007, Icarus

[4] Vincendon, M., et al. 2011, Journal of Geophysical Research (Planets)

[5] Lilensten, J., et al. 2015, Planetary and Space Science

[6] Lilensten, J., et al. 2022, A&A (to be published)

How to cite: Delcroix, M., Lilensten, J., Dauvergne, J.-L., Pellier, C., Beaudouin, E., and Vincendon, M.: Amateur observation of an atypical martian atmospheric feature: when serendipity leads to identify an atypical cloud system, Europlanet Science Congress 2022, Granada, Spain, 18–23 Sep 2022, EPSC2022-43, https://doi.org/10.5194/epsc2022-43, 2022.

- Introduction

The colours of the belts, zones, and individual features of Jupiter are known to encounter significant variations either on short or long time scales. Those variations are the results of chemical or physical changes of the planet's meteorology that are of much interest. In order to try to precisely describe the colours of the planet beyond simple assessments (either visually or from images), the author presents results obtained with tools found in the scientific litterature, to characterize the colours of Jupiter during the apparition of 2021.

Scientific references showing examples of the same kind of work are [1] and [2]

- Method

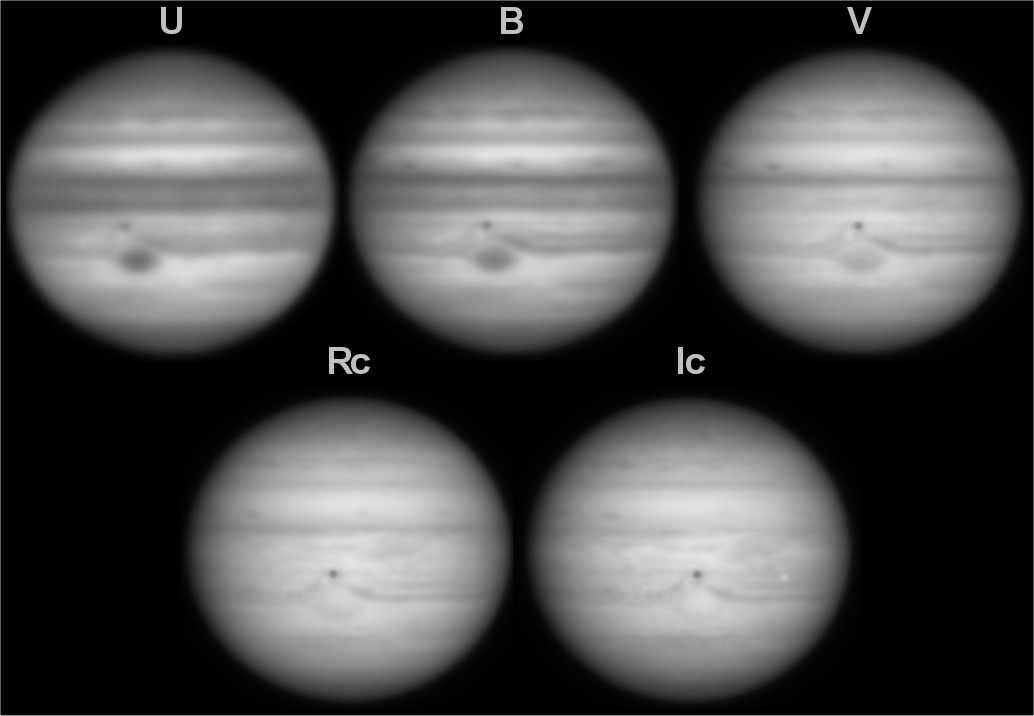

The planet is imaged with the method of lucky imaging, with a complete set of UBVRcIc plus z', CH4/890, and Y filters. Two cameras are used, one monochrome (ASI290MM from ZWO) and one colour, the ASI462MC, to benefit from its huge sensitivity in the near infrared wavelengths. Wavelet processing is not applied on the images. The geometric albedo of the planet is calculated for each one of the bands, thanks to the method exposed in EPSC2022-20, and the values are exploited with the following presentations. Figures 1 and 2 show photometric images taken respectively on September 6th, 2021, and September 23rd, showing the Great red spot.

- North-South scans

The goal is to characterize the photometric profile of the planet in direction of the polar axis, for each band of light. For this, images where longitudes estimated to be "representative" of the global state of the planet are used.

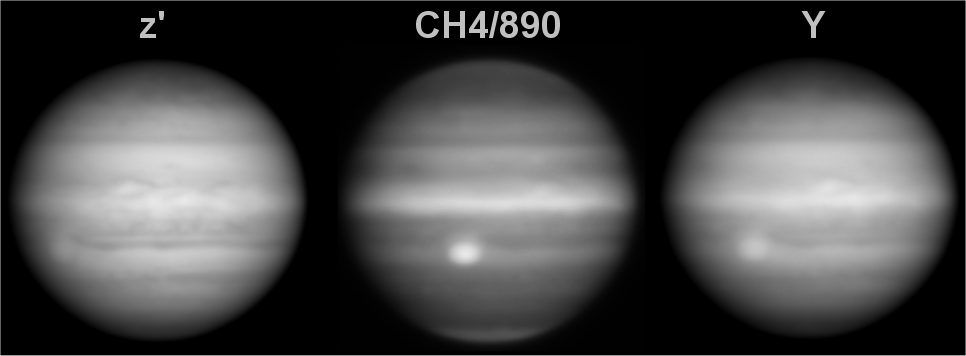

Another method would be to use images spanning a long range of longitudes. To diminish the sensitivity of a cut along a single line to local variations (i.e presence of individual spots...) the author used the software RSpec to select a wider range of longitudes around the central meridian (figure 3)

Images are not used directly: they are first sent into WinJupos and mapped onto equirectangular projection with planetographic latitude scale that allows to eliminate the moderate tilt of the globe, when present. The only thing not corrected is the small gradient of light brought by the polar tilt (the "winter" hemisphere being a bit less lit by the Sun). The photometric profile is calibrated in “wavelengths” from 0 to 180, to ease the building of the latitude scale (+90/-90°).

Finally, the profile is calibrated in intensity by calculating the albedo of a well identified region with the same method exposed in point 4 below. On figure 4 is an example of a final scan, all will be visible on the poster.

Ratios of some of those north-south scans can be made to provide colour indices that may reveal additionnal informations. Here is a B-Rc that may forms a good index of the colours of the planet, since the B band is where the maximum of variation occurs, when they are minimal in red (or IR) - figure 5:

- Spectra of individual features or regions

This work also allows to build spectra of individual features or regions, like the Great Red Spot, when measuring their particular albedo on the central meridian. Spectra will then only have a few points, depending on the number of filters used. To measure the albedo of individual features, the author used a circle of know radius (5 or 10 pixels...), noted the value of apparent brightness, and calculated what would be the brightness if this small area would be as large as the disk itself. Then by a simple rule of three, knowing what is the albedo of the global disk, it is possible to calculate the albedo of the feature of interest. An example of such spectra can be found in [2].

- References

[1] Mendikoa, I., Sanchez-Lavega,A., Pérez-Hoyos,S., Hueso,R., Rojas, J-F., Lopez-Santiago,J., "Temporal and spatial variations of the absolute reflectivity of Jupiter and Saturn from 0,38 to 1,7 µm with PlanetCam-UPV/EHU", Astronomy and Astrophysics, vol.607, november 2017.

[2] Simon AA, Wong MH, Rogers JH, Orton GS, De Pater I, Asay-Davis X, Carlson RW, Marcus PS, “Dramatic change in Jupiter's Great Red Spot from spacecraft observations”, The Astrophysical Journal Letters, 797:L31, 2014.

How to cite: Pellier, C.: The colours of Jupiter in 2021, Europlanet Science Congress 2022, Granada, Spain, 18–23 Sep 2022, EPSC2022-51, https://doi.org/10.5194/epsc2022-51, 2022.

Introduction

Taurus Hill Observatory (THO) [1], observatory code A95, is an amateur observatory located in Varkaus, Finland. The observatory is maintained by the local astronomical association Warkauden Kassiopeia. THO research team has observed and measured various stellar objects and phenomena. Observatory has mainly focused on exoplanet light curve measurements, observing the gamma rays burst, supernova discoveries and monitoring [2]. We also do long term monitoring projects [3].

The results and publications that pro-am based observatories, like THO, have contributed, clearly demonstrates that pro-amateurs are a significant resource for the professional astronomers now and even more in the future.

High Quality Measurements

The quality of the telescopes and CCD-cameras has significantly developed in 20 years. Today it is possible for pro-am's to make high quality measurements [4] with the precision that is scientifically valid. In THO we can measure exoplanet transits < 10 millimagnitude precision when the limiting magnitude of the observed object is 15 magnitudes. At very good conditions it is possible to detect as low as 1 to 2 millimagnitude variations in the light curve.

Season 2021 – 2022 Exoplanet Observations Review

A total of about 30 exoplanet observations and transit measurements were made during the observation season 2021/2022. All the measurements have been uploaded to the TRESCA database [5]. In total, about 250 light curve observations have now been sent directly to TRESCA from the Taurus Hill Observatory.

The season highlights that we consider to be most important could be the clear time deviations from the forecasts for a few TESS candidates, and in particular the Qatar-8b transit time deviations. The TOI1582.01b transit was not detected during the predicted period at all, so it differed quite a bit from the predicted one. These observations are presented in the following figures.

Figure 1: TOI1168.01b. The transit occurred about 1.7 hours earlier than predicted. Image: TRESCA.

Figure 2: TOI1455.01b. The transit occurred 1.6 hours earlier than predicted. Image: TRESCA.

Figure 3: TOI1582.01b. Not any clear transit was detected. Image: TRESCA.

Figure 4: TOI2152.01b. The transit occurred about 20 minutes earlier than predicted. Image: TRESCA.

Figure 5: Qatar-8b. The transit happened about three hours later than predicted. Image: TRESCA.

Adapting a New Camera for Measurements

The main equipment throughout the winter were Celestron C-14 SC telescope with a Paramount MEII tripod and an SBIG ST-8XME CCD camera with Baader Bessell BVRI photometric filters.

