- 1Université Paris Cité, Institut de Physique du Globe de Paris, CNRS, France (delaroque@ipgp.fr)

- 2Institute for Planetary Materials, Okayama University, Japan

- 3Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency, Japan

- 4University of Aizu, Japan

- 5Jet Propulsion Laboratory, California Institute of Technology, United-States

- 6Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory, United-States

The NASA Dragonfly mission, selected in 2019 as the 4th mission of the New Frontiers mission program, is set to explore Saturn's largest moon, Titan, in the mid-2030s [1]. Titan remains a prime target for astrobiological research due to its dense atmosphere, active organic chemistry, and suspected subsurface liquid ocean beneath an icy crust [2]. One of the Dragonfly’s key science goals is to detect potential biosignatures and to study the coupling between Titan’s internal, surface, and atmospheric layers through the characterization of the transport of materials across the entire body with the tectonic processes that might drive or influence this global circulation. To date, the composition and thickness of internal layers – the outer ice shell, global ocean, possible high-pressure ice phases, and silicate mantle – remain poorly constrained, limiting our understanding of Titan’s habitability potential [3,4].

To address this, the mission will carry the DraGMet SEIS instrument (uniaxial velocity-sensing short-period seismometer and 3-axis geophones mounted on each skid), designed to perform seismic measurements to probe Titan’s subsurface and deeper internal structure. Titan displays a wide variety of surface features, such as large equatorial dune fields [5], mountain chains [6], and impact craters [7], along with multiple lines of evidence of resurfacing processes [8,9], as documented by the Cassini-Huygens mission (2004–2017). These observations suggest ongoing internal and surface geological activity that could produce signals recordable by a single-station seismometer. Among the anticipated seismic sources, icequakes generated by tidal-induced stress are also expected to occur in icy satellite environments [10,11,12]. Our recent investigations focus on the detectability of seismic body wave reverberations of such events within the icy crust under realistic noise conditions, which includes updated experimental data on DraGMet short-period seismometers’ instrumental self-noise under cryogenic temperatures and models of environmental noise based on Titan’s atmospheric dynamics.

