Multiple terms: term1 term2

red apples

returns results with all terms like:

Fructose levels in red and green apples

Precise match in quotes: "term1 term2"

"red apples"

returns results matching exactly like:

Anthocyanin biosynthesis in red apples

Exclude a term with -: term1 -term2

apples -red

returns results containing apples but not red:

Malic acid in green apples

hits for "" in

Network problems

Server timeout

Invalid search term

Too many requests

Empty search term

OPS2

In preparation for the arrival of these missions to the Jupiter system, this session invites contributions from across the planetary science community, with the goal of fostering collaborations that will advance our understanding of topics relevant to the Galilean moons and maximize the scientific return of the missions. This session welcomes presentations concerning laboratory experiments, numerical modeling, terrestrial analog studies, and Earth-based observations (such as those from JWST, ALMA, or HISAKI), as well as analyses of past or ongoing mission data and comparative investigations of icy moons across systems. Topics of interest include the surface geology and composition of the icy Galilean moons, their interior structures and subsurface ocean dynamics, their interactions with Jupiter’s magnetosphere, surface weathering processes, and the formation, structure, and composition of their exospheres. The detection and characterization of potential Europa plumes is also highly relevant.

Additionally, we welcome discussions on the recent Juice Moon-Earth flyby and the Europa Clipper Mars flyby, examining how these events inform upcoming observations at Jupiter. The session will also provide a platform to explore mission objectives, instrumentation, recent developments, and the potential for Juice-Clipper synergistic science, as described by the recent Juice-Clipper Steering Committee report.

Session assets

The JUpiter ICy moons Explorer (JUICE) is the first European Space Agency’s large-class mission of the Cosmic Vision 2015-2025 program. It was launched in April 2023 and is on its way to Jupiter where it will arrive in July 2031, after ca 8 years of cruise.

JUICE aims to explore the conditions that could have led to habitable environments on Jupiter’s icy moons: Europa, Callisto, and Ganymede. Hosting 10 instruments, 1 investigation and 1 radiation monitor, the spacecraft will characterize the structure and environment of the Galilean moons, the Jupiter magnetosphere and atmosphere as well as the various couplings processes at play in this complex planetary system.

Ganymede, the largest moon in the Solar System, is the mission's primary focus due to its potential as a natural laboratory for studying icy worlds and water-worlds. Its role within the Galilean satellite system, along with its unique magnetic and plasma interactions with Jupiter, further elevates its importance.

The nominal mission phase is divided in two phases: a touring part of more than 3 years with 62 equatorial and inclined orbits around Jupiter as well as 36 flybys of the Galilean moons. Late in 2034, the spacecraft will then enter in orbit around Ganymede. Its orbit will initially be elliptical for 5 months, followed by more than 4-month quasi circular orbit at a 500 km altitude and a final 30-day 200 km circular orbit phase.

This presentation will cover the mission's key science objectives, the status of the spacecraft and its new baseline trajectory, the recent Venus Gravity assist, and the upcoming plans for the cruise phase.

How to cite: Vallat, C., Witasse, O., and Altobelli, N. and the JUICE Science Working Team: The ESA’s JUpiter ICy moons Explorer (JUICE) mission updates and future plans, EPSC-DPS Joint Meeting 2025, Helsinki, Finland, 7–13 Sep 2025, EPSC-DPS2025-1976, https://doi.org/10.5194/epsc-dps2025-1976, 2025.

JUICE is the first Large-class mission selected under ESA’s Cosmic Vision 2015-2025 programme. It was launched on 14 April 2023 and is now en route to the Jovian system. Its primary goal is to characterise the conditions that may have given rise to habitable environments on Jupiter’s icy moons, with particular emphasis on Europa, Callisto, and Ganymede. In parallel, JUICE will conduct a multidisciplinary investigation of the Jupiter system as an archetype for gas giants.

To meet these science objectives, the spacecraft carries ten state-of-the-art instruments designed for both remote-sensing and in-situ measurements of Jupiter, its moons, and their shared environment. During the cruise phase, prior to Jupiter arrival in July 2031, each instrument must complete all commissioning and calibration activities to ensure maximum science return from the beginning of the nominal mission.

Opportunities for calibration are limited to week-long payload checkouts performed twice per year and to periods surrounding gravity-assist manoeuvres. These special windows are the first-ever combined Lunar-Earth Gravity Assist in August 2024, followed by Earth fly-bys in 2026 and 2029. An additional about 3-month interval during the cruise phase to Jupiter may also be available for in-situ calibrations in the solar wind.

This contribution outlines the strategy, schedule, and timeline for these critical cruise-phase science operations.

How to cite: Costa, M., Vallat, C., Esquej, P., Andres, R., Valles, R., Belgacem, I., Capuccio, P., Kotsiaros, S., Vervelidou, F., Altobelli, N., and Escalante, A.: JUICE Science Operations during the Cruise Phase, EPSC-DPS Joint Meeting 2025, Helsinki, Finland, 7–13 Sep 2025, EPSC-DPS2025-1981, https://doi.org/10.5194/epsc-dps2025-1981, 2025.

NASA’s Europa Clipper and ESA’s Jupiter Icy Moons Explorer (JUICE) missions are each currently bound to explore the Jupiter system during overlapping time periods in the early 2030s. Europa Clipper is scheduled to arrive in orbit around Jupiter in April 2030, followed by JUICE’s arrival in July 2031. While each mission was designed to pursue its own set of independently compelling science objectives, the temporal and spatial proximity of these two well-instrumented spacecraft presents an unprecedented opportunity to perform coordinated or complementary scientific observations across the Jovian system. The scientific return from such joint activities has the potential to exceed significantly the sum of each mission’s individual efforts.

Recognizing this potential, a JUICE–Clipper Steering Committee (JCSC) was formed jointly by the two mission teams to identify and evaluate possible synergistic science opportunities. This committee includes members from both missions, and it has drawn on science team input from multiple joint workshops, as well as the Science Traceability Matrix developed for the earlier Europa Jupiter System Mission (EJSM) study. The JCSC recently provided a set of recommendations to the two mission teams, describing science themes and observation strategies that could benefit from joint implementation. The recommendations for the orbital (tour) period include time-dependent and space-dependent coordinated measurements of Europa, Ganymede, Callisto, Io, Jupiter’s magnetosphere and atmosphere, the ring system, and small satellites.

The next step is for each mission to consider which of the proposed activities may be realistically implementable within the scope of its mission constraints. Within the Europa Clipper project, which currently focuses on Europa science only, a structured internal assessment is currently underway to evaluate which synergistic science opportunities could potentially align with the mission’s priorities, resources, and operational design.

The Europa Clipper mission, launched in October 2024, is guided by the mission's goal of assessing the habitability of Europa. The mission’s three science objectives are to characterize the ice shell and subsurface structure, characterize the composition and chemistry of the surface and exosphere, and elucidate geological activity and recent surface processes; cross-cutting these is to search for and characterize current activity such as plumes and thermal anomalies. The spacecraft will conduct nearly 50 flybys of Europa at altitudes as low as 25 km over a four-year nominal tour, while also executing opportunistic flybys of Ganymede and Callisto. Europa Clipper carries a sophisticated suite of nine science instruments—spanning imaging, spectroscopy, magnetometry, radar sounding, dust analysis, and mass spectrometry—as well as gravity and radio science supported by the telecommunications system.

Because the mission is complex and constrained by the high-radiation environment of Jupiter, the incorporation of new science activities, even those of high potential value, must be approached with careful evaluation of resource and cost feasibility. Accordingly, Europa Clipper’s internal response to the JCSC recommendations is being developed through a collaborative, phased process led by the Project Scientist.

In the first phase of this process, each of Europa Clipper’s ten Investigation Teams was asked to review the JCSC’s Orbital Report and provide instrument-specific assessments of the scientific value, technical feasibility, and operational implications of the proposed joint observations, and to identify any additional key opportunities that may warrant consideration. These assessments addressed instrument-specific observation opportunities and constraints.

In the second phase, Europa Clipper’s three Objective-based Thematic Working Groups (Interior, Composition, and Geology) were tasked with synthesizing the instrument-level inputs and identifying which opportunities offer the most compelling science return, considering associated constraints. This cross-disciplinary analysis ensures that the evaluation is anchored in integrated science value.

This process also includes coordination with Europa Clipper’s Mission System team, to evaluate the technical and operational feasibility of candidate observations. The Mission System team is advising on resource availability and limitations in areas such as power, spacecraft pointing and slewing capabilities, BDS (bulk data storage) capacity, and downlink availability. Because Europa Clipper operates in a radiation-intense environment and executes carefully choreographed flybys, even small changes to the mission plan could have significant impacts on spacecraft operations, science acquisition, and data return. As such, potential synergistic activities must be thoroughly vetted to ensure they do not compromise the mission’s primary objective or over-extend mission resources.

With this mission-internal assessment, the Project Scientist and Deputy Project Scientists—working in consultation with the JCSC Facilitator—will prepare a recommended package of synergistic observations that Europa Clipper may be able to support. This recommendation will be presented to the full Science Team for discussion and refinement, ensuring that it reflects both broad consensus and careful prioritization. The final recommended set of activities will be shaped by two overarching criteria: (1) scientific significance in the context of Europa Clipper’s science objectives and capabilities, and (2) simplicity and realism of implementation within the mission’s resource envelope.

By the time of the joint EPSC/DPS 2025 meeting, this process is expected to be substantially complete. At the EPSC/DPS 2025 meeting, we will present the results of Europa Clipper’s internal evaluation, including a summary of which synergistic science opportunities have been prioritized for potential implementation. We will also describe the science and operations constraints considered in the decision-making framework, and the next steps that may follow.

This presentation aims to inform the planetary science community of Europa Clipper’s strategy for evaluating and potentially implementing cross-mission science opportunities. It is intended to support transparency and demonstrate the mission’s commitment to maximizing scientific return while preserving its primary goal and the integrity of its three science objectives. This work complements the separate report of the JUICE–Europa Clipper Steering Committee. We note that at present, no formal agreements or commitments exist between NASA and ESA regarding the implementation of joint science activities.

Government support acknowledged. Writing assisted by ChatGPT 4o.

How to cite: Pappalardo, R., Korth, H., Burratti, B., and Choukroun, M.: Assessing Europa Clipper’s Response to JUICE–Clipper Synergistic Science Opportunities in the Jupiter System, EPSC-DPS Joint Meeting 2025, Helsinki, Finland, 7–13 Sep 2025, EPSC-DPS2025-1147, https://doi.org/10.5194/epsc-dps2025-1147, 2025.

Europa Clipper was launched on October 14, 2024 to implement NASA’s first detailed exploration of an ocean world. Europa almost certainly contains a global subsurface ocean where a potentially habitable environment could have persisted for millions if not billions of years. The nominal tour of 4.27 years includes about 50 flybys of Europa, some as close as 25 km. The underlying theme of the mission is to search for the building blocks of life that could provide the foundation for a habitable environment. With the likely existence of other ocean worlds in the Solar System, including Titan, Enceladus, Ganymede, Ceres, and potentially many more in other solar systems, the detailed exploration of Europa takes on prime importance.

The main objectives of the mission are to characterize the ice shell and any subsurface water, including their heterogeneity, ocean properties, and the nature of surface–ice–ocean interactions; understand the habitability of Europa’s ocean through composition and chemistry; and understand the formation of surface features, including sites of recent or current activity, and characterize high science interest localities. A final cross-cutting objective is to search for current activity.

The mission’s objectives will be addressed with an advanced suite of complementary instruments. The remote sensing payload consists of the Europa Ultraviolet Spectrograph (Europa-UVS), Europa Imaging System (EIS), Mapping Imaging Spectrometer for Europa (MISE), Europa Thermal Imaging System (E-THEMIS), and Radar for Europa Assessment and Sounding: Ocean to Near-surface (REASON). The in-situ instruments are the Europa Clipper Magnetometer (ECM), Plasma Instrument for Magnetic Sounding (PIMS), SUrface Dust Analyzer (SUDA), and MAss Spectrometer for Planetary EXploration (MASPEX). Gravity and Radio Science (G/RS) will be achieved using the spacecraft's telecommunication system, and valuable scientific data of the radiation environment will be collected by the engineering sensors comprising the Radiation Monitor (RadMon). All instruments will be operating together, with the remote sensing instruments pointed to nadir and the in-situ instruments pointing in the ram direction. With a total ionizing dose of 2.97 Mrads, one of the challenges of the missions is to protect the instruments’ electronics from damaging radiation. The main mitigation tactic was to encase most of the electronics in a metal vault. Another operational mitigation is to orbit Jupiter rather than Europa, and swoop into the more dangerous environment of high energy particles at Europa only for encounters.

The cruise period is about five and a half years, providing a long period to check out and calibrate the instruments, as well as to optimize the science planning process for the tour. Initial checkouts and activities have been successful, with minor problems corrected. The interplanetary trajectory includes two gravity assists: one at Mars, which occurred on March 1, 2025, and another at Earth, which will occur on December 3, 2026. The Mars flyby provided an opportunity for key calibrations for E-THEMIS; an end-to-end test of REASON; and checkouts of all the telecommunication components necessary for the G/RS experiment. Although all data are not on the ground as of early May, the indications are that these activities were successful. More activities are being planned for the Earth-flyby. Jupiter Orbit Insertion occurs on April 11, 2030, with an initial flyby of Ganymede on October 30, 2030. The first flyby of Europa will occur on March 7, 2031 with a closest approach of just over 200 km.

During most of the period of the Europa Clipper mission, the European Space Agency (ESA) will be operating the highly complementary Jupiter Icy Moons Explorer (JUICE) mission. JUICE will focus on Callisto, Ganymede, and fields and particles in the vicinity of Jupiter. Although only two flybys of Europa will occur as part of the mission, one will happen almost simultaneously with one of Europa Clipper’s flybys. These coordinated flybys will offer an unprecedented opportunity to understand the Jovian system at a very large spatial scale. The two science teams have begun informal collaborations to consider synergistic science opportunities during this key period, as well as during cruise and approach.

Following the success of the efforts established by other missions, the Europa Clipper science team includes a ground-based astronomical observers support group. The purpose of this group is to provide follow-up for transient events; to offer greater temporal and spatial context; and to obtain wavelengths and viewing geometrics not observed by Europa Clipper.

The Europa Clipper team has published articles on the mission, instruments, and engineering systems in an open-access topical collection of the journal Space Science Reviews. The team has begun science observation planning for both nadir and non-nadir periods of the nominal tour to sketch out a Strategic Science Planning Guide, which details the science observation strategy. This presentation will provide any late updates, particularly those involving the recent gravity assist at Mars.

Government support acknowledged.

How to cite: Buratti, B. and the Europa Clipper Science Team: Europa Clipper: An Overview of the Mission, EPSC-DPS Joint Meeting 2025, Helsinki, Finland, 7–13 Sep 2025, EPSC-DPS2025-1031, https://doi.org/10.5194/epsc-dps2025-1031, 2025.

