Multiple terms: term1 term2

red apples

returns results with all terms like:

Fructose levels in red and green apples

Precise match in quotes: "term1 term2"

"red apples"

returns results matching exactly like:

Anthocyanin biosynthesis in red apples

Exclude a term with -: term1 -term2

apples -red

returns results containing apples but not red:

Malic acid in green apples

hits for "" in

Network problems

Server timeout

Invalid search term

Too many requests

Empty search term

SB10

The rapid advancement of observational and modeling techniques has elevated meteor science to one of the primary avenues for investigating the nature and origin of interplanetary matter and its parent bodies. This session aims to serve as a platform for presenting fundamental results and innovative concepts in this field, while also informing the broader planetary science community about the interdisciplinary impact of ongoing and future research efforts.

Session assets

Hydrated, carbonaceous asteroids constitute the majority of the main‑belt [1], whereas carbonaceous chondrites form just ≈4% of the >83,000 meteorites in collections [2]. Additionally, recent meteoroid transfer models from young asteroid families predict >50% of the meteoroid impacts at the top of the atmosphere should be carbonaceous in composition, a mismatch often ascribed—to their inherent material fragility [2,3].

Methods

To test whether Earth’s atmosphere drives the mismatch between the predicted carbonaceous meteoroid flux and the recovered carbonaceous meteorite flux, we compared the orbital distributions of a debiased sporadic asteroidal impact population against those of meteorite‑dropping fireballs. We assembled 7,982 top‑of‑atmosphere sporadic impacts (≥ 10 g) from five global networks (EDMOND, CAMS, GMN, EFN, FRIPON), spanning 19 camera systems across 39 countries. Meteor showers were removed using the Valsecchi DN < 0.1 criterion (≤ 5 % false positives) and cometary contributions (TJ < 2 for LPCs; Tancredi criterion for JFCs with TJ>2), isolating the asteroidal sporadic component. To mitigate velocity‑dependent detection bias for faint meteors, each network was debiased by imposing minimum mass cutoffs. We then identified 540 candidate meteorite‑dropping events (≥ 1 g) from FRIPON, EFN, and GFO using α–β dynamic criteria and photometric mass estimates. Finally, we constructed 10×10 binned, two‑dimensional histograms in orbital element spaces—(a,e), (a,i), (i,q), (i,Q)—and performed χ² tests of independence on each bin (α = 0.0455 for 2 σ, α = 0.0027 for 3 σ) to locate statistically significant discrepancies between the total cm-m impactor flux and the meteorite-dropping subpopulation. Relative density differences, Δ = (f_sub – f_ref)/f_ref × 100 %, were mapped to highlight over‑ and under‑abundant orbital regions between the impactor and fall populations

Results

- Perihelion filter dominates – Objects that have present or past perihelia q << 1 au are up to 10x over-represented in the fall sample relative to all impacts (Fig. 1)

- More high-velocity survivors than expected – there are more meteorite falls at entry speeds > 20 km s−1 despite higher ablation losses, some survival bias in space already removing the weaker meteoroids.

- Atmospheric removal – For impactors ≥ 1 kg, only roughly 30–50% deliver ≥ 50 g fragments to the ground.

- Tidal debris appears fragile – tidally disrupted NEO-cluster fragments contribute 0.2 % of the falls vs 0.4 % to all impactors, i.e., are 2x weaker according to these results. However, further work is necessary to confirm this, as this assumes that NEA clustering can be directly tied to meteor and fireball data despite the lack of statistically significant evidence within these observations alone.

Fig. 1 Comparison of orbital distributions for all impactors versus those that produce meteorites. Each panel shows a heatmap of the percentage difference between the normalized density of impacts ≥ 10 g at the top of the atmosphere and the subset of those that yield meteorite falls ≥ 1 g, binned by orbital parameters. Reds mark regions where meteorite‑dropping events are over‑represented relative to the overall impactor flux, while blues show under‑representation. Bins outlined in bold indicate differences significant at the 3σ level (chi‑square test); unoutlined bins meet the 2σ threshold. The overlaid curves trace the expected Kozai–Lidov resonant exchange between inclination and eccentricity for a semi‑major axis of 2.5 au, illustrating why an excess of meteorite drops appears at high inclinations when perihelion distances approach ~ 1 au.

Discussion

Our findings point to a two‑step selection process—first in interplanetary space and then in Earth’s atmosphere—that reshapes which meteoroids become meteorites and explains the low fraction of carbonaceous falls [4]. First, objects whose orbits currently dip well inside 1 au, or have done so in the recent past, yield up to an order of magnitude more recovered meteorites than their abundance in the overall sporadic flux would predict [4]. Repeated perihelion passages subject fragile, volatile‑rich material to intense thermal cycles, driving micro‑cracking and mass loss that effectively removes the weakest fragments and leaves behind a cohort of heat‑hardened, mechanically robust stones. Second, these survivors—which characteristically enter at higher speeds (> 20 km/s), a regime normally more hostile to meteorite survival—nonetheless endure atmospheric passage more often than slower, less cohesive bodies, demonstrating that intrinsic strength gained from thermal processing outweighs the disadvantage of increased ablation [4]. Even so, once past the thermal fragmentation filter, only about 30-50% of kilogram‑scale meteoroids survive to deposit substantial fragments on the ground (see Supplementary Figure 9 in [4]), confirming that atmospheric breakup remains a significant sieve.

Together, the combined action of solar heating and atmospheric entry preferentially delivers low‑porosity, thermally resilient carbonaceous fragments that have avoided—or survived—severe thermal fatigue. This dual filtering mechanism naturally accounts for the anomalously short cosmic‑ray exposure ages of CI and CM chondrites [3,4] and their pronounced scarcity among collected meteorites [2,3].

References: [1] DeMeo, F. E. and B. Carry. (2014) Nature 505:629–634. [2] Brož, M., et al. (2024) Astronomy & Astrophysics 689:A183. [3] Scherer, P. and L. Schultz. (2000) Meteoritics & Planetary Science 35.1: 145-153. [4] Shober P.M. et al. (2025) Nature Astronomy 14:1-4

How to cite: Shober, P., Devillepoix, H. A. R., Vaubaillon, J., Anghel, S., Deam, S. E., Sansom, E. K., Colas, F., Zanda, B., Vernazza, P., and Bland, P.: Perihelion history and atmospheric disruption: The Primary Culprits of the Missing Carbonaceous Chondrites , EPSC-DPS Joint Meeting 2025, Helsinki, Finland, 7–13 Sep 2025, EPSC-DPS2025-936, https://doi.org/10.5194/epsc-dps2025-936, 2025.

Meteoroid impacts pose a critical threat to spacecraft. Natural objects as small as sub-millimeter ( >0.2 mm) upon impact, can deliver enough kinetic energy to damage or disable satellites[1]. Impact damage is governed by the meteoroid’s velocity, mass and bulk density as given by the ballistic limit equations [2][3]. Slow sporadic meteoroids (velocity < 20 km/s) dominate the meteoroid flux on Earth, but are very difficult to observe by both radar and optical methods, as they produce little ionization and light. Recent work shows that approximately 16% of these slow meteoroids are iron-rich [4], making them especially important to study as their higher bulk density will result in higher impact hazard for satellites in orbit.

In this work, we observe slow and small sporadic meteoroids using high-sensitivity Electron Multiplying CCD (EMCCD) video cameras. These EMCCDs, have a limiting meteor sensitivity of magnitude +8, 50 m/pixel spatial resolution at 100 km, and operate at 32 frames per second (FPS). To complement these measurements we fuse EMCCD data with high resolution imagery from the Canadian Automated Meteor Observatory’s (CAMO) mirror tracking system. CAMO achieves a spatial resolution of 6 m/pixel at 100 km and operates at 100 FPS with limiting detection sensitivity of +7. This provides high-cadence and precision observations of fragmentation and morphology. When merged with higher sensitivity EMCCD data (which captures the onset of ablation earlier) these measurements provide are critical constraints for modelling meteoroid structure.

Our study is based on the analysis of 100 slow sporadic meteors for which we have simultaneous CAMO and EMCCD data. As shown in Fig. 1 our data clearly shows two separate populations of meteoroids : (a) porous cometary particles that fragment and decelerate rapidly at high altitudes, and (b) dense, iron-rich or stony asteroidal meteoroids with minimal deceleration. These findings support past results [5].

Fig. 1. 100 slow meteoroids jointly recorded by EMCCD and CAMO video systems and their total trail length as a function of the energy required to be intercepted through atmospheric molecular collisions to begin erosive fragmentation and F-parameter. The F-parameter is a normalized measure of the location of the peak brightness along the trail with 0 indicating peak at the start and 1 peak brightness at the end of the trail. These two populations are denoted with (a) and (b). Following the work in [4] iron meteoroid candidates are those that have F < 0.31, Trail Length < 11 km and erosion Energy per unit cross section > 4 MJ/m.

To robustly infer the physical properties of these meteoroids based on our observations, we develop a novel method using Dynamic Nested Sampling [6]. This Bayesian inference technique, implemented via the dynesty Python package [7], is specifically designed to handle high-dimensional, degenerate, and multimodal parameter spaces. We use the Borovička et al. (2007) [8] meteoroid ablation and fragmentation to provide model fits to measured brightness and deceleration of meteors. This model assumes meteoroids fragment by continuous ejection of micrometer-sized grains. In combination with Dynamic Nested Sampling, we are able to define statistically significant solutions with credible intervals (CIs) for all the meteoroid physical characteristics. We define a custom log-likelihood function that jointly incorporates measurements of both luminosity and meteoroid dynamics. Unlike traditional forward-modeling approaches [8][9], which are challenged to produce uncertainty estimation and solution degeneracy, our method allows rigorous quantification of posterior distributions, capturing model degeneracies, and assessment of the uniqueness of retrieved solutions.

