OPS4

Exploring the Saturn system

Conveners:

Carly Howett,

Axel Hagermann

|

Co-conveners:

Georgina Miles,

Günter Kargl,

Katharina Otto,

Stephan Zivithal

Orals TUE-OB2

|

Tue, 09 Sep, 09:30–10:30 (EEST) Room Mars (Veranda 1)

Orals TUE-OB3

|

Tue, 09 Sep, 11:00–12:24 (EEST) Room Mars (Veranda 1)

Orals TUE-OB5

|

Tue, 09 Sep, 15:00–16:00 (EEST) Room Mars (Veranda 1)

Orals TUE-OB6

|

Tue, 09 Sep, 16:30–17:54 (EEST) Room Mars (Veranda 1)

Orals WED-OB5

|

Wed, 10 Sep, 15:00–16:00 (EEST) Room Neptune (rooms 22+23)

Posters TUE-POS

|

Attendance Tue, 09 Sep, 18:00–19:30 (EEST) | Display Tue, 09 Sep, 08:30–19:30 Lämpiö foyer, L10–28

Tue, 09:30

Tue, 11:00

Tue, 15:00

Tue, 16:30

Wed, 15:00

Tue, 18:00

Session assets

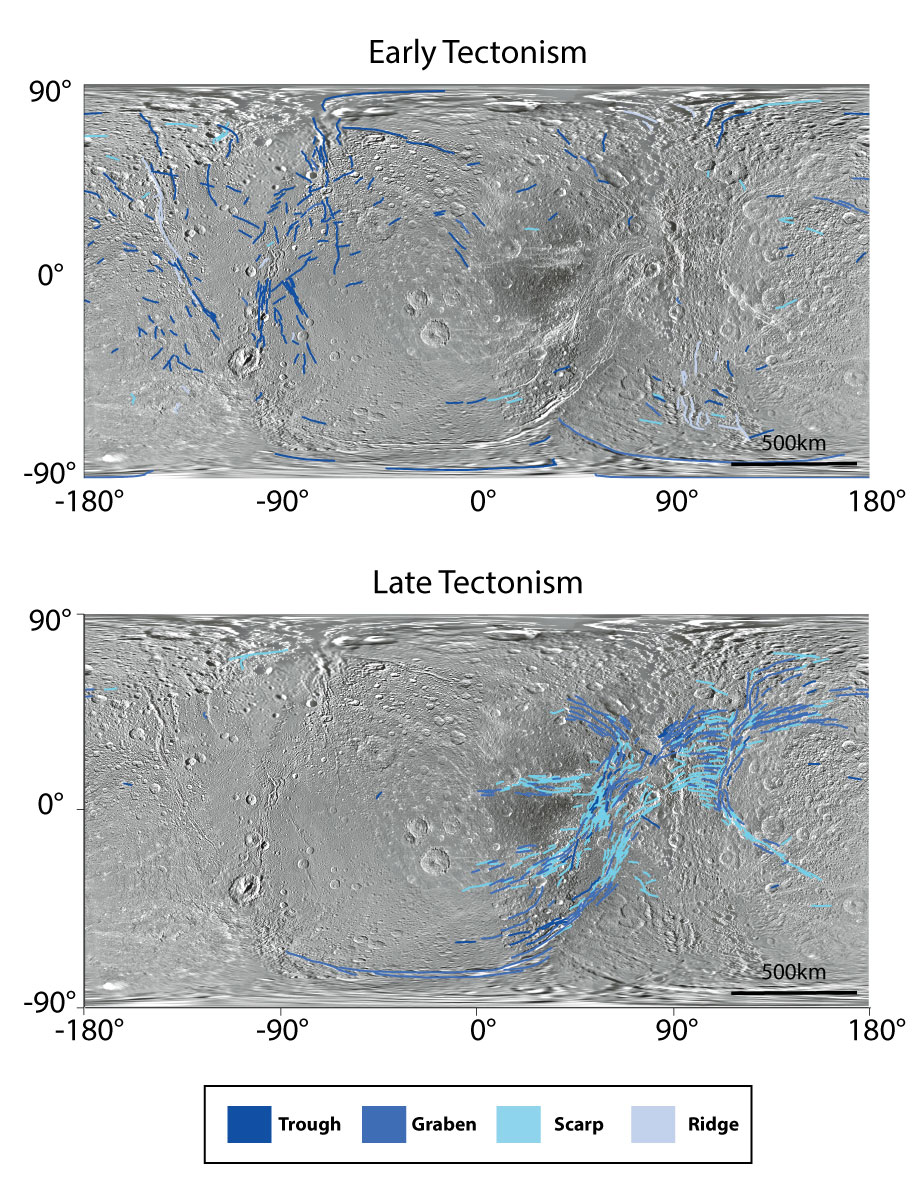

Surface

09:30–09:42

|

EPSC-DPS2025-1307

|

ECP

|

On-site presentation

09:42–09:54

|

EPSC-DPS2025-1620

|

On-site presentation

09:54–10:06

|

EPSC-DPS2025-1176

|

ECP

|

On-site presentation

10:06–10:18

|

EPSC-DPS2025-1378

|

ECP

|

On-site presentation

10:18–10:30

|

EPSC-DPS2025-797

|

ECP

|

On-site presentation

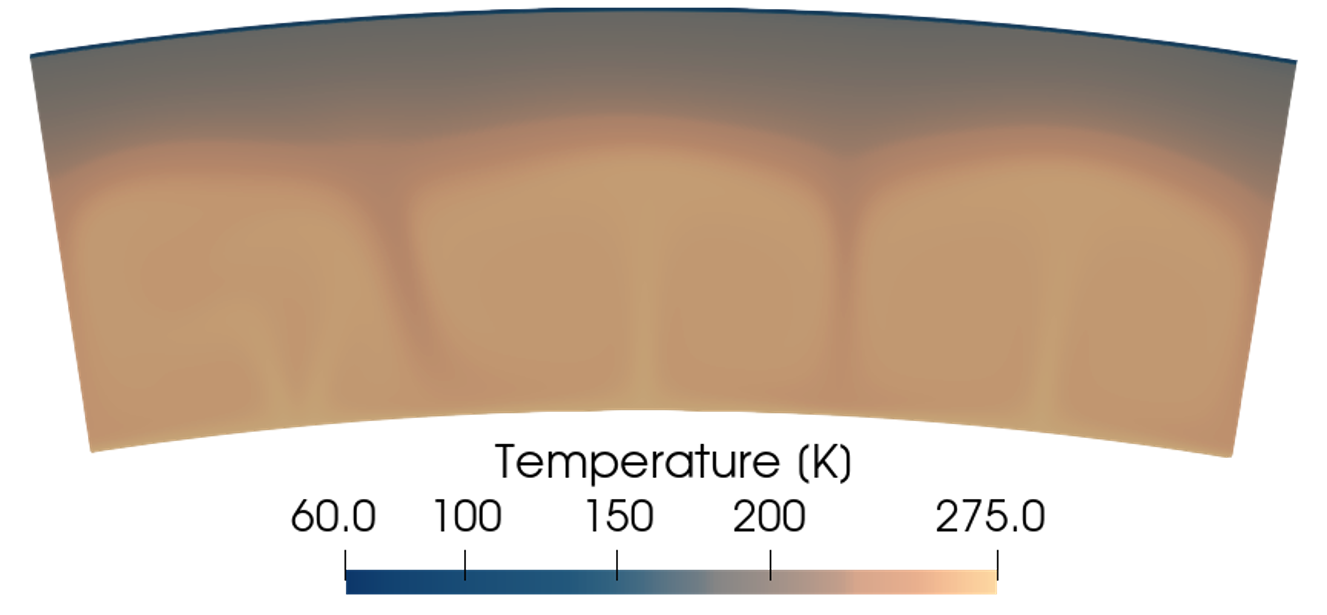

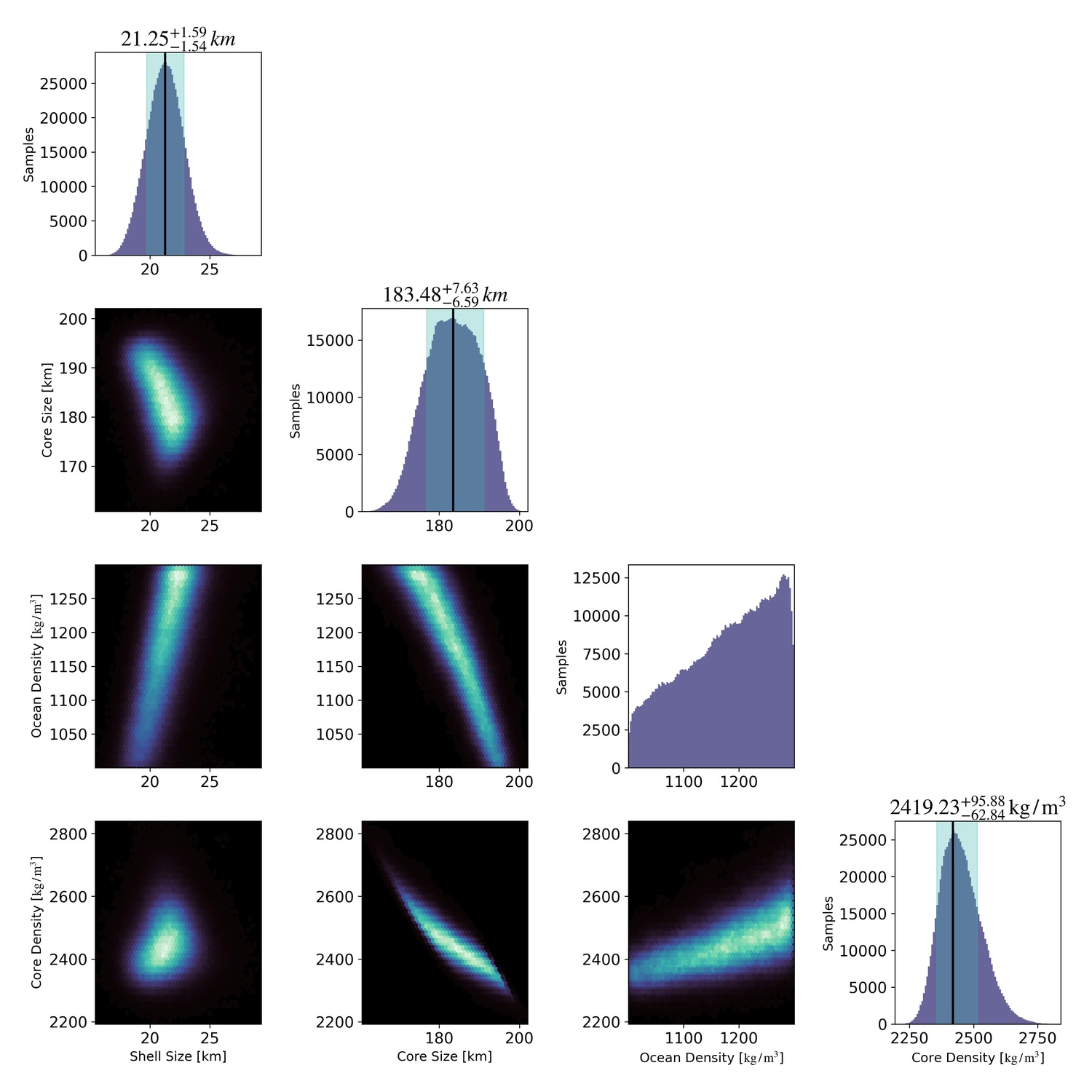

Enceladus Interior and Plumes

11:00–11:12

|

EPSC-DPS2025-902

|

On-site presentation

11:12–11:24

|

EPSC-DPS2025-351

|

On-site presentation

11:24–11:36

|

EPSC-DPS2025-2003

|

On-site presentation

11:36–11:48

|

EPSC-DPS2025-829

|

On-site presentation

12:00–12:12

|

EPSC-DPS2025-1885

|

ECP

|

On-site presentation

12:12–12:24

|

EPSC-DPS2025-1124

|

Virtual presentation

Enceladus and Friends

15:00–15:12

|

EPSC-DPS2025-618

|

On-site presentation

15:12–15:24

|

EPSC-DPS2025-330

|

On-site presentation

15:24–15:36

|

EPSC-DPS2025-1638

|

On-site presentation

15:36–15:48

|

EPSC-DPS2025-1800

|

ECP

|

On-site presentation

15:48–16:00

|

EPSC-DPS2025-232

|

ECP

|

On-site presentation

Impact Gardening on Iapetus and Insights into the Evolution of the Extreme Albedo Dichotomy

(withdrawn)

