Multiple terms: term1 term2

red apples

returns results with all terms like:

Fructose levels in red and green apples

Precise match in quotes: "term1 term2"

"red apples"

returns results matching exactly like:

Anthocyanin biosynthesis in red apples

Exclude a term with -: term1 -term2

apples -red

returns results containing apples but not red:

Malic acid in green apples

hits for "" in

Network problems

Server timeout

Invalid search term

Too many requests

Empty search term

OPS5

Session assets

Introduction:

Titan's atmosphere features intricate chemical and meteorological dynamics, particularly the seasonal development of polar stratospheric clouds, which were extensively studied by the Cassini mission. These clouds were initially observed during the northern winter, completely covering the North Polar Region between 2004 and 2012 [1]. As Titan transitioned into northern spring, the northern cloud dissipated, and a similar cloud emerged over the South Pole from 2012 until the mission concluded in 2017 [2, 3, 4].

Spectroscopic analyses have revealed that these clouds are composed of various ices, including hydrocarbons such as C6H6, as well as nitriles like HCN [5, 2, 6].

Nevertheless, the full seasonal behavior of these polar clouds and the relationship between their northern and southern occurrences remain poorly understood. Key questions persist: What processes lead to their formation? How do their structure and composition evolve? Are the northern and southern clouds manifestations of a single overarching system? Is there an asymmetry between them? And what becomes of the condensed chemical species?

Results & Discussion:

To address these questions, we employ a microphysical cloud model that simulates key processes—nucleation, condensation, and sublimation—for six primary species involved in Titan’s cloud dynamics: CH4, C2H2, C2H6, C6H6, HCN, and HC3N. This model is integrated with the Titan Planetary Climate Model (Titan PCM) [7, 8], which provides atmospheric constraints and simulates three-dimensional transport and mixing.

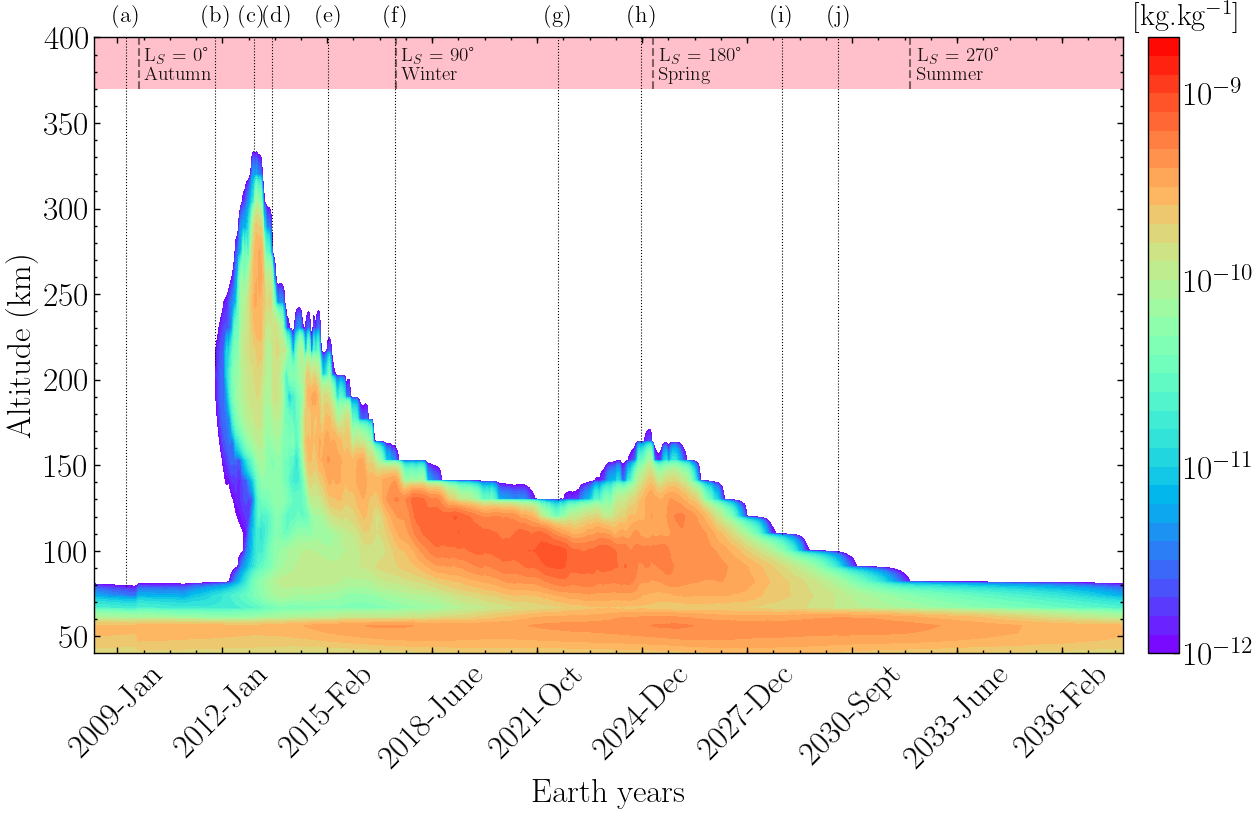

Our simulations indicate that Titan's polar clouds begin forming in early autumn at altitudes around 330 km, confined within the polar vortex, triggered by pronounced stratospheric cooling and a buildup of trace gases driven by the planet's general circulation (Figure 1). During autumn and winter, the clouds undergo significant evolution in altitude, extent, and composition. Enhanced atmospheric subsidence during late autumn causes the cloud layer to descend to below 160 km and spread horizontally to about 59° latitude. By late winter, the cloud reaches a final development phase before fully dissipating roughly four years after the spring equinox, driven by warming in the stratosphere and depletion of condensable species in the polar region.

Figure 1. Vertical evolution of the mass mixing ratio of ices at Titan’s South Pole (> 60°S) in the Titan PCM. Vertical lines correspond to key phases in the polar cloud’s evolution.

While these clouds facilitate the formation of ices in Titan’s lower atmosphere, their surface precipitation rates remain minimal compared to that of methane. Due to their high-altitude origin, most of the cloud particles re-evaporate before reaching the surface.

We will present Titan’s polar cloud cycle, the observed variations in altitude and composition between early autumn and late winter, as well as the connection between the clouds observed in the northern and southern hemispheres.

References: [1] Le Mouélic et al (2012) Planet. Space Sci., 60, 1. [2] de Kok et al (2014) Nature, 514, 7520. [3] West et al (2016) Icarus, 270. [4] Le Mouélic et al (2018) Icarus, 311. [5] Griffith et al (2006) Science, 313, 5793. [6] Vinatier et al (2018) Icarus, 310. [7] de Batz de Trenquelléon et al (2025a) Planet. Sci. J., 6, 4. [8] de Batz de Trenquelléon et al (2025b) Planet. Sci. J., 6, 4.

How to cite: de Batz de Trenquelléon, B., Rannou, P., Vinatier, S., and Lebonnois, S.: Complex Seasonal Cycle of Titan's Polar Clouds, EPSC-DPS Joint Meeting 2025, Helsinki, Finland, 7–13 Sep 2025, EPSC-DPS2025-1312, https://doi.org/10.5194/epsc-dps2025-1312, 2025.

Titan's atmosphere is mainly composed of nitrogen and methane. The solar flux triggers complex photochemical reactions that produce organic compounds, leading to the formation of photochemical aerosols. Further down in the atmosphere, temperatures drop sufficiently to allow the photochemical species to condense on the surface of the aerosols and form clouds. Titan is subject to strong seasonal variations due to its inclination, resulting in a global circulation that generates dynamics from the deep stratosphere to the mesosphere [1].

Many studies based on Cassini observations show the spatial and temporal evolution of cloud formation on Titan as a consequence of seasonal variations [2,3]. Data from the Visible and infrared mapping spectrometer (VIMS) on board Cassini, were used to study the seasonal changes that occur between the two poles. The polar cloud observed in the north during winter gradually disappears, only to reappear in the south during spring in the north [4]. The location at which species condense depends on their abundance and the temperature profile. For different times and locations, changes in the temperature and the transport of photochemical species by the meridional circulation allow some species to condense at different altitudes. The formation of HCN and C6H6 clouds has been observed between 250 and 300 km at the South Pole after the equinox [5,6,7], when a high concentration of gaseous species is observed, which may explain the cooling required to form clouds at these altitudes. Hanson et al. 2023 [8] demonstrated through a 1D simulation the formation of HCN clouds near 300 km and descends to the lower stratosphere followed by precipitation to the surface. Batz de Trenquelléon et al. 2025 [9] obtained results on the formation of winter polar clouds from 60 to 300 km after enrichment with trace compounds using the Titan Planetary Climate Model (3D model).

Here we advance further on the details of the interplay between gases, haze and clouds, by investigating the condensation of all major gases in Titan’s atmosphere. We use a 1D numerical model previously applied to Titan and Pluto [10,11], which combines radiative transfer, photochemistry, microphysical evolution of haze and clouds, condensation and nucleation. The model also takes into account atmospheric mixing, molecular diffusion, particle sedimentation and diffusion. Primary particles form in the upper atmosphere and then coagulate to form aggregates. The growth mode of settling haze particles is controlled by the fractal dimension of the aerosol. Cloud particle formation is initiated by heterogeneous nucleation of gas on a haze particle under supersaturated conditions. We introduce 23 gaseous species into cloud formation. The rates of condensation and evaporation are given by the mass flux of condensing species into and out of the particle surface.

We first demonstrate the validity of the model used at the equator, where more observational constraints for hazes and clouds are available for gas abundances and optical properties. We will then present the results of the simulation at the South Pole, during the post-equinox period, where we compare the evolution of the condensation of gaseous species and the haze and cloud profiles with equatorial conditions. To account for the photochemical and haze particle enrichment occurring at the South Pole post-equinox, we incorporate a circulation contribution, derived from observations, into our model. This addition contributes significantly to the observed mass of chemical species and haze particles involved in cloud formation. We further validate the model using the Composite Infrared Spectrometer (CIRS) observations of gas abundance and haze abundance & extinction.