Our work provides the first probabilistic framework to extract meteoroid mass, bulk density, and fragmentation properties from atmospheric observations of meteoroids with quantified uncertainties. These results offer valuable inputs for space environment models like NASA’s MEM [10] and ESA’s IMEM [11] helping safeguard satellites from an often overlooked impact threat.

References:

[1] Moorhead, A. V. et al. (2019). Planetary and Space Science, 165, 208–218.

[2] Christiansen, E. L. (2001). NASA TP-2001-210788.

[3] Moorhead, A. V. et al. (2020). NASA/TM–20205011017.

[4] Mills, T. M. et al. (2021). Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society, 506(4), 6012–6024.

[5] Vida, D., Brown, P. G., & Campbell-Brown, M. (2018). Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society, 479(4), 4307–4319.

[6] Higson, E., Handley, W., Hobson, M., & Lasenby, A. (2019). Statistics and Computing, 29, 891–913.

[7] Speagle, J. S. (2020). Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society, 493(3), 3132–3158.

[8] Borovička, J. et al. (2007). Astronomy & Astrophysics, 473(2), 661–672.

[9] Buccongello, N., Brown, P. G., Vida, D., & Pinhas, A. (2024). Icarus, 410, 115907.

[10] Moorhead, A. V. (2020) NASA/TM-2020-220555.

[11] Soja, R. H., et al. (2019) Astronomy & Astrophysics, 628 (2019): A109.

How to cite: Vovk, M., Brown, P., and Vida, D.: Characterizing the Population of Small & Slow Meteoroids: New Physical Characterization Method for Satellite Risk Assessment, EPSC-DPS Joint Meeting 2025, Helsinki, Finland, 7–13 Sep 2025, EPSC-DPS2025-66, https://doi.org/10.5194/epsc-dps2025-66, 2025.

The International Astronomical Union (IAU) currently lists around 1200 meteor showers, raising questions about their reality given our current understanding of the Solar System, and the need for a comprehensive re-evaluation. This ongoing study aims to assess the feasibility of these showers originating from known near-Earth comets and asteroids, considering their orbital dynamics, dust production capabilities and residence times. Our study focuses on several key aspects:

- Impact Configurations from Near-Earth Comets: We estimate the number of possible meteor shower orbits produced by near-Earth comets, taking into account the Kozai and precession cycles.

- Active Asteroids as Parent Bodies: We examine active asteroids as potential sources of meteor showers, considering their quantity, dust production rates and lifetime expectancies.

- Near-Earth Asteroids Contribution: We explore the role of near-Earth asteroids in generating meteor showers.

By integrating these factors, we aim to determine if the current near-Earth environment can indeed support the existence of 1200 meteor showers. This work-in-progress seeks to align our understanding of meteor shower origins with the observed data. The findings will contribute to our broader comprehension of the dynamics and interactions within the near-Earth environment.

How to cite: Ashimbekova, A. and Vaubaillon, J.: Re-evaluating the Reality of 1200 Meteor Showers in the International Astronomical Union List and Their Implications for the Near-Earth Environment, EPSC-DPS Joint Meeting 2025, Helsinki, Finland, 7–13 Sep 2025, EPSC-DPS2025-1498, https://doi.org/10.5194/epsc-dps2025-1498, 2025.

Climate change, driven by increased greenhouse gas concentrations, not only warming the troposphere (∼0–10 km) but also cooling and contracting the atmosphere above, including the stratosphere (∼10–50 km), mesosphere (∼50–85 km), and thermosphere (∼85–500+ km) [1–3]. This contraction is measurable and has been confirmed by multiple independent datasets and models over the past two decades. In particular, meteor radars, which routinely detect the ablation of small impact micrometeoroids at altitudes between 80 and 100 km, have shown that the peak ablation altitude is decreasing at rates ranging from ~200 to 800 m per decade [4–8]. This observed lowering is consistent with expectations from cooling-induced density changes at fixed altitudes. Although the implications of these changes for satellite drag and orbital debris lifetimes are starting to be explored in detail [9,10], little attention has been paid to their possible influence on larger meteoroids that penetrate deeper into the atmosphere and survive as meteorites.

In this study, we investigate whether ongoing climate-driven changes in atmospheric density can significantly affect the atmospheric trajectory and survivability of meteorite dropping fireballs, focusing on the century-scale timescale. To do this, we simulate the atmospheric entry of the Winchcombe meteorite fall, one of the best documented carbonaceous chondrite falls to date, under both atmospheric conditions of 2021 and those projected for the year 2100, using the output of the climate model from the WACCM-X (Whole Atmosphere Community Climate Model - Extended) [11]. The model assumes a moderate emissions scenario (SSP2-4.5) [12], and the density trends are extracted from simulations accounting for solar and geomagnetic activity variations [13].

Winchcombe represents an ideal test case. It was a slow low-altitude fireball (entry velocity: 13.9 km/s) with minimal atmospheric deceleration below 40 km, and produced a carbonaceous CM2 chondrite [14]. Its low strength (onset of fragmentation at ~0.07 MPa) and unusually low peak dynamic pressure (~0.6 MPa) make it highly sensitive to changes in atmospheric density. We modeled its entry using a semi-empirical fragmentation and erosion model [15–17], informed by manual identification of fragmentation points and limited by deceleration and photometry data. The simulations were repeated under a projected 2100 atmospheric density profile, obtained by applying regression-derived trends from WACCM-X output to the location and season of the Winchcombe fall. See Figure 1.

The comparison between the 2021 and 2100 simulations shows only modest differences in trajectory, light curve, and survivability. The luminous trajectory begins 3 km lower in the 2100 case for a typical +3 magnitude detection threshold. The first fragmentation occurs 820 m lower and the catastrophic fragmentation that produces most of the surviving fragments occurs 300 m lower. However, the final luminous point is actually 190 m higher in 2100 because of slightly faster deceleration in the denser lower stratosphere. The peak brightness remains virtually unchanged, although the fireball is ~0.5 mag fainter at altitudes above 120 km, due to lower densities and reduced drag in the mesosphere. The final surviving mass is reduced by just 0.13 g, or 0.037%, from an initial ~13 kg meteoroid. These variations are small compared to daily and seasonal variations in density [18], and are far below the uncertainties in most meteorite recovery campaigns.

Figure 1. Dynamic pressure vs. altitude for the Winchcombe fireball (blue) and its 2100 climate change simulation (red), with eleven fragmentation points marked (crosses). The right panel shows their pressure differences (black).

Acknowledgements

EP-A acknowledges financial support from the LUMIO project funded by the Agenzia Spaziale Italiana (2024-6-HH.0). DV was supported in part by the NASA Meteoroid Environment Office under cooperative agreement 80NSSC24M0060. IC was supported by a Natural Environment Research Council (NERC) Independent Research Fellowship (NE/R015651/1). EF acknowledges the funding received by the Grant DeepCFD (Project No. PID2022-137899OB-I00) funded by MICIU/AEI/10.13039/501100011033 and by ERDF, EU.

References

[1] Roble, R. G., & Dickinson, R. E. (1989). Geophysical Research Letters, 16(12), 1441–1444.

[2] Cnossen, I., Emmert, J. T., Garcia, R. R., Elias, A. G., Mlynczak, M. G., & Zhang, S.-R. (2024). Advances in Space Research, 74(11), 5991–6011.

[3] Emmert, J. T. (2015). Journal of Geophysical Research: Space Physics, 120(4), 2940–2950.

[4] Clemesha, B., & Batista, P. (2006). Journal of Atmospheric and Solar-Terrestrial Physics, 68(17), 1934–1939.

[5] Jacobi, C. (2014). Advances in Radio Science, 12, 161–165.

[6] Lima, L. M., Araújo, L. R., Alves, E. O., Batista, P. P., & Clemesha, B. R. (2015). Journal of Atmospheric and Solar-Terrestrial Physics, 133, 139–144.

[7] Dawkins, E. C. M., Stober, G., Janches, D., et al. (2023). Geophysical Research Letters, 50(2).

[8] Venkat Ratnam, M., Teja, A., Pramitha, M., et al. (2024). Advances in Space Research.

[9] Brown, M. K., Lewis, H. G., Kavanagh, A. J., & Cnossen, I. (2021). Journal of Geophysical Research: Atmospheres, 126(8).

[10] Brown, M., Lewis, H., Kavanagh, A., Cnossen, I., & Elvidge, S. (2024). Journal of Geophysical Research: Space Physics.

[11] Cnossen, I. (2022). Geophysical Research Letters, 49(19).

[12] O’Neill, B. C., Tebaldi, C., van Vuuren, D. P., et al. (2016). Geoscientific Model Development, 9(9), 3461–3482.

[13] Matthes, K., Funke, B., Andersson, M. E., et al. (2017). Geoscientific Model Development, 10(6), 2247–2302.

[14] McMullan, S., Vida, D., Devillepoix, H. A. R., et al. (2024). Meteoritics & Planetary Science, 59(5), 927–947.

