Abstracts with displays

TP1 | Mercury Science and Exploration

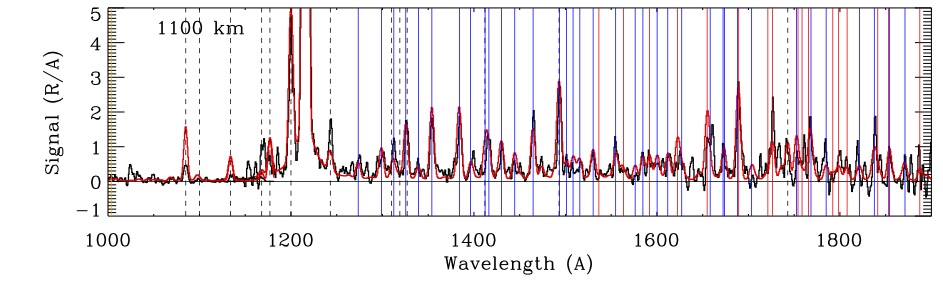

The discrete photoemission properties of atomic and molecular species stimulated by solar radiation are an important tool for quantitative work with remote sensing experiments. In an optically thin atmosphere, the total column amount of a given species is given in terms of a solar-forced g-value, defined as an emission probability per atom (photon s−1atom−1). For an optically thin gas and a measured emission brightness (4πI), the column abundance N is obtained through the relation 4πI= gN. Discrete emission lines and Fraunhofer features in the solar spectrum are responsible for a strong dependence of the g-values on Doppler velocity for many species. Because of Mercury’s eccentric orbit, some g-values can vary by over an order of magnitude during the orbital period. In addition, g-values are dependent on the instantaneous heliocentric radial velocity, which varies as an atom is ejected from the surface and moves through gravitational and radiation pressure accelerations. Thus knowledge of how the g-values vary is critical to interpretation of spectroscopic data. In previous work, g-values were calculated for 12 species that were to be targeted by MESSENGER. The species of interest included sodium, potassium, and calcium, which had been observed in Mercury’s exosphere through ground-based observations pre-MESSENGER, and hydrogen and oxygen, measured (or potentially only an upper limit in the case of O) by the UV spectrometer experiment on the Mariner 10 spacecraft. In addition, sulfur, magnesium, carbon, Ca+ and Mg+ are observable by Bepi-Colombo as well as MESSENGER. Helium EUV emission at 584 Å, not within the MESSENGER UVVS wavelength range, will be observable with the Bepi-Colombo UV spectrometer. Of particular importance for Mercury is the dependence of the g-values on the bulk motion of the gas relative to the Sun. This heliocentric relative velocity is often quite large due to the high initial velocity of the ejected atoms and the subsequent radiation pressure acceleration.

- Motivation

Mercury’s orbit is highly elliptical, having an ellipticity of 0.2. This results in a variation of the heliospheric relative velocity varying by ± 10 km/s. The g-values published by Killen et al. (2009) were therefore calculated for Doppler shifts of this magnitude. However, it has become apparent that the heliocentric relative velocity of atoms in Mercury’s exosphere varies considerably more than the velocity at rest with respect to the planet, both due to the initial ejection velocity and due to radiation pressure, that is especially strong for Na. The velocity of Ca atoms is also extreme, due to as yet unknown processes, but possibly due to dissociation of a Ca-bearing molecule. We have therefore extended the g-values to ±50 km/s relative to their at-rest values. The g-values have been scaled using the solar spectrum originally used by Killen et al. (2009) (e.g. Hall and Anderson, 1991) and available in the appendix to that paper. In addition, for the Mg line at 285.296 nm, we used the TSIS-1 solar spectrum available from the LISIRD website (https://lasp.colorado.edu/lisird/). In March 2022, the TSIS-1 HSRS was recommended as the new solar irradiance reference spectrum by the Committee on Earth Observation Satellites (CEOS) Working Group on Calibration and Validation (WGCV). TSIS-1 HSRS is developed by applying a modified spectral ratio method to normalize very high spectral resolution solar line data to the absolute irradiance scale of the TSIS-1 Spectral Irradiance Monitor (SIM) and the cubesat Compact SIM (CSIM). The spectral resolution of this spectrum is 0.25 nm. The high spectral resolution solar line data from the Air Force Geophysical Laboratory ultraviolet solar irradiance balloon observations, used in the Killen et al. (2009) work, have a spectral resolution of 0.015 nm. The g-values calculated herein at high resolution must be convolved to the spectral resolution of the instrument used for the observations to be analyzed. The UVVS spectrometer on MESSENGER was a scanning grating monochromator that covered the wavelength range 1150 - 6100 Å with an average 6 Å spectral resolution (McClintock & Lanton 2007). The Bepi Colombo UV spectrometer, PHEBUS, is a double spectrometer for the Extreme Ultraviolet range (550 - 1550 Å) and the Far Ultraviolet range (1450 - 3150 Å) using two micro-channel plate (MCP) detectors with spectral resolution of 10 Å for the EUV range and 15 Å for the FUV range (Chassefiere et al. 2008).

We show plots of extended g-values for Na (D1), K (D1 & D2), Ca, and Mg. The Mg g-values are given for both the Hall and Anderson (1991) solar spectrum and for the TSIS-1 spectrum for comparison of high and low-resolution results.

Figure 1. The g-value for Na (D1) at 589.756 nm in vacuum continues to increase as the Doppler shift increases. The D2 line g-values similarly increase beyond a velocity of ±10 km/s to ± 50 km/s. Therefore the column abundance for high velocity atoms will be over-estimated using the formerly published g-values. This is especially important for estimates of escape.

Figure 2. G-values for the Ca 422.7 nm line calculated to ±50 km/s. In the case of the Ca line, the g-value continues to increase for heliocentric relative velocity > 25 km/s, but decreases for heliocentric relative velocities < -35 km/s. As for Na, the Ca column abundance anti-sunward of Mercury will be overestimated using the previously published g-values.

Figure 3. The extended g-values for the K (D2) line at 404.53 nm (green) and K (D1) 404.84 nm (vacuum wavelengths) at 0.352 AU are quite complex owing to the underlying solar spectrum. Care must be taken to calculate the column abundance at the instantaneous heliocentric relative velocity of the atom.

Figure 4. The g-value for the Mg 285.296 nm line is also quite complex. This figure shows the g-value calculated using the high resolution of the Hall and Anderson (1991) solar spectrum at a spectral resolution of 15 mÅ.

Figure 5. The g-value for the Mg 285.296 nm line using the low resolution TSIS-1 spectrum at 0.25 Å resolution shows little high frequency variation, as expected.

How to cite: Killen, R., Vervack, R., and Burger, M.: Variation of g-values of major species with heliocentric velocity, Europlanet Science Congress 2022, Granada, Spain, 18–23 Sep 2022, EPSC2022-53, https://doi.org/10.5194/epsc2022-53, 2022.

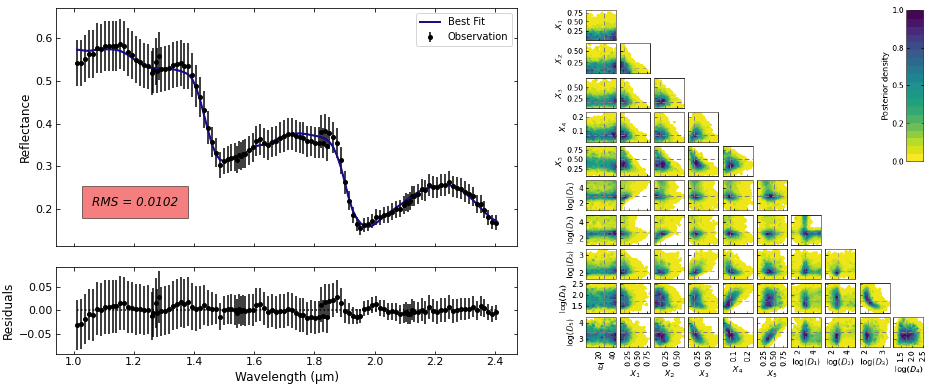

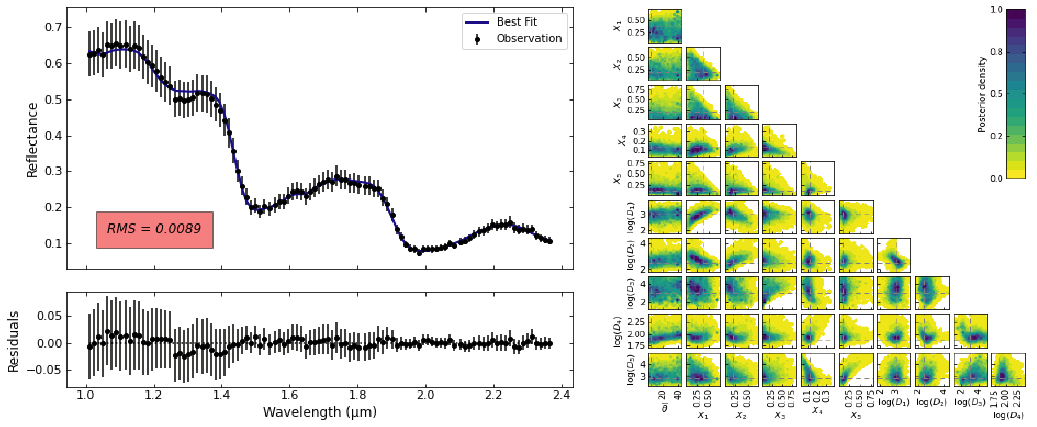

In this work, we apply a method previously discussed in [1] to assess the presence of water ice in Mercury’s Polar Shadowed Regions (PSR) mixed to S-rich volatile species like SO2, H2S, and volatile organics, intending to verify their detectability from Bepi Colombo’s orbit and to optimize SIMBIO-SYS/VIHI observations. PSR icy deposits located within the floor of the Kandinsky crater are simulated in terms of I/F spectra corresponding to mixtures of H2O-H2S and H2O-SO2 with grain sizes of 10, 100, and 1000 µm as resulting from indirect illumination by the scattered solar light coming from the crater’s rim. The spectral simulations, performed following the method described in [2], and including the ice-regolith mixing (areal or intimate) as modeled in [3], allow for exploring different volatile species abundances and grain size distribution.

The resulting ice detection threshold are evaluated by means of the computation of VIHI’s instrumental signal-to-noise ratio as given by the instrumental radiometric model [4]. In this way, a synergistic use of illumination models, spectral simulations and resulting SNR calculations will help us to optimize the VIHI’s observation strategy across Mercury’s polar regions with the aim to detect, identify and map volatile species. This task is one of the primary scientific goals of the 0.4-2.0 µm Visible and Infrared Hyperspectral Imager (VIHI) [5], one of the three optical channels of the SIMBIO-SYS experiment [6] on ESA’s BepiColombo mission.

Due to orbital characteristics and proximity to the Sun, Mercury’s polar regions undergo large variations in illumination conditions during the hermean year [1]. At poles, Permanent Shadowed Regions (PSRs) occur on deep craters and rough morphology terrains that are not directly illuminated by the Sun during the hermean day. Nevertheless, some of these areas could experience partial illumination caused by multiple scattered light coming from nearby illuminated areas. Despite the orbital vicinity to the Sun, Mercury’s PSRs can maintain cryogenic temperatures across geological timescales resulting in the condensation and accumulation of volatile species [7]. While water ice is the more certain species in Mercury’s PSR, it is not precluded the occurrence of other secondary species rich in sulfur or even organic matter.

In fact, the total surface area of PSRs between latitudes 80−90° south is not negligible, being estimated at about 25.000 km2 [8], about two times larger than the same geographic area on the North Pole [9].

References: [1] Filacchione G. et al., MNRAS, 498, 1308-1318, 2020. [2] Raponi A. et al., Sci. Adv., 4, eaao3757, 2018. [3] Ciarniello. M. et al., Icarus, 214, 541, 2011. [4] Filacchione G. et al., Rev. Sci. Instrum., 88, 094502, 2017. [5] Capaccioni F. et al., IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens., 48, 3932, 2010. [6] Cremonese G. et al., Space Sci. Rev., 216, 75, 2020. [7] Paige D. A. et al., Science, 339, 300, 2013. [8] Chabot N. L. et al., J. Geophys. Res., 123, 666, 2018. [9] Deutsch A. N. et al., Icarus, 280, 158, 2016.

Acknowledgments: We gratefully acknowledge funding from the Italian Space Agency (ASI) under ASI-INAF agreement 2017- 47-H.0.

How to cite: Filacchione, G., Raponi, A., Ciarniello, M., Capaccioni, F., Frigeri, A., Galiano, A., De Sanctis, M. C., Formisano, M., Galluzzi, V., and Cremonese, G.: DETECTION OF ICY SPECIES IN MERCURY’S PSRs: SPECTRAL SIMULATIONS FOR SIMBIO-SYS/VIHI ON BEPI COLOMBO, Europlanet Science Congress 2022, Granada, Spain, 18–23 Sep 2022, EPSC2022-191, https://doi.org/10.5194/epsc2022-191, 2022.

Strofio is a mass spectrometer, aboard the BepiColombo mission, that utilizes a time-of-flight method to determine the mass-per-charge of each particle entering its aperture in order to study the chemical composition of the exosphere of Mercury. Optimization of Strofio involves finding a balance between system efficiency and mass resolution while increasing the signal-to-noise ratio. In order to ensure our data is exospheric in nature, we must separate the Mercury environment from the background environment. The background environment is made up of thermal particles produced from sources like the outgassing of the spacecraft as well as from the instrument itself. This problem can be addressed by assigning the correct voltages to the source apparatus, thereby realizing a background filter. This filter works best in Mach 2 or larger regimes to ensure the targeted particles do not get filtered out with the background. My work focuses on writing and running a series of computer simulations that optimize the velocity filter in accordance with the configuration of the flight model.

How to cite: Schroeder, J., Livi, S., Allegrini, F., and Wurz, P.: Increasing the Signal-to-Noise Ratio of a Mass Spectrometer Using a Velocity Filter, Europlanet Science Congress 2022, Granada, Spain, 18–23 Sep 2022, EPSC2022-368, https://doi.org/10.5194/epsc2022-368, 2022.

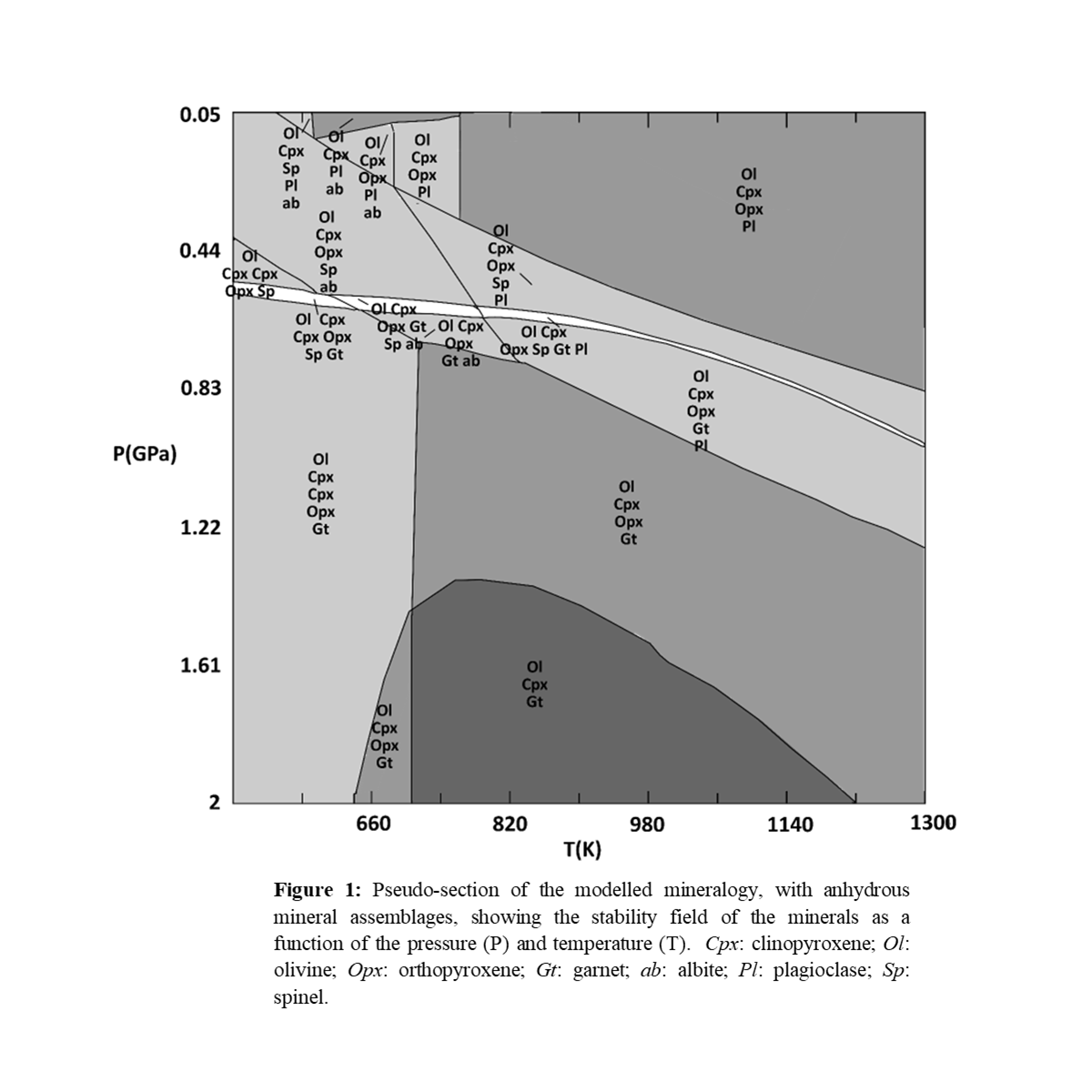

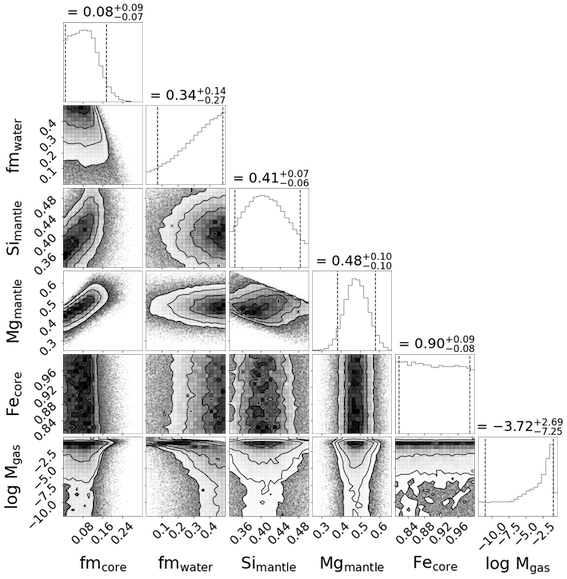

Mercury possesses the second, highest density (5.23 g/cm3) in the Solar System after Earth. This high density is likely the result of the presence of a large inner core, composed of iron-light elemental alloys, overlayed by a relatively thin silicate shell, comprising the crust and the mantle [1]. The mercurian crust has been analyzed by the Messenger spectroscopic suite of instruments, which included, among others, the XRS (X-ray Spectrometer) and GRS (Gamma-Ray Spectrometer) spectrometers, capable of detecting the elements present on Mercury’s surface. The surface mineralogy of Mercury is dominated by enstatite and plagioclase, with small amounts of sulfides (oldhamite, CaS), the presence of which is a strong clue of the extremely reducing conditions which have led to Mercury’s accretion and differentiation [2]. The mercurian crust has been found to be very thin with estimates ranging between 26 ± 11 km and 35 ± 18 km [3,4]. Moreover, the mercurian mantle is also thin, thinner than other terrestrial planets' mantles, with an estimated thickness between 300 km – 500 km [5]. In addition, the mantle shows a great lateral heterogeneity in mineral compositions, as indicated by the local, abrupt chemical changes in crustal chemistry [6].

Mercury’s large metallic core, likely partially molten and making up to 42% of its volume, combined with surficial observations (which have revealed a very small FeO concentration), and the peculiar position occupied by Mercury in the solar nebula, lead us to hypothesize a very reduced geochemical environment as its birthplace [7]. In literature, chondrites belonging to CB and enstatite chondrites (EN) have been considered the best precursor materials for Mercury’s composition [6, 8, 9, 10], sharing many analogies both in geochemistry and thermal evolution.

In light of the above, we chose a CB-like bulk composition to model the mineral assemblage of the mercurian mantle.