During the spring 2022, the ASI2600MM Pro CMOS camera was tested for the first time in Taurus Hill Observatory with a Chroma I filter connected to a Meade 16” ACX -telescope (with a Paramount ME tripod) for light curve measurements in the WASP-12b observations on March 31, 2022. At the same time, the object was also detected with an SBIG ST-8XME CCD camera connected to the Celestron C-14 SC -telescope. The results were very similar, so the CMOS camera is well suited for light curve measurements. An interesting feature of the transit of the WASP-12b was that immediately after the actual transit there is a very small dimming of 3 to 5 mmag, which lasts for about 30 minutes. MaxIm DL v6.08 software was used for imaging and image calibration, AIP4Win v2.4.10 software was used for photometric measurements.

The weather was even throughout the dark winter season from August to the end of April. The clearest nights were in March-April. The winter was very rainy overall, there was an exceptional amount of snow. In addition to exoplanet observations, Taurus Hill Observatory focused on comet imaging, DS imaging and the detection of GRB 220101A after-gamma glow, for which circular GCN 31356 [6] was published.

Acknowledgements

The Taurus Hill Observatory will acknowledge all the cooperation partners, Finnish Meteorological Institute and all financial supporters of the observatory.

References

[1] Taurus Hill Observatory website, http://www.taurushill.net

[2] A low-energy core-collapse supernova without a hydrogen envelope; S. Valenti, A. Pastorello, E. Cappellaro, S. Benetti, P. A. Mazzali, J. Manteca, S. Taubenberger, N. Elias-Rosa, R. Ferrando, A. Harutyunyan, V.-P. Hentunen, M. Nissinen, E. Pian, M. Turatto, L. Zampieri and S. J. Smartt; Nature 459, 674-677 (4 June 2009); Nature Publishing Group; 2009.

[3] A massive binary black-hole system in OJ 287 and a test of general relativity; M. J. Valtonen, H. J. Lehto, K. Nilsson, J. Heidt, L. O. Takalo, A. Sillanpää, C. Villforth, M. Kidger, G. Poyner, T. Pursimo, S. Zola, J.-H. Wu, X. Zhou, K. Sadakane, M. Drozdz, D. Koziel, D. Marchev, W. Ogloza, C. Porowski, M. Siwak, G. Stachowski, M. Winiarski, V.-P. Hentunen, M. Nissinen, A. Liakos & S. Dogru; Nature - Volume 452 Number 7189 pp781-912; Nature Publishing Group; 2008

[4] Transit timing analysis of the exoplanet TrES-5 b. Possible existence of the exoplanet TrES-5 c; Eugene N Sokov, Iraida A Sokova, Vladimir V Dyachenko, Denis A Rastegaev, Artem Burdanov, Sergey A Rusov, Paul Benni, Stan Shadick, Veli-Pekka Hentunen, Mark Salisbury, Nicolas Esseiva, Joe Garlitz, Marc Bretton, Yenal Ogmen, Yuri Karavaev,Anthony Ayiomamitis, Oleg Mazurenko, David Alonso, Sergey F Velichko; Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society, Volume 480, Issue 1, October 2018, Pages 291–301, https://doi.org/10.1093/mnras/ sty1615

[5] TRESCA; var2.astro.cz/tresca/transits.php?pozor=Veli-Pekka Hentunen&object=&page=1&lang=cz

[6] Hentunen V-P, Nissinen M, Heikkinen E; GCN 31356; https://gcn.gsfc.nasa.gov/gcn/gcn3/31356.gcn3

How to cite: Haukka, H., Hentunen, V.-P., Nissinen, M., Salmi, T., Aartolahti, H., Juutilainen, J., Heikkinen, E., and Vilokki, H.: Taurus Hill Observatory Season 2021 – 2022 Exoplanet Observations Review, Europlanet Science Congress 2022, Granada, Spain, 18–23 Sep 2022, EPSC2022-67, https://doi.org/10.5194/epsc2022-67, 2022.

The cloud discontinuity of Venus is a planetary-scale phenomenon known to be recurrent since, at least, the 1980s. It was initially identified in images from JAXA’s orbiter Akatsuki. This disruption is associated to dramatic changes in the clouds’ opacity and distribution of aerosols and is interpreted as a new type of Kelvin wave. The phenomenon may constitute a critical piece for our understanding of the thermal balance and atmospheric circulation of Venus. The reappearance on the dayside middle clouds four years after its last detection with Akatsuki/IR1 is reported in this work. We characterize its main properties using exclusively near-infrared images from amateur observations for the first time. The discontinuity exhibited tempοrаl variations in its zonal speed, orientation, length, and its effect over the clouds’ albedo during the 2019/2020 eastern elongation in agreement with previous rеρorts. Moreover, amateur observations are compared with simultaneous observations by Akatsuki UVI and LIR confirming that the discontinuity is not visible on the upper clouds’ albedo or thermal emission. While its zonal speeds are faster than the background winds at the middle clouds, and slower than winds at the clouds’ top, it is evidencing that this Kelvin wave might be transporting momentum up to upper clouds.

How to cite: Kardasis, E., Peralta, J., Maravelias, G., Imai, M., Wesley, A., Olivetti, T., Naryzhniy, Y., Morrone, L., Gallardo, A., Calapai, G., Camarena, J., Casquinha, P., Kananovich, D., MacNeill, N., Viladrich, C., and Takoudi, A.: Results from the professional-amateur collaboration to investigate the Cloud Discontinuity phenomenon in Venus’ atmosphere, Europlanet Science Congress 2022, Granada, Spain, 18–23 Sep 2022, EPSC2022-208, https://doi.org/10.5194/epsc2022-208, 2022.

Introduction

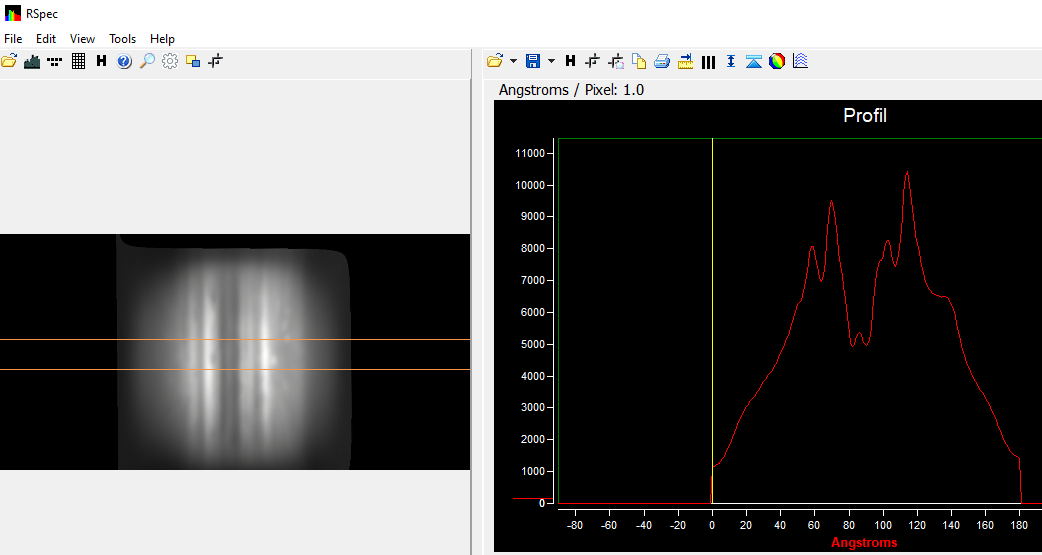

The extended portion of NASA’s Juno mission began on 1 August 2021 and will continue through September 2025. The extended mission expands Juno’s science goals beyond those of the prime mission, as noted at the last EPSC (Orton et al. EPSC2021-58). Atmospheric studies will continue to be among the foremost of science goals and an area in which the world-wide community of Jupiter observers can provide significant contextual support. Juno’s remote-sensing observations will take advantage of the migration of its closest approaches (“perijoves” or PJs) toward increasingly northern latitudes. The observations should include close-ups of the circumpolar cyclones and semi-chaotic cyclones known as “folded filamentary regions”. A series of radio occultations will provide vertical profiles of electron density and the neutral-atmospheric temperature over several atmospheric regions. The mission will also map the variability of lightning on Jupiter’s night side.

Physical Details of the Mission

The sequence of orbits and key investigations of the primary and extended missions are shown in Figure 1. We note that on PJ34, the orbital period was reduced from 53 days to 43-44 days. It will be reduced shortly after this meeting on PJ45 to 38 days and again on PJ57 to ~33 days.

Figure 1. Progression of Juno orbits viewed from above Jupiter’s north pole with respect to local time of day. “PJ” designates a “perijove”, the closest approach to Jupiter on each numbered orbit. Following a Ganymede flyby on PJ34 (green orbit), the orbital period decreased from 53 days to 43-44 days (green + blue orbits). The “Great Blue Spot” (blue) orbits map an isolated patch of intense magnetic field. Following a close Europa flyby on PJ45 (aqua orbit), the period will decrease to ~38 days (orange orbits). Following close flybys of Io on PJ57 and PJ58 (black orbits) the period will decrease to ~33 days (red orbits). In reflected sunlight, Jupiter will mostly appear as a crescent at perijoves following PJ58.

