- Purdue University, Department of Earth, Atmospheric, and Planetary Sciences, West Lafayette, Indiana, United States of America (ipamerle@purdue.edu)

Introduction: The differentiation state of a planetary body affects evolution and thermal structure, but the differentiation state of Callisto remains unclear. Our understanding of Callisto relies on data retrieved from NASA’s Galileo mission, which measured the moment of inertia (MOI) under an assumption of hydostaticity [1]. Models of Callisto’s internal structure with this inferred MOI were used to suggest a partially differentiated interior without full ice/rock separation [1]. Other works, however, argued that an undifferentiated Callisto is improbable because partial differentiation would lead to a runaway differentiation process [2].

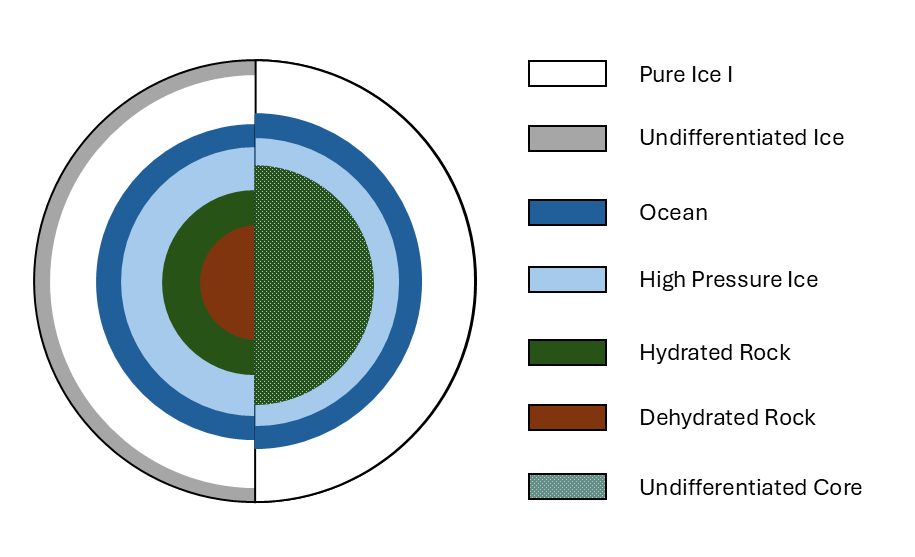

Interior structures that could explain the inferred high MOI value include: (1) a partially differentiated interior, (2) nonhydrostatic components on a differentiated Callisto, and (3) an undifferentiated outer shell overlying a fully differentiated interior, which we focus on here. An undifferentiated shell could result from a differentiated interior with full ice/rock separation but a melting front that does not reach the shallow subsurface (Fig. 1) and has been proposed for Uranian moons [3]. The undifferentiated shell would be a dense mixture of ice and rock, which would lead to a high MOI value with a more differentiated interior. Although this undifferentiated outer shell would have a negative density gradient, foundering of the shell is unlikely to occur [4].

Here, we investigate the evolution of Callisto’s surface assuming an undifferentiated outer shell overlying a pure-ice mantle. The undifferentiated shell would behave as a high-density, high-viscosity layer, and the pure-ice mantle would act as a low-density, low-viscosity layer, analogous to ice tectonics on Ceres [5]. Topography and density differences would cause differential stresses that could drive upward deformation. Ice tectonic deformation would uplift the crater floor and may be another pathway to the shallow, anomalous craters observed by [6] that has been suggested to be the result of viscous relaxation [7].

Methods: We simulate the evolution of topography on Callisto assuming an undifferentiated shell using the finite element method (FEM). We simulate an undifferentiated ice-rock layer (50% ice, 50% silicates [2]) on top of a pure ice layer. The interfaces between layers are flat, and the initial topography of the crater is taken from [7], which extrapolated depth-diameter ratios of smaller complex craters (<26 km diameter) on Callisto. Both layers deform as viscoelastic materials with non-Newtonian rheologies (grain boundary sliding and dislocation creep) [8]. The thermal profile is calculated for surface temperatures of 125 K and 110 K, with a constant heat flux of 15 mW/m2 [7].

