- University of Hawai'i at Manoa, Hawai'i Institute of Geophysics and Planetology, School of Ocean, Earth Science and Technology, United States of America (twhayes@hawaii.edu)

Introduction:

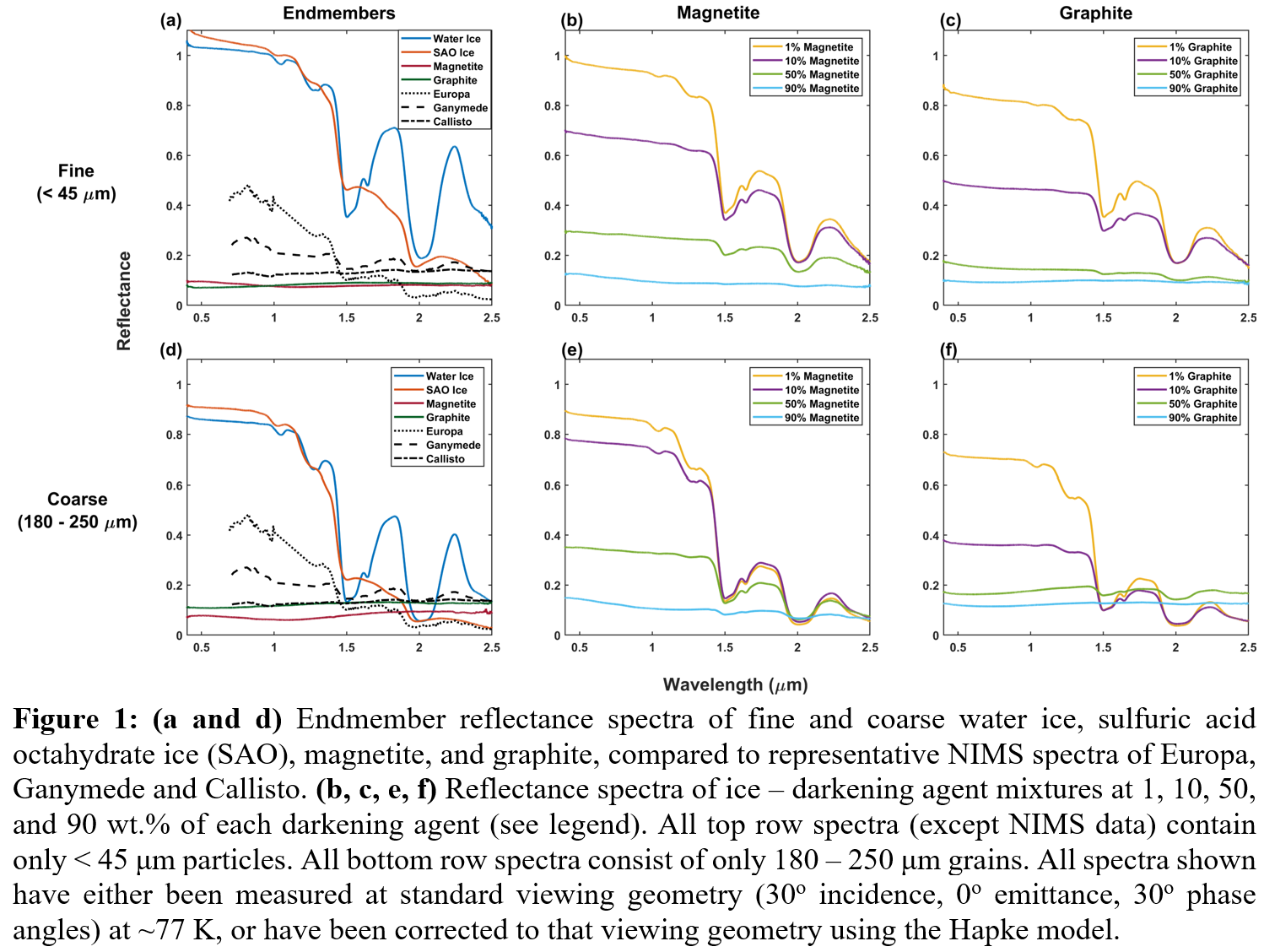

The icy Galilean moons, Europa, Ganymede, and Callisto, have surfaces with visible to near-infrared (VNIR) reflectances that are darker than expected for ices composed of water, acids, and salts. (see Figure 1a, 1d). Past investigations of these moons suggest neutral darkening agents (low reflectance and spectrally featureless materials) may be present. Common darkening agents include Fe- or C-bearing minerals, such as magnetite and graphite, which can be delivered through micrometeorite bombardment, radiolysis of surface species, or endogenic activity [1-3]