[1] de Batz de Trenquelléon, B., Rosset, L., Vatant d’Ollone, J., et al. The New Titan Planetary Climate Model. I. Seasonal Variations of the Thermal Structure and Circulation in the Stratosphere, PSJ, 6, 78 (2025). https://doi.org10.3847/PSJ/adbbe7

[2] R.A. West, A.D. Del Genio, J.M. Barbara, D. Toledo, P. Lavvas, P. Rannou, E.P. Turtle, J. Perry, Cassini Imaging Science Subsystem observations of Titan’s south polar cloud, Icarus, Volume 270, 2016, Pages 399-408, ISSN 0019-1035, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.icarus.2014.11.038.

[3] S. Vinatier, B. Schmitt, B. Bézard, P. Rannou, C. Dauphin, R. de Kok, D.E. Jennings, F.M. Flasar, Study of Titan’s fall southern stratospheric polar cloud composition with Cassini/CIRS: Detection of benzene ice, Icarus, Volume 310, 2018, Pages 89-104, ISSN 0019-1035, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.icarus.2017.12.040.

[4] S. Le Mouélic et al. Mapping polar atmospheric features on Titan with VIMS: From the dissipation of the northern cloud to the onset of a southern polar vortex, Icarus, Volume 311, 2018, Pages 371-383, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.icarus.2018.04.028.

[5] Teanby, N. A., Sylvestre, M., Sharkey, J., Nixon, C. A., Vinatier, S., & Irwin, P. G. J. (2019). Seasonal evolution of Titan's stratosphere during the Cassini mission. Geophysical Research Letters, 46, 3079–3089. https://doi.org/10.1029/2018GL081401

[6] de Kok, R., Teanby, N., Maltagliati, L. et al. HCN ice in Titan’s high-altitude southern polar cloud.Nature 514, 65 - 67 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1038/nature13789

[7] Vinatier, S. et al. Seasonal variations in Titan’s middle atmosphere during the northern spring derived from Cassini/CIRS observation. Icarus, Volume 250 (2015), Pages 95-115, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.icarus.2014.11.019.

[8] Hanson, L. E., Waugh, D., Barth, E., & Anderson, C. M. Investigation of Titan’s South Polar HCN Cloud during Southern Fall Using Microphysical Modeling, PSJ, 4, 237 (2023). https://doi.org//10.3847/PSJ/ad0837

[9] Bruno de Batz de Trenquelléon et al. The new Titan Planetary Climate Model. II. Titan’s Haze and cloud cycles. Planet. Sci. J. 6 79 (2025). https://doi.org/10.3847/PSJ/adbb6c

[10] P. Lavvas, C.A. Griffith, R.V. Yelle, Condensation in Titan’s atmosphere at the Huygens landingsite,Icarus,Volume215,Issue2,2011,Pages732-750. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.icarus.2011.06.040.

[11] Lavvas, P., Lellouch, E., Strobel, D.F. et al. A major ice component in Pluto’s haze. Nat Astron 5,289–297 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41550-020-01270-3

How to cite: Damiens, A. and Lavvas, P.: Simulation of the interplay between haze and clouds at equatorial and polar conditions of Titan's atmosphere, EPSC-DPS Joint Meeting 2025, Helsinki, Finland, 7–13 Sep 2025, EPSC-DPS2025-279, https://doi.org/10.5194/epsc-dps2025-279, 2025.

Titan is the largest moon of Saturn, with a radius around 2575 km, and it is surrounded by a thick atmosphere composed of nitrogen, methane, and many other organic compounds. The temperature and pressure profiles on Titan enable the condensation of several gases in the atmosphere, including methane, forming clouds. Here we focus on the methane clouds.

Titan has been observed up close during the Cassini mission, between 2004 and 2017. Some of the methane clouds observed then seem convective (see Figure 1 for an example). We want to reproduce these clouds in a numerical model, to try to answer some of these questions:

- what are the conditions that enable convective methane clouds on Titan? (temperature, methane concentration, global scale influence, topography, ...)

- do we form shallow convection? deep convection?

- how does convection organize itself on Titan?

- what is the size of the cloud particles?

- how do the scales of the convective systems on Titan and on Earth relate?

Figure 1 : Tropospheric methane clouds over the south pole of Titan, July 2004 (Cassini/ISS, infrared filters). The cloud diameter is around 500 km.

To tackle these questions, we need a mesoscale model of Titan's atmosphere, i.e. a local model (approximately above a 100 km zone). The current Titan mesoscale model used at LMD couples the physics of the Titan-PCM model (Trenquelléon et al. 2025a) with the dynamics of the WRF model (a weather forecasting model also used for Earth previsions), see for instance Lefevre, Bonnefoy, and Spiga 2024. In our study, we include the new microphysics modules (i.e. the aerosols and clouds modules, described in Trenquelléon et al. 2025b) and use the last version of WRF (WRF-V4). The microphysics schemes we use enable to study the formation of cloud particles, and their size distribution. We use a horizontal resolution of a few kilometers: this enables us to resolve the clouds, i.e. to consider each grid cell to be either completely a cloud or completely clear, without subcell cloud parameterization. Such a model is called a cloud resolving model. For Titan, several cloud resolving models have been developped (Hueso and Sánchez-Lavega 2006, Barth and Rafkin 2010), based on other dynamical cores and physical schemes.

Our first test cases are a "warm bubble" and a "cold bubble", over a very small domain (40x40 km, the top of the model is 30 km high). Such simulations are useful to check the behavior of the model. We obtain respectivelly a rising and a falling air parcel, with for each case methane condensation (when the air reaches colder atmospheric layers for the warm bubble case, and due to low temperatures in the bubble for the cold bubble case).

Our next steps will be to perform more testing (e.g. abundant methane zone). Then, we will study the different formation mechanisms for clouds (in particular convective clouds): solar heating, topographic clouds, methane accumulation due to the global circulation, lake evaporation, ... We will try to explore the parallels and discrepancies between Earth's water convective clouds and Titan's methane convective clouds.

References

Barth, Erika L. and Scot C. R. Rafkin (Apr. 1, 2010). “Convective cloud heights as a diagnostic for methane environment on Titan”. In: Icarus. Cassini at Saturn 206.2, pp. 467–484. issn: 0019-1035. doi: 10.1016/j.icarus.2009.01.032. url: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0019103509000591

Hueso, R. and A. Sánchez-Lavega (July 2006). “Methane storms on Saturn’s moon Titan”. In: Nature 442.7101. Number: 7101 Publisher: Nature Publishing Group, pp. 428–431. issn: 1476-4687. doi: 10.1038/nature04933. url: https://www.nature.com/articles/nature04933

Lefevre, Maxence, Léa Bonnefoy, and Aymeric Spiga (July 3, 2024). Mesoscale Modelling of Titan’s Shangri-La region. doi: 10.5194/epsc2024-408. url: https://meetingorganizer.copernicus.org/EPSC2024/EPSC2024-408.html

Trenquelléon, Bruno de Batz de et al. (Mar. 31, 2025a). “The New Titan Planetary Climate Model. I. Seasonal Variations of the Thermal Structure and Circulation in the Stratosphere”. In: The Planetary Science Journal 6.4. Publisher: IOP Publishing, p. 78. issn: 2632-3338. doi: 10.3847/PSJ/adbbe7. url: https://iopscience.iop.org/article/10.3847/PSJ/adbbe7/meta

Trenquelléon, Bruno de Batz de et al. (Mar. 31, 2025b). “The New Titan Planetary Climate Model. II. Titan’s Haze and Cloud Cycles”. In: The Planetary Science Journal 6.4. Publisher: IOP Publishing, p. 79. issn: 2632-3338. doi: 10.3847/PSJ/adbb6c. url: https://iopscience.iop.org/article/10.3847/PSJ/adbb6c/meta

How to cite: Moisan, E., Spiga, A., and Chatain, A.: Developping a new cloud resolving model for Titan’s methane clouds, EPSC-DPS Joint Meeting 2025, Helsinki, Finland, 7–13 Sep 2025, EPSC-DPS2025-1616, https://doi.org/10.5194/epsc-dps2025-1616, 2025.

We analyzed 16,000 Cassini ISS (Imaging Science Subsystem) images of Titan in the 935 nm CB3 filter. The apparent changes during the 13-years of observations are a complex superposition of atmospheric changes, changes due to geometry, and physical surface changes. Because atmospheric changes dominate and the signal from the surface is attenuated by the atmosphere by about two orders of magnitude, the signal from the surface in single images is too noisy to allow detection of surface changes, except for the largest ones that have been published.

However, when stacking hundreds or thousands of images, good signal-to-noise ratios can be restored, but the challenge lies in the accuracy of stacking since surface data are influenced by the changing atmosphere. We tried to account for atmospheric effects that create shifts, smear, and attenuation.

Once we use all 16,000 suitable ISS images for stacking, we find that low-contrast surface changes show a richness of types of changes, yet most of them have the same temporal variability: features stayed constant from 2004 to 2010 and from 2011 to 2017, but changed significantly between both periods. Three examples are displayed in Fig. 1. The data are consistent with a sudden change in September 2010, which corresponds to the time of the strongest storm observed during the Cassini period (https://www.nasa.gov/image-article/titans-arrow-shaped-storm/). Detected surface changes extend over essentially all longitudes and most latitudes that were observed both before and after 2010. This suggests that the September 2010 storm may have caused global resurfacing on Titan.

We will archive our image products on the Imaging PDS in 2026. We plan to archive one set of 16,000 images that shows each original ISS image in about six versions and projections. We also plan to archive on the order of 100 global mosaics for different time periods so that the timing of detected surface changes can be constrained.

This work was supported by NASA grant 80NSSC21K0866.

Fig. 1: The evolution of three selected areas as seen by ISS from 2004 to 2017, centered on 280W 28N (left), 85W 34N (center), and 278W 19S (right), each 1500 km wide. The color panel at the top shows average images 2004-2010 in blue and 2011-2017 in orange. Blue and orange areas indicate decreasing and increasing albedo, respectively. The left panel shows a very dark area with a dark streak toward the northeast until 2010 and toward the north afterwards. Apparent variations within both time periods may be due to variation in data quality. The center panel shows the appearance of a bright streak after 2010 that varied and moved. The right panel shows a region with many changed features between both time periods. Also, the 2004 image appears to be significantly different from the images 2005-2010. Note that imperfect calibration can change brightness and contrast, but not the shape of features.