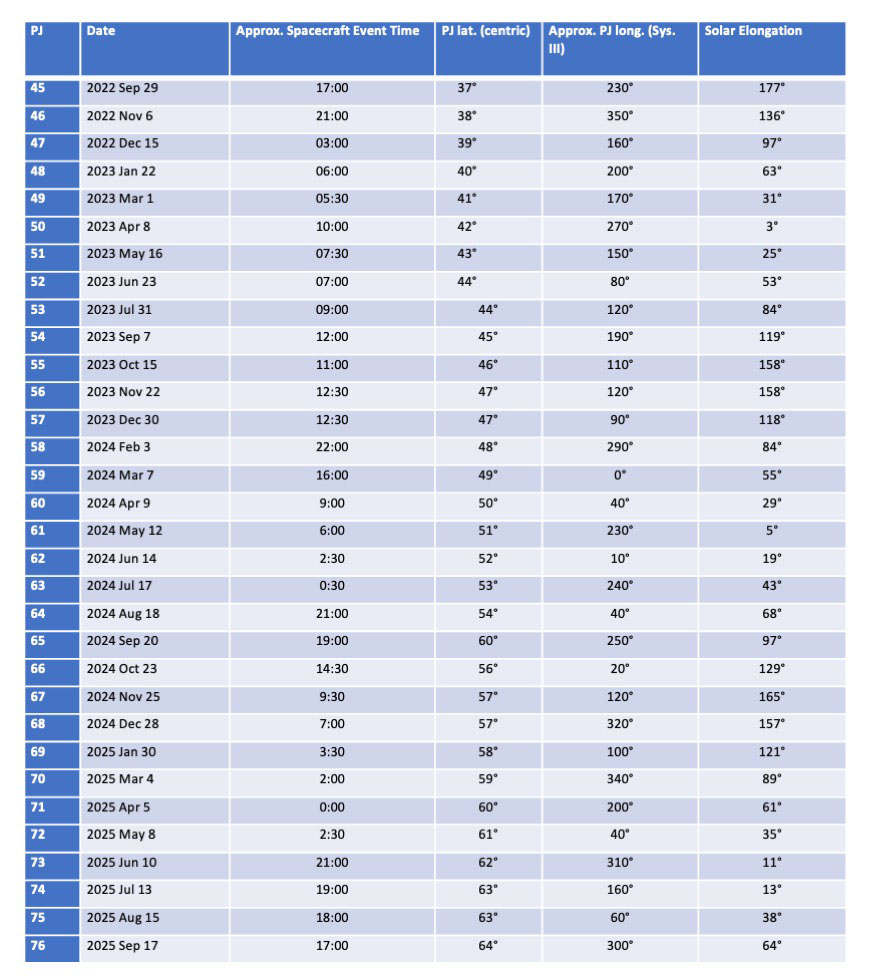

Some characteristics of perijoves of the extended mission are shown in Table 1. We caution that while the day of year for the perijoves is reasonably fixed, the exact times may change by hours in either direction and the longitudes will change accordingly. Timing for later orbits up to PJ76, may be affected by currently unmodeled anomalies in satellite masses that could change dates and times.

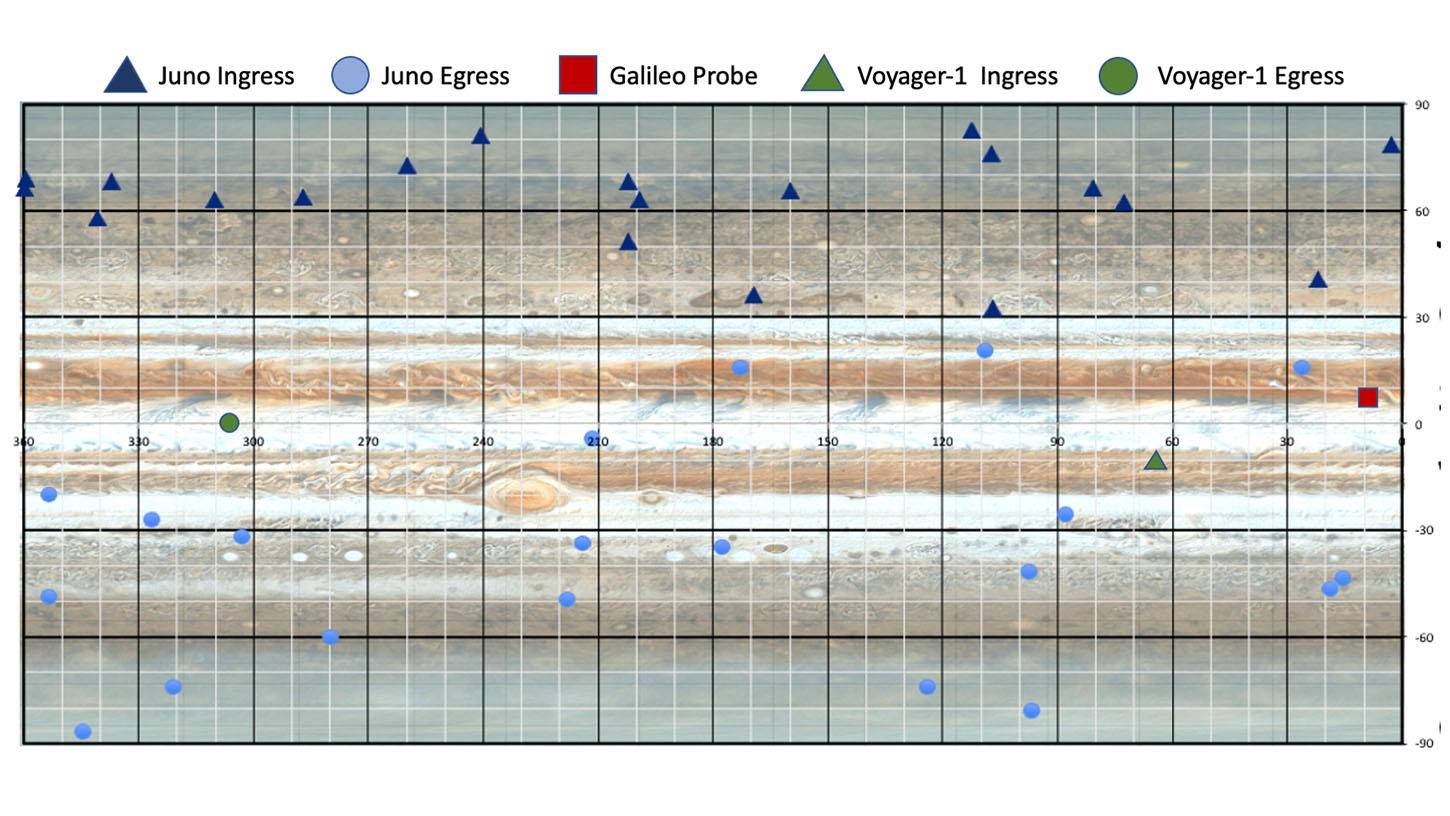

Figure 2. Expected latitudes and longitudes to be measured by the 20 radio occultations of the Juno spacecraft between PJ52 and PJ77. Locations of ingress lie largely in the northern hemisphere - locations of egress in the southern hemisphere. Locations of the Galileo Probe and Voyager-1 radio occultations are also shown for reference.

Role of Amateur Astronomers

We’ve noted in the past at previous EPSC meetings how amateurs can contribute to the Juno mission via their collective world-wide 24/7 coverage of Jupiter. This applies also to the cadre of professional astronomers supporting the Juno mission and its reconnaissance of the Jupiter system over a broad spectral range. In the past, these have alerted observers to strong interactions between the Great Red Spot and smaller anticyclones (Sanchez-Lavega et al. 2021. J. Geophys. Res. 126, e006686) and the occurrence and evolution of prominent and unusual vortices, such as “Clyde’s spot” (Hueso et al. 2022. Icarus 380,114994). During the last apparition, observations were made with the NASA Infrared Telescope Facility (IRTF) that showed slow-moving bright patches in the Equatorial Zone (EZ) that were observed more continuously among the amateur community with 890-nm (“methane”) filters. We also identified an intense 5-µm spot detected using IRTF imaging that coincided with an unusually dark spot in amateur methane-filtered images. The continued tracking of outbreaks in the southern part of the North Equatorial Belt (NEB) also greatly informed the Juno team and supporting astronomers regarding the systematic longitudinal distribution of outbreaks and the range of atmospheric features they generate. A perijove-by-perijove summary of Juno-supporting observations – past, current and planned - is available at the following web site: https://www.missionjuno.swri.edu/planned-observations.

We want to emphasize that by PJ50, Juno’s perijoves will have migrated to a part of the planet that is not in sunlight. At that point and through the end of the mission, images from this community will be extremely useful to order to provide a context for several investigations. One of these will be chief on JunoCam’s agenda during this part of the mission: searches for lightning. But similar contextual information will be sought for measurements of thermal emission from the JIRAM instrument’s high-resolution maps of 5-µm emission, as well as the Microwave Radiometer (MWR) measurements of thermal emission from the deep atmosphere. Although the highest spatial resolution from these instruments will include high northern latitudes (see Table 1) that are not well resolved by small telescopes, measurements of mid-northern latitudes will continue to be made when JunoCam will not be able to provide a visual context.

Table 1. Current estimates for Juno extended mission perijoves PJ45-PJ53. Timing for orbits PJ54 onward may be affected by currently unmodeled anomalies in satellite masses that could change dates and times. Accordingly we list perijove times to the nearest half hour and longitudes to the nearest 10°. Orton et al. (EPSC2021-58) presented information for previous perijoves.

How to cite: Orton, G., Momary, T., Brueshaber, S., Hansen, C., Bolton, S., and Rogers, J.: The Juno Extended Mission: A Call for Continued Support from Amateur Observers, Europlanet Science Congress 2022, Granada, Spain, 18–23 Sep 2022, EPSC2022-769, https://doi.org/10.5194/epsc2022-769, 2022.

Abstract

As a potential pro-am complement to professional Jovian ammonia observations, continuum-divided 645 nm ammonia absorption observations were made using a small telescope. This paper presents highlights of observations during 2020 and 2021. If this low-cost technique can be promulgated among amateurs, then routine atmospheric monitoring of Jupiter would reach a new level of sophistication.

Introduction

New microwave and MIR observations, along with models, reveal much about Jupiter's ammonia cycle at depth. For example, the Juno MWR instrument permits the retrieval of the average ammonia abundance to a depth of 100 bar [1]. Additional recent work has used MIR observations to probe to depths of several bars [2-3]. Similarly, there have been efforts at global retrievals using hyperspectral imaging in the optical and NIR [4-5]. Complementing these efforts have been notable improvements in the understanding of the ammonia optical and NIR absorption bands [6]. Slit spectrometry data extend an already long record [7]. Finally, recent work has shown the efficacy of imaging Jovian upper tropospheric features in the 645 nm ammonia absorption band [8], which the current paper expands upon.