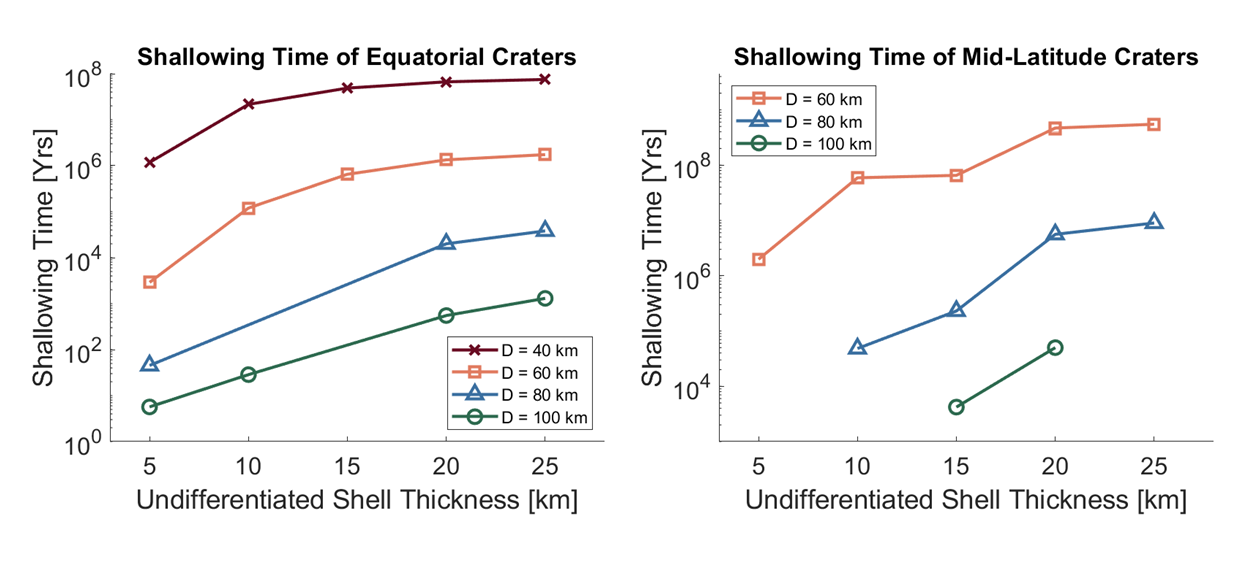

We vary the undifferentiated layer thickness (5–25 km) for multiple crater diameters (10–100 km). As ice tectonics will uplift crater floors, we measure the time it takes for craters to reach current depths from a deeper initial depth to test if an undifferentiated shell could cause the shallow, observed craters [6].

Results: We found that craters ≥40 km in diameter in all undifferentiated shell thickness values deform to their currently observed states in <108 yrs at equatorial surface temperatures (Fig. 2). Craters ≤20 km in diameter experience little deformation in 2 Gyrs. We also tested mid-latitude surface temperatures and found craters ≥60 km in diameter achieve their observed depths in <1 Gyr (Fig. 2).

