- 1Charles University, Faculty of Mathematics and Physics, Department of Geophysics, Czechia (kihoulou@karel.troja.mff.cuni.cz)

- 2Nantes Université, Univ Angers, Le Mans Université, CNRS, Laboratoire de Planétologie et Géosciences, LPG UMR 6112, 44000 Nantes, France

Introduction

Together with the ice shell thickness, grain size due to its effect on viscosity is perhaps the most crucial parameter determining the heat transfer regime inside the outer shells of icy moons. Grain growth rates derived from laboratory experiments and terrestrial ice sheets rather differ and strongly depend on the concentration of impurities (1, 2, 3), therefore grain size in the environment of icy moons is still highly uncertain. Most of published models still consider the grain size as a free parameter, yet a few studies have investigated the thermal convection coupled with dynamic recrystallization (4, 5, 6). Here, using the latest description of this process (3), we explore two possible mechanisms for onset of convection. Starting from a conductive temperature profile, we impose either (i) variations of the heat flux coming from the ocean (without any artificial perturbation of the temperature field), or (ii) temperature and melt distribution mimicking an impact (7).

Method

We developed a numerical model of thermal convection in the ice shell with phase transition, melt transport and grain size evolution. In our model, implemented in the finite-element library FEniCS (8), the bottom boundary represents a phase transition between water and ice, and its shape is governed by the flow in the ice shell and by the jump in the heat flux across the ice-water interface. The melt, carried by Lagrangian markers, affects the density and viscosity of the ice, acting as a Rayleigh-Taylor instability (two-phase flow is neglected). The rheology is nonlinear due to the feedback between the stress, the viscosity and the grain size (3, 9), therefore the Stokes problem is solved iteratively. Due to the short time scales of grain size growth and reduction, we evaluate a steady-state value of a grain size in every iteration.