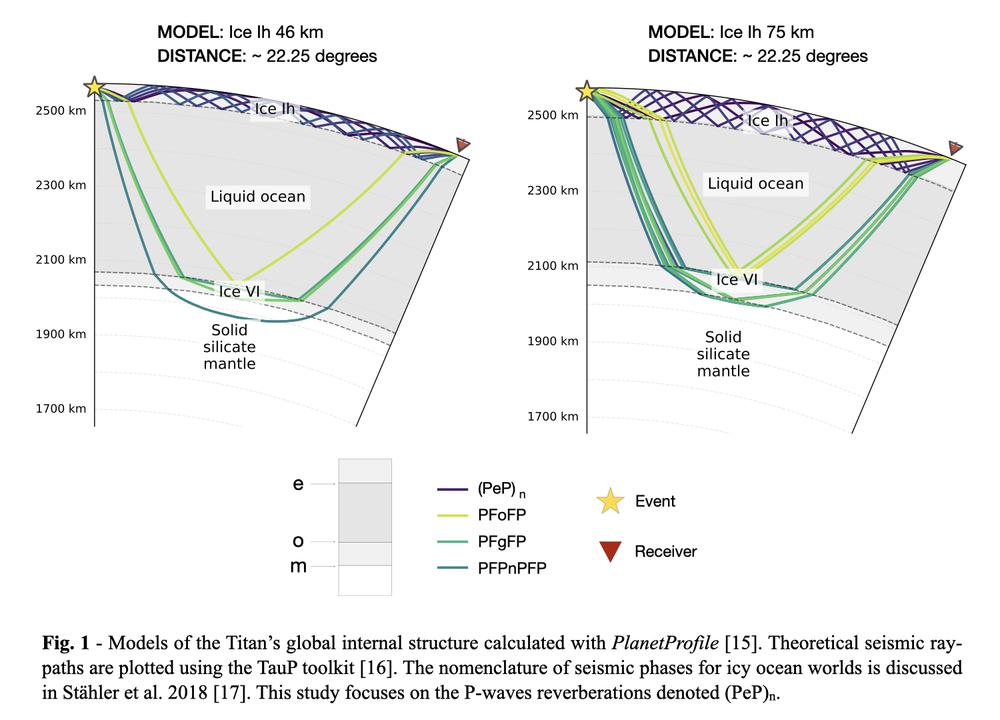

As a first step, we select a seismic source event whose source mechanism and location are consistent with diurnal tidal stress models and surface observations [13]. The event seismic magnitude is set to Mw 4.0, representing an end-member scenario consistent with predictions on Titan seismicity modeled with tidal dissipation energy budgets [14]. Given the uncertainty in ice thickness estimated to range between 50 and 200km [15], we also construct a suite of 1D self-consistent internal structures and anelastic attenuation scenarios, assuming a homogeneous outer water-ice shell (Figure 1).

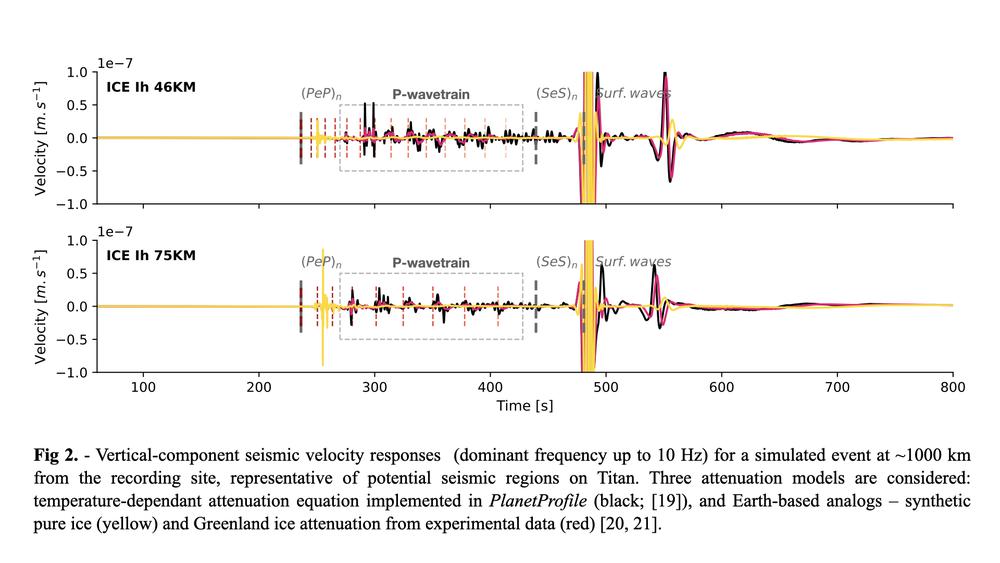

We simulate high-frequency waveforms with the wavenumber integration method of CPS (Computer Programs in Seismology; [18]), where results are displayed in Figure 2, and then compare the amplitude of the P-wavetrain window content with noise models in the spectral domain.

Atmospheric turbulence is considered as one of Titan's dominant environmental noise sources [22,23]. To enable direct comparisons with synthetic waveform amplitudes, the expected noise level range induced by atmospheric turbulence was modeled for two end-member surface conditions: a highly porous regolith-like material and a rigid icy substrate [24]. In the Fourier domain, environmental noise is predominant at high frequencies (i.e.,≥1Hz), whereas instrumental noise tends to dominate at lower frequencies.

Our results suggest that a Mw≥4.0 event, relatively strong and marginal on Titan, could be detectable within the frequency band where body waves dominate (i.e., 0.1–1Hz) under a low-attenuation scenario. Regardless of the attenuation model, detection becomes increasingly difficult at higher frequencies when the surface is poorly consolidated (i.e., analogous to Martian regolith), limiting the usable frequency range to around 2Hz, or even below 1Hz if the ice is highly attenuating. In the worst-case scenario, involving a thick and strongly attenuating ice shell, the amplitude of these phases is significantly reduced, severely hindering their detection even within the body-waves frequency band (Figure 2).