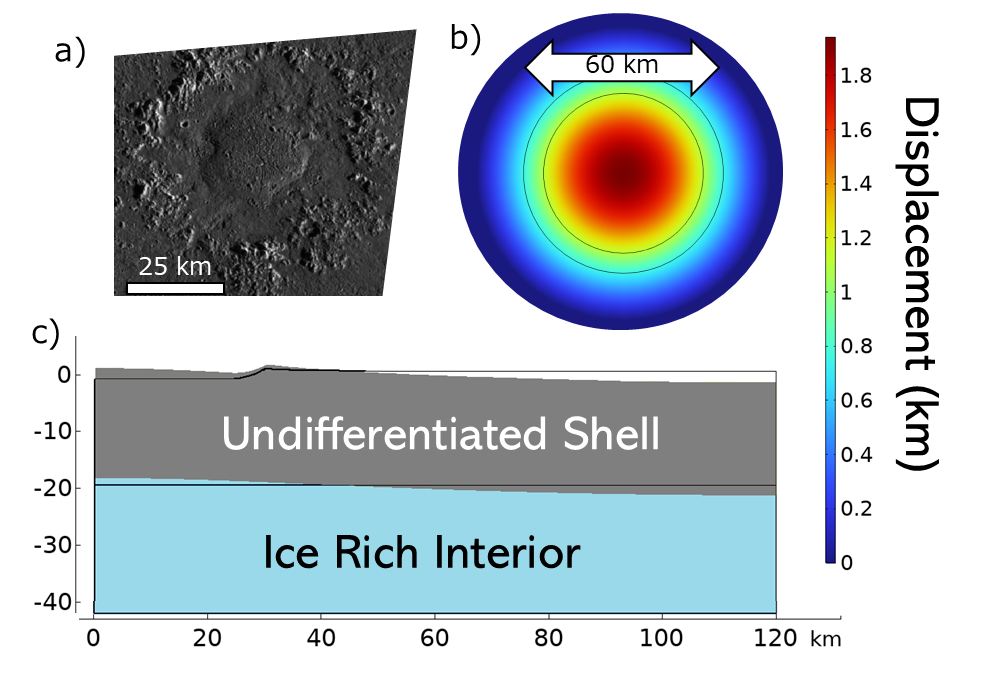

In simulations where deformation is highly favored (large craters, thin shells), our simulations begin to produce broad topographic domes at the center of the craters (Fig. 3). These domes are shallow and comprise most of the crater floor.

Discussion: Our simulations predict shallow Callisto craters that are consistent with observed crater depths in some of the model parameter space. Our smallest craters (≤20 km in diameter) do not deform even under the most favorable conditions. The shallow, anomalous crater transition diameter is ~26 km on Callisto [6], so the smallest craters begin the simulation with depths consistent with observations. Our current results show only the 40 km diameter craters at colder surface temperatures are unable to reproduce observations after 2 Gyrs. Future work that implements porosity into the undifferentiated shell will increase thermal conductivity and may help drive further deformation.

The domes produced in some of our simulations are different than central pit/domes found in many craters across Ganymede and Callisto [6]. Such central pit/domes are laterally smaller with steeper slopes. The domes produced in our simulations are morphologically distinct from these and would be more difficult to observe with low resolution data due to the shallow slopes. High resolution images of Doh craters reveal domes that may be consistent with our model predictions and an undifferentiated outer shell (Fig. 3).

Conclusions: We use viscoelastic FEM simulations to investigate how topography on Callisto would evolve in an undifferentiated outer shell. We found that ice tectonics from a pure ice layer underneath an undifferentiated ice shell can reproduce observed crater depth-diameter ratios (Fig. 2). Scenarios that favor deformation may produce subtle, broad topographic domes in craters, which may require high resolution data to observe (e.g., Doh crater, Fig. 3). The abundance or lack of these broad domes on Callisto can provide a test for the JUICE mission to rule out or favor an undifferentiated shell on Callisto.

References: [1] Anderson et al., Nature 387, 264–266 (1997). [2] Mueller & McKinnon, Icarus 76, 437–464 (1988). [3] Castillo-Rogez et al., JGR: Planets 128 (2023). [4] Miyazaki & Stevenson, PSJ 5, 192 (2024). [5] Bland et al., Nat. Geo 12, 797–801 (2019). [6] Schenk, Nature 417, 419–421 (2002). [7] Bland & Bray, Icarus 408, 115811 (2024). [8] Durham et al., JGR Planets 102, 16293–16302 (1997).

Figure 1: Left, a fully differentiated interior with an undifferentiated shell. Right, a partially differentiated core without full separation of ice and rock.

Figure 2: Shallowing time vs undifferentiated shell thicknesses for different crater sizes. Left, surface temperature of 125 K. Right, surface temperature of 110 K.

Figure 3: a) Doh crater (~60 km diameter). b) arial view of 60 km diameter simulated crater (20 km thick undifferentiated shell) with the two rings denoting the rim and floor. Color shows upward deformation. c) profile of the simulated crater showing the undifferentiated and pure ice.

How to cite: Pamerleau, I. and Sori, M.: Insights into Callisto’s interior: shallow craters and broad domes as a test for JUICE. , EPSC-DPS Joint Meeting 2025, Helsinki, Finland, 7–12 Sep 2025, EPSC-DPS2025-933, https://doi.org/10.5194/epsc-dps2025-933, 2025.