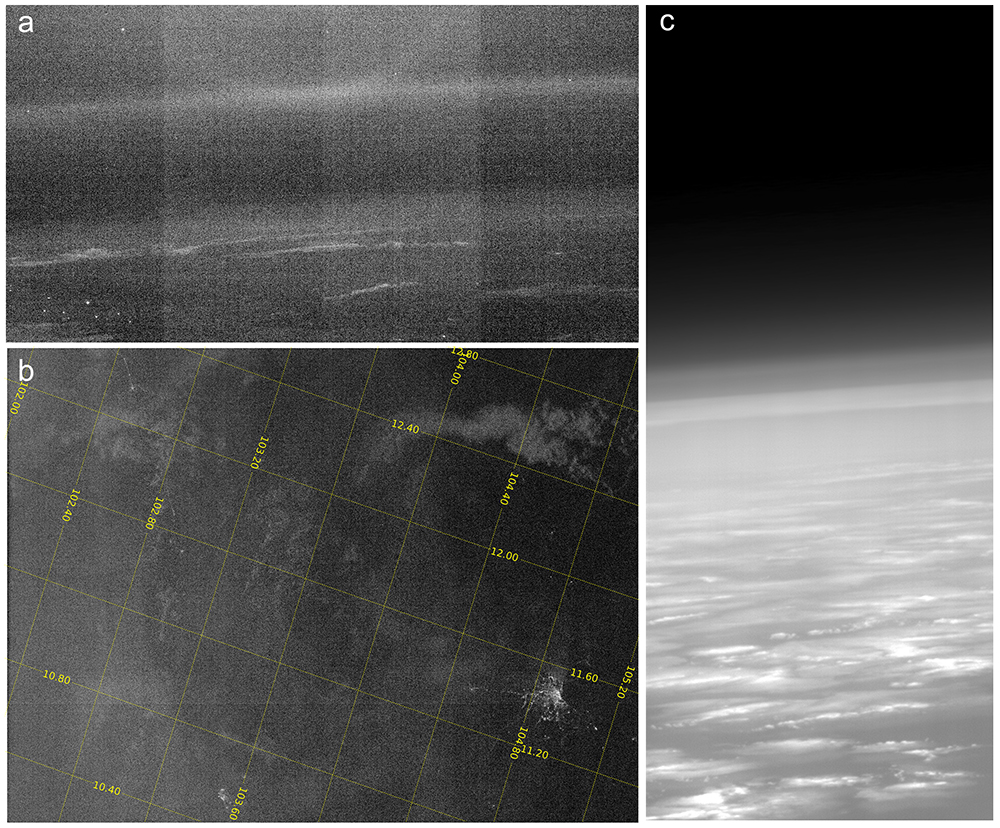

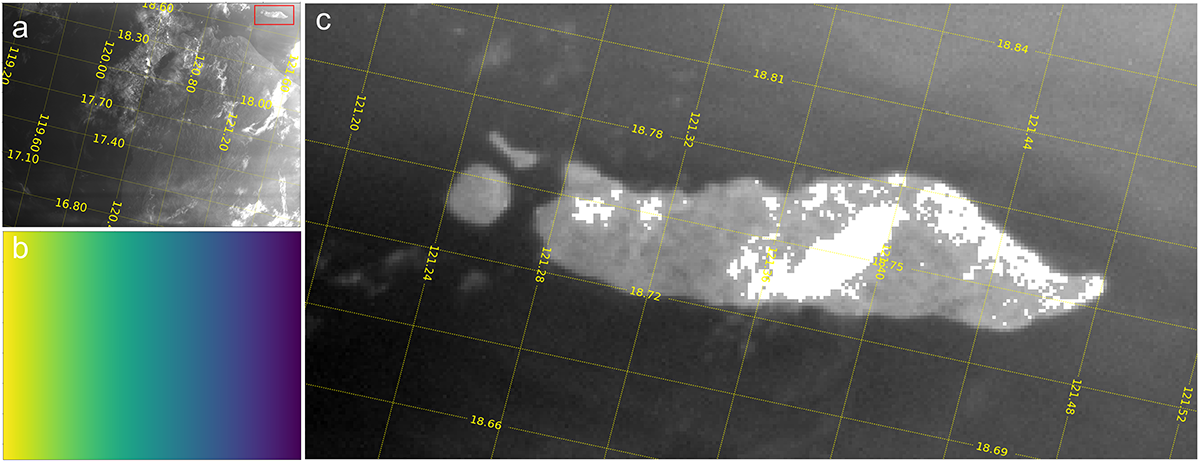

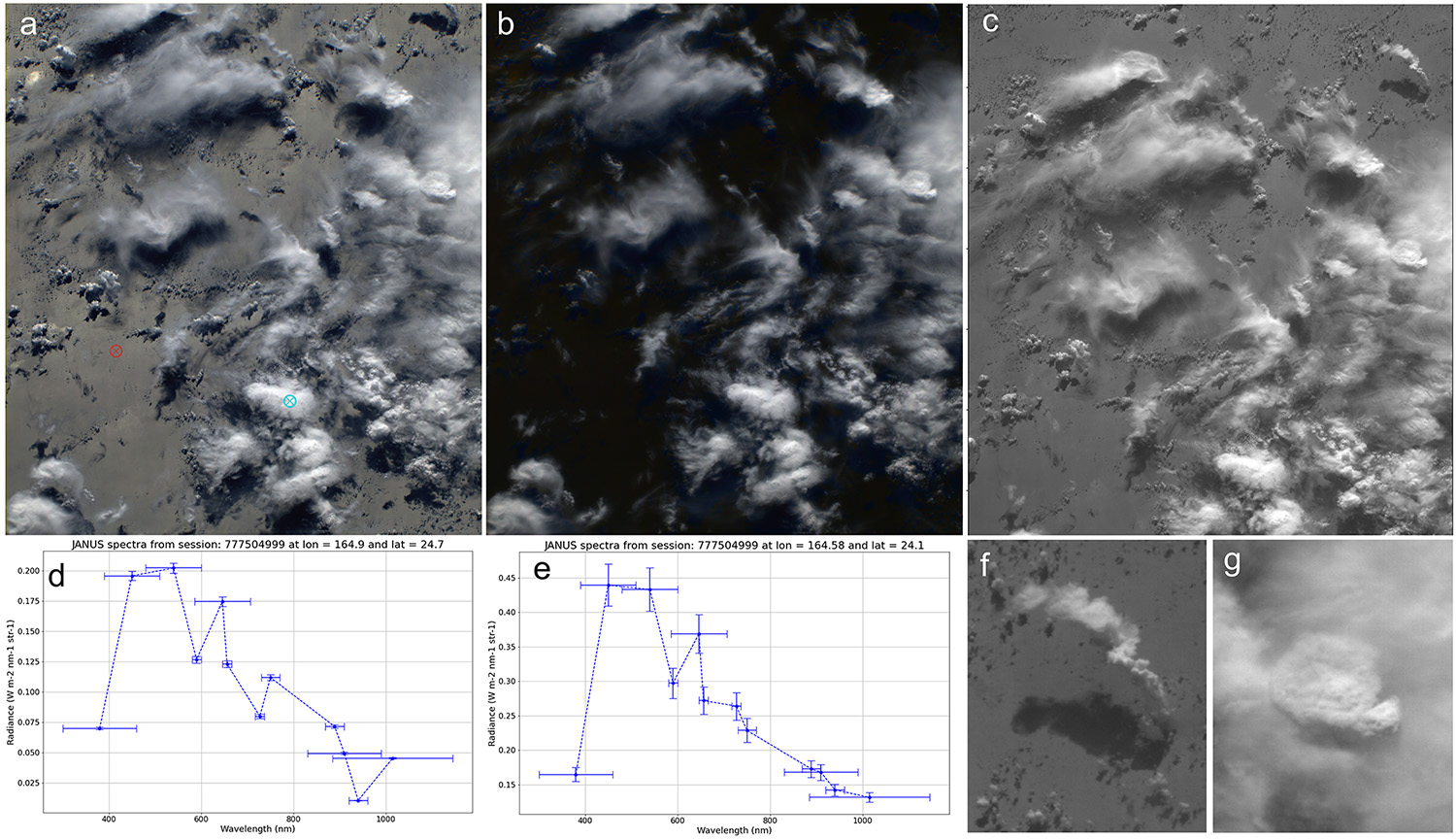

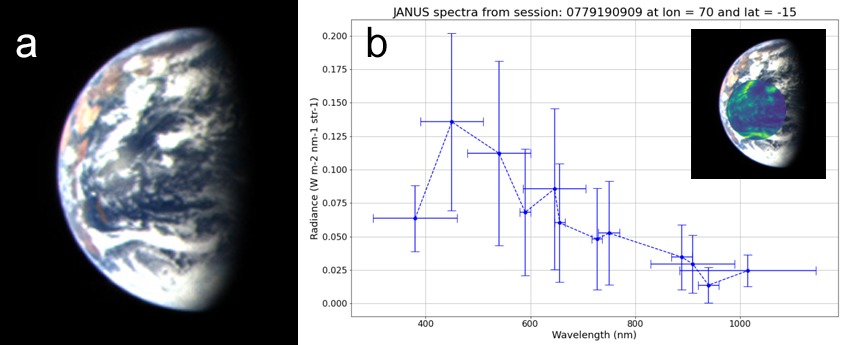

Introduction The JANUS (Jovis, Amorum ac Natorum Undique Scrutator) imaging system [1], onboard ESA’s JUICE mission, had the unique opportunity to observe both Moon and Earth during the Lunar-Earth Gravity Assist (LEGA) maneuver on August 19–20, 2024. This flyby represented the first opportunity to operate JANUS under conditions like those expected in the Jovian system. The JANUS telescope, a modified Ritchey-Chrétien design with a 103.6 mm aperture and 467 mm focal length, uses a Teledyne-e2v CMOS detector and 13 filters spanning 340–1080 nm. During LEGA, the instrument observed the Moon’s dayside, capturing imagery across a wide latitudinal and longitudinal track. Observational planning considered operational constraints, such as filter switching times, data volume limits, and rapid spacecraft motion. The collected data supported performance verification, calibration refinement, and validation of data processing tools, effectively preparing JANUS for its forthcoming scientific operations in the Jovian system. In addition, such a flyby enables us to conduct unique scientific investigations of the Moon thanks to high-resolution and multifilter images acquired.

JANUS Observation of the Moon During the Moon flyby, due to operational constraints, JANUS was switched on 1 hour before the beginning of image acquisition. To ensure thermal stability at the time of observation, the S/C survival heaters were used to bring the telescope to the optimal temperature. Imaging began shortly before crossing the lunar terminator and continued beyond limb crossing to capture stray light. Observations covered latitudes 17°S–16°N and longitudes 107°E–7°W, encompassing prominent lunar features such as the LaPérouse and Langrenus craters, Mare Fecunditatis, Sinus Asperitatis, and the southern portion of Mare Tranquillitatis. Initial imaging used the panchromatic filter with lossless compression, followed by multi-filter sequences (4 to 13 filters) under varying solar incidence angles (90° to 29°), enabling detailed coverage and performance assessment. Among the regions observed by JANUS, our investigation focuses on two specific areas, detailed below.

Langrenus crater: Langrenus is a prominent lunar impact crater located at approximately 8°S, 61°E, on the eastern boundary of Mare Fecunditatis. Measuring ~132 km in diameter and ~2.7 km in depth, it exhibits a well-preserved, terraced rim and steep inner walls, characteristic of complex craters. A central peak structure rises ~1 km above the crater floor, indicative for gravity-driven crater modification. During the LEGA flyby, the JANUS camera acquired high-resolution imagery of Langrenus (~20 m/pixel) using four distinct filters: Blue (450/60 nm), Red (646/60 nm), NIR1 (910/80 nm), and NIR2 (1015/130 nm), as shown in Fig.1. These data support both morphological and spectrophotometric analyses of the crater. A detailed geological map is in preparation to distinguish the geomorphological and structural units across the crater. Langrenus also serves as a stratigraphic window into the adjacent titanium-rich mare basalts. A Digital Terrain Model (DTM) derived from the combination of JANUS imagery and other lunar dataset will enable refined topographic analysis. Complementary spectral analysis is underway to identify the presence of mafic minerals such as olivine and pyroxenes. As illustrated in Fig. 1, the derived RGB composite reveals bluish regions consistent with pyroxene-bearing material, offering valuable insights into the compositional diversity of the site.

Mare Fecunditatis Area: We are conducting a detailed analysis of the boundary between Mare Fecunditatis and Mare Tranquillitatis, focusing on the transition zone between the lunar maria and adjacent highlands. This region was imaged by the JANUS instrument at spatial resolutions ranging from 30 to 60 m/pixel, using various filter sequences. The observations reveal a variety of geological features, including wrinkle ridges, small impact craters, and rounded volcanic domes.

As illustrated in Fig. 2, a representative segment of the Mare Fecunditatis–highland boundary was imaged using five JANUS filters (Violet 380/80 nm, Blue 450/60 nm, Red 646/60 nm, NIR1 910/80 nm, and NIR2 1015/130 nm). From these data, both standard RGB and Clementine-like RGB composites were generated (e.g., R=750/430, G=750/1015, B=430/750). The resulting imagery demonstrates strong consistency with previous mission datasets while offering enhanced spatial resolution for improved geological interpretation.

Ongoing spectral analysis will further investigate compositional variations across the mare–highland interface, with the goal of identifying localized mineralogical concentrations and enhancing our understanding of lunar crustal evolution.

Discussion and future works

The JANUS imaging system, as demonstrated during its observation of the Moon during the LEGA maneuver, has proven its capability to capture high-resolution, multi-filter imagery under conditions similar to those expected in the Jovian system. The ability to observe lunar features across a broad latitudinal and longitudinal range provides a comprehensive dataset for both performance verification and scientific investigations. Detailed analyses of the Langrenus crater and the Mare Fecunditatis region highlight the potential for understanding lunar geological processes, especially in terms of compositional and structural variations. Fresh highlands materials are blue, fresh mare materials are yellowish, and mature mare soils are purplish or reddish. Fresh crater rims appear cyan and due to its color fresher and mature basalt units can be distinguished to their yellowish and reddish color (Fig.2) partly showing sharp geological boundaries. In the next future, we will advance the investigation of JANUS observations and integrate with other lunar datasets, such as topographic and spectral data, will allow for an enhanced interpretation of the lunar surface, enabling insights into the history and evolution of both impact and volcanic processes.

Acknowledgement: JANUS has been funded by the respective Space Agencies: ASI (lead funding agency), DLR, Spanish Research Ministry and the UK Space Agency. Main hardware-provider Companies and Institutes are Leonardo SpA (Prime Industry), DLR-Berlin, CSIC-IAA and Sener. PI and Italian team members acknowledge ASI support in the frame of ASI-INAF agreement n. 2023-6-HH.0. We gratefully acknowledge funding from National Institute of Astrophysics through the INAF - Mini Grant RSN3 RIFTS project (d.d. 5/2022). Part of this work was carried out at the Jet Propulsion Laboratory, California Institute of Technology, under contract with NASA

References [1] Palumbo, P., et al., 2025, SSR. [3] Grasset, O., et al., (2013). PSS, 78, 1-21.

How to cite: Lucchetti, A., Massironi, M., and Gwinner, K. and the JANUS Team: High-Resolution Morphological and Spectrophotometric Analysis of the Moon Using JANUS Observations from the LEGA Flyby, EPSC-DPS Joint Meeting 2025, Helsinki, Finland, 7–13 Sep 2025, EPSC-DPS2025-311, https://doi.org/10.5194/epsc-dps2025-311, 2025.

