- 1Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory, (richard.cartwright@jhuapl.edu)

- 2Lowell Observatory

- 3Northern Arizona University

- 4Space Telescope Science Institute

- 5Southwest Research Institute, San Antonio

- 6University of Maryland

- 7NASA Goddard Space Flight Center

- 8University of Idaho

- 9California Institute of Technology

- 10Jet Propulsion Laboratory, California Institute of Technology

- 11Southwest Research Institute, Boulder

- 12Institut de Planétologie et d’Astrophysique

- 13KTH Royal Institute of Technology

Over the past 20+ years, ground-based observations have determined that the surfaces of the large Uranian moons Ariel, Umbriel, Titania, and Oberon are enriched in CO2 ice via the detection of a CO2 “triplet band” between 1.9 and 2.1 µm [1,2]. The spectral properties of the detected CO2 is strikingly similar to crystalline CO2 ice measured in the laboratory. The origin of CO2 on these moons and across the Uranus system, however, remains uncertain. CO2 ice is unstable at the estimated peak surface temperatures of these moons (80-90 K), and it must be replenished [3]. It has been suggested that CO2 could be formed radiolytically via irradiation of H2O ice mixed with carbon-bearing compounds, possibly explaining the stronger CO2 features detected on the trailing hemispheres of these satellites [1,2]. Alternatively, the large moons of Uranus are candidate ocean worlds that may host subsurface saline oceans, possibly enriched in carbonate (CO32-) species and CO2. These carbon-bearing compounds could be outgassed or exposed through geologic processes [4]. Understanding the origin of CO2 and other carbon oxides in the Uranus system is one of the key science questions driving the rationale for future measurements made by a near-infrared (NIR) mapping spectrometer onboard a Uranus orbiter [5].