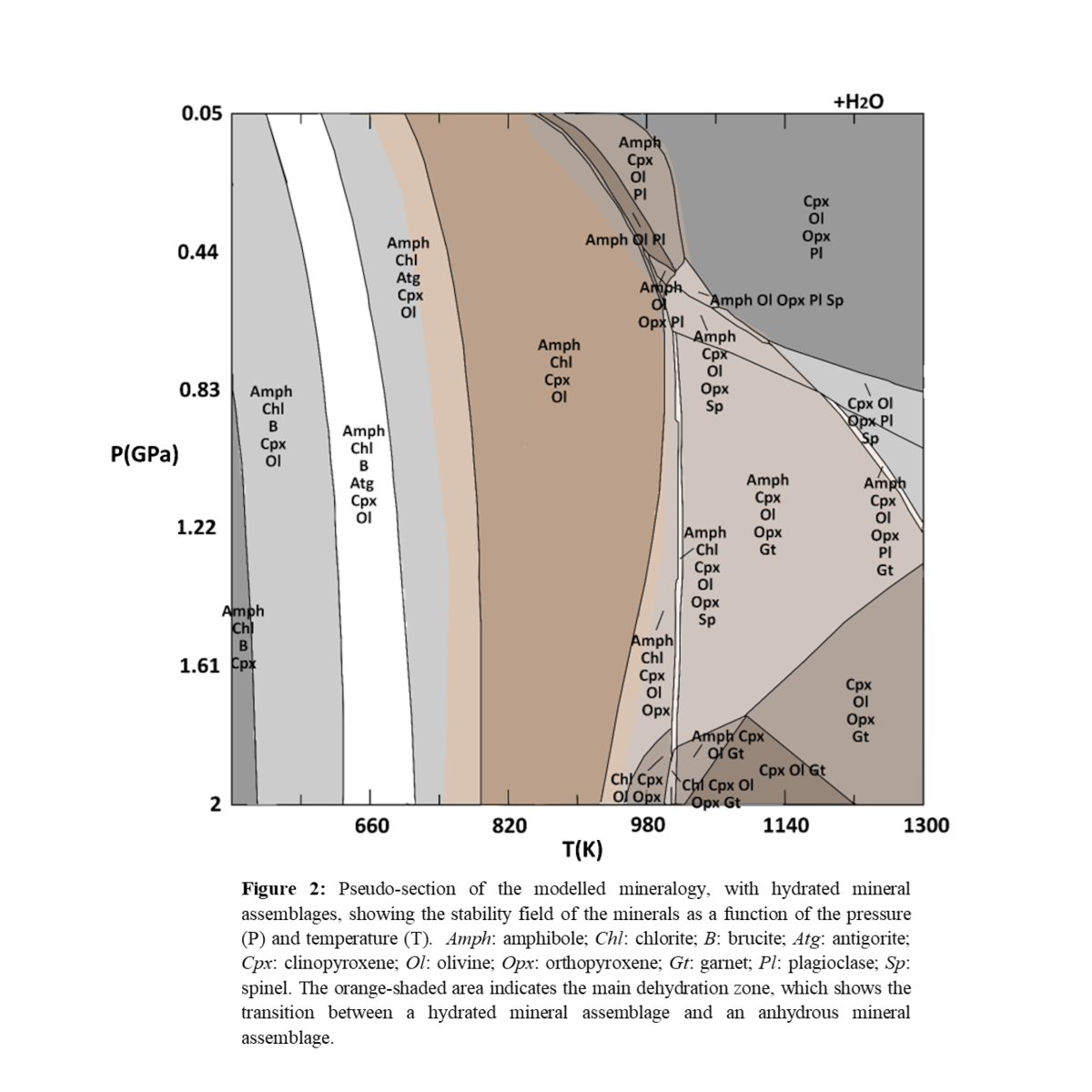

We reconstruct the evolution of the mercurian mantle starting from a CB chondrite-like bulk silicate composition, at thermodynamic equilibrium, as a function of temperatures and pressures estimated for Mercury’s mantle employing the Perple_X algorithm (6.9.1 version) [11]. We describe a dry scenario because the water abundance estimated for the bulk composition of Mercury silicate shells is quite low (0.3wt%, [12]) and due to the high-temperature ranges included in the model.

We predict that the peculiar geochemical environment where Mercury may have originated is characterized by a very low oxygen fugacity, which would result in a very reduced mineral assemblage for the mantle, dominated by pyroxenes and silica polymorphs, as shown in [9]. We expect that significant mantle phase transitions are unlikely due to the relative thinness of the mantle and the consequent low-pressure ranges (always <10 GPa) [13].

In conclusion, contrary to the terrestrial mantle, olivine is not predicted to be stable in our model. In effect, the low fO2 results in stabilizing pyroxenes relative to olivine [9], producing mineral assemblages quite different from terrestrial peridotites.

Acknowledgments

G.M. and C.C. acknowledge support from the Italian Space Agency (2017-40-H.1-2020).

References

[1] Solomon, S. C., et al., (2018). Mercury: The view after MESSENGER (Vol. 21). Cambridge University Press. [2] Weider, S. Z., et al., (2012)., J. Geophys. Res. Planets, 117(E12).[3] Sori, M. M. (2018). Earth & Planet. Sci. Lett., 489, 92-99. [4] Padovan, S., et al., (2015). Geophys. Res. Lett., 42(4), 1029-1038. [5] Tosi P. et al. (2013), J. Geophys. Res. Planets, 118(12), 2474-2487.[6] Charlier, B. et al., (2013). Earth & Planet. Sci. Lett., 363, 50-60. [7] Cartier, C., and Wood, B. J. (2019). Elements,15(1), 39-45. [8] Stockstill‐Cahill, K. R., et al., (2012). J. Geophys. Res. Planets, 117(E12). [9] Malavergne, V. et al., (2010). Icarus, 206(1), 199-209. [10] Zolotov, M. Y., et al., (2013). J. Geophys. Res. Planets, 118(1), 138- 146. [11] Connolly, J. A. (2005). Earth & Planet. Sci. Lett., 236(1-2), 524-541. [12] Vander Kaaden, K. E., & McCubbin, F. M. (2015). J. Geophys. Res. Planets, 120(2), 195-209. [13] Riner M. A.,et al., (2008). J. Geophys. Res. Planets, 113(E8).

How to cite: Cioria, C. and Mitri, G.: Mineralogical model of the mantle of Mercury, Europlanet Science Congress 2022, Granada, Spain, 18–23 Sep 2022, EPSC2022-432, https://doi.org/10.5194/epsc2022-432, 2022.

Introduction

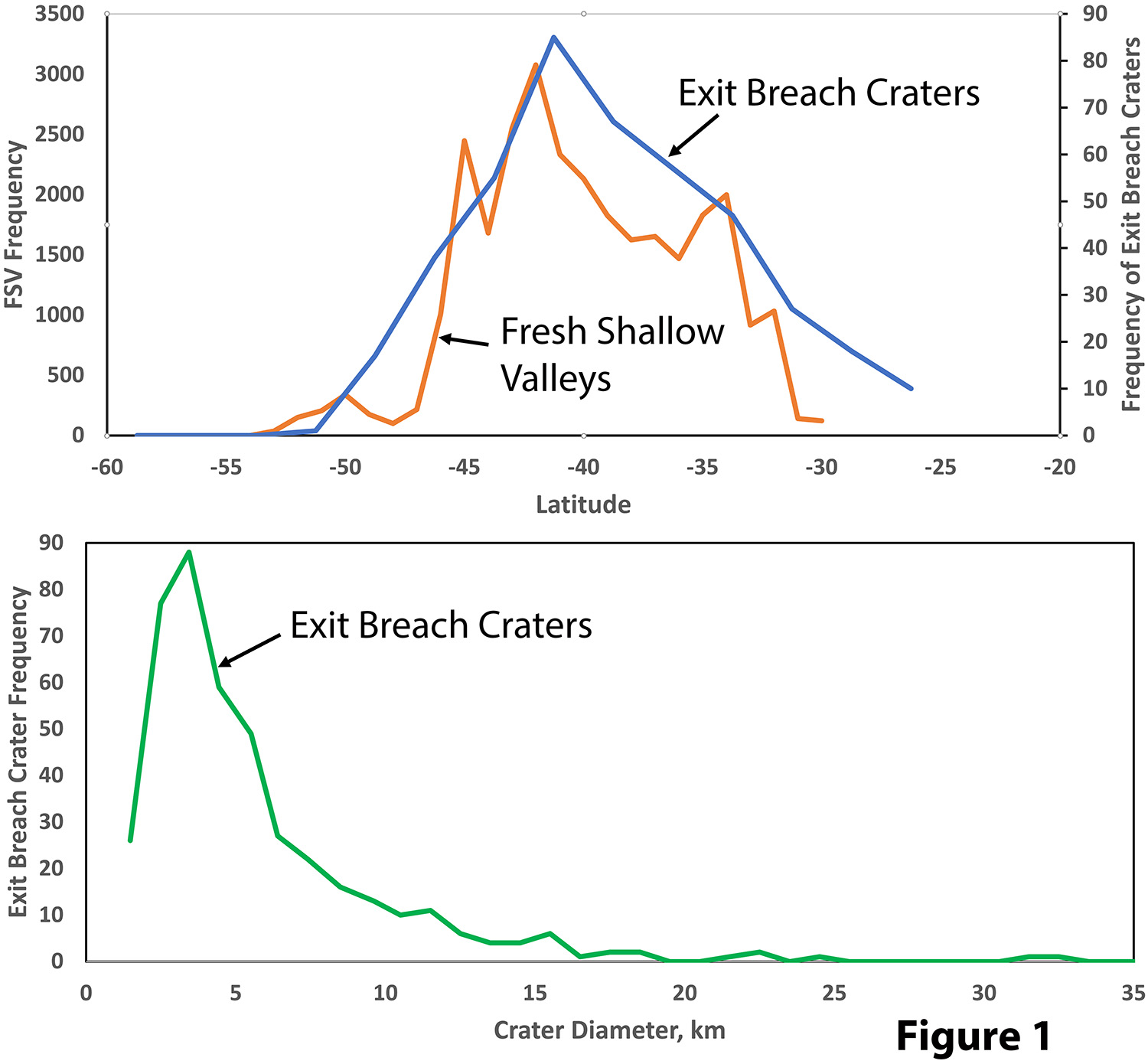

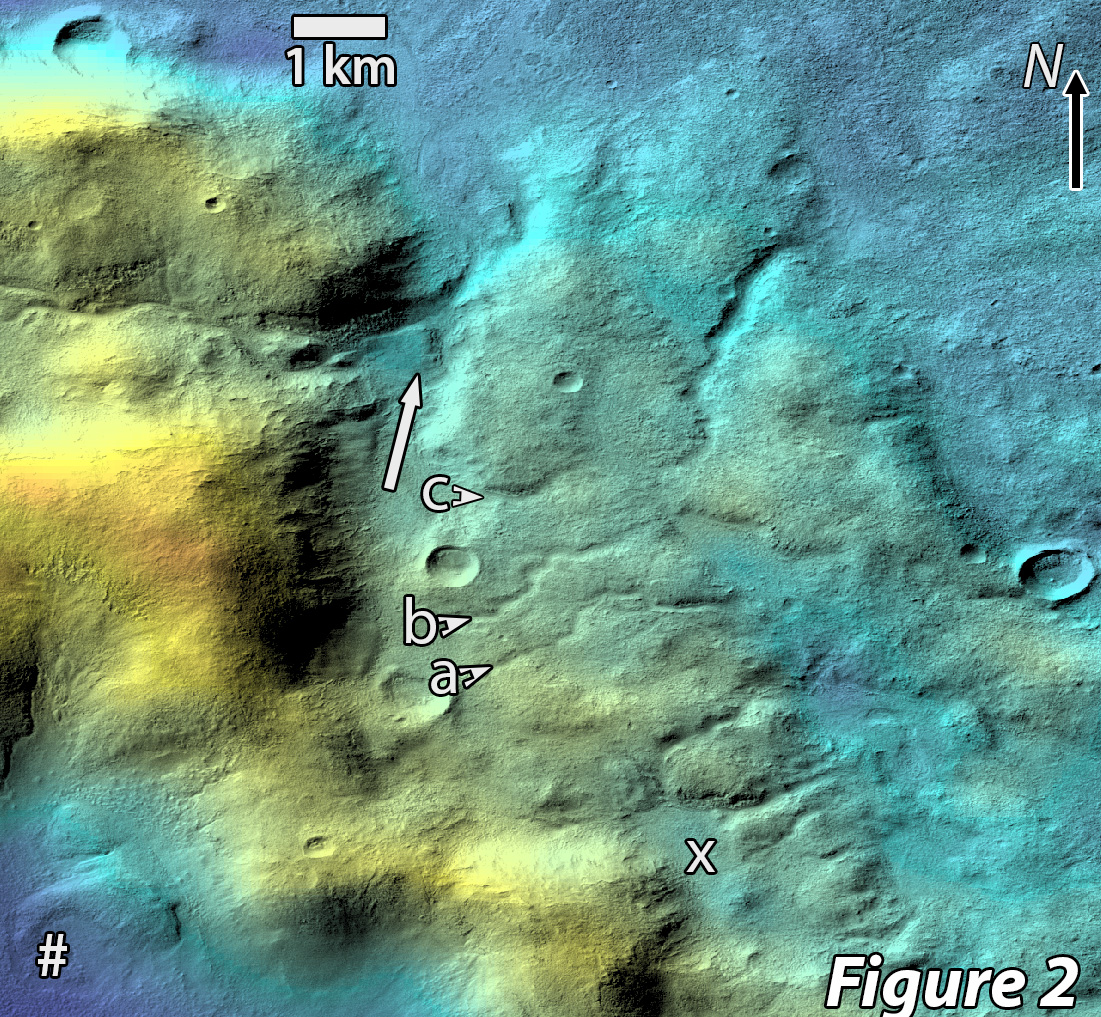

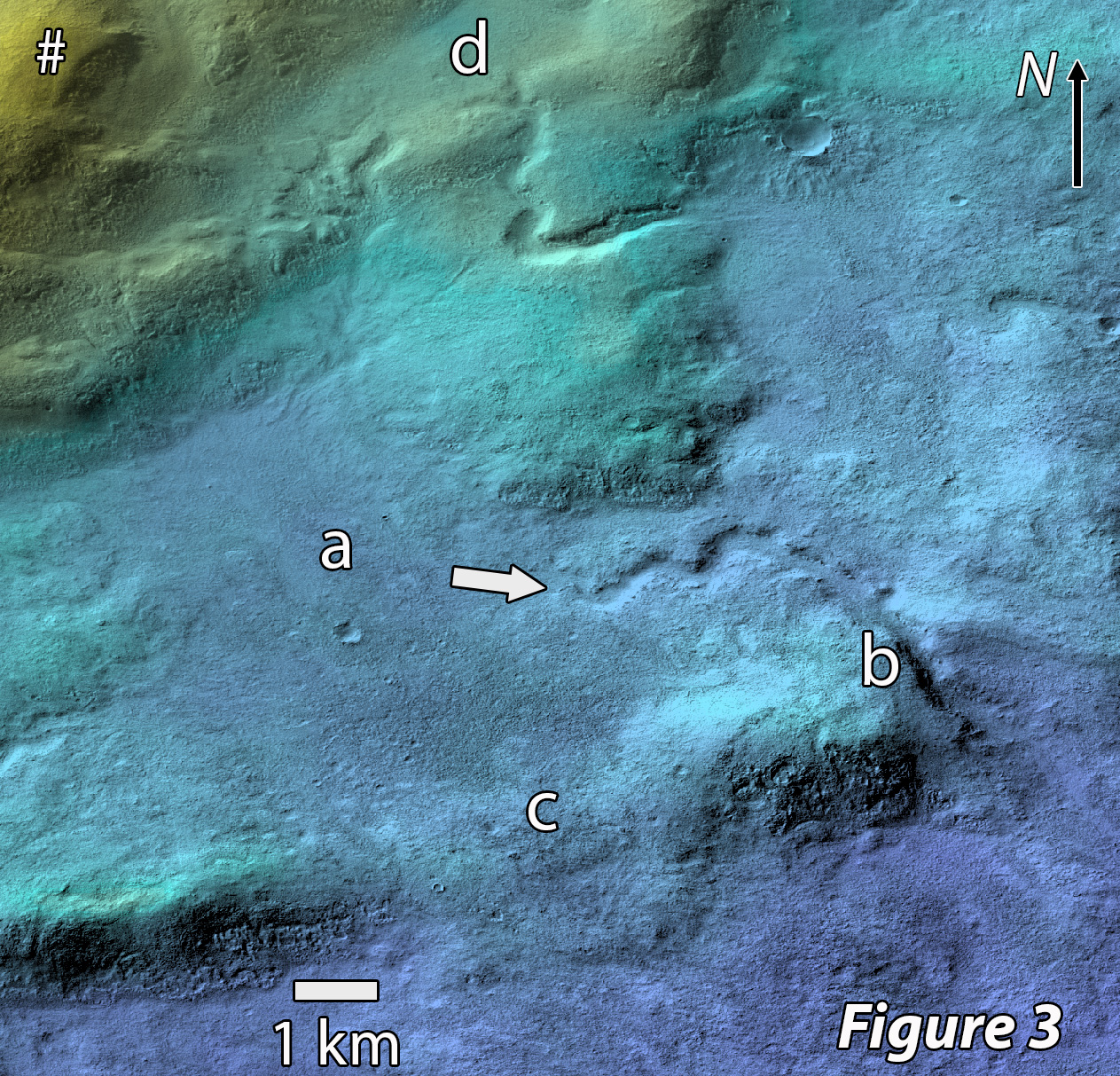

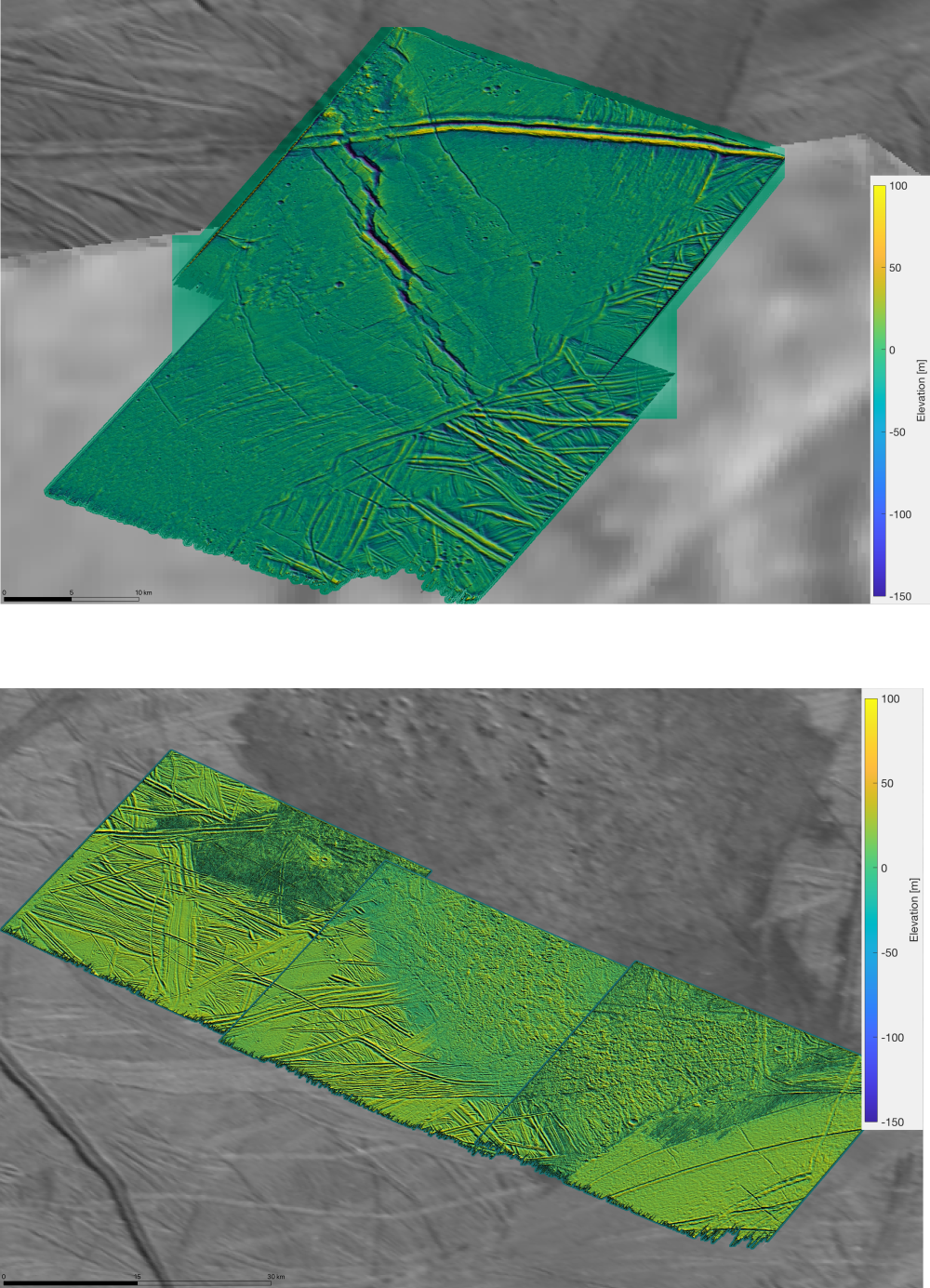

Mercury’s surface is characterized by large and well-preserved impact basis. They represent important records regarding the magnitude and timing of the “Late Heavy Bombardment” in the early inner solar system. It has been suggested that Mercury and Moon had the same early impactor population based on their similar crater size frequency distributions [1,2]. In this study we investigated the basins using complementary topography and gravity data sets derived by MESSENGER [3,4]. Gravitational data in combination with the surface morphology of the basins may help improve our understanding of their formation processes and alterations with time. Gravity anomalies hint at complex interior structures, such as mass and density distributions in the upper crust of the planet, which is beneficial for identifying highly degraded or buried basins.