Please decide on your access

Please use the buttons below to download the supplementary material or to visit the external website where the presentation is linked. Regarding the external link, please note that Copernicus Meetings cannot accept any liability for the content and the website you will visit.

Forward to presentation link

You are going to open an external link to the presentation as indicated by the authors. Copernicus Meetings cannot accept any liability for the content and the website you will visit.

We are sorry, but presentations are only available for users who registered for the conference. Thank you.

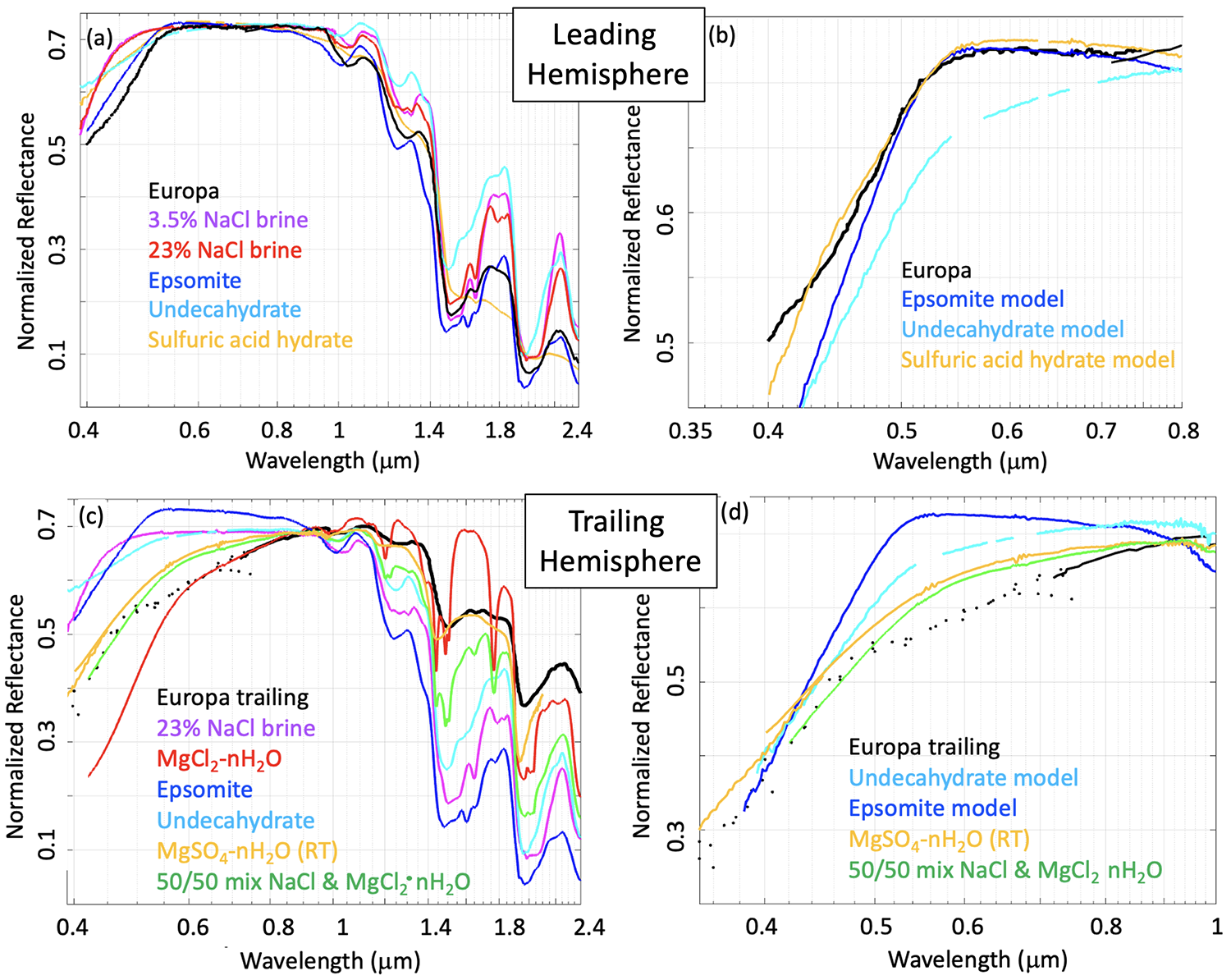

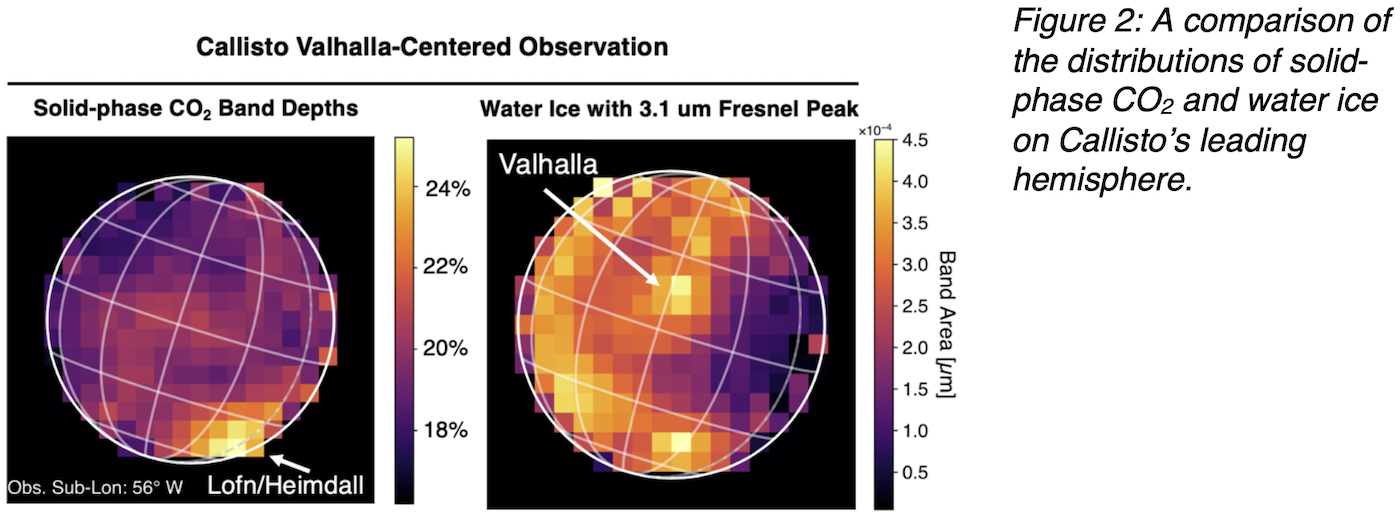

Introduction:

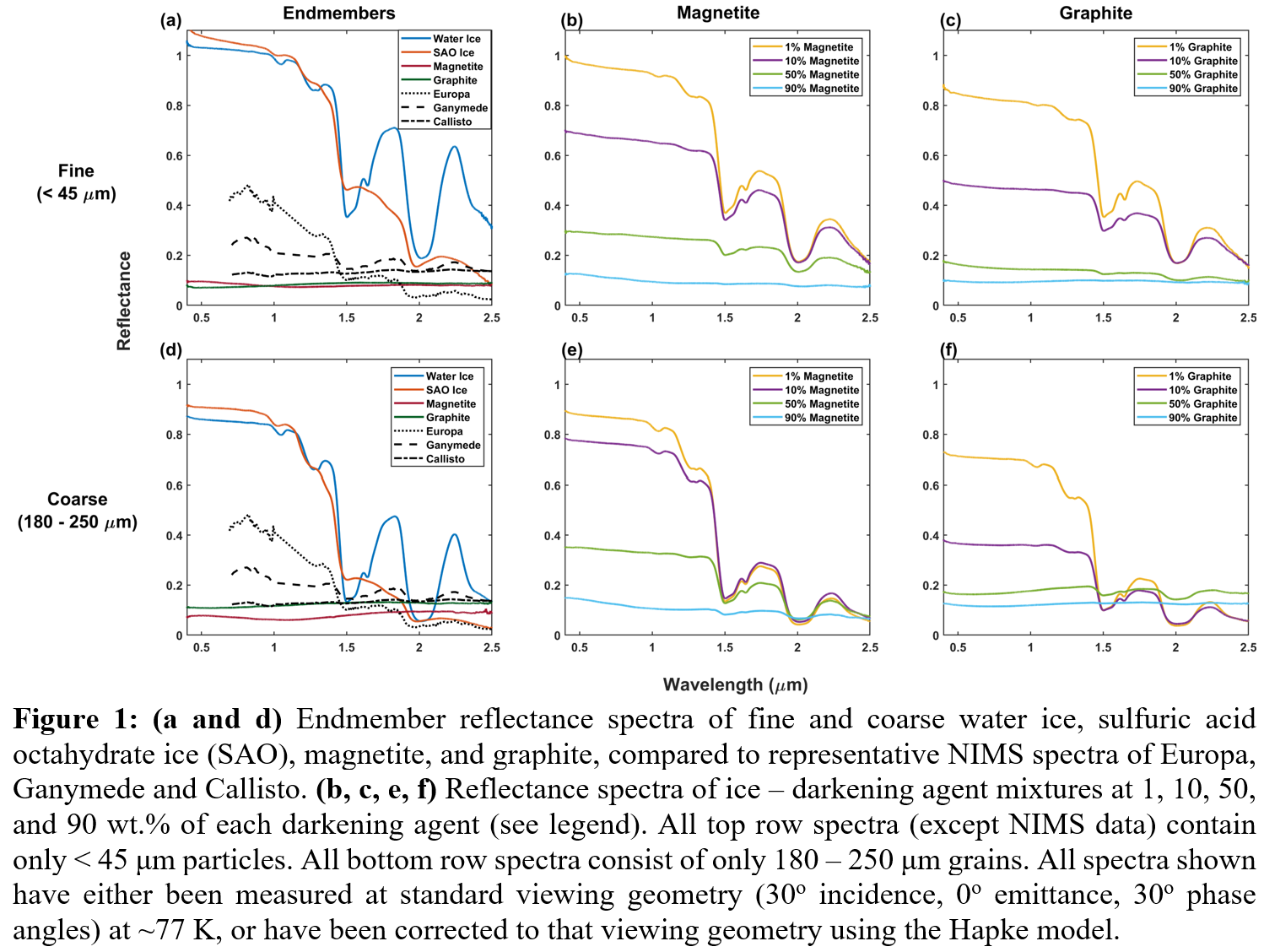

The icy Galilean moons, Europa, Ganymede, and Callisto, have surfaces with visible to near-infrared (VNIR) reflectances that are darker than expected for ices composed of water, acids, and salts. (see Figure 1a, 1d). Past investigations of these moons suggest neutral darkening agents (low reflectance and spectrally featureless materials) may be present. Common darkening agents include Fe- or C-bearing minerals, such as magnetite and graphite, which can be delivered through micrometeorite bombardment, radiolysis of surface species, or endogenic activity [1-3]

Darkening agent abundances are reportedly <20%, ~50%, and ~90% for Europa [4], Ganymede [5,6] and Callisto [7], respectively; however, large uncertainties are present in these estimates. These moons’ surfaces are likely intimately mixed due to space weathering and potential endogenic activity. A few wt.% darkening agent when intimately mixed with bright materials can drastically reduce the overall mixture’s reflectance [8]. Previous darkening agent abundances [4-7] are influenced by more than physically present species. They are sensitive to particle size effects and act as free variables for unknown surface materials. Due to this, our understanding of these moons’ surfaces and therefore the processes happening on and within them may be inaccurate.

This study seeks to provide constraints for magnetite and graphite as darkening agents in mixtures of water and hydrated sulfuric acid ices. The VNIR reflectance spectra of these mixtures are compared to those collected by the Galileo’s Near Infrared Mapping Spectrometer (NIMS) to determine rough abundances needed to achieve sufficient darkening. We additionally compare laboratory measurements with modeled spectra computed via radiative transfer theory [9] to further investigate model limitations.

Results:

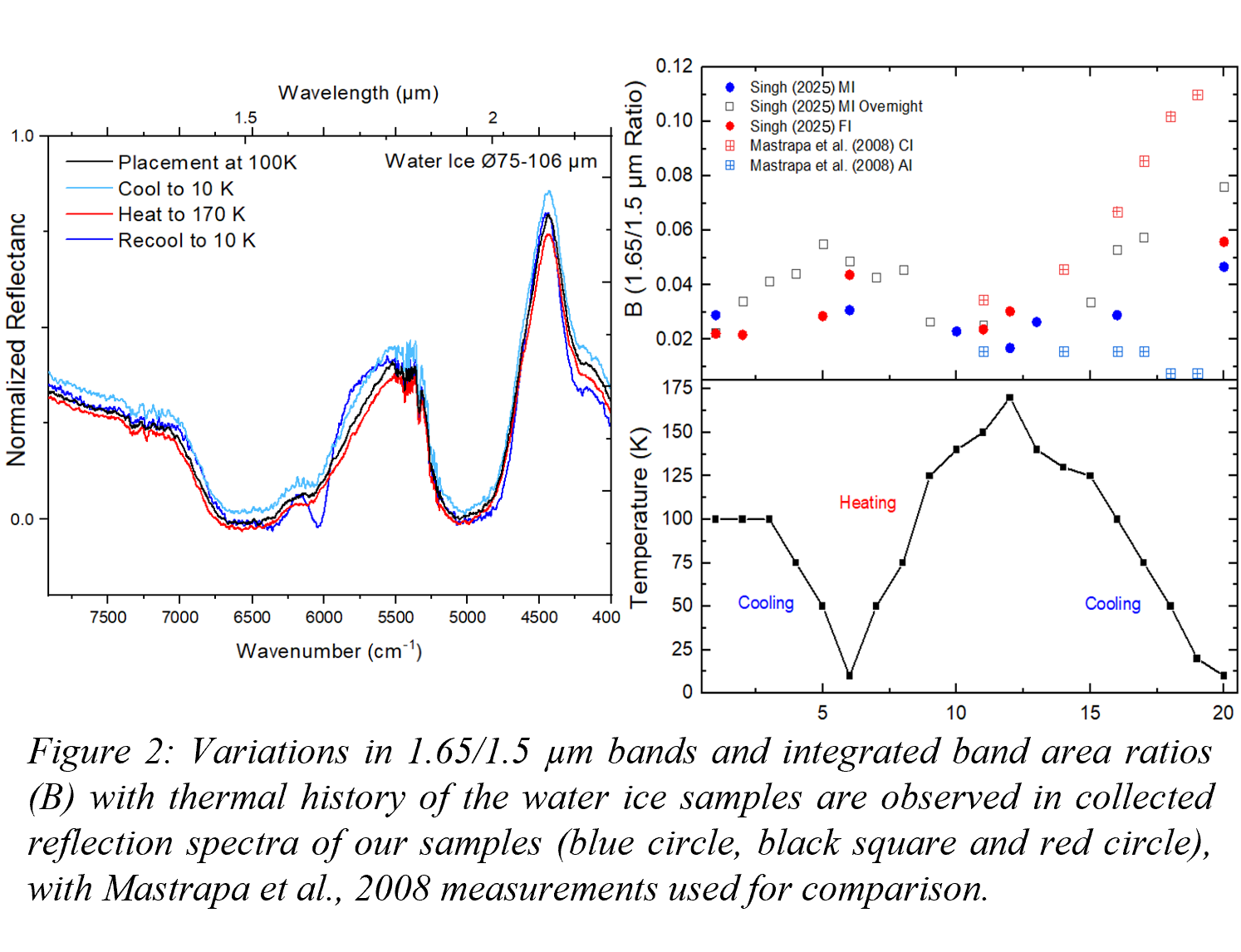

VNIR reflectance spectra for mixtures of sulfuric acid octahydrate ("SAO") ice, water ice, and graphite or magnetite are shown in Figure 1 (b, c, e, f). For each darkening agent, two particle size groups are investigated, fine (<45 μm) and coarse (180 – 250 μm), to probe effects due to particle size variations. Each mixture set investigates darkening agents at 1, 10, 50, and 90 wt.%. Water and SAO ices comprise the remainder of these mixtures equally.