[15] Borovička, J., Tóth, J., Igaz, A., et al. (2013). Meteoritics & Planetary Science, 48(10), 1757–1779.

[16] Borovička, J., Spurný, P., & Shrbený, L. (2020). The Astronomical Journal, 160(1), 42.

[17] Vida, D., Brown, P. G., Devillepoix, H. A. R., et al. (2023). Nature Astronomy, 7, 318–329.

[18] Vida, D., Brown, P. G., Campbell-Brown, M., et al. (2021). Icarus, 354, 114097.

How to cite: Peña-Asensio, E., Vida, D., Cnossen, I., and Ferrer, E.: Effect of climate change on meteorite dropping fireballs, EPSC-DPS Joint Meeting 2025, Helsinki, Finland, 7–13 Sep 2025, EPSC-DPS2025-594, https://doi.org/10.5194/epsc-dps2025-594, 2025.

Observing meteors through a combination of spectral and multi-station trajectory measurements presents unique opportunities for mapping the compositional diversity of small Solar System bodies from various orbital sources. This research is conducted by the AMOS (All-sky Meteor Orbit System) network, providing global coverage of meteors and their emission spectra from 17 stations in Slovakia, the Canary Islands, Chile, Hawaii, Australia, and South Africa. Recent advancements from our plasma wind tunnel ablation experiments helped characterize the diagnostic spectral features of various meteorite types, enabling more efficient identification of atypical meteoroid populations not commonly recognized by meteor surveys.

We first review the emission spectral properties of individual achondrite types obtained during meteorite ablation experiments, which serve as guides for meteor spectra interpretation (Matlovič et al., 2024). Then, we present the results of our search for achondritic meteoroid impactors captured by the AMOS stations over Hawaii and the Nullarbor Plain in collaboration with the Desert Fireball Network (Devillepoix et al., 2022).

Two achondrites – likely an aubrite and an eucrite – were identified, exhibiting distinct spectral and ablation properties. We discuss their emission spectra, dynamical properties including orbital integrations studying their source and evolution, and physical properties derived from light curve, deceleration, and fragmentation modeling.

For the aubrite, spectral analysis revealed strong emissions of Mg, Si, Mn, Ca, Ti, and Li, along with a notably low Fe content, consistent with an enstatite-enriched composition. The second achondrite displayed notably higher Fe content and even stronger intensities of refractory elements (Ca, Al and Ti), consistent with compositions similar to howardites or eucrites not significantly depleted in magnesium.

Dynamical analysis placed the eucrite on an asteroidal orbit with increased eccentricity (a = 2.09 au, e = 0.78, i = 3.7°), while the aubrite originated from a short-period orbit (a = 1.16 au, e = 0.31, i = 2.3°). Orbital integrations indicate relatively stable orbits for both bodies over the past 500 years. Fitting light curves and deceleration profiles proved challenging using standard ablation and fragmentation models. Preliminary results from an individual approach accounting for differential ablation are consistent with the assumed compact differentiated meteoroid material, indicating bulk densities > 3000 kg/m3.

Characterizing atypical meteoroid populations improves our understanding of the material distribution, diversity, and evolution of small Solar System bodies. The presented results support the future identification of achondritic meteoroids by meteor surveys through spectral and physical properties. Accurate prediction of meteoroid composition also proves crucial for modeling and locating meteorite impacts, as demonstrated by the Ribbeck aubrite fall in 2024 (Spurný et al., 2024).

References

Devillepoix H., Tóth J., Matlovič P., Cupák M., Towner M., Sansom E., Kornoš L., Paulech T., Zigo P. (2022). A Meteor Spectroscopic Survey in the Nullarbor, Research Notes of the AAS, 6 (7), 144

Matlovič P., Pisarčíková A., Pazderová V., Loehle S., Tóth J., Ferrière L., Čermák P., Leiser D., Vaubaillon J., Ravichandran R. (2024). Spectral properties of ablating meteorite samples for improved meteoroid composition diagnostics, Astronomy & Astrophysics, 689, A323, 19 pp.

Spurný P., Borovička J., Shrbený, L., Hankey M., Neubert R. (2024). Atmospheric entry and fragmentation of the small asteroid 2024 BX1: Bolide trajectory, orbit, dynamics, light curve, and spectrum, Astronomy & Astrophysics, 686, A67, 8 pp.

How to cite: Matlovič, P., Pisarčíková, A., Pazderová, V., Devillepoix, H., Hlobik, F., Vörös, T., Paprskárová, M., and Tóth, J.: Characterization of achondritic meteoroid impactors: spectra, dynamics and ablation properties, EPSC-DPS Joint Meeting 2025, Helsinki, Finland, 7–13 Sep 2025, EPSC-DPS2025-1313, https://doi.org/10.5194/epsc-dps2025-1313, 2025.

Small asteroids ranging from 1 − 20 meters in size impact the Earth 35 − 40 times per year (Brown et al. 2002; Bland and Artemieva 2006), often appearing as spectacular fireballs in the atmosphere. The largest of these objects can have kinetic energies equivalent to hundreds of kilotons of TNT, posing a hazard if they impact populated areas. As most recovered meteorites originate from 1 − 20 meter-size asteroids (Borovička 2015), this population in particular presents a unique opportunity to link together data from fireball, telescopic and meteorite observations. The properties of these small asteroids have to date been poorly characterized at a population level, as they are often at the detection limit of telescopic near-Earth object (NEO) surveys while also being relatively rare as Earth impactors. However, the amount of data on this population has grown significantly in recent years. In 2022, the US Space Force publicly released decades of previously classified fireball data from US Government (USG) satellite sensors, including light curves of intensity over time1. This tranche of over one thousand recorded fireballs represents the most comprehensive dataset of meter-size and larger impactors to date.

In Chow and Brown (2025) we undertook the first population-level study characterizing the orbital properties of decameter-size Earth impactors with the new USG sensor data. We analyzed the dynamical origins of decameter-size impactors and NEOs, and evaluated possible explanations for the order-of-magnitude “decameter gap" between the observed impact rate from fireball data and the inferred impact rate from NEO models based on telescopic surveys. Here we present a companion study to our previous paper that characterizes the physical and material properties of these decameter-size impactors using the USG sensor light curves.

Previous studies using light curve data to analyze the physical properties of these small asteroids have generally proceeded by first generating a synthetic light curve by simulating the asteroid’s ablation and fragmentation in the atmosphere and then manually fitting the synthetic light curve to observations by adjusting various model parameters (e.g. Wheeler et al. 2017; Borovička et al. 2020; McFadden et al. 2024). However, this method is slow, labour-intensive, subject to parameter degeneracy and does not quantify uncertainty in the inferred model parameters. Previous attempts to develop automated approaches for ablation modeling using genetic algorithms (Tárano et al. 2019; Henych et al. 2023) have seen only limited success for a small number of fireballs and require an initial manual solution to be found first.

Motivated by the recent release of USG sensor data, we thus develop a novel Bayesian inference method that uses dynamic nested sampling (Skilling 2004, 2006; Higson et al. 2019) in conjunction with the semi-empirical fragmentation model of Borovička et al. (2013) that can probabilistically characterize the physical and material properties of Earth impactors from their light curves. Crucially, our nested sampling-based method allows for robust quantification of parameter uncertainty for the first time by estimating posterior distributions using a Bayesian framework. We first validate our method by applying it to several USG-recorded fireball events for which detailed light curve modeling has previously been conducted using independent ground-based observations and demonstrating that our results are consistent with previous estimates based on manual fitting. We then use our method to model the light curves of 13 decameter-size impactors we previously identified in Chow and Brown (2025), ultimately drawing population-level inferences about their physical properties such as mass and material strength for the first time.

As an example of our procedure, the above figure shows the resulting fit for one of the 13 decameter impactors we analyze, the 1994 February 1 Marshall Islands fireball. On the left, the USG-sensor recorded fireball light curve is plotted in red, while the 1σ, 2σ and 3σ uncertainties of the fit light curve of intensity versus height obtained with nested sampling are shown by the black shaded regions. The maximum log-likelihood solution is plotted as the blue line, while the detection limit of USG sensors is marked by the vertical red line. On the right, the marginal 2D nested sampling posterior distributions of dynamic pressure against mass released at each fragmentation point and at peak dynamic pressure are shown. In this presentation we will summarize the broad results of applying this procedure to all 13 decameter impactors and quantifying their relative strength.

