- 1Division of Geological & Planetary Sciences, California Institute of Technology, Pasadena, CA

- 2Space Studies Department, Southwest Research Institute, Boulder, CO

- 3Department of Earth and Planetary Sciences, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA

- 5NASA Jet Propulsion Laboratory, Pasadena, CA

- 6Laboratory for Atmospheric and Space Physics, University of Colorado, Boulder, CO

- 7NASA Ames Research Center, Space Science and Astrobiology Division, Moffett Field, CA

- 8Bay Area Environmental Research Institute, Moffett Field, CA

The New Horizons flyby of Pluto mapped temperature profiles, vertical profiles of N2, CH4, C2H2, C2H4, C2H6, and the vertical profile of hazes in Pluto’s atmosphere [1]. Zhang et al. 2017 showed that Pluto’s hazes can explain the colder-than-predicted upper atmosphere [2]. Previous stellar occultations reported large changes in haze optical depths on timescales of a few years. The observed presence and variability of hazes in Pluto’s atmosphere and its impact on the atmosphere motivates this work. We used KINETICS, a 1-D photochemical model and PlutoCARMA, a microphysical transport model, to study how Pluto's atmosphere responds to changes in solar UV flux. We simulated two scenarios (a sudden turn-on of a solar flare and a sudden transition from a solar minimum to solar maximum) with KINETICS to investigate formation and destruction timescales and abundances for species expected to be present in Pluto's atmosphere. Cation reactions were added to KINETICS, resulting in a substantial decrease (up to 5x) of certain C2Hx production rates at high altitudes compared to a neutrals-only case.

The main means of formation for all haze precursor species originates with photodestruction of and reactions involving CH4. These form CH3, 1CH2, and C2H4 in roughly equal amounts. CH3 forms HCN and C2H6, C2H4 forms C2H2, and the majority (> 90%) of 1CH2 eventually forms the methylidyne radical (CH) which is free to react with anything in the atmosphere. Reaction of the methylidyne radical with methane is responsible for > 90% of C2H4 production. C2H4 either reacts with CH or photodissociates to form C2H2, which is the major chemical bottleneck for production of the other species. C2H2 is the predecessor of several other haze precursor reactions, notably C8H2 (for which we observe one of the greatest increases in mixing ratio in response to a change in solar flux), HCN, C4H2, and HC3N. C2N2, another species which observes a dramatic increase in mixing ratio, forms mainly (>90% of production) from the reaction CN + HNC.

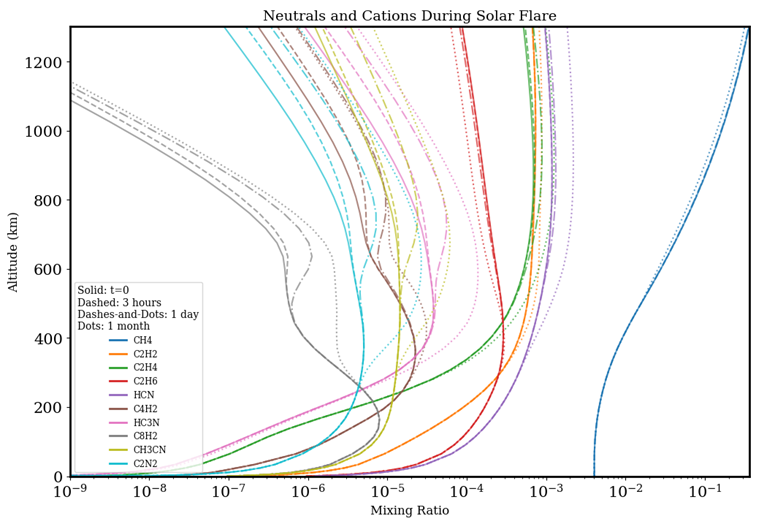

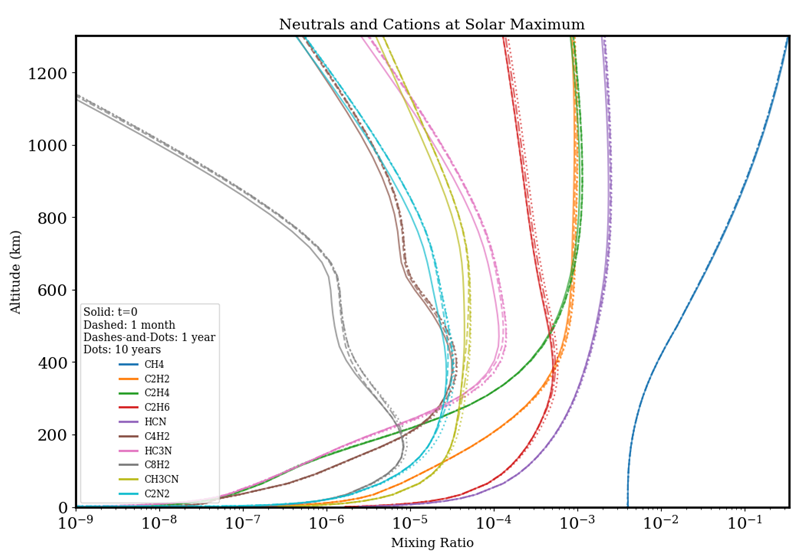

KINETICS simulations show that photochemical formation of haze precursors occurs on timescales of hours during a solar flare and months during a solar maximum. PlutoCARMA simulations demonstrate settling timescales of several days for micron-size particles. The mixing ratio of key haze precursors at certain times is shown in Fig. 1. These results suggest that photochemical changes to haze opacity will not be detected on solar flare timescales but could be detectable over an 11-year solar cycle. The high haze optical depths were measured in 2002 by ground-based observation and in 2015 during New Horizons’ flyby, i.e., at a time close to the peaks of the 23 and 24 solar cycles. This correlation between haze opacity and solar cycle was one of the motivations for this work. Results from KINETICS simulations show that some haze precursor species are created or destroyed in significant amounts on timescales that are shorter than a solar cycle, but the simulations do not match the amplitude of τHAZE change measured between 2002 and 2007 (at least a 30x decrease) or between 2007 and 2015 (at least a 2.8x increase) [3]. In other words, photochemistry due to changing solar UV flux cannot be the sole explanation for the changes in haze optical depths that have been observed from occultations.

Fig. 1a: mixing ratio of key haze precursors for the version of the model including neutrals and cations at key time steps run with flux associated with solar flare

Fig. 1b: mixing ratio of key haze precursors for the version of the model including neutrals and cations at key time steps run with flux associated with solar maximum

References:

[1] Young, L. A. et al. (2018) Icarus, 300, 174–199. [2] Zhang, X., Strobel, D. F., Imanaka, H. (2017). 551(7680), 352–355. [3] Young, E., Young, L., & Buie, M. (2023, October). Abstract presented at the 55th Annual Meeting of the Division for Planetary Sciences, Bulletin of the American Astronomical Society, 55(8), 308.03.

How to cite: Shawcross, J., Young, E., Adams, D., Yung, Y., Thiemann, E., Barth, E., Sciamma-O'Brien, E., and Dubois, D.: Response of Haze Precursors on Pluto to Solar Variability , EPSC-DPS Joint Meeting 2025, Helsinki, Finland, 7–12 Sep 2025, EPSC-DPS2025-1100, https://doi.org/10.5194/epsc-dps2025-1100, 2025.