Darkening agent abundances are reportedly <20%, ~50%, and ~90% for Europa [4], Ganymede [5,6] and Callisto [7], respectively; however, large uncertainties are present in these estimates. These moons’ surfaces are likely intimately mixed due to space weathering and potential endogenic activity. A few wt.% darkening agent when intimately mixed with bright materials can drastically reduce the overall mixture’s reflectance [8]. Previous darkening agent abundances [4-7] are influenced by more than physically present species. They are sensitive to particle size effects and act as free variables for unknown surface materials. Due to this, our understanding of these moons’ surfaces and therefore the processes happening on and within them may be inaccurate.

This study seeks to provide constraints for magnetite and graphite as darkening agents in mixtures of water and hydrated sulfuric acid ices. The VNIR reflectance spectra of these mixtures are compared to those collected by the Galileo’s Near Infrared Mapping Spectrometer (NIMS) to determine rough abundances needed to achieve sufficient darkening. We additionally compare laboratory measurements with modeled spectra computed via radiative transfer theory [9] to further investigate model limitations.

Results:

VNIR reflectance spectra for mixtures of sulfuric acid octahydrate ("SAO") ice, water ice, and graphite or magnetite are shown in Figure 1 (b, c, e, f). For each darkening agent, two particle size groups are investigated, fine (<45 μm) and coarse (180 – 250 μm), to probe effects due to particle size variations. Each mixture set investigates darkening agents at 1, 10, 50, and 90 wt.%. Water and SAO ices comprise the remainder of these mixtures equally.

