- 1School of Chemistry, University of Leeds, Leeds, UK

- 2Institute of Climate and Atmospheric Science, University of Leeds, Leeds, UK

The upper haze region of Venus’ atmosphere (~70-90 km) has been shown to experience cold pockets that may give rise to ice clouds that form from the freezing of sulphuric acid droplets (Turco et al., 1983) On Earth cirrus cloud often form through the hygroscopic growth of aquoue aerosol, but temperatures in Venus’ upper haze region regularly drop well below those of the coldest cirrus clouds on earth (~185 K). However, freezing of sulphuric acid droplets under conditions relevant for Venus’ upper haze region have not been experimentally investigated. Here, we describe our work using new laboratory freezing measurements in combination with the Solar Occultation in the InfraRed SOIR retrievals to better understand the atmospheric conditions around 80 km and determine if these conditions are suitable for the crystallisation of water and CO2 ice.

First, we experimentally explored the homogeneous nucleation of H2O ice in sulphuric acid solutions using a liquid nitrogen-cooled cryo-microscope setup, where droplet emulsions (oil/surfactant mix and H2SO4 solution with droplets of around 10 to 100 µm) are created using a microfluidic device. With this setup, we were able to extend the results from previous studies to lower temperatures and higher sulphuric acid concentrations (Bertram et al., 1996; Koop et al., 1998). We observed crystallisation down to 154 K, but this crystallisation was increasingly restricted by slow crystal nucleation and growth rates at lower temperatures. Crystallisation was not observed below 154 K, consistent with the formation of ultra-viscous or glassy solutions. To further explore the possibility of water ice cloud formation on Venus, we also examined the retrievals of temperature, water vapour mixing ratio and pressure from the Solar Occultation in the InfraRed (SOIR) instrument onboard the Venus Express orbiter (Mahieux et al., 2023). Using this data, we were able to calculate the expected sulphuric acid concentrations using the parameterisation from Tabazadeh et al. (1997), indicating that, in about 30% of the SOIR profiles, H2O ice nucleates homogeneously in liquid aqueous H2SO4 droplets or heterogeneously on glassy aqueous H2SO4 droplets. Using an average particle number density of 0.5 cm-3, which was previously reported by Luginin et al. (2018), we would expect an average size of ~1 µm ice crystals to form in the upper haze layer of Venus.