How to cite: Karkoschka, E., Archinal, B., and Weller, L.: Archiving Titan's surface changes: the global change in 2010, EPSC-DPS Joint Meeting 2025, Helsinki, Finland, 7–13 Sep 2025, EPSC-DPS2025-40, https://doi.org/10.5194/epsc-dps2025-40, 2025.

Understanding Titan’s Planetary Boundary Layer (PBL)—the lowest part of the atmosphere directly influenced by surface conditions—remains challenging due to Titan’s dense atmosphere and limited direct observations. Previous modeling efforts have produced a wide range of estimates for surface temperature and PBL behavior, particularly regarding diurnal variations, but have not clearly examined how subsurface parameters—specifically thermal conductivity, volumetric heat capacity, and their combined effect as thermal inertia—influence these outcomes. In this study, we revisit this issue using the Titan Atmospheric Model (TAM), a General Circulation Model (GCM) specifically developed for Titan (Lora et al. 2015; Lora 2024). Alongside, we present a theoretical framework that links the surface temperature variations to surface energy balance, providing a physically grounded interpretation of the simulation results.

First, we present simulation results under a dry setup to allow direct comparison with previous studies. Our theoretical framework explains the weak sensitivity of seasonal surface temperature structure to local thermal inertia, as reported by MacKenzie et al. (2019), who applied a global thermal inertia map to a GCM. This insensitivity arises from the minimal role of subsurface heat conduction in modulating surface temperature over Titan’s long annual cycle, where atmospheric damping is the dominant control. In contrast, at diurnal timescales, subsurface heat conduction plays a more significant role than atmospheric damping. As a result, diurnal surface temperature variations become sensitive to local thermal inertia, reaching magnitudes on the order of O(10-1) [K] near the equator during midsummer. Specifically, high thermal inertia surfaces (Hummocky terrain: 1,962 [TIU]; TIU is Thermal Inertia Unit [J•m-2•s-0.5•K-1]) exhibit variations of approximately 0.1 [K], while low thermal inertia surfaces (Dunes: 246 [TIU]) show variations of up to 0.4 [K]. These thermal differences influence PBL structures as well: larger temperature amplitudes lead to higher daytime maximum surface temperatures, which in turn result in deeper adiabatic layers, increasing the PBL depth by several hundred meters to over 1,000 meters. These findings support the interpretation of the Huygens data as capturing the diurnal evolution of the PBL during the local morning (Charnay and Lebonnois, 2012).

Furthermore, we investigate the role of Titan’s methane cycle in shaping PBL structure. Our simulations show that including the methane cycle reduces the equator-to-pole temperature gradient, improving agreement with observational constraints and highlighting the importance of latent heat, consistent with previous studies (e.g., Mitchell et al., 2009; Lora and Adamkovics, 2017). The simulations also produce a nearly constant methane mole fraction up to 5 km near the equator throughout the year, corresponding to the model’s simulated lifting condensation level. This result aligns with the Huygens probe observations of a constant methane humidity layer up to 5 km (Niemann et al., 2005; 2010). These findings underscore the importance of incorporating Titan’s methane cycle for realistic simulations of surface temperature and PBL dynamics.

References:

Charnay, B., & Lebonnois, S. (2012). Two boundary layers in Titan’s lower troposphere inferred from a climate model. Nature Geosci., 5 , 106–109.

Lora, J. M., Lunine, J. I., & Russell, J. L. (2015). GCM simulations of Titan’s middle and lower atmosphere and comparison to observations. Icarus, 250 , 516–528

Lora, J. M., & Adamkovics, M. (2017). The near-surface methane humidity on Titan. Icarus, 286 , 270–279.

Lora, J. M. (2024). Moisture transport and the methane cycle of Titan’s lower atmosphere. Icarus, 422 , 116241.

MacKenzie, S. M., Lora, J. M., & Lorenz, R. D. (2019). A thermal inertia map of Titan. J. Geophys. Res. Planets, 124 , 1728–1742.

Mitchell, J. L., Pierrehumbert, R. T., Frierson, D. M. W. & Caballero, R. (2009). The impact of methane thermodynamics on seasonal convection and circulation in a model Titan atmosphere. Icarus, 203, 250-264.

Niemann, H. B. et al. (2005). The abundances of constituents of Titan's atmosphere from the GCMS instrument on the Huygens probe. Nature, 438, 779-784.

Niemann, H. B. et al. (2010). Composition of Titan's lower atmosphere and simple surface volatiles as measured by the Cassini-Huygens probe gas chromatograph mass spectrometer experiment. J. Geophys. Res., 115, E12006.

How to cite: Han, S. and Lora, J.: Diurnal and Seasonal Variations of Titan’s Surface Temperature and Planetary Boundary Layer Structure Simulated with Dry and Moist GCMs, EPSC-DPS Joint Meeting 2025, Helsinki, Finland, 7–13 Sep 2025, EPSC-DPS2025-1087, https://doi.org/10.5194/epsc-dps2025-1087, 2025.

Please decide on your access

Please use the buttons below to download the supplementary material or to visit the external website where the presentation is linked. Regarding the external link, please note that Copernicus Meetings cannot accept any liability for the content and the website you will visit.

Forward to presentation link

You are going to open an external link to the presentation as indicated by the authors. Copernicus Meetings cannot accept any liability for the content and the website you will visit.

We are sorry, but presentations are only available for users who registered for the conference. Thank you.

Introduction:

The Cassini mission has observed surface changes that may represent the formation and dissipation of ephemeral lakes, i.e., transient lakes that dry-up on a geologically short timescale. As with ephemeral lakes on Earth, Titan’s ephemeral lakes result from the interaction of a generally arid climate with the variability of annual weather. Understanding the physics of ephemeral lakes will provide insight into the local, arid hydrological (methanological) cycle on Titan.

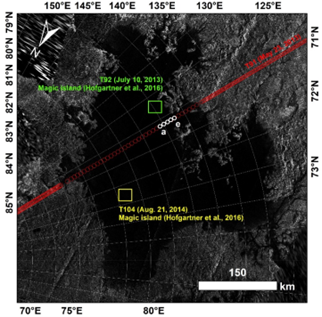

We have limited observations of the formation and dissipation of ephemeral lakes on Titan. Our best evidence is for two events: astorm and related ponding of liquid methane on the equator and the formation of a lake in the Arrakis Planitia region. Here we focus on the ephemeral lake in Arrakis Planitia, with particular interest in the mechanisms for the removal of the lake.

Arrakis Planitia Observations:

The formation of an ephemeral lake at Arrakis Planitia began in 2004. From 2004 to 2005, the Imaging Science Subsystem on the Cassini Mission along with a handful of ground-based telescopes observed both extensive cloud activity and darkening of the surface in the Arrakis Planitia region of Titan. Turtle et al. (2009) [1] identified darkening in Arrakis Planitia likely due to liquid methane rain produced by the storm seen in late 2004. The surface was observed to still be dark ∼9 months after the cloud activity [1,2], thus the presumed surface liquid remained at this time. By January 2007 (27 months after the cloud activity), the previously darkened region had brightened [2] however, there were at least some pockets of liquid standing on the surface in May 2007 (31 months after the cloud activity) as evidenced by specular reflections of sunlight observed by VIMS [2]. The darkening observed in Arrakis Planitia is in one region and corresponds with topography observed by the Cassini Synthetic Aperture Radar (SAR). The observations suggest that at least a few decimeters of liquid had pooled in this area.

Investigating the Evaporative Loss of the Ephemeral Lake:

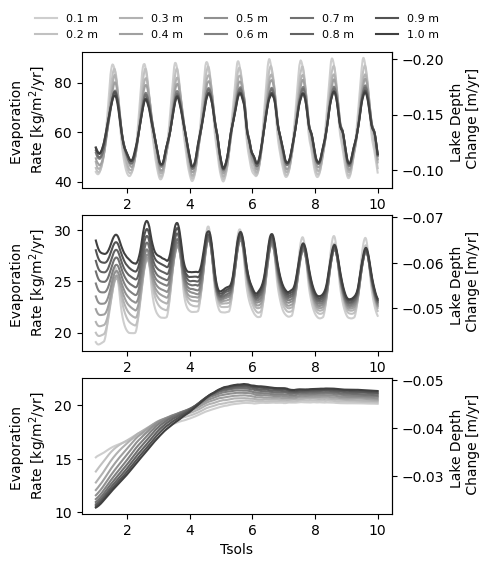

We created a map of Arrakis Planitia as the surface boundary condition for our simulations, which were conducted using the Mesoscale Titan WRF (mtWRF) model. We then integrated new estimates of the volume and longevity of the Arrakis Planitia ephemeral pond into mtWRF, and we simulated several ephemeral lake scenarios for Arrakis Planitia. The simulations were run for 10 tsols (i.e., Titan days), to allow the environment to reach a quasi-steady state.

With these simulations we estimated lake-scale evaporation rates and compared these rates with the observed surface changes. In Figure 1, we show the evaporation rate as a function of initial lake depth for three different Titan solar longitudes, that correspond to the beginning, middle, and end of the ephemeral lake. In each plot, the curves represent the average lake evaporation rate over multiple tsols, starting at the end of tsol 1. In the top row of Figure 1, the evaporation rate changes over a diurnal cycle. The simulation of Ls =142 (middle plot in Figure 1) is now further into southern winter, when the amount of insolation has begun to drop [3], and thus the evaporation rate has dropped by roughly half compared to the Ls = 305 evaporation rates. For the Ls = 35 simulations (bottom row of Figure 1), the diurnal cycle is completely gone. Instead, the evaporation of methane from the lake surface reaches a steady, day-long rate that is similar in magnitude to the nighttime evaporation rates seen in Ls = 305 simulations. This is what we expect for surface liquid methane in the polar south during the winter.

Rafkin et al., (2020) [4] have shown that convectively driven storms can form in the southern polar regions and can deposit up to 0.3 meters equivalent of methane rain over regions spanning 200 km. With pooling, it is possible to get ephemeral lake depths of a meter or greater. Thus, the delivery of methane rain and the range of lake depths that we have studied is consistent with modeling of storms on Titan.