1jpl.nasa.gov/news/us-space-force-releases-decades-of-bolide-data-to-nasa-for-planetary-defense-studies/

References:

-

Bland, P.A., & Artemieva, N.A.. 2006, Meteoritics & Planetary Science, 41 (4): 607–31. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1945-5100.2006.tb00485.x

-

Borovička, J. 2015, Proceedings of the International Astronomical Union, 10 (S318): 80–85. https://doi.org/10.1017/S174392131500873X

-

Borovička, J., Spurný, P., & Shrbený, L. 2020, The Astronomical Journal, 160 (1): 42. https://doi.org/10.3847/1538-3881/ab9608

-

Borovička, J., Tóth, J., Igaz, A., et al. 2013, Meteoritics & Planetary Science, 48 (10): 1757–79. https://doi.org/10.1111/maps.12078

-

Brown, P., Spalding, R.E., ReVelle, D.O., Tagliaferri, E., & Worden, S.P. 2002, Nature, 420 (6913): 294–96. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature01238

-

Chow, I., and Brown, P.G. 2025, Icarus, 429 (March): 116444. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.icarus.2024.116444

-

Henych, T., Borovička, J., & Spurný, P. 2023, Astronomy & Astrophysics, 671 (March): A23. https://doi.org/10.1051/0004-6361/202245023

-

Higson, E., Handley, W., Hobson, M., & Lasenby, A. 2019, Statistics and Computing, 29 (5): 891–913. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11222-018-9844-0

-

McFadden, L., Brown, P.G., & Vida, D. 2024, Icarus, 422 (November): 116250. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.icarus.2024.116250

-

Skilling, J. 2004, in AIP Conference Proceedings, 735: 395–405. Garching (Germany): AIP. https://doi.org/10.1063/1.1835238

-

Skilling, J. 2006, Bayesian Analysis, 1 (4): 833–59. https://doi.org/10.1214/06-BA127

-

Tárano, A.M., Wheeler, L.F., Close, S., & Mathias, D.L. 2019, Icarus, 329 (September): 270–81. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.icarus.2019.04.002

-

Wheeler, L.F., Register, P.J., & Mathias, D.L. 2017, Icarus, 295 (October): 149–69. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.icarus.2017.02.011

How to cite: Chow, I. and Brown, P.: Characterizing Physical and Material Properties of Decameter-Size Earth Impactors, EPSC-DPS Joint Meeting 2025, Helsinki, Finland, 7–13 Sep 2025, EPSC-DPS2025-971, https://doi.org/10.5194/epsc-dps2025-971, 2025.

An update is given reviewing asteroid, meteor, and meteorite-type links [1]. As of April 2025, 81 fireballs have been observed from which a meteorite was recovered. These fireballs record the meteoroid's orbit at the time of entering Earth's atmosphere. The number of observed falls has become sufficient to see that different meteorite types arrive on different orbits. Those show that our meteorites do not predominantly originate from a broad sampling of material from across the entire asteroid belt. Instead, the meteorites delivered to Earth are dominated by debris from the largest collisions among asteroids in the past 100 Ma. Collisions that also created km- and sub-km sized debris recognized as clusters in asteroid families. Following a collision, meter-sized meteoroids initially move more or less along the target asteroid orbit as does larger debris. Over time, Yarkovsky forces increase or decrease the semi-major axis until the orbit reaches one of the resonances, which takes about a million years. In resonance, the orbits quickly become eccentric with the perihelion distance moving in and the aphelion distance moving out. When the perihelion approaches Earth orbit, close encounters with Earth can lift the orbit out of the resonance, lower the semi-major axis and spread the inclination of the orbit over time. It can then still take a long time before meteoroids impact the small Earth. All this time, meteoroids smaller than 2-m in diameter are exposed to cosmic rays and built up cosmogenic nuclei that define the cosmic ray exposure (CRE) age. While in Earth-crossing orbits, CM chondrite meteoroids tend to fragment, but other meteoroids do not. Those have CRE ages that still correspond to the dynamical age of their young asteroid family source. In particular, 12 H chondrites have now been traced to three collision events in the Koronis family, at ~6, 11-14 and ~83 Ma, likely corresponding to the Karin, Koronis_2 and Koronis_3 clusters in that asteroid family. Most large km-sized Near Earth Asteroids (NEA) that are H-chondrite like do not. Those arrive at Earth via the 3:1 resonance from a source at high inclination in the Central Main Belt. Some H chondrites do too, four having a ~6 Ma CRE age that are possibly from the Nele (= Iannini) family. In addition, there is a source of H chondrites in the Inner Main Belt that have a ~35 Ma CRE age. These are likely from the Massalia family, which has a ~40 Ma cluster. All L chondrites observed to date appear to originate from the Inner Main Belt, likely from the Hertha (= Nysa) family. This is also the likely source of the larger km-sized L chondrite NEA, which arrive to Earth via the closer 3:1 resonance, rather than the nu-6 resonance from where most L chondrites are delivered. Most LL chondrites arrive from the Flora family in the Inner Main Belt (both small and large), but the meteorite Benesov likely arrived from the Eunomia family in the Central Main Belt. Unlike their larger cousins, most HED meteorites likely originated at asteroid Vesta, not the Vesta family. Possible source regions of other meteorite types will be discussed also. Based on these results, the meteorite type of a recent fall of a CK carbonaceous chondrites was anticipated because the observed orbit resembled that expected for meteorites delivered from the Eos family.

[1] Jenniskens P., Devillepoix H. A. R., 2025. Review of asteroid, meteor, and meteorite-type links. MAPS 60, 928-973.

How to cite: Jenniskens, P.: Origin of meteorites in the asteroid belt from meteor observations, EPSC-DPS Joint Meeting 2025, Helsinki, Finland, 7–13 Sep 2025, EPSC-DPS2025-146, https://doi.org/10.5194/epsc-dps2025-146, 2025.

Please decide on your access

Please use the buttons below to download the supplementary material or to visit the external website where the presentation is linked. Regarding the external link, please note that Copernicus Meetings cannot accept any liability for the content and the website you will visit.

Forward to presentation link

You are going to open an external link to the presentation as indicated by the authors. Copernicus Meetings cannot accept any liability for the content and the website you will visit.

We are sorry, but presentations are only available for users who registered for the conference. Thank you.

Introduction

Classifying meteoroids based on their physical properties is important for understanding their origins, how they evolve, and what parent bodies they may be linked to. Current classification methods typically rely on simplified physical models like single-body ablation theory or use only a small number of observable characteristics. A commonly used approach is the Kb parameter, which estimates a meteoroid’s material strength based on how it penetrates the atmosphere. But using Kb requires several derived quantities and depends on assumptions about the meteoroid’s structure and behavior. This limits how broadly and objectively the method can be applied, especially when dealing with the large datasets produced by modern automated meteor camera networks.

More advanced fragmentation models can provide better insights, but they’re computationally intensive and have only been applied to relatively small datasets, typically just a few dozen meteors at a time. As these networks continue to grow, we need more scalable and objective methods that rely only on what we can directly observe.

Here, we’re developing a machine learning approach to classify meteoroids based purely on observed characteristics. We use 13 features that can be consistently measured from low-light video cameras, such as energy received before ablation, atmospheric density, and trail length. These inputs are analyzed using dimensionality reduction and clustering to find natural groupings in the data. The goal is to create a reliable, scalable way to classify meteoroids that can keep up with the size and complexity of current and future meteor datasets.

Methods

This project uses data collected in 2023 from two low-light meteor camera networks: the Croatian Meteor Network (CMN) and the Lowell Observatory Cameras for All-sky Meteor Surveillance (LOCAMS). The CMN network features cameras with 16mm lenses, allowing for fainter meteor detections and better orbit fits. LOCAMS operates across the state of Arizona and records high-resolution trajectory data for hundreds of meteors per night. Both networks contribute their observations to the Global Meteor Network (GMN), which publishes publicly accessible datasets that include physically meaningful features.

We focused on directly observable parameters to ensure that our analysis is interpretable, scalable, and transferable across datasets. These include trail length, energy received, deceleration, peak brightness height, atmospheric density at multiple trajectory points (beginning, peak, end), mass and velocity in logarithmic form.

Before applying machine learning methods, the dataset was standardized using Python-based scikit-learn’s StandardScaler to ensure equal weighting across all features. This step is necessary for algorithms that rely on

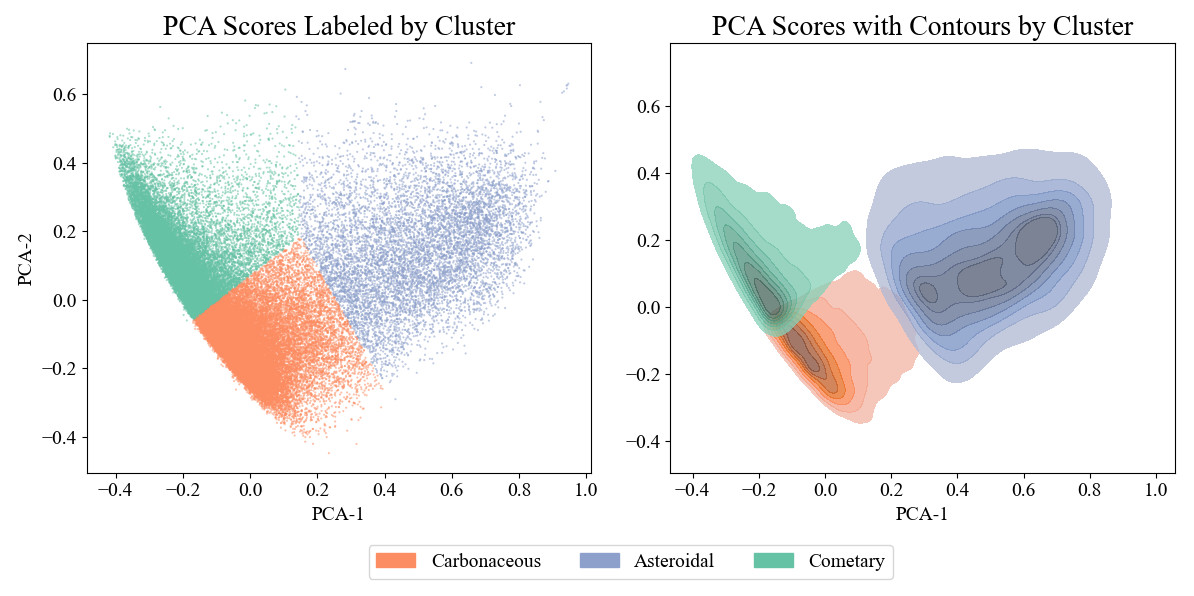

To reduce dimensionality and highlight key patterns in the data, we applied Principal Component Analysis (PCA) to the normalized feature set. PCA identifies the principal axes along which the data varies most and projects the dataset onto these axes. The first two principal components capture approximately 95% of the total variance.

