- 1Bay Area Environmental Research Institute, CA, United States of America (jovanovic@baeri.org)

- 2NASA Ames Research Center, CA, United States of America

- 3ETH Zürich, Zürich, Switzerland

- 4California Institute of Technology, CA, United States of America

- 5Jet Propulsion Laboratory, California Institute of Technology, CA, United States of America

The identity of the coloring agent, or chromophore, in Jupiter’s atmosphere that causes the planet’s striking red clouds and storms is an area of active research. Despite being studied for more than 50 years across multiple observational missions, including the Pioneer and Voyager flybys, Galileo and Cassini missions, Hubble Space Telescope (HST) observations, and recent data from the Juno spacecraft and the James Webb Space Telescope, the precise mechanisms behind the origins of Jupiter’s red color remain unknown (e.g., West et al., 2004, Sánchez-Lavega et al., 2024). Simon-Miller et al. (2001) using HST images of Jupiter identified three components contributing to Jupiter’s brightness variations. They found that gray spectral brightness variations accounted for ~91% of variation within the images, a strongly blue-absorbing chromophore was responsible for ~8% of variation in or around the tropospheric cloud deck, and a second blue/green coloring agent was necessary to explain the remaining ~1% of variation in upper tropospheric clouds or hazes, including the Great Red Spot (GRS), an anticyclonic storm located 22° south of the planet’s equator.

Various hypotheses have been proposed regarding the chemical composition of the coloring agents or chromophores responsible for the red color of Jupiter’s atmosphere. These chromophores can be divided into three main hypothesized categories:

- Compounds resulting from sulfur chemistry (e.g., Lewis and Prinn, 1970, Sill, 1976, Loeffler et al., 2016, Loeffler and Hudson, 2018);

- Compounds resulting from phosphorus chemistry (e.g., Prinn and Lewis, 1975, Prinn and Owen, 1976, Noy et al., 1981);

- Organic compounds resulting from methane and ammonia photochemistry (e.g., Ferris and Ishikawa, 1988, Carlson et al., 2016).

Different studies have shown that the most promising chromophore analog for fitting spectra of various Jovian atmospheric features, including the GRS and major atmospheric cloud bands such as the Equatorial Zone and Northern Equatorial Belt is the refractory organic material synthesized by Carlson et al. (2016) from the ultraviolet photolysis of a mixture of ammonia and acetylene (Sromovsky et al., 2017, Baines et al., 2019, Braude et al., 2020, Dahl et al., 2021). While the Carlson et al. (2016) chromophore analog shows promise as the likeliest candidate, it remains uncertain due to both a) the complexities and degeneracies with aerosol properties present in radiative transfer models at wavelengths dominated by scattered sunlight, and b) the fact that Carlson et al. (2016) measured the transmission spectrum of the chromophore analog over a limited wavelength range at intermittent times during the sample production and did not determine the chemical composition or the complex refractive index directly over time.