The fine and coarse darkening agent mixtures suggest a few wt.% darkening agents may not cause drastic overall darkening. Darkening by graphite is more efficient than magnetite at similar abundances, with total saturation being achieved at ~50% graphite compared to 90% magnetite. These mixtures are compared to the NIMS reflectance spectra shown in Fig. 1a, 1d to determine rough abundance estimates for the amount needed to match NIMS spectra (see Table 1, which displays the best matching abundance value).

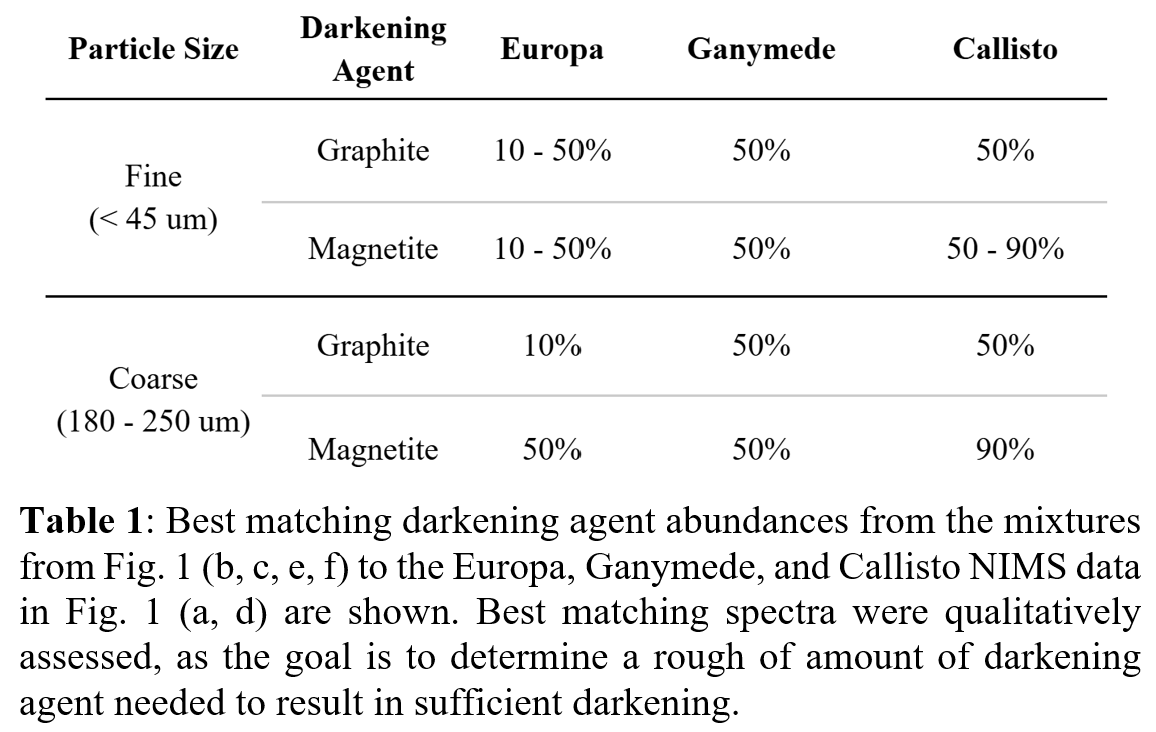

Hapke radiative transfer modeling [9] was used to produce spectra of each mixture to investigate model accuracy and limitations. Figure 2 shows a comparison of the 1 wt.% fine graphite mixture to a modeled spectrum produced by a nonlinear least square fitting algorithm to the Hapke reflectance equation. The best-fitting model spectrum used 0.3% graphite (45 μm), 49.37% water (36 μm), and 50.33% sulfuric acid octahydrate (45 μm).

Discussion:

Definitive statements about upper and lower limits of darkening agents through comparisons between NIMS data and lab mixtures (Table 1) are difficult to make. The surfaces of these bodies are undoubtedly more complex than simple three-component mixtures. However, we can still draw rough conclusions based on darkening agent abundances that give similar reflectance levels, despite not being able to match features perfectly.

Europa’s spectrum is closest to the 10 and 50 wt.% graphite and magnetite mixtures at fine and coarse particle sizes. For graphite, 10 wt.% is within previous darkening agent abundance estimates, but 50 wt.% of either graphite or magnetite is much higher than any reported darkening agent abundance. Ganymede’s spectra fall within expected ranges, suggesting that the darkening agent on Ganymede may be graphite, magnetite, both, or a similar material. At fine and coarse sizes, 50 wt.% magnetite is close to a lower limit of needed darkening agent abundance, as the Ganymede spectrum is darker by ~0.05. However, 90 wt.% graphite may serve as an upper limit, as the 90 wt.% mixture is darker than the Ganymede spectrum. An upper limit for magnetite or graphite of either particle size may be near 90 wt.% for Callisto.

Mixture results additionally highlight the overall plausibility of some darkening agents. For example, fine and coarse magnetite abundances need to be near 90 wt.% to match Callisto’s surface in some regions. Our mixtures may be spectrally similar to the Callisto spectrum; however, this is likely not representative of Callisto’s actual surface composition. The main avenue by which magnetite, or any Fe-rich material, can be delivered to Callisto’s surface is through (micro)meteorite impacts. A significant flux of Fe-rich impactors needed to have been present near Callisto to provide this amount. Graphite or C-bearing materials are more feasible. They can be delivered via (micro)meteorite bombardment, produced through radiolytic breakdown of surface C materials like CO2, or may also be sourced endogenically like on Europa, where CO2 signatures are linked to chaos terrain [10].

Laboratory mixtures were compared against Hapke modeled spectra to probe model limitations, especially in mixtures of very bright and very dark materials. More work needs to be done, but Figure 2 suggests the Hapke model struggles to reproduce visible wavelengths when the reflectance of bright materials is near unity. Figure 1 disagrees with the longstanding notion that a few wt.% dark materials can significantly darken bright materials when mixed. The agreement between Hapke-derived abundance with the actual abundances used in each mixture suggest this idea may not be true when the materials being mixed are at opposite reflectance extrema.

References:

[1] Strazzulla, G., et al., (2023). Earth Moon Planets 127, 2. [2] Carlson, R. W., et al., (1999) Science 286, 97-99. [3] Carlson, R. W., et al. (2002) Icarus 157, 456-463. [4] Dalton III, J. B., et al. (2013) Pl and Sp. Sci 77, 45-63. [5] Ligier, N., et al. (2019). Icarus 333, 496-515. [6] Tosi, F., et al. (2023) Nature Ast. 8, 82-93. [7] Ligier, N., et al. (2019). EPSC 13, 492-2. [8] Clark, C. (1982) Icarus 49, 244-257. [9] Hapke, B. (1981) JGR: Solid Earth 86, B4, 3039-3054. [10] Trumbo, S., et al., (2023) Science 381, 1308-1311.

How to cite: Hayes, T. and Li, S.: Constraining possible darkening agents on the surfaces of the icy Galilean moons, EPSC-DPS Joint Meeting 2025, Helsinki, Finland, 7–13 Sep 2025, EPSC-DPS2025-1097, https://doi.org/10.5194/epsc-dps2025-1097, 2025.

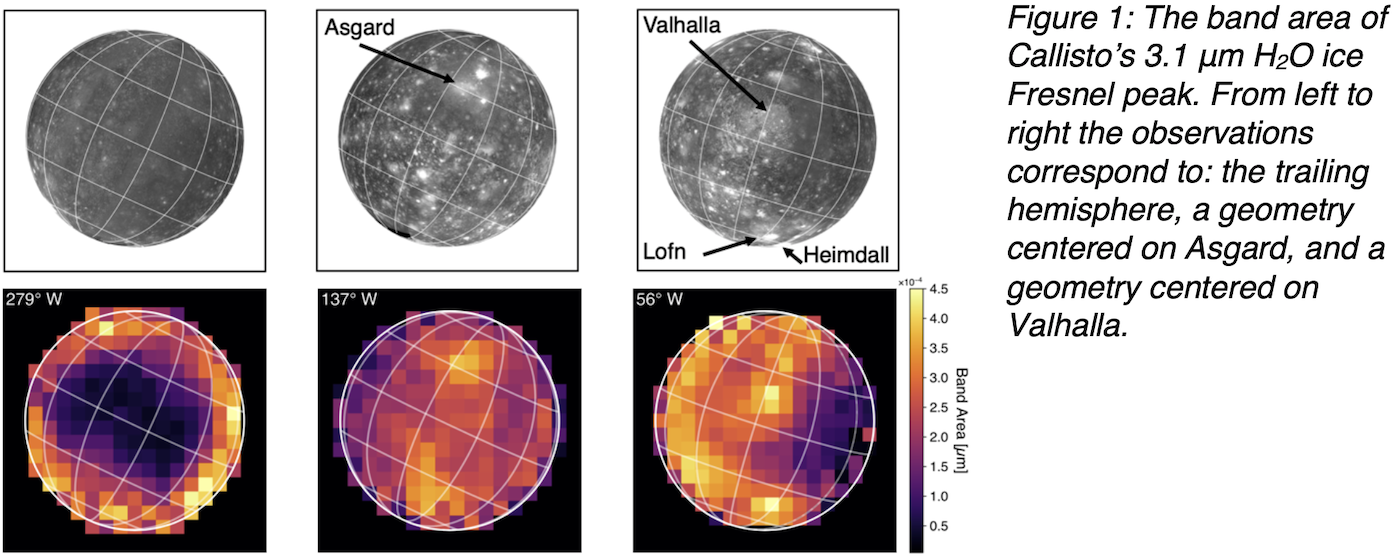

Background

Sodium chloride (NaCl), the most common salt on Earth, has been detected at several icy worlds that could be habitable in the present day, including Europa [1], Enceladus [2], Ganymede [3] and Ceres [4], providing evidence that salty liquid water from their interiors has been delivered to their surfaces. Areas that have experienced the emplacement of subsurface fluids through mechanisms such as plumes could contain a record of recently exposed ocean material and thus provide information on ocean chemistry and potential habitability. Identifying such regions will be a major priority for upcoming missions such as ESA’s JUpiter ICy moons Explorer (JUICE) and NASA’s Europa Clipper.

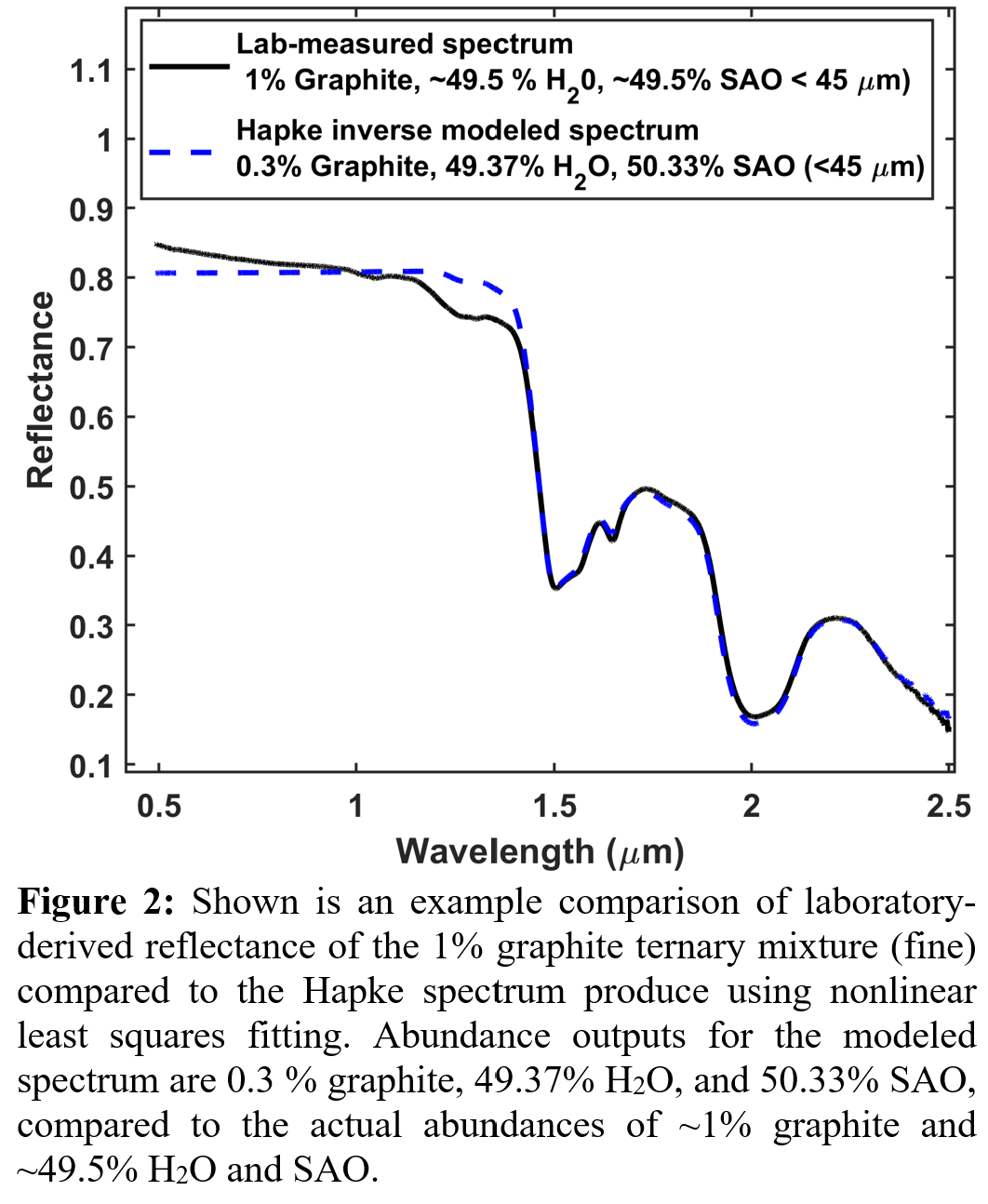

Here, we report the discovery of a metastable NaCl dihydrate formed through rapid freezing of a NaCl solution at ambient pressure (Fig. 1) [5]. This new NaCl hydrate expands on the recently identified NaCl hydrates formed in high-pressure experiments [6], and together with these reveals a rich phase behaviour in the low temperature Na-Cl-H2O system that had been overlooked for over 200 years. Using synchrotron X-ray and neutron powder diffraction, we show that the metastable form transforms irreversibly to the stable hydrate hydrohalite above 190 K, exothermically releasing 3.47 kJ mol-1 of latent heat. Additionally, we used Raman and near-infrared (NIR) reflectance spectroscopy to show experimentally that the solid phase composition of NaCl-bearing ices varies as a function of fluid cooling rate, promising a means of reconstructing the formation history of NaCl-bearing icy world surface materials from remote measurements of their composition.