The PCA matrix indicates that the first principal component (PC-1) is driven primarily by energy received (0.773) and negatively by trail length (−0.608), with smaller contributions from mass and atmospheric density. This axis appears to reflect a combination of total energy and material penetration behavior. The second principal component (PC-2) is shaped by atmospheric density at the beginning, peak, and end of the trajectory (all 0.446), along with trail length (0.350) and mass (0.249), suggesting a link to fragmentation behavior and how a meteoroid interacts with varying atmospheric conditions during entry.

After dimensionality reduction, we applied a Median Absolute Deviation (MAD) filter to further identify and remove features that contribute minimal variability to the overall dataset. For each feature, MAD was calculated as the median of the absolute deviations from that feature's median value. Features with MAD values less than 50% of the median of all MAD values were excluded. This step refined the input to include only those features contributing the most physical diversity to the dataset, leaving eight features: energy received, deceleration, beginning, peak, and end atmospheric densities, trail length, peak magnitude, and mass in kg.

To identify potential groupings within the meteor population, we applied the scikit-learn’s K-Means clustering algorithm to the PCA-transformed dataset. The elbow method was used to determine the ideal number of clusters by plotting the within-cluster sum of squares against the number of clusters and identifying the point where additional clusters no longer significantly reduce variance. Based on this analysis, three clusters were identified.

Results

Unsupervised clustering applied to the PCA-transformed dataset revealed three groups of meteoroids, which we interpret as representing carbonaceous, asteroidal, and cometary materials. The first principal component is most strongly influenced by energy received and trail length, suggesting a relationship with material strength and penetration depth. The second component highlights variation in atmospheric density and mass, which likely reflects differences in deceleration and fragmentation behavior. These clusters appear well-separated in principal component space (Figure 1), indicating physically meaningful differences in meteoroid behavior.

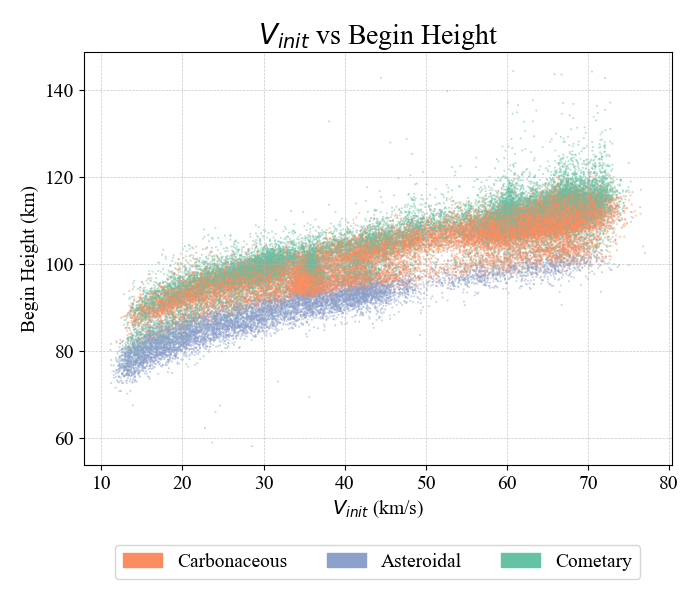

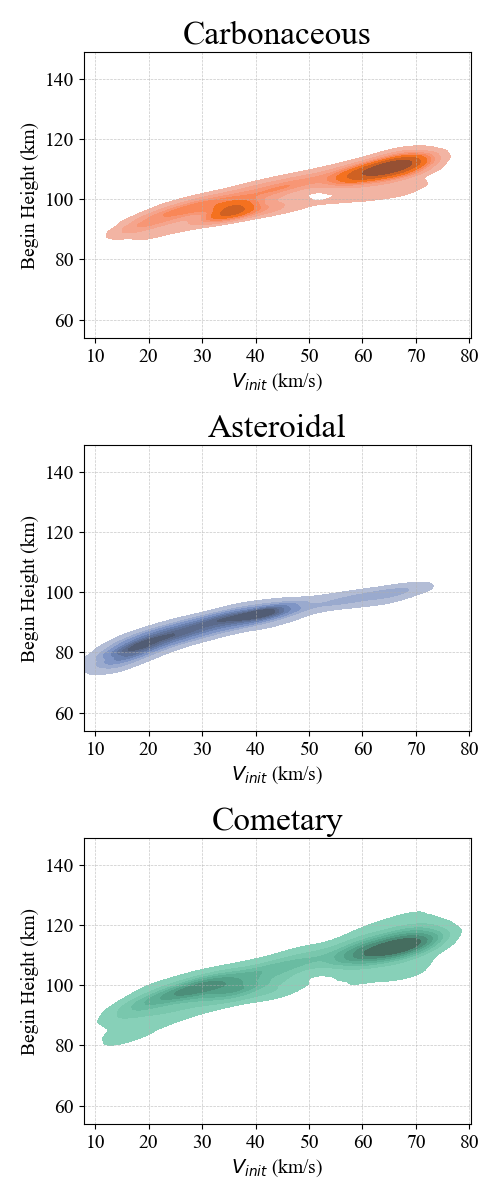

The carbonaceous-type cluster shows intermediate values across most features. The asteroidal cluster includes high-energy meteors with low deceleration and deep atmospheric penetration, traits consistent with dense, rocky material. A subset of events within this cluster may represent iron-rich meteoroids, given their unusually high energy and deep penetration. The cometary cluster contains low-mass meteors with high deceleration and higher entry altitudes, aligning with expectations for fragile, porous cometary sources. These interpretations are supported by differences in initial velocity and begin height (Figure 2), with cometary meteors tending to enter faster and at higher altitudes. Figure 3 separates the clusters into individual subplots, illustrating how the density distributions vary across each classification.

Unlike traditional methods that rely on derived quantities and model assumptions, this classification is based entirely on directly observed features. Future work will focus on linking these clusters to known meteor showers to further compare to this model.

Figure 1: PCA scores plotted as a scatter plot and color coded by physical interpretation on the left. The same scatter plot transformed into a contour plot using kernel density estimation (KDE) on the right.

Figure 2: Initial velocity vs. beginning height color coded by their physical interpretation.

Figure 3: Figure 2 transformed into individual contour plots using KDE and titled by physical interpretation.

How to cite: Hemmelgarn, S., Moskovitz, N., and Vida, D.: A Machine Learning Application to Meteor Classification, EPSC-DPS Joint Meeting 2025, Helsinki, Finland, 7–13 Sep 2025, EPSC-DPS2025-442, https://doi.org/10.5194/epsc-dps2025-442, 2025.

A reliable characterization of meteor streams from radio forward scatter observations requires corrections for both the sporadic meteor background and the observational biases introduced by equipment sensitivity and station geometry. These effects are captured through station-specific Observability Functions (OFs). Building on the approach proposed by Steyaert et al. (2006), we present a generalized modeling framework that applies exponential stream activity profiles within a constrained least-squares fitting procedure to meteor count rate time series.

To reduce ambiguity in the inversion, particularly when data are sparse or noisy, the method includes assumptions about the shape of the sporadic background and imposes constraints such as non-negativity and zero sensitivity when the radiant is below the horizon. A key improvement over the original method is the extension to multi-station datasets, which helps distinguish between stream and background components by exploiting varying observation conditions.

We apply the technique to forward scatter data from the Geminids and σ-Hydrids, recorded between 9–18 December 2019, using two stations with different antenna setups and using different transmitters. The fitted models reproduce count rates within expected uncertainties and yield plausible estimates for stream peak timing and width. The resulting OFs and background profiles differ between stations, underscoring the method's sensitivity to geometry and local conditions. While promising, the method’s performance remains dependent on input assumptions and data quality. It offers a step toward more systematic processing of radio meteor time series in distributed and heterogeneous observation networks.

References:

Steyaert, C., Brower, J., Verbelen, F., 2006. A numerical method to aid in the combined determination of stream activity and Observability Function.

How to cite: Calders, S., De Keyser, J., Lamy, H., and Kolenberg, K.: Deriving meteor stream properties from meteor count rate time series in a multi-observer network, EPSC-DPS Joint Meeting 2025, Helsinki, Finland, 7–13 Sep 2025, EPSC-DPS2025-303, https://doi.org/10.5194/epsc-dps2025-303, 2025.

This study presents a significant advancement in reconstructing meteoroid trajectories and speeds using the Belgian RAdio Meteor Stations (BRAMS) forward scatter radio network. We introduce an improved method based on a novel extension of the pre-t0 phase technique, initially developed for backscatter radars, and adapt it for continuous wave forward scatter systems. This approach leverages phase information recorded before the meteoroid reaches the specular reflection point t0 to enhance speed estimations. Furthermore, we combine this newly determined pre-t0 speed with time of flight measurements to reduce uncertainties in the reconstructed meteoroid paths and velocities. The robustness of our method is assessed using Markov Chain Monte Carlo techniques and validated against optical observations from the CAMS-BeNeLux network.

