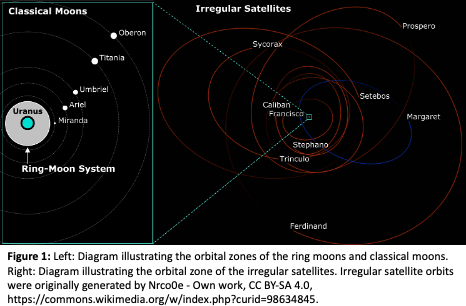

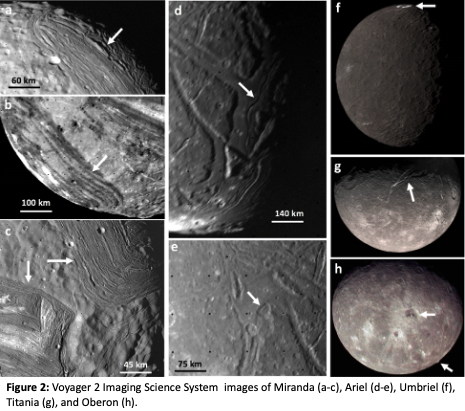

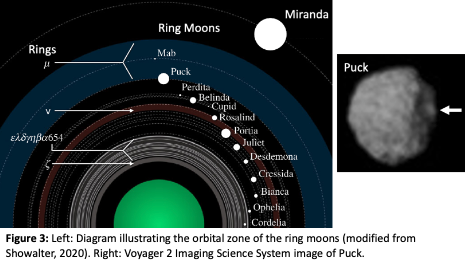

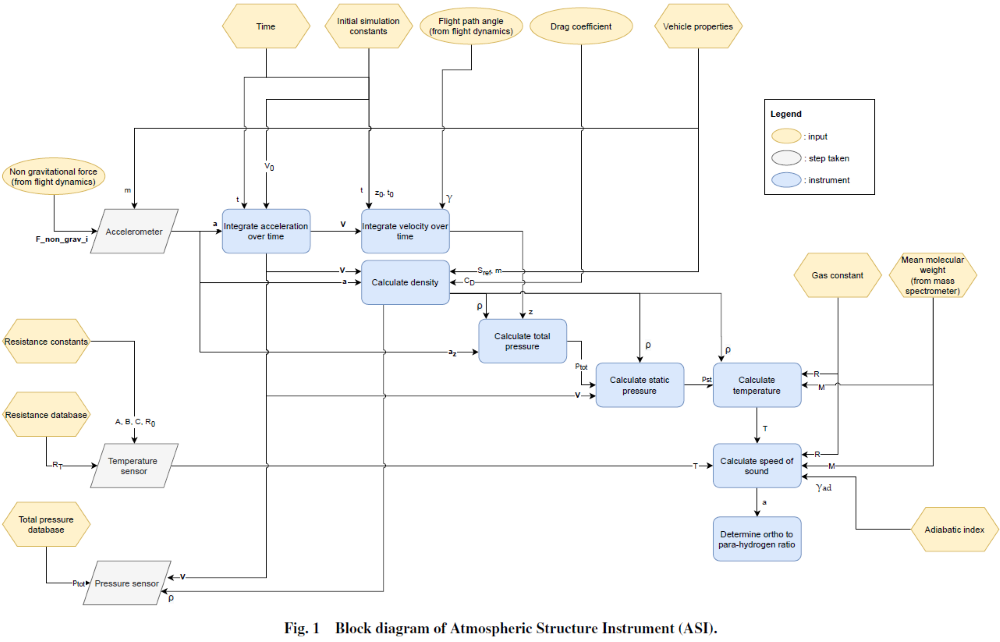

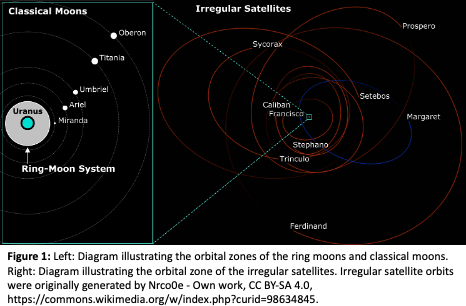

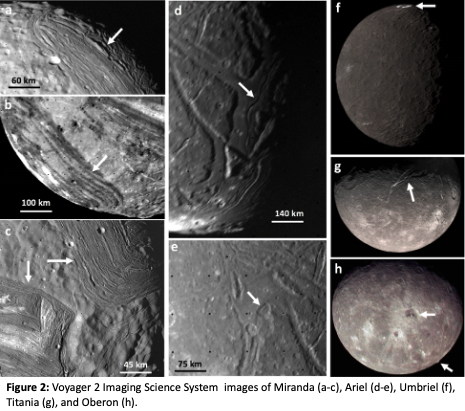

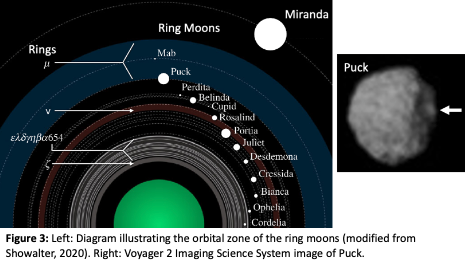

The 27 moons of Uranus (Figure 1) are enigmatic and remain poorly understood. Voyager 2 flew by the Uranus system in 1986, collecting fascinating images of its five largest, tidally-locked ‘classical’ moons (Figure 2), while also discovering a bevy of small moons nestled in its ring system (e.g., [1]) (Figure 3). The surfaces of Uranus’ classical moons Miranda, Ariel, Umbriel, Titania, and Oberon have been modified by endogenic activity, in particular Miranda and Ariel, which exhibit substantial evidence for geologic communication between their interiors and surfaces (e.g., [1-3]) (Figure 2). The available images therefore indicate that these classical moons are candidate ocean worlds, which have, or had, liquid H2O layers beneath their icy exteriors (e.g., [3-5]).

Because the Voyager 2 flyby occurred near Uranus’ southern summer solstice (subsolar latitude ~81°S), the collected images are centered near the south poles of these moons, and their northern hemispheres were largely unobservable. Furthermore, only the classical moons and the largest ring moon Puck (Figure 3) were spatially resolved by Voyager 2. The other nine ring moons Cordelia, Ophelia, Bianca, Cressida, Desdemona, Juliet, Portia, Rosalina, and Belinda were not resolved. Another ring moon, Perdita, was discovered via reanalysis of Voyager 2 data [6], and two more ring moons, Cupid and Mab [7,8], were discovered by space-based telescope observations. All nine known irregular satellites, Francisco, Caliban, Stephano, Trinculo, Sycorax, Margaret, Prospero, Setebos, and Ferdinand, were not detected by Voyager 2 and were discovered later by ground-based observations (e.g., [9-11]).