In this study, we present an inventory of basins larger than 150 km, for which we introduce a classification scheme according to morphological and gravitational signatures.

Methods and data sets

The topographic digital terrain model (DTM) used in this study was derived by the Mercury Dual Imaging System (MDIS), involving a narrow-angle- as well as a wide-angle camera [3]. Gravity data data of the MESSENGER spacecraft, which resulted in a gravity field model with a resolution of degree and order 160, equivalent to approximately 28 km in the spatial domain [4].

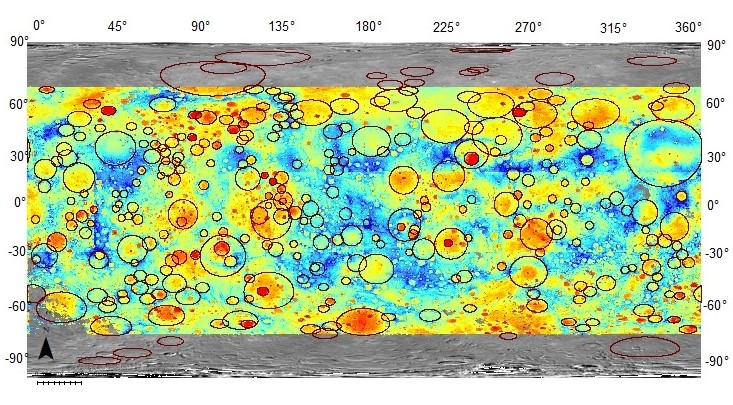

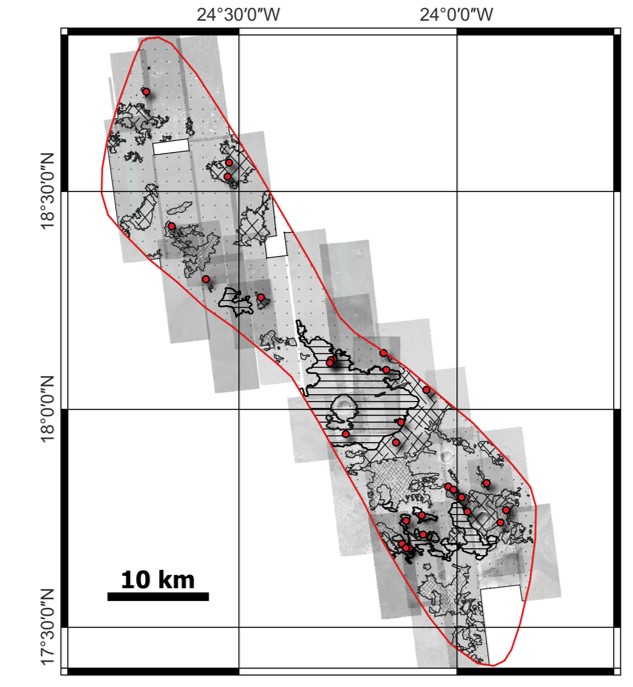

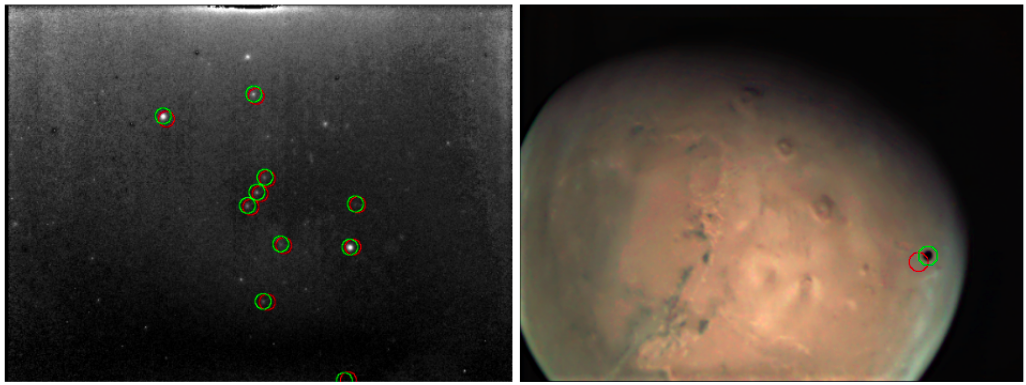

Fig 1: DTM of Mercury’s topography. Circles mark the identified basins.

Results

Our preliminary basin inventory hosts 311 basins (Fig.1). A clear correlation is noticed between the topography and gravity data, in particular impact basins are well detectable in both data sets. Their global distribution is non-uniform. Around 60% of basins are located on the western hemisphere. This asymmetric pattern may be caused by (I) lateral thermal variances of the crust [1], (II) synchronous spin- and orbital periods of the planet in its early history, which later changed to its presently observed 3:2 spin-orbit resonance [2], (III) resurfacing events that includes the northern smooth plains and following flooding of existing basins on the eastern hemisphere, which would eventually bury smaller complex basins.

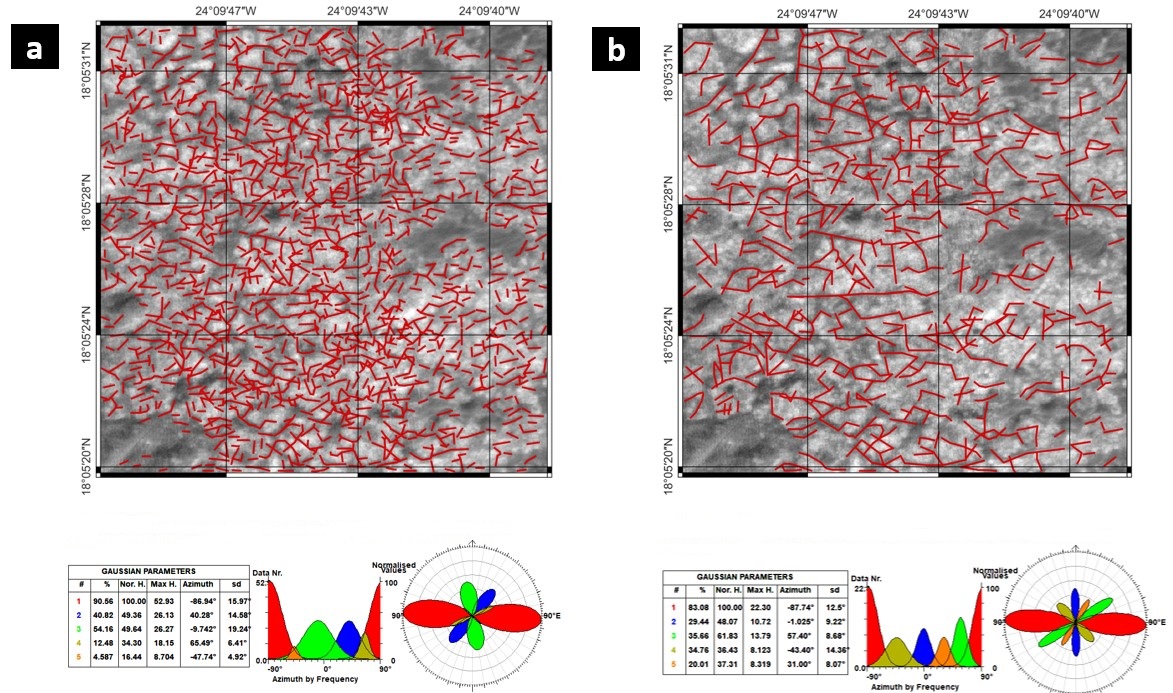

With increasing diameter basins were found to show more complex gravity- and topography signatures. Basins with smaller diameter (<160 km) display a central peak. With increasing size, the morphology changes to a peak ring in the center. The transition from peak ring to multi-ring basins is suggested to occur at 350 km as is attested by a distinct change in the gravitational signal. The gravity disturbance remains mostly in strong negative values. This value shifts to a positive one for basins larger than 350 km.

High positive gravity signals were also recognized in the Bouguer anomaly map. Some basins (>350 km) possess a positive Bouguer anomaly in the basin center surrounded by a negative anomaly annulus (bullseye pattern) (Fig 2). Gravity data are reflecting mass/density deficits and excesses in the planet’s subsurface structures. The high mass and density concentrations may be caused by an uplift of mantle material after the crater excavation phase [5]. The excavation was followed by an isostatic adjustment caused by cooling and contraction of the melt pool. Subsequently, crust is expected to be thinner.

Fig 2: Left: Profile of Bouguer anomaly, Right: Bouguer anomaly map; showing positive strong anomaly in center surrounded by negative annulus.

However, basins with small diameter (<200 km) were found to show strong positive anomalies as well, that indicate a mantle uplift after their formations. Due to limited data resolution (particularly in the south) the localization and accuracy of the Bouguer anomalies is not certain.

Other 208 basins where identified, but could not be characterized in detail due to their high degradation state (rim <50%). Most of these are filled by secondary material. Future data with improved resolution would be required to verify these results.

We investigated the amplitude of Bouguer anomalies in the basin centers and surroundings as a measure of crustal thinning, which may hint at basin relaxation state. Lunar observations showed, that young basins with large diameters should contain strong positive anomalies because of limited relaxation due to high viscosity of a cooler planet [6]. In contrast, a less pronounced gravity anomalies hint at higher relaxation due to lower viscosity and a hotter crust in the planet’s earlier history (Fig 3).

Fig. 3: Bouguer anomaly contrast from rim to centre versus rim diameter. Basin classes: b_deg- degraded basin (<50% rim preserved), centr_peak- central peak basin, peakr- peak ring basin, com- complex basin (>50% rim preserved).

Acknowledgements

This work is supported by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (SFB-TRR170, A6).

References

[1] Orgel et al., 2020, Re-examination of the Population, Statigraphy and Sequence of Mercurian Basins: Implications for Mercury’s Early Impact History and Comparison with the Moon, J. Geophys. Res. 125(8), doi:10.1029/2019JE006212

[2] Fassett C. I., et al., (2012), Large impact basins on Mercury: Global distribution, characteristics, and modification history from MESSENGER orbital data, J. Geophys. Res. 117, E00L08, doi:10.1029/2012JE004154

[3] Preusker et al., Towards high-resolution global topography of Mercury from MESSENGER orbital stereo imaging: A prototype model for the H6 (Kuiper) quadrangle, Planetary and Space Science 142 (2017) 26-37

[4] Konopliv et al., The Mercury gravity field, orientation, love number, and ephemeris from the MESSENGER radiometric tracking data, Icarus, Volume 335, 2020, 113386, ISSN 0019-1035,https://doi.org/10.1016/j.icarus.2019.07.020.

[5] Wieczorek, M., The gravity and topography of terrestrial planets, Treatise on geophysica, 2006

[6] Neumann et al., 2015. Lunar impact basins revealed by Gravity Recovery and Interior Laboratory measurements. Science Advances 1(9), 1-10.

How to cite: Szczech, C. C., Oberst, J., and Preusker, F.: Classification of Mercury’s Impact Basins, Based on Topography- and Gravity Signatures in MESSENGER Data, Europlanet Science Congress 2022, Granada, Spain, 18–23 Sep 2022, EPSC2022-595, https://doi.org/10.5194/epsc2022-595, 2022.

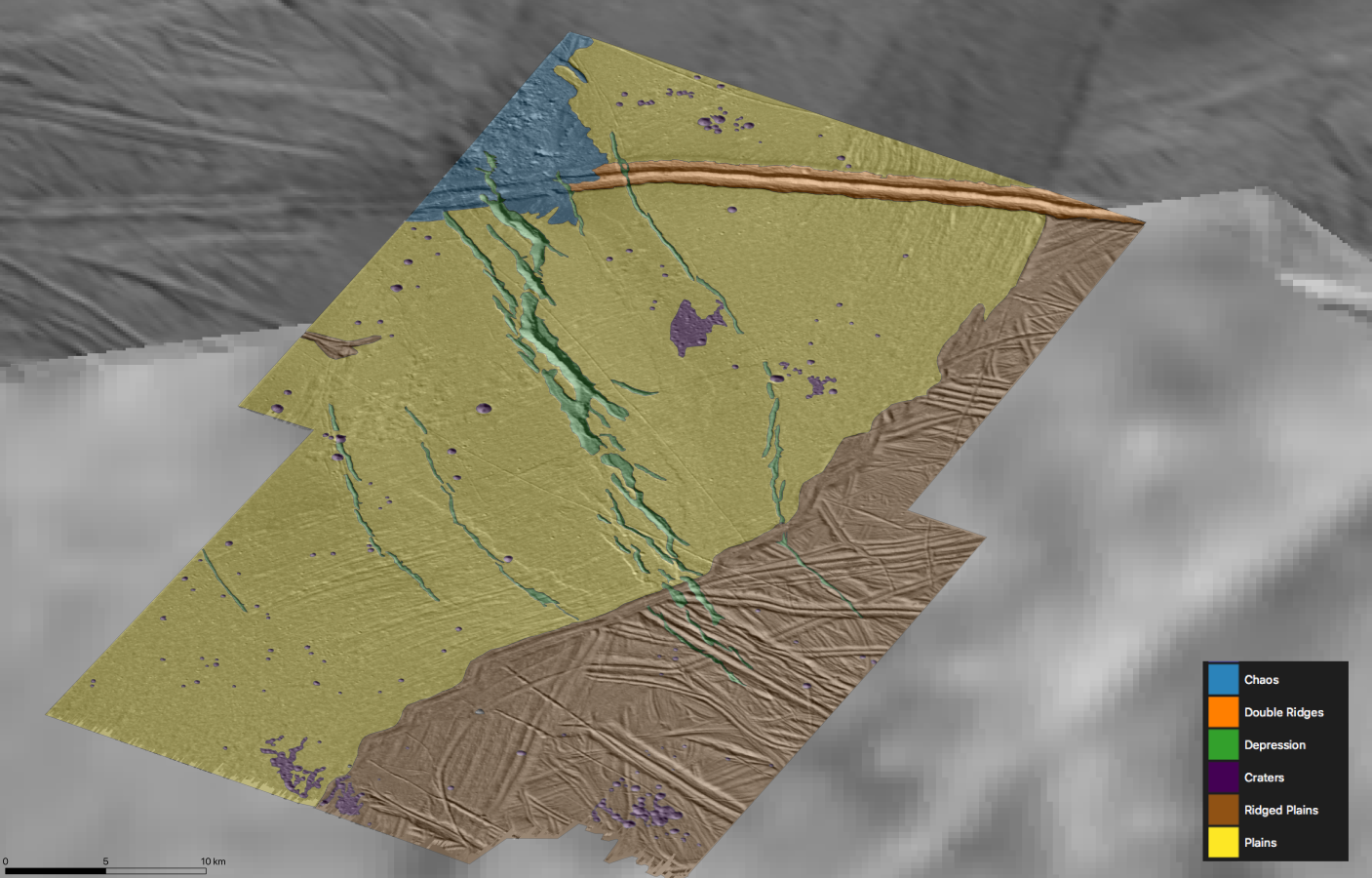

Data from NASA MESSENGER spacecraft highlighted that Mercury’s surface and composition are more varied than previously thought. Despite being the closest planet to the Sun, indeed, Mercury is rich in volatiles and its surface shows evidence of volatile-driven processes such as the formation of hollows and explosive volcanism. Even MESSENGER’s color-derived basemaps, moreover, highlight relevant color variations of the hermean surface possibly indicating age and compositional differences between adjacent materials.

The ongoing mapping for the eastern H9 Eminescu quadrangle (22.5°N-22.5°S, 108°E-144°E) [1] led to a thorough knowledge of the area that allowed the definition of scientific targets of interest to be investigated by the SIMBIO-SYS cameras [2] onboard the ESA-JAXA BepiColombo mission [3] coupled with other instruments such as MERTIS, BELA, MGNS and MIXS.

Proposed targets range from hollows to volcanic features, from craters and deformational structures and specific terrains and aim at shedding light on scientific questions concerning Mercury’s origin and evolution [4]. In particular, proposed targets aim to i) determine the abundance and distribution of key elements, minerals and rocks on the hermean crust, ii) characterize and correlate geomorphological features with compositional variations, iii) investigate the nature, evolution, composition and mechanisms of effusive and explosive events, iv) determine the formation and growth rates of hollows, the nature of processes related with volatile loss and their mineralogical and elemental composition of volatiles, v) determine the displacement and kinematics of tectonic deformations and the mechanisms responsible for their formation and vi) verify the occurrence of any detectable change in and around hollows and pyroclastic deposits since MESSENGER observations.

Acknowledgements: We acknowledge support from the Italian Space Agency (ASI) under ASI-INAF agreement 2017-47-H.0.

References: [1] El Yazidi et al., 2021, EPSC. [2] Cremonese et al., 2020, Sp. Sci. Rev. [3] Benkhoff et al., 2010, Plan. Sp. Sci. [4] Rothery et al., 2020, Sp. Sci. Rev.

How to cite: Tognon, G. and Massironi, M.: Definition of scientific targets of interest for BepiColombo in the eastern Eminescu (H9) quadrangle, Europlanet Science Congress 2022, Granada, Spain, 18–23 Sep 2022, EPSC2022-624, https://doi.org/10.5194/epsc2022-624, 2022.

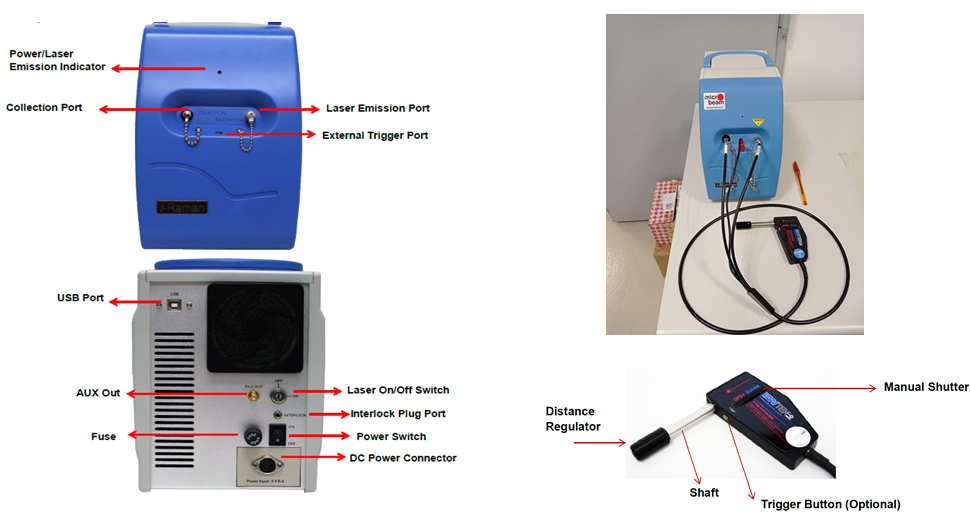

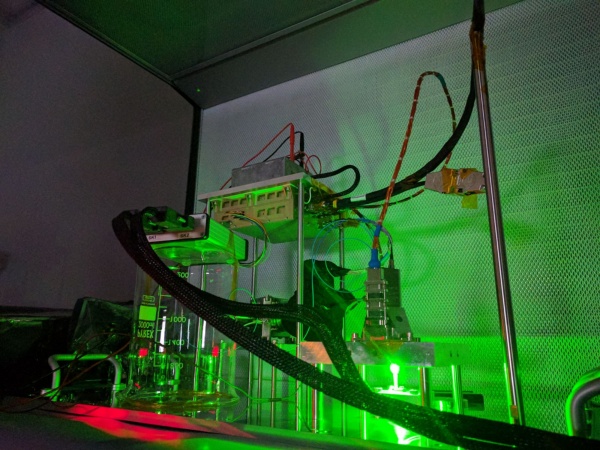

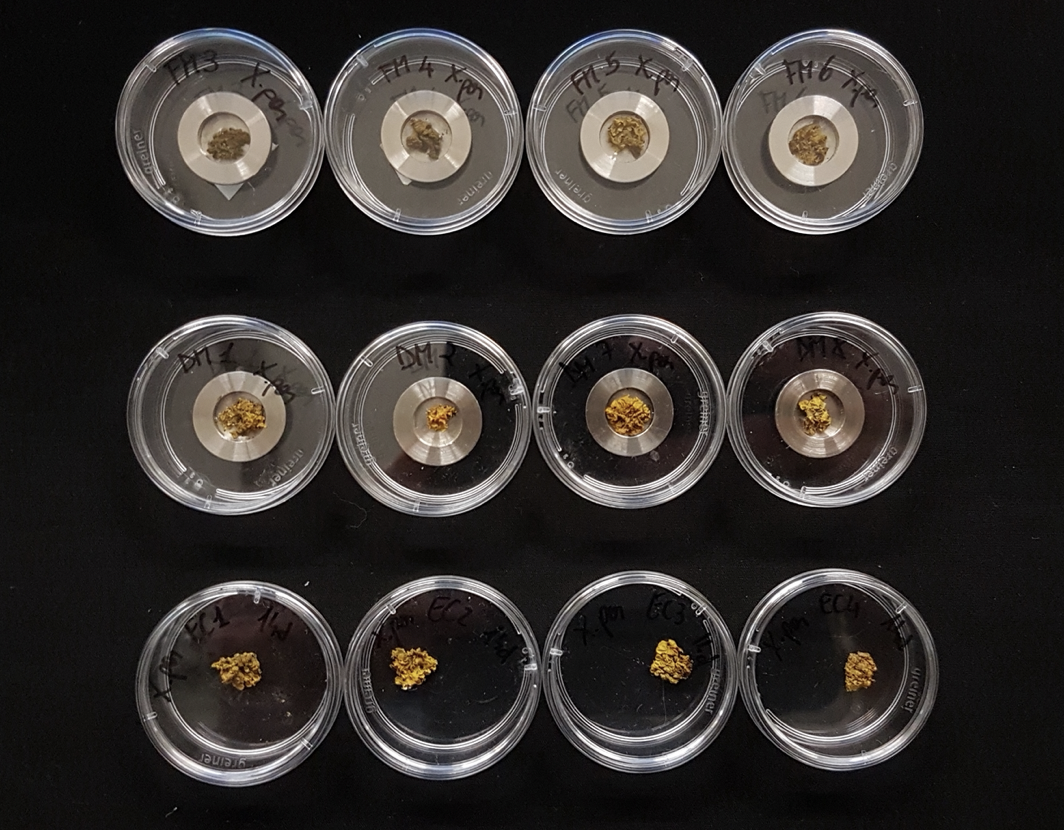

Introduction: The IRIS (Infrared and Raman for Interplanetary Spectroscopy) laboratory generates mid-infrared spectra for the ESA/JAXA BepiColombo mission to Mercury. Onboard is a mid-infrared spectrometer (MERTIS-Mercury Radiometer and Thermal Infrared Spectrometer), which will allow to map the mineralogy in the 7-14 µm range [1, 2]. In order to interpret the future data, a database of laboratory spectra is assembled at the Institut für Planetologie in Münster (IRIS) and the DLR in Berlin.