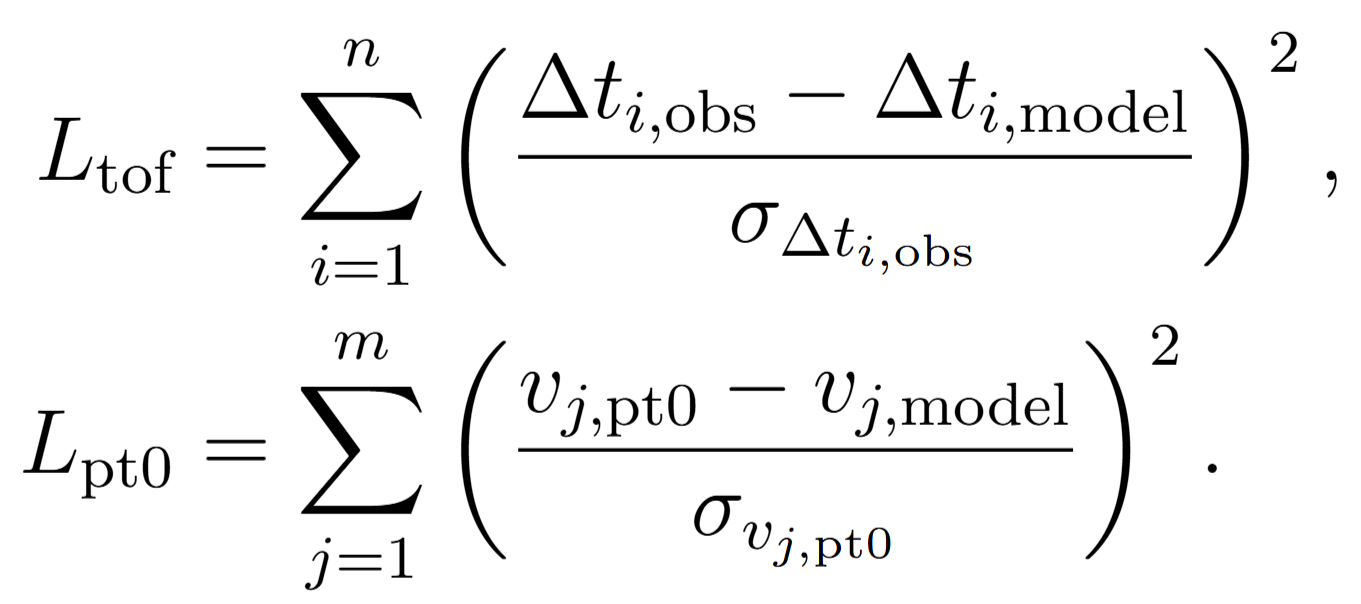

Measurement uncertainties

A critical aspect of reliable trajectory reconstruction is the accurate characterization of measurement uncertainties, particularly for the times of flight (Δt) between receiving stations. The uncertainty σΔt is closely tied to the uncertainty in determining the specular timing t0 at each station. We developed a method to determine the uncertainty σt0 as a function of two parameters: the rise time of the meteor amplitude curve (trise) and the signal-to-noise ratio (SNR).

To derive this relationship, we performed a series of Direct Monte Carlo (DMC) simulations. For each combination of trise and SNR, ideal meteor echoes were generated using the Cornu Spiral model, including some diffusion. For each SNR value, a large number of noisy clones of the ideal echo were created by adding Gaussian noise. The t0 values were extracted from these noisy echoes using the same post-processing chain as real observations, and the statistical spread σt0 was computed.

Solver improvement

Building on the measured uncertainties, we integrate them directly into the trajectory reconstruction process by redefining the cost function used by the solver:

where w is a weight parameter balancing the influence of time of flight (Ltof) and pre-t0 speed (Lpt0) measurements:

Optimizing this cost function across different values of w leads to the creation of a Pareto front representing the trade-off between minimizing the two components. The optimal solution is chosen at the "knee" of the curve, corresponding to the maximum curvature point.

Validation against optical observations

The reconstructed trajectories and speeds are compared to CAMS-BeNeLux optical data, which shows good agreement when a combination of time of flight and pre-t0 information is used. The differences are of the order of 5 % on the speed and 2-4° on the inclination.

Uncertainty propagation

To accurately quantify uncertainties on the reconstructed parameters, we employ a Markov Chain Monte Carlo approach. Assuming independent, Gaussian-distributed errors and uniform priors, the cost function L is proportional to the logarithm of the posterior probability. Thus, minimizing L is equivalent to maximizing the posterior. We use a Single Component Adaptive Metropolis-Hastings algorithm to efficiently explore the parameter space as well as to determine uncertainties and correlations.

How to cite: Balis, J., Lamy, H., Anciaux, M., Jehin, E., De Keyser, J., Kastinen, D., and Brown, P. G.: Improved meteoroid trajectory and speed reconstruction with BRAMS: pre-t0 phase technique and uncertainty quantification, EPSC-DPS Joint Meeting 2025, Helsinki, Finland, 7–13 Sep 2025, EPSC-DPS2025-1336, https://doi.org/10.5194/epsc-dps2025-1336, 2025.

Radar observations of meteor head echoes provide information about the sizes, orbital elements, and atmospheric interactions of microgram-sized dust particles entering Earth's atmosphere. Head echoes observed using MST radars enable the detection of meteoroids with masses of approximately $10^{-10} - 10^{-8}$ kg—a mass range that contributes significantly to the meteoric mass influx into Earth's atmosphere. This work presents an ongoing effort to create a catalog with over one million high-quality meteor head echoes with continuous observations made using the Middle Atmosphere ALOMAR Radar System (MAARSY) and the Program of the Antarctic Syowa MST/IS (PANSY) radars, located at 69°N and 69°S, respectively. The MAARSY catalog contains 1.6 million events, while the PANSY radar contributes an additional 0.5 million. The catalog includes data on atmospheric trajectories, Doppler shifts, and radar cross-section estimates for each meteor. Keplerian orbital elements are computed using the REBOUND numerical propagator, which is employed to remove the influence of the Earth-Moon system prior to atmospheric entry. A search for interstellar meteors provides 75 candidates. The catalogue contains meteors associated with most of the established showers, with some clusters that are not associated with any established shower. Meteors associated with multiple showers show mass dependent dispersion that is consistent with the Poynting-Robertson effect. This catalog can be used to e.g., study the distribution of micrometeoroids on Earth-crossing orbits, to analyze the atmospheric entry dynamics of meteoroids, and to study the Earth's atmosphere.

How to cite: Vierinen, J. and the MAARSY and PANSY Team: Ongoing Meteor Head Echo Surveys on the Northern and Southern Hemispheres, EPSC-DPS Joint Meeting 2025, Helsinki, Finland, 7–13 Sep 2025, EPSC-DPS2025-239, https://doi.org/10.5194/epsc-dps2025-239, 2025.

The Sun and planets are embedded in the zodiacal dust cloud, originating from comets and asteroids that shed dust through evaporation and collisions. In addition, interstellar dust from our local interstellar neighbourhood moves through the solar system and can be measured by in situ instruments on spacecraft. These interplanetary and interstellar dust measurements provide unique ground truth information about cosmic dust, complementary to astronomical observations. Since these particles are charged in the heliosphere, they also interact with the solar wind that governs the trajectories of the smallest dust particles.

The dust particles are crucial pieces of information on the origins of the solar system via their link with their parent bodies, and on the birthplaces of interstellar dust and processes in the interstellar medium. Since their trajectories are affected by the environment they move through, they can be seen as tracers for the local environment, providing additional boundary conditions for heliospheric modelling. Moreover, the zodiacal dust cloud and heliosphere are proxies for exoplanet systems with debris disks and/or astrospheres.

This talk will review the current state of the art of in situ interstellar and interplanetary dust research, comprising simulations, in situ measurements, sample return and calibration efforts, in order to provide a complementary perspective to the astronomer's view on local cosmic dust. We dive deeper into the dynamics of the smallest and the measurements of the biggest interstellar dust. The talk will end with a focus on future mission concepts that may measure interstellar and interplanetary dust near the 2030s and beyond.

How to cite: Sterken, V.: Cosmic dust in the heliosphere, EPSC-DPS Joint Meeting 2025, Helsinki, Finland, 7–13 Sep 2025, EPSC-DPS2025-1374, https://doi.org/10.5194/epsc-dps2025-1374, 2025.

This presentation concerns the impacts of cosmic dust in the atmospheres of the Earth, Mars and Venus. The input rate of cosmic dust to the Earth’s atmosphere has been very uncertain [Plane, 2012]. A recent estimate of around 28 tonnes per day globally [Carrillo-Sánchez et al., 2020] will be discussed; this was obtained using the Zodiacal Dust Cloud (or ZoDy) model [Nesvorný et al., 2011] to provide the size and velocity distributions of dust in the inner solar system, combined with the Leeds Chemical Ablation Model (CABMOD) [Vondrak et al., 2008] to determine the rate of injection of metals into the atmosphere. CABMOD is itself benchmarked using a novel Meteoric Ablation Simulator to measure the evaporation rates of metals from meteoritic particles that are flash heated, simulating atmospheric entry [Gómez-Martín et al., 2017]. The dust inputs into the atmospheres of Mars (2 t d-1) and Venus (31 t d-1) can now be constrained using the terrestrial input [Carrillo-Sánchez et al., 2020].