For shallow lake depths, it may be possible for the ephemeral lake to disappear solely due to evaporation. Around 0.14 meters of liquid methane is evaporated per Earth year at the start of the ephemeral lake existence (i.e., 2005 or Ls = 305). Since most of the lake was gone by 2007 (Soderblom, 2024), two years later, an initial lake depth of roughly 0.3 meters could be removed in that time solely through evaporation. These estimates, however, are rather optimistic, since as time moves forward from 2005 to 2007, the evaporation rates over the lakes decreases. Deeper initial lakes, however, would also require infiltration of liquid methane to lower lake levels fast enough to match Cassini observations.

Conclusion:

Mesoscale modeling of the ephemeral lake at Arrakis Planitia demonstrates that evaporation may be able to completely remove the shallowest possible depths for this lake. A deeper lake, however, requires infiltration of methane liquid into the subsurface to explain the observed changes in the lake extent. Regardless, evaporation remains an important mechanism for the ephemeral lake evolution, particularly at the early stages of the lake’s existence, when the evaporation rates were double the rates experienced during polar night.

References:

[1] Turtle, E. P. et al. Cassini imaging of Titan’s high-latitude lakes, clouds, and south-polar surface changes. Geophys. Res. Lett. 36, L02204 (2009).

[2] A Soderblom, J.M., (2024) personal communication.

[3] Lora, J. M.. et al. Insolation in Titan’s troposphere. Icarus 216, 116–119 (2011).

[4] Rafkin, S. C. R. & Soto, A. Air-sea interactions on titan: Lake evaporation, atmospheric circulation, and cloud formation. Icarus 351, 113903 (2020).

How to cite: Soto, A., Soderblom, J., and Steckloff, J.: Potential Evaporation of Ephemeral Lakes on Titan, EPSC-DPS Joint Meeting 2025, Helsinki, Finland, 7–13 Sep 2025, EPSC-DPS2025-1096, https://doi.org/10.5194/epsc-dps2025-1096, 2025.

1. Introduction

Cassini’s RADAR altimetry data enabled the investigation of suspended particles and nitrogen gas bubbles in Titan’s hydrocarbon lakes and seas. These bodies, composed primarily of methane and ethane with dissolved nitrogen, may contain inclusions such as water ice, organic particles (e.g., tholins, nitriles), and nitrogen gas. Solid particles can originate from atmospheric haze, fluvial erosion, or precipitation, and may accumulate through sedimentation or surface runoff. Nitrogen bubbles are thought to form via supersaturation processes, triggered by temperature changes or increased ethane concentration during rainfall, leading to nitrogen exsolution and bubble formation near the seabed [1-3].

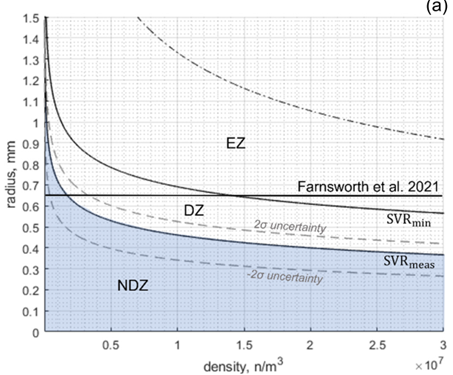

We present a methodology to constrain the size and density of both solid and gaseous inclusions using Cassini RADAR altimetric returns. A physical model based on Mie scattering and radiative transfer theory, compares modeled and observed surface-to-volume power ratios (SVR) to assess the inclusion detectability in Titan's liquid environments [4].

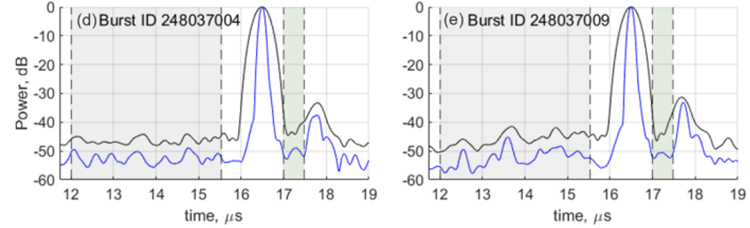

Figure 1. Selected bursts from T91 altimetric observation acquired by the Cassini RADAR.

2. Dataset, modelling and assumptions

We analyze altimetric data from the Cassini RADAR acquired at Ku-band (13.78 GHz, λ = 2.17 cm) acquired during fly-by T91 (Fig. 1). The data were processed using the Cassini Processing of Altimetric Data (CPAD), including incoherent averaging and range compression [5]. To enhance the nominal 35-m resolution, we applied super-resolution (SR) method based via Burg algorithm [6,7], improving surface/subsurface peak separation.

Nadir-looking radar observations in altimetry mode allow for the analysis of suspended inclusions in a homogeneous liquid medium. The received waveform enables surface, subsurface, and volume-scattered power measurement from which constrain inclusion size and density. With the objective of obtaining an expression for the Surface-to-Volume scattering power Ratio (𝑆𝑉𝑅), we model a liquid column containing uniformly distributed spherical particles and evaluate the volume backscattered power based on radiative equilibrium. Reflected and transmitted powers are defined using the surface Fresnel coefficient, dependent on the host dielectric constant, and a two-way transmissivity term. The total volume backscattering cross section includes both this transmissivity and the individual particle backscatter cross sections. Signal attenuation from particle scattering and absorption—mainly influenced by size and loss tangent—is also considered. The model assumes identical dielectric properties, no polarization or multiple scattering effects, and neglects shadowing, valid for particles smaller than the radar wavelength. The final expression, obtained for the case of a beam limited configuration, is

where 𝑃𝑆 and 𝑃𝑉 are the power reflected by the surface interface and through the volume respectively, 𝜎𝑜𝑉 and 𝑘𝑒 are the volume backscattering and extinction coefficients , 𝜃3,𝑑𝐵2 is the antenna beamwith at -3 dB, 𝑧1 and 𝑧2 are the integration depths [4].

Figure 2. Two of the selected altimetric observations acquired during fly-by T91 over Ligeia Mare, before and after super-resolution processing, in black and blue respectively. The area highlighted in green refers to the integrated waveform, while the gray one to the integrated noise.

3. Methodology and SVR Measurement

SVR was measured using T91 data over Ligeia Mare, where a consistent seabed echo was detected at approximately 160 m depth [5]. To improve seabed detectability, windowing has applied to the waveform, leading to degradation of the range resolution and limiting the available integration window. This required the application of super-resolution techniques to widen the final integration window between the surface and the subsurface, as shown in Fig.2.

The presence of volume scattering has then been evaluated by comparing the measured SVR with the integrated Signal-to-Noise Ratio (SNR𝑖𝑛𝑡). The measured volume power resulted falling between the integrated noise level across all observations, with lesser variation than 2-𝜎, indicating no clear evidence of volume scattering. Therefore, measured SVR served as an upper limit, constraining the possible size and density of inclusions. This upper bound defines a solution space where, for a given density, a maximum particle size is established—and vice versa—based on the modeled relationship between volume scattering and inclusion properties.

4. Results

Assumed a host medium composed of a liquid mixture of nitrogen-methane-ethane, with dielectric properties defined by a relative permittivity ε′ₕ = 1.72 and loss tangent tgδ = 3.5×10⁻⁵. Our analysis includes both suspended particles and nitrogen gas bubbles as potential inclusions. In Fig. 3, the measured SVR value of 45.92 dB delineates the boundary between two regimes: Non-Detection (ND) zone, where no volume scattering is observed, the Detection Zone (DZ), where scattering would be detectable by the radar, and an Extinction Zone (EZ), where excessive scattering or absorption would fully attenuate the signal, is also shown. By incorporating particle radius estimates from previous literature, the EZ allows us to define the maximum volume fraction at which inclusions become undetectable due to attenuation. Conversely, the DZ indicates the specific volume density required to match the measured SVR.

Figure 3. The figure shows the SVR derived from T91 Cassini RADAR data, modeled using a methane/ethane/nitrogen liquid host with nitrogen gas bubbles. The blue area represents combinations of particle size and density consistent with the absence of volume scattering. Horizontal lines indicate particle sizes from previous studies, while the black solid lines mark the measured SVR, setting upper limits on bubble density for a given size—or maximum size at varying densities.

For nitrogen-gas bubbles with radius of 0.65 mm from laboratory data, the maximum undetectable volume fraction was estimated at 0.19% [2]. For solid inclusions, the study found that particles smaller than approximately 0.34 mm (water ice), 0.5 mm (nitriles), and 0.84 mm (tholins) remain undetectable without causing extinction of the radar signal. Considering a realistic particle size range of 0.025–1.25 mm, the maximum detectable volume fractions were calculated to be 0.02%–3.49% for water ice, 0.03%–1.43% for nitriles, and 0.16%–1.52% for tholins. These results offer constraints on inclusions properties and inform detectability limits of radar systems, guiding future missions planning to Titan or similar icy moons [4].

References

[1] Barnes et al. 2011

[2] Farnsworth et al., 2019

[3] Cordier and Liger-Belair, 2018

[4] Gambacorta et al., 2024

[5] Mastrogiuseppe et al., 2014

[6] Raguso et al., 2024

[7] Gambacorta et al., 2022

How to cite: Gambacorta, L., Mastrogiuseppe, M., Carmela Raguso, M., Poggiali, V., Cordier, D., and Farnsworth, K. K.: Titan lakes and seas: estimation of nitrogen and solid particleS content via Cassini RADAR data, EPSC-DPS Joint Meeting 2025, Helsinki, Finland, 7–13 Sep 2025, EPSC-DPS2025-1891, https://doi.org/10.5194/epsc-dps2025-1891, 2025.