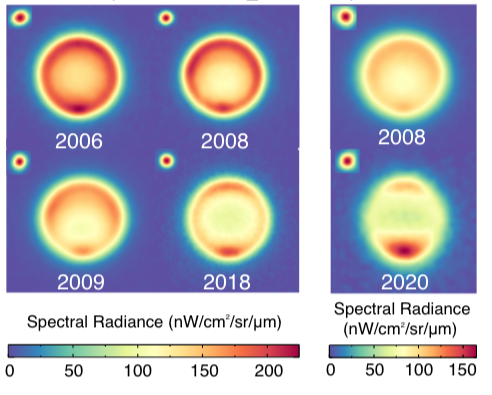

Voyager 2 was not equipped with a near-infrared (NIR) mapping spectrometer, and most of what we know about the compositions of Uranus’ moons has been determined using data collected by ground and space-based telescopes. The surfaces of Uranus’ classical moons are composed of H2O ice mixed with low albedo material that could be rich in organics and silicate minerals (e.g., [12-14]). Carbon dioxide (CO2) has been detected on the classical moons, primarily on their trailing hemispheres, in particular on Ariel [15,16] (Figure 4). Spectrally red material that could be rich in organics has been detected, primarily on the leading hemispheres of these moons (e.g., [17,18]) (Figure 4). Ammonia (NH3) has possibly been detected on the classical moons and may originate from their interiors [18,19]. Although useful, these prior observations are disk-integrated, limiting our ability to constrain the distribution of surface constituents and identify links between volatile species and geologic terrains. Much less is known about the surface compositions of Uranus’ 13 ring moons and nine irregular satellites, which are mostly too faint (Vmag 19.8 - 25.8) for spectroscopic analysis using existing facilities. Spectrophotometric datasets indicate that Uranus’ ring moons have dark surfaces that show hints of H2O ice features [6]. Uranus’ irregular satellites have dark, reddish surfaces (e.g., [20]) but little else is known about their surface compositions, except for Sycorax, which shows hints of H2O ice [21].

An orbiting spacecraft collecting data during close flybys of Uranus’ ring system and classical moons would reveal the surface geologies of these moons, including on their previously unobserved northern hemispheres, determine their surface compositions, and determine whether any of the classical moons are, or were, ocean worlds. Furthermore, an orbiter could spend time looking outward to characterize Uranus’ irregular satellites, providing new insight into these likely captured objects (e.g., Jewitt & Haghighipour 2007). By utilizing a Jupiter gravity assist (2030 - 2034 launch window), a mission could arrive at the Uranian system in the mid 2040’s (∼11 years flight time), using existing chemical propulsion technology [22]. This arrival time frame would allow us to observe these moons’ northern hemispheres. An orbiter making close flybys of the classical moons could search for evidence of ongoing geologic activity and characterize migration of CO2 in response to changes in subsolar heating as the Uranian system transitions into southern spring in 2050.

To determine whether liquid H2O layers are present in the interiors of the classical moons, the highest priority instrument onboard an orbiter would be a magnetometer, which could detect and characterize induced magnetic fields emanating from briny subsurface oceans. Visible (VIS, 0.4 - 0.7 µm) and mid-infrared (MIR, 5 - 250 µm) cameras would also be vital to search for plume activity, hot spots, and other signs of geologic communication between the interiors and surfaces of these moons. A spectrometer (0.4 - 5 µm) would be critical for characterizing volatile species that might result from outgassing of material or recently exposed or emplaced surface deposits. The abundant evidence for geologic activity in the recent past on Ariel and Miranda likely makes them the highest priority targets for any mission that aims to characterize Uranus’ satellites.

References: [1] Smith, B. A. et al. 1986, Science, 233, 43. [2] Schenk, P. M. 1991, JGR: Solid Earth, 96, 1887. [3] Beddingfield, C. B. & Cartwright, R. J. 2020, Icarus, 113687. [4] Hendrix, A. R. et al. 2019, Astrobiology, 19, 1. [5] Cartwright, R.J. et al. 2021. arXiv preprint arXiv:2105.01164. [6] Karkoschka, E. 2001, Icarus, 151, 51. [7] Showalter, M. R. & Lissauer, J. J. 2006, Science, 311, 973. [8] De Pater, I. et al. 2006, Science, 312, 92. [9] Gladman, B. J. et al. 1998, Nature, 392, 897. [10] Kavelaars, J. et al. 2004, Icarus, 169, 474. [11] Sheppard, S. S. et al. 2005, AJ, 129, 518. [12] Cruikshank, D. et al. 1977, AJ, 217, 1006. [13] Clark, R. N. & Lucey, P. G. 1984, JGR: Solid Earth, 89, 6341. [14] Brown, R. H. & Clark, R. N. 1984, Icarus, 58, 288. [15] Grundy, W. et al. 2006, Icarus, 184, 543. [16] Cartwright, R. J. et al. 2015, Icarus, 257, 428. [17] Buratti, B. J. & Mosher, J. A. 1991, Icarus, 90, 1. [18] Cartwright, R. J. et al. 2018, Icarus, 314, 210. [19] Cartwright, R. J. et al. 2020c, ApJL, 898, L22. [20] Maris, M. et al. 2007, A&A, 472, 311. [21] Romon, J. et al. 2001, A&A, 376, 310. [22] Hofstadter, M. et al. 2019, Planetary and Space Science, 177, 104680.