Observations

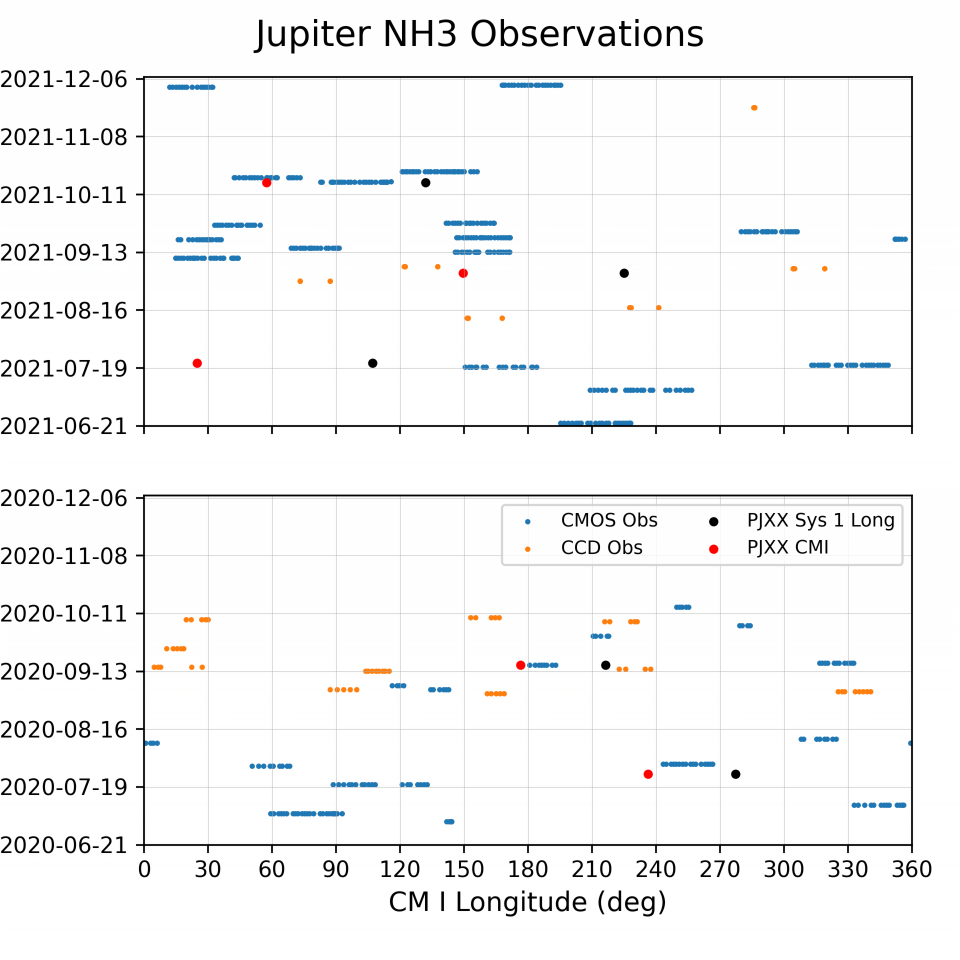

Thirty-nine usable observing sessions were carried out during 2020-2021 from the author’s observatory in Denver, Colorado. Fig. 1 shows the observations versus System I longitude. It also depicts Juno perijoves. During July and September 2020 observations overlap with the longitudes observed by Juno on PJ28 and PJ29. The best adjacent observations in 2021 occurred in October (PJ37). Also, near Juno perijove (PJ36), the System 1 longitude range of 140-180 degrees was observed multiple times. This allows for observing the evolution of features in the Equatorial Zone (EZ).

Figure 1: Observing sessions in 2020 (bottom) and 2021 (top). Individual images contributing to ammonia absorption observations are shown (CMOS: blue; CCD: orange). Juno perijove longitudes (Sys. 1) and Earth-facing central meridians (Sys. 1) at perijove are indicated in black and red respectively.

Highlights

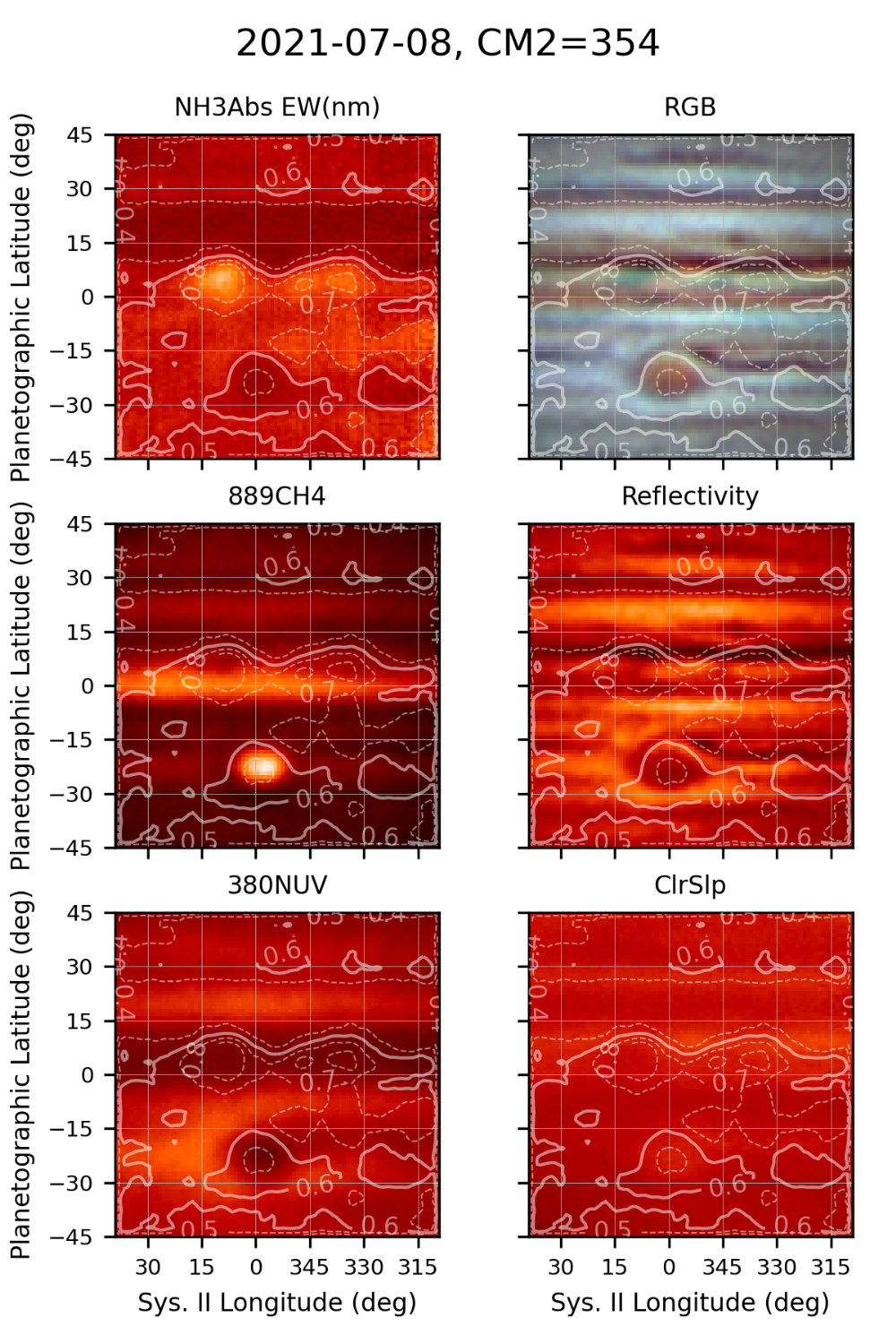

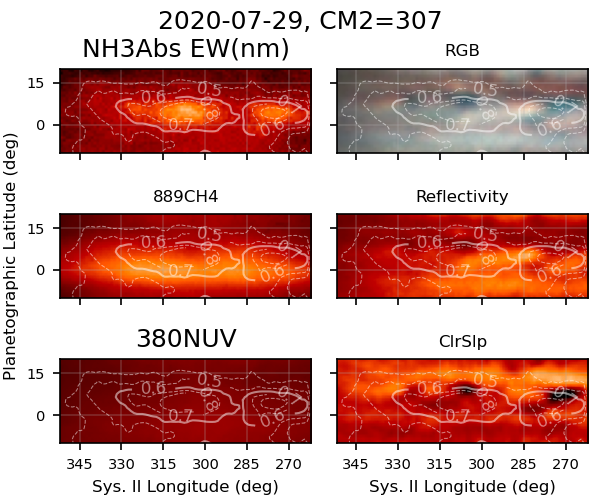

Fig. 2 shows the NEB has reduced ammonia absorption, the EZ is enhanced, and the GRS is reduced. Note the correlation and lack of correlation with obvious visible features. There is a reduction correlated with the GRS, but the reduced absorption region from about 15-25N includes both bright and dark features.

Figure 2: Ammonia absorption and context maps. Brightness scaling is arbitrary and adjusted for visual effect. Contour levels are estimated ammonia absorption equivalent width in nm. “ClrSlp” is relative color slope with redder areas shown as brighter.

Fig. 3 shows the EZ and NEB, including ammonia absorption enhancements near plumes and dark features. Dark features look deep into the atmosphere and the bright plumes represent high clouds.

Figure 3: Same as Figure 4 but focused on the northern EZ.

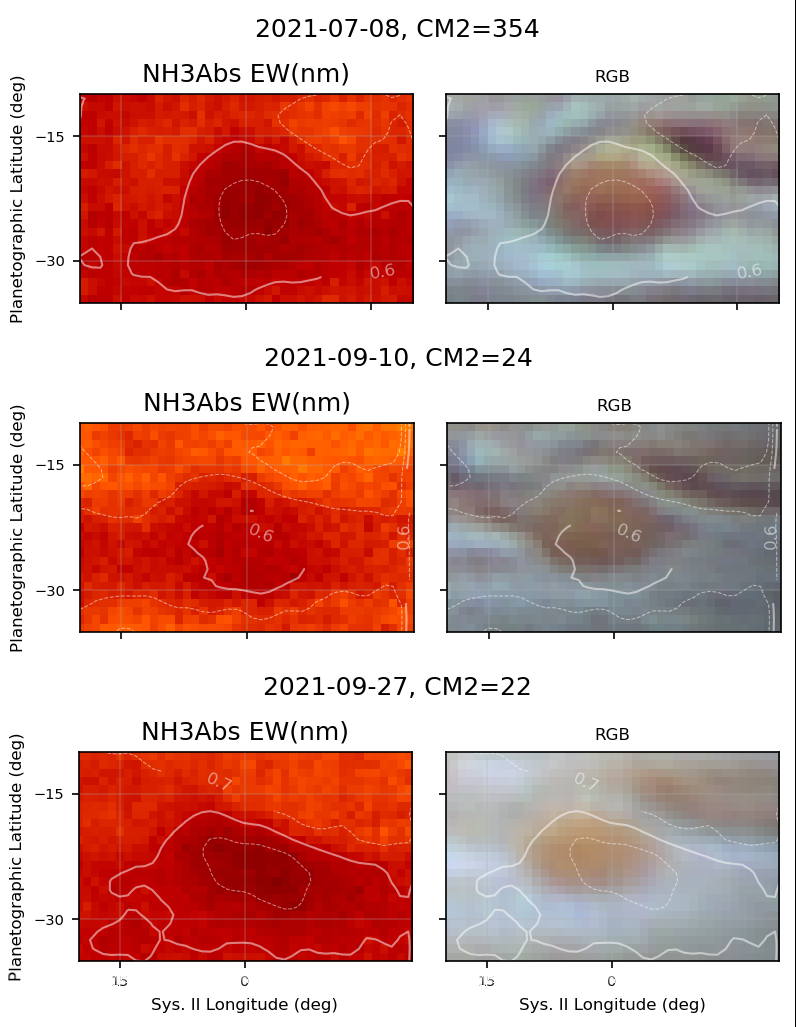

The GRS is shown from July through September 2021 in Fig. 4. Ammonia absorption is reduced over the GRS due to the high-altitude scattering layer there. This reduction has also been noted in spectroscopic observations [7].

