Poster presentations and abstracts

Impact processes shaped the solar system and modify planetary surfaces until today. This session aims at understanding planetary impact processes at all scales in terms of shock metamorphism, dynamical aspects, geochemical consequences, environmental effects and biotic response, and cratering chronology. Naturally, advancing our understanding of impact phenomena requires a multidisciplinary approach, which includes (but it is not limited to) observations of craters, strewn field or airbursts, numerical modelling, laboratory experiments, geologic and structural mapping, remote sensing, petrographic analysis of impact products, and isotopic and elemental geochemistry analysis.

We welcome presentations across this broad range of study and particularly encourage work that bridges the gap between the investigative methods employed in studying planetary impact processes at all scales.

Session assets

The Cretaceous-Paleogene (K-Pg) mass extinction, 66.0 Ma (Renne et al., 2013), was one of the most important events in the Phanerozoic, severely altering the evolutionary and ecological history of biotas (Schulte et al., 2010). This extinction was caused by paleoenvironmental changes associated with the impact of an asteroid (Alvarez et al., 1980) on the Yucatán carbonate-evaporite platform in the southern Gulf of Mexico, which formed the Chicxulub impact crater (Hildebrand et al., 1991). Prolonged impact winter resulting in global darkness and cessation of photosynthesis, and acid rain have been considered as major killing mechanisms on land and in the oceans. Major animal groups disappeared across the boundary (e.g., the nonavian dinosaurs, marine and flying reptiles, ammonites, and rudists), and other groups suffered severe species level (but not total) extinction, including planktic foraminifera, and calcareous nannofossils. Other groups, including many deep sea benthic organisms, did not experience extinctions but did undergo observable changes in abundance, diversity and composition (Schulte et al., 2010). Thus, the end-Cretaceous impact event had a major importance in the evolution of life in the Earth from the Paleogene.

To evaluate the significance of the asteroid impact in the K-Pg mass extinction it is important to study the impact crater itself. On this challenge, in April and May 2016, a joint expedition of the International Ocean Discovery Program and the International Continental Scientific Drilling Program Expedition 364 drilled into the Chicxulub peak ring and recovered ~130 m of impact deposits which provide a record of the recovery of life in a sterile zone. Analysis of trace fossils reveals the effect of impact-driven paleoenvironmental changes on the macrobenthic community, a group comparatively poorly known. Trace fossils, as records of macrobenthic tracemakers, are closely related to paleoenvironmental conditions; ichnological research is being increasingly used as a tool to study the “Big Five” mass extinctions, with special attention to the K-Pg impact mass extinction event (Lavandeira et al., 2016).

Ichnological data, integrated with planktic foraminifera and calcareous nannoplankton datasets, revealed that life reappeared in the basin just years after the impact. Clear, discrete trace fossils, including Planolites and Chondrites, are registered in the sediments deposited just immediately after the event (Lowery et al., 2018). Thus, proximity to the impact did not delay recovery and that there was therefore no impact-related environmental control on recovery (Lowery et al., 2018). To follow up on this study, ichnological research has been conducted to investigate the initial diversification, evolution, restructuring, and stabilization of the macrobenthic community following the impact event (Rodríguez-Tovar et al., 2020). After the initial recovery a first phase of diversification is recognized, extended to ~45 k.y. after the K-Pg impact event, characterized by the increase in the abundance and size of the trace fossils and the development of an initial community with Planolites, Chondrites, and Palaeophycus, as well as a shallow indeterminate infauna. Subsequently, a phase of stabilization is registered in the infaunal community, with changes only in relative abundance between ichnotaxa, until ~640–700 k.y. into the Paleocene. At this time, following the prolonged phase of stabilization, a second phase of diversification is observed, characterized by the appearance of well-developed Zoophycos. This diversification marks the beginning of the highest diversity, abundance, and size of traces, with a community of Zoophycos, Chondrites, Planolites, and Palaeophycus representing the establishment of a well-developed tiered assemblage within ~700 k.y. This community is maintained during the phase of consolidation/dominance, through at least ~1.25 m.y. after the K-Pg boundary.

These data support the fast progression of recovery in the macrobenthic tracemaker community in the impact area, with a total reestablishment ~700 k.y. after the impact event. This is rapid in comparison with other mass extinction events, as that occurred at the end-Permian, which took millions of years (Twitchett, 2006). Such rapid recovery demonstrates the ephemeral nature of environmental change at the K-Pg boundary compared to earlier mass extinctions driven by fundamentally slower mechanisms.