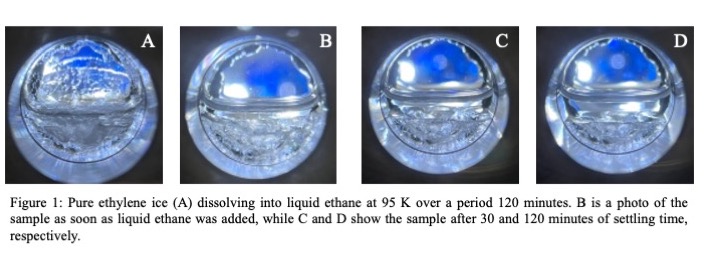

Titan is the only extraterrestrial environment known to support bodies of standing liquid on its surface. The Cassini mission provided important composition measurements of a few lakes and seas, which suggest they may contain anywhere from 5 - 80 % methane and 8 - 79 % ethane mixtures, in addition to dissolved nitrogen from the atmosphere. Cassini also measured trace amounts of higher-order hydrocarbons, such as propane, ethylene, and acetylene, in Titan’s atmosphere. When these trace species rain down onto the surface and mix with the lakes and seas, they create unique chemical conditions and alter the phase behavior, solubility, and stability of Titan’s surface liquids. In an effort to study these environments, we present our experimental work done in the Astrophysical Materials Lab at Northern Arizona University (NAU). We studied two different trace species, ethylene and acetylene, in methane-ethane mixtures under a nitrogen atmosphere of 1.5 bar to replicate Titan lakes. Specifically, we incorporated 1-10% additions of either ethylene or acetylene to the methane-ethane-nitrogen system and performed cooling and warming cycles of our sample between 70 - 100 K. Through a combination of visual inspection and Raman spectroscopy, we found that these mixtures undergo phase changes at different temperatures than their individual end members. The observed phase changes under these conditions have exciting implications for Titan’s lakes and seas, including compositional stratification of surface liquids, bubbles, and ice formation. We also measured the solubilities of both ethylene and acetylene in pure methane and pure ethane at 95 K. We will present the results of these experiments, in addition to thermodynamic models and how they relate to Titan environments.

This work was supported by NASA SSW grant 80NSSC21K0168, the John and Maureen Hendricks Foundation, and the Lowell Observatory Slipher Society.

How to cite: Thieberger, C., Hanley, J., Engle, A., Tan, S., Grundy, W., Lindberg, G., Steckloff, J., and Tegler, S.: Laboratory Experiments of Ethylene and Acetylene in Titan Lakes, EPSC-DPS Joint Meeting 2025, Helsinki, Finland, 7–13 Sep 2025, EPSC-DPS2025-1178, https://doi.org/10.5194/epsc-dps2025-1178, 2025.

The Saturnian system provides an example of a complex environment that includes a gas giant, numerous satellites and rings encompasses by a large magnetosphere. During its 13-year mission at Saturn from 2004-2017, the NASA provided numerous transformative observations and accumulated so much data that discoveries are still occurring from further analysis. These results have painted an unexpected picture of the Saturnian system as a very complex and dynamic system.

Perhaps one of the most intriguing results was that the large moon, Titan appeared to be having a much smaller impact on the Saturnian system despite it being extremely large (the 2nd largest in the solar system and large than the planet Mercury) with an unprotected atmosphere that is denser than the Earth’s. Cassini observations revealed that Saturn’s magnetosphere material is dominated by cryogenic plumes from the much smaller icy moon Enceladus. Although the Enceladus plumes are somewhat variable, on average, this moon provides ~285 kg/s of water vapor to Saturn’s magnetosphere (Smith et al. 2021) while Titan’s atmosphere likely only provides <40 kg/s of N2 & CH4 (Johnson et al. 2009).

Thus, the magnetosphere is dominated by water gas from Enceladus rather than nitrogen and hydrocarbons from Titan’s atmosphere. These particles are ejected into the magnetosphere as neutral charged atoms & molecules but unfortunately, such particles are generally much more difficult to detect (with the exception of certain species with specific spectral qualities. Fortunately, charged particles are generally much easier to detect at lower densities. Thus, charged particle observations of ion produced by ionizations of the source neutral particles are used as a proxy for the observing neutral particles. Throughout most of Saturn’s magnetosphere, water-group ions (H3O+, H2O+, OH+ & O+, also referred to as “W+” collectively) originating from the Enceladus plumes’ water vapor generally account for up to 90% of all ions (Thomsen et al. 2010) with hydrogen accounting for the next largest population followed by nitrogen ions presumably from Titan and Enceladus (Smith et al. 2007). Carbon ions exist as a very minor species Saturn’s magnetosphere with global relative abundances remaining pretty steady at ~1% relative to W+. These ions likely originate from the Enceladus plumes as well as hydrocarbons from Titan’s atmosphere. This, abundances and locations of minor/trace species in Saturn’s magnetosphere provide significant insight into source composition and activity.

Tidal forces cause Enceladus plume source rate to vary on the its orbital timescale which is much shorter than particle interactions rates. Thus, the amount of global magnetospheric neutral water particles remains relatively stable over time as shown using UV observations of total oxygen content (Melin et al. 2009). This allows for a stable comparison to examine the spatial and temporal distribution of minor/trace species to provide unique insight into composition and activity of sources of these particles. More specifically, we examine the relative abundances of significant trace species to water-group particles to explore unusual magnetospheric activity. The observations were collected by the CHarge Energy Mass Spectrometer (CHEMS) of the Cassini Magnetosphere Imaging Instrument (MIMI) (Krimigis et al. 2004) which measures mass and mass/charge of ~3-220 keV ions. We conducted a detailed analysis of the relative abundance of C+ to W+ over the entire 13-year mission (2004-2017) and surprising discovered an abrupt feature in the data. The relative abundance of C+ remains fairly constant at ~1% until early in 2014. At this point the relative abundance of C+ rather abruptly increases by half an order of magnitude (to ~5%) and then appears to exponentially fall off and has almost completely recovered by the end of the mission.

In this presentation, we show that this global magnetospheric ion composition modification was observed resulting from an abrupt increase in Titan atmospheric loss most likely from a collisional event, surface activity, solar wind exposure or a interruption in the methane precipitation cycle. Titan was not thought to exhibit such enhanced atmospheric loss but this evidence indicates that such activity can impact the entire magnetosphere and opens up the possibility for similar additional atmospheric loss events on Titan as well as on other bodies.

How to cite: smith, H. T., Robert, R., and Johnson, : An unexpected and intense period of Titan atmospheric loss , EPSC-DPS Joint Meeting 2025, Helsinki, Finland, 7–13 Sep 2025, EPSC-DPS2025-338, https://doi.org/10.5194/epsc-dps2025-338, 2025.

The atmosphere of Titan is a unique natural laboratory for the study of atmospheric evolution and photochemistry akin to that of the primitive Earth (1), with a wide array of complex molecules discovered through infrared and sub-mm spectroscopy (2)(3). A recent work by our team (4) has shed light on Titan’s visible High-Resolution Spectrum - a poorly explored part of Titan’s spectrum, which may nonetheless contain relevant absorption features that could enable a more complete understanding of this moon’s rich atmospheric chemistry (4). On these archived high-resolution VLT-UVES spectra (R < 100 000), it was possible to identify tens of previously unidentified CH4 visible high-resolution features and obtain the first tentative detection of C3 on Titan through its 405 nm “comet”-band.

Despite these encouraging results, further observations covering the entirety of Titan’s visible spectrum at a higher spectral resolution were still required to obtain more conclusive answers regarding the presence of C3 in Titan’s atmosphere, and in order to complete the search for previously uncharacterized CH4 absorption features across the entirety of the visible spectrum (for which dedicated HR linelists are still currently unavailable (5)). We performed these observations with VLT-ESPRESSO at its Ultra High-Resolution (R = 190 000) mode in December 2024 and we present their results here for the first time, as the observations of Titan with the highest spectral resolution conducted so far.

This unprecedented spectral resolution at a considerably high signal-to-noise ratio (SNR > 300) allows for a complete survey of non-solar absorption features on Titan’s visible spectrum, enabling the extraction of a more comprehensive methane visible High-Resolution linelist, from 400 to 780 nm. Using our original Doppler-based line detection method (4) for backscattered planetary atmosphere spectra, we retrieve an updated empirical, low Temperature (T < 200K), ultra high resolution (R = 190.000) line list of methane absorption on Titan, from 400 nm to 780 nm, for which no similar theoretical line lists are yet available (5) and significantly complementing our previous work which was limited to the 520 nm to 620nm range (4). On this new work we identify and characterise hundreds of new high energy CH4 lines, retrieving a number of new CH4 absorption features one order of magnitude higher than the empirical linelist obtained by VLT-UVES presented in our previous work (4). Interestingly, these newly detected individual absorption lines explain previous low-resolution and low-temperature (T < 200K) profiles of visible methane absorption bands (6).

Beyond the CH4 visible band, VLT-ESPRESSO observations' increased spectral resolution and spectral coverage enable the search for other minor chemical compounds on Titan’s atmosphere – namely C3, for which 2 updated linelists have recently been published (7)(8). Here we present the application to this new dataset of Titan’s visible spectrum at an unprecedented spectral resolution this more recent and complete C3 linelist, which, following a preliminary analysis, appears to point to a more study detection of C3 compared to (4). This is since 7 matching features to C3 lines are found in this analysis, with a line depth consistent with the presence of C3 at the upper atmosphere of Titan, with a column density of 1013 cm−2. We also present the search for C2 spectral features on this high-resolution visible spectrum of Titan (9).

This study of Titan's atmosphere with ultra-high-resolution visible spectroscopy presents a unique opportunity to observe a planetary target with a CH4-rich atmosphere, from which CH4 optical proprieties can be studied (10). It also showcases the use of a close planetary target to test new methods for chemical retrieval of minor atmospheric compounds, in preparation for upcoming studies of cold terrestrial exoplanet atmospheres (11).

Figure 1: Line detection with the Doppler Method for Spectral line identification at a section of the 6200 Å CH4 band. Here we compare one nightly VLT-UVES spectra of Titan (in red), with the new VLT-ESPRESSO spectrum of Titan (in blue) and the Kurucz solar spectrum (in black). The many non-solar spectral line on both Titan spectra, originating from a visible CH4, absorption band, illustrate the increased detectability of fainter spectral features in the higher-resolution VLT-ESPRESSO spectrum.