Methods

NaCl solutions were frozen from room temperature to liquid nitrogen (LN2) temperature (~77 K) using multiple techniques that allowed us to probe a wide range of cooling rates spanning < 1 K min-1 to > 107 K min-1. Neutron and X-ray diffraction (XRD) were carried out at ISIS Neutron and Muon Source and Diamond Light Source, UK, respectively. We exploited the diagnostic Raman signatures of the stable and metastable hydrates [5] to identify the cooling rates required for their formation, and how these varied with NaCl concentration. NIR spectra were recorded at wavelengths between 1.0 and 2.5 micron from powdered samples at 77 K.

Figure 1. (a) Updated phase diagram of the low-temperature NaCl-H2O system incorporating phase behavior of high-pressure hydrate 2NaCl·17H2O (SC8.5 [6]) and proposed metastable dihydrate (SC2-II, this study, [5]). Dashed lines indicate observed metastable transition temperatures to hydrohalite (SC2-I) and ice Ih. (b) Neutron diffraction patterns for a flash frozen sample that has been heated. Bragg peaks for the new NaCl hydrate are marked with arrows, while Bragg peaks for hydrohalite (SC2-I) and ice Ih are marked with dashed lines (reproduced from [5]).

Results and Discussion

Our findings contribute to a new recognition of overlooked structural diversity and phase behavior complexity in the low-temperature NaCl-H2O system. We found that the newly discovered hydrate is a dihydrate structurally related to hydrohalite, with a proposed crystal structure comprising a 3 × 1 × 3 supercell of the hydrohalite unit cell. Because the metastable hydrate forms from liquid solutions at low pressures, it could feasibly form directly through cooling of ocean water at the surface or within the shallow ice shells of icy worlds and remain stable unless warmed above ~190 K. At active icy worlds such as Enceladus and Europa, rapid cooling of fluids could be achieved in various geological scenarios including plumes and chaos formation.

We found that the phase composition of NaCl-bearing ice is dependent on the cooling rate, indicating that compositional properties of NaCl-rich ices can act as a record of thermal history. At rates below ~90 K min-1, only the stable hydrohalite was produced. The metastable phase formed in distinct cooling rate regimes either in combination with hydrohalite, or as the sole NaCl phase. In addition, we used XRD to confirm that vitreous glass forms at the fastest rates, a phenomenon which has been proposed by previous studies [7,8]. Finally, we show that the new hydrate possesses near-infrared spectral features that are distinct from hydrohalite and thus could be used to identify it with existing or future remote sensing observations.

Our data show that in such regions distinguishing between different NaCl phase assemblages holds great promise in reconstructing the formational cooling rate of salty surface materials. Connecting surface composition to ice shell processes is a next major frontier in understanding the geology of icy worlds, a challenge that can be addressed by combining laboratory insights with new observations from upcoming planetary missions including NASA’s Europa Clipper and ESA’s JUICE.

References

[1] S.K. Trumbo et al. (2019). Sci. Adv., 5, eaaw7123

[2] F. Postberg et al., (2009). Nature, 459, 1098–1101

[3] F. Tosi et al., (2024). Nat. Astron., 8, 82–93

[4] M.C. De Sanctis et al., (2020) Nat. Astron. 4, 786–793

[5] R.E. Hamp et al. (2024). J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 15(50), 12301–12308

[6] Journaux et al., (2023). PNAS, 120 (9) e2217125120

[7] M.G. Fox-Powell & C.R. Cousins, (2021). J. Geophys. Res. Planets, 126, e2020JE006628

[8] F. Klenner et al. (2025) Planet. Sci. J. 6 (65)

How to cite: Hamp, R., Salzmann, C., Fawdon, P., Amato, Z., Beaumont, M., Chinnery, H., Henry, P., Headen, T., Perera, L., Thompson, S., and Fox-Powell, M.: Metastable hydrate of sodium chloride: A new mineralogical indicator of rapid freezing of brines at icy worlds, EPSC-DPS Joint Meeting 2025, Helsinki, Finland, 7–13 Sep 2025, EPSC-DPS2025-1413, https://doi.org/10.5194/epsc-dps2025-1413, 2025.

The icy moons of Jupiter and Saturn, such as Europa, Ganymede, Callisto, and Enceladus, are expected to host saltwater oceans beneath their icy crusts, raising the intriguing possibility of habitability in these water-rich environments. The distribution and compositions of salts, both dissolved in the oceans and present in solid form as hydrates, are key factors in shaping the internal structures and evolutionary pathways of these icy worlds. Constraining the compositions of salts and salt hydrates detected on icy moon surfaces provides critical insights into the geochemistry of the subsurface oceans and interior processes.1 Salt-water interactions under the high-pressure, low-temperature conditions characteristic of icy moon interiors give rise to a diverse range of hydrated salt structures that are not always accessible through temperature variations alone.2 However, relatively few experimental studies have investigated the combined effects of pressure and temperature on these systems.

Here we characterise the binary salt-water systems of NaCl,2 KCl, MgCl2, and CaCl2 under high-pressure, low-temperature conditions (0–2 GPa; 300–150 K) using in situ single-crystal synchrotron X-ray diffraction experiments to constrain the mineralogy of the chloride salts in icy moon interiors. This structural work, along with planned spectroscopic measurements, will help establish a foundation for identifying high-pressure salt hydrates that have been transported from the internal hydrosphere to the surface.

1. Dalton, J. B. et al. Chemical Composition of Icy Satellite Surfaces. Space Sci Rev 153, 113–154 (2010).

2. Journaux, B. et al. On the identification of hyperhydrated sodium chloride hydrates, stable at icy moon conditions. PNAS 120, e2217125120 (2023).

How to cite: Collings, I., Journaux, B., Pakhomova, A., Boffa Ballaran, T., and Kurnosov, A.: Salt hydrate mineralogy at the conditions of icy moon interiors and surfaces, EPSC-DPS Joint Meeting 2025, Helsinki, Finland, 7–13 Sep 2025, EPSC-DPS2025-915, https://doi.org/10.5194/epsc-dps2025-915, 2025.

Introduction: On the surface of Jupiter's icy moons Europa and Ganymede, non-water ice materials are mixed with water ice at different proportions. Hydrated minerals can mimic the 1.5 and 2.0 μm water ice absorption bands. In particular, the presence of hydrated magnesium sulfate, such as hexahydrite (MgSO4∙6H2O), was first suggested on the surface of these icy bodies based on Galileo/NIMS data, which could be a remnant of past extrusion of liquid water from an ocean below [1]. Although other compounds, particularly chloride salts, have subsequently been proposed to explain spectral signatures observed by NIMS, the key interest for future close exploration is to understand whether these non-water ice materials are distinguishable in mixtures with water ice, and whether they are of exogenic or endogenic origins. Characterizing such minerals under environmental conditions similar to those found on the icy moons' surfaces is therefore crucial, especially considering the link between the presence of hydrated salts on Solar System bodies and geological processes that occurred in the presence of liquid water, with potential implications for the establishment of a habitable environment.

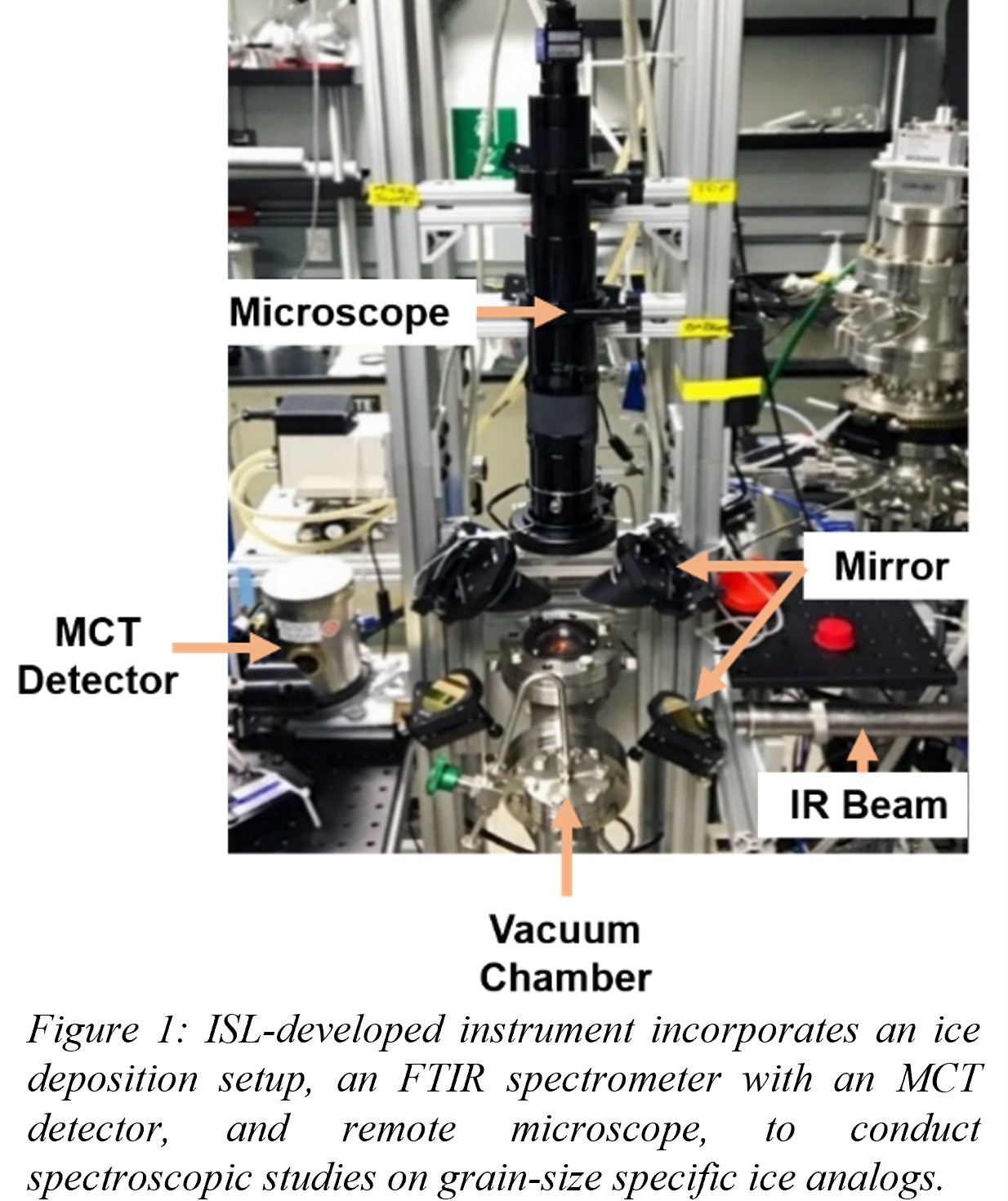

This work is also important to support the future observations of the MAJIS (Moons and Jupiter Imaging Spectrometer) instrument [2,3] onboard the ESA JUICE mission. Although similar work on hexahydrite was carried out previously [4,5,6], the MAJIS spectral sampling, which is 3.6 nm from 0.50 to 2.35 μm and 6.5 nm from 2.25 to 5.54 μm, motivates performing new laboratory measurements at higher spectral resolution.

Experimental procedure and results: For this objective, we prepared powders of hexahydrite at different grain sizes, ranging from 50 to 500 μm, to study the variation of the spectral features in the infrared and visible spectral ranges depending on the environmental conditions. The set of measures described in this abstract was performed as a deeper investigation following the measures taken with a different setup, CAPSULA [7]. We acquire both the reflectance and the visible image of the sample with a microscope coupled with an FTIR spectrometer and equipped with a cryogenic cell [Figure 1] that contains the sample in a controlled environment, which can go down to a pressure of 10-4 mbar, and a temperature of 40 K. Different grain sizes of the sample were put inside the cryogenic cell thanks to a custom sample holder which allows the acquisition of different grain sizes during one single data taking [Figure 2], and brought to a pressure of 10-4 mbar while acquiring spectra during the process. The reflectance spectra and the computed spectral parameters show that there is more than one critical pressure at which the sample starts to change part of its lattice structure. Moreover, different grain sizes respond differently to the pressure variation, as shown in Figures 3 and 4.

Figure 1: Experimental setup composed of a cryogenic cell that allows a controlled environment where we put the sample, and a microscope coupled with an FTIR spectrometer that enables both the acquisition of the spectral radiance and the visible image of the samples.

Figure 2: Custom sample holder placed inside the cryogenic cell. It contains 4 different grain sizes of hexahydrite.

Figure 3: Infrared reflectance spectra of different grain sizes of hexahydrite powder at room pressure and room temperature.

Figure 4: Close-up of the 2 microns water diagnostic absorption band in the continuum-removed reflectance spectra of a hexahydrite powder with a grain size between 50 and 75 microns at different pressures and room temperature. The sample shows a first spectral variation at around 100 mbar and a second one between 5 and 10-1 mbar.

Conclusions: The results shown here may constrain the correlation between the spectral features of this kind of material, planetary analogs for the icy satellites, and their physical properties. One of the most interesting aspects we came across is a change in the lattice structure of this sample, which seems incompatible in its crystalline and hydrated form (hexahydrite) at the extremely low pressure on the surface of the icy moons, that is, in the range 10-8 -10-12 mbar. In the laboratory, the process of amorphization and dehydration with vacuum occurs in a timescale of tens ofminutes at room temperature. Therefore, if hexahydrite was present on these bodies, it should be continuously replenishedor ephemeral, and this may sustain the subsurface liquid water as a possible source. On thesurface of Europa and Ganymede, this type of hydrated salt could eventually bepreserved thanks to some mechanism that involves the rapid emplacement in simultaneoussurface conditions of low temperatures and ultra-high vacuum. In this regard, a deeper laboratory investigation is required.

These results are extremely important to avoid any ambiguity in the determination of the surface composition of the icy moons of Jupiter once the data MAJIS will acquire is available, and could also allow some constraints on what could be present underneath the surface.

References:

[1] T.B. McCord et al., Icarus, 209, 639-650 (2010)

[2] G. Piccioni et al., IEEE 5th International Workshop on Metrology for AeroSpace, 318-323 (2019)

[3] F. Poulet et al., Space Sci Rev, 27, 220 (2024)

[4] T.B. McCord et al., JGR, 104, 11827-11851 (1999)

[5] J.B. Dalton et al., Icarus, 177, 472-490 (2005)

[6] S. DeAngelis et al., Icarus, 281, 444-458 (2017)

[7] De Angelis S. et al. (IN PRESS) Mem. S.A.It., 75, 282.

Acknowledgements: This work has been developed under the ASI-INAF agreement n. 2023-6-HH.0. This work is supported by EU and Regione Campania with FESR 2007/2013 O.O.2.1

How to cite: Furnari, F., Piccioni, G., Rubino, S., Stefani, S., De Angelis, S., Tosi, F., Carli, C., Ferrari, M., and La Francesca, E.: Spectroscopic measures of hydrated sulfate as a relevant planetary analogue for Jupiter’s icy moons, EPSC-DPS Joint Meeting 2025, Helsinki, Finland, 7–13 Sep 2025, EPSC-DPS2025-654, https://doi.org/10.5194/epsc-dps2025-654, 2025.