Hildebrand, A.R., Penfield, G.T., Kring, D.A., Pilkington, M., Camargo, A.Z., Jacobsen, S.B., and Boynton, W.V., 1991, Chicxulub Crater: a possible Cretaceous/Tertiary boundary impact crater on the Yucatán Peninsula, Mexico: Geology, v. 19, 867–871.

Lowery, C.M., Bralower, T.J., Owens, J.D., Rodríguez-Tovar, F.J., Jones, H., Smit, J., Whalen, M.T., Claeys, P., Farley, K., Gulick, S.P.S., Morgan, J.V., Green, S., Chenot, E., Christeson, G.L., Cockell, C.S., Coolen, M.J.L., Ferrière, L., Gebhardt, C., Goto, K., Kring, D.A., Lofi, J., Ocampo-Torres, R., Perez-Cruz, L., Pickersgill, A.E., Poelchau, M.H., Rae, A.S.P., Rasmussen, C., Rebolledo-Vieyra, M., Riller, U., Sato, H., Tikoo, S.M., Tomioka, N., Urrutia-Fucugauchi, J., Vellekoop, J., Wittmann, A., Xiao, L., Yamaguchi, K.E., and Zylberman, W., 2018, Rapid recovery of life at ground zero of the end Cretaceous mass extinction: Nature, v. 558, 288–291.

Renne, P.R., Deino, A.L., Hilgen, F.J., Kuiper, K.F., Mark, D.F., Mitchell, W.S., Morgan, L.E., Mundil, R., and Smit, J., 2013, Time scales of critical events around the Cretaceous-Paleogene boundary: Science, v. 339, p. 684–687.

Rodríguez-Tovar, F.J., Lowery, C.M., Bralower, T.J., Gulick, S.P.S., Jones, H.L., 2020.Rapid macrobenthic diversification and stabilization after the end-Cretaceous mass extinction event: Geology (in press).

Schulte, P., Alegret, L., Arenillas, I., Arz, J.A., Barton, P.J., Bown, P.R., Bralower, T.J., Christeson, G.L., Claeys, P., Cockell, C.S., Collins, G.S., Deutsch, A., Goldin, T.J., Goto, K., Grajales-Nishimura, J.M., Grieve, R.A.F., Gulick, S.P.S., Johnson, K.R., Kiessling, W., Koeberl, C., Kring, D.A., MacLeod, K.G., Matsui, T., Melosh, J., Montanari, A., Morgan, J.V., Neal, C.R., Nichols, D.J., Norris, R.D., Pierazzo, E., Ravizza, G., Rebolledo-Vieyra, M., Reimold, W.U., Robin, E., Salge, T., Speijer, R.P., Sweet, A.R., Urrutia-Fucugauchi, J., Vajda, V., Whalen, M.T., and Willumsen, P.S., 2010, The Chicxulub asteroid impact and mass extinction at the Cretaceous-Paleogene boundary: Science, v. 327, p. 1214–1218.

Twitchett, R.J., 2006, The palaeoclimatology, palaeoecology and palaeoenvironmental analysis of mass extinction events: Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology, v. 232, p. 190–213.

How to cite: Rodriguez Tovar, F. J., Lowery, C. M., Bralower, T. J., Gulick, S. P. S., and Jones, H. L.: The end-Cretaceous mass extinction event at the impact area: A rapid macrobenthic diversification and stabilization, Europlanet Science Congress 2020, online, 21 Sep–9 Oct 2020, EPSC2020-65, https://doi.org/10.5194/epsc2020-65, 2020.

The series of methane detection and non-detection in the atmosphere of Mars over the last two decades has raised numerous questions about methane generation and destruction mechanisms, which still remain unexplained. It has been suggested that Martian methane could have a biological origin and be generated by organisms living in the subsurface where conditions are more hospitable [1]. Methane could also be produced through several abiologic processes, including Fischer-Tropsch Type (FTT) reactions where H2 reacts with CO2 in the presence of a metal catalyst [2]. The H2 necessary for the FTT reactions can be produced by several processes and notably by serpentinization [3]. Many of the proposed generation mechanisms for methane would take place hundreds of meters to several kilometers deep in the crust of Mars. Once produced, methane can migrate upwards and be either directly released at the surface or trapped in subsurface reservoirs, such as clathrate hydrates, where it could accumulate over long time before being episodically liberated during destabilizing events. These phenomena leading to surface degassing imply a change in temperature/pressure conditions of the methane reservoirs and are multiple: faulting and landslide generated by seismicity, impact, climatic changes...