The ZoDy-CABMOD model provides the injection rates of the main meteoric constituents, as a function of height, location and time in the planet’s atmosphere. These injection profiles exhibit significant temporal and latitudinal variability depending on the eccentricity, obliquity and inclination of the planet’s orbit, as well as seasonal changes to the atmospheric density profile (particularly at high latitudes for the case of Mars [Carrillo-Sánchez et al., 2022]).

Detailed chemical networks for the four most abundant meteoric ablation elements - Mg, Fe, Si and Na - have been constructed from over 160 individual reactions involving neutral and ionized species [Plane et al., 2015]. For the terrestrial atmosphere these networks have been rigorously tested against observations of neutral and ionized metal atoms made with ground-based lidars, spaceborne spectrometers, and sub-orbital rockets. For Mars and Venus, we have included the chemistry of CO2, both as a reactant and a third body in recombination reactions; and for Venus a detailed chlorine chemistry is added because of the very large concentration of HCl produced by volcanic emissions. Where reactions have not been studied in the laboratory, we have employed quantum chemistry calculations combined with master equation rate theory for reactions taking place on multi-well potential energy surfaces.

These chemical networks, together with the relevant metal injection rates as a function of height, location and time, have been inserted into global chemistry-climate models: the Whole Atmosphere Community Climate Model (WACCM which extends to ~140 km, and WACCM-X which extends to ~500 km) for Earth; and the Planetary Climate Models for Mars and Venus. For Mars, model simulations generally compare well against observations of metallic ions made by instruments (IUVS and NGIMS) on NASA’s MAVEN spacecraft. In particular, the diurnal, latitudinal and seasonal variations of the Mg+ layer centred around 95 km are captured well. However, there are several interesting differences higher in the ionosphere that are currently unexplained.

In the case of Venus, metallic species have never been observed. However, the PCM-Na model predicts that the atomic Na layer around 110 km should be observable by a terrestrial telescope with a high resolution optical spectrometer, particularly on the night side and around the dawn terminator. Metallic carbonate species are also predicted to act as ice nuclei, forming transient CO2-ice clouds above 110 km in Venus’ atmosphere [Murray et al., 2023]. Metal carbonate clusters are also the probable nuclei of Martian noctilucent clouds [Plane et al., 2018]. Finally, a strong candidate for the mystery absorber in the Venusian clouds is iron trichloride (FeCl3), produced by the extra-terrestrial input of Fe and volcanic HCl.

Carrillo-Sánchez, J. D., J. C. Gómez-Martín, D. L. Bones, D. Nesvorný, P. Pokorný, M. Benna, G. J. Flynn, and J. M. C. Plane (2020), Cosmic dust fluxes in the atmospheres of Earth, Mars, and Venus, Icarus, 335, art. no.: 113395, doi:10.1016/j.icarus.2019.113395.

Carrillo-Sánchez, J. D., D. Janches, J. M. C. Plane, P. Pokorný, M. Sarantos, M. M. J. Crismani, W. Feng, and D. R. Marsh (2022), A Modeling Study of the Seasonal, Latitudinal, and Temporal Distribution of the Meteoroid Mass Input at Mars: Constraining the Deposition of Meteoric Ablated Metals in the Upper Atmosphere, Planet. Sci. J., 3(10), art. no. 239, doi:10.3847/PSJ/ac8540.

Gómez-Martín, J. C., D. L. Bones, J. D. Carrillo-Sánchez, A. D. James, J. M. Trigo-Rodríguez, B. Fegley, and J. M. C. Plane (2017), Novel Experimental Simulations of the Atmospheric Injection of Meteoric Metals, Astrophys. J., 836(2), art. no.: 212, doi:10.3847/1538-4357/aa5c8f.

Murray, B. J., T. P. Mangan, A. Määttänen, and J. M. C. Plane (2023), Ephemeral Ice Clouds in the Upper Mesosphere of Venus, J. Geophys. Res. – Planets, 128, art. no.: e2023JE007974.

Nesvorný, D., D. Janches, D. Vokrouhlický, P. Pokorný, W. F. Bottke, and P. Jenniskens (2011), Dynamical model for the zodiacal cloud and sporadic meteors, Astrophys. J., 743, 129–144, doi:10.1088/0004-637X/743/2/129.

Plane, J. M. C. (2012), Cosmic dust in the earth's atmosphere, Chem. Soc. Rev., 41, 6507-6518, doi:10.1039/C2CS35132C.

Plane, J. M. C., J. D. Carrillo-Sánchez, T. P. Mangan, M. M. J. Crismani, N. M. Schneider, and A. Määttänen (2018), Meteoric Metal Chemistry in the Martian Atmosphere, J. Geophys. Res. – Planets, 123, 695-707, doi:10.1002/2017JE005510.

Plane, J. M. C., W. Feng, and E. C. M. Dawkins (2015), The Mesosphere and Metals: Chemistry and Changes, Chem. Rev., 115(10), 4497-4541, doi:10.1021/cr500501m.

Vondrak, T., J. M. C. Plane, S. Broadley, and D. Janches (2008), A chemical model of meteoric ablation, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 8, 7015-7031, doi:10.5194/acp-8-7015-2008.

How to cite: Plane, J., Egan, J., Ceragioli, B., Feng, W., Gough, C., Marsh, D., Carrillo-Sánchez, J. D., Janches, D., Crismani, M., Schneider, N., González-Galindo, F., Stolzenbach, A., Lefèvre, F., Chaufray, J.-Y., Forget, F., Lebonnois, S., and Christou, A.: Cosmic Dust Ablation and the Metallic Layers in the Upper Atmospheres of the Terrestrial Planets, EPSC-DPS Joint Meeting 2025, Helsinki, Finland, 7–13 Sep 2025, EPSC-DPS2025-722, https://doi.org/10.5194/epsc-dps2025-722, 2025.

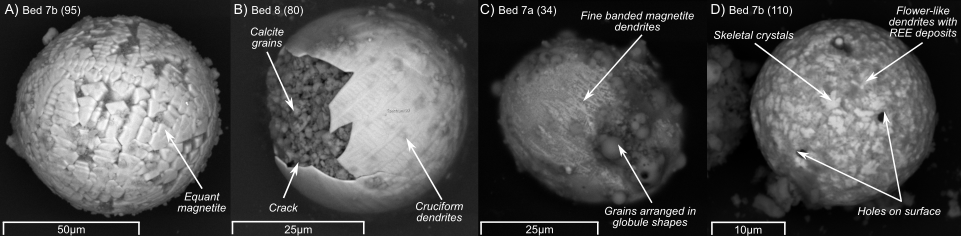

Fossil micrometeorites (MMs) are mostly I-type cosmic spherules (CSs): iron rich cosmic dust particles that have survived atmospheric entry and later preserved in sedimentary rock [1] [2]. The quantity and composition of fossil MMs can advance our understanding of dust producing bodies in the solar system throughout Earth’s history, providing ground-truth empirical evidence of previous asteroid break-up events and cometary showers that would have otherwise remain undiscovered [3] [4] [5]. Their abundances and estimates of local sedimentation rates have been used to reconstruct the past flux of extraterrestrial dust [6] [7], but the influence of terrestrial or sampling processes ultimately affecting these calculations were ignored (e.g. diagenesis [8] or separation techniques). The cause for difference in CS concentration found throughout a Cenomanian succession in Dorset, England is discussed here, focusing on possible explanatory terrestrial and solar system processes utilising spherule quantification, petrography and geochemistry. Additionally, numerical models simulating changes in micrometeoroid size during entry heating are also used to study the possible entry parameters, sources, and solar system events acting as causes for changes in flux .

To determine changes in CS concentration, 2-10kg of chalk/marl from 5 horizons in the South England Chalk Group in Lulworth Cove, Dorset were analysed. Each sample was processed by a rock crusher and then placed into an electric vibrating sieve to separate the dust fractions (<250µm) which were then magnetically separated three times and optically examined to find CSs following protocols described in [1]. The CSs external petrographic textures and qualitative geochemistry were acquired using a desktop Hitachi TM4000Plus SEM and JEOL JXA-8530F EPMA.

The numerical models used closely resemble those discussed in [9]. Atmospheric deceleration was obtained using a simulation based on the model of [10] where deceleration is calculated from the momentum loss of spherical particles due to collisions with atmospheric gas molecules in its flight path. The final radius of particles is calculated using a balance of mass gained by oxidation (assuming every encountered oxygen molecule reacts and is incorporated with the molten iron) and evaporative mass loss.

All sediment samples returned numerous CSs, totalling 481 – the majority being I-types, but some are characterised as potential altered S-types (silicate rich CSs) or G-types (intermediate composition CSs). A minority presented unusual features such as cracks, mottled exteriors, and skeletal magnetite crystals (Figure 1). Most I-types showed similar chemical spectra with high Fe peaks, minor Ti and Mn implantation and variable amount of Si and Al (mostly on the exterior). Sample “Bed 8” yielded the highest number of spherules (>3x the others) normalised to 142 CS/kg of dust. The diameters ranged from 12µm to 130µm, and the mean values were between 24µm and 36µm which is comparable to other fossil MM studies [7] [8].