Results

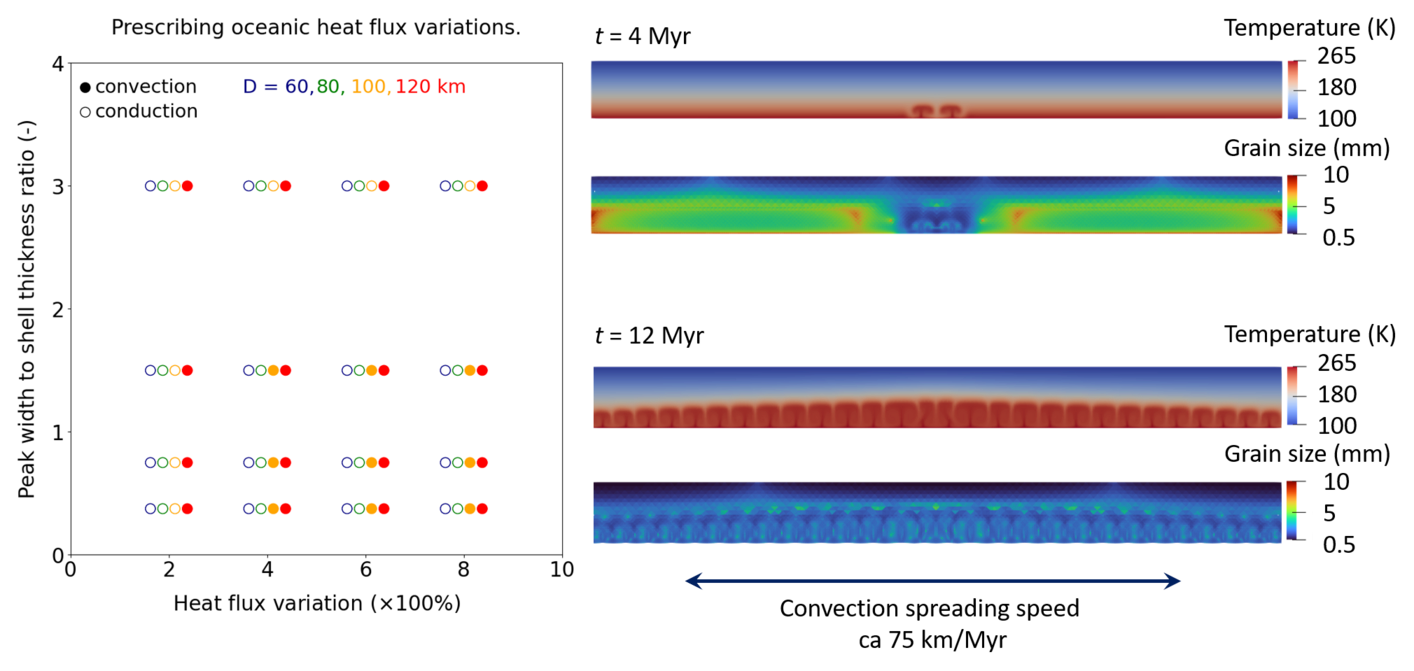

To assess the role of oceanic heat flux in the onset of convection, we performed a parametric study combining the ice shell thickness with the oceanic heat flux anomaly amplitude and width relative to ice shell thickness, see Fig. 1. The ice shell melts above the heat flux peak and depending on the amplitude of the resulting ice-water topography, the stresses might be sufficient to reduce grain size enough to ignite convection. In absence of other mechanisms limiting the grain growth (impurities, tidal stress, global stress due to shell thickening), Fig. 1 shows that convection is triggered only for shells at least 100 km thick and only for rather high heat flux variations (200%). However, once the convection starts, it spreads laterally with speed ca 75 km/Myr. The convective stress keeps the grain size between 1.8 and 3.5 mm, preventing transition back into the conduction regime by grain growth, as similarly reported by ref. (4).

Figure 1. Onset of convection triggered by oceanic heat flux anomaly. Initial shell thickness 100 km, grain growth law from ref. (2) assuming ice with small bubbles. Left: Heat transfer regime diagram for various shell thicknesses and oceanic heat flux anomaly parameters. Right: Shapshots of temperature and grain size.