References: (1) Hörst S., 2017; J. Geophys. Res. Planets, doi:10.1002/2016JE005240; (2) Nixon C., et al, 2020; The Astronomical Journal, doi:10.3847/1538-603881/abb679; (3) Lombardo N., et al, 2019, The Astrophysical Journal Letters, 2019 doi:10.3847/2041658213/ab3860; (4) Rianço-Silva R., et al, 2024, Planetary and Space Sciences, 240, 105836, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pss.2023.105836. (5) Hargreaves R., et al, 2020; The Astrophysical Journal Supplement Series, doi:10.3847/1538-4365/ab7a1a; (6) Smith, W.H., et al., 1990, Icarus, 85; (7) Fan, H., et al, 2024, A&A, 681, A6 https://doi.org/10.1051/0004-6361/202243910; (8) Lynas-Gray, A., et al, 2024, MNRAS, 535, https://doi.org/10.1093/mnras/stae2425; (9); Yurchenko, S., et al, 2018, MNRAS, 480, doi:10.1093/mnras/sty2050; (10) Thompson M., et al, 2022; PNAS, doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2117933119; (11) Tinetti G., et al, 2018; Experimental Astronomy, doi:10.1007/s10686-018-9598-x

How to cite: Rianço-Silva, R., Machado, P., Tinetti, G., Martins, Z., Rannou, P., Loison, J.-C., Dobrijevic, M., Dias, J., and Ribeiro, J.: The atmosphere of Titan as seen by VLT-ESPRESSO: the first search for minor compounds with Ultra High-Resolution visible spectra on Titan’s atmosphere, EPSC-DPS Joint Meeting 2025, Helsinki, Finland, 7–13 Sep 2025, EPSC-DPS2025-341, https://doi.org/10.5194/epsc-dps2025-341, 2025.

Motivation. The atmosphere of Titan is a key environment for studying complex organic chemistry in a cold, oxygen-poor and nitrogen-rich environment. Photochemistry of CH4 triggers a rich chemistry, leading to the detection of several organic molecules, including benzene [1]. In addition, Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons (PAH) molecules have been invoked to explain the signal leftover from the non-LTE modelling of CH4 in VIMS limb data [2]. Nevertheless, questions remain about PAH formation and evolution on Titan.

Methodology. In this work, we reanalyse Cassini VIMS limb spectra using a new extended version of the NASA Ames PAH IR Spectroscopic Database [3], containing more than 3000 PAH molecules, with sizes up to 169 rings. We model the PAH emission mechanism, considering the solar irradiance spectrum at the date of the observations and extending the photo-absorption cross-section down to the near infrared. A Non-Negative Least Square (NNLS) fitting is used to obtain information on average PAH size that best fits the VIMS data at 1000, 950 and 900 km and uncertainty on this value is evaluated using a Monte Carlo technique. We included both neutral and anions PAHs. We follow up with Non-Negative Least Chi-square minimisation [4] fitting to gain insight on the type of single PAHs that could reproduce the VIMS residual features.

Results. Preliminary results show that, even considering a larger database of PAHs with different sizes, the average number of aromatic rings of the best-fitting PAHs is only slightly higher than the 10-11 rings found in the earlier study [1]. Also, surprisingly, the largest PAHs are found at higher altitude, up to 1000 km, which is counterintuitive given that PAHs are believed to be the seeds for aerosols formation and their size should increase as the altitude decreases. This could be explained if new formation routes, for example ion-molecule reactions, currently not included in the models, are available at these altitudes. Averaging data over different dates and geolocations could also have an effect. When looking at which single PAH molecule best fit the data, we find the asymmetric, catacondensed PAHs are preferred. These findings challenge existing models of PAH growth and survival in Titan’s atmosphere and call for new modelling efforts.

References:

[1] Coustenis A. et al. 2003 Icar 161 383

[2] M. López-Puertas et al 2013 ApJ 770 132

[3] C.W. Bauschlicher Jr. et al 2018 ApJS 234 32

[4] P Désesquelles et al 2009 J. Phys. G: Nucl. Part. Phys. 36 037001

How to cite: Stikkelbroeck, F., Candian, A., and López Puertas, M.: Revisiting PAHs contribution to Titan’s upper atmosphere., EPSC-DPS Joint Meeting 2025, Helsinki, Finland, 7–13 Sep 2025, EPSC-DPS2025-1444, https://doi.org/10.5194/epsc-dps2025-1444, 2025.

Background/Motivation:

Titan’s atmosphere is an organic factory, producing high-order hydrocarbons from the photolysis of methane by solar ultraviolet radiation [Lavvas et al. 2008]. These organics aggregate together to form tholins, which then sediment out of the atmosphere to the surface. Constraining the temporal evolution and distribution of Titan’s aerosols is required to understand the roles of haze production in the Titan system including radiative heating, dynamics, atmospheric chemistry, and surface erosion/dune formation. Studies of Titan’s hazes have demonstrated significant variability in haze abundance over the course of the Cassini mission and beyond [Rannou et al. 2010, West et al. 2018, Nicols-Fleming et al. 2021]. We seek to expand on this work by considering newly analyzed data from the Cassini Visual and Infrared Mapping Spectrometer (VIMS) in combination with state-of-the-art radiative transfer (RT) models.

Here, we present an analysis of all the VIMS solar occultation data over the course of the Cassini mission. These unique data offer the ability to sample fine vertical structure in both gaseous composition and aerosol abundance. Past studies have leveraged the occultation data occurring in the first half of the mission [Bellucci et al. 2009, Hayne et al. 2014, Maltagliati et al. 2015, Rannou et al. 2022]. Now, we double the dataset, including data from the second half of the mission, providing both a longer temporal baseline and greater spatial coverage through which to understand the formation and distribution of Titan’s aerosols. The final profile of derived vertical abundance permits both a study of the spatio-temporal variability in Titan’s aerosols and more accurate atmospheric profiles for RT modelling, which generally assume constant profiles as derived from the Huygens probe. Accurate RT is critical for atmospheric compensation and interpretation of retrieved surface properties.

Methods:

Occultation observations were attempted on 10 different flybys of Titan over the Cassini mission, with 6 flybys offering data on both the ingress and egress of the flyby for a total of 16 datasets. However, of these 16 datasets, one resulted in no data of the Sun, which was like result of bad VIMS pointing while an additional 7 datasets suffered from significant variability because of Cassini’s thrusters being activated during the acquisition resulting in significant drifts in intensity as the Sun moved about the focal plane. As the occultation requires an accurate baseline of the solar flux prior to the event to determine relative transmission, these observations were discarded from the analysis.

Of the remaining 8 datasets, all were analyzed with a similar approach built around the methodology as described in [Maltagliati et al. 2015]. First, a 2D Guassian was fit to each wavelength-dependent image from the occultation and removed to determine the background residuals. For cases where stray light from Titan was present through the non-solar port, a 2D plane was used to fit and remove the background residuals. After, the 2D Gaussian was refit and the total flux summed across the focal plane. Transmission was then determined for each timestep through division by the average solar flux taken from all altitudes greater than 1000 km. As a final correction, a linear polynomial was fit to all transmission data to account for any additional slow variability in source drift over the course of the acquisition.

Preliminary Results:

Figure 1 displays the results of the occultation data reduction. As evident in Figure 1, significant variability in sampling resolution is observed between the datasets. This results from differences in the integration time, image frame size, and distance of Cassini from Titan at the time of acquisition. Resolutions range from 5-40 km on average. All plots have been color coded to correspond to similar altitudes ranging from 50-500 km. Strong absorptions are observed around 2.3- and 3.3-µm from methane, with additional weaker absorptions around 1.2- and 1.4-µm. Also evident in most observations is the strong carbon monoxide (CO) doublet at 4.8-µm. However, this signature appears to be significantly weaker in later observations, suggesting the potential for spatio-temporal variability in CO on Titan. Variability in the spectral slopes in the continuum from 1.0 - 2.2-µm also demonstrate changes in vertical aerosol abundance over the course of the observations. Most notable is decreased transmission on the T103/T116 ingress datasets, corresponding to similar latitudes at ~30°N, at ~150km altitudes. These data suggest a significant increase in aerosol abundance at mid-latitudes later in the Cassini mission and will be used to place constraints on seasonal circulation of Titan’s atmosphere.

Figure 1: Derived spectral transmission files from eight occultation datasets range from the T10 flyby (Jan. 2006) to the T116 flyby (Feb. 2016). The color corresponds to the sampled altitude for each profile. Strong absorptions from CH4 and CO are observable in the spectra. Variability in spectral slopes are indicative at changes to the vertical aerosol abundance between flybys.

How to cite: Corlies, P., Barnes, J., Soderblom, J., MacKenzie, S., and Hedman, M.: Understanding Titan’s Chemical Factory: An Analysis of VIMS Occultation Data, EPSC-DPS Joint Meeting 2025, Helsinki, Finland, 7–13 Sep 2025, EPSC-DPS2025-1144, https://doi.org/10.5194/epsc-dps2025-1144, 2025.

Introduction

Saturn’s largest moon, Titan, has a dense atmosphere comprised mostly of nitrogen and methane. The photolysis and ionization of these major components

leads to complex chemical reactions, which create substantial diversity among Titan’s minor atmospheric constituents. Remote sensing and molecular pectroscopy historically have been a critical tool for detecting trace gases in Titan’s atmosphere and help corroborate predictions of Titan’s atmospheric composition from photochemical models. Following the Voyager and Cassini missions, which provided a wealth of spectroscopic studies of Titan’s atmosphere, ground-based measurements have been useful for detecting elusive trace gases. The Echelon-Cross-Echelle Spectrometer (EXES) is a high-resolution (R ∼ 90, 000) mid-infrared spectrometer that was previously operated aboard NASA’s Stratospheric Observatory For Infrared Astronomy (SOFIA)(1 ). EXES benefited from the high altitude flights during the SOFIA mission to make observations above the bulk of the atmosphere to avoid strong telluric absorption lines that inhibit ground based mid-IR spectrometers such as its sister instrument TEXES.

Here we present EXES observations of Titan which were made in an attempt to detect two trace gases, triacetylene (C6H2) and dicyanoacetylene (C4N2). C6H2 is an important polyyne and is predicted to form readily from the addition of the ethynyl (C2H) radical with diacetylene (C4H2). It remains yet to

be detected, though, and the previous upper limit study was limited by the lower spectral resolution of Voyager’s IRIS (R ∼ 145)(2 ). Delpech et al. 1994 derived an upper-limit of 6 × 10−11 which would be detectable by EXES.

