- 1Universität Münster, Institut für Planetologie, Münster, Germany (iqbalw@uni-muenster.de)

- 2Department of Earth, Environmental and Planetary Sciences, Brown University, Providence, RI, 02912, USA

- 3School of Earth and Space Exploration, Arizona State University, Tempe, AZ, USA

- 4University of Bern, Switzerland

- 5Lunar and Planetary Institute, USRA, Houston TX, USA

- 6Apollo 15 Commander

Introduction: The topography of a landing region is a critical factor in the operational safety and planning of human extravehicular activities (EVAs). Consequently, digital terrain models (DTMs) and derived slope maps are employed to impose constraints on proposed EVA paths with minimal slopes and elevation discrepancies. It is clear that there are technical constraints associated with the use and operation of equipment and tools, such as suits and instrument carts, and astronaut walking trafficibility. While these constraints have been improved over the years, it is also important to consider the observational, physiological, and psychological experiences and constraints of astronauts when planning successful EVAs. This study examined Apollo astronaut reports as well as audio and video recordings to ascertain the experience and performance of the astronauts in relation to the topography and slopes encountered during their EVAs.

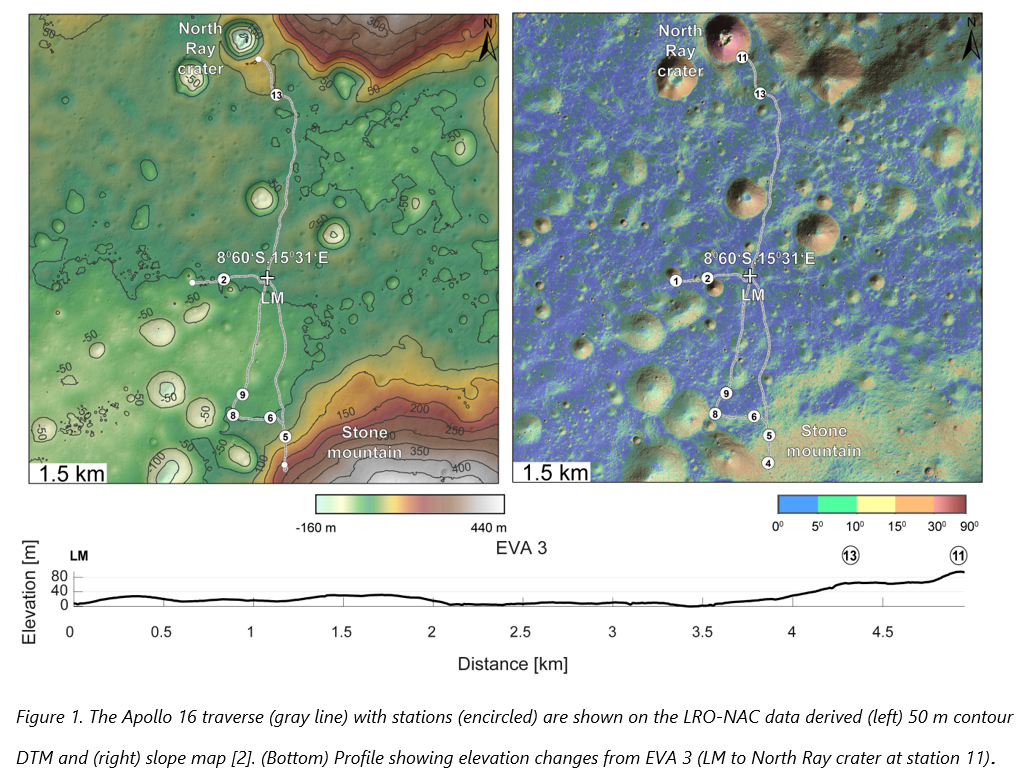

Data and Methods: We conducted an analysis of the elevations and slopes along the traverses of the Apollo landing sites, utilizing the Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter (LRO) Narrow Angle Camera (NAC) derived Digital Terrain Model (DTM) with a 2-m pixel resolution and the related slope map with a 6-m baseline [1,2] (Fig. 1). We extracted topographic profiles of each Apollo landing site traverse in ArcGIS Pro and imported them into Matlab for evaluation. The profiles are simplified and vertically exaggerated by a factor of two (Fig. 1).