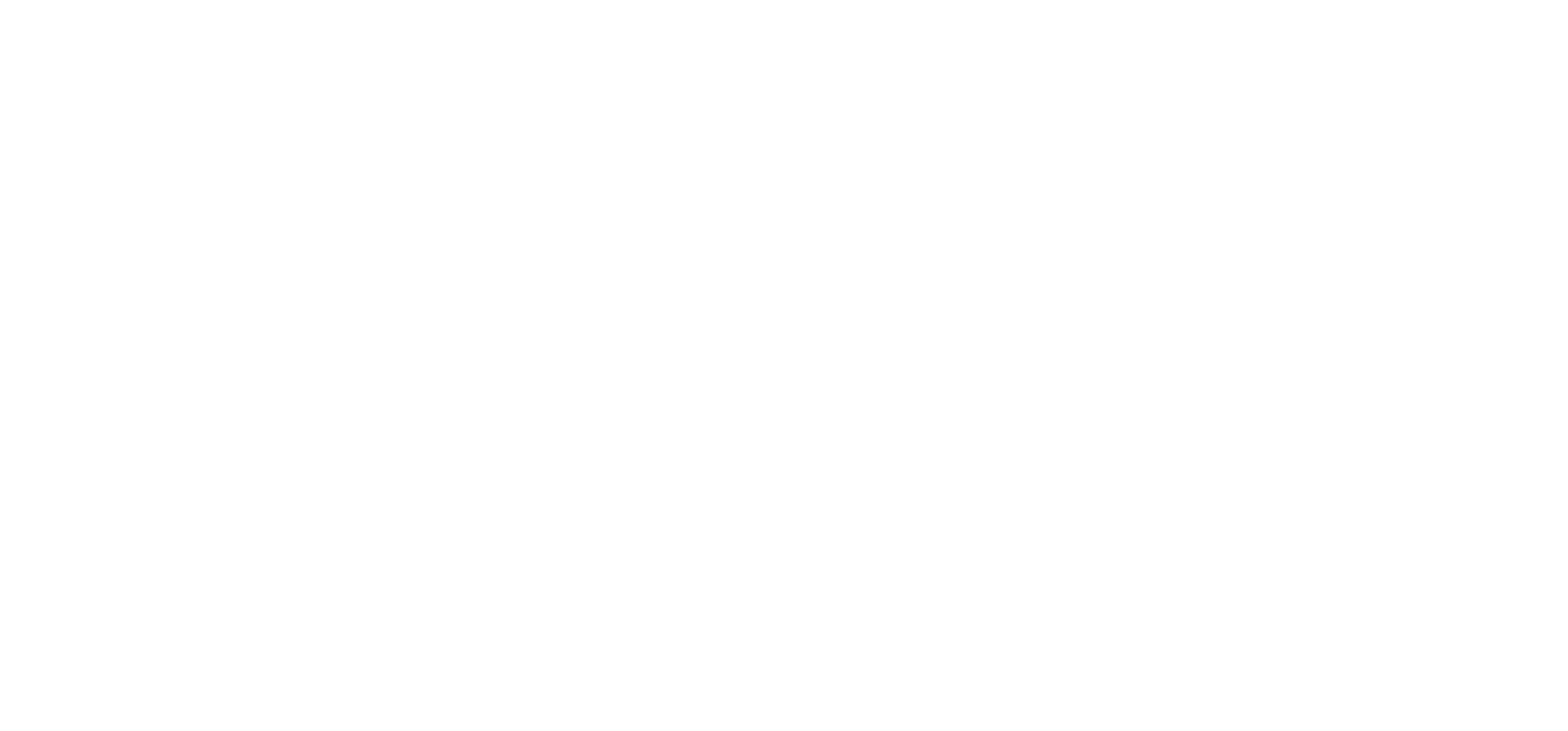

In this study, we investigate the capacity of small-sized (a few tens to a few hundred meters diameter) impact craters to thermally penetrate the Martian ground and release methane through the dissociation of subsurface clathrate reservoirs. The impacts of small meteorite are more frequent on present-day Mars and could represent a likely process that would sporadically destabilize shallow gas reservoirs, inducing the degassing of methane in the atmosphere of the planet. We use a one-dimensional finite difference thermal model of the subsurface to calculate the depth of stable methane clathrate hydrates. The impact-induced heat, calculated using the Murnaghan equation of state, is then added to geothermal temperatures to obtain the post-impact temperature distributions similarly to [4]. We apply our model to different case studies in order to constrain the impactor radius, velocity and impact angle required to destabilize a subsurface clathrate layer that would discharge methane amounts corresponding to the observations.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Fonds de la Recherche Scientifique - FNRS and by the Research Foundation Flanders (FWO) under Grant n° EOS-30442502.