Figure 4: Reduced ammonia absorption over the Great Red Spot at three epochs in 2021.

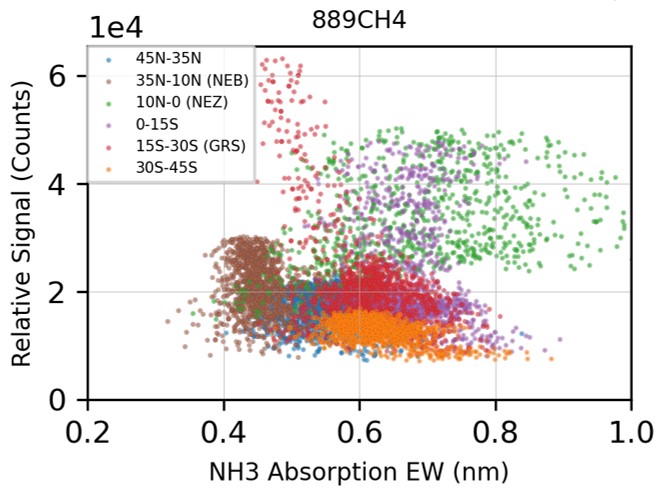

Retrieval Potential

A scatter plot of 889 nm brightness versus 645 nm NH3 equivalent width (Fig. 5) shows the distributions of different latitude bands. High brightness in the methane band indicates higher cloud tops, which leads to a shorter absorption path. Thus, the GRS (high brightness red ‘tail’ in the 15-30S band) has a high reflecting layer. The ammonia EW is low, consistent with the short absorption path. The NEB (brown) shows uniformly low methane brightness, indicating deeper cloud tops, but also shows low ammonia absorption. This supports an actual depletion in ammonia abundance.

Figure 5: Scatter plot 889 nm methane relative signal versus 645 nm ammonia equivalent width for different meridional bands (2021-07-08, CM2 354 deg).

The scatter plot analysis suggests that a simple Reflecting Layer Model might provide meaningful first-order retrievals of atmospheric properties [9]. The goal during 2022 will be to retrieve reflectivity, cloud top pressure, and ammonia abundance by extending this model. In addition, observations will be shared on amateur collaboration websites.

Summary and Conclusion

This paper highlights two years of continuum-divided ammonia absorption imaging of Jupiter. The method shows detail inaccessible with other imaging techniques. The observations will be tested for utility in a simple atmospheric retrieval model and will be shared during the 2022 apparition.

References

[1] Guillot, T., et al. (2020), Storms and the Depletion of Ammonia in Jupiter: II. Explaining the Juno Observations, Journal of Geophysical Research (Planets), 125, e06404.

[2] Fletcher, L. N., et al. (2020), Jupiter's Equatorial Plumes and Hot Spots: Spectral Mapping from Gemini/TEXES and Juno/MWR, Journal of Geophysical Research (Planets), 125, e06399.

[3] Fletcher, L. N., et al. (2021), Jupiter's Temperate Belt/Zone Contrasts Revealed at Depth by Juno Microwave Observations, Journal of Geophysical Research (Planets), 126, e06858.

[4] Braude, A. S., P. G. J. Irwin, G. S. Orton, and L. N. Fletcher (2020), Colour and tropospheric cloud structure of Jupiter from MUSE/VLT: Retrieving a universal chromophore, Icarus, 338.

[5] Dahl, E. K., N. J. Chanover, G. S. Orton, K. H. Baines, J. A. Sinclair, D. G. Voelz, E. A. Wijerathna, P. D. Strycker, and P. G. J. Irwin (2021), Vertical Structure and Color of Jovian Latitudinal Cloud Bands during the Juno Era, The Planetary Science Journal, 2, 16.

[6] Irwin, P. G. J., N. Bowles, A. S. Braude, R. Garland, S. Calcutt, P. A. Coles, S. N. Yurchenko, and J. Tennyson (2019), Analysis of gaseous ammonia (NH3) absorption in the visible spectrum of Jupiter - Update, Icarus, 321, 572.

[7] Teifel', V. G., V. D. Vdovichenko, P. G. Lysenko, A. M. Karimov, G. A. Kirienko, N. N. Bondarenko, V. A. Filippov, G. A. Kharitonova, and A. P. Khozhenets (2018), Ammonia in Jupiter's Atmosphere: Spatial and Temporal Variations of the NH3 Absorption Bands at 645 and 787 Nm, Solar System Research, 52, 480.

[8] Hill, S. (2021), Experimental Observations of Jupiter in the Optical Ammonia Band at 645 nm, edited, pp. EPSC2021-2260.

[9] Mendikoa, I., S. Pérez-Hoyos, and A. Sánchez-Lavega (2012), Probing clouds in planets with a simple radiative transfer model: the Jupiter case, European Journal of Physics, 33, 1611.

How to cite: M Hill, S. and Rogers, J.: Jupiter Ammonia Absorption Imaging: Highlights 2020-21, Europlanet Science Congress 2022, Granada, Spain, 18–23 Sep 2022, EPSC2022-802, https://doi.org/10.5194/epsc2022-802, 2022.

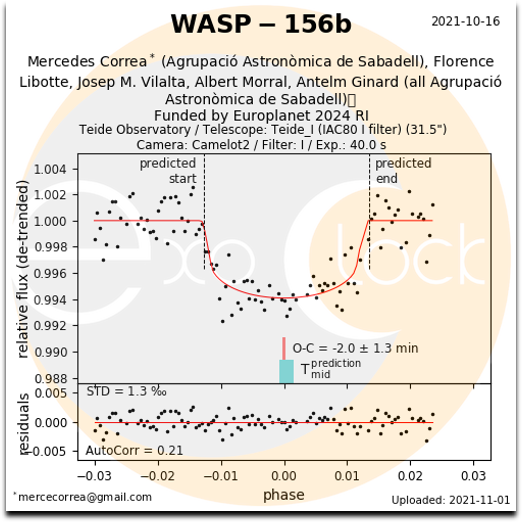

I this talk I will present the process to get observations on a Europlanet network telescope for an exoplanet transit. The steps of obtaining and also analysing the exoplanet transit light curve will be described. These data are used for the future Ariel space mission organised by ESA. Moreover, the talk will describe the process of writing the proposal for the request of the observation and in the particular case to the Instituto de Astrofísica de Canarias. In parallel, I will explain the way to obtain the funding for the telescope cost by Europlanet organization. Then I will go through the observations themselves and the live decisions regarding signal to noise, exposure time and so on in order to maximize the success probability. Then a report regarding the progress of the observation(s) is written and sent to the organisers. After the part of obtaining the observation, I will describe he process of analysing the images with the ExoClock HOPS software. Details will be provided on how to work with it, how to choose comparison stars, how to get the best light curve and to determine the exact moments of the ingress of the transit and the egress of it. Once the light curve is produced, it is uploaded in the ExoClock website and after reviewing it gets published at the ExoClock database. I would like to highlight that main partners in this work are two women, what is not so common in this field.

How to cite: Libotte, F. and Correa, M.: Exoplanet observations: amateur experience from the Europlanet Telescope network, Europlanet Science Congress 2022, Granada, Spain, 18–23 Sep 2022, EPSC2022-945, https://doi.org/10.5194/epsc2022-945, 2022.

Comet observation and analysis is an area where amateur observers can make a significant contribution. Their observations allow regular monitoring of comets, alerting the professional community to interesting events, and providing raw data to supplement professional data. The links between the professional and amateur communities are therefore very important.

Comet analysis is challenging. Encouraging the community to agree consistent methodologies, and parameters for analysis, will result in a more robust data set for monitoring and analysis.

The last comet workshop was held in 2015 and the comet community welcomed the opportunity to meet again.

The main aims and objectives of the workshop were agreed, following consultation, to be:

- To foster stronger working relationships and cooperation within the professional and amateur comet community, based on a shared understanding of the challenges and opportunities.

- To take stock of where cometary science stands post-Rosetta and how Pro-Am observations fit into potential future research.

- To draw together the various strands of work currently going on within the community, particularly on coordination, techniques, standards and archiving and agree the way forward.

- To consider how best to encourage, and equip, more people to become involved in the study of comets, whether directly through observation (including access to the Europlanet Telescope Network), or through analysis of online data sources.

- To explore how cometary science can be used in outreach and education.

It was also agreed that speakers should include a wide range of amateurs, students and professional astronomers, and that allowing ample time for panel-led discussions was very important. The panels should include specialists and society representatives.

An accessible location was chosen, the Stefanik Observatory in Prague, along with online access.

We will report on the outcomes from the hybrid workshop and the proposed next steps.

Acknowledgements

The workshop has been organised in cooperation with Europlanet 2024 Research Infrastructure (RI), the British Astronomical Association, Planetum Prague, and the Czech cometary community SMPH.

Europlanet 2024 RI has received funding from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under grant agreement No 871149.