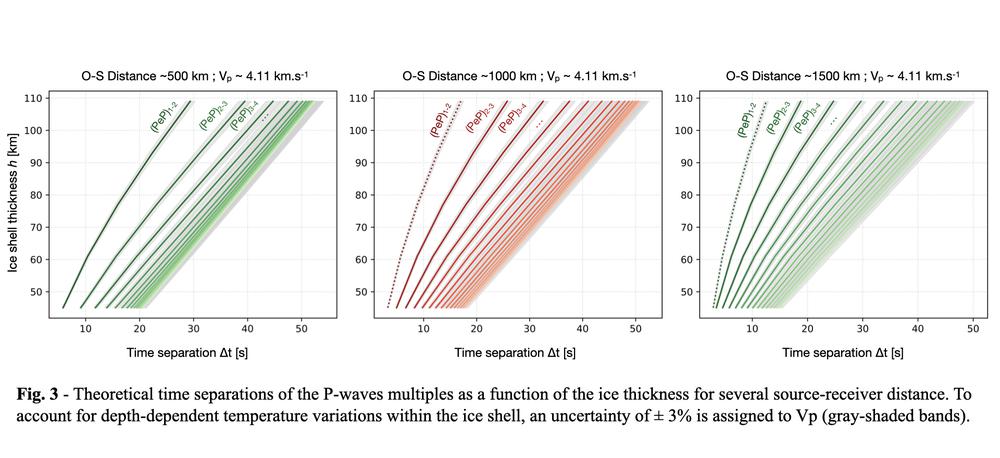

When multiples are detectable – for instance, during nearby events, strong enough magnitude, or in low-attenuation ice – reverberations can be used to estimate ice thickness. Assuming a uniform crustal thickness, the time separation between multiples can be directly linked to the ice thickness (see Figure 3). The picking of these multiples using this method is illustrated in Figure 2 with dashed-red lines.

References

[1] Barnes et al. (2021). Planet. Sci. J., 2, 130. [2] Iess et al. (2012). Science, 337, 457-459. [3] Vance et al. (2018). Astrobiology, 18, 37-53. [4] Marusiak et al. (2021). Planet. Sci. J., 2, 150. [5] Lorenz et al. (2006). LPSC XXXVII, abstract #1249. [6] Radebaugh et al. (2007). Icarus, 192, 77-91. [7] Wood et al. (2005). LPSC XXXVI, abstract #1117. [8] Tomasko et al. (2005). Nature, 438, 765-778. [9] Moore et al. (2011). Icarus, 212, 790-806. [10] Greenberg et al. (1998). Icarus, 135, 64-78. [11] Smith-Konter and Pappalardo (2008). Icarus, 198, 435-451. [12] Pappalardo et al. (1997). Icarus, 135, 276-302. [13] Burkhard et al. (2022). Icarus, 371, 114700. [14] Panning et al. (2021). SEG Techn. Progr., 3539-3542. [15] Vance et al. (2018). JGR: Planets, 123, 180-205. [16] Crotwell et al. (1998). Seism. Res. Lett., 70, 154-160. [17] Stähler et al. (2018). JGR: Planets, 123, 206-232. [18] Herrmann (2013). Seism. Res. Lett., 84, 1081-1088. [19] Cammarano et al. (2006). JGR: Planets, 111, E12009. [20] Kuroiwa (1964). Contrib. Inst. Low Temp. Sci., A18, 49-62. [21] Dapré and Irving (2024). Icarus, 408, 115806. [22] Jackson et al. (2020). JGR: Planets, 125, e2019JE006238. [23] Lorenz et al. (2021). Planet. Space Sci., 206, 105320. [24] Onodera et al. (2025). 56th LPSC, abstract #1145.

How to cite: Delaroque, L., Kawamura, T., Lucas, A., Rodriguez, S., Onodera, K., Shiraishi, H., Yamada, R., Tanaka, S., Panning, M., and Lorenz, R.: Preparing Dragonfly to Titan: Detection of Body Waves to Constrain Ice Shell Thickness, EPSC-DPS Joint Meeting 2025, Helsinki, Finland, 7–12 Sep 2025, EPSC-DPS2025-1311, https://doi.org/10.5194/epsc-dps2025-1311, 2025.