Saturnian Satellites

16:30–16:42

|

EPSC-DPS2025-433

|

ECP

|

On-site presentation

16:42–16:54

|

EPSC-DPS2025-1117

|

On-site presentation

16:54–17:06

|

EPSC-DPS2025-1134

|

ECP

|

On-site presentation

17:06–17:18

|

EPSC-DPS2025-879

|

ECP

|

On-site presentation

17:18–17:30

|

EPSC-DPS2025-115

|

On-site presentation

17:30–17:42

|

EPSC-DPS2025-1187

|

ECP

|

On-site presentation

17:42–17:54

|

EPSC-DPS2025-810

|

On-site presentation

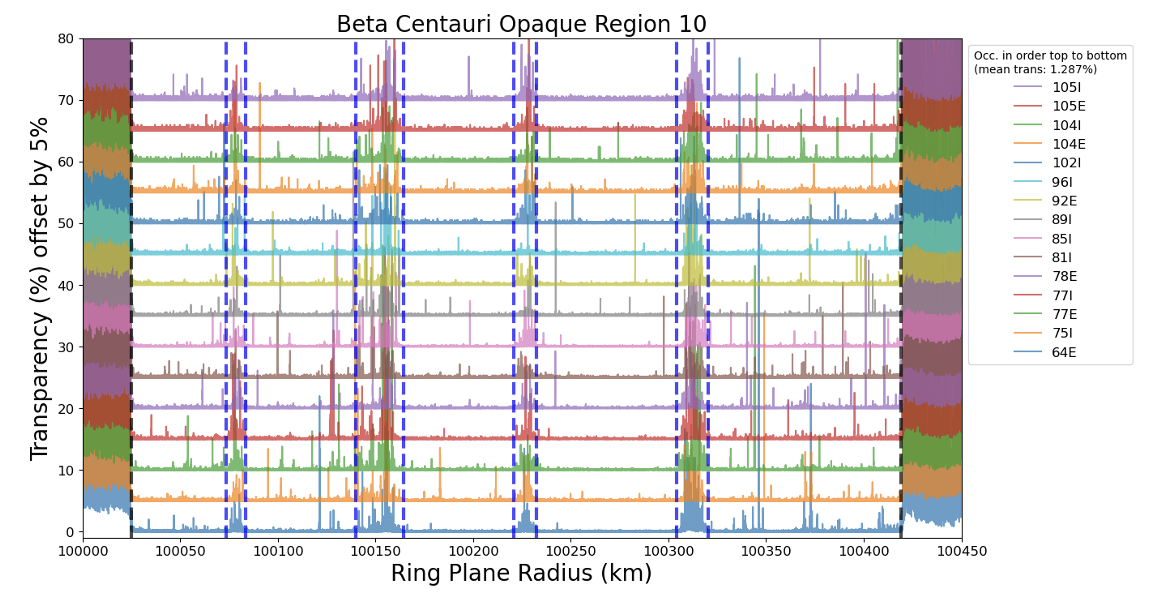

Rings

15:00–15:12

|

EPSC-DPS2025-1572

|

ECP

|

On-site presentation

15:12–15:24

|

EPSC-DPS2025-1052

|

On-site presentation

15:24–15:36

|

EPSC-DPS2025-36

|

On-site presentation