So far, we have studied for this purpose natural mineral and rock samples (e.g. 3, 4), impact melt rocks (e.g. 5, 6, 7) and meteorites (e.g. 8, 9, 10, 11). Furthermore, surface processes like regolith formations and space weathering were of interest (e.g. 12, 13, 14).

Synthetic analogue materials have become one of the foci of our work, since they allow to produce ‘tailor-made’ materials based on remote sensing data and/or modelling and experiments. These are closer than natural terrestrial materials, which formed usually under different conditions as expected on Mercury [e.g. 1]. We synthesized analogs for surface regions of Mercury and other planetary bodies (15, 16, 17).

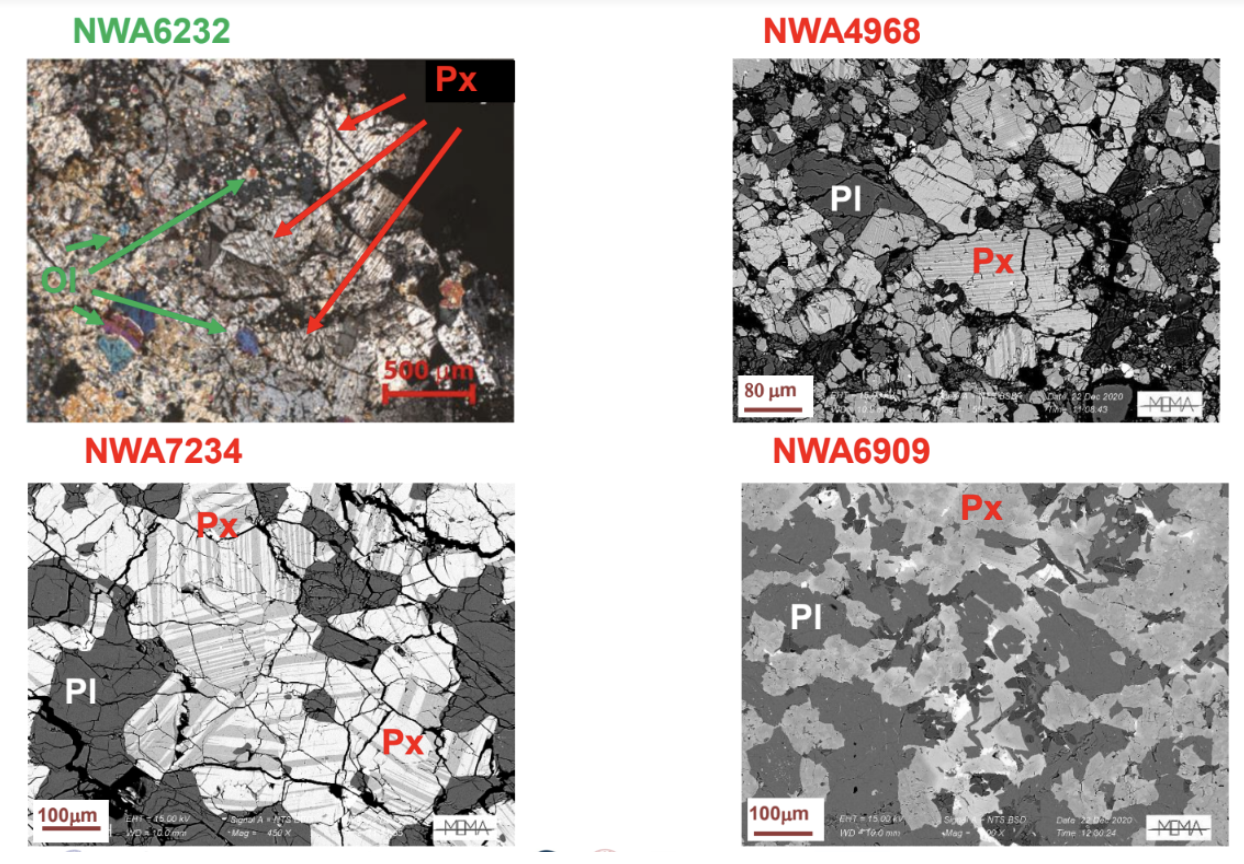

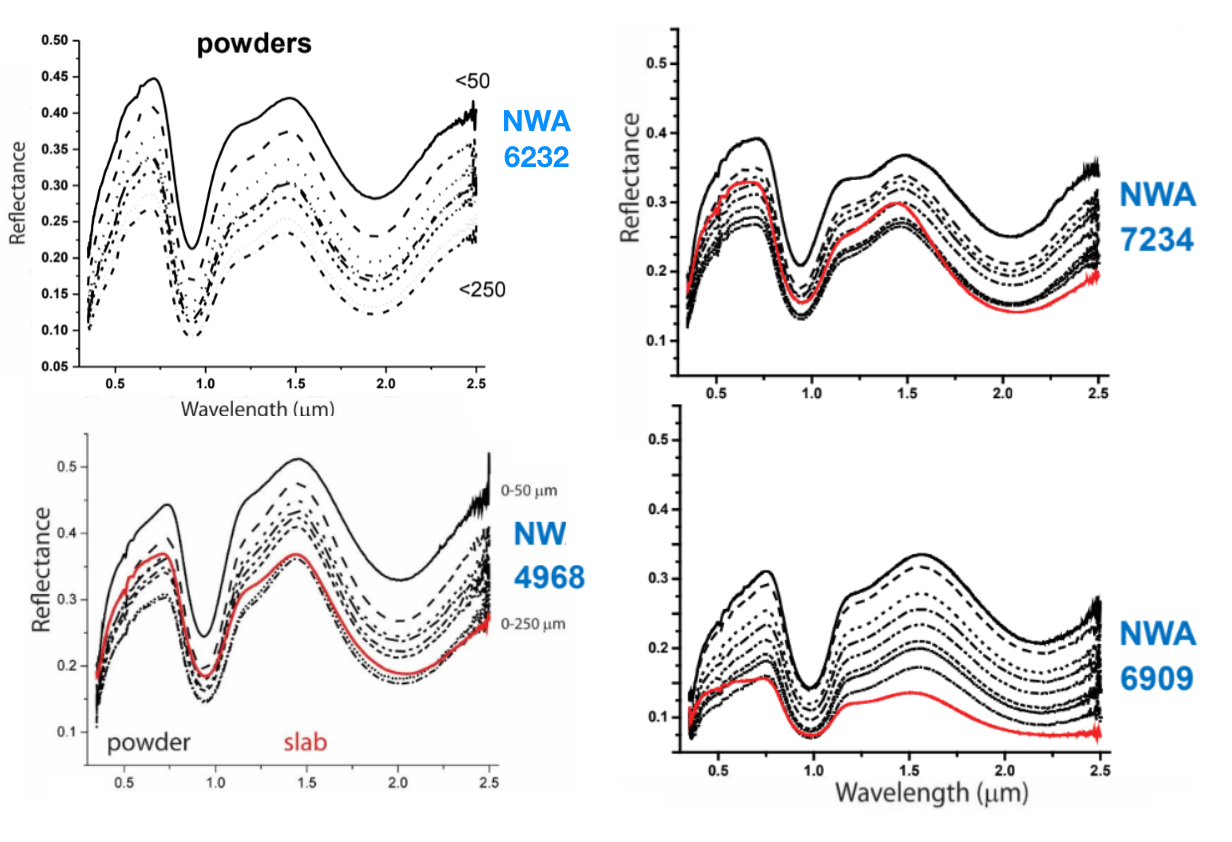

In this part of our study, we present mixtures based on phase equilibria of peridotite and partial melt compositions which were studied under hermean mantle conditions - temperature, pressure, oxygen fugacity (18,19,20). These experiments suggested that the crustal mineralogy should be dominated by variable abundances of plagioclase, olivine, clino- and orthopyroxene, with unconstrained proportions of silicate glass. Based on the model mineralogy of representative results, we produced mineral/glass mixtures based on the Low-Mg Northern Volcanic Plains (NVP)(Y121, Y131, Y172), High-Mg NVP (Y143, Y144), Smooth Plains (Y140, Y143, Y144), Inter crater Plain and Heavily Cratered Terrains (IcP-HCT) (Y126, Y131, Y132, Y146), and High-Mg Province (Y126, Y131, Y146) [20].

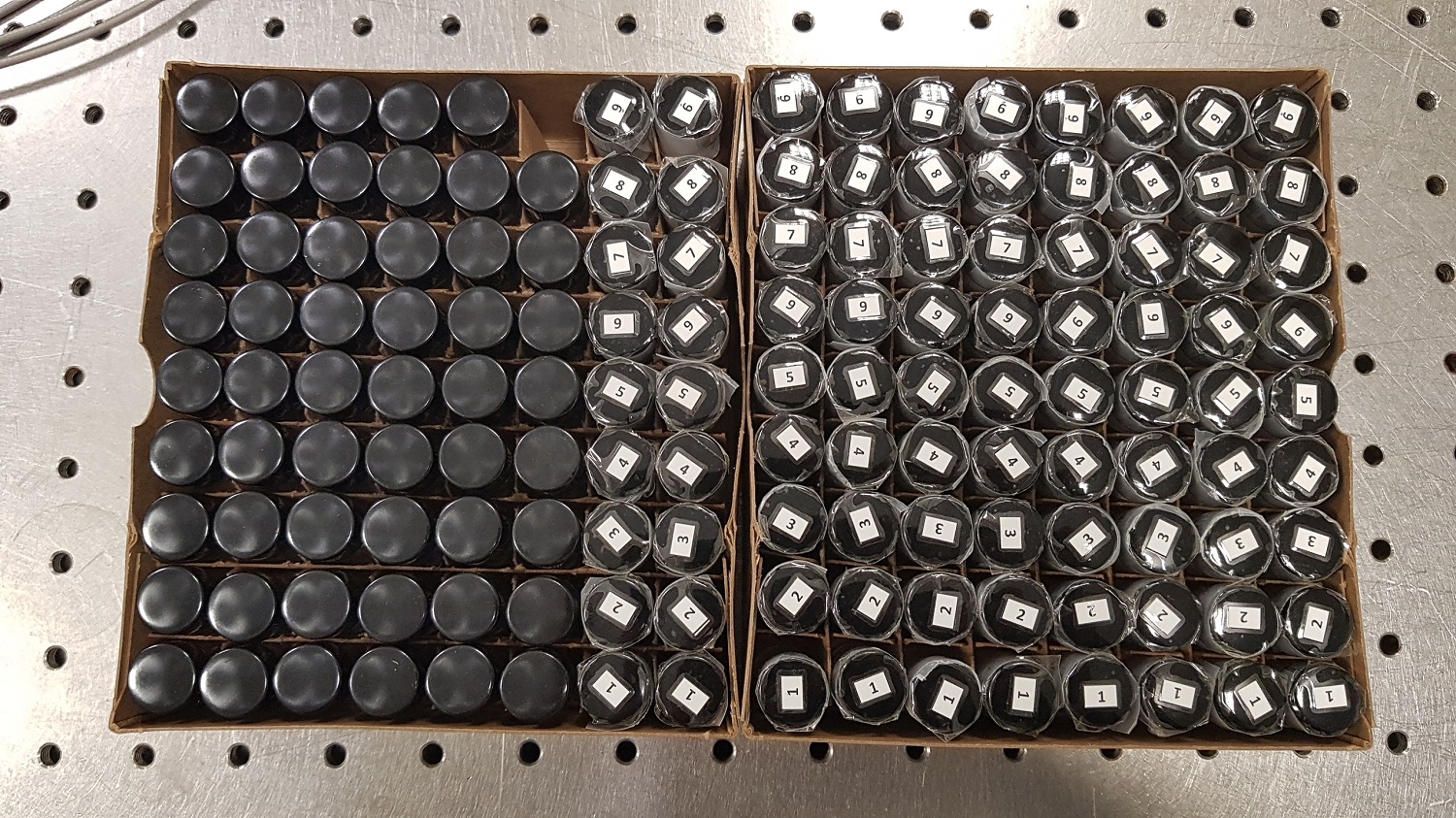

Samples and Techniques: We conducted diffuse reflectance studies of sieved size fractions (0-25 µm, 25-63 µm, 63-125 µm and 125-250 µm) under vacuum conditions, ambient heat, and variable geometries. We used a Bruker Vertex 70v with A513 variable geometry stage. The results will be made available in the IRIS Database [1].

Results: First results show the Christiansen Feature (CF), a characteristic, easy to identify reflectance low (or emission high) ranging from 7.9 µm to 8.2 µm (always average of all size fractions). The Transparency Feature (TF), typical for the finest size fraction (0-25 µm) is in many mineral mixtures less pronounced than for pure mineral phases. Here the individual TF of the components result in a broad feature.

The resulting spectra can be divided into three groups – such as dominated by a single glass feature at 9.6 – 9.9 µm, a second groups with forsterite bands 9.4 µm- 9.5 µm, 10.2 µm, 10.6 µm, 11.9 µm and 15.9 µm-16 µm, and a third dominated by pyroxene bands at 8.9-9.1 µm, 9.4-9.5 µm, 9.9 µm, 10.2 µm, 10.4-10.5 µm, 10.6 µm, 10.8-11 µm 11.1-11.3 µm and 11.4-11.6 µm. Plagioclase features, even when the phase is dominating the composition, are usually ‘overprinted’ by forsterite and pyroxene bands.

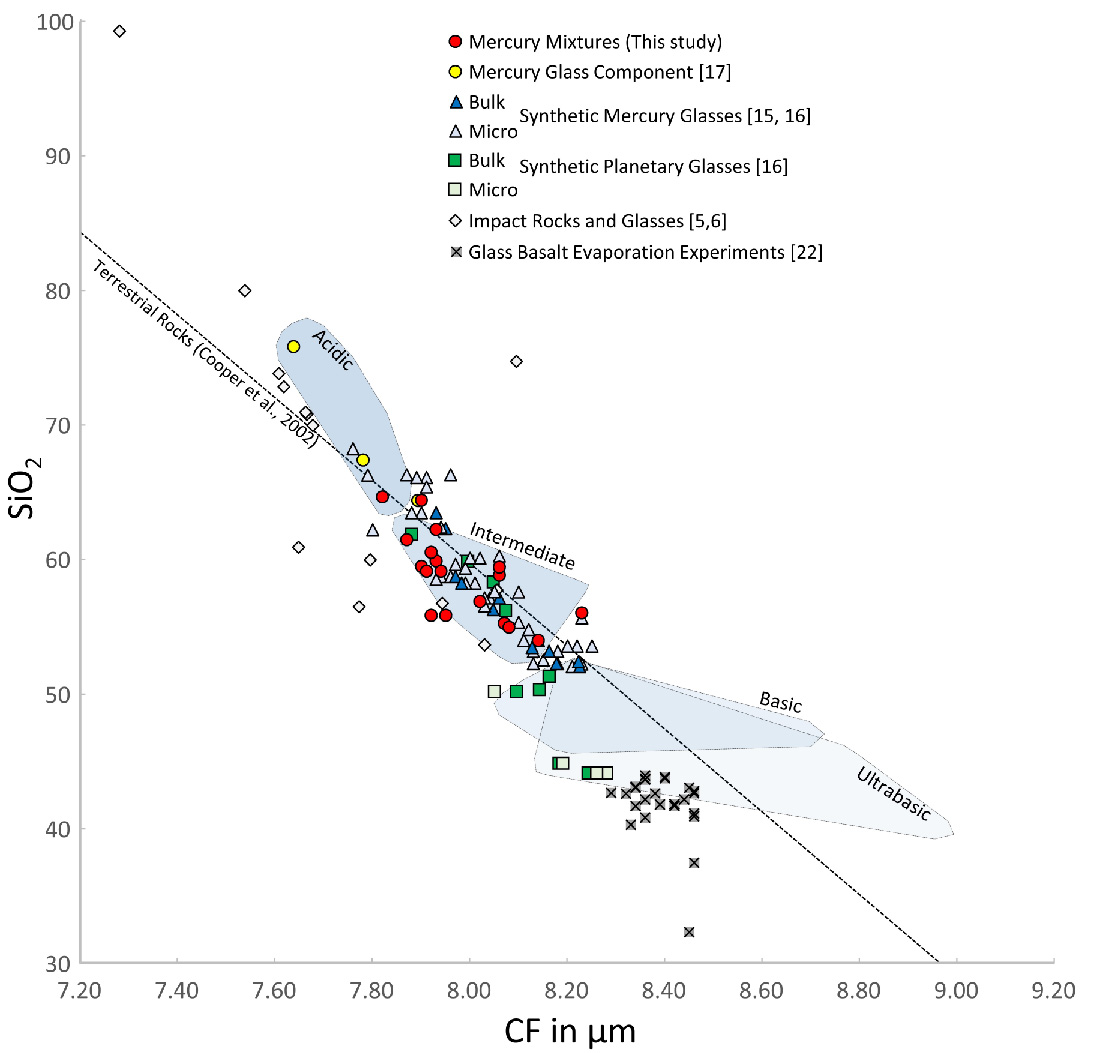

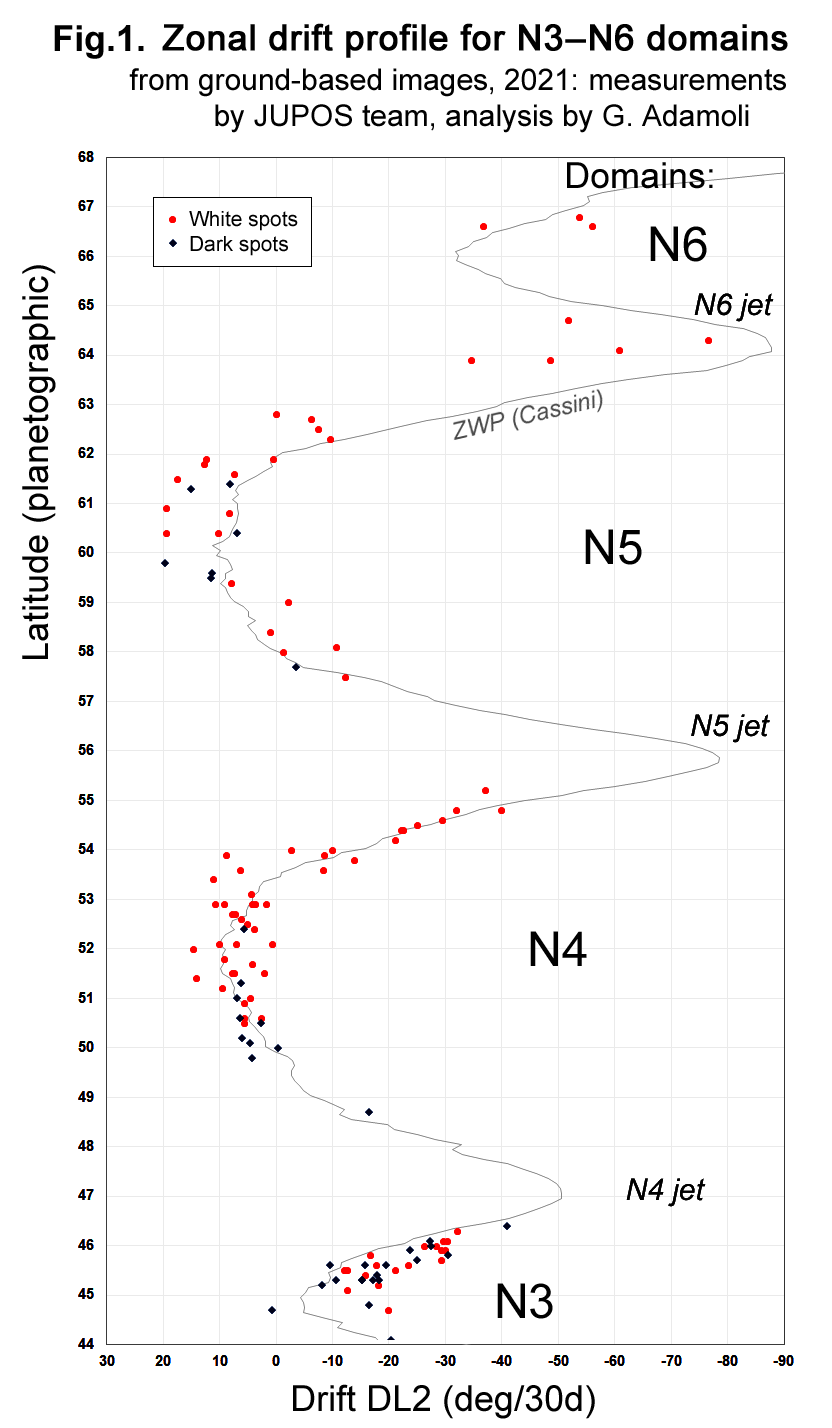

Discussion: A classic way to connect an easy to identify spectral feature in the mid-infrared to the chemical bulk composition is using the CF and the SiO2 content. Both show a strong correlation for both terrestrial rocks [21] and a variety of synthetic analogue samples from earlier studies in this project [15, 16, 17] (Fig.1).

