- 1Institute of Microwaves and Photonics (LHFT), Friedrich-Alexander- Universität Erlangen-Nürnberg (FAU), 91058 Erlangen, Germany

- 2Microwaves and Radar Institute, German Aerospace Center (DLR), 82234 Weßling, Germany

- 3Department of Human Sciences, Link Campus University, 00165 Rome, Italy

- 4ipartimento di Ingegneria dell’Informazione, Elettronica e Telecomunicazioni (DIET), La Sapienza Università di Roma, 00184 Rome, Italy

- 5Department of Astronomy, Cornell University, Ithaca, NY 14850 USA

- 6French Center for Scientific Research (CNRS), Paris, France

- 7NASA Goddard Space Flight Center (GSFC), Greenbelt, MD USA

1. Introduction

Cassini’s RADAR altimetry data enabled the investigation of suspended particles and nitrogen gas bubbles in Titan’s hydrocarbon lakes and seas. These bodies, composed primarily of methane and ethane with dissolved nitrogen, may contain inclusions such as water ice, organic particles (e.g., tholins, nitriles), and nitrogen gas. Solid particles can originate from atmospheric haze, fluvial erosion, or precipitation, and may accumulate through sedimentation or surface runoff. Nitrogen bubbles are thought to form via supersaturation processes, triggered by temperature changes or increased ethane concentration during rainfall, leading to nitrogen exsolution and bubble formation near the seabed [1-3].

We present a methodology to constrain the size and density of both solid and gaseous inclusions using Cassini RADAR altimetric returns. A physical model based on Mie scattering and radiative transfer theory, compares modeled and observed surface-to-volume power ratios (SVR) to assess the inclusion detectability in Titan's liquid environments [4].

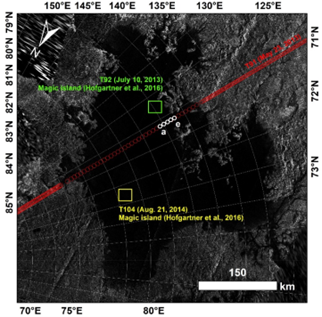

Figure 1. Selected bursts from T91 altimetric observation acquired by the Cassini RADAR.

2. Dataset, modelling and assumptions

We analyze altimetric data from the Cassini RADAR acquired at Ku-band (13.78 GHz, λ = 2.17 cm) acquired during fly-by T91 (Fig. 1). The data were processed using the Cassini Processing of Altimetric Data (CPAD), including incoherent averaging and range compression [5]. To enhance the nominal 35-m resolution, we applied super-resolution (SR) method based via Burg algorithm [6,7], improving surface/subsurface peak separation.

Nadir-looking radar observations in altimetry mode allow for the analysis of suspended inclusions in a homogeneous liquid medium. The received waveform enables surface, subsurface, and volume-scattered power measurement from which constrain inclusion size and density. With the objective of obtaining an expression for the Surface-to-Volume scattering power Ratio (𝑆𝑉𝑅), we model a liquid column containing uniformly distributed spherical particles and evaluate the volume backscattered power based on radiative equilibrium. Reflected and transmitted powers are defined using the surface Fresnel coefficient, dependent on the host dielectric constant, and a two-way transmissivity term. The total volume backscattering cross section includes both this transmissivity and the individual particle backscatter cross sections. Signal attenuation from particle scattering and absorption—mainly influenced by size and loss tangent—is also considered. The model assumes identical dielectric properties, no polarization or multiple scattering effects, and neglects shadowing, valid for particles smaller than the radar wavelength. The final expression, obtained for the case of a beam limited configuration, is

where 𝑃𝑆 and 𝑃𝑉 are the power reflected by the surface interface and through the volume respectively, 𝜎𝑜𝑉 and 𝑘𝑒 are the volume backscattering and extinction coefficients , 𝜃3,𝑑𝐵2 is the antenna beamwith at -3 dB, 𝑧1 and 𝑧2 are the integration depths [4].

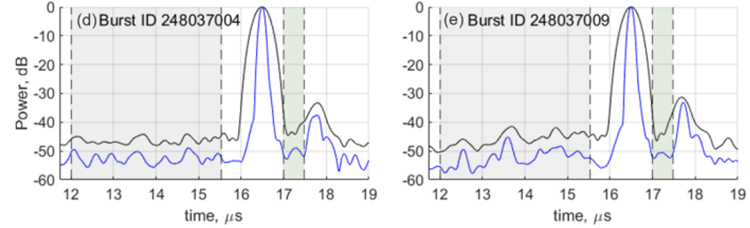

Figure 2. Two of the selected altimetric observations acquired during fly-by T91 over Ligeia Mare, before and after super-resolution processing, in black and blue respectively. The area highlighted in green refers to the integrated waveform, while the gray one to the integrated noise.

