ODAA4

Professional-Amateur collaborations in small bodies, terrestrial and giant planets, exoplanets, and ground-based support of space missions

Convener:

Marc Delcroix

|

Co-conveners:

Glenn Orton,

Veikko Mäkelä,

Ricardo Hueso,

John Rogers,

Florence Libotte

Orals MON-OB5

|

Mon, 08 Sep, 16:30–17:54 (EEST) Room Neptune (rooms 22+23)

Posters MON-POS

|

Attendance Mon, 08 Sep, 18:00–19:30 (EEST) | Display Mon, 08 Sep, 08:30–19:30 Finlandia Hall foyer, F217–224

Hundreds of regular observers are sharing their work providing very valuable data to professional astronomers. This is very valuable at a time when professional astronomers face increasing competition accessing observational resources. Additionally, networks of amateur observers can react at very short notice when triggered by a new event occurring on a solar system object requiring observations, or can contribute to a global observation campaign along with professional telescopes.

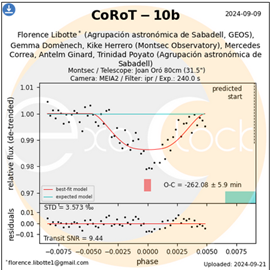

Moreover, some experienced amateur astronomers use advanced methods for analysing their data meeting the requirements of professional researchers, thereby facilitating regular and close collaboration with professionals. Often this leads to publication of results in peer-reviewed scientific journals. Examples include planetary meteorology of Jupiter, Saturn, Neptune or Venus; meteoroid or bolide impacts on Jupiter; asteroid studies, cometary or exoplanet research.

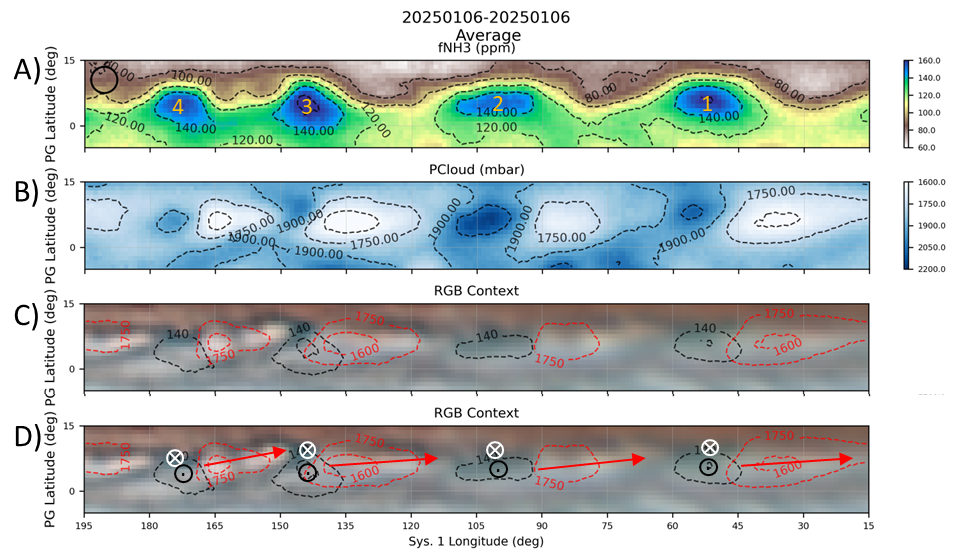

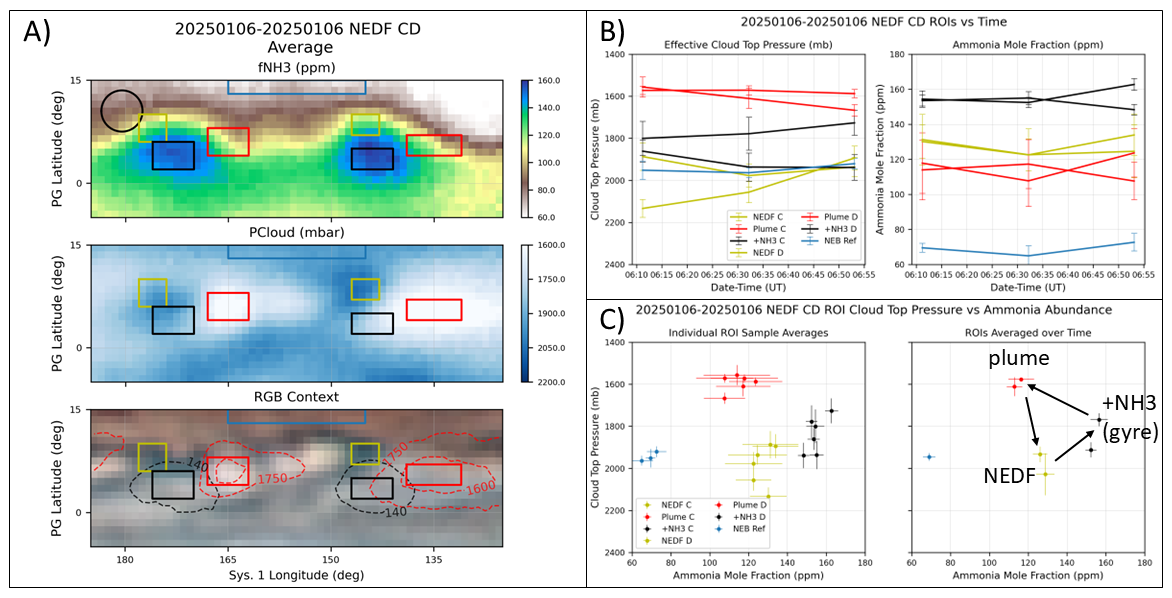

Space missions also sollicitate amateur astronomers support. For example, to understand the atmospheric dynamics of the planet at the time of Juno flybys, NASA collaborates with amateur astronomers observing the Giant Planet. It showcases an exciting opportunity for amateurs to provide an unique dataset that is used to plan the high-resolution observations from JunoCam and that advances our knowledge of the Giant planet Jupiter. Contribution of amateurs range from their own images to Junocam images processing and support on selecting by vote the feature to be observed during the flybys. Other probes like Ariel or Lucy sollicitate amateur astronomers observation to support exoplanets and small bodies science.

This session will showcase results from amateur astronomers, working either by themselves or in collaboration with members of the professional community. In addition, members from both communities will be invited to share their experiences of pro-am partnerships and offer suggestions on how these should evolve in the future.

Session assets

Exoplanets

16:30–16:42

|

EPSC-DPS2025-1685

|

On-site presentation

16:42–16:54

|

EPSC-DPS2025-1682

|

ECP

|

On-site presentation

16:54–17:06

|

EPSC-DPS2025-1826

|

ECP

|

Virtual presentation

Small Bodies

17:06–17:18

|

EPSC-DPS2025-490

|

On-site presentation

17:18–17:30

|

EPSC-DPS2025-1941

|

Virtual presentation

Giant Planets

17:30–17:42

|

EPSC-DPS2025-1174

|

Virtual presentation

17:42–17:54

|

EPSC-DPS2025-1590

|

On-site presentation

Jupiter

F217

|

EPSC-DPS2025-51

|

On-site presentation

Comets

F220

|

EPSC-DPS2025-1222

|

On-site presentation

F221

|

EPSC-DPS2025-160

|

On-site presentation

Exoplanets

F222

|

EPSC-DPS2025-456

|

On-site presentation

F223

|

EPSC-DPS2025-173

|

On-site presentation

Miscellaneous

F224

|

EPSC-DPS2025-604

|

On-site presentation