Summary & Conclusion: In a next step, we will study these mixtures under more realistic conditions, i.e., high vacuum and high temperature, in order to better simulate the hermean surface. Also, these mixtures will be used to test spectral unmixing routines, which allow to identify abundances of single minerals in a complex mixture of phases.

References: [1] Hiesinger et al. (2020) Space Sci. rev. 216, 110 [2] Benkhoff et al. (2022) Space Sci. Rev. 217, 90 [3] Reitze et al.(2020) Min. Pet. 114, 453-463 [4] Reitze et al.(2021) EPSL 554, 116697 [5] Morlok et al.(2016) Icarus 264, 352-368 [6] Morlok et al.(2016) Icarus 278, 162-179 [7] Reitze et al.(2021) JGR (Planets) 126, e06832 [8] Weber et al. (2016) MAPS 51, 3-30 [9] Morlok et al. (2017) Icarus 284, 431-442 [10] Morlok et al. (2020) MAPS 55, 2080-2096 [11] Martin et al. (2017) MAPS 52, 1103-1124 [12] Weber et al. (2020) EPSL 530, 115884 [13] Weber et al. (2021) EPSL 569, 117072 [14] Stojic et al. (2021) Icarus 357, 114162 [15] Morlok et al. (2017) Icarus 296, 123-138 [16] Morlok et al. (2019) Icarus 324, 86-103 [17] Morlok et al. (2021) Icarus 361, 114363 [18] Charlier et al. (2013) EPSL 363, 50-60 [19] Namur et al. (2016) EPSL 439, 117-128 [20] Namur and Charlier (2017) Nature Geosci. 10, 9-13 [21] Cooper at al. (2002) JGR 107, 5017-5034 [22] Morlok et al. (2020) Icarus 335, 113410

Figure 1: Comparison of the Christiansen Feature (CF), a characteristic reflectance low, to the SiO2 bulk composition. The results from this study (red circles) fall along the regression line for terrestrial intermediate rocks.

How to cite: Morlok, A., Renggli, C., Charlier, B., Namur, O., Klemme, S., Reitze, M., Weber, I., Stojic, A. N., Bauch, K., Schmedemann, N., Pasckert, J.-H., Hiesinger, H., and Helbert, J.: Synthetic Analogs for Surface Regions on Mercury: A Mid-Infrared Study for the BepiColombo Mission, Europlanet Science Congress 2022, Granada, Spain, 18–23 Sep 2022, EPSC2022-876, https://doi.org/10.5194/epsc2022-876, 2022.

The low intensity and lack of small-scale variations in Mercury’s present-day magnetic field can be explained by a thermally stratified layer blanketing the convective liquid outer core. The presence of a present-day stable layer is supported by thermal evolution studies that show that a sub-adiabatic heat flow at the core-mantle boundary can occur during a significant fraction of Mercury’s history. The requirements for both the likely long-lived Mercury dynamo and the presence of a stable layer place important constraints on the interior structure and evolution of the core and planet.

We couple mantle and core thermal evolution to investigate the necessary conditions for a long-lived and present-day dynamo inside Mercury’s core by taking into account an evolving stable layer overlying the convecting outer core. Events such as the cessation of convection in the mantle may strongly influence the core-mantle boundary heat flow and affect the thickness of the thermally stratified layer in the core, highlight the importance of coupling mantle evolution with that of the core. We employ interior structure models that agree with geodesy observations and make use of recent equations of state to describe the thermodynamic properties of Mercury’s Fe-S-Si core for our thermal evolution calculations.

How to cite: Rivoldini, A., Deprost, M.-H., Zhao, Y., Knibbe, J., and Van Hoolst, T.: Effect of a thermally stratified layer in the outer core of Mercury on its internally generated magnetic field, Europlanet Science Congress 2022, Granada, Spain, 18–23 Sep 2022, EPSC2022-929, https://doi.org/10.5194/epsc2022-929, 2022.

Since the era of Messenger, many observational constraints on Mercury’s thermal evolution and magnetic field have strengthened the idea that the outermost layer of Mercury’s fluid core is stably stratified. The presence of such a stably stratified zone can significantly alter the core flow compared to the flow in a completely homogeneous fluid core. This is on the one hand because stratified layers can impede fluid motions that are parallel to the density gradient, which in the case of Mercury would mean that radial flows are strongly suppressed. On the other hand this is because a stably stratified layer can support different types of waves that are affected by the buoyancy force.

In this study we have created a numerical model to investigate flow in Mercury’s fluid outer core that includes a radial background stratification. The exact structure of the density profile in the planet’s core is unknown, and we assume profiles based on recent findings of the interior evolution of the planet. We studied core flow that is excited by Mercury’s librations, oscillations of the mean rotation rate due to the solar gravitational torque acting on Mercury’s triaxial shape. Based on the work by Rekier et. al. (2019) we represent the librational forcing by the superposition of three different decoupled motions: a horizontal component, which represents the viscous drag of the core fluid by the librating mantle and spherical inner core, and two radial components that are representing the radial push that the core flow would experience due to the librating triaxial boundaries.

We show that especially the second component has a profound effect, inducing a large non-axisymmetric flow close to the core-mantle boundary. It turns out that even though the origin of said flow is radial, the horizontal component of the flow is far larger than it’s radial counterpart. This indicates that the stratified layer acts to convert radial motions into strong horizontal motions.

We show how the strength and existence of this flow depend on the strength of the stratification of the layer and discuss implications of this flow for the magnetic field.

References:

Rekier, J., Trinh, A., Triana, S. A., & Dehant, V. (2019). Internal energy dissipation in Enceladus's subsurface ocean from tides and libration and the role of inertial waves. Journal of Geophysical Research: Planets, 124, 2198–2212. https://doi.org/10.1029/2019JE005988

How to cite: Seuren, F., Rekier, J., Triana, S. A., and Van Hoolst, T.: The core flow induced by Mercury’s libration: density stratification and magnetic fields, Europlanet Science Congress 2022, Granada, Spain, 18–23 Sep 2022, EPSC2022-934, https://doi.org/10.5194/epsc2022-934, 2022.

TP2 | Paving the way to the decade of Venus

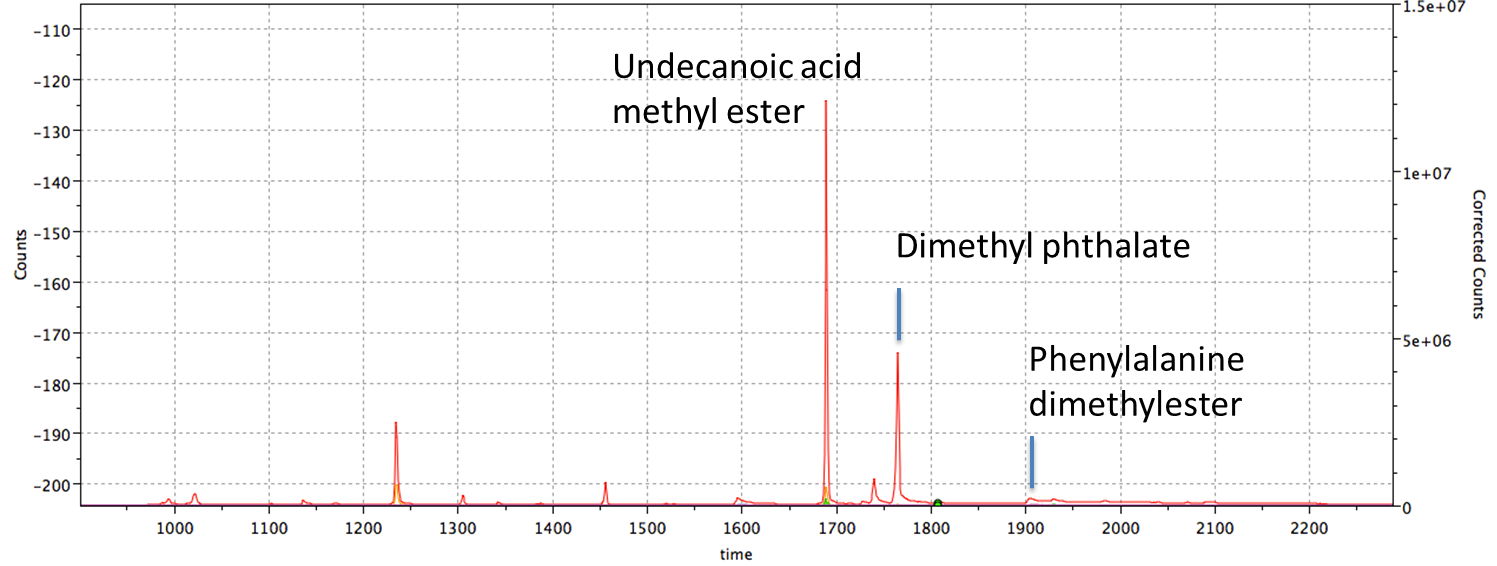

Background

In situ probe measurements and remote sensing have revealed that Venus has a highly organised cloud system. Comparisons between models of the expected spectra and observations reveal unexplained absorption in the near-UV to blue region of the spectrum. While many candidates for this “unknown absorber” have been proposed over the years, none have been conclusively demonstrated to match the physical and optical behaviour observed (Pérez-Hoyos et al., 2018, JGR Planets, 123).

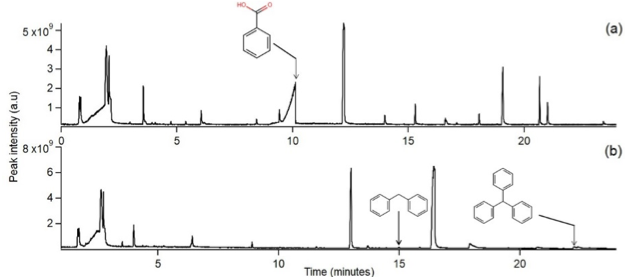

One such candidate is ferric chloride (Krasnopolsky, 2017, Icarus, 286; Zasova et al., 1981, ASR, 1). Attempts to reliably determine its suitability have been hampered by the scarcity of representative spectra available. Absorbance spectra generally used in the literature are measured in ethyl acetate (Aoshima et al., 2013, Polymer Chemistry, 4), and therefore may not be representative of the absorption produced by ferric chloride in the Venusian clouds.

In addition to the absorption spectrum produced, the behaviour of absorber candidates must also be considered, including their rates and locations of production and loss, transport mechanisms, and lifetimes in the atmosphere. While much of this behaviour must be examined in atmospheric models, laboratory studies to establish reaction pathways and measure rates are needed to provide as much quantitative data as possible for model development.

Method and results

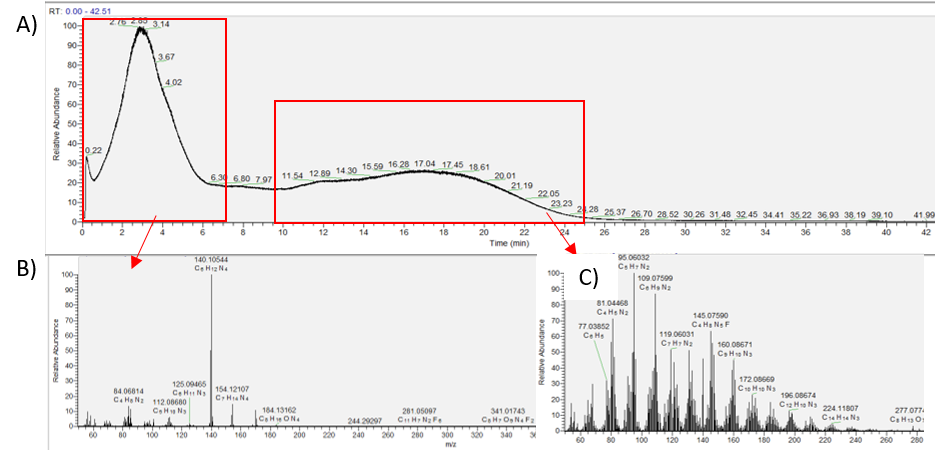

Literature spectra for ferric chloride employ UV-visible spectrometry using ethyl acetate as a solvent. We present absorption spectra of ferric chloride in sulphuric acid. This change of solvent produces an environment more closely aligned to that on Venus, where ferric chloride, if present, may exist as an impurity in the micron-sized sulphuric acid cloud droplets (Petrova, 2018, Icarus, 306).

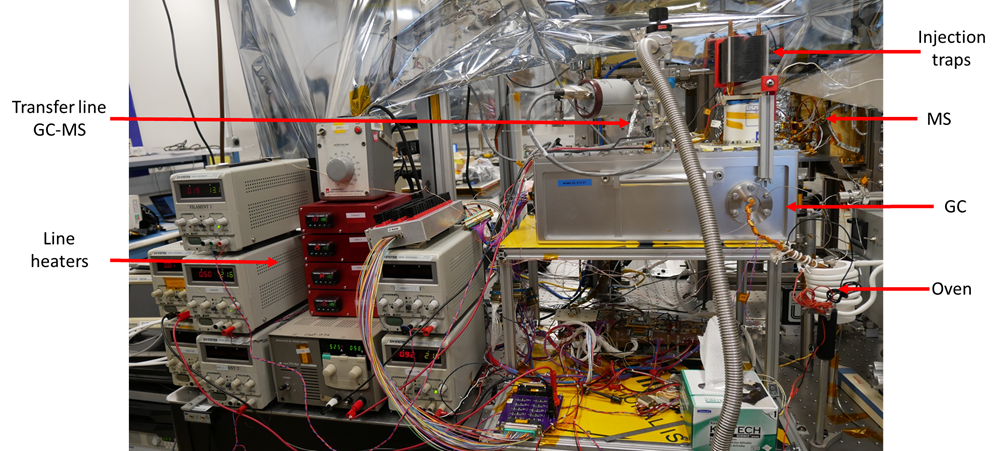

In addition, mass spectrometry was used to investigate the kinetics and products of reactions of ferric chloride that could occur in the Venusian atmosphere. Behaviour predicted by these experiments can then be included in atmospheric models to test the lifetime and transport of ferric chloride and its reaction products in the atmosphere.

Conclusions

The unknown absorption was first observed close to 100 years ago, yet the mystery of its cause remains unsolved. More representative spectra of ferric chloride and a greater understanding of its behaviour in the atmosphere of Venus are critical to advancing the identification of the unknown absorber. As the absorber is located towards the top of the clouds and absorbs in the near-UV to blue region, it is responsible for large amounts of absorption of incident sunlight, and therefore has a significant impact on the Venusian energy budget. Accurate atmospheric modelling of the planet therefore requires an understanding of the absorber which can only be achieved once it has been conclusively identified.

How to cite: Egan, J., James, A., Plane, J., Murray, B., and Feng, W.: Laboratory experiments to constrain the identity of Venus’s unknown UV absorber, Europlanet Science Congress 2022, Granada, Spain, 18–23 Sep 2022, EPSC2022-76, https://doi.org/10.5194/epsc2022-76, 2022.