How to cite: Usher, H., Snodgrass, C., Biver, N., Kargl, G., Tautvaišienė, G., James, N., Walter, F., and Černý, J.: Strengthening Pro-Am Comet Community Cooperation: Report on Europlanet Pro-Am Workshop (10-12 June 2022) , Europlanet Science Congress 2022, Granada, Spain, 18–23 Sep 2022, EPSC2022-1135, https://doi.org/10.5194/epsc2022-1135, 2022.

The technological progress of electronic, optic and mechanic domains brought high performance astronomy equipment at affordable prices for student and amateur astronomers. As a result, the amateur astronomers contribution to scientific publications has increased exponentially (e.g. Knapen 2011, Mousis et al. 2013). For example, various transient events and long term monitoring of celestial bodies can be observed with a telescope having an aperture of 0.2-0.5 m, and CCD or CMOS detector (e.g. Gherase et al. 2015).

Also, such equipment allows to attract students for a career in science and technology. The "astronomical concepts and images have universal appeal, inspiring wonder and resonating uniquely with human questions about our nature and our place in the universe" (National Academies Press, 2021). Thus, we believe that fundamental concepts related to the scientific method can be learned by a student who comes with questions related to celestial bodies, makes his own observations, processes the acquired images, analyzes the obtained data, and then presents his new findings to the community.

Motivated by these facts we developed T025 – BD4SB telescope. The acronym is represented by the aperture of the telescope (0.25 m) and the project through which we financed its acquisition (Big Data for Small Bodies). We installed this robotic telescope on the roof of the old Bucharest Astronomical Institute. This location corresponds to Minor Planet Center observatory code 073. Here we describe the setup, highlight some of the obtained results, and we discuss the perspectives.

Setup

The components of the instrument are: a Lacerta 250/1000 Newtonian telescope mounted on a Sky Watcher EQ6 Pro Go-To equatorial mount, a 14 bit QHY 294M Medium Size Cooled CMOS Camera, and a mini PC Beelink computer for controlling the setup. Including the auxiliaries (guiding telescope and camera, cables, and adapters) the cost of this setup was about 6k euros (as of 2020). Additionally, a permanent internet connection and electrical power are needed. This setup gives a field of view of 44x66 arcminutes, and a projected pixel size of 0.956 arcesc/pixel.

Fig.1 The T025 – BD4SB prepared for observations.

The full control of this instrument is made using the Nighttime Imaging 'N' Astronomy – NINA software interface (https://nighttime-imaging.eu/). The data reduction is performed using the IRAF and its PyRAF counterpart in Python. We designed a general pipeline based on Python scripts to perform the bias and flat corrections, to find the astrometric solution using Source Extractor and SCAMP software, and to retrieve the photometry of all sources in the images. All data is stored on a dedicated server and we intend to make it online available. Additionally, we use Astrometrica, Tycho, MPO Canopus and HOPS (HOlomon Photometric Software) programs for specific tasks.

The median magnitude limit is ~20 V band magnitude. Because we are observing from a light polluted area (although we are located in the Carol Park from Bucharest, and the area is surrounded by a lot of trees), the sky brightness varies between the seasons, and consequently the limiting magnitudes are in the range of 19 – 20.7. These limiting magnitudes could be obtained in about ~15 min total exposure time, and they are imposed by the brightness of the sky. The median seeing is ~2.8 arcsec, but the range of variability is 1.8 -4 arcsec.

Observations and results

The objectives of our project is to obtain high quality astrometric and photometric data which can be used for university student projects (including those for bachelor thesis and master thesis) and for participating in scientific publications. Thus, we make the following types of observations: 1) astrometric observations of asteroids and comets, prioritizing the newly discovered NEAs or those with uncertain orbits; 2) photometric observations of Solar System bodies with the aim to obtain accurate light-curves for deriving the spin-properties and their shape; 3) the occultations which are performed in various international campaigns; 4) follow-up of various exoplanets transits; 5) light-curves of variable stars.

We reported more than 100 observations to the Minor Planet Center. These include three confirmations of newly discovered NEAs, and the participation to the IAWN campaign for 2019 XS (Farnochia et al. 2022). We obtained the light-curves and rotation-periods for four NEAs, designated 4660, 153591, 12711, 2019 XS. We obtained more than 65 hours of data for asteroid (4660)Nereus which (Mansour et al. EPSC 2022).

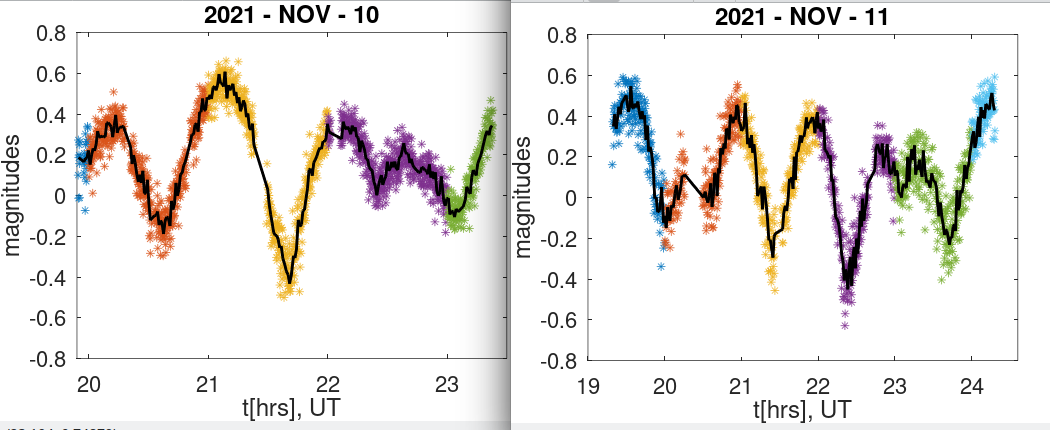

One of the challenging observation was obtained during the nights of November 10-11, 2021 for the NEA 2019 XS (absolute magnitude of 23.87). The object moved with an apparent rate of 20-30 arcsec/min, so we could use an exposure time of 5-10 sec and we had to change the field several times during the night. The result (Fig. 2) shown strong evidences that 2019 XS is a tumbling asteroid.

Fig.2 The light-curves obtained for 2019 XS. Colors correspond to different fields and the black line is a median of every 9 points.

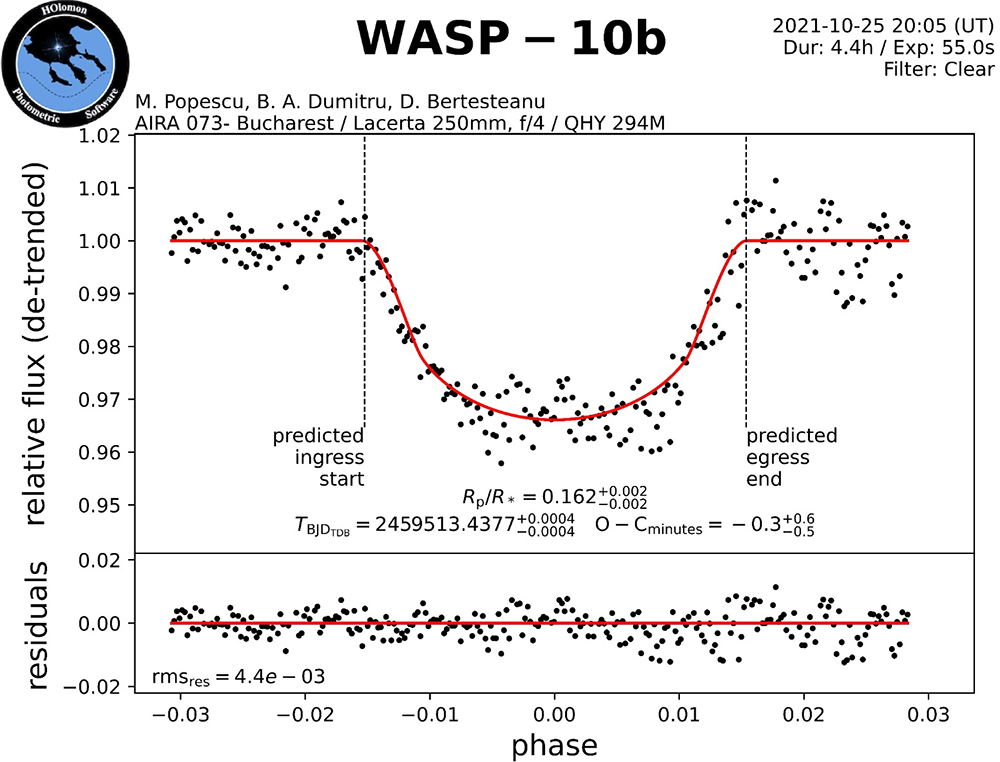

Another result we highlight is the four transits we observed for exoplanets TOI-1259Ab, WASP-10b, HAT-P-3b. The lightcurves were submitted to TRESCA-Exoplanets (http://var2.astro.cz/EN/tresca/) database. They show that such setup can obtain photometric measurements with a precision in the range of mili-magnitudes for targets as faint as 14.

Fig.3 The transit of WASP-10b exoplanet .

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by a grant of the Romanian National Authority for Scientific Research – UEFISCDI, project number PN-III-P1-1.1- TE-2019-1504, contract number TE 173/23/20/2002.

References

1. Johan H. Knapen 2011, Proceedings of ”Stellar Winds in Interaction”

2. Mousis et al. 2014, Experimental Astronomy, Volume 38, Issue 1-2, pp. 91-191

3. Radu-Mihai Gherase et al. 2015, Romanian Astronomical Journal, Vol. 25, No. 3, p.241

4. Astronomy and Astrophysics in the New Millennium; The National Academies Press. https://doi.org/10.17226/9839

5. Farnochia et al. 2022, PSJ, accepted

How to cite: Nicolae Berteșteanu, D., Popescu, M., Mihai Gherase, R., Alexandru Mansour, J., Alexandru Dumitru, B., Stanciu, B., Perrotta, A., H. Naiman, M., Blagoi, O., Dumitru, T., and Lupoae, A.: The T025 – BD4SB a pro-am collaboration for planetary sciences, Europlanet Science Congress 2022, Granada, Spain, 18–23 Sep 2022, EPSC2022-1222, https://doi.org/10.5194/epsc2022-1222, 2022.