References

[1] Atreya, S. K. et al., Planet. Space Sci. 55, 358-369, 2007.

[2] Oehler, D. Z. and Etiope, G., Astrobiology 17, 1233-1264, 2017.

[3] Oze, C. and Sharma, M., Geophys. Res. Lett. 32, 2005.

[4] Schwenzer, S. P. et al., Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 335-336, 9-17, 2012.

How to cite: Gloesener, E., Temel, O., Karatekin, Ö., Joiret, S., and Dehant, V.: Destabilization of methane clathrate hydrate by meteorite impacts on present-day Mars, Europlanet Science Congress 2020, online, 21 Sep–9 Oct 2020, EPSC2020-843, https://doi.org/10.5194/epsc2020-843, 2020.

We constructed a system of parameterized representations of impact-related processes such as crater formation, atmospheric erosion, and impact melt production in order to model how impactors of different types and a large range of sizes could affect CO2-H2O atmospheres and interiors of terrestrial planets similar to Mars, Venus, or the early Earth. Impactor-induced mass fluxes leading to e.g. atmospheric escape, delivery and outgassing are calculated assuming CO2-H2O atmospheres in order to assess under which conditions atmospheres and interiors could be depleted or enriched by processes related to impacts and associated melting or weathering.

By combining parameterized models of single impacts with statistical information about the impactor flux such as the size-frequency distribution of impactors and the cratering chronology, one can deduce evolutionary paths of the volatile contents of the atmosphere and, within limits, of the interior.

We consider rocky S-type and icy-rocky C-type asteroids as well as comets, covering a range of impactor-target density contrasts from about 1/6 to about 4/5 and a range of (absolute) impact velocities from a little less than 10 to almost 65 km/s. Impactor size ranges from 1 m to half the planetary radius. Atmospheric surface pressures cover almost five orders of magnitude, ranging from a few millibars (~modern Mars) up to 95 bar (~modern Venus). Mostly CO2-dominated atmospheric compositions representative for modern-day Mars and Venus were assumed; other gases were not included.

With regard to atmospheric effects, there is a fundamental distinction to be made between blast-producing and crater-forming impacts; the boundary that separates these two regimes is mostly defined by the deceleration of the impactor and its resistance to breakup under the ram pressure during its traversal of the atmosphere. The direct effects of the former leave the interior essentially unaffected and interact only with the atmosphere. We use the formalism by Svetsov (2007) to assess the bulk mass transfer and balance resulting from mechanical erosion of the atmosphere and the disintegration of the impactor and estimate the balance for the individual volatiles from estimates of the impactor composition. In crater-forming impacts, there are additional effects that need to be included. Ejecta can contribute to the mechanical erosion of the atmosphere (e.g., Shuvalov et al., 2014) and also produce layers of porous material with a large, reactive surface that can absorb CO2 from the atmosphere by weathering in the long-term aftermath of an impact. Moreover, they produce craters which facilitate the interior-atmosphere mass exchange.

A key process in this context is the production of impact melt, which can serve as a vehicle for volatiles between the atmosphere and the interior by either releasing or dissolving CO2 and water, depending mostly on the pressure conditions at the interface; generally outgassing is expected to be more common, but still the two volatiles may behave quite differently. Consistent with previous studies we find that CO2 is expelled from the melt much more easily than H2O and could therefore enter the atmosphere under all the conditions considered, whereas water may be retained in the melt at high atmospheric pressures.