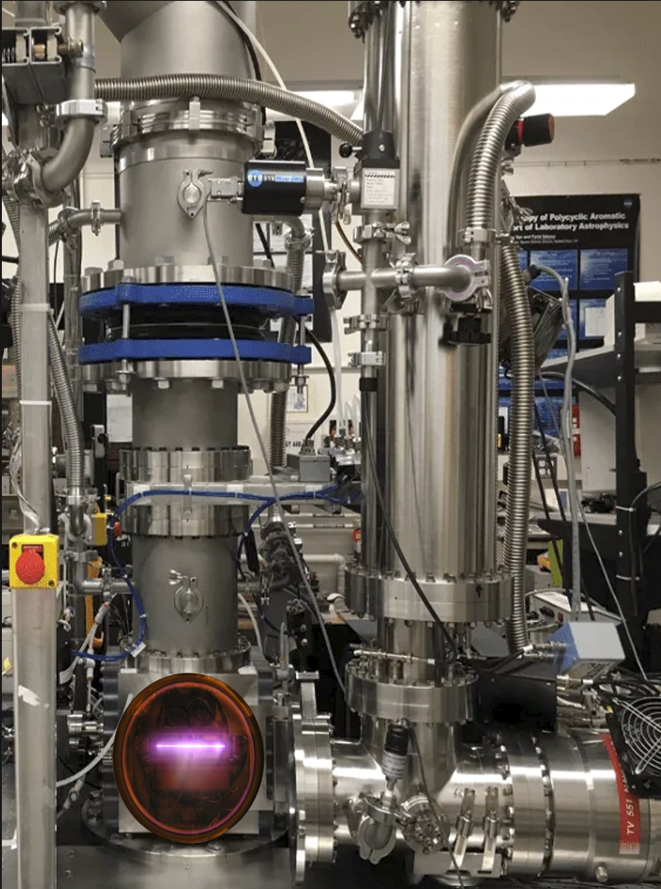

Motivated by the need to understand which gas-phase precursor molecules enables the ultimate formation of solid coloring agents, and to characterize the chemical, physical and morphological properties of these solid chromophores, we therefore propose to build on the work of Carlson et al. (2016) and synthesize new chromophore analogs in the laboratory using the NASA Ames’ COsmic SImulation Chamber (COSmIC, see Figure 1).

Figure 1. NASA Ames’ COSmIC experimental setup.

COSmIC is composed of a vacuum chamber coupled with a pulsed discharge nozzle (PDN). In the PDN, a plasma discharge is generated in the stream of a pulsed supersonic jet-cooled gas expansion (Salama et al., 2017). In the study presented here, we have used COSmIC to produce two different Jupiter chromophore analogs (or Jupiter tholins) from plasma chemistry in Ar:NH3:CH4 (95.5:1:3.5) and Ar:NH3:C2H2 (98:1:1) gas mixtures. In COSmIC, solid particles are produced in the form of grains and carried in the accelerated gas expansion before being jet-deposited onto substrates placed 5 cm downstream of the electrodes. During deposition, the grains stack up and produce a deposit hundreds of nanometers thick.

In this presentation, we will show the morphology and size distribution of the grains that have been analyzed by scanning electron microscopy. We will also present the real and imaginary parts of the complex refractive index (respectively, n and k) of the two Jupiter tholin samples, which have been determined using the Optical Constants Facility (OCF) consisting of a reflectance microscope (0.2-1.7 µm) and a FTIR spectrometer (0.6-200 µm). Additionally, we will present initial radiative transfer model results applying the new chromophore analogs’ optical constants to models of Jupiter’s atmosphere and compare them to models using the Carlson et al. (2016) chromophore.

Acknowledgements: L.J., E.S.O., C.L.R., D.H.W and F.S. acknowledge the NASA SMD PSD ISFM program.

References

West, R. A., et al. (2004) Jupiter: The Planet, Satellites and Magnetospheres, Cambridge Planetary Science, pp. 79-104.

Sánchez-Lavega, A., et al. (2024) Geophysical Research Letters 51:12.

Simon-Miller, A. A., et al. (2001) Icarus 149.1:94-106.

Lewis, J. S. and Prinn, R. G. (1970) Science 169:472-473.

Sill, G. T. (1976) IAU Colloq. 30: Jupiter: Studies of the Interior, Atmosphere, Magnetosphere and Satellites, pp. 372-383.

Loeffler, M. J., et al. (2016) Icarus 271:265-268.

Loeffler, M. J. and Hudson, R. L. (2018) Icarus 302:418-425 .

Prinn, R. G. and Lewis, J. S. (1975) Science 190:4211, pp. 274-276.

Prinn, R. G. and Owen, T. (1976) IAU Colloq. 30: Jupiter: Studies of the Interior, Atmosp here, Magnetosphere and Satellites, pp. 319-371.

Noy, N., et al. (1981) Journal of Geophysical Research:Oceans 86:C12, pp. 11985-11988.

Ferris, J. P. and Ishikawa, Y. (1988) Journal of the American Chemical Society 110:13, pp. 4306-4312.

Carlson, R. W., et al. (2016) Icarus 274:106-115.

Sromovsky, L. A., et al. (2017) Icarus 291:232-244.

Baines, K. H., et al. (2019) Icarus 330:217-229.

Braude, A. S., et al. (2020) Icarus 338:113589.

Dahl, E. K., et al. (2021) The Planetary Science Journal 2.1:16.

Salama, F., et al. (2017) Proceedings of the International Astronomical Union 13.S332:364-369.

How to cite: Jovanovic, L., Sciamma-O'Brien, E., Drant, T., Dahl, E., Braude, A., Ricketts, C., Wooden, D., Baines, K., and Salama, F.: Optical constants of laboratory-generated analogs of the red chromophores in Jupiter’s atmosphere, EPSC-DPS Joint Meeting 2025, Helsinki, Finland, 7–12 Sep 2025, EPSC-DPS2025-1347, https://doi.org/10.5194/epsc-dps2025-1347, 2025.