Gas-phase C4N2 formation is primarily completed through C3N addition to HCN or, alternatively, CN addition to HC3N(3 ). The ice-phase C4N2, which is formed through solid-state photochemical reactions on the surface of HC3N ice grains, has been detected in spectra measured by Voyager’s IRIS and CIRS

during the Cassini mission (4, 5 ), yet C4N2 in the gas-phase remains elusive to spectroscopic detections. Again, previous studies of the gas-phase upper limits (3σ = 1.53 × 10−9) were performed using spectra collected by CIRS (R ∼ 1240) which has a resolving power significantly lower than EXES(6 ). The high-resolution of EXES will help improve on the upper limits of both of these species and allow for an updated comparison to photochemical model predictions of their vertical profiles in Titan’s atmosphere.

Observations and Modeling

Mid-infrared observations of Titan were made in June of 2021, using EXES. These observations aim to detect the ν11 out-of-plane bending mode of C6H2 at 621 cm−1 and the perpendicular ν9 stretch of the gasphase C4N2 at 472 cm−1. Figure 1 shows a small portion of the EXES spectrum measured at the 621 cm−1 spectral setting. In this region there are strong emission features from diacetylene (C4H2) and propyne (C3H4) which must be fit before analyzing the C6H2 upper limits. Highlighted in the blue box is the region where the ν11 vibrational mode for C6H2 should be present.

To model the collected spectra, we use the arch-NEMESIS radiative transfer package which is a new Python implementation of the NEMESIS radiative transfer code (7, 8 ). The radiative transfer modeling of the measured spectra occurs in two steps. The initial step is to retrieve the atmospheric profiles of the aerosols and known gases using the archNEMESIS optimal estimation algorithm. For the 621 cm−1 spectral setting, the vertical profiles of C4H2, C3H4, and aerosol continuum are retrieved, however, at the 472 cm−1 region, there are no emission features to fit and just the continuum level is retrieved by adjusting the aerosol profile. For both spectral regions, we use a temperature profile and initial gas profiles defined in Vuitton et al. 2019 photochemical model (3 ). The quality of each retrieval is determined by a goodnessof-fit metric (χ2) which compares the residual of the modeled spectrum to the noise of the measurement. Following the retrieval, we derive the upper limits by building forward models of the spectral regions where the abundance of each target species is iteratively increased and a subsequent χ2 is determined. We then take the difference, Δχ2, between the retrieved and updated forward model χ2 to find where the abundance causes significant deviation from the retrieved spectrum. Step-profiles, which have a cutoff altitude and constant abundance above this cutoff, were used to determine the upper-limits for each species. This method has been applied for many different upper limits studies of gases predicted in Titan’s atmosphere (9, 10 ).

Results

Based on these observations, C6H2 and gas-phase C4N2 remain undetected and therefore, we derive the upper limits to their atmospheric abundance. We improve upon the upper limits of C6H2 and C4N2 by an order of magnitude for both species. Figure 2 shows Δχ2 increase sharply with increased abundance for both C6H2 and C4N2. For C6H2 the 3σ upper limit (Δχ2 = 9) is on the order of 10−11 and for C4N2, 10−10. These new upper limits improve on the previously derived upper limits by an order of magnitude for each target species. More work is still being done to precisely determine the upper limits and compare these values to the current photochemical model predictions of their abundance. The values of the 1σ, 2σ, and 3σ upper limits for each species will be reported in the presentation. The upper limits derived improved upon the previous upper limits by an order of magnitude and we are currently working on comparing these upper limits to photochemical models of Titan’s atmospheric composition to build a better understanding of the chemical pathways in Titan’s atmosphere which will also be discussed in the presentation.

Acknowledgments

The material is based upon work supported by NASA under award number 80GSFC24M0006.

References

1. Richter et al., 2018

2. Delpech et al., 1994

3. Vuitton et al., 2019

4. Samuelson et al, 1997

5. Anderson et al, 2016

6. Jolly et al., 2015

7. Alday et al, 2025

8. Irwin et al., 2008

9. Nixon et al., 2010

10. Teanby et al., 2013

How to cite: McQueen, Z., DeWitt, C., Jolly, A., Alday, J., Teanby, N., Vuitton, V., Lavvas, P., Penn, J., Irwin, P., and Nixon, C.: Using SOFIA’s EXES to improve the upper limits for C6H2 and C4N2 in Titan’s atmosphere, EPSC-DPS Joint Meeting 2025, Helsinki, Finland, 7–13 Sep 2025, EPSC-DPS2025-1950, https://doi.org/10.5194/epsc-dps2025-1950, 2025.

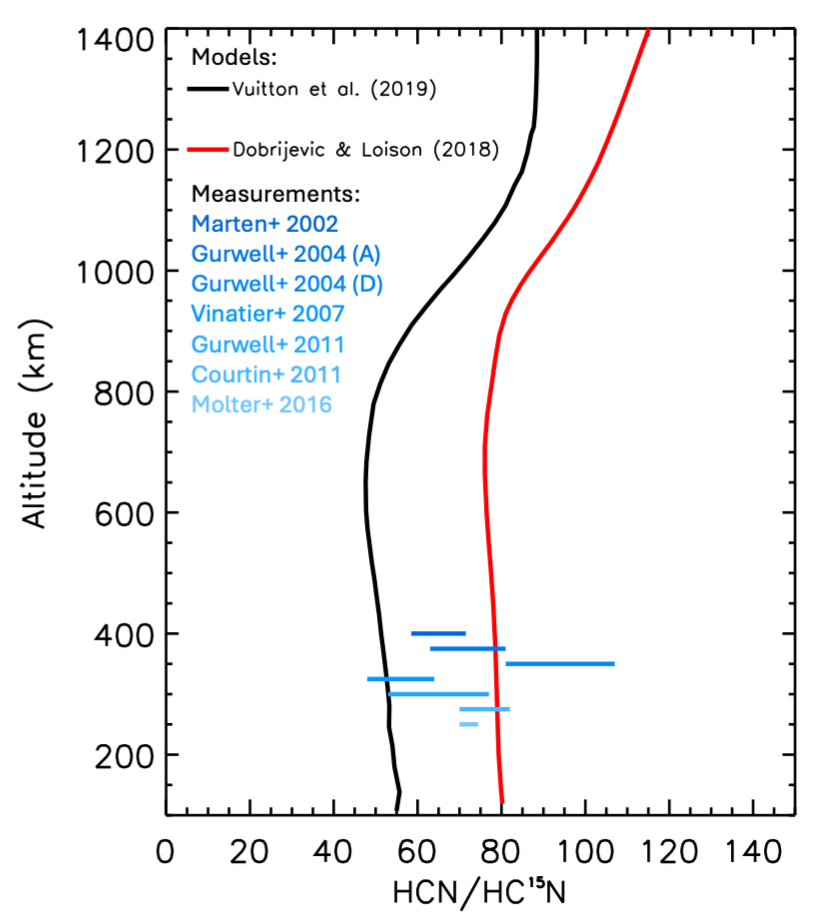

Titan’s substantial atmosphere is primarily composed of molecular nitrogen (N2) and methane (CH4), which are dissociated by solar UV photons and subsequently generate a vast chemical network of trace gases. The composition of Titan’s atmosphere is markedly different than that of Saturn, including both the complex molecular inventory and the hitherto measured isotopic ratios – including that of nitrogen (14N/15N). Atmospheric and interior evolution models (e.g., Mandt et al., 2014) indicate that the atmospheres of Saturn and Titan did not form in the same manner or from the same constituents, and that Titan’s atmospheric N2 may have originated from its interior as NH3. The evolution of 14N/15N in Titan’s atmosphere over time does not result in a value comparable to that measured on Saturn and instead is closer to cometary values; this indicates that the origin of Titan’s atmosphere appears to be from protosolar planetesimals enriched in ammonia and not from the sub-Saturnian nebula. However, selective isotopic fractionation of molecular species in Titan’s atmosphere complicates this picture, as the isotopic ratios may vary as a function of altitude (Figure 1). To further constrain the evolution of Titan’s atmosphere – and indeed, its origin – isotopic ratios must be measured throughout its atmosphere, instead of being interpreted from bulk values likely only representative of the stratosphere.

While the measurement of Titan’s 14N/15N in N2 (167.7; Niemann et al. 2010) places it firmly below the lower limit derived for Saturn (~350; Fletcher et al., 2014), Titan’s atmospheric nitriles (e.g., HCN, HC3N, CH3CN) are further enriched in 15N, resulting in ratios closer to 70 (Molter et al., 2016; Cordiner et al., 2018; Nosowitz et al., 2025). The variation in nitrogen isotopic ratios between the nitriles and N2 is thought to be the result of higher photolytic efficiency of 15N14N compared to N2 in the upper atmosphere (~900 km), resulting in increased 15N incorporated into nitrogen-bearing species (Liang et al., 2007; Dobrijevic & Loison, 2018; Vuitton et al., 2019). As these species are advected to lower altitudes, the nitrogen isotope ratio may vary vertically (Figure 1, red and black profiles), but previous measurements have only presented bulk atmospheric isotope ratios primarily representing Titan’s stratosphere (Figure 1, blue lines).

Recent observations with the Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array (ALMA) have allowed for the derivation of vertical abundance profiles of Titan’s trace atmospheric species and measurements of N, D, and O-bearing isotopologues (Molter et al., 2016; Serigano et al., 2016; Cordiner et al., 2018; Thelen et al., 2019; Nosowitz et al., 2025). However, vertical isotopic ratio profiles have yet to be derived. Here, we utilize observations acquired with ALMA in July 2022 containing high sensitivity measurements of the HC15N J=4–3 transition at 344.2 GHz (~ 0.87 mm) to investigate vertical variations in the 14N/15N of Titan’s HCN. We compare the results of the vertical 14N/15N profile to those predicted by photochemical models to determine the impact of the isotopic-selective photodissociation of nitrogen-bearing molecular species in Titan’s atmosphere, and the impact of the Saturnian and space environments that vary between model implementations.

Figure 1. 14N/15N profile for HCN predicted by photochemical models from Vuitton et al. (2019; black line) and Dobrijevic & Loison (2018; red line). Blue colored bars in the lower atmosphere represent previous HCN nitrogen isotope ratios from Cassini, Herschel, and ground-based (sub)millimeter observations (see Molter et al., 2016, and references therein). Measurements are offset vertically for clarity, and all refer to HC14N/HC15N measurements for the bulk stratosphere.

References:

Cordiner et al., 2018, The Astrophysical Journal Letters, 859, L15.

Dobrijevic & Loison, 2018, Icarus, 307, 371.

Fletcher et al., 2014, Icarus, 238, 170.