Almost all particles in the simulated conditions reach peak temperatures above the solidus for iron oxides (1809oK), causing them to melt and become CSs. To create the smallest sized I-types in this study (<25µm), ~25µm-sized micrometeoroids must enter at >14km/s at ~90o. At 18km/s <25µm I-types can be generated in a wider range of settings, encompassing micrometeoroids with initial sizes of up to ~350µm entering at >~75o. At higher velocities, evaporative loss and peak temperatures are too high for dust to survive in most set conditions.

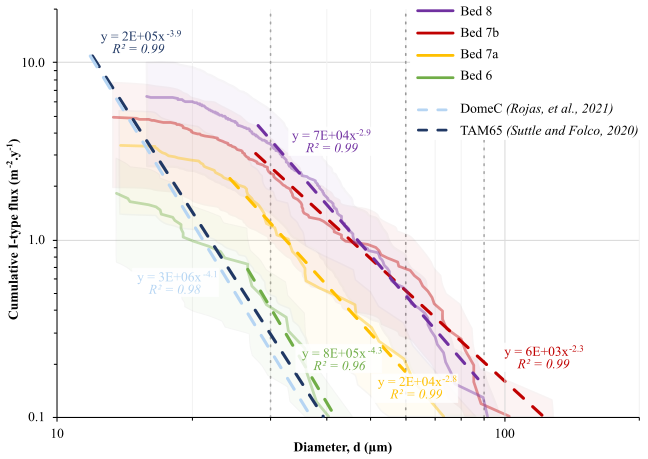

The retention of characteristic quenched dendritic textures, preservation of intact metal beads, detectable Ni and Cr in some samples, and the sub-mm size and spherical nature of the particles indicate these Fe-oxides are extraterrestrial I-types. Since the sampled beds are geologically equivalent, contiguous, have similar accumulation periods and were processed using identical protocols, the high CS/kg concentration of Bed 8 likely represents a significant change in flux rates during the Cenomanian, rather than terrestrial or sampling influences. The enhancement in I-type accumulation rate (given in m-2.yr-1) was calculated by integrating power lines fitted on flux vs diameter plots for each bed and modern-day values (using [11] as the background; Figure 2). The ratios of the integrals reveal Bed 8 had an enhancement factor of >20x for I-types between 30 and 90µm in size, presenting a clear spike in flux.

The results of the numerical simulations show high entry velocities and angles are required to produce the small sizes of I-types discovered in this study, implying the dominating source of dust had an elliptical orbit such as from a cometary flyby. However, the lower power law exponents of the beds compared to those of modern day could indicate that most dust had lower velocities, which may suggest an asteroidal origin [10]. Further work will refine the possibilities of solar system events leading to this CS enrichment by discussing influences on these calculations and source assumptions.

[1] M. J. Genge, et al. (2008) Meteorit. Planet. Sci., 43(3): 497–515. [2] M. Genge, et al. (2020) Planet. Space Sci., 187: 104900. [3] B. Schmitz, et al. (1997) Science, 287: 88-90. [4] P. R. Heck, et al. (2008) Meteorit. Planet. Sci., 43: 517-528. [5] G.G. Voldman, et al. (2013) Geol. J., 48: 222–235 [6] S. Taylor and D. E. Brownlee (1991) Meteorit. Planet. Sci., 26(3): 203-211. [7] T. Onoue, et al. (2011) Geology, 39(6): 567-570. [8] M. D. Suttle and M. J. Genge (2017) Earth Planet. Sci. Lett., 476: 132-142. [10] S. G. Love & D. E. Brownlee (1991) Icarus, 89: 26-43. [11] J. Rojas, et al. (2021) Earth Planet. Sci. Lett., 560: 116794. [12] M. D. Suttle & L. Folco (2020) J. Geophys. Res. Planets, 125(2).

Figure 1. SEM images of fossil I-type cosmic spherules (CSs).

Figure 2 The cumulative I-type flux (m-2.yr-1) plotted against diameter of spherules. Dashed lines represent power lines fitted to the main population of spherules. The blue dashed lines are extrapolated fitted power lines for [11] and [12]. The shaded regions show errors in the sedimentation rate used. The flux assumes <5% of their collection consists of I-types. The grey dotted lines show the regions selected to represent medium-sized, and large spherules in the study (d = 30 to 60µm, 60 to 90µm).

How to cite: Mattia, I., Genge, M., Suttle, M., and Wong, A.: An Estimate of Cenomanian Cosmic Dust Flux: Implications on Their Identification, Sources, and Mass Contribution Calculations, EPSC-DPS Joint Meeting 2025, Helsinki, Finland, 7–13 Sep 2025, EPSC-DPS2025-1793, https://doi.org/10.5194/epsc-dps2025-1793, 2025.

Please decide on your access

Please use the buttons below to download the supplementary material or to visit the external website where the presentation is linked. Regarding the external link, please note that Copernicus Meetings cannot accept any liability for the content and the website you will visit.

Forward to presentation link

You are going to open an external link to the presentation as indicated by the authors. Copernicus Meetings cannot accept any liability for the content and the website you will visit.

We are sorry, but presentations are only available for users who registered for the conference. Thank you.

1. Introduction

The Fireball Recovery and Inter Planetary Observation Network (FRIPON) network [1] has been monitoring the sky with the use of optical all-sky cameras and radio receivers with the scope of detecting fireball events. The list of all-sky cameras installed so far, as well as the meteor detections can be found online on the FRIPON site [2].

We focus this research on the latest fireballs detected by the Meteorite Orbits Reconstruction by Optical Imaging (MOROI) cameras [3].

2. Methods

The atmospheric trajectory is determined with a method elaborated in order to overcome the distortion caused by the fish-eye lens [4]. The 3D trajectory can be determined for the events detected by multiple cameras [4], [1]. Starting from the luminous trajectory, we can derive the ballistic coefficient α and mass loss parameter β [5], [6]. Those parameters help us to determine whether the meteoroid is likely or not to reach Earth’s surface [7], [8]. The light curve of the meteor allows us to determine the initial and final mass of the meteoroid, as well as the time the meteoroid fragmented. The luminosity and the luminous efficiency are determined using the methods presented in [9].

3. Results

We make graphic representations of the light curves of some of the latest fireball events recorded by the MOROI component of the FRIPON network. We present the luminous trajectory and derive the parameters that result from it. We determine the height and the time of fragmentation for the studied fireball events. We compute the initial and final mass of the analysed meteoroids.

References

[1] Colas, F., Zanda, B., Bouley, S., Jeanne, S., Malgoyre, A., Birlan, M., Blanpain, C., Gattacceca, J., Jorda, L., Lecubin, J., et al. (385 more) FRIPON: a worldwide network to track incoming meteoroids. Astronomy &. Astrophys. 644, A53. 2020.

[2] https://fireball.fripon.org/

[3] Nedelcu, D.A., Birlan, M., Turcu, V., Boaca, I., Badescu, O., Gornea, A., Sonka, A.B., Blagoi, O., Danescu, C., Paraschiv, P. Meteorites Orbits Reconstruction by Optical Imaging (MOROI) Network. Romanian Astronomical Journal 28(1), 57 – 65. 2018.

[4] Jeanne, S., Colas, F., Zanda, B., Birlan, M., Vaubaillon, J., Bouley, S., Vernazza, P., Jorda, L., Gattacceca, J., Rault, J. L., Carbognani, A., Gardiol, D., Lamy, H., Baratoux, D., Blanpain, C., Malgoyre, A., Lecubin, J., Marmo, C., Hewins, P. Calibration of fish-eye lens and error estimation on fireball trajectories: application to the FRIPON network. Astronomy and Astrophysics, 627:A78. 2019.

[5] Gritsevich, M. I., The Pribram, Lost City, Innisfree, and Neuschwanstein falls: An analysis of the atmospheric trajectories. Solar System Research.42, 372–390. 2008.

[6] Gritsevich, M.I. Determination of parameters of meteor bodies based on flight observational data. Advances in Space Research 44(3):323–334. 2009.

[7] Sansom, E.K., Gritsevich, M., Devillepoix, H.A.R., Jansen-Sturgeon, T., Shober, P., Bland, P.A., Towner, M.C., Cupák, M., Howie, R.M., Hartig, B.A.D. Determining Fireball Fates Using the α-β Criterion. Astrophysical Journal 885(2):115. 2019.

[8] Boaca, I., Gritsevich, M., Birlan, M., Nedelcu, A., Boaca, T., Colas, F., Malgoyre, A., Zanda, B., Vernazza, P. Characterization of the fireballs detected by all-sky cameras in Romania. Astrophysical Journal 936(2):150. 2022.

[9] Gritsevich, M. and Koschny, D. Constraining the luminous efficiency of meteors. Icarus 212(2): 877-884. 2011.

How to cite: Boaca, I. L., Colas, F., Malgoyre, A., Zanda, B., and Vernazza, P.: Properties of FRIPON meteoroids deriving from the luminous trajectory, EPSC-DPS Joint Meeting 2025, Helsinki, Finland, 7–13 Sep 2025, EPSC-DPS2025-43, https://doi.org/10.5194/epsc-dps2025-43, 2025.

Ursa Astronomical Association (https://www.ursa.fi/english.html) (founded 1921) is the biggest astronomical association in Finland. By membership count (over 19000 members) it is also one of the largest