Introduction: There is a growing consensus that ocean-derived impurities, and particularly salts, play a key role in the geophysical evolution and habitability of planetary ice shells [1]. This is bolstered by several observations including 1) the association of endogenic material with geologically young surface features, 2) the ability of salts to depress the freezing temperature and extend the longevity of liquids within planetary ices, 3) the critical role salts play in governing the material properties, biogeochemistry, and habitability of salt-rich ice, and 4) the fundamental role small melt fractions and impurity levels play in the analogous terrestrial mantle-lithosphere system [2]. As the primary medium for the transport and expression of observable signatures from underlying oceans these impurity enriched ices provide a geological record of subsurface ocean properties and processes.

Given these geophysical and astrobiological implications, there has been a recent effort to constrain the material entrainment rates occurring at ice-ocean and ice-brine interfaces [3]. Bred from multiphase models of analogous terrestrial systems (sea ice, magma chamber dynamics, solidifying metal alloys), these investigations have produced parameterizations linking interface conditions to material entrainment rates and resultant ice properties [2-3]. Moreover, they have been validated against salinity profiles and material entrainment rates observed in natural and laboratory grown sea ice cores [3]. That said, it is likely that the ocean compositions of other ocean worlds in the solar system may differ from that of the Earth. If this is the case, it bodes the question, are all salts species entrained at an equal rate? Recent research suggests that ion fractionation, the preferential entrainment/rejection of salt species into/out of the forming ice, could be prevalent under ice-ocean world thermodynamic conditions [4]. If so, ionic speciation within planetary ices may not be directly representative of the progenitor fluid reservoir from whence they came.

While there exist extensive ionic composition measurements for ice cores derived from our own NaCl-dominated ocean, investigations of ion fractionation in natural ices have been inconclusive and even contradictory [4-5], and there currently exists a dearth of empirical data related to the ionic composition of ices formed from alternate ocean chemistries [2]. As such, there remains a large gap in our understanding of the entrainment rates of various salt species in ices formed from planetary relevant brines. Moreover, contemporary models of ice-brine systems that include the physics needed to describe ion fractionation (e.g., multispecies ion diffusion, salt precipitation) [6] are in desperate need of empirical measurements to assess their accuracy.

These are potentially critical processes operating within the ice shells of ocean worlds, controlling their geochemistry, geophysics, and habitability [4]. As such, a well constrained dataset of salt entrainment rates in compositionally diverse ices is needed to improve our understanding of the physics governing these high-priority systems and benchmark evolving predictive models of planetary ice-brine systems to guarantee their accuracy and optimize their utility for upcoming missions (e.g., Europa Clipper, Dragonfly).

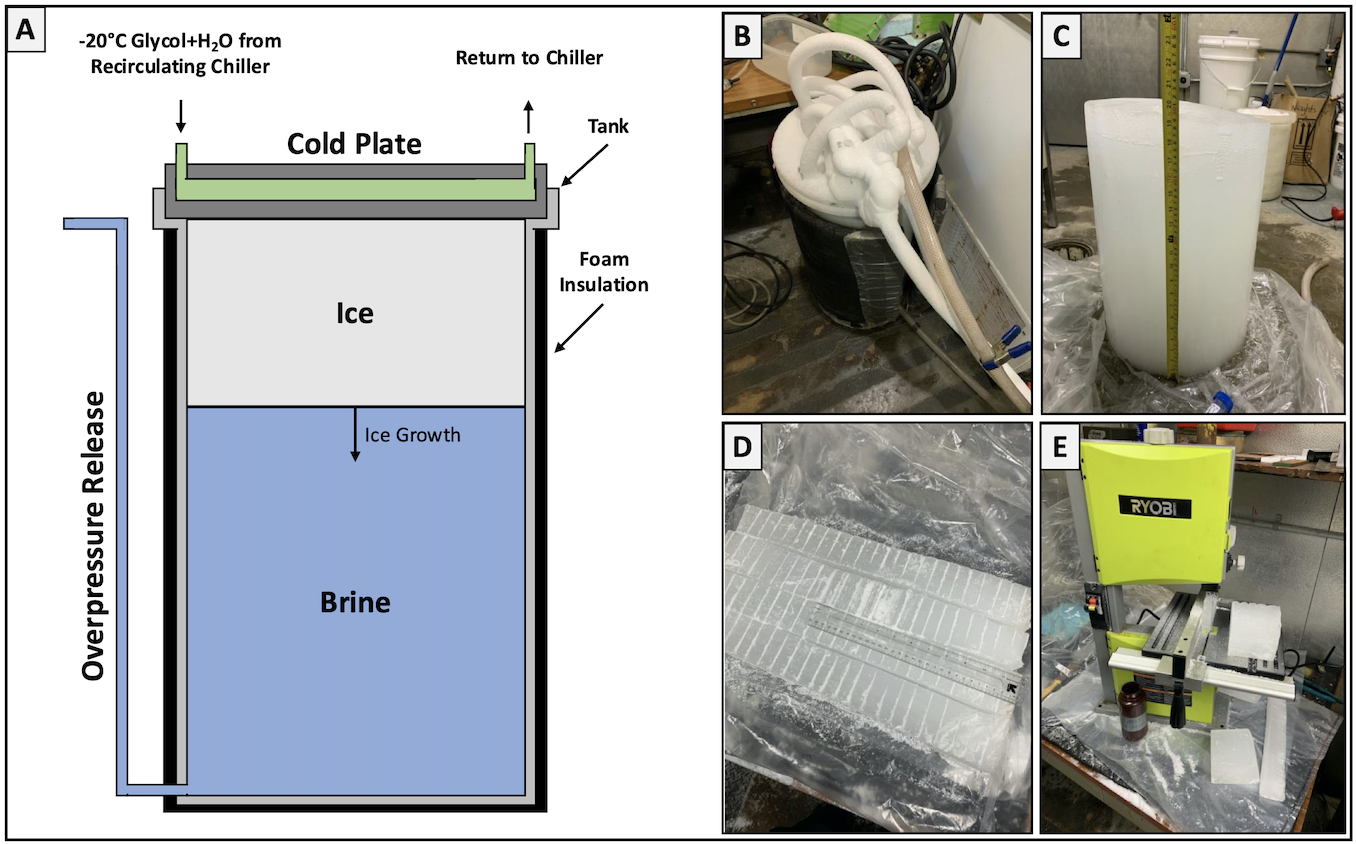

Methods: To bridge this knowledge gap, we have carried out novel top-down ice growth experiments (Figure 1) and established a database of physical, thermal, chemical, and material properties of compositionally diverse saline ices grown from putative ice-ocean world ocean compositions (NaCl, MgSO4, and Na2CO3 dominated). Leveraging the ionic composition and temperature profiles of these ices alongside the equilibrium geochemistry software PHREEQC, we additionally simulate their mineralogical assemblages and interstitial brine properties (e.g., water activity, ionic concentration) – key characteristics when assessing aqueous environment habitability [7].

Figure 1 – Ice growth apparatus and vertical sectioning for ionic composition/fractionation analysis.

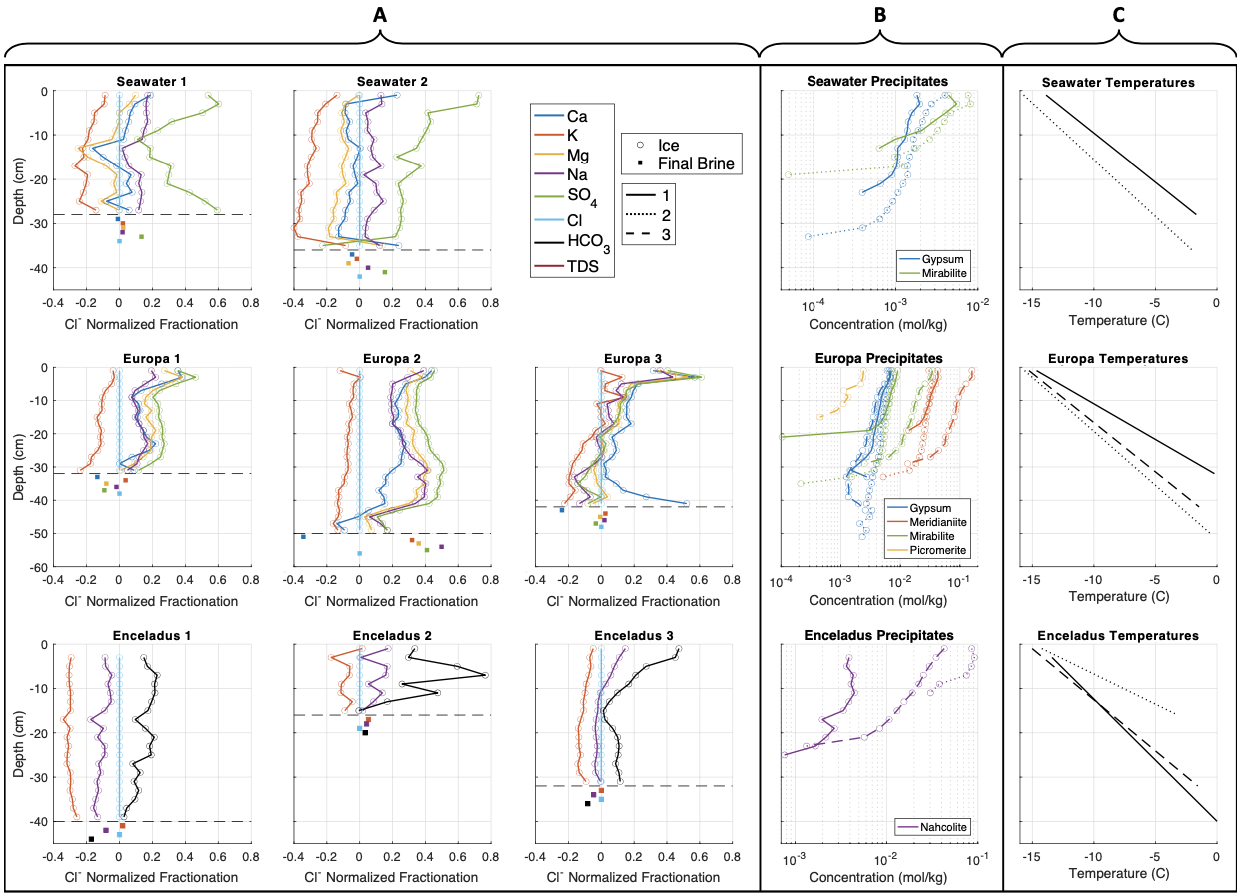

Results: Here we present ionic composition and fractionation profiles of these ices, as well as their associated hydrate minerology and liquid phase properties (e.g., Figure 2). We describe the novel physics that govern the diverse evolution of these complex multiphase systems, such as multispecies ion diffusion and thermochemically dependent precipitation pathways. We show that:

- Ion fractionation signals are present in all of our analog ice samples.

- Depletions and amplifications in relative ion abundance, compared to the source fluid, range from -40% to +77%.

- The level of fractionation is dependent on both the thermal and chemical conditions under which the ice forms.

- The simulated precipitate mineralogical assemblages throughout the ice columns are consistent with the fractionation signals.

- The observed amplifications and depletions of relative ion concentrations (compared to the parent underlying fluid) are consistent with the processes of hydrate precipitation and multispecies diffusion, respectively.

- The ionic composition of saline ices are not necessarily a reflection of the relative ion abundances of the fluid from whence they formed – i.e., all salts are not entrained at an equal rate.

We discuss the important implications these results have for our understanding of ice-ocean world geophysics, habitability, and mission science interpretation.

Figure 2 – Ion fractionation profiles in analog ice cores (A). Amplifications relative to Cl- correlate with precipitated minerals, while depletions are associated with amplified diffusion rates. Simulated mineralogical assemblages (B) using in situ temperatures (C) agree with observed fractionation signals.

Conclusions: Through novel laboratory measurements we demonstrate that ion fractionation in planetary ices is likely a prevalent process, capable of generating heterogeneous and compositionally diverse ices – even from the same parent fluid. The resultant geochemical complexity of these ices directly correlates to associated variations in ice material properties (e.g., melting points, strengths, viscosity, porosity, etc.) that will significantly impact the geophysical processes and habitability of planetary ice shells. As high-priority planetary science and astrobiology targets for current and upcoming missions constraining the chemical and thermophysical properties of planetary ices and their relationships to the characteristics of their underlying oceans will be imperative for constraining predictive models of these environments and maximizing the science return from observational datasets.

References: [1] Vance S. D. (2021) JGR: Planets, 126.1. [2] Buffo J. J. et al. (2023) JGR: Planets, 128.3. [3] Buffo J. J. et al. (2020) JGR: Planets, 125.10. [4] Wolfenbarger N. S. et al. (2022) Astrobiology, 22.8, 937-961. [5] Maus S. et la., (2011) AoG, 52.57. [6] Meyer et al., (2024), AbSciCon, 412.03. [7] Wolfenbarger N. S. et al., (2022) GRL, 49.22.

How to cite: Buffo, J., Fox-Powell, M., Murdza, A., Tomlinson, T., Schultz, A., Barton, T., Gurd, C., McEwen, A., Wolfenbarger, N., Chivers, C., Schmidt, B., and Meyer, C.: As Above, Not So Below: Ion Fractionation in Planetary Analog Ices, EPSC-DPS Joint Meeting 2025, Helsinki, Finland, 7–13 Sep 2025, EPSC-DPS2025-823, https://doi.org/10.5194/epsc-dps2025-823, 2025.

Background

Europa's icy surface is exposed to low pressures and subject to intense radiation, resulting in complex processes such as sublimation and radiolytic modification that influence its spectral properties. Interpreting reflectance spectra from future missions like Europa Clipper and JUICE requires understanding how salts in Europa’s surface ice evolve under such conditions. Specifically, the formation and stability of hydrated salts such as hydrohalite (NaCl·2H₂O) are of great interest.