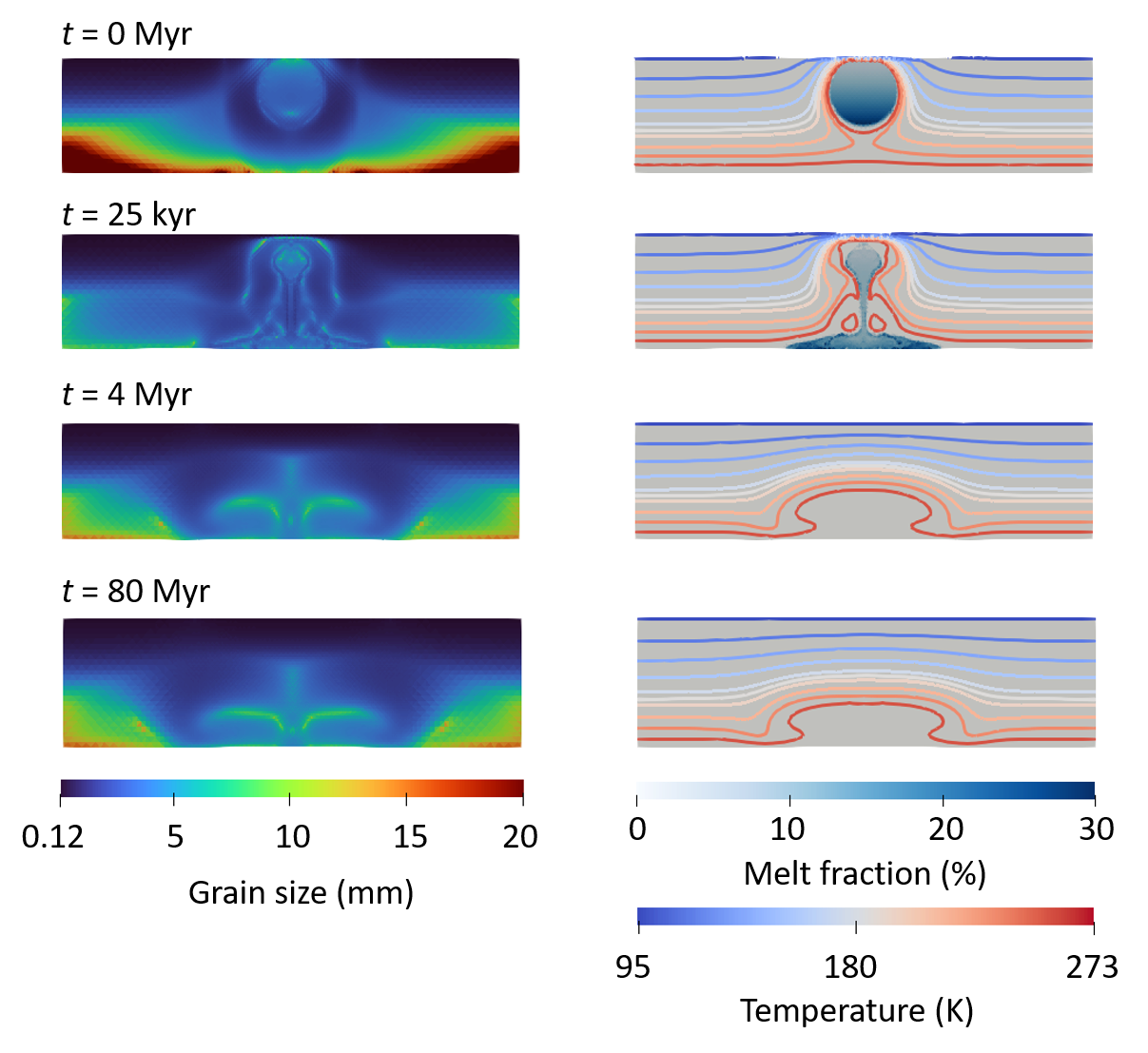

Due to the vastness of parameter space for the impact scenario, we only performed several simulations varying the shell thickness (30 – 100 km) and the impactor radius (6 – 10 km), identifying four possible regimes. First, for a thick ice shell, the convection does not start since the thermal anomaly rapidly vanishes already in the cold lid. Second, with larger thermal anomaly, but with a thin ice shell, only transient convection occurs. Finally, there is a regime in between, with a long-term convection (> tens of Myr) which might either spread (similarly to Fig. 1) or stay localized beneath the impact site (see Fig. 2). In the latter case, the convection is rather sluggish, generating stress large enough to sustain the grain size, yet insufficient to spread laterally.

Figure 2. Impact simulation resulting in an isolated, long-term convection. Initial shell thickness is 50 km, grain growth law from ref. (3) combining laboratory and GRIP data. Left: grain size. Right: temperature (contours) with melt fraction (field).

Conclusions

Oceanic heat flux anomaly can trigger convection only if it is strong (> 200% of average heat flux) and short-wavelength compared to the shell thickness. Such anomalies in the oceanic heat flux are rather unlikely for large moons such as Titan or Ganymede, but might be expected for Enceladus (10). For Enceladus, however, thin ice shell (< 35 km (11)) and lower gravity might be the main limiting factors. Impact heating can trigger convection only if the thermal anomaly reaches the ductile layer and the shell is sufficiently thick. Collapsing melt, if present, provides a further impulse favoring the onset of convection. Our results therefore suggest that global convection in the outer shells of icy moons might be scarcer than previously thought. To investigate the scenarios presented above more thoroughly, we will include pinning effect of impurities (1) and use iSALE 2D (12) to compute realistic post-impact state.

Acknowledgments

This research is supported by Agence Nationale de la Recherche ANR-2020-CE49-0010, Czech Science Foundation project 25-16801S, Charles University project SVV 260825 and CNES through the preparation of the Juice and Europa Clipper missions.

References

1. Durand et al. (2006), JGR: Sol. Ea., 111, F01015.

2. Azuma et al. (2012), JSG, 42, 184–193.

3. Behn et al. (2021), Cryosphere, 15, 4589–4605.

4. Barr and McKinnon (2007), JGR: Planets, 112, E02012.

5. Rozel et al. (2014), JGR: Planets, 119, 416–439.

6. Mitri (2023), Icarus, 403, 115648.

7. Monteux et al. (2014), Icarus, 237, 377–387.

8. Logg et al. (2012), The FEniCS Book, Springer–Verlag

9. Goldsby and Kohlstedt (2001), JGR: Sol. Ea. 106, 11017–11030.

10. Choblet et al. (2017), Nat Astron 1, 841–847.

11. Čadek et al. (2016), GRL, 43, 5653–5660.

12. Gareth et al. (2016), iSALE-Dellen manual, Figshare.

How to cite: Kihoulou, M., Choblet, G., Tobie, G., Kalousová, K., and Čadek, O.: Grain size evolution and heat transfer regime in the shells of icy moons , EPSC-DPS Joint Meeting 2025, Helsinki, Finland, 7–13 Sep 2025, EPSC-DPS2025-1519, https://doi.org/10.5194/epsc-dps2025-1519, 2025.