References

- Shuvalov, V. V. et al. (2016): Determination of the height of the “meteoric explosion”. Sol. Syst. Res. 50(1), 1-12, doi: 10.1134/S0038094616010056

- Svetsov, V. V. (2007): Atmospheric erosion and replenishment induced by impacts of cosmic bodies upon the Earth and Mars. Sol. Syst. Res. 41(1), 28-41, doi: 10.1134/S0038094607010030

How to cite: Ruedas, T., Wünnemann, K., Grenfell, J. L., and Rauer, H.: Impact-atmosphere-interior interactions in terrestrial planets, Europlanet Science Congress 2020, online, 21 Sep–9 Oct 2020, EPSC2020-783, https://doi.org/10.5194/epsc2020-783, 2020.

We revisit the long-standing problem of melt generation in impacts on terrestrial planets. Traditionally, estimates of melt volumes are derived by semi-analytical models and parameterized results from hydrocode simulations that account for melt generation due to the impact-induced shock (e.g., Bjorkman and Holsapple 1987, Pierazzo at al. 1997). These so-called scaling laws take the form of a power law that connects the melt volume with impactor diameter and velocity as well as the densities of impactor and target and the internal energy of melting, which are assumed constant. While this is a valid assumption for small impacts, which encounter an essentially homogeneous target, it becomes problematic if impact-related length scales such as the depth of penetration or the size of the shocked volume approach the length scales on which the properties of the target change substantially (e.g., Miljković et al., 2013; Potter et al., 2015). On even larger scales, decompression melting can contribute significantly to melt production if the change of target properties with increasing depth is substantial (e.g., the target temperature approaches the solidus [Manske et al., in revision.]). The contribution of plastic work to melt production should also be taken into account in impact scenarios with impactor speeds lower than 15 km/s (Kurosawa and Genda 2018, Melosh and Ivanov 2018).

We revisit this problem with a set of generic models of terrestrial planets in which we consider the interdependencies between certain properties of the target planet, impact parameters, and the characteristics of impact melt production. We calculate the radial thermal structure of the target planet by employing parameterized thermal evolution models that account for partial melting of the mantle and crustal growth (Tosi et al., 2017, Grott et al., 2011) and consider the heat transport in both stagnant lid and plate tectonics regimes. This leads to a heterogeneous structure of the target that we evaluate at different times and use as initial condition for the fully dynamical model of the impact itself, which is calculated with iSALE (e.g., Collins et al. 2004, Wünnemann et al. 2006). To accurately calculate impact-induced melt volumes, we developed a Lagrangian tracer-based method that accounts for the generation of impact-induced melt by shock-heating as well as decompression and plastic work due to material deformation and displacement in the course of crater formation. By these means we explore the dependence of melt production on impactor size and velocity as well as target temperature, which in turn depends on the temporal evolution of the mantle's Rayleigh number and hence on its depth and gravity. The latter in turn is a function of the mass of the target planet, which also influences the impact velocity and thus the depth of penetration of the impactor. While the models are derived for generic planets ranging in size from Moon-sized objects to super-Earths, they are also applied to planets of our Solar System, in particular Mars.

The ultimate goal is to find a comprehensive representation of these complex interdependencies. Furthermore, we aim to narrow down parameter ranges where scaling laws represent melt production satisfactorily and indicate in which scenarios target heterogeneities or melting due to decompression or plastic work affects the overall melt production significantly.

References:

Bjorkman, M. D.; Holsapple, K. A. (1987): Velocity scaling impact melt volume. Int. J. Impact Engng. 5(1-4), 155-163, doi: 10.1016/0734-743X(87)90035-2

Pierazzo, E. et al. (1997): A reevaluation of impact melt production. Icarus 127(2), 408-423, doi: 10.1006/icar.1997.5713

Miljković, K. et al. (2013). Asymmetric distribution of lunar impact basins caused by variations in target properties. Science, 342(6159), 724-726.

Potter, R. W. K. et al. (2015): Scaling of basin-sized impacts and the influence of target temperature. In: Large Meteorite Impacts and Planetary Evolution V, ed. by Osinski, G. R. and Kring, D. A., vol. 518 in Special Papers, Geological Society of America, pp. 99-113, doi: 10.1130/2015.2518(06)

Tosi, N. et al. (2017): The habitability of a stagnant-lid Earth. Astronomy & Astrophysics, 605, A71.

Grott, M. et al. (2011): Volcanic outgassing of CO2 and H2O on Mars. Earth and Planetary Science Letters, 308(3-4), 391-400.

Wünnemann, K. et al. (2006): A strain-based porosity model for use in hydrocode simulations of impacts and implications for transient crater growth in porous targets. Icarus, 180(2), 514-527.