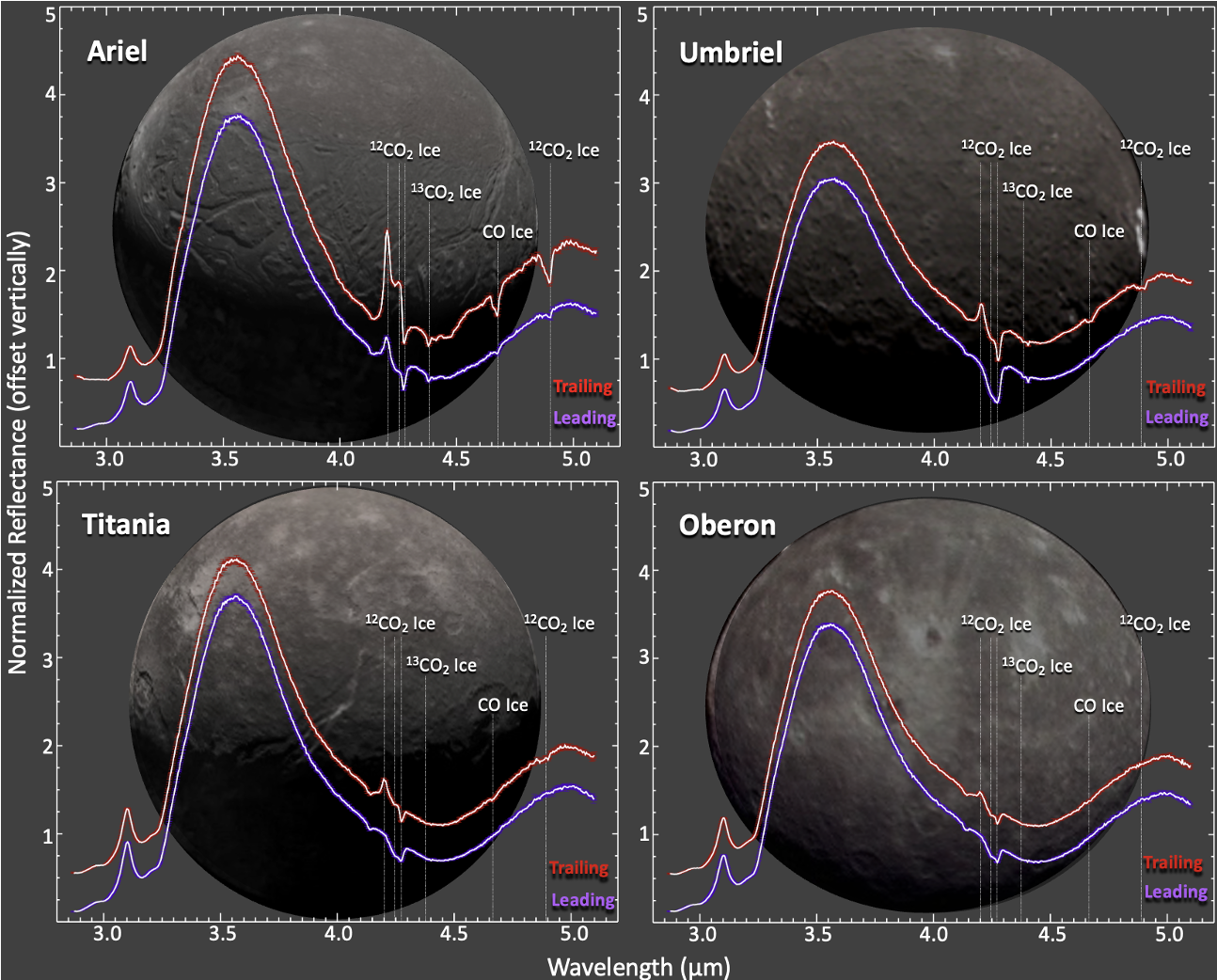

More recent observations made with the NIRSpec spectrograph (G395M, 2.9 – 5.1 µm, R ~ 1000) on the James Webb Space Telescope (program 1786, [4]) were able to identify the strong CO2 asymmetric stretch fundamental mode (ν3), roughly spanning 4.2 to 4.4 µm, a wavelength range inaccessible from the ground due to telluric CO₂ absorption. The CO2 ν3 mode is a factor of ~1000 stronger than the CO2 triplet band measured in prior ground-based observations, and therefore, we predicted that the Uranian moons would exhibit strong and possibly saturated CO2 ice absorption features across the 4.2 to 4.4 µm wavelength range, similar to NIRSpec data of Neptune’s moon Triton [6]. However, the 12CO2 ice bands detected by NIRSpec on the trailing hemispheres of these moons are surprisingly weak, and instead, are convolved with scattering peaks that obscure these absorption features (Figure 1). NIRSpec also revealed 12CO2 on the leading hemispheres of these moons and hyper-volatile CO ice on their trailing sides. Furthermore, 13CO2 is present, primarily on the inner moons Ariel and Umbriel, and CO3-bearing species, carbon chain oxides (CXO2), and CN-bearing organics (nitriles) may also be present on Ariel and Umbriel (Figure 1). Thus, the surfaces of the large Uranian moons are enriched in carbon oxides, especially Ariel [4].

Figure 1: JWST/NIRSpec data (G395M) of the large Uranian moons, normalized to 1 at 4.14 µm and offset vertically for clarity.

At first glance, the detected species and their hemispherical distributions are broadly consistent with prior ground-based observations, supporting radiolytic production of CO2 and other carbon oxides via charged particles trapped in Uranus’ magnetosphere. However, none of the data display notable hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) combination modes near 3.51 µm, features that laboratory experiments have shown to emerge in irradiated H2O ice substrates (< 100 K), in particular when mixed with small amounts of CO2 [7], representing conditions relevant to the surfaces of Uranus’ moons. Furthermore, icy satellites at Jupiter and Saturn tend to display darker and redder trailing hemispheres over UV/VIS wavelengths due to irradiation by corotating plasma, but observations made with Hubble’s Space Telescope Imaging Spectrograph (~200 – 550 nm) indicate no such hemispherical asymmetry in albedo for the large moons of Uranus [8]. Because Uranus’ magnetosphere is notably offset from the orbital plane of its satellites (~59°) and seemingly devoid of heavy ions (i.e., Cn+, On+), it is possible that moon-magnetosphere interactions may be somewhat limited at Uranus. Instead, perhaps CO2 is primarily native to the large moons and exposed by geologic processes, such as cratering, tectonism, cryovolcanism, and outgassing.

Other observations by JWST (program 4645) have revealed that CO2 is present across the Uranian system, including in its rings, ring moons, and irregular satellites [9,10]. The origin(s) of CO2 on these smaller bodies and rings is presumably varied, but almost certainly includes native sources of CO2, especially on the far-flung irregular satellites that orbit well beyond the influence of Uranus’ magnetosphere and exhibit strong 4.27 µm and 2.7 µm features, consistent with native CO2. Similar to the large moons, CO2 ice is unstable on these small bodies and rings and must be replenished and trapped in more refractory compounds.

To gain a more complete understanding of the origin and nature of these species will require a Uranus orbiter equipped with a NIR mapping spectrometer and a charged particle suite making measurements during close passes [11]. We will present NIRSpec results and analyses for carbon oxides on the large moons Ariel, Umbriel, Titania, and Oberon and provide an update on the developing picture of the origin of carbon oxides in the Uranus system in the JWST era.

[1] Grundy, W. et al., 2006. Icarus 184.

[2] Cartwright, R.J. et al., 2022. The Planetary Science Journal, 3, 8.

[3] Sori, M.M. et al., 2017. Icarus, 290, pp.1-13.

[4] Cartwright, R.J. et al., 2024. The Astrophysical Journal Letters, 970, L29.

[5] National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine 2023. Origins, Worlds, and Life:

Planetary Science and Astrobiology in the Next Decade.

[6] Wong, I. et al., 2023. AGU Fall Meeting Abstracts. P44B-08.

[7] Mamo et al. PSJ, submitted.

[8] Cartwright, R.J. et al., 2022. AAS/DPS Meeting 54, abstract 106.01.

[9] Belyakov, M. et al., 2024. AAS/DPS Meeting 56, abstract 405.02.

[10] Belyakov, M. et al., April 2025. Ice Giant Systems Seminar Series.

[11] Cartwright, R.J. et al., 2021. The Planetary Science Journal, 2 (3), p.120.

How to cite: Cartwright, R. J., Grundy, W. M., Holler, B. J., Raut, U., Nordheim, T. A., Neveu, M., Glein, C. R., Hedman, M. M., Belyakov, M., DeColibus, R. A., Villaneuva, G. L., Protopapa, S., Tegler, S. C., Beddingfield, C. B., Quirico, E., Castillo-Rogez, J. C., and Roth, L.: JWST Observes the CO2-rich Surfaces of Uranus’ Large Moons , EPSC-DPS Joint Meeting 2025, Helsinki, Finland, 7–12 Sep 2025, EPSC-DPS2025-182, https://doi.org/10.5194/epsc-dps2025-182, 2025.