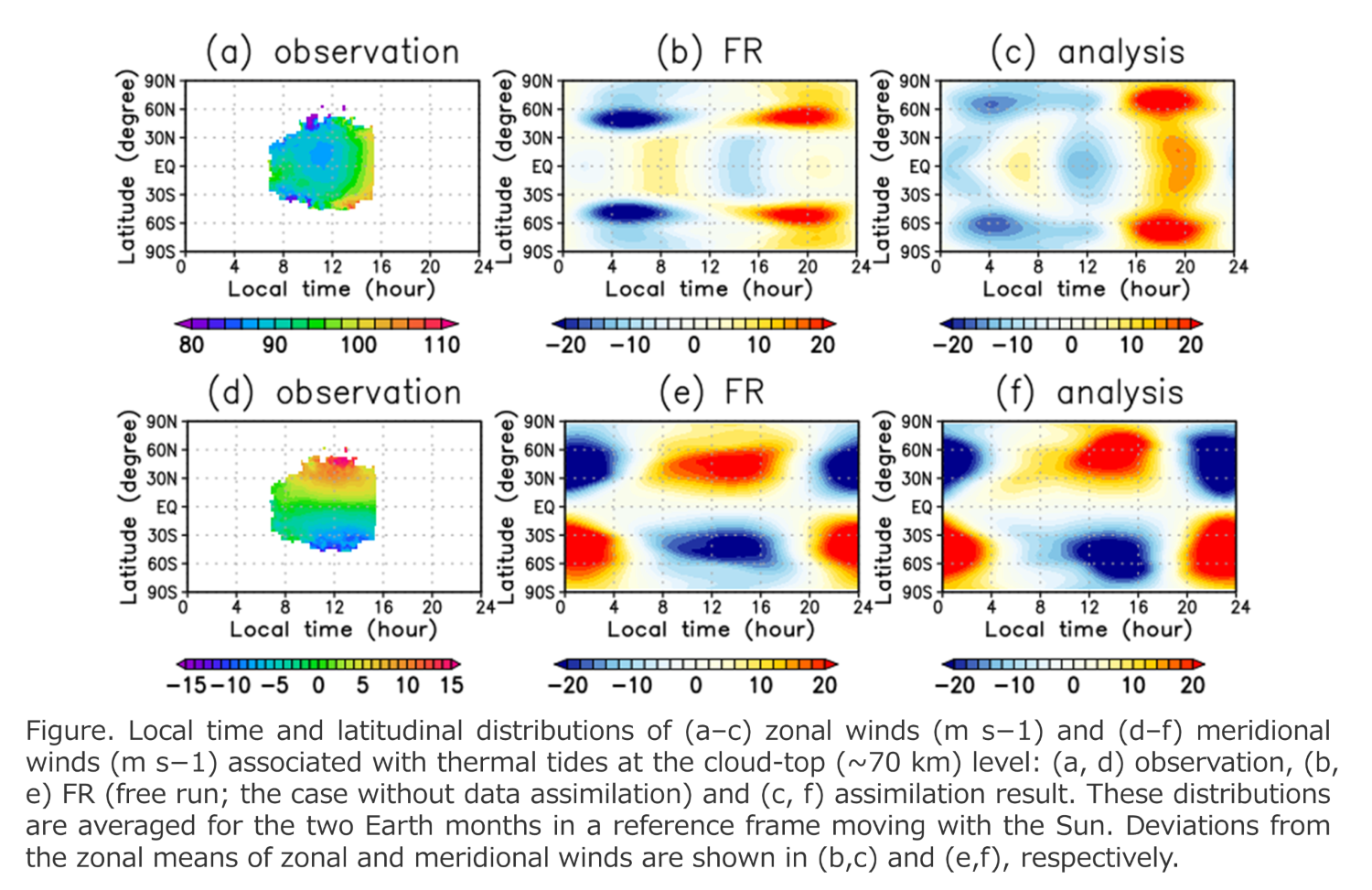

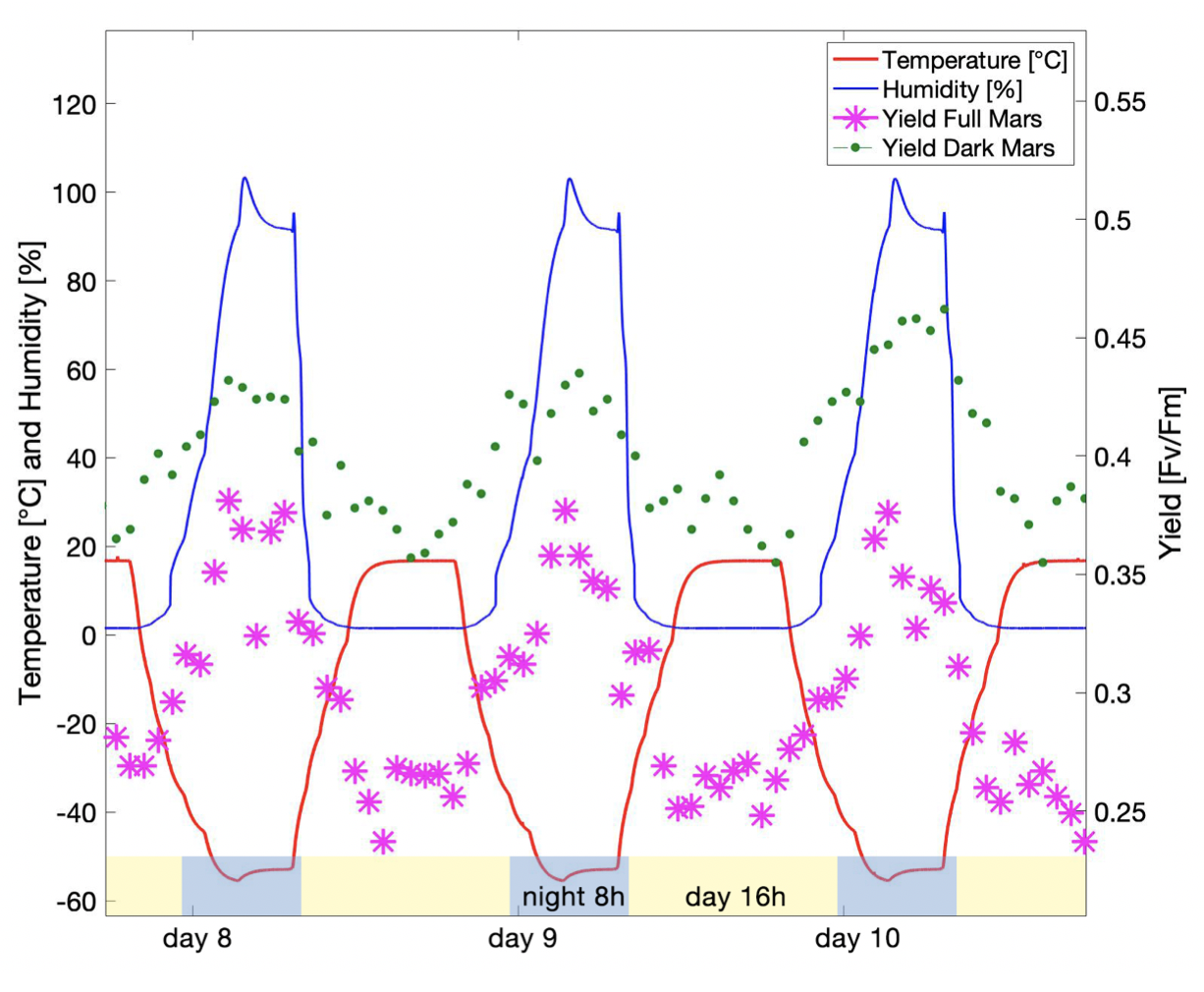

Observations of the Venus Climate Orbiter “Akatsuki” provide us with horizontal distributions of the horizontal winds derived from cloud tracking of the Ultraviolet Imager (UVI) and of temperature observed by the Longwave Infrared Camera (LIR). However, these observations are limited in altitude, local time (day or night side), and frequency. Then it is difficult to elucidate the general circulation of the Venus atmosphere, including various temporal and spatial scales, only from observations. In this study, we produced a Venus dataset (analysis) that has high temporal and spatial resolutions by assimilating horizontal winds derived by the Akatsuki observations. At the top of the cloud layer of Venus, there are planetary-scale atmospheric waves that are excited by the solar heating and move with the sun, called the thermal tides. In this presentation, we focused on thermal tides to verify the analysis.

We use the Venus atmospheric data assimilation system “ALEDAS-V" (Sugimoto et al., 2017) [1] for assimilation and the Venus atmospheric general circulation model “AFES-Venus" (Sugimoto et al., 2014) [2] for ensemble forecasts. AFES-Venus is a full nonlinear dynamical GCM on the assumption of hydrostatic balance, designed for the Venus atmosphere. ALEDAS-V uses the Local Ensemble Transform Kalman Filter, and is the first data assimilation system for the Venus atmosphere. We assimilated the cloud top (~70km) zonal and meridional winds obtained by tracking morphology, using Akatsuki UVI data (Horinouchi et al., 2021) [3] from September 1st to December 31st, 2018. The assimilation data (analysis) from October 1st to November 30th, 2018, is analyzed, because the root-mean-square-deviations (RMSD) from FR (free run; the case without data assimilation) are stable.

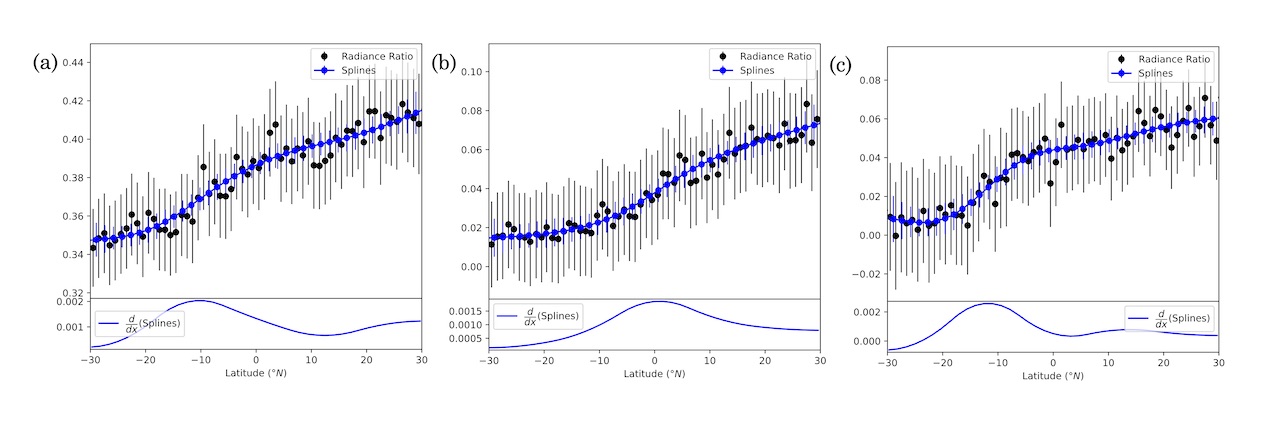

Figures (a) and (d) show the observed zonal and meridional winds, respectively. The zonal wind has a local minimum near 11 LT (local time) around the equator (Figure a). The meridional wind is the weakest at the equator and increases with latitude, and the amplitude is maximum around noon (Figure d) in the local time direction. Note that these winds obtained from observations exist only the dayside equatorward of 50° latitudes (Figure a and d).

Figures (b) and (e) show the deviations from the zonal means of zonal and meridional winds at an altitude of 70 km in the FR, respectively. For zonal wind, diurnal (zonal wavenumber 1) and semidiurnal (zonal wavenumber 2) tides are dominant at latitudes poleward and equatorward of 30, respectively (Figure b). The zonal wind deviation has a local minimum at 14-15LT, which is ~ 2 hours behind the observation (Figures a and b). The meridional wind deviation is polar and equatorial on the dayside and nightside, respectively (Figure e), and this distribution is consistent with Akatsuki's observation (Figure d).

Figures (c) and (f) show the zonal and meridional winds as a result of assimilation, respectively. The zonal wind in the equatorial region have a local minimum near 11 LT. The assimilation improved the semidiurnal tide closer to the observations (Figures a and c). The meridional wind is not so different from FR. This is probably because FR was originally very similar to observations (Figures d and f). These results are consistent with a previous study by Sugimoto et al. (2019) [4]. In addition, while the observed winds exist only on the dayside, the results of assimilation show that the horizontal winds field is modified significantly even on the nightside. It is suggested that spatially limited data assimilation can improve the general circulation of GCM.

In the future work, we are planning to release the assimilation dataset as the “objective analysis data” of Venus for the first time in the world.

[1] Sugimoto, N., et al. Development of an ensemble Kalman filter data assimilation system for the Venusian atmosphere. Scientific Reports 7(1), 9321 (2017).

[2] Sugimoto, N., et al. Baroclinic instability in the Venus atmosphere simulated by GCM. J. Geophys. Res. Planets 119, 1950–1968 (2014).

[3] Horinouchi, T., et al. Venus Climate Orbiter Akatsuki Cloud Motion Vector Data Set v1.0, JAXA Data Archives and Transmission System (2021).

[4] Sugimoto, N., et al. Impact of data assimilation on thermal tides in the case of Venus Express wind observation. Geophys. Res. Lett. 46, 4573–4580 (2019).

How to cite: Fujisawa, Y., Murakami, S., Sugimoto, N., Takagi, M., Imamura, T., Horinouchi, T., Hashimoto, G. L., Ishiwatari, M., Enomoto, T., Miyoshi, T., Kashimura, H., and Hayashi, Y.-Y.: Thermal tides reproduced in the assimilation results of horizontal winds obtained from Akatsuki UVI observations, Europlanet Science Congress 2022, Granada, Spain, 18–23 Sep 2022, EPSC2022-309, https://doi.org/10.5194/epsc2022-309, 2022.

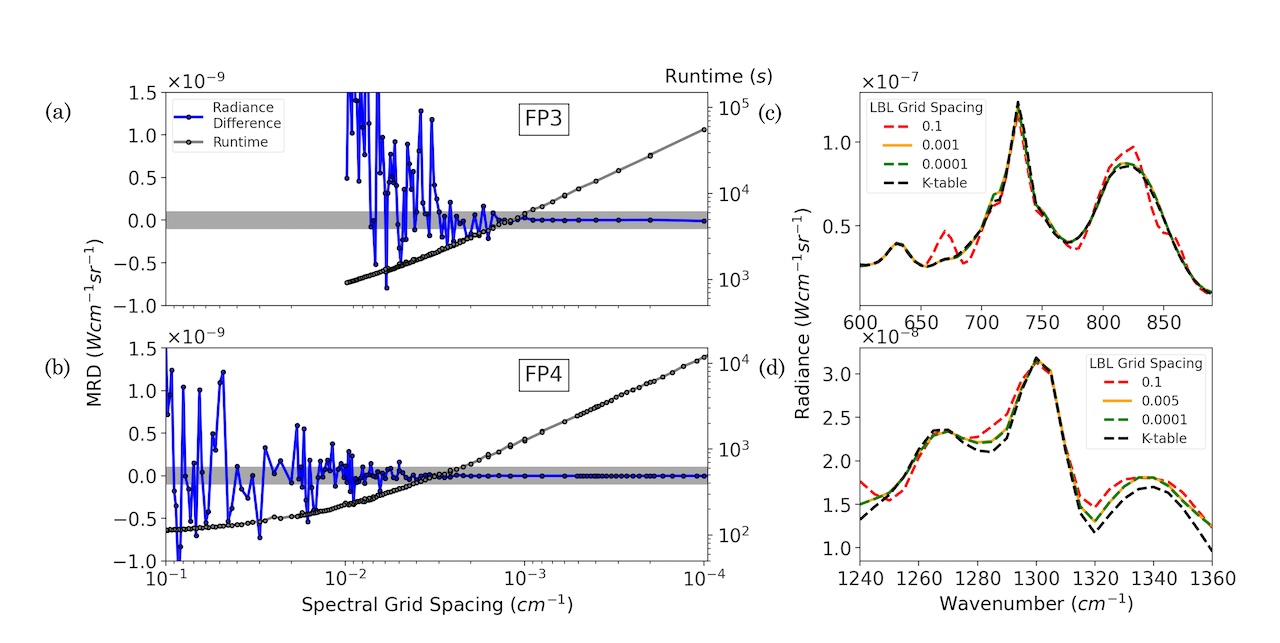

Since 2012, we have been monitoring SO2 and H2O (using HDO as a proxy) at the cloud top of Venus, using the TEXES high-resolution imaging spectrometer at the NASA InfraRed Telescope Facility (IRTF) at Maunakea Observatory. Sixteen runs have been performed between 2012 and 2022. Maps have been recorded around 1345 cm-1 (7.4 microns, z = 62 km), where SO2, CO2 and HDO are observed, and around 530 cm-1 (19 microns, z = 57 km) where SO2 and CO2 are observed, as well as around 1162 cm-1 (8.6 microns, z = 66 km) where CO2 is observed. From the early beginning, SO2 plumes have been identified with an evolution time scale of a few hours. In 2020, an anti-correlation has been found in the long-term evolution of H2O and SO2; in addition, the SO2 plume appearance as a function of local time seems to show two maxima around the terminator, indicating the possible presence of a semi-diurnal wave (Encrenaz et al. A&A 639, A69, 2020). After two years of interruption due to the pandemia, new observations have been performed in July 2021, September 2021, November 2021, and February 2022. The main results of the new observations are listed below. (1)The SO2 abundance, which had been globally increasing from 2014 until 2019, has now decreased with respect to its maximum value. (2) The anti-correlation between H2O and SO2, which was maximum between 2014 and 2019 (cc = - 0.9) does not appear clearly in the recent observations. (3) The maximum appearance of the SO2 plumes at the equator and the terminators is confirmed, but appears stronger on the morning side.(4) A strong activity of the SO2 plumes is observed in September and November 2021, at a time when the disk-integrated SO2 abundance is low. At the same time, thermal maps at 1162 cm-1 (8.6 microns, z = 66 km) show a polar enhancement. This behavior could possibly be associated with the topography.

How to cite: Encrenaz, T., Greathouse, T., Giles, R., Widemann, T., Bézard, B., and Fouchet, T.: Ground-based HDO and SO2 thermal mapping on Venus between 2012 and 2022: : An update, Europlanet Science Congress 2022, Granada, Spain, 18–23 Sep 2022, EPSC2022-414, https://doi.org/10.5194/epsc2022-414, 2022.

Numerical simulation of Venus’ atmosphere is useful to understand the dynamics of the system. The Venus atmospheric data assimilation system “ALEDAS-V” (Sugimoto et al. 2017) based on the Venus atmospheric general circulation model “AFES-Venus” (Sugimoto et al. 2014) has been used to simulate Venus’ atmosphere and generated some key phenomena such as the super-rotation, baroclinic waves, and thermal tides. To further understand the dynamics of Venus’ atmosphere, Bred Vectors (BV) are computed with the AFES-Venus model. This method can identify different growing modes of the system and has been used to study the dynamics of the Earth (Toth and Kalnay 1993, 1997) and Martian atmospheres (Greybush et al. 2013). However, to our knowledge, there has been no similar study on Venus’ atmosphere. To conduct the breeding cycle, we first produced a five (Earth) year free run of the AFES-Venus model initialized from an idealized zonal wind profile. Next, the forecast states on January 01 and August 25 in the 5th Earth year are used as the initial conditions for the control run and the perturbed run, respectively. These two initial conditions have the same sub-solar positions. To emphasize the active dynamics, the BV norm is defined by the temperature norm from the 60 km to 80 km altitudes, weighted by pressure and latitude. For the breeding cycle, a rescaling norm and rescaling interval are specified. During the breeding cycle, at every rescaling interval (including the initial time), if the norm is bigger than the specified rescaling norm, the BV is rescaled to the rescaling norm.

Different combinations of the parameters are tested. The BV amplitude generally remains stable throughout the whole year without significant seasonal variability (Figure 1), which is different from the Martian atmosphere. The growth rate of the BV amplitude can represent the characteristics of the instabilities. It is calculated by taking the natural logarithm of the ratio of the BV amplitude at the end of the time interval (before rescaling) to the amplitude at the beginning of the interval. It is then converted to the daily growth rate by dividing the ratio of the time interval to one day. When the rescaling norm is smaller or the rescaling interval is shorter, the average growth rate is higher (Figure 2). Further BV analysis will be conducted such as analyzing the BV structure by taking composite mean along the super-rotation and conducting BV breeding cycle without thermal tides. These results will be useful to understand the dynamics of the thermal tide, baroclinic waves, super-rotation, and other important features of Venus atmosphere.

Figure 1. The bred vector amplitude (K2 ) time evolution from the experiments with different rescaling days (1, 2, 5, 10, 20) and the same rescaling norm (10 K2 ).

Figure 2. The average daily growth rate of the bred vector amplitude (K2 ) for different combination of rescaling norm and rescaling days. The average is taken from February to December.

Reference

Greybush, S. J., E. Kalnay, M. J. Hoffman, and R. J. Wilson, 2013: Identifying Martian atmospheric instabilities and their physical origins using bred vectors. Q. J. R. Meteorol. Soc., 139, 639–653, https://doi.org/10.1002/qj.1990.

Sugimoto, N., M. Takagi, and Y. Matsuda, 2014: Baroclinic instability in the Venus atmosphere simulated by GCM. J. Geophys. Res. Planets, 119, 1950–1968, https://doi.org/10.1002/2014JE004624.

——, A. Yamazaki, T. Kouyama, H. Kashimura, T. Enomoto, and M. Takagi, 2017: Development of an ensemble Kalman filter data assimilation system for the Venusian atmosphere. Sci. Rep., 7, 9321, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-09461-1.

Toth, Z., and E. Kalnay, 1993: Ensemble Forecasting at NMC: The Generation of Perturbations. Bull. Am. Meteorol. Soc., 74, 2317–2330, https://doi.org/10.1175/1520-0477(1993)074<2317:EFANTG>2.0.CO;2.

——, and ——, 1997: Ensemble Forecasting at NCEP and the Breeding Method. Mon. Weather Rev., 125, 3297–3319, https://doi.org/10.1175/1520-0493(1997)125<3297:EFANAT>2.0.CO;2.

How to cite: Liang, J., Sugimoto, N., and Miyoshi, T.: Identifying the growing modes of Venus’ atmosphere using Bred Vectors, Europlanet Science Congress 2022, Granada, Spain, 18–23 Sep 2022, EPSC2022-713, https://doi.org/10.5194/epsc2022-713, 2022.

We report on detection and upper-limit of H2CO, O3, NH3, HCN, N2O, NO2, and HO2 above the cloud deck using the SOIR instrument on-board Venus Express.

The SOIR instrument performs solar occultation measurements in the IR region (2.2 - 4.3 µm) at a resolution of 0.12 cm-1, the highest of all instruments on board Venus Express. It combines an echelle spectrometer and an AOTF (Acousto-Optical Tunable Filter) for the order selection. SOIR performed more than 1500 solar occultation measurements leading to about two millions spectra.

The wavelength range probed by SOIR allows a detailed chemical inventory of the Venus atmosphere at the terminator in the mesosphere, with an emphasis on vertical distribution of the gases.

In this work, we report detections in the mesosphere, between 60 and 100 km.

Implications for the mesospheric chemistry will also be addressed.

How to cite: Mahieux, A., Robert, S., Mills, F., Trompet, L., Aoki, S., Piccialli, A., Jessup, K. L., and Vandaele, A. C.: Minor species in the Venus mesosphere from SOIR on board Venus Express: detection and upper limit profiles of H2CO, O3, NH3, HCN, N2O, NO2, and HO2, Europlanet Science Congress 2022, Granada, Spain, 18–23 Sep 2022, EPSC2022-921, https://doi.org/10.5194/epsc2022-921, 2022.

Venus appears to be an “alien” planet drastically and surprisingly different from the Earth. The early space missions revealed the world with remarkably hot, dense, cloudy, and very dynamic atmosphere filled with toxic species likely of volcanic origin. During more than 8 years of operations ESA’s Venus Express spacecraft performed a global survey of the atmosphere and plasma environment of our near neighbour. The mission delivered comprehensive data on the temperature structure, the atmospheric composition, the cloud morphology, the atmospheric dynamics, the solar wind interaction and the escape processes. Vertical profiles of the atmospheric temperature showed strong latitudinal trend in the mesosphere and upper troposphere correlated with the changes in the cloud top structure and suggesting convective instability in the main cloud deck at 50-60 km. Observations revealed significant latitudinal variations and temporal changes in the global cloud top morphology, which modulate the solar energy deposited in the atmosphere. The cloud top altitude varies from ~72 km in the low and middle latitudes to ~64 km in the polar region, correlated with decrease of the aerosol scale height from 4 ± 1.6 km to 1.7 ± 2.4 km, marking vast polar depression. UV imaging showed for the first time the middle latitudes and polar regions in unprecedented detail. In particular, the eye of the Southern polar vortex was found to be a strongly variable feature with complex dynamics.

Solar occultation observations and deep atmosphere spectroscopy in spectral transparency “windows” mapped distribution of the major trace gases H2O, SO2, CO, COS and their variations above and below the clouds, revealing key features of the dynamical and chemical processes at work. A strong, an order of magnitude, increase in SO2 cloud top abundance with subsequent return to the previous concentration was monitored by Venus Express specrometres. This phenomenon can be explained either by a mighty volcanic eruption or atmospheric dynamics.

Tracking of cloud features provided the most complete characterization of the mean atmospheric circulation as well as its variability. Low and middle latitudes show an almost constant with latitude zonal wind speed at the cloud tops and vertical wind shear of 2-3 m/s/km. Surprisingly the zonal wind speed was found to correlate with topography decreasing from 110±16 m/s above lowlands to 84±20 m/s at Aphrodite Terra suggesting decelerating effect of topographic highs. Towards the pole, the wind speed drops quickly and the apparent vertical shear vanishes. The meridional cloud top wind has poleward direction with the wind speed ranging from about 0 m/s at equator to about 15 m/s in the middle latitudes. A reverse equatorward flow was found about 20 km deeper in the middle cloud suggesting existence of a Hadley cell or action of thermal tides at the cloud level. Comparison of the thermal wind field derived from temperature sounding to the cloud-tracked winds confirms the validity of cyclostrophic balance, at least in the latitude range from 30S to 70S. The observations are supported by the General Circulation Models.

