- 1Atmospheric, Oceanic and Planetary Physics, Department of Physics, University of Oxford, Oxford, UK

- 2Department of Physics, SUPA, University of Aberdeen, Aberdeen, UK

The atmospheric circulation of Jupiter is shaped by a complex interplay between deep internal processes and cloud-level dynamics. Numerical simulations and observational analyses have suggested that Jupiter’s mid-latitude jets are strongly influenced by baroclinic instability [1], which is governed by the planet’s atmospheric thermal structure. Jupiter emits a substantial intrinsic heat flux originating from its interior. Past modelling efforts [2, 3] have demonstrated that this internal energy plays a key role in shaping large-scale atmospheric dynamics.

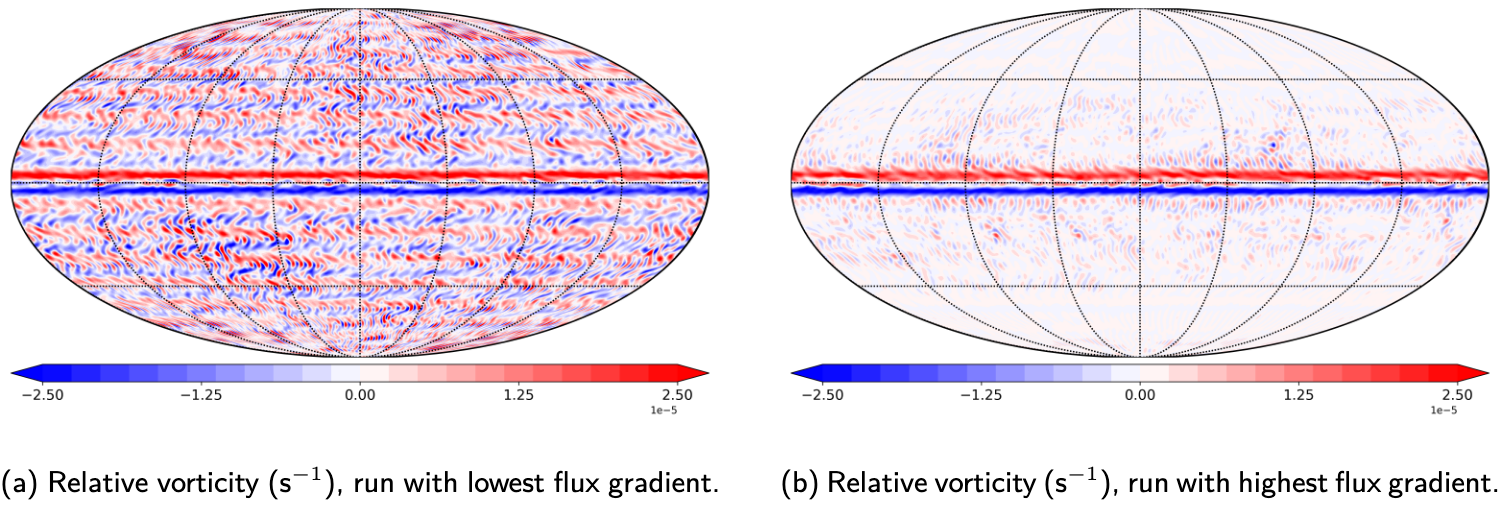

Our previous work [4] showed that latitudinal variations in interior heat flux can significantly impact the structure and behaviour of Jupiter’s mid-latitude jets in a General Circulation Model (GCM). Such an impact is best illustrated by the relative vorticity snapshots from two simulations with the lowest and highest latitudinal flux gradient (see Figure 1). In this study, we present a more detailed analysis linking these jet modifications to changes in the atmospheric thermal structure and, consequently, to the strength and distribution of baroclinic eddy activity. In particular, we use the Lorenz energy cycle framework to diagnose how variations in deep thermal forcing influence baroclinic energy conversion and eddy-mean flow interactions. We further examine the implications for meridional transport and the water cycle within Jupiter’s weather layer.

Additionally, we present a control simulation in which the potential temperature at the model’s lower boundary is forced toward a fixed value (a deep adiabat setup). We compute the equivalent upward heat flux associated with this forcing to place it in the context of previous models that impose constant or latitudinally varying interior heat flux. This allows a direct comparison of how different representations of deep thermal forcing affect upper-atmospheric dynamics.

Finally, we discuss the broader implications of these findings for future weather-layer models of Jupiter and other gas giant planets, especially on the effect of bottom boundary conditions in representing the coupling between deep and observable atmospheric dynamics.

Figure 1: Mollweide projection of the relative vorticity at 1 bar at the end of two simulations.

Reference:

[1] Read, P. L. (2023). The dynamics of Jupiter’s and Saturn’s weather layers: a synthesis after Cassini and Juno. Annual Review of Fluid Mechanics, 56(1), 271–293. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-fluid-121021-040058

[2] Liu, J., & Schneider, T. (2011). Convective Generation of Equatorial Superrotation in Planetary Atmospheres. Journal of the Atmospheric Sciences, 68(11), 2742-2756. https://doi.org/10.1175/JAS-D-10-05013.1

[3] Young, R. M. B., Read, P. L., & Wang, Y. (2018). Simulating Jupiter’s weather layer. Part I: Jet spin-up in a dry atmosphere. Icarus, 326, 225–252. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.icarus.2018.12.005

[4] Hu, X. and Read, P.: Latitudinal Variation in Internal Heat Flux in Jupiter's Atmosphere: Effect on Weather Layer Dynamics, Europlanet Science Congress 2024, EPSC2024-669, https://doi.org/10.5194/epsc2024-669, 2024.

How to cite: Hu, X., Read, P., Young, R., and Colyer, G.: The Role of Bottom Thermal Forcing on Modulating Baroclinic Instability in a Jupiter GCM, EPSC-DPS Joint Meeting 2025, Helsinki, Finland, 7–12 Sep 2025, EPSC-DPS2025-1624, https://doi.org/10.5194/epsc-dps2025-1624, 2025.