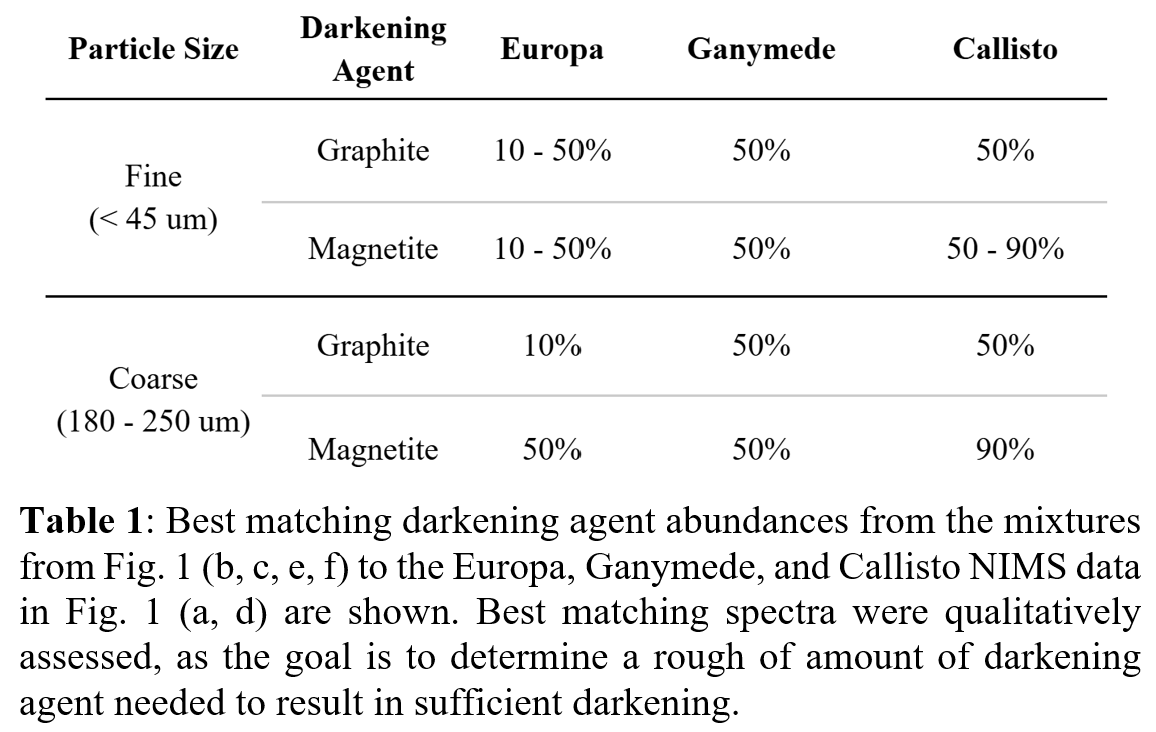

The fine and coarse darkening agent mixtures suggest a few wt.% darkening agents may not cause drastic overall darkening. Darkening by graphite is more efficient than magnetite at similar abundances, with total saturation being achieved at ~50% graphite compared to 90% magnetite. These mixtures are compared to the NIMS reflectance spectra shown in Fig. 1a, 1d to determine rough abundance estimates for the amount needed to match NIMS spectra (see Table 1, which displays the best matching abundance value).

