- German Aerospace Center (DLR), Berlin, Germany / Freie Universität Berlin, Berlin, Germany

The presence of an ocean beneath the Enceladus’ ice shell makes this Saturnian moon a high priority target for future planetary exploration [1]. Water jets that have been observed at the south pole by NASA’s Cassini mission [2] are thought to originate from a global ocean and provide a direct window into the subsurface composition [3]. These jets generate a highly porous material that, due to its low thermal conductivity, affects the thermal state of the ice shell.

The analysis of pit chains on the surface of Enceladus indicates that locally the porous layer can be as thick as 700 m [4]. Such a thick porous layer can locally increase the temperature of the ice shell, leading to a low viscosity. This may promote solid-state convection in regions where the ice shell is covered by such a layer, whereas regions with thin porous layers could be characterized by conductive heat transport. Moreover, due to its effect on the ice shell temperature, the porous layer can strongly attenuate the signal of radar sounders that have been proposed to investigate the Enceladus’ subsurface [5, 6].

Here, we use the geodynamical code GAIA-v2 [7] to investigate the effects of a porous layer on the thermal state and dynamics of Enceladus’ ice shell. GAIA-v2 was originally built to model convection in the rocky mantle of terrestrial planets [8,9,10] but has recently been adapted to investigate large-scale dynamics in the shells of icy moons [11,12]. Our initial simulations use a 2D cylindrical geometry with an 18° arc computational domain, free-slip boundaries, and an Arrhenius rheology with diffusion creep, dislocation creep, as well as basal slip and grain-boundary sliding deformation mechanisms.

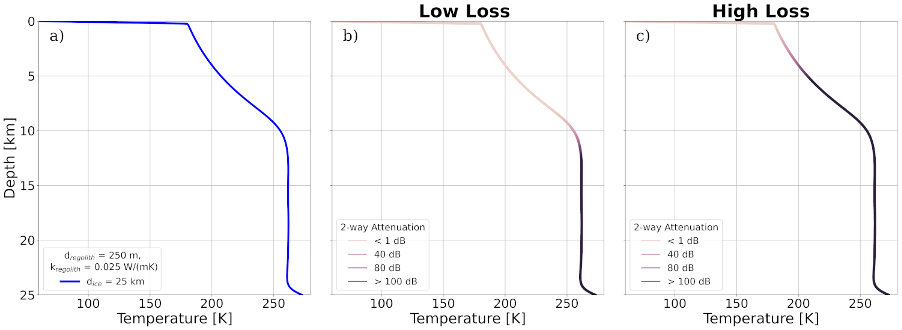

Using the resulting thermal state, we calculate the associated two-way radar attenuation at each location within the ice shell. We test different values of the ice shell thickness (5 – 35 km, [13]), porous layer thickness (d = 0 – 750 m), and its thermal conductivities (k = 0.1 – 0.001 Wm-1K-1 [14,15]). To account for chemical impurities within the ice shell we test a “low” loss scenario that considers a pure water ice shell and a “high” loss case that assumes a homogeneous mixture of water ice and chlorides in concentrations extrapolated from the particle composition of Enceladus’ plume [5].

