- 1California Institute of Technology, Planetary Science, United States of America (mcamarca@caltech.edu)

- 2Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory, USA

- 3NASA Goddard Space Flight Center, USA

- 4Space Telescope Science Institute, USA

- 5Jet Propulsion Laboratory, USA

- 6Southwest Research Institute, San Antonio, TX, USA

- 7Space and Plasma Physics, KTH Royal Institute of Technology, Stockholm, Sweden

Background:

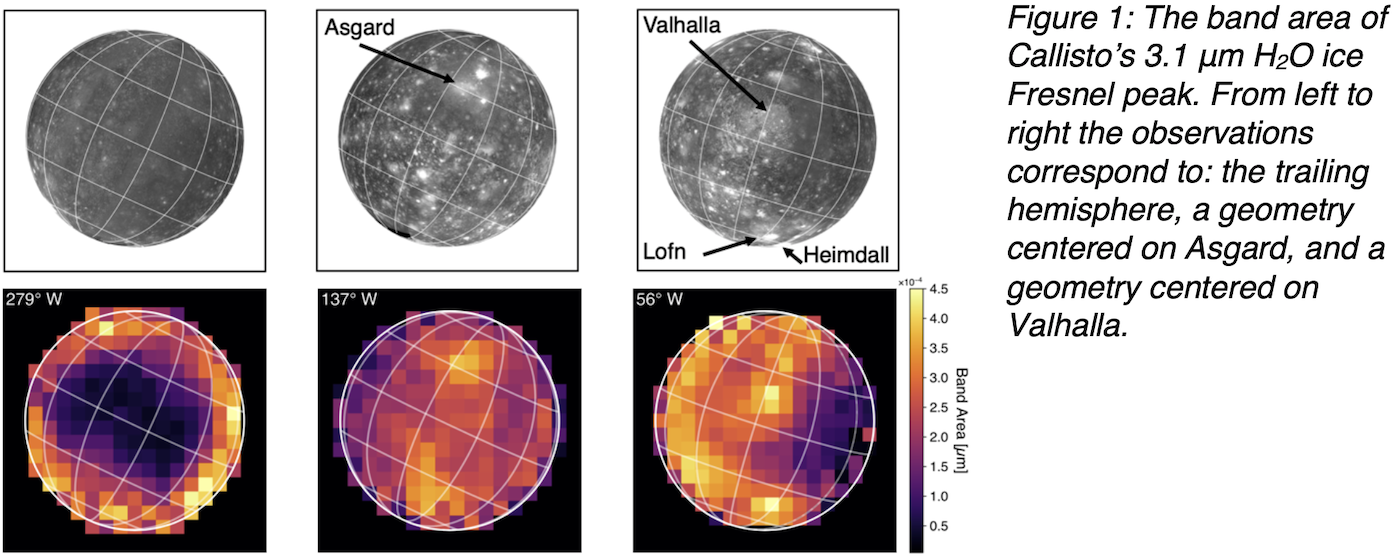

As though it were frozen in time, Jupiter’s moon Callisto has seemingly done little more than collect and degrade impact craters.1 This contrasts with other big icy moons in the solar system (e.g., Ganymede, Titan, Europa), which bear evidence for either past or present endogenic geologic activity. As such, by virtue of its ancient surface (>4 gyr old2), Callisto serves as a template for understanding how an icy, airless body evolves under the near exclusive control of exogenic processes. At present, the study of H2O ice on Callisto and its sibling moons is motivated by the centrality of ice in feeding surface chemistry and atmospheric processes. For example, H2O is an important precursor molecule in the formation of molecular oxygen, a molecule found in their atmospheres and likely trapped in H2O ice on their surfaces3–8. Additionally, H2O may serve as a host for the highly volatile CO2. Studies of the surface chemistry of the Galilean moons are currently being greatly advanced by JWST. In this work, we present a new global map of Callisto’s 3.1 μm Fresnel peak, as well as updated maps of CO2 and the 4.56 μm feature using a new Valhalla-centered cube.

Methods:

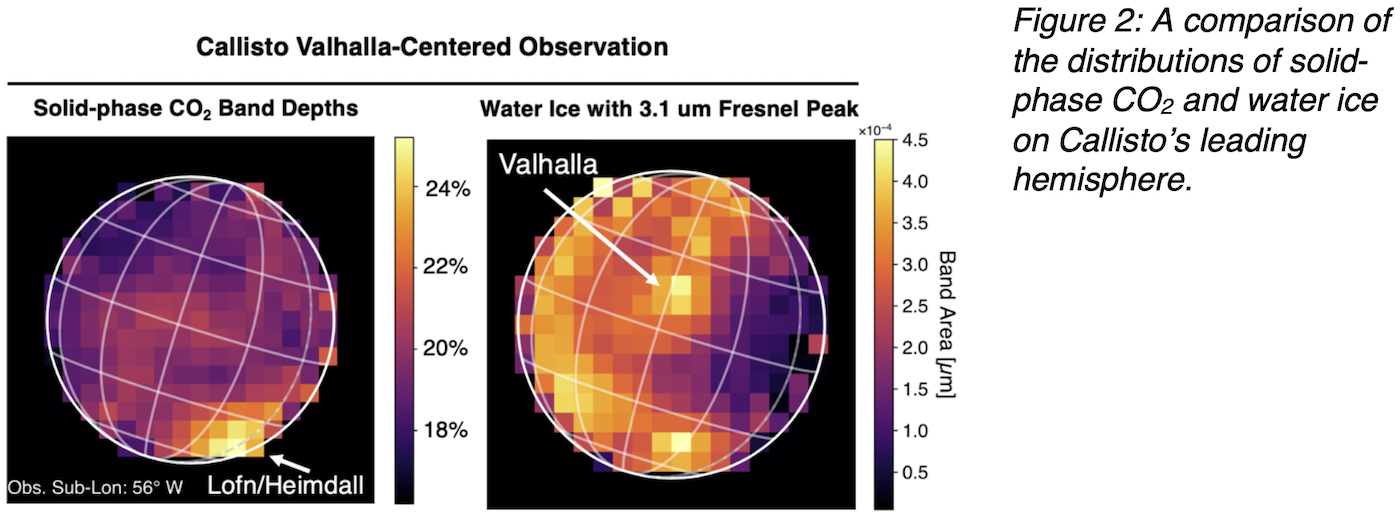

We used the JWST NIRSpec instrument as part of General Observer (GO) program 2060, which observed Callisto on 2022 November 15 and 25 (previously reported9) and 2023 September 20 (reported here, Camarca et al in prep). The 2023 September 20 observation is centered on the Valhalla impact basin. The G395H grating was used in all three observations, spanning 2.85–5.35 μm with an average R ∼ 2700. In this work, we mapped the distribution of both solid-phase and gaseous-phase CO2 at 4.25 μm. We also report band areas of the 3.1 μm H2O ice Fresnel peak, and band depths of the 4.56 μm absorption feature.

Major Findings:

Water Ice: We find that there is a dichotomy between the leading and trailing hemispheres regarding how the strength of the Fresnel peak is distributed on Callisto (Fig 1). On the leading hemisphere, the Fresnel peak correlates well with geologic features (i.e., impacts). We find that Valhalla, Asgard, as well as the region near Lofn/Heimdall bear elevated Fresnel peak band areas, consistent with their higher albedos and ice content as measured by Galileo NIMS1,10. By contrast, the ability of the Fresnel peak to track geology is erased on the trailing hemisphere, and instead exhibits a bull’s eye pattern with lower band areas at low latitudes, similar to what is found on Ganymede 11. We speculate that the Fresnel peak band areas may be suppressed on Callisto’s trailing hemisphere by the exogenic Jovian particle environment, or possibly because H2O ice is feeding the creation of radiolytically produced CO2.

CO2: On the leading hemisphere of Callisto, we find that a region near the Lofn/Heimdall impact terrain is one of Callisto’s most CO2 rich regions (Fig 2). This region is geologically significant on Callisto as the Lofn impact potentially excavated materials from a subsurface slushy/liquid zone12. We also report a new detection of a patchy CO2 atmosphere on the Valhalla-centered observation in which the peak column densities do not match the location of deepest solid-phase band depths near Lofn/Heimdall.

4.56 μm Feature: We find that consistent with past work, the band depths of the 4.56 μm feature are stronger on Callisto’s leading hemisphere than the trailing, including the new Valhalla-centered observation. Additionally, there is evidence for depletion of this feature in center of the Valhalla impact basin.

[1] Moore, J. (2004) In Jupiter: The Planet, Satellites and Magnetosphere, pp. 397–427. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge. [2] Zahnle, K. (1998) Icarus 136, 202–222. [3] Johnson, R. E. (1997) ApJ 480, L79. [4] de Kleer, K. (2023) Planet. Sci. J. 4, 37. [5] Cunningham, N. J. (2015) Icarus 254, 178–189. [6] Spencer and Calvin (2002). AJ 124 [7] Trumbo, S. K. (2021) Planet. Sci. J. 2, 139. [8] Oza, A. V. (2024) Icarus 411, 115944. [9] Cartwright, R. J. (2024) Planet. Sci. J. 5, 60. [10] Hibbitts, C. A. (2000) J. Geophys. Res. 105, 22541–22557. [11] Bockelée-Morvan, D. (2024) A&A 681, A27. [12] Greeley, R. (2001) J. Geophys. Res. 106, 3261–3273.

How to cite: Camarca, M., de Kleer, K., Cartwright, R., Villanueva, G., Holler, B., Hand, K., Glein, C., and Roth, L.: CO2-rich terrain on Callisto’s leading hemisphere and a global dichotomy in Callisto’s H2O ice as seen with JWST, EPSC-DPS Joint Meeting 2025, Helsinki, Finland, 7–12 Sep 2025, EPSC-DPS2025-1046, https://doi.org/10.5194/epsc-dps2025-1046, 2025.