15:36–15:48

|

EPSC-DPS2025-336

|

Virtual presentation

Saturnian Satellites

L10

|

EPSC-DPS2025-1258

|

On-site presentation

L11

|

EPSC-DPS2025-855

|

On-site presentation

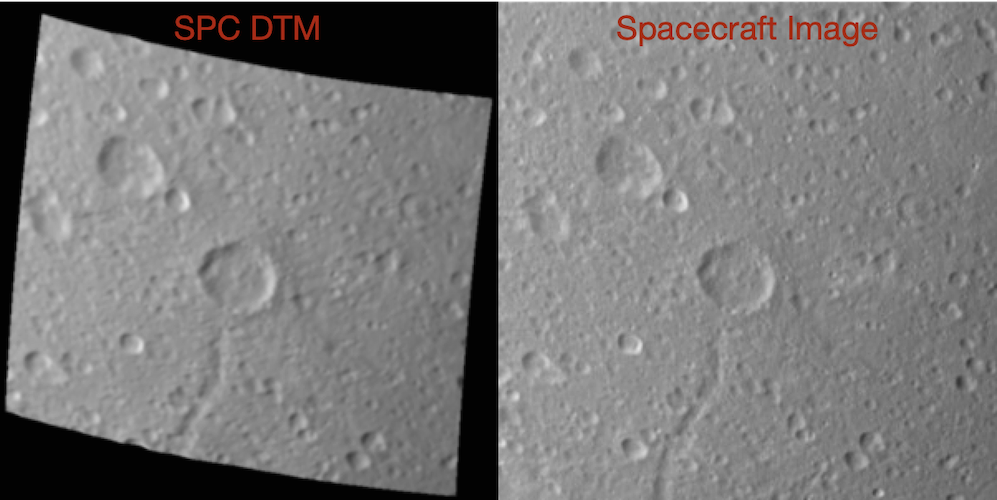

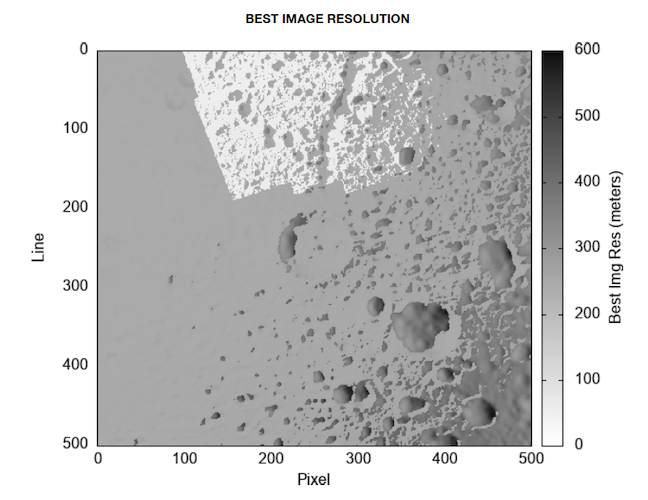

Enceladus Surface

L13

|

EPSC-DPS2025-400

|

On-site presentation

L15

|

EPSC-DPS2025-264

|

ECP

|

On-site presentation

L16

|

EPSC-DPS2025-544

|

On-site presentation

L17

|

EPSC-DPS2025-1574

|

On-site presentation

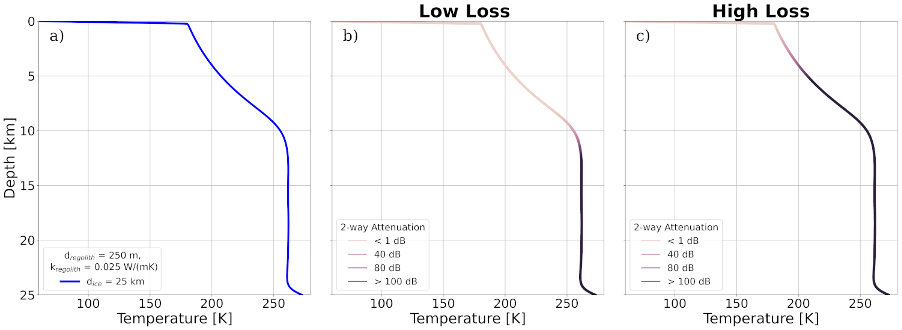

Enceladus Sub-surface and Interior

L18

|

EPSC-DPS2025-2027

|

On-site presentation

L19

|

EPSC-DPS2025-1531

|

On-site presentation

L20

|

EPSC-DPS2025-1889

|

ECP