Kurosawa, K., & Genda, H. (2018): Effects of friction and plastic deformation in shock‐comminuted damaged rocks on impact heating. Geophysical Research Letters, 45(2), 620-626.

Melosh, H. J., & Ivanov, B. A. (2018): Slow impacts on strong targets bring on the heat. Geophysical Research Letters, 45(6), 2597-2599.

How to cite: Manske, L., Plesa, A.-C., Ruedas, T., and Wuennemann, K.: The influence of interior structure and thermal state on impact melt generation in terrestrial planets , Europlanet Science Congress 2020, online, 21 Sep–9 Oct 2020, EPSC2020-764, https://doi.org/10.5194/epsc2020-764, 2020.

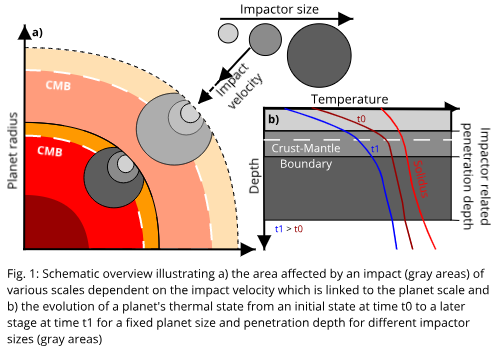

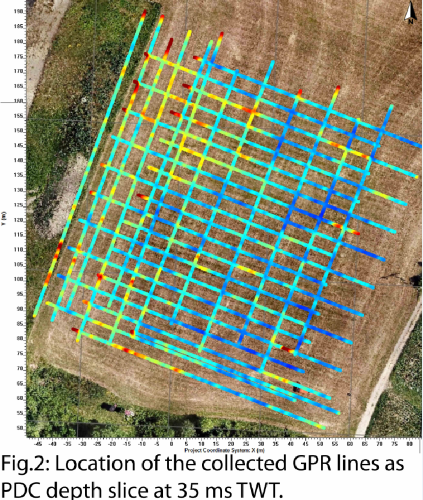

How to cite: Wilk, J. and Wulf, G.: Ground-penetrating radar (GPR) of the Ries crater's ejecta blanket at Aumühle, Europlanet Science Congress 2020, online, 21 Sep–9 Oct 2020, EPSC2020-1120, https://doi.org/10.5194/epsc2020-1120, 2020.

Introduction: The Lockne impact structure, located in central Sweden, is a well-preserved marine-target crater that was formed ~470 million years ago in the epicontinental sea that covered great part of the Baltoscandia [1][2]. The water depth at the time of the impact is interpreted to approximately have been 500 meters, or possibly more [3]. The nearly horizontal target rocks were comprised of, from top to bottom, ~50m of limestone, ~30m of dark, organic rich, shale, and Proterozoic crystalline basement [1]. The Locke structure consists of a concentric 7.5 km wide nested crater, in the basement, surrounded by a 14 km wide outer crater, where most of the sediment material was excavated [2]. Core drilling in the interior of the nested inner crater revealed crater-fill breccias composed mostly by sedimentary material, interfingered with crystalline breccia lens (Tandsbyn breccia) and resurge deposits (Lockne breccia and Loftarsone). Lockne-Målingen crater doublet has been hypothesized to have formed by a rubber-pile “pancake” shaped impactor [4]. This study aims to understand, through numerical simulations, the crater formation based on different asteroid parameters such as density, shape, and velocity.

Methodology: The formation of Lockne is being simulated by iSALE, an extension of the SALE hydrocode developed to model impact crater formation [5,6,7,8]. Current study focuses on iSALE-2D simulations with an axisymmetric approximation of the original impact problem and a resolution of 20, 30 and 60 CPPR (cells per projectile radius), depending on the simulation. The main question to be explored is the influence of the impactor parameters on crater development.

In the 60 CPPR simulations, we consider a four-layer target represented by different equations of estate (EoS): (1) crystalline basement as granite, (2) 30 meters of mudstone as wet tuff, (3) 50 meters of limestone as calcite, and (4) 500 meter of sea water. In this case we set a 600-meter wide massive asteroid traveling at 20km/sec.

