TP8

The Multi-Scale Physics of Surface-Bounded Exosphere and Surface Interactions

Conveners:

Alexander Peschel,

Sébastien Verkercke,

Rozenn Robidel,

Liam Morrissey,

Menelaos Sarantos

Orals TUE-OB3

|

Tue, 09 Sep, 11:00–12:30 (EEST) Room Neptune (rooms 22+23)

Posters MON-POS

|

Attendance Mon, 08 Sep, 18:00–19:30 (EEST) | Display Mon, 08 Sep, 08:30–19:30 Finlandia Hall foyer, F71–75

Key Themes:

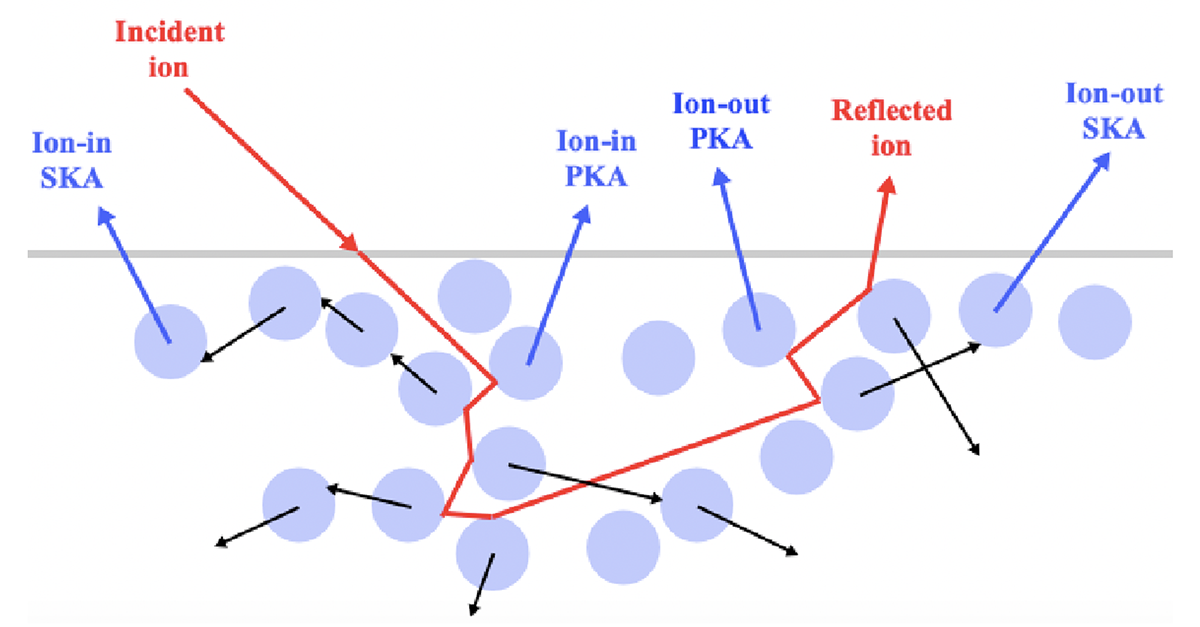

• Atomistic Modeling: Utilizing atomistic approaches to provide insights and possible validations for larger-scale processes.

• Parameter Identification: Determining key parameters for surface-bounded exospheres and surface interactions at varying scales will inform further atomistic research and guide observational and laboratory experiments.

• Surface–Exosphere Linkages: Explaining the connections between surface-bounded exospheres and their respective surfaces, including compositional and topographic effects.

• Comparative Investigations: Encouraging comparative studies across different planetary bodies (including icy moons) to enhance our knowledge of underlying processes.

By addressing these key themes, the session explicitly links micro-scale processes to macro-scale dynamics, thereby bridging scales and enriching our integrated understanding of exosphere–surface interactions. We particularly encourage early career scientists to submit an abstract for an oral presentation.

Session assets

11:00–11:03

Session Introduction

11:03–11:15

|

EPSC-DPS2025-614

|

ECP

|

On-site presentation

11:15–11:27

|

EPSC-DPS2025-102

|

ECP

|

On-site presentation

11:27–11:39

|

EPSC-DPS2025-1213

|

ECP

|

On-site presentation

11:39–11:51

|

EPSC-DPS2025-118

|

ECP

|

On-site presentation

11:51–12:06

|

EPSC-DPS2025-1133

|

ECP

|

On-site presentation

12:06–12:18

|

EPSC-DPS2025-83

|

ECP

|

On-site presentation

12:18–12:30

|

EPSC-DPS2025-451

|

ECP

|

On-site presentation

F71

|

EPSC-DPS2025-1690

|

ECP

|

On-site presentation

F72

|

EPSC-DPS2025-1091

|

ECP

|

On-site presentation

F73

|

EPSC-DPS2025-18

|

On-site presentation

F74

|

EPSC-DPS2025-748

|

On-site presentation

F75

|

EPSC-DPS2025-1193

|

ECP

|

On-site presentation