ODAA4 | Public engagement via live online astronomy events: Sharing experiences, looking ahead

In 2009 Elisa, a student of Physics and Advanced Technologies, could not access the dome of the University of Siena Astronomical Observatory because she is forced on a wheelchair by disability. “Advanced technologies” helped her, though. Between 2010 and 2012 the Observatory instrumentation was completely updated, but, most importantly, was fully automated, and made remotely controllable trough an Internet connection.

Since 2012 the Observatory is a laboratory where university and high-school students learn to study the starry sky and how to use the most recent instruments and technologies for astronomical image acquisition and analysis. Through this acquired knowledge, small projects focused on asteroids, variable stars and extrasolar planets research can be conducted by a wide range of students, academic organizations and enthusiast citizens.

In August 2015, Sara Marullo, a student in Physics and Advanced Technologies at the University of Siena who lived very far from the observatory, managed to conduct a series of observations, required by her internship, from her home. During an asteroid study session, in a case of perfect serendipity, she discovered a peculiar binary star. A few months later, that discovery of a new double star became the topic of her thesis and of an article published in the Journal of the American Association of Variable Star Observers.

A famous Italian newspaper writes about the binary star discovered by Sara Marullo, and titles: “I discovered a star from my living room”.

Thanks to the automation implemented ten years ago, it has been possible to face the last two years of the Covid-19 pandemic without interrupting teaching, research, and scientific dissemination activities. University students were able to perform remote imaging sessions for their internships, while high school students participated remotely in astrophysics orientation projects.

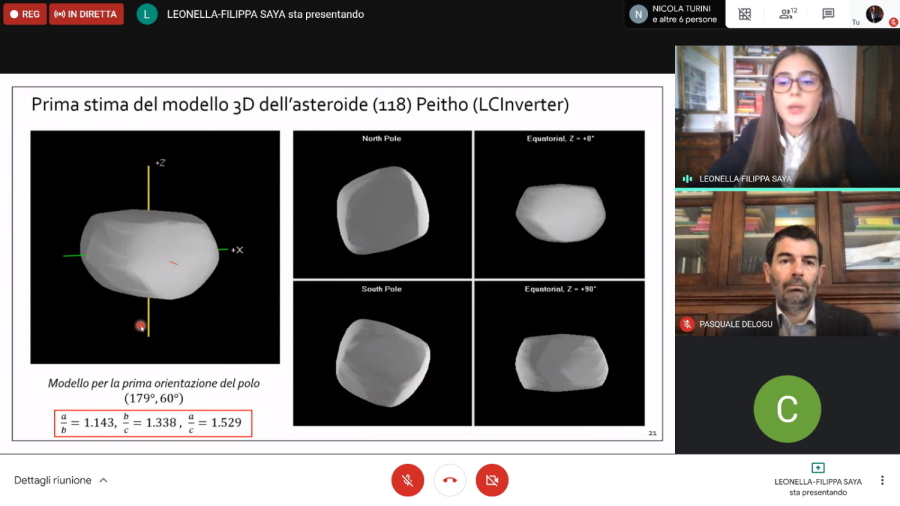

In April 2020, Leonella Filippa Saya, another student of the course in Physics, although in full pandemic lockdown, was able to finish her university internship and discuss her thesis on the photometric study and 3D modeling of the asteroid (118) Peitho. Her thesis allowed her to appear as the author of an article published in the Minor Planet Bulletin.

Leonella Filippa Saya discussing her thesis online during the pandemic lockdown.

Many high school students were able to participate remotely in the university guidance course offered by the observatory, entitled "Hunting for ancient photons, astronomy in the digital age".

An image of the Great Orion Nebula captured in February 2021 by the students of Liceo “Sarrocchi” in Siena and Liceo "Galilei" in Erba (Como) via remote operation of the telescope from their homes.

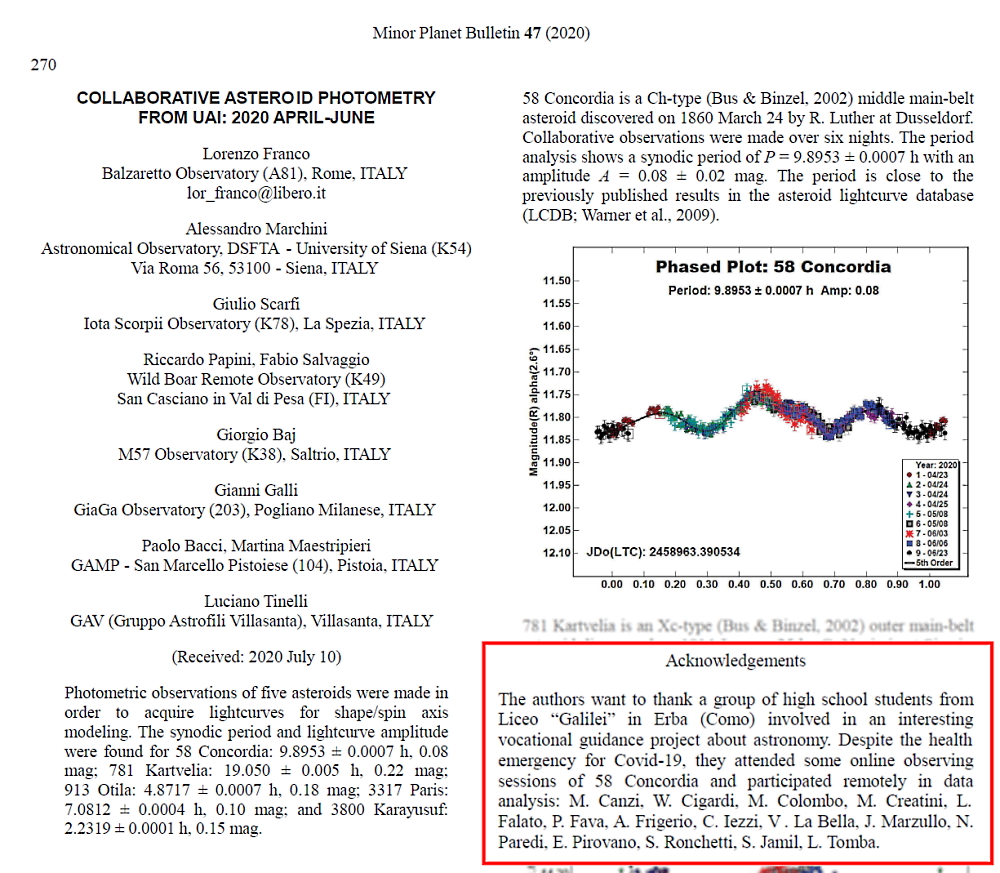

Worthy of note is a group of fifteen students from the Liceo “Galilei” in Erba (Como), in Northern Italy, who in June 2020 remotely attended some observing sessions of the asteroid (58) Concordia, and actively participated in data analysis. For their efforts, their names were mentioned in the acknowledgments on a scientific article published in the Minor Planet Bulletin.

The article published in the Minor Planet Bulletin with the acknowledgments to the students of Liceo "Galilei" in Erba (Como)

A Como newspaper writes about the guidance project in astrophysics carried out by the students of Liceo "Galilei".

During the entire lockdown period it was also possible to offer many live shows on the observatory's social profiles; these dissemination activities allowed thousands of connected citizens to follow the Observatory’s scientific research, and stimulated them to observe the starry sky from their own windows or gardens. Many of these online initiatives have been organized for particular events such as the arrival of a comet, the close passage of an asteroid, or the super-moon.

One of the most followed live shows, with over 60,000 views on YouTube and Facebook, was the one organized for the spectacular Jupiter-Saturn conjunction on December 21, 2020.

The live show carried out for the Jupiter-Saturn conjunction on December 21, 2020.

While we are fully aware of how much more engaging the physical presence of students and researchers is, since it allows greater empathy between teachers and students or between researchers and the public, the pandemic has forced the astronomical observatory to successfully continue its activities in its purest form, as an instrument: an example of how a serious problem can be transformed into an opportunity thanks to the technology developed over the years.

How to cite: Marchini, A.: An automated Astrophysics lab for everybody: the activities of the Astronomical Observatory of the University of Siena during two years of Covid-19 pandemic., Europlanet Science Congress 2022, Granada, Spain, 18–23 Sep 2022, EPSC2022-1099, https://doi.org/10.5194/epsc2022-1099, 2022.

During 2021 we started a project called Comet Chasers, to work with Primary schools in South Wales, bringing astronomy-related activities into the classroom to teach core skills.

During the period of the project (on 10 June 2021) there was a partial solar eclipse (around 22% in the area), so activities around that event were also included.

Obviously, the ideal scenario was that students would be able to view the full duration of the eclipse using a range of safe/specialist equipment, making and logging their observations for analysis later. Planned observations included using various filters (white light, CaK and Ha) to see different solar features; direct viewing through solar glasses; and indirect viewing through projection with Keplerian Sunspotters.

With a clear sky it would also be possible to use the Sunspotters for activities measuring the rotation of the Earth – with some nice maths involved.

BUT, Wales is not renowned for its good weather, particularly when something as great as a solar eclipse is happening! So backup activities were planned.

The availability of live streams from across the eclipse path was a huge advantage, so it was planned to stream those into the classroom. But just watching a solar eclipse develop over a few hours might not hold the attention of the 10-year-olds in the class, and it did not include much opportunity for learning either. So a varied programme was developed, starting with some of the science of eclipses, with appropriate hands-on activities, then using the functionality in Stellarium Web to simulate the eclipse from any location, and to view at higher speed. Students would simulate what would they be seeing if they were outside and the sky was clear. In addition, they could simulate the view from the locations of the live streams – choosing a location, changing Stellarium settings, matching the simulation with what they were seeing on the live stream and investigating what would happen next/or had just happened. It would also be a fun activity for them to simulate what maybe a relative would see from their location somewhere else….

The day before the eclipse was gloriously sunny, the day of the eclipse was…. cloudy.

But the event was still a success. To quote a student asked about what was most interesting from the Comet Chasers project: ’I found the solar eclipse most interesting when we were able to see it even though our luck was terrible because it was cloudy and rainy.’

We will present how the different activities worked in practice, more feedback from students and their teacher, and what we learnt that could be useful for other projects wishing to use mixed approaches for live events.