3. Methodology and SVR Measurement

SVR was measured using T91 data over Ligeia Mare, where a consistent seabed echo was detected at approximately 160 m depth [5]. To improve seabed detectability, windowing has applied to the waveform, leading to degradation of the range resolution and limiting the available integration window. This required the application of super-resolution techniques to widen the final integration window between the surface and the subsurface, as shown in Fig.2.

The presence of volume scattering has then been evaluated by comparing the measured SVR with the integrated Signal-to-Noise Ratio (SNR𝑖𝑛𝑡). The measured volume power resulted falling between the integrated noise level across all observations, with lesser variation than 2-𝜎, indicating no clear evidence of volume scattering. Therefore, measured SVR served as an upper limit, constraining the possible size and density of inclusions. This upper bound defines a solution space where, for a given density, a maximum particle size is established—and vice versa—based on the modeled relationship between volume scattering and inclusion properties.

4. Results

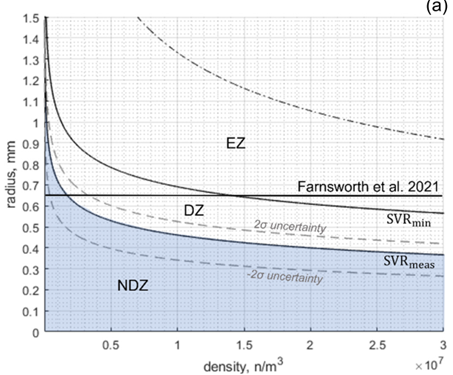

Assumed a host medium composed of a liquid mixture of nitrogen-methane-ethane, with dielectric properties defined by a relative permittivity ε′ₕ = 1.72 and loss tangent tgδ = 3.5×10⁻⁵. Our analysis includes both suspended particles and nitrogen gas bubbles as potential inclusions. In Fig. 3, the measured SVR value of 45.92 dB delineates the boundary between two regimes: Non-Detection (ND) zone, where no volume scattering is observed, the Detection Zone (DZ), where scattering would be detectable by the radar, and an Extinction Zone (EZ), where excessive scattering or absorption would fully attenuate the signal, is also shown. By incorporating particle radius estimates from previous literature, the EZ allows us to define the maximum volume fraction at which inclusions become undetectable due to attenuation. Conversely, the DZ indicates the specific volume density required to match the measured SVR.

Figure 3. The figure shows the SVR derived from T91 Cassini RADAR data, modeled using a methane/ethane/nitrogen liquid host with nitrogen gas bubbles. The blue area represents combinations of particle size and density consistent with the absence of volume scattering. Horizontal lines indicate particle sizes from previous studies, while the black solid lines mark the measured SVR, setting upper limits on bubble density for a given size—or maximum size at varying densities.

For nitrogen-gas bubbles with radius of 0.65 mm from laboratory data, the maximum undetectable volume fraction was estimated at 0.19% [2]. For solid inclusions, the study found that particles smaller than approximately 0.34 mm (water ice), 0.5 mm (nitriles), and 0.84 mm (tholins) remain undetectable without causing extinction of the radar signal. Considering a realistic particle size range of 0.025–1.25 mm, the maximum detectable volume fractions were calculated to be 0.02%–3.49% for water ice, 0.03%–1.43% for nitriles, and 0.16%–1.52% for tholins. These results offer constraints on inclusions properties and inform detectability limits of radar systems, guiding future missions planning to Titan or similar icy moons [4].

References

[1] Barnes et al. 2011

[2] Farnsworth et al., 2019

[3] Cordier and Liger-Belair, 2018

[4] Gambacorta et al., 2024

[5] Mastrogiuseppe et al., 2014

[6] Raguso et al., 2024

[7] Gambacorta et al., 2022

How to cite: Gambacorta, L., Mastrogiuseppe, M., Carmela Raguso, M., Poggiali, V., Cordier, D., and Farnsworth, K. K.: Titan lakes and seas: estimation of nitrogen and solid particleS content via Cassini RADAR data, EPSC-DPS Joint Meeting 2025, Helsinki, Finland, 7–12 Sep 2025, EPSC-DPS2025-1891, https://doi.org/10.5194/epsc-dps2025-1891, 2025.