Methods

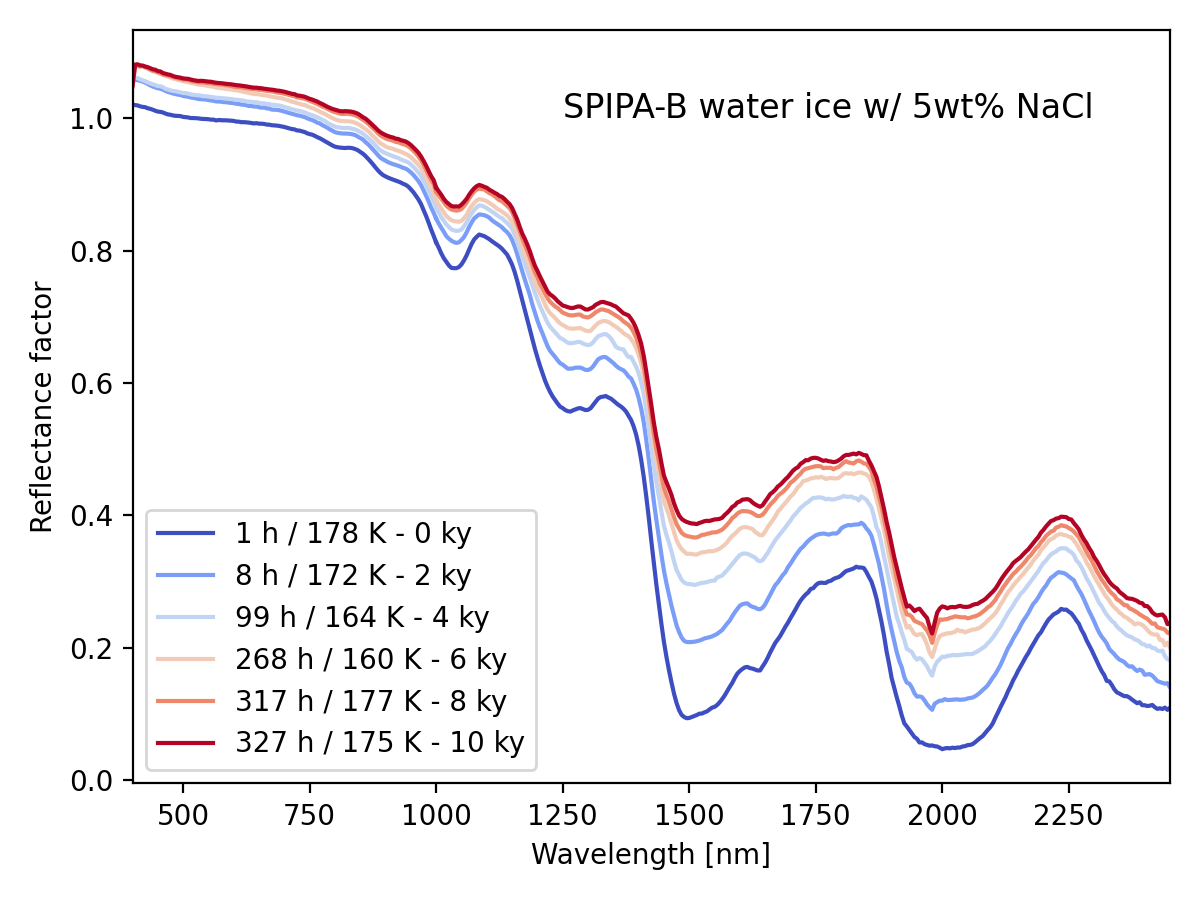

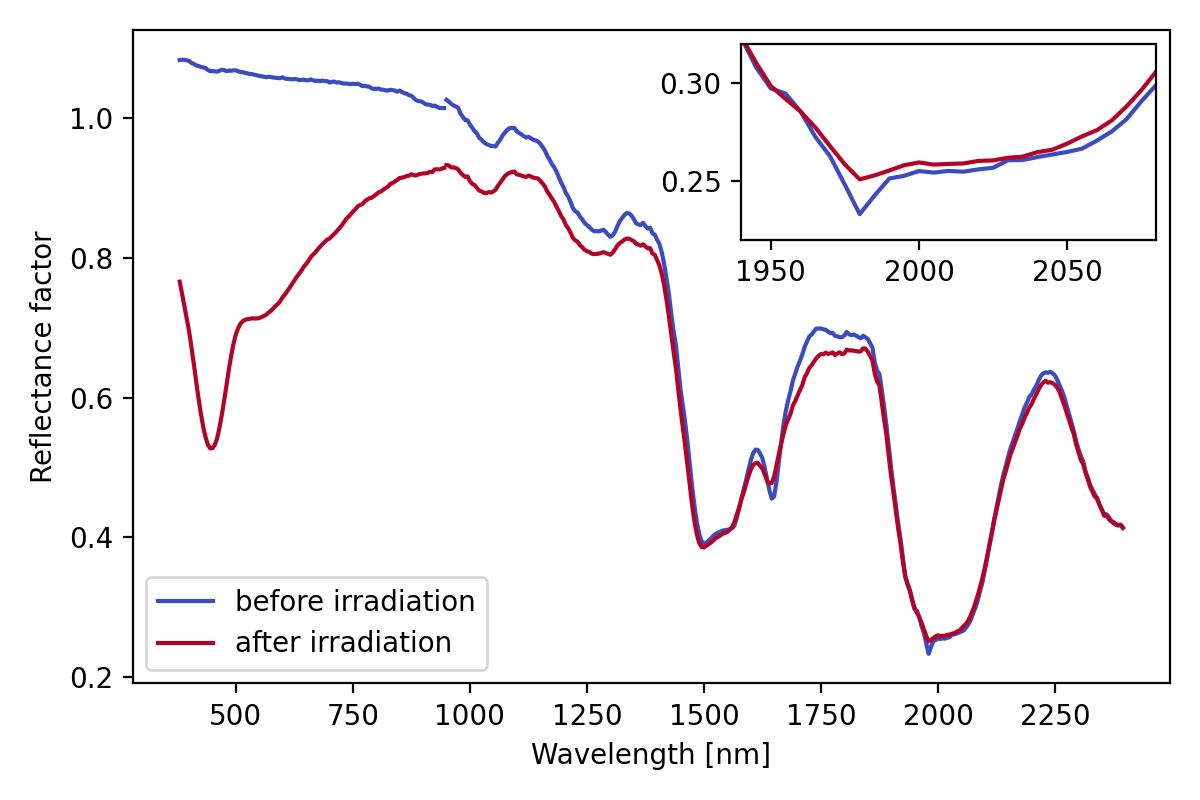

Granular icy analogs containing NaCl, MgSO₄, and MgCl₂ were produced by flash-freezing brine droplets with 5 wt% salt content. These samples were put in a vacuum chamber, simulating the surface evolution at low pressures and temperatures over hundreds of hours. A novel application of a thermopile sensor, with a custom sensor mount and calibration algorithm, allowed direct surface temperature measurement (160–185 K), enabling us to scale laboratory sublimation timescales to equivalent durations under Europa conditions. Reflectance spectra were acquired in the 400–2500 nm range using a hyperspectral imaging system. In a separate set of experiments, NaCl analogs were irradiated with 2 keV electrons to simulate Europa’s radiation environment and study the stability of observed spectral features.

Results

Sublimation caused notable changes in the reflectance spectra of all analog samples over hundreds of hours, which can be scaled to Europa-equivalent timescales of less than 10’000 years. The broad water absorption bands around 1.5 µm and 2.0 µm became shallower over time, and the overall reflectance increased, indicating the formation of optically dominant salt crusts on the surface due to water loss. The equivalent geometric albedo of all samples increased by more than 10% during sublimation, implying a substantial change in the surface's thermal properties.

In the NaCl-containing samples, a distinct narrow absorption band emerged at 1.98 µm, consistent with the formation of hydrohalite (NaCl·2H₂O) during sublimation, as can be seen in Figure 1. In contrast, samples containing MgSO₄ and MgCl₂ did not show narrow hydration bands during sublimation. However, changes in the shape of the 2 µm band were observed, with a slight skew in the MgSO₄ sample and a strong asymmetry in the MgCl₂ sample, both toward shorter wavelengths.

To investigate the stability of the hydrohalite feature, the NaCl samples were exposed to 2 keV electron irradiation at a total dose of 3.4 × 10¹⁶ electrons / cm². The 1.98 µm feature was significantly diminished after irradiation, corresponding to just a few years of surface exposure on Europa (see Figure 2). This shows a rapid dehydration of hydrohalite under electron bombardment.

These spectral and physical changes highlight the importance of accounting for sublimation and radiation effects when interpreting Europa’s surface composition from remote sensing data.

The presented data is publicly available under the DOI’s 10.26302/SSHADE/EXPERIMENT_RO_20240312_001 and 10.26302/SSHADE/EXPERIMENT_RO_20240701_000.

Conclusions

Our results demonstrate that sublimation alters the reflectance spectra of salty ice on Europa over short geological timescales. Sublimation processes must be accounted for in spectral interpretations to avoid overestimating bulk salt abundances. The formation of hydrohalite during sublimation and its rapid destruction under irradiation implies it is unlikely to be stable under typical conditions on Europa’s surface. If hydrohalite is present on the surface, it is either freshly exposed material (<10 years) or sustained by thermal anomalies (>145 K). Thus, any detection of hydrohalite in future observations would strongly indicate recent surface activity.

Figure 1: Sublimation of a grainy ice analog containing 5 wt% NaCl. The relative laboratory time and the measured surface temperature for all spectra are shown in the legend. The estimated timescales in the unit of 1000 years (ky), when the sublimation kinetics are scaled to Europa’s equatorial conditions, are given after the dash.

Figure 2: The reflectance spectra of a grainy ice analog with 5 wt% NaCl. The two lines show the reflectance before and after irradiation with 2 keV for 10 min with a current of 10 µA. The irradiation leads to the formation of color centers in the Vis and reduces the depth of the absorption band at 1.98 µm.

How to cite: Ottersberg, R., Pommerol, A., Stöckli, L. L., Obersnel, L., Galli, A., Murk, A., Wurz, P., and Thomas, N.: Evolution of Granular Salty Ice Analogs for Europa: Sublimation and Irradiation, EPSC-DPS Joint Meeting 2025, Helsinki, Finland, 7–13 Sep 2025, EPSC-DPS2025-529, https://doi.org/10.5194/epsc-dps2025-529, 2025.

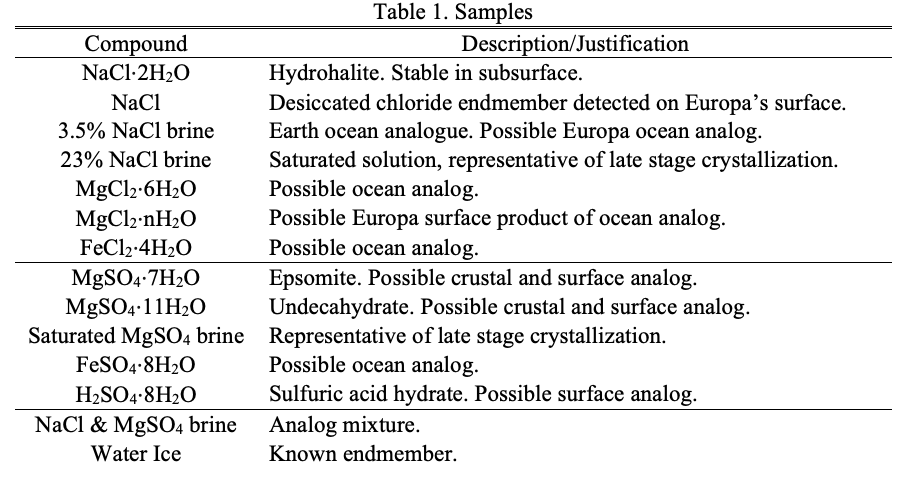

Introduction: The non-ice materials on the surface of Europa provide insight into its geologic history, the exogenous processes that affect its surface, and by extension the composition of its subcrustal ocean. Europa has been known to be covered by water ice and other (non-ice) materials, both trace and in abundance. Here we report on the use of spectroscopy at visible wavelengths to help constrain the composition of the non-ice material(s) on Europa’s surface. The visible to near infrared brightness and color of salts are affected by energetic particle radiation [e.g. 1,2].

Methods: Fourteen different materials investigated potentially representative of Europa’s surface, frozen subsurface and ocean compositions were investigated. They include halides and sulfates of Na, Mg, and Fe as well sulfuric acid octahydrate and water ice (Table 1). Visible and infrared reflectance spectra from ~ 400 to ~ 2500 nm or 8000nm were obtained of the materials in pellet form before and after irradiation using the LabSPEC facility at the John Hopkins Applied Physics Laboratory. All samples were in the form of pellets, pressed from powdered samples. Cryogenic temperature (~ 100K) was maintained for any material not thermally stable at room temperature. However, grain size was unconstrained.

Results and Conclusions: We have found that the visible spectrum of each material was altered by electron irradiation while the infrared was largely not affected. The materials investigated included cryogenic brines, salts, and hydrates. For NaCl brines, the discoloration in visible and near infrared is sensitive to even small amounts of NaCl being present. We confirm the 460-nm absorption band observed on the leading hemisphere of Europa is indicative of desiccated NaCl, and is not representative of either hydrohalite nor its frozen cryogenic brine. The color of Europa’s leading hemisphere is more consistent with either or both hydrated sulfuric acid or magnesium sulfates (Figure 1a,b) . Other chlorides, such as variants of MgCl2 are not present in abundance. A small amount of brine may also be present to account for the ~ 15% of NaCl being necessary to produce the observed depth of the color center. The color of the trailing hemisphere is also consistent with magnesium sulfates but the extensive irradiation and effects on the spectra of these and other potential surface materials has not been adequately simulated in the laboratory at relevant fluxes to confirm this (Figure 1c,d). MgSO4 is likely a precipitate from the ocean and not a radiolytic product and it is possible that radiolytic hydrated sulfuric acid could have formed from the degradation of the sulfate. Thus, the interior ocean appears to contain sulfates as well as chlorides, with the magnesium sulfates potentially preferentially concentrating in the crust.

Results and Conclusions: We have found that the visible spectrum of each material was altered by electron irradiation while the infrared was largely not affected. The materials investigated included cryogenic brines, salts, and hydrates. For NaCl brines, the discoloration in visible and near infrared is sensitive to even small amounts of NaCl being present. We confirm the 460-nm absorption band observed on the leading hemisphere of Europa is indicative of desiccated NaCl, and is not representative of either hydrohalite nor its frozen cryogenic brine. The color of Europa’s leading hemisphere is more consistent with either or both hydrated sulfuric acid or magnesium sulfates (Figure 1a,b) . Other chlorides, such as variants of MgCl2 are not present in abundance. A small amount of brine may also be present to account for the ~ 15% of NaCl being necessary to produce the observed depth of the color center. The color of the trailing hemisphere is also consistent with magnesium sulfates but the extensive irradiation and effects on the spectra of these and other potential surface materials has not been adequately simulated in the laboratory at relevant fluxes to confirm this (Figure 1c,d). MgSO4 is likely a precipitate from the ocean and not a radiolytic product and it is possible that radiolytic hydrated sulfuric acid could have formed from the degradation of the sulfate. Thus, the interior ocean appears to contain sulfates as well as chlorides, with the magnesium sulfates potentially preferentially concentrating in the crust.

Additional laboratory work, as well as higher spatial resolution spectral mapping of Europa’s surface are needed to better constrain Europa’s surface composition. Further irradiation of cryogenic samples, especially with ions for altering the physical structure, will be necessary for refining a spectral match to Europa’s surface, especially in the infrared. We emphasize that the spectral identification of a component responsible for coloring the surface of Europa must also not be inconsistent with spectral features in the infrared and also that infrared spectra of relevant materials need to account for the spectral effects of damaging ion irradiation. For instance, subtle features, such as near 1350 nm may or may not persist under ion irradiation. Also, other types of materials need to be considered that also darken and redden in the visible, such as nano-phase metallic iron [e.g. 3], which may be a component of meteoritic contamination.

Figure 1. The VNIR spectrum of Europa’s leading hemisphere (a & b) are best matched by magnesium sulfate epsomite, magnesium undecahydrate, and hydrated sulfuric acid. The infrared is best matched by the NaCl brines, because that portion of the spectrum of the disk-integrated leading hemisphere is dominated by water-ice. It is also likely the match of sulfuric acid hydrate would improve with different sample preparations and smaller grain sizes. The trailing hemisphere (c & d) is best matched by hydrated magnesium sulfate but also a mixture of NaCl and partially hydrated MgCl2. However, MgCl2•nH2O significantly mismatches in the shortwave. An additional material absorbing at 0.6 mm continues to be needed.