Acknowledgements

The Comet Chasers project was administered by Techniquest with initial funding from a Science and Technology Facilities Council SPARKS Award. Access to the telescope facilities in the Las Cumbres Observatory network is provided through the support of the Faulkes Telescope Project.

It is now delivered by a partnership of professional and amateur astronomers, the Open Uiniversity and Cardiff University, working closely with educators.

https://www.cometchasers.org/

https://www.techniquest.org/

https://www.ukri.org/councils/stfc/

https://lco.global/about/

http://www.faulkes-telescope.com/

https://stellarium-web.org/

How to cite: Usher, H. and Vaughan, S.: Using Live Feeds in the Classroom: A case study from a partial solar eclipse in cloudy Wales, Europlanet Science Congress 2022, Granada, Spain, 18–23 Sep 2022, EPSC2022-1240, https://doi.org/10.5194/epsc2022-1240, 2022.

What are the notable forthcoming astronomical events for “the person in the street”? We present a brief overview of notable eclipses, appulses, and other groupings involving the Moon and the naked-eye planets. We’ll also make use of some of our other databases to answer questions such as: what is the biggest solar eclipse in terms of population coverage?

How to cite: Jones, G.: Coming soon to a sky near you: notable naked-eye astronomical events 2022–2040, Europlanet Science Congress 2022, Granada, Spain, 18–23 Sep 2022, EPSC2022-1253, https://doi.org/10.5194/epsc2022-1253, 2022.

ODAA5 | Tools, resources and opportunities for education initiatives in planetary science and astronomy

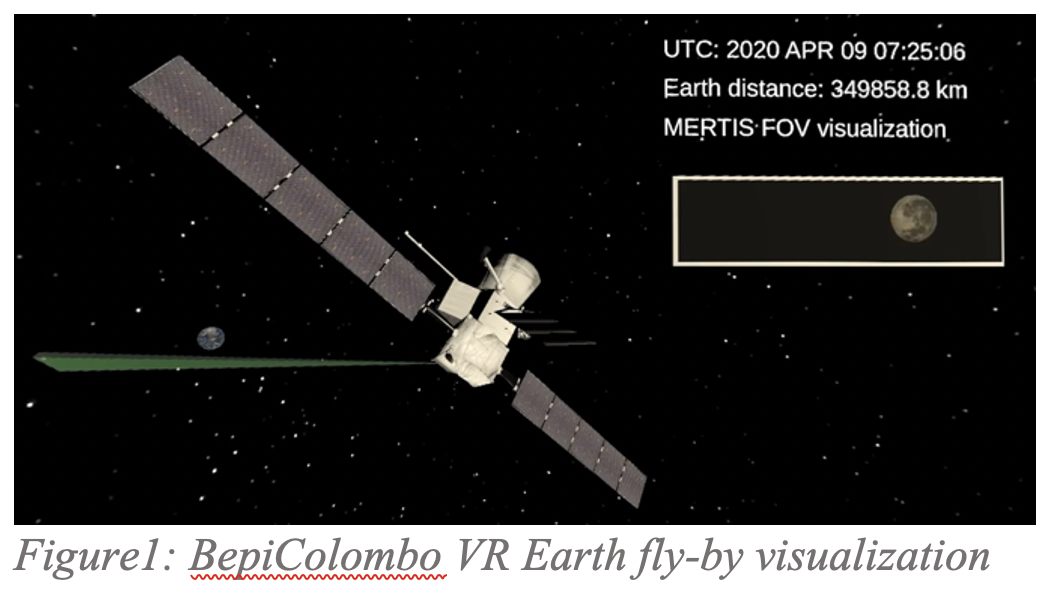

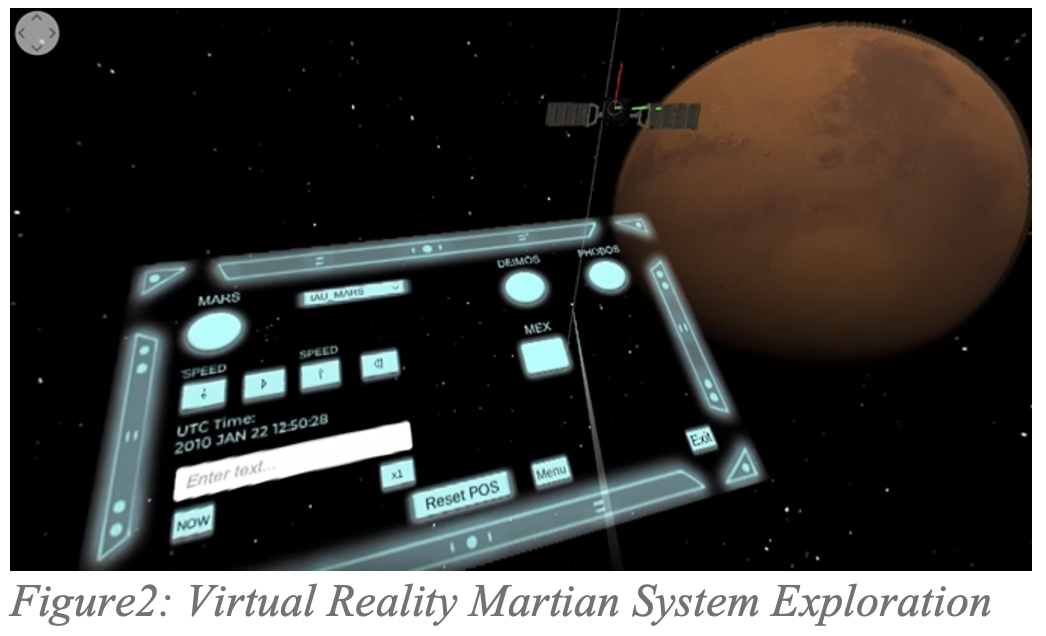

Introduction: The ESA SPICE Service (ESS) based at the European Space and Astronomy Center (EASC) provides ESAs Solar System Exploration missions ancillary data and geometry information to the science community and to the science ground segments in the shape of SPICE data. Most of this data is three-dimensional, and its interpretation and visualization is one of the challenges faced by the ground segments that operate the spacecrafts and the scientists that study its data. Science Observations and contextual Data analysis of Planetary missions can be naturally accommodated into 3D visualizations. Virtual Reality (VR) brings an unprecedented level of interaction possible with these visualizations, and emerging VR platforms such as Oculus VR, Google Cardboard or Samsung Gear VR are making these technologies accessible to the wide public. VR might become in the near future, not only a tool for outreach and data visualization, but also a key part for spacecraft science operators, becoming a key element of the ground segments.

The ESA SPICE Service: The ESA SPICE Service (ESS) leads the SPICE operations for ESA missions. The group generates the SPICE Kernel Datasets (SKDs) for missions in development (JUICE, ExoMars 2022, Hera, Comet-Interceptor, and EnVision), missions in operations (Mars Express, ExoMars 2016, BepiColombo, and Solar Orbiter) and legacy missions (Venus Express, Rosetta and SMART-1). ESS is also responsible for the generation of SPICE Kernels for INTEGRAL. Moreover, ESS provides SPICE support Kernels for Gaia and James Webb Space Telescope. ESS also provides tools for the exploitation of the SPICE Kernels, consultancy and support to the Science Ground Segments of the planetary missions, the Instrument Teams and the science community. The access point for the ESS activities, data and latest news can be found at the following site https://www.cosmos.esa.int/web/spice. ESS works in partnership with NAIF.

Virtual Reality Applications: Examples of applications of these technologies in operations are already available: the Mars rovers, especially Curiosity have embraced VR and Augmented Reality techniques (some applications are publicly available such as (Access Mars). New mission concepts such as recently selected Dragonfly (a NASA rotorcraft lander for Titan) have already started to develop operation concepts based on VR. Another example of a successful VR application is ESASky [2]. ESASky is a science driven discovery portal developed at ESAC providing full access to the entire sky as observed with Space astronomy missions that has VR extensions and capabilities.

VR for Solar System Exploration: This contribution aims to describe the first steps of delivering advanced functionalities for VR tools created to access Solar System geometry, with particular emphasis on visualization of the science observations carried out by the ESA Planetary fleet on the Solar System (Mars Express, ExoMars2016, BepiColombo, Solar-Orbiter, Rosetta, SMART-1, JUICE, etc.). The functionalities will also include advanced functionalities for navigation and data selection in a VR space through peripherals like Oculus Touch.

References: [1] Acton C. (1996) Planet. And Space Sci., 44, 65-70. [2] Merin, B. et al., (2015) ESA Sky: a new Astronomy Multi-Mission Interface.

How to cite: Escalante Lopez, A., Valles, R., and Arviset, C.: Solar System Exploration with Virtual Reality, Europlanet Science Congress 2022, Granada, Spain, 18–23 Sep 2022, EPSC2022-9, https://doi.org/10.5194/epsc2022-9, 2022.

Introducing a presentation about the landing sites of Mars landers, and the places on Earth having corresponding coordinates. The presentation is free to use for education and outreach purposes under Creative Commons BY-NC-ND 4.0 license.

How to cite: Kahanpää, H.: Where on Earth are the Mars landers?, Europlanet Science Congress 2022, Granada, Spain, 18–23 Sep 2022, EPSC2022-81, https://doi.org/10.5194/epsc2022-81, 2022.

We will present the opportunities of an ERASMUS+ strategic partnership KA2 funding schemes which we used to support (not only) early career researchers in astronomy. ERASMUS+ is a general funding scheme and we describe here one particular project funding education and international partnerhsip of institutions in astronomical research. Our first Erasmus program (2017-2020) was enabling mobilities of early career researchers between Spanish, Czech and Slovak institutes. The mobilities helped young researchers to gain experience with the modern instrumentation at Observatorio Roque de Los Muchachos at La Palma, Spain. Our program helped several young researchers to obtain tenure track position in astronomical research. We also obtained a continuation of the ERASMUS+ program for another period (2020-2023) which focuses on the development of careers of young researchers and helping them to become future faculty leaders. Furthermore, within the program we performed educational activites for children of various ages. This contribution will describe our programs and its aims and results. We will also share our experience with the application process and with the ERASMUS+ program itself. We will describe the opportunities the ERASMUS+ program is offering for the education in an astronomical research for non-university research institutions.