Liang et al., 2007, The Astrophysical Journal Letters, 644, L115.

Mandt et al. 2014, The Astrophysical Journal Letters, 788, L24.

Molter et al., 2016, The Astronomical Journal, 152, 42.

Niemann et al., 2010, Journal of Geophysical Research, 115, E12006.

Nosowitz et al., 2025, The Planetary Science Journal, 6, 107.

Serigano et al., 2016, The Astrophysical Journal Letters, 821, L8.

Thelen et al., 2019, The Astronomical Journal, 157, 219.

Vuitton et al., 2019, Icarus, 324, 120.

How to cite: Thelen, A., de Kleer, K., Teanby, N., Hofmann, A., Cordiner, M., Nixon, C., Nosowitz, J., and Irwin, P.: Investigating the Vertical Variability of Titan’s 14N/15N in HCN, EPSC-DPS Joint Meeting 2025, Helsinki, Finland, 7–13 Sep 2025, EPSC-DPS2025-1211, https://doi.org/10.5194/epsc-dps2025-1211, 2025.

Titan is the only solar system satellite that possesses a significant atmosphere, which is composed mainly of N2 and CH4. Within Titan’s upper atmosphere, solar UV photolysis of N2 and CH4 initiates the production of hydrocarbons and nitriles, and the photochemical growth terminates with the formation of a thick organic haze (Waite et al., 2005). These products descend to Titan’s surface and lakes, possibly engaging on prebiotic chemistry with materials from these environments (Raulin et al., 2012). The distributions of N2 and CH4 in Titan’s upper atmosphere, where photochemistry and haze formation are initiated, are highly variable for reasons that are poorly understood. In particular, the Cassini Ultraviolet Imaging Spectrograph (UVIS) and Ion Neutral Mass Spectrometer (INMS) probed densities and temperatures in Titan’s thermosphere (Esposito et al., 2004; Waite et al., 2004). N2 and CH4 densities within Titan’s thermosphere were retrieved from UV solar occultations (Capalbo et al., 2013, 2015), UV stellar occultations (Koskinen et al., 2011; Kammer et al., 2013; Yelle et al., 2021), UV dayglow (Stevens et al., 2015), and INMS in-situ observations (Yelle et al., 2006; Cui et al., 2009; Snowden et al., 2013). During Cassini’s Titan observations, the N2 and CH4 densities both varied by about one order of magnitude. The density profiles do not appear to exhibit strong correlations with geophysical variables such as latitude, longitude, solar zenith angle, and local solar time (Müller-Wodarg & Koskinen, 2025). UVIS scans of Titan’s airglow between 2004 and 2017 provide a global view of the atmosphere, which can help to uncover the origin of the variations. However, most of the 635 UVIS scans were previously unanalyzed. Having analyzed multiple UVIS scans, we present results based on our investigation of variability in Titan’s upper atmosphere.

We implement a fast, simplified optimal estimator to retrieve N2, CH4, and H densities from UVIS scans of Titan’s far ultraviolet (FUV) dayglow (Lavvas & Koskinen, 2022). Our approach’s validity depends on the assumption that solar-driven processes dominate Titan’s dayglow emissions, which we previously demonstrated (Hoover et al., 2024). To characterize variations in temperature and vertical mixing across latitude and time, we construct a Titan atmospheric structure emulator. We create a parametrized pressure-temperature (P-T) profile in the mesosphere and thermosphere. For the lower atmosphere, we incorporate the SVRS temperature profile (Lombardo & Lora, 2023). The SVRS dataset is strongly anchored in Cassini Composite Infrared Spectrometer observations of Titan’s lower atmosphere and simulations of Titan’s stratospheric dynamics. We set the CH4 volume mixing ratio at the stratopause (0.0146063) and use a parametrized Kzz profile (Yelle et al., 2008) to model the CH4 mixing ratio profile throughout the atmosphere. Our fit parameters are the mean temperature in the upper atmosphere (P < 3.9 ∗ 10−10 bar), mesopause temperature, Kzz value in the upper atmosphere, and a scale factor needed to match the H density profile from a photochemical model with the observations. We use emcee (Foreman-Mackey et al., 2013) to retrieve atmospheric structure parameters by fitting the emulator model to the retrieved density profiles.

Based on these algorithms, we present N2, CH4, and H density profiles, as well as atmospheric structure parameters, retrieved from our dataset of UVIS scans. Near the equator, the mean upper atmospheric temperature varies significantly over timescales below one year. For some observations, we perform retrievals at multiple latitudes; in most of these cases, Titan’s mean upper atmospheric temperatures exhibit little change over latitude. Changes in mean upper atmospheric temperature do not appear to be correlated with solar activity, suggesting that other factors, such as activity from Titan’s lower atmosphere or Saturn’s magnetosphere, may influence variations in Titan’s upper atmosphere more significantly. To test the hypothesis that variability in Titan’s upper atmosphere is driven by waves and circulation patterns from the stratosphere (the "intrinsic variability" hypothesis), we compare our retrieved densities and temperatures with output from a Titan Thermosphere General Circulation Model (Müller-Wodarg et al., 2008; Müller-Wodarg & Koskinen, 2025). Upper atmospheric Kzz values derived from our CH4 profiles are more than one order of magnitude higher than those derived from Ar profiles measured by INMS (Yelle et al., 2008), indicating that CH4 is undergoing significant escape.

References:

- Capalbo, F. J., Bénilan, Y., Yelle, R. V., & Koskinen, T. T. 2015, ApJ, 814, 86, doi: http://doi.org/10.1088/0004-637X/814/2/8610.1088/0004-637X/814/2/86

- Capalbo, F. J., Bénilan, Y., Yelle, R. V., et al. 2013, ApJL, 766, L16, doi: http://doi.org/10.1088/2041-8205/766/2/L1610.1088/2041-8205/766/2/L16

- Cui, J., Yelle, R. V., Vuitton, V., et al. 2009, Icarus, 200, 581, doi: http://doi.org/10.1016/j.icarus.2008.12.00510.1016/j.icarus.2008.12.005

- Esposito, L. W., Barth, C. A., Colwell, J. E., et al. 2004, SSR, 115, 299, doi: http://doi.org/10.1007/s11214-004-1455-810.1007/s11214-004-1455-8

- Foreman-Mackey, D., Hogg, D. W., Lang, D., & Goodman, J. 2013, PASP, 125, 306, doi: http://doi.org/10.1086/67006710.1086/670067

- Hoover, D., Koskinen, T., Lavvas, P., & Le Guennic, N. 2024, in AAS/Division for Planetary Sciences Meeting Abstracts, Vol. 56, AAS/Division for Planetary Sciences Meeting Abstracts, 408.04

- Kammer, J. A., Shemansky, D. E., Zhang, X., & Yung, Y. L. 2013, PSS, 88, 86, doi: http://doi.org/10.1016/j.pss.2013.08.00310.1016/j.pss.2013.08.003

- Koskinen, T. T., Yelle, R. V., Snowden, D. S., et al. 2011, Icarus, 216, 507, doi: http://doi.org/10.1016/j.icarus.2011.09.02210.1016/j.icarus.2011.09.022

- Lavvas, P., & Koskinen, T. 2022, in EPSC, EPSC2022–447, doi: http://doi.org/10.5194/epsc2022-44710.5194/epsc2022-447

- Lombardo, N. A., & Lora, J. M. 2023, Icarus, 390, 115291, doi: http://doi.org/10.1016/j.icarus.2022.11529110.1016/j.icarus.2022.115291

- Müller-Wodarg, I. C. F., & Koskinen, T. T. 2025, Chapter 6 - Titan’s neutral upper atmosphere and ionosphere (Titan After Cassini-Huygens, COSPAR Series), 121–156

- Müller-Wodarg, I. C. F., Yelle, R. V., Cui, J., & Waite, J. H. 2008, JGR (Planets), 113, E10005, doi: http://doi.org/10.1029/2007JE00303310.1029/2007JE003033

- Raulin, F., Brasse, C., Poch, O., & Coll, P. 2012, CSR

- Snowden, D., Yelle, R. V., Cui, J., et al. 2013, Icarus, 226, 552, doi: http://doi.org/10.1016/j.icarus.2013.06.00610.1016/j.icarus.2013.06.006

- Stevens, M. H., Evans, J. S., Lumpe, J., et al. 2015, Icarus, 247, 301, doi: http://doi.org/10.1016/j.icarus.2014.10.00810.1016/j.icarus.2014.10.008

- Waite, J. H., Lewis, W. S., Kasprzak, W. T., et al. 2004, SSR, 114, 113, doi: http://doi.org/10.1007/s11214-004-1408-210.1007/s11214-004-1408-2

- Waite, J. H., Niemann, H., Yelle, R. V., et al. 2005, Science, 308, 982, doi: http://doi.org/10.1126/science.111065210.1126/science.1110652

- Yelle, R. V., Borggren, N., de la Haye, V., et al. 2006, Icarus, 182, 567, doi: http://doi.org/10.1016/j.icarus.2005.10.02910.1016/j.icarus.2005.10.029

- Yelle, R. V., Cui, J., & Müller-Wodarg, I. C. F. 2008, JGR (Planets), 113, E10003, doi: http://doi.org/10.1029/2007JE00303110.1029/2007JE003031

- Yelle, R. V., Koskinen, T. T., & Palmer, M. Y. 2021, Icarus, 368, 114587, doi: http://doi.org/10.1016/j.icarus.2021.11458710.1016/j.icarus.2021.114587

How to cite: Hoover, D., Koskinen, T., Lavvas, P., and Le Guennic, N.: Titan’s Upper Atmospheric Structure from Cassini/UVIS Observations, EPSC-DPS Joint Meeting 2025, Helsinki, Finland, 7–13 Sep 2025, EPSC-DPS2025-133, https://doi.org/10.5194/epsc-dps2025-133, 2025.

Please decide on your access

Please use the buttons below to download the supplementary material or to visit the external website where the presentation is linked. Regarding the external link, please note that Copernicus Meetings cannot accept any liability for the content and the website you will visit.

Forward to presentation link

You are going to open an external link to the presentation as indicated by the authors. Copernicus Meetings cannot accept any liability for the content and the website you will visit.

We are sorry, but presentations are only available for users who registered for the conference. Thank you.