Acknowledgements: This work was supported primarily by the Solar Systems Working Grant # 80NSSC20K1044 with some support also provided through the Europa Clipper MISE Contract to APL.

References: [1] Hand, K. P., & Carlson, R. W. 2015, GRL, 42; [2] Hibbitts, C. A., Stockstill-Cahill, K., Wing, B., & Paranicas, C. 2019, Icar, 326; [3] Clark, R. N., Cruikshank, D. P., Jaumann, R., et al. 2012, Icar, 218, 2.

How to cite: Hibbitts, C., Stockstill-Cahill, K., Lloyd, E., Gloesener, E., Choukroun, M., Paranicas, C., and Clark, R.: Inferring Europa Surface Composition through Visible – Infrared Spectra of keV Electron-Irradiated Cryogenic Salts and Hydrates, EPSC-DPS Joint Meeting 2025, Helsinki, Finland, 7–13 Sep 2025, EPSC-DPS2025-962, https://doi.org/10.5194/epsc-dps2025-962, 2025.

- Context. The constant flux of energetic particles reaching the surface of the Jovian Moons, in particular Europa[1], can process and destroy the potential organic species that could be found on their surface. Endogenic organics could be a window into the composition of the subsurface ocean, therefore it is critical to understand the result of their alteration to interpret the future measurements of the Europa Clipper [2] and JUICE [3] missions.

- Goals. This study was performed to determine the diversity of volatile organic products that can be obtained by irradiating methanol in conditions relevant to Europa’s surface Methanol is the simplest of alcohols, widely present in early solar system materials, and tentatively detected in another ocean world, Enceladus [4]. Its radiation chemistry is well studied but primarily in colder conditions, more relevant to small bodies of the early solar system (e.g., [5]).

- Experimental methods.

We grew pure CH3OH ices, ~5 µm thick on a copper sample holder connected to a closed cycle Helium cryostat inside a vacuum chamber. Their growth and evolution was monitored using a FTIR (Fourier-Transform Infrared) Spectrometer in the Mid-Infrared range. We then irradiated them with 10 keV electrons.

The experiments were performed at three different temperatures relevant to Europa’s surface (50 K, 80 K and 130 K), and at three different fluences: 2.12·1015 e−/cm2, 6.36·1015 e−/cm2 and 1.27·1016 e−/cm2. This last value corresponds to an exposition lasting from ~100 days to ~400 years on Europa, depending on the area of the surface [6]. After the irradiation was completed, the sample was brought back to room temperature and the resulting volatiles were transferred into a GCMS (Gas Chromatographer−Mass Spectrometer)[7], allowing for separation and unambiguous identification of volatile organic compounds that could otherwise not be detected with FTIR spectroscopy.

- Results. Post-irradiation FTIR spectra allows the identification of several common products of methanol radiation chemistry: CO2, CO, CH4, ethylene glycol and formaldehyde [7]. GCMS analysis of the volatile products shows great chemical diversity (22 species identified). These compounds include aldehydes, ketones, ethers, esters, alcohols, alkenes and some heterocycles, in different abundances depending on dose and temperature. The quantity and diversity of products differ from previous results obtained with UV irradiation[5], suggesting different branching ratios of radicals resulting from electron irradiation such as the predominance of •OCH3. The products of this experiments show that radiation processing of even simple organics could complicate the assessment of the interior conditions of Europa. As an example, the propylene/propanol ratio we obtain could, in a proposed framework based on geochemical modelling of hydrothermal fluids [8], wrongly be interpreted as evidence for high temperature hydrothermalism.

- Acknowledgements. This work was supported by CNES, focused on the JUICE mission. This work was also supported by the Programme National de Planétologie (PNP) of CNRS-INSU cofunded by CNES. We acknowledge support from CNRS Ingéniérie as part of the DERCI Programme (European Research and International Cooperation Directorate). We acknowledge support from the French government under the France 2030 investment plan, as part of the Initiative d'Excellence d'Aix-Marseille Université—A*MIDEX AMX-21-PEP-032. This research is part of the project ROC-ICE and has benefited from funding provided by l'Agence Nationale de la Recherche (ANR) under the Generic Call for Proposals 2024

[1] C. Paranicas, J. Cooper, H. Garrett, R. Johnson, and S. Sturner, “Europa’s Radiation Environment and Its Effects on the Surface,” Europa, Jan. 2009.

[2] S. M. Howell and R. T. Pappalardo, “NASA’s Europa Clipper—a mission to a potentially habitable ocean world,” Nat Commun, vol. 11, no. 1, Art. no. 1, Mar. 2020, doi: 10.1038/s41467-020-15160-9.

[3] O. Grasset et al., “JUpiter ICy moons Explorer (JUICE): An ESA mission to orbit Ganymede and to characterise the Jupiter system,” Planetary and Space Science, vol. 78, pp. 1–21, Apr. 2013, doi: 10.1016/j.pss.2012.12.002.

[4] R. Hodyss et al., “Methanol on Enceladus,” Geophysical Research Letters, vol. 36, no. 17, 2009, doi: 10.1029/2009GL039336.

[5] L. I. Tenelanda-Osorio, A. Bouquet, T. Javelle, O. Mousis, F. Duvernay, and G. Danger, “Effect of the UV dose on the formation of complex organic molecules in astrophysical ices: irradiation of methanol ices at 20 K and 80 K,” Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society, vol. 515, no. 4, pp. 5009–5017, Oct. 2022, doi: 10.1093/mnras/stac1932.

[6] P. Addison, L. Liuzzo, and S. Simon, “Surface-Plasma Interactions at Europa in Draped Magnetospheric Fields: The Contribution of Energetic Electrons to Energy Deposition and Sputtering,” Journal of Geophysical Research: Space Physics, vol. 128, no. 8, p. e2023JA031734, 2023, doi: 10.1029/2023JA031734.

[7] C. J. Bennett, S.-H. Chen, B.-J. Sun, A. H. H. Chang, and R. I. Kaiser, “Mechanistical Studies on the Irradiation of Methanol in Extraterrestrial Ices,” ApJ, vol. 660, no. 2, p. 1588, May 2007, doi: 10.1086/511296.

[8] K. J. Robinson, H. E. Hartnett, I. R. Gould, and E. L. Shock, “Ethene-ethanol ratios as potential indicators of hydrothermal activity at Enceladus, Europa, and other icy ocean worlds,” Icarus, vol. 406, p. 115765, Dec. 2023, doi: 10.1016/j.icarus.2023.115765.

How to cite: Bouquet, A., Carrasco-Herrera, R., Noble, J., Duvernay, F., and Danger, G.: Volatile organic products resulting from the electron irradiation of methanol ice: Implications for Europa’s surface organics, EPSC-DPS Joint Meeting 2025, Helsinki, Finland, 7–13 Sep 2025, EPSC-DPS2025-1315, https://doi.org/10.5194/epsc-dps2025-1315, 2025.

NIRSpec observations of Europa’s leading hemisphere have revealed that CO2 appears as a spectral doublet centered at 4.25 and 4.27 µm. Given that crystalline CO2 sublimes at 80 K in UHV and Europa’s surface reaches temperatures up to 120 K, the presence of CO2 implies an active source and a stable trapping material—both of which remain unidentified. Characterizing these processes is essential for constraining Europa’s surface chemistry and its interaction with Jupiter’s magnetosphere. Laboratory investigations so far have focused on electron irradiation of carbonic acid, C-bearing minerals, and mixtures of ice and organics, and uncovered multiple CO2 trapping mechanisms, including clathrate formation, physisorption onto minerals such as Ca-montmorillonite, and entrapment within non-ice materials. The idea that carbonate salts could be a plausible source and host material for CO2 has also been discussed, and a tentative 3.9 µm absorption feature characteristic of carbonates has been reported. However, no experimental work has directly examined irradiated carbonates as a CO2 source under conditions relevant to Europa. To address this gap, we irradiated calcite with 10 keV electrons at 50 K, 100 K, and 120 K in a vacuum chamber and monitored spectral changes and gaseous release using FTIR and mass spectroscopy. We found that CO2 is produced during irradiation; it exhibits absorption features consistent with those observed on the Galilean satellites and remains stable at temperatures beyond 100 K. Our work provides the first experimental evidence that carbonates may be a plausible source of CO2 on the Galilean moons.

How to cite: Pandya, A., Chandra, S., and Brown, M. E.: CO2 Production from Cryogenic Irradiation of Calcite, EPSC-DPS Joint Meeting 2025, Helsinki, Finland, 7–13 Sep 2025, EPSC-DPS2025-145, https://doi.org/10.5194/epsc-dps2025-145, 2025.

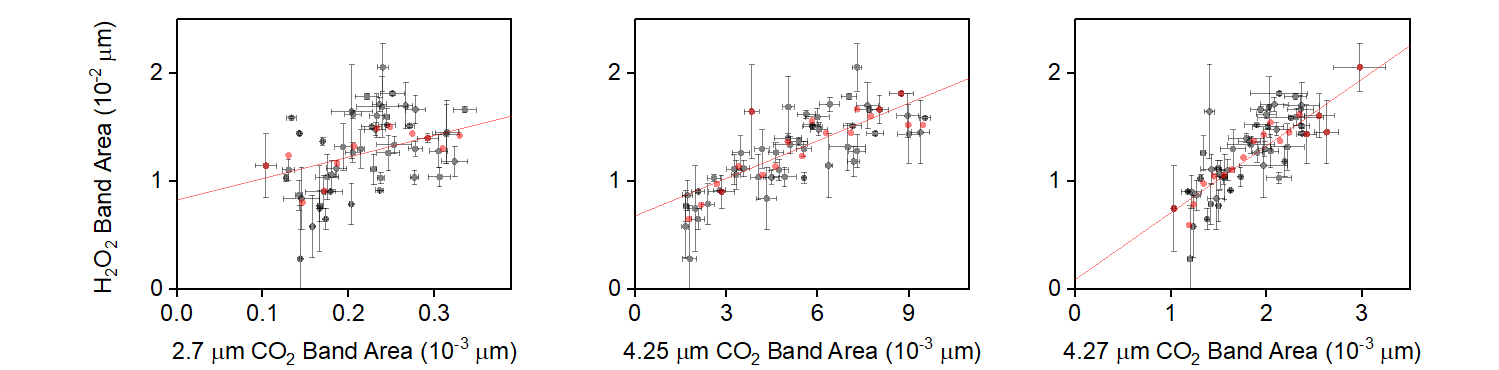

Observations of the leading side of Europa by NIRSpec aboard the JWST reveal a doublet profile of the absorption attributed to solid CO2, centered at 4.249 and 4.269 µm (Trumbo & Brown 2023; Villanueva et al. 2023). A second absorption at ~2.695 µm is also observed, which is close to the absorption at 2.71 µm of crystalline CO2. At the ultra-high vacuum conditions prevailing over the surface of Europa, the stability of solid CO2 at temperatures exceeding 70 K is intriguing (Bryson et al. (1974)). Therefore, the operation of a trapping mechanism for CO2 is considered despite the similarity of absorptions at 4.269 and 2.695 µm to that of crystalline CO2. Mapping the integrated area of the doublet across the surface conveyed increased abundance of solid CO2 at lower latitudes closer to the equator than at the poles, despite the former being warmer (Trumbo & Brown 2023; Trumbo et al. 2018). Furthermore, increased concentrations are seen at chaos terrains, with Tara Regio having the maximum concentration. All proposed mechanisms for the formation of geologically young chaos terrains involve exchange of material between ice shell and the subsurface ocean (Anderson et al. 1998; Kivelson et al. 2000; Schilling et al. 2007). This forms the basis of CO2 being endogenous, from the ocean.

Substances with carbon in their chemical composition, sourced from the ocean, could be processed by radiolysis and/or chemical reactions at the surface to generate CO2. Alternatively, CO2 could be sourced from the ocean in its native form during the migration of water ice between the ocean and surface. Distinguishing CO2 formed via these pathways given their plausible co-existence, forms another query.

We performed experiments attempting a qualitative replication of the pressure-temperature conditions surrounding CO2 retained in water ice, as the latter migrates from the ocean to the surface. Water ice and frozen NaCl brine containing CO2 were produced which were then ground at liquid N2 temperature. The diffused infrared reflectance spectra of these samples were recorded at 100 K and evacuated conditions. We observe the appearance of a doublet absorption at 4.258 and 4.278 µm and a weak absorption at 2.706 µm, characteristic of clathrate hydrates of CO2 (Oancea et al. 2012). However, these absorptions do not coincide with those observed on Europa. A separate batch of ices produced by flash freezing at temperatures below 90 K also retained CO2. The corresponding absorption also forms a doublet with blue-shifted band centers at 4.251 and 4.272 µm, while the 2.706 µm feature is absent. The doublet absorptions in both batches of ice remain stable up to 150 K for prolonged durations.

Therefore, given the mismatch of the band centers with those observed on Europa and their stability at the pressure – temperature conditions expected on Europa, we conclude that the endogenous CO2 observed at the chaos terrains is not sourced directly from the ocean. It must be the result of transformation of carbon-based materials, sourced from the ocean, driven by radiolysis and/or chemical reactions at the surface.

References

Anderson, J. D., Schubert, G., Jacobson, R. A., et al. 1998, Science, 281, 2019,

doi: 10.1126/science.281.5385.2019

Bryson, C. E. I., Cazcarra, V., & Levenson, L. L. 1974, Journal of Chemical & Engineering Data, 19, 107,

doi: 10.1021/je60061a021

Kivelson, M. G., Khurana, K. K., Russell, C. T., et al. 2000, Science, 289, 1340,

doi: 10.1126/science.289.5483.1340

Oancea, A., Grasset, O., Le Menn, E., et al. 2012, Icarus, 221, 900,

doi: 10.1016/j.icarus.2012.09.020

Schilling, N., Neubauer, F. M., & Saur, J. 2007, Icarus, 192, 41,

doi: 10.1016/j.icarus.2007.06.024

Trumbo, S. K., & Brown, M. E. 2023, Science, 381, 1308,

doi: 10.1126/science.adg4155279

Trumbo, S. K., Brown, M. E., & Butler, B. J. 2018, The Astronomical Journal, 156, 161,

doi: 10.3847/1538-3881/aada87

Villanueva, G. L., Hammel, H. B., Milam, S. N., et al. 2023, Science, 381, 1305

doi: 10.1126/science.adg4270

How to cite: Chandra, S., Denman, W. T. P., and Brown, M. E.: Arrival of CO2 from the ocean to the surface of Europa: A laboratory study, EPSC-DPS Joint Meeting 2025, Helsinki, Finland, 7–13 Sep 2025, EPSC-DPS2025-138, https://doi.org/10.5194/epsc-dps2025-138, 2025.

Please decide on your access

Please use the buttons below to download the supplementary material or to visit the external website where the presentation is linked. Regarding the external link, please note that Copernicus Meetings cannot accept any liability for the content and the website you will visit.

Forward to presentation link

You are going to open an external link to the presentation as indicated by the authors. Copernicus Meetings cannot accept any liability for the content and the website you will visit.

We are sorry, but presentations are only available for users who registered for the conference. Thank you.