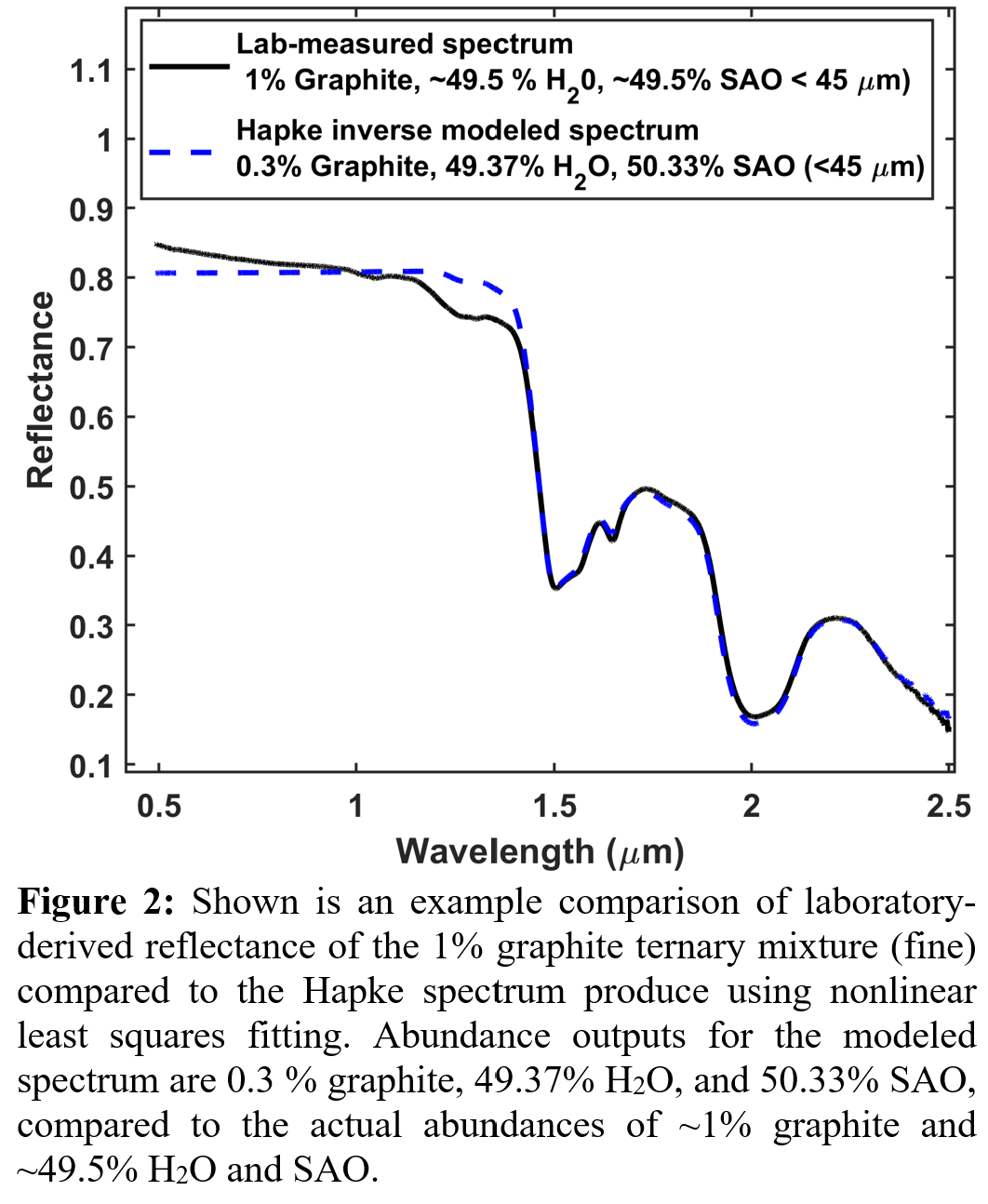

Hapke radiative transfer modeling [9] was used to produce spectra of each mixture to investigate model accuracy and limitations. Figure 2 shows a comparison of the 1 wt.% fine graphite mixture to a modeled spectrum produced by a nonlinear least square fitting algorithm to the Hapke reflectance equation. The best-fitting model spectrum used 0.3% graphite (45 μm), 49.37% water (36 μm), and 50.33% sulfuric acid octahydrate (45 μm).

Discussion:

Definitive statements about upper and lower limits of darkening agents through comparisons between NIMS data and lab mixtures (Table 1) are difficult to make. The surfaces of these bodies are undoubtedly more complex than simple three-component mixtures. However, we can still draw rough conclusions based on darkening agent abundances that give similar reflectance levels, despite not being able to match features perfectly.

Europa’s spectrum is closest to the 10 and 50 wt.% graphite and magnetite mixtures at fine and coarse particle sizes. For graphite, 10 wt.% is within previous darkening agent abundance estimates, but 50 wt.% of either graphite or magnetite is much higher than any reported darkening agent abundance. Ganymede’s spectra fall within expected ranges, suggesting that the darkening agent on Ganymede may be graphite, magnetite, both, or a similar material. At fine and coarse sizes, 50 wt.% magnetite is close to a lower limit of needed darkening agent abundance, as the Ganymede spectrum is darker by ~0.05. However, 90 wt.% graphite may serve as an upper limit, as the 90 wt.% mixture is darker than the Ganymede spectrum. An upper limit for magnetite or graphite of either particle size may be near 90 wt.% for Callisto.

Mixture results additionally highlight the overall plausibility of some darkening agents. For example, fine and coarse magnetite abundances need to be near 90 wt.% to match Callisto’s surface in some regions. Our mixtures may be spectrally similar to the Callisto spectrum; however, this is likely not representative of Callisto’s actual surface composition. The main avenue by which magnetite, or any Fe-rich material, can be delivered to Callisto’s surface is through (micro)meteorite impacts. A significant flux of Fe-rich impactors needed to have been present near Callisto to provide this amount. Graphite or C-bearing materials are more feasible. They can be delivered via (micro)meteorite bombardment, produced through radiolytic breakdown of surface C materials like CO2, or may also be sourced endogenically like on Europa, where CO2 signatures are linked to chaos terrain [10].

Laboratory mixtures were compared against Hapke modeled spectra to probe model limitations, especially in mixtures of very bright and very dark materials. More work needs to be done, but Figure 2 suggests the Hapke model struggles to reproduce visible wavelengths when the reflectance of bright materials is near unity. Figure 1 disagrees with the longstanding notion that a few wt.% dark materials can significantly darken bright materials when mixed. The agreement between Hapke-derived abundance with the actual abundances used in each mixture suggest this idea may not be true when the materials being mixed are at opposite reflectance extrema.

References:

[1] Strazzulla, G., et al., (2023). Earth Moon Planets 127, 2. [2] Carlson, R. W., et al., (1999) Science 286, 97-99. [3] Carlson, R. W., et al. (2002) Icarus 157, 456-463. [4] Dalton III, J. B., et al. (2013) Pl and Sp. Sci 77, 45-63. [5] Ligier, N., et al. (2019). Icarus 333, 496-515. [6] Tosi, F., et al. (2023) Nature Ast. 8, 82-93. [7] Ligier, N., et al. (2019). EPSC 13, 492-2. [8] Clark, C. (1982) Icarus 49, 244-257. [9] Hapke, B. (1981) JGR: Solid Earth 86, B4, 3039-3054. [10] Trumbo, S., et al., (2023) Science 381, 1308-1311.

How to cite: Hayes, T. and Li, S.: Constraining possible darkening agents on the surfaces of the icy Galilean moons, EPSC-DPS Joint Meeting 2025, Helsinki, Finland, 7–12 Sep 2025, EPSC-DPS2025-1097, https://doi.org/10.5194/epsc-dps2025-1097, 2025.