|

On-site presentation

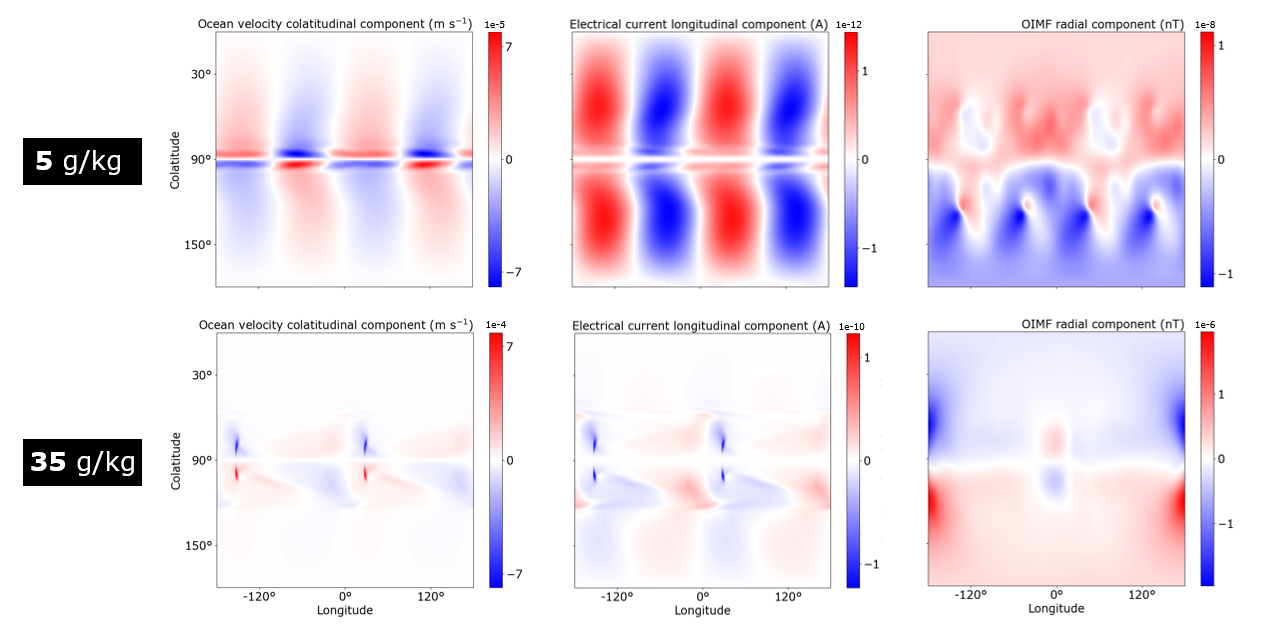

Plumes, Induction, Ionospheres and Magnetospheres

L21

|

EPSC-DPS2025-675

|

ECP

|

On-site presentation

Detecting cellular biosignatures from Sphingopyxis alaskensis exposed to Enceladus plume and surface conditions

(withdrawn)

L22

|

EPSC-DPS2025-963

|

On-site presentation

L24

|

EPSC-DPS2025-1196

|

ECP

|

On-site presentation

L25

|

EPSC-DPS2025-1903

|

On-site presentation

Rings

L27

|

EPSC-DPS2025-1769

|

ECP

|

On-site presentation

Evolution of Viscous Overstability in Saturn’s Rings:Insights from Large-Scale N-Body Simulations

(withdrawn after no-show)

L28

|

EPSC-DPS2025-397

|

On-site presentation