For the 30 CPPR simulations the model comprises a three-layer target: (1) crystalline basement, (2) ~80 meters of limestone, and (3) 500 m of sea water. In the first set of 30 CPPR, we consider a massive 600-meter wide asteroid with velocity of 20 km/sec, and also a 7km/sec simulation where, in order to keep the same kinetic energy released by the impact, the asteroid diameter was expanded to 1200 m. To compensate the doubled volume, we set damage value to the maximum of 1, suggesting less cohesive, and more fragmented, material.

The 20 CPPR simulations consider a “pancake” shaped asteroid based on the original and doubled asteroid size. We kept the original volume of the asteroid and calculated the new diameter/height in an approximately 8:1 ratio. For these simulations, we consider the three-layer target (similar to 30 CPPR simulations), asteroid damage set to 1, and impact velocity of 7 km/sec.

Results and Discussion: Cratering processes were observed mostly in 30 CPPR simulations, which have reached up to ~900 seconds. Simulations show a maximum transient crater at approximately 15 seconds, and the ejecta curtain starts to collapse over the water layer around 25-30 seconds, forming a tsunami wave that moves outwards. Some amount of water is kept in the crater interior without being ejected and then, at 52 seconds, the sea water starts to move back into the crater, gradually filling the structure, bringing ejecta sediments and crystalline material. At about 650 seconds the water layer is stable and covering the entire 8km wide structure.

In the 30 CPPR simulations, the higher velocity simulation revealed a pressure peak of ~90GPa at 0.1 seconds (same was observed for 60 CPPR), whereas the lower velocity simulations show a peak of ~50GPa, even with the enlarged projectile. Temperature peaks are also higher for faster impact, being ~8000K for 20km/sec (similar in 60 CPPR) and 1850K for 12km/sec. The amount of kinetic energy on both cases is similar but the velocity itself seems to play an import role in pressure and temperature conditions. If not, these significant differences can be attributed to different asteroid damage values. New simulations, with similar asteroid damage values, are being prepared to better understand the influence of damage on crater formation. Other differences are related to volume of excavated material. Higher speed simulations show a maximum transient crater with 8km in diameter and 2.0km in depth, whereas lower speed impact show a 7 km wide crater with 2km in depth.

The 20 CPPR simulations with a “pancake” shaped asteroid were performed keeping exactly the same parameters as previous 30 CPPR simulations, just changing the asteroid shape. Peak pressure and temperature were lower for spherical asteroids (Table 1), being the difference in temperature more significant than the difference in pressure.

As future work, we intend to perform simulations where the asteroid density is decreased by addition of porosity properties to the material. Also, to perfom different combinations in order to explore the actual role of projectile velocity and damage.

| Peak | Spherical projectile | Ellipsoid projectile |

| Pressure | 45 GPa | 52 GPa |

| Temperature | 1850 K | 11500 K |

Table 1. Peak pressure and temperature for two identical simulations except for the projectile shape. Speed: 7km/sec, Damage=1

References: [1] Lindström et al. (2005) Impact Studies, Springer 357-388 [2] Ormö et al. (2007) Meteoritics & Planet. Sci. 42, 1929-1943 [3] Ormö et al. (2002) JGR, 107, 31-39 [4] Sturkell E. and Ormö J., EPSC abstracts 2020, EPSC2020-956. [5] Melosh H.J. et al. (1992) JGR 97, no. E9, 14735-14759. [6] Ivanov B.A. et al. (1997) Int. J. Impact Eng. 20, 411-430. [7] Collins G. et al. (2004) MAPS 39, 217-231. [8] Wunnemann K. et al. (2006) Icarus 180, 514-527.

Acknowledgements: The authors are grateful to the CSIC financial support for international cooperation: I-LINK project LINKA20203 “Development of a combined capacity of numerical and experimental simulation of cosmic impacts with special focus on effects of marine targets”.

How to cite: De Marchi, L., King, D., Ormö, J., Sturkell, E., and Agrawal, V.: Numerical simulations of Lockne impact crater formation using iSALE-2D, Europlanet Science Congress 2020, online, 21 Sep–9 Oct 2020, EPSC2020-431, https://doi.org/10.5194/epsc2020-431, 2020.

Please decide on your access

Please use the buttons below to download the presentation materials or to visit the external website where the presentation is linked. Regarding the external link, please note that Copernicus Meetings cannot accept any liability for the content and the website you will visit.

Forward to presentation link

You are going to open an external link to the presentation as indicated by the authors. Copernicus Meetings cannot accept any liability for the content and the website you will visit.

We are sorry, but presentations are only available for users who registered for the conference. Thank you.