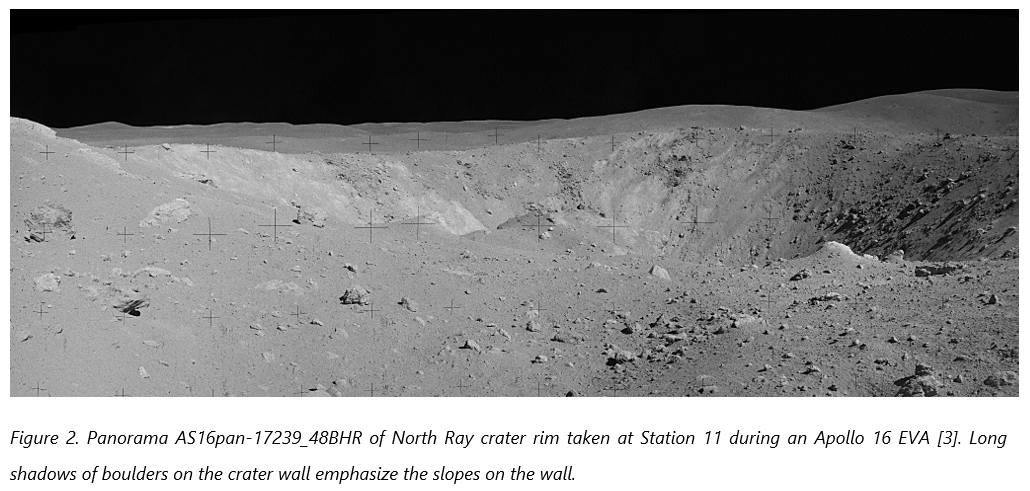

Furthermore, we examined NASA's extensive archive of Apollo mission journals, images (Fig. 2) and video libraries [3], from which we extracted discussions among the astronauts about their experiences dealing with challenging terrain.

Distance Perception: The Apollo astronauts reported difficulty perceiving the distance and size of objects [3]. In addition, incorrect estimates of size and distance have been reported by travelers on Earth, which are attributed to “the absence of objects of comparison” [4]. Astronauts' perceptions are highly influenced by lighting conditions. In conditions with low sun angles, which are prevalent during landing due to the lunar morning landing time, shadows appear longer (Fig. 2) and the terrain appears more rugged. [5].

Slopes Perception: The Center of Lunar Science and Exploration report [6] classifies slopes with inclinations of less than 25° as highly accessible. However, more detailed, quantitative data on the performance of Apollo and Lunokhod provides specific guidelines for use under both Earth-based and lunar conditions [7]. The perception of slope steepness can also be affected by lighting conditions, with boulders on slopes casting particularly long shadows which exaggerate the actual steepness of the slopes. During the Apollo 16 mission, the astronauts standing on the North Ray crater rim (Fig. 2) were unable to see the crater floor. Consequently, they perceived the slope of the wall to be approximately 60°. However, this was in fact less than 30° [3] (Fig. 1).

The lunar surface is characterised by a soft regolith, which presents a challenge for walking on uphill slopes. However, the Moon's gravity is ~1/6th of the Earth, which reduces the risk of astronauts sliding downhill [3]. In their own accounts, astronauts have noted that they relied on their center of gravity while walking downhill [3]. Additionally, Apollo astronauts frequently reported the challenge of traversing slopes due to the limited mobility afforded by carrying their tools and samples. This restriction in movement resulted in a longer time needed to complete a traverse [3]. The lunar roving vehicle was introduced to the Apollo 15, 16, and 17 missions to facilitate the exploration of greater distances and steeper slopes by the astronauts.

Future Missions Planning: The 13 Artemis landing sites were selected on ridges and large crater rims at the South Pole in well-illuminated areas with good Earth visibility, and with potential access to the presumably volatile-rich permanently shadowed regions (PSRs) [7]. However, the landing sites are situated in more complex geological terrains, which may necessitate a greater duration of time at individual stations for the completion of tasks. The astronauts climbed up to 150 m during the Apollo missions and walked on slopes of <15°. In contrast, the Artemis landing sites have elevation differences of ~3400 m. The Apollo astronauts traversed near-equatorial regions on relatively smooth surfaces, but perceived them as rough at low sun angles. Near the South Pole, this effect can be more extreme, limiting visibility and mobility during EVA exploration. It is of the utmost importance to prioritize safety measures [6] and to learn from past successful missions in order to optimize success.

[1] Scholten F., et. al. (2012). J. Geophy. Res. Planet 117 (E12), 2156–2202.

[2] Henriksen M. R., et. al. (2017). Icarus 283, 122–137.

[3] Jones E. M., Glover K. (2017). Apollo lunar surface journal. NASA.

[4] Darwin, C, (1835) ch. XV, p 347, ISBN-13 : 978-1787377424

[5] van der Bogert, C. H., et. al. (2022). LPSC 53., # 1347.

[6] Kring, D. A., Durda, D. (2012). LPI. #1694.

[7] Basilevsky, A.T., et al. (2019). Solar System Research, 53, 383-398.

[8] McKay, D.S., et al. (1991). Lunar sourcebook, 285-356.

How to cite: Iqbal, W., Head, J. W., van der Bogert, C. H., Frueh, T., Henriksen, M., Bickel, V., Kring, D., Hiesinger, H., Scott, D. R., and Heyer, T.: Astronaut experiences on the slopes along Apollo EVAs, Europlanet Science Congress 2024, Berlin, Germany, 8–13 Sep 2024, EPSC2024-196, https://doi.org/10.5194/epsc2024-196, 2024.