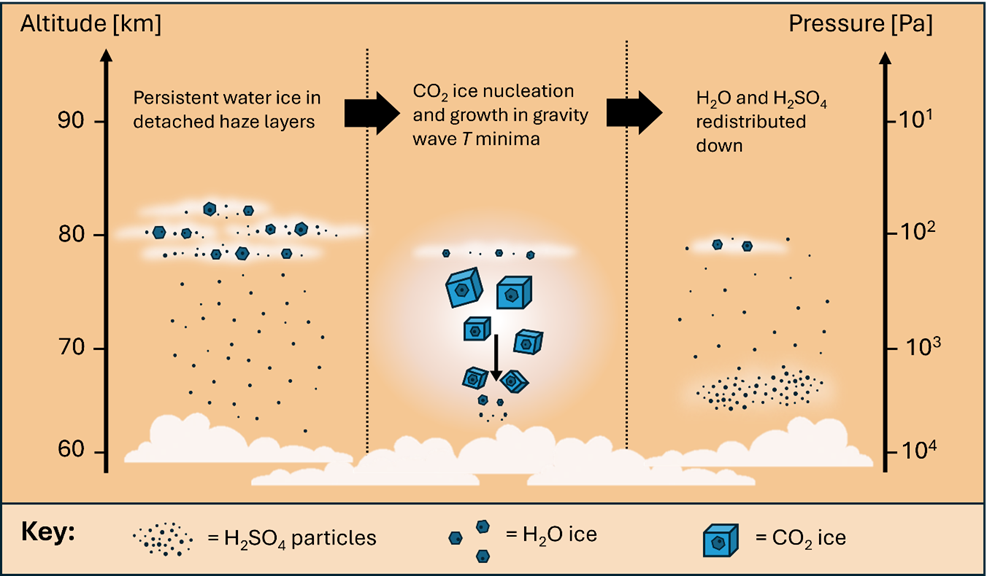

Around 36% of the SOIR profiles reveal that these altitudes experience temperature extremes which low enough (< 140 K) that the atmosphere is stable with respect to crystalline CO2 particles. A 1D model was developed to investigate the influence of gravity waves, the formation of crystalline CO2 and the impact on the upper haze region of the atmosphere. Our 1D model showed that under these conditions, crystals will grow rapidly in the cold phase of a wave to sizes large enough for precipitation downwards to the underlying warm phase where the CO2 sublimates. Therefore, the formation of crystalline CO2 particles creates a mechanism for the redistribution of sulphuric acid particles and water to lower levels in the atmosphere.

Overall, we conclude that cirrus-like water ice clouds likely form and persist in large parts of the upper haze layer on Venus. Due to the variable nature of conditions in this region of the Venusian atmosphere, temperatures will sometimes fall well below 140 K, resulting in the rapid precipitation of CO2 particles. This will likely create a mechanism for the downward transfer of sulphuric acid, water and other materials to the warmer regions of the atmosphere.

Figure 1. The hypothesised mechanism of how temperature variations impact cloud formation and the redistribution of atmospheric constituents. We propose that persistent water ice clouds may be a common feature of the upper haze layer, and these ice crystals may provide the surface on which CO2 ice nucleates in temperature minima driven by gravity waves. The rapid growth and sedimentation of cubic CO2 ice particles would then redistribute H2SO4 particles downwards to the warmer regions of the Venusian atmosphere.

References:

Bertram, A. K., Patterson, D. D., & Sloan, J. J. (1996). Mechanisms and temperatures for the freezing of sulfuric acid aerosols measured by FTIR extinction spectroscopy. The Journal of Physical Chemistry, 100(6), 2376–2383. https://doi.org/10.1021/jp952551v

Koop, T., Ng, H. P., Molina, L. T., & Molina, M. J. (1998). A new optical technique to study aerosol phase transitions: The nucleation of ice from H2SO4 aerosols. The Journal of Physical Chemistry A, 102(45), 8924–8931. https://doi.org/10.1021/jp9828078

Luginin, M., Fedorova, A., Belyaev, D., Montmessin, F., Korablev, O., & Bertaux, J.-L. (2018). Scale heights and detached haze layers in the mesosphere of Venus from SPICAV IR data. Icarus, 311, 87–104. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.icarus.2018.03.018

Mahieux, A., Robert, S., Piccialli, A., Trompet, L., & Vandaele, A. C. (2023). The SOIR/Venus Express species concentration and temperature database: CO2, CO, H2O, HDO, H35Cl, H37Cl, HF individual and mean profiles. Icarus, 405, 115713. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.icarus.2023.115713

Tabazadeh, A., Toon, O. B., Clegg, S. L., & Hamill, P. (1997). A new parameterization of H2SO4/H2O aerosol composition: Atmospheric implications. Geophysical Research Letters, 24(15), 1931–1934. https://doi.org/10.1029/97GL01879

Turco, R. P., Toon, O. B., Whitten, R. C., & Keesee, R. G. (1983). Venus: Mesospheric hazes of ice, dust, and acid aerosols. Icarus, 53(1), 18–25. https://doi.org/10.1016/0019-1035(83)90017-9

How to cite: Alden, K. A., Egan, J. V., James, A. D., Tarn, M. D., Plane, J. M. C., and Murray, B. J.: The Formation of Cirrus-Like Water and Carbon Dioxide Ice Clouds in Venus’ Upper Haze Layer, EPSC-DPS Joint Meeting 2025, Helsinki, Finland, 7–12 Sep 2025, EPSC-DPS2025-1798, https://doi.org/10.5194/epsc-dps2025-1798, 2025.