Venus Express detected and mapped non-LTE infrared emissions in the lines of O2, NO, CO2, OH originating near the mesopause at 95-105 km. The data show that the peak intensity occurs in average close to the anti-solar point for O2 emission, which is consistent with current models of the thermospheric circulation. For almost complete solar cycle the Venus Express instruments continuously monitored the induced magnetic field and plasma environment and established the global escape rates of 3·1024s−1, 7·1024s−1, 8·1022s−1 for O+, H+, and He+ ions and identified the main acceleration process. For the first time it was shown that the reconnection process takes place in the tail of a non-magnetized body. It was confirmed that the lightning tentatively detected by Pioneer-Venus Orbiter indeed occurs on Venus.

Thermal mapping of the surface in the near-IR spectral “windows” on the night side indicated the presence of recent volcanism on the planet, as does the high and strongly variable SO2 abundance. Variations in the thermal emissivity of the surface observed by the VIRTIS imaging spectrometer indicated compositional differences in lava flows at three hotspots. These anomalies were interpreted as a lack of surface weathering suggesting the flows to be younger than 2.5 million years indicating that Venus is actively resurfacing. The VMC camera provided evidence of transient bright spots on the surface that are consistent with the extrusion of lava flows that locally cause significantly elevated surface temperatures. The very strong spatial correlation of the transient bright spots with the extremely young Ganiki Chasma, their similarity to locations of rift-associated volcanism on Earth, provide strong evidence of their volcanic origin and suggests that Venus is currently geodynamically active.

Alongside observations of Earth, Mars and Titan, observation of Venus allows the opportunity to study geophysical processes in a wide range of parameter space. Furthermore, Venus can be considered as an archetype of terrestrial exoplanets that emphasizes an important link to the quickly growing field of exoplanets research.

The talk will give an overview of the Venus Express findings including recent results of data analysis, outline outstanding unsolved problems and provide a bridge, via the Akatsuki mission, to the missions to come in 2030s: EnVision, VERITAS and DAVINCI.

How to cite: Titov, D., Straume-Lindner, A. G., and Wilson, C.: Venus Express as precursor of the Venus Decade, Europlanet Science Congress 2022, Granada, Spain, 18–23 Sep 2022, EPSC2022-1120, https://doi.org/10.5194/epsc2022-1120, 2022.

TP3 | Forward to the Moon: The Science of Exploration

1. Introduction

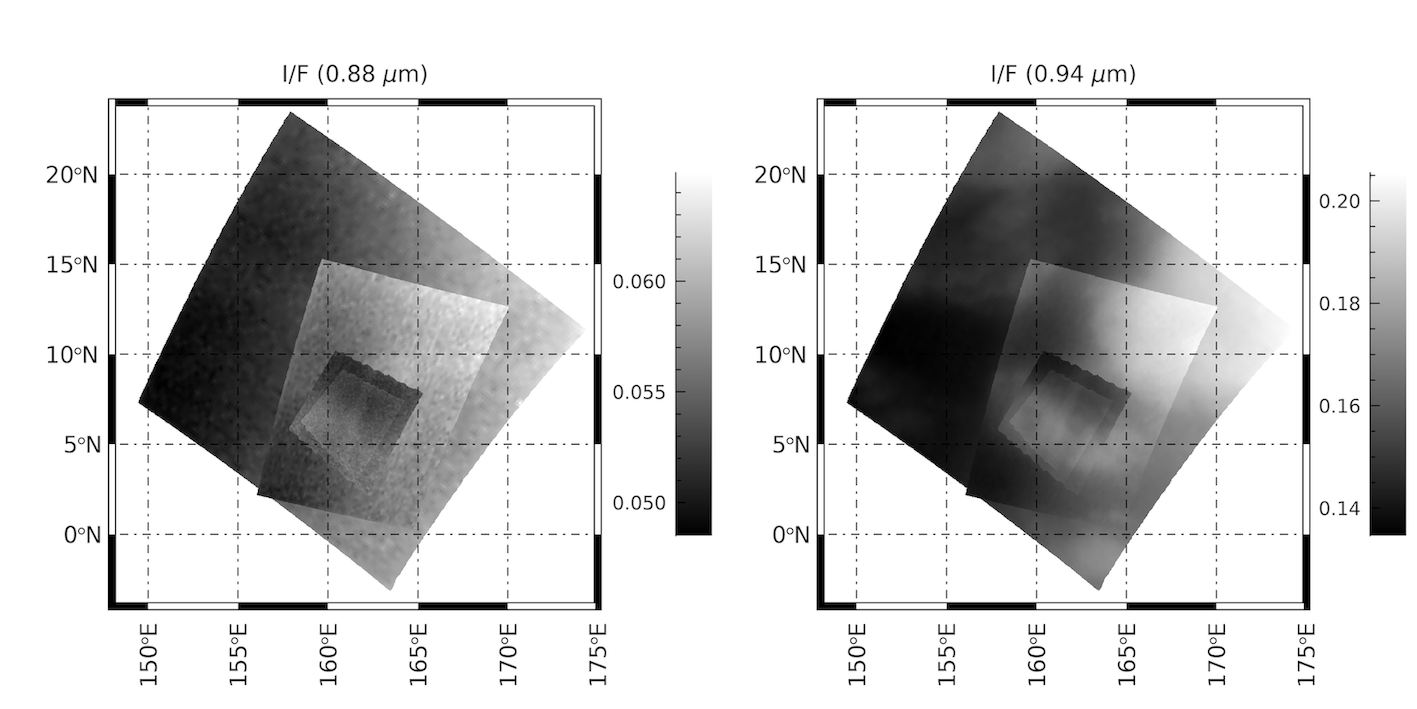

Knowing the photometric properties of a surface can give us insight into its physical properties. Images with several different observation conditions can be used to constrain the parameters of a semi-physical model like the Hapke model [1].

The Wide Angle Camera onboard the Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter (LROC WAC) [2] provides unprecedented coverage of the lunar surface for a variety of phase angles. The field of view of the Narrow Angle Camera (LROC NAC) [2] is much smaller and therefore, also the possible phase angles are limited but the resolution is around 1 m/pixel.

Sato et al. [3] have used WAC images to create global maps of the Hapke parameters binned into areas of 1 degree/pixel [3]. In this work, we calculate photometric parameters on the pixel level. Velikodsky et al. [4] investigated the relative contributions of coherent backscatter and shadow hiding opposition effects based on WAC images and, similar to [3], find that the total strength of the opposition effect is inversely correlated with albedo.

The landing of a spacecraft on the lunar surface can change the physical properties of the regolith [5], e.g., by compacting the very porous lunar regolith.

2. Methods

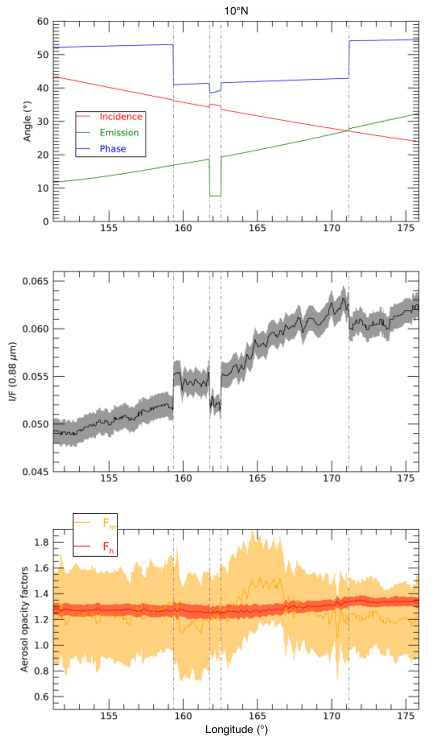

Our method consists of three main steps. Firstly, the WAC or NAC EDR images are downloaded from the PDS and processed with ISIS3 [6]. This process includes calibration and map projection. The NAC images are mapped to a common resolution of 1.6 m/pixel and the WAC images are mapped to a resolution of 400 m/pixel. The sub-solar and sub-spacecraft points are extracted using the campt command in ISIS3.

Secondly, suitable images are co-registered in MATLAB to a common reference image and we calculate the incidence, emission, and phase angles based on the trajectory of the LRO, the sub-solar point, and either the GLD100 [7] in the case of WAC images or a Shape from Shading Digital Elevation Model [8] in the case of NAC images. Due to its large field of view, the phase angle changes significantly within one WAC image. For NAC images the emission angle can be assumed as constant for our region of interest.

Thirdly, we employ the NUTS sampler of pymc3 [9] to infer the posterior density of the parameters of the Hapke model [1] given the data. This Bayesian inference technique [10] also provides us with information about the respective uncertainties. Because several parameters of the Hapke model have a similar influence on the total reflectance, we limit our analysis to three parameters, namely, the single scattering albedo (w), the amplitude of the shadow hiding opposition effect (BS0), and the surface roughness (θb).

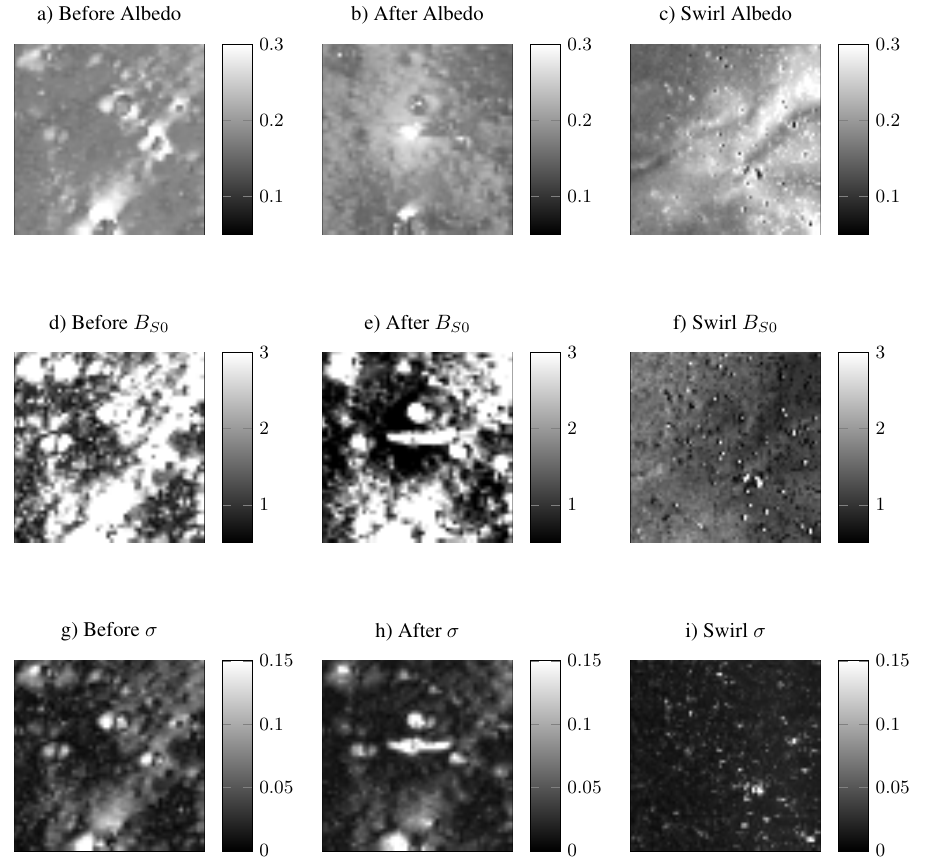

3. Results

For the landing site of Chang’e 5, we selected and co-registered 19 LROC NAC images, 8 before landing and 11 after landing. The phase angles range from approximately 45 degrees to nearly 90 degrees. For the Reiner Gamma swirl, we selected and coregistered 9 LROC WAC images and selected the wavelength channel at 605 nm. All outcrops of the regions of interest are shown in Figure 1. One can see that the image after the landing is overall brighter compared to that before the landing for a similar phase angle. The western part of the Reiner Gamma swirl is also clearly visible by its increased brightness (see Figure 1c). The resulting maps for albedo, shadow hiding amplitude, and mean of the standard deviation of the likelihood function (σ) are shown in Figure 2. The parameter σ describes the quality of the fit of the model and the data and can be interpreted similarly to a root mean squared error. Overall, the albedo increases from before the landing to after the landing, and BS0 decreases around the rover landing site. Very high values of BS0 coincide with shadows of the rover or craters and also correlate with high values of σ. Values with a σ value above 0.07 are labeled as invalid and are, therefore, omitted for future analysis. Pixels with an albedo larger than 0.21 have been labeled as on-swirl or landing-site. The histograms of the BS0 values are shown in Figure 3. They show that the landing site and on-swirl pixels show a significantly weaker shadow hiding effect than the surrounding surface.

Figure 1: Images of similar phase angle for the landing site before (a) and after (b) the landing of Chang’e 5 as well as for the western part of Reiner Gamma (c).

Figure 2: Maps of Hapke parameters.

Figure 3: Distribution of BS0 for the landing site after the landing and the Reiner Gamma swirl.

4. Conclusion

The landing of the Chang’e 5 rover on the Moon has changed the photometric properties of the surface. The albedo has increased and the shadow hiding opposition effect is less strong such that the phase curve has become flatter. This is generally the case for higher albedos but the reduction is nonetheless significantly even below the value expected for the brighter highlands [3]. Similarly, swirls show a reduced opposition effect. A physical explanation could be that the porosity of the regolith is reduced by fast-streaming gas from the landing rocket jet and from a passing comet, respectively (see [5]).

References

[1] B. Hapke (2012). Theory of reflectance and emittance spectroscopy, Cambridge.

[2] M.S. Robinson et al. (2010). Space science reviews, 150(1):81–124.

[3] H. Sato et al. (2014). JGR Planets, 119(8):1775–1805.

[4] Y.I. Velikodsky et al. (2016). Icarus, 275:1–15.

[5] V.V. Shevchenko (1993). Astronomy Reports, 37:314–319.

[6] J. Laura et al. (2022). URL https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.6329951.

[7] F. Scholten et al. (2012). JGR Planets, 117, E00H17.

[8] A. Grumpe et al. (2014). Advances in Space Research, 53(12):1735–1767.

[9] J. Salvatier et al. (2016). PeerJ Computer Science, 2:e55.

[10] A. Gelman et al. (1995). Bayesian Data Analysis, Chapman and Hall/CRC.

How to cite: Hess, M., Wöhler, C., and Qiao, L.: Photometric Modelling for Chang’e 5 Landing Site and Reiner Gamma Swirl, Europlanet Science Congress 2022, Granada, Spain, 18–23 Sep 2022, EPSC2022-147, https://doi.org/10.5194/epsc2022-147, 2022.

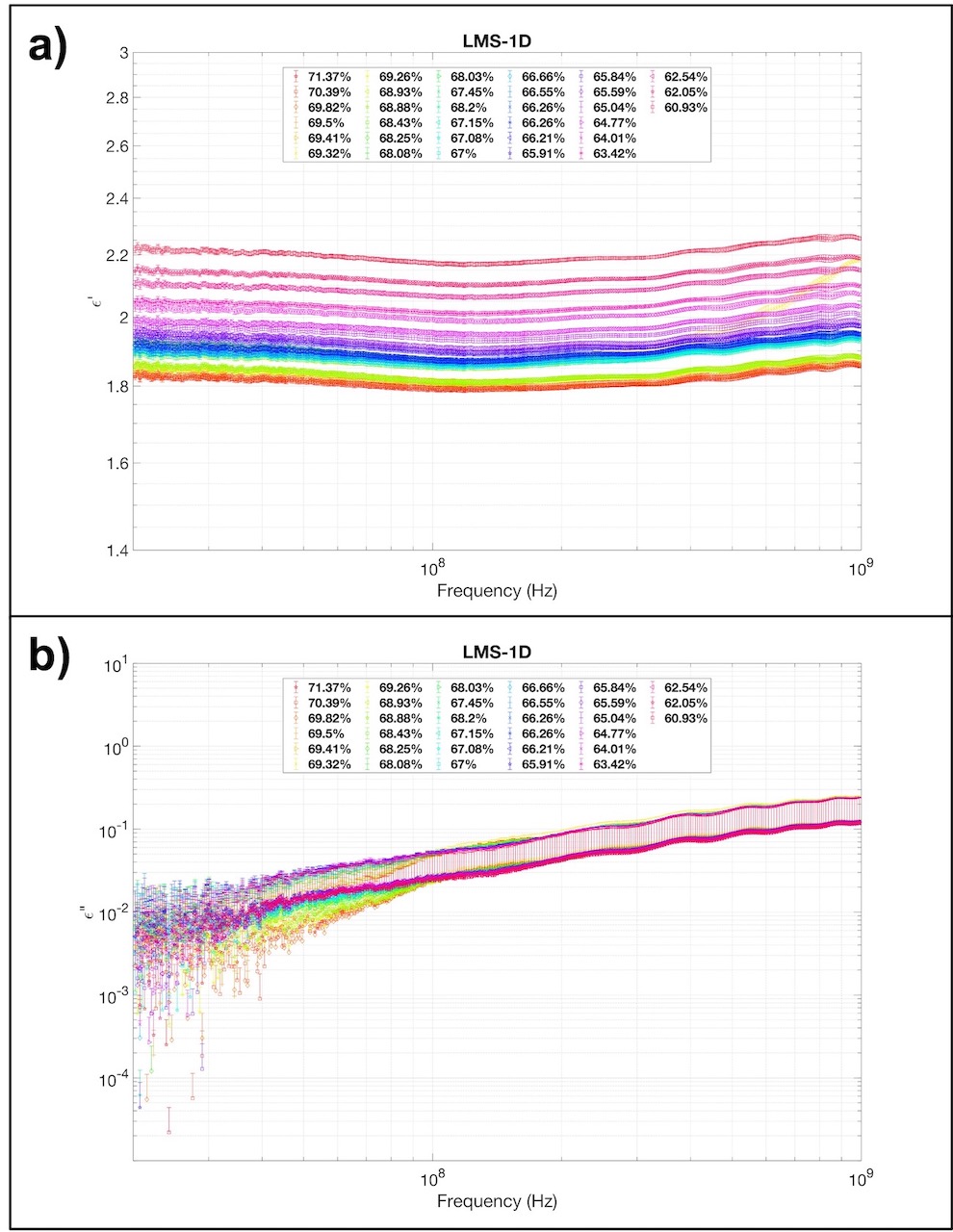

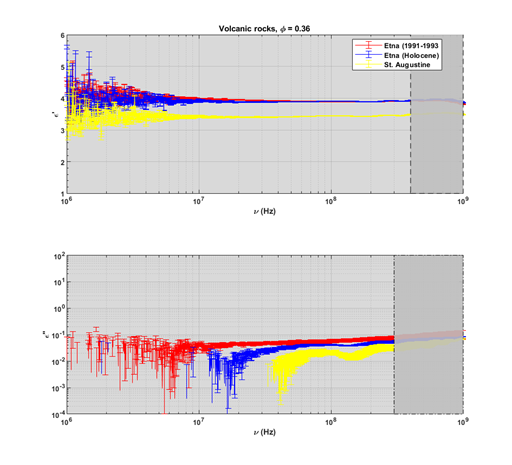

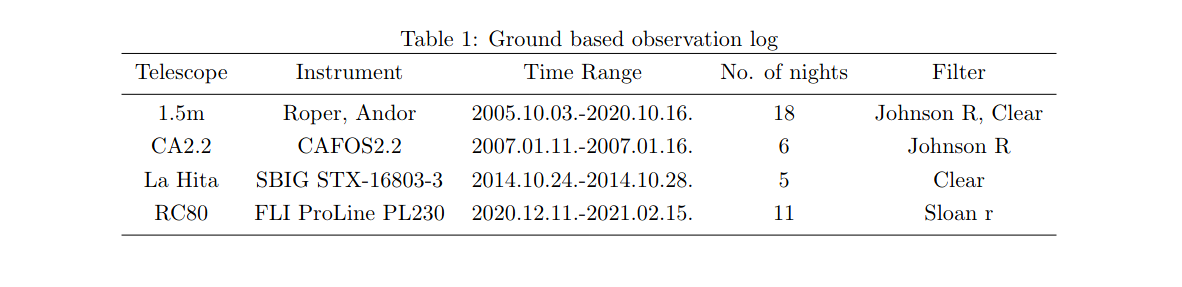

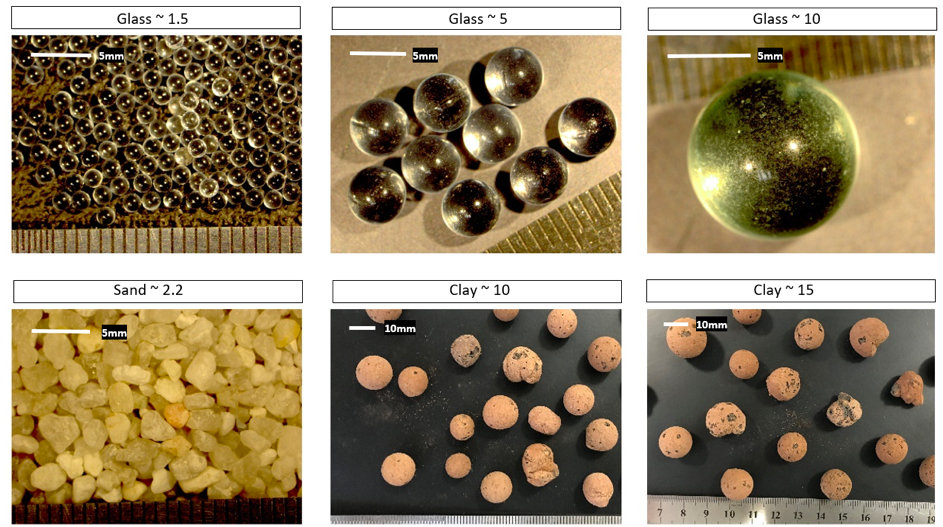

Introduction: Several future missions to the Moon will be devoted to robotic and human explorations in search for ice deposits and other resourses. Ground Penetrating Radar (GPR) is considered a fundamental geophysical instrument to detect water ice inside the regolith and to map the distribution of the volatiles in the lunar polar regions. The success of GPR survey relies on the capability to discriminate between dry and ice-saturated regolith or to detect lenses of relatively pure water ice. To reach this goal an intense laboratory activity is required to characterize the radar response of the lunar regolith as a function of mineralogical composition and different physical conditions (e.g., compactions, temperature, ice content). Here, we present new dielectric measurements of lunar regolith simulants in a broad range of frequencies and for different soil porosities, to improve the interpretation of radar data collected on the Moon. Such measurements have been carried out in the framework of the PrIN INAF “MELODY” (Moon multisEnsor and LabOratory Data analysis) research project, which is devoted to combining past and present lunar data to improve our knowledge on the lunar surface and shallow subsurface properties.

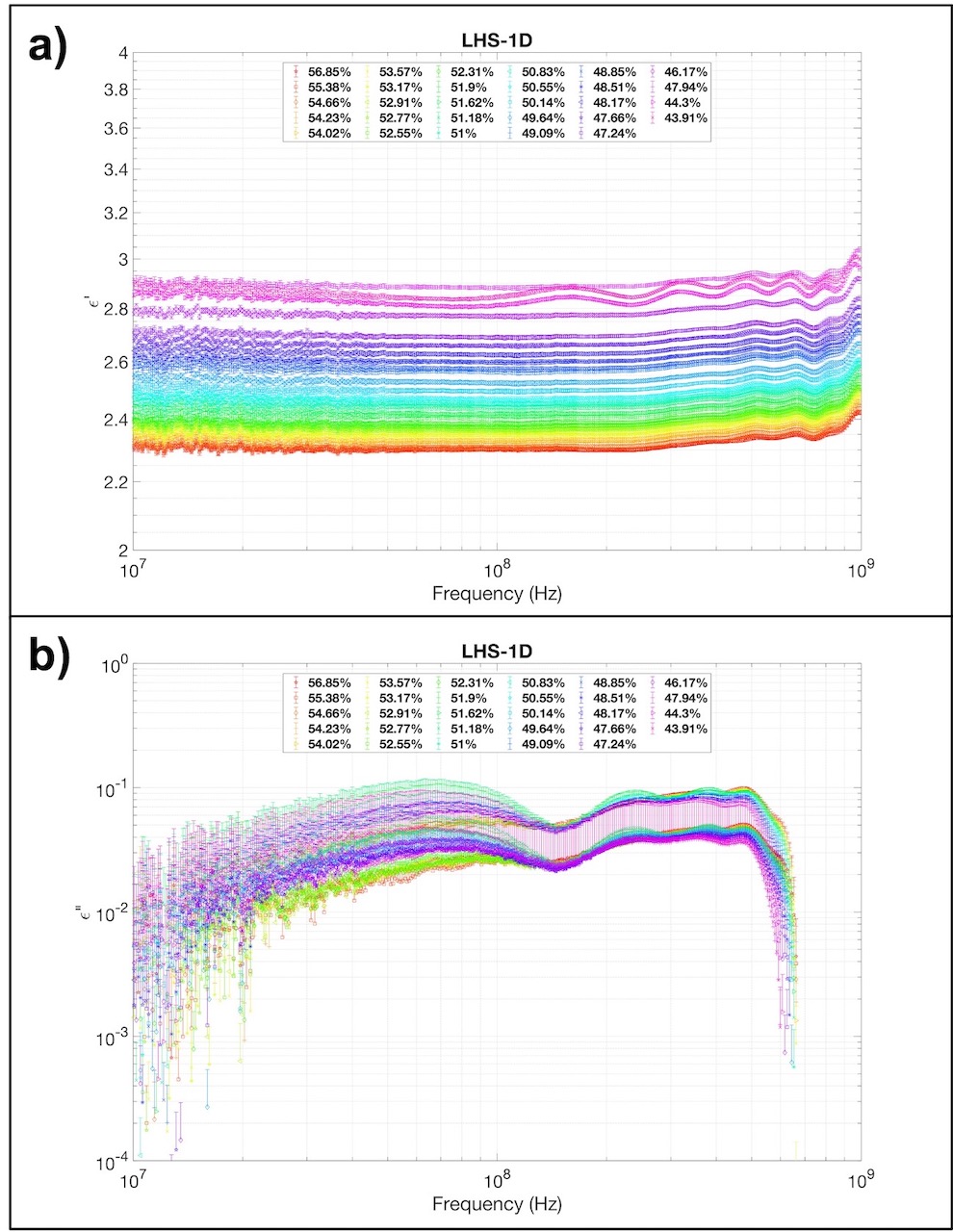

Laboratory measurements: GPR measurements allow one to retrieve signal wave velocity and attenuation in the lunar subsurface [1]. Such parameters are related to complex dielectric permittivity and magnetic permeability, from which some chemical-physical properties of the lunar soil and rocks can be inferred. We apply dielectric spectroscopy techniques for two pairs of commercially available, certified lunar soil analogues (Exolith Lab, 2021a, 2021b) [2, 3] to characterize the radar response of the regolith as a function of mineralogical composition and different physical conditions (e.g., temperature, porosity, and ice content). The investigation of these analogues helps us understand the most reliable lunar soil. Such analogues reproduce the composition of both lunar maria and highlands. The maria analogues are LMS-1D (particle size < 0 – 30 μm) and LMS-1 particle size < 0.04 – 300 μm). The highlands soil simulants are LHS-1D (particle size < 0.04 – 35 μm) and LHS-1 (particle size < 0.04 – 400 μm). The analogues mineralogy are reported in Tab. 1 and Tab. 2.

The measurements are performed at room temperature in the frequency range 100 kHz to 3 GHz, using a Vector Network Analyzer VNA (Agilent E5071C). The VNA ultimately provides the the electromagnetic parameters of the simulant through the Nicholson-Ross-Weir algorithm (NRW) [4]. This method allows one to retrieve both complex dielectric permittivity and magnetic permeability; however due to the negligeble magnetic properties of the samples, here only the dielectric permittivity is reported. Measurements are performend with a coaxial probe line characterized by a multiwire shield cage. Regolith analogues were first oven-dried at 105°C for 24 hours to remove residual water; then the samples are inserted in the teflon cage and different compaction are obtained through a vibration plate.

Results and future work: Fig. 1 (a and b) report the real and imaginary parts of the dielectric permittivity as a function of frequency for the Maria simulant having the smallest particle size range. Fig. 2 (a and b) illustrates the same parameters for the highland simulant. Note that for the two samples a different range of compaction is obtained. The real part of permittivity is frequency independent and decreases with increasing porosity because of the air trapped in the pores, as expected. For lunar maria it ranges from 1.8 to 2.2 (𝜙 from 70% to 60%), while the highland simulant shows higher values between 2.3 and 2.9 (𝜙 from 56% to 44%). Re- garding the imaginary part, it does not show a dependency on porosity, while it shows the same trends at every compaction over the frequency range for both simulants. The next step of the project will be the characterization of the dielectric behaviour of the simulants in a broad range of temperatures (200K – 373K).

Acknowledgements: We acknowledge support from the research project: “Moon multisEnsor and LabOratory Data analYsis (MELODY)” (PI: Dr. Federico Tosi), selected in November 2020 in the framework of the PrIN INAF (RIC) 2019 call.

References: [1] Jol, Harry M., ed. Ground penetrating radar theory and applications. elsevier, 2008. [2] Exolith Labs, U. of C.F LMS-1 Lunar Mare Simulant Spec Sheet (2021). [3] Exolith Lab, U. of C.F LHS-1 Lunar Highland Simulant Spec Sheet (2021). [4] Nicolson, A. M., & Ross, G. F. (1970). Measurement of the intrinsic properties of materials by time-domain techniques. IEEE Transactions on instrumentation and measurement, 19(4), 377-382.

Figure 1: Real (a) and Imaginary (b) part of the permittivity as function of frequency of sample LMS-1D at varying compaction.

Figure 2: Real (a) and Imaginary (b) part of the permittivity as function of frequency of sample LHS-1D at varying compaction.

Table 1: Mineralogy of lunar Highlands analogues LHS-1 and LHS-1D.

Table 2: Mineralogy of lunar Maria analogues LMS-1 and LMS-1D

How to cite: Martella, C. H., Cosciotti, B., Lauro, S. E., Mattei, E., Tosi, F., and Pettinelli, E.: Dielectric measurements of lunar soil analogues at different compactions within the Melody project., Europlanet Science Congress 2022, Granada, Spain, 18–23 Sep 2022, EPSC2022-243, https://doi.org/10.5194/epsc2022-243, 2022.

This study investigates the lunar plasma environment when embedded within Earth's magnetotail. We use data from 10 years of tail crossings by the Acceleration, Reconnection, Turbulence, and Electrodynamics of the Moon's Interaction with the Sun (ARTEMIS) spacecraft in orbit around the Moon. We separate the plasma environments by magnetosheath-like, magnetotail lobe-like, and plasma sheet-like conditions. Our findings highlight that the lobe-like plasma is associated with low densities and a strong magnetic field, while the plasma sheet is characterized by higher densities and a weaker magnetic field. These regions are flanked by the fast, predominantly tailward flows of the terrestrial magnetosheath. During a single lunar crossing, however, the magnetotail displays a wide range of variability, with transient features—including reconnection events—intermixed between periods of lobe-like or sheet-like conditions. We compare and contrast the Moon's local magnetotail plasma to the environments near various outer-planet moons. In doing so, we find that properties of the ambient lunar plasma are, at times, unique to the terrestrial magnetotail, while at others, may resemble those near the Jovian, Saturnian, and Neptunian moons. These findings highlight the complementary role of the ARTEMIS mission in providing a deeper understanding of the plasma interactions of the outer-planet moons.

How to cite: Liuzzo, L., Poppe, A., and Halekas, J.: A statistical study of the Moon's magnetotail plasma environment, Europlanet Science Congress 2022, Granada, Spain, 18–23 Sep 2022, EPSC2022-291, https://doi.org/10.5194/epsc2022-291, 2022.

Introduction:

Analyses of samples returned by the Apollo Program have provided fundamental insights into the origin-history of the Earth-Moon system and how planets and solar systems work. Several special samples that were collected or preserved in unique containers or environments (e.g., Core Sample Vacuum Container (CSVC), frozen samples) have remained unexamined by standard or advanced analytical approaches. The Apollo Next Generation Sample Analysis (ANGSA) initiative was designed to examine a subset of these samples. The initiative was purposely designed to function as a participating scientist program for these samples, and as a preparation for new sample return missions from the Moon (e.g., Artemis) with processing, preliminary examination (PE), and analyses utilizing new and advanced technologies, lunar mission observations, and post-Apollo science concepts. ANGSA links the first generations of lunar explorers (Apollo) with future generations of lunar explorers (Artemis) [1-4].

Progress and Results:

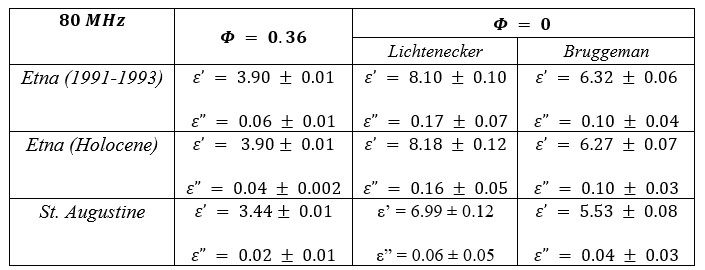

Teamwork for gas extraction from CSVC 73001: To extract any potential gas phase from the CSVC, the European Space Agency (ESA) designed, built, tested, and delivered to JSC a CSVC piercing tool. To collect-store the gas phase, WUStL designed, built, and delivered to JSC a gas manifold system. Together these tools were used to open and sample the CSVC. Preliminary analyses of these gases are being carried out at UNM (Z. Sharp) and WUStL (R. Parai), which will determine whether a lunar component can be detected in the gas.

Extrusion of 73001: Following extraction of gas, the lower part of the double drive tube (73001) was imaged (µXCT, multi-spectral imaging), extruded, dissected, sieved, and examined (Pass 1 and 2). Pass 3 will remain unsieved and will be a target for PE by early career ANGSA scientists-engineers. ANGSA team members participated in the PE of 73002.

Frozen samples: The cold curation facility for processing Apollo 17 frozen samples was approved in mid-December 2021. These samples were processed and allocated in early 2022. Studies are advancing to define differences in preservation of (a) volatiles between frozen and unfrozen samples; (b) thermoluminescence kinetics in lunar samples [e.g., 5]; and (c) chronology.

Stratigraphy of 73001-73002: The stratigraphy of the double drive tube has been examined by multiple approaches. For 73001-73002, the stratigraphy was documented by µXCT imaging [6], reflectance properties [7,8], IS/FeO [8], major, minor, and trace element geochemistry [9,10], grain size/modal proportions [8,11,12], and continuous thin sections [13].

µXCT imaging of lithic fragments: Lithic fragments >4 mm in size were removed from the double drive tube during sampling passes 1-2 (73001-73002); from unsieved Pass 3 > 1cm fragments were removed. µXCT images of hundreds of these lithic fragments were produced. Fragments include a variety of breccias (some with a significant number of spherical glasses), high-Ti basalts with different cooling histories, a variety of “lower-Ti” basalts, and unique lithologies presumably derived from the South Massif. The ANGSA lithic analysis group is carrying out collaborative studies of these fragments [6,14].

Less than 1mm lithic fragments: During processing of Passes 1 and 2 from the double drive tube, samples were sieved into > 1 mm and < 1 mm size fractions. The < 1 mm size fractions were further sieved into 1000-500, 500-250, 250-150, 150-90, 90-20, and <20µm size fractions for selected intervals. In addition to determining modes of each size fraction within the stratigraphy, lithic fragments were also classified and documented. Impact melt rocks and breccias were abundant. Igneous lithologies include ferroan anorthosites, Mg-suite, “felsites”, low-Ti basalts, pyroclastic glasses, and a variety of high-Ti basalts [11,12,15]. Observations (e.g., volatiles, stable isotopes, organics, cosmogenic radionuclides, space weathering) were placed within the context of core stratigraphy [e.g., 16-21].

References: [1] Shearer et al. (2020) 51st LPSC abst.#1181 [2] Shearer (2008) Presentation to CAPTEM. [3] Shearer et al. (2019) 50th LPSC abst. #1412. [4] G. Lofgren (2007) personal communication. [5] Sehlke et al (2022) 53rd LPSC abst. #1267.[6] Zeigler et al. (2022) 53rd LPSC abst.#2890. [7] Sun et al. (2022) 53rd LPSC abst. #1890. [8] Morris et al. (2022) 53rd LPSC abst. #1849. [9] Neuman et al. (2022) 53rd LPSC abst.#1389. [10] Valenciano et al. (2022) 53rd LPSC abst.#2869. [11] Simon et al. (2022) 53rd LPSC abst.#2211. [12] Cato et al. (2022) 53rd LPSC abst.#2215. [13] Bell et al. (2022) 53rd LPSC abst.#1947. [14] Yen et al (2022) 53rd LPSC abst.#1547. [15] Valencia et al. (2022) 53rd LPSC abst#2608. [16] Cano et al. (2021) AGU Fall Meeting abst.; [17] Gargano et al. (2022) 53rd LPSC abst#2450 . [18] Recchuiti et al (2022) 53rd LPSC abst.#2193. [19] Elsila et al. (2022) 53rd LPSC abst.# 1212. [20] Welten et al. (2022) 53rd LPSC abst.#2389. [21] McFadden et al. (2022) 53rd LPSC abst. #1539.

How to cite: Shearer, C. and Zeigler, R. and the ANGSA Science Team: Using an analog lunar sample return mission to grow a lunar sample community and prepare for human return to the Moon’s surface. An update on the progress of the ANGSA initiative., Europlanet Science Congress 2022, Granada, Spain, 18–23 Sep 2022, EPSC2022-747, https://doi.org/10.5194/epsc2022-747, 2022.

- Introduction

When solar wind hits the lunar surface, a fraction of it is reflected back from the Moon instead of being absorbed by its surface. Evidence of neutral hydrogen atoms [1] and solar wind protons [2] being reflected from the surface are provided by numerous studies; however, no measurements of negative ions have been done so far. It is unknown whether or not a significant negative ion population exists near the lunar surface. The Negative Ions at the Lunar Surface (NILS) instrument, the first-ever dedicated negative ion instrument flown beyond the Earth, will address this question. NILS is being developed at the Swedish Institute for Space Physics for the Chinese Chang’E-6 sample return mission. Chang’E-6 is expected to launch in 2024 and will soft-land on the lunar far-side at approximately 41°S and 180°E. NILS will operate at least 30 minutes after the landing to achieve its main science objective. NILS operations will end with the lift-off of the sample return module.

- Main science objective

Negative ions are a not yet observed plasma component at the Moon. NILS’s main objective is to detect negative ions emitted from the lunar surface as a result of the interaction with solar wind and establish the upper limits for their fluxes. That requires NILS to distinguish and resolve the energy distributions of scattered H- and sputtered lunar negative ions, as well as to coarsely resolve different mass groups. The overarching scientific question is to estimate the importance of negative ions for space-surface interactions and environments of planetary bodies with surface-bound exospheres.

- Instrument design

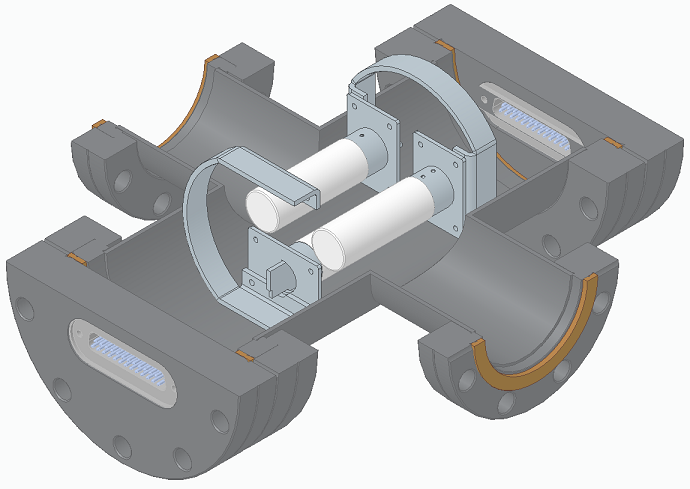

NILS is the 9th generation of the SWIM family [3], a series of compact, adaptive, and capable mass spectrometers analysing ions, electrons or energetic neutral atoms at the sub-keV energy range. NILS combines a compact electrostatic analyser and a time-of-flight cell to measure the energy per charge and the mass per charge of incident ions. An additional deflection system consisting of two cylindrical electrodes allows for a one-dimensional 160° scanning of the viewing direction. NILS instantaneously records negative ions and electrons from a single direction and requires electrostatic scanning to change the viewing direction. Negative ions and electrons can be separated by an electron suppression system placed between the deflection system and the first-order focusing 127° long cylindrical electrostatic analyser. The latter is equipped with micro serrations on the outer electrode to maximize suppression of UV photons and scattered particles.

Prior to entering the time-of-flight cell, ions are post-accelerated by a -400V potential improving the sensor detection efficiency. The time-of-flight start signal is generated by a channel electron multiplier, which detects the secondary electrons generated when that particle is interacting at grazing incidence with a tungsten single crystal start surface. After the reflection on the tungsten surface, the particle travels to a stop surface, where a second secondary electron is generated that then subsequently is detected by a second channel electron multiplier, providing the time-of-flight stop signal. The time difference between the start and stop signals combined with the energy setting of the electrostatic analyser allows determining the mass per charge of the particle.

- References

[1] M. Wieser, S. Barabash, Y. Futaana, M. Holmström, A. Bhardwaj, R. Sridharan, M. B. Dhanya, A. Schaufelberger, P. Wurz, and K. Asamura. First observation of a mini-magnetosphere above a lunar magnetic anomaly using energetic neutral atoms. Geophys. Res. Lett., 37(5), 03 2010.

[2] Y. Saito, S. Yokota, T. Tanaka, K. Asamura, M. N. Nishino, M. Fujimoto, H. Tsunakawa, H. Shibuya, M. Matsushima, H. Shimizu, F. Takahashi, T. Mukai, and T. Terasawa. Solar wind proton reflection at the lunar surface: Low energy ion measurement by map-pace onboard selene (kaguya). Geophys. Res. Lett., 35, 12 2008.

[3] M. Wieser and S. Barabash. A family for miniature, easily reconfigurable particle sensors for space plasma measurements. Journal of Geophysical Research: Space Physics, 2016