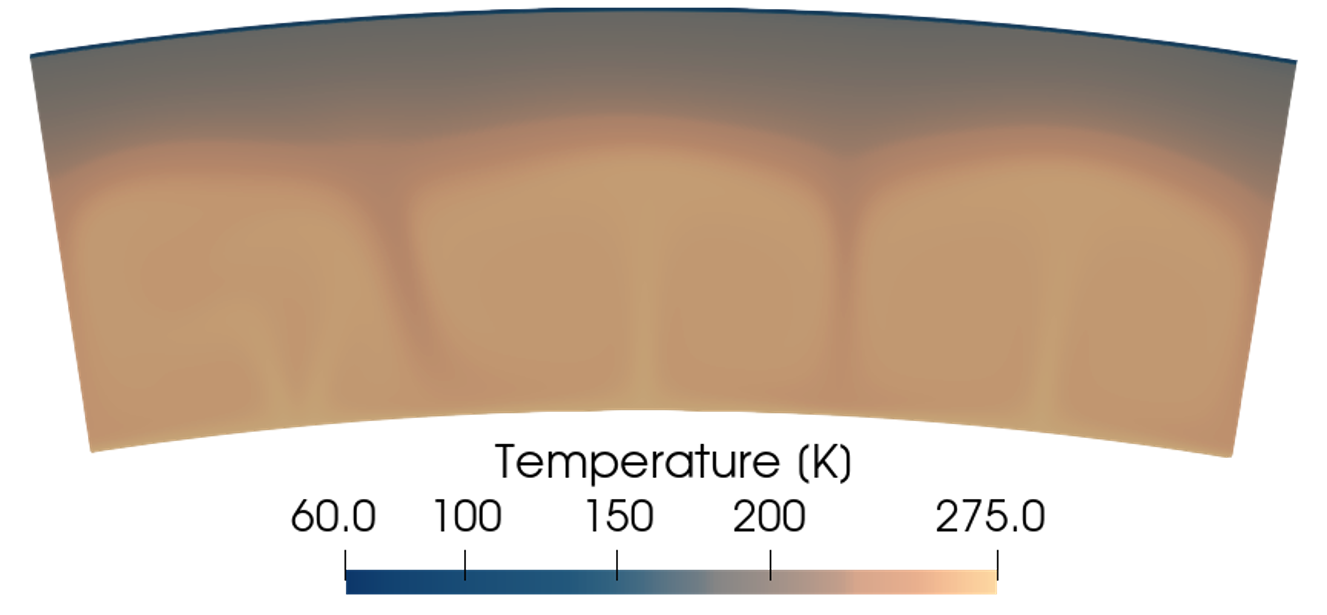

Fig. 1: Modeled convection pattern in an ice shell with an ice shell thickness of 25 km, a porous layer thickness of 250 m, and porous layer thermal conductivity of 0.025 Wm-1K-1.

Fig. 2: Laterally averaged profiles for Fig. 1 showing a) temperature with depth b) 2-way radar attenuation under low-loss pure water ice assumption c) 2-way radar attenuation under high-loss 300 µmol chloride assumption. We assume here an attenuation limit of 100 dB [16].

Our results show that the porous layer thickness and its distribution have a first order effect on the thermal state and dynamics of the ice shell. Regions covered by a thick porous layer are characterized by a warm ice shell temperature and thus a lower viscosity, becoming more prone to undergo solid-state convection (Fig. 1). The vigor of convection depends on both the temperature-dependent ice shell viscosity and the temperature difference across the ice shell. While a thick porous layer would result in a low ice shell viscosity, thus increasing the convection vigor, such thick porous layers lead to an almost isothermal ice shell, due to their strong insulation, which, in turn, decreases the convection vigor. In ice shell regions covered by a thick porous layer, the penetration depth of a radar sounder is limited (Fig. 2), but as discussed in a recent study that only investigated a purely conductive ice shell [6], the high temperatures obtained in this case may lead to the formation of shallow brines detectable by radar measurements.

Next, we will increase the angular size of our models and allow the ice-ocean interface at the lower boundary to vary to capture spatial variations of the ice shell thickness. The upper part of the computational domain in our model will be treated as the solid ice shell, while the lower part will mimic a water ocean layer with a lower viscosity. The viscosity of the water ocean will be set to several orders of magnitude lower than that of the overlying ice shell. We will vary the viscosity contrast between the ice shell and the water layer to investigate whether ice flow can occur and possibly dampen the variations in the ice shell thickness. This will help us understand how convection can dynamically alter ice shell thickness, in contrast to previous modeling which assumes a purely conductive ice shell [6].

In future models, we will extend our models to include the effects of chemical impurities and tidal forces on the thermal state of Enceladus’ ice shell. We will track the redistribution of chemical anomalies due to solid-state convection in the ice shell. To this end, we will test different initial distributions of chemical heterogeneities and include tidal heating. Both the presence of chemical anomalies and tidal heating can affect the convection vigor and the convection pattern that characterizes large-scale dynamics in the ice shell. We will compare these more complex models with previous chemically homogeneous models in order to examine the effects of chemical anomalies and tidal heating on the thermal and dynamical state of the ice shell, and on the 2-way radar attenuation.

References:

[1] Choblet et al. (2021), Experimental Astronomy; [2] Porco et al. (2006), Science; [3] Postberg et al. (2009), Nature; [4] Martin et al. (2023), Icarus; [5] Souček et al. (2023), GRL; [6] Byrne et al. (2024), JGR:Planets; [7] Hüttig et al., (2013), PEPI; [8] Laneuville et al. (2013), JGR:Planets; [9] Tosi et al. (2015), GRL; [10] Plesa et al. (2016), JGR:Planets; [11] Rückriemen-Bez et al. (2023), Galilean Moons Workshop; [12] Plesa et al. (2023), Galilean Moons Workshop; [13] Hemingway & Mittal (2019), Icarus; [14] Seiferlin et al. (1996), PSS; [15] Ferrari et al. (2021), A&A; [16] Kalousova et al. (2017), JGR:Planets.

How to cite: DeMers, E., Byrne, W., Plesa, A.-C., Benedikter, A., and Hussmann, H.: Modeling Convection Dynamics in the Ice Shell of Enceladus, EPSC-DPS Joint Meeting 2025, Helsinki, Finland, 7–12 Sep 2025, EPSC-DPS2025-2027, https://doi.org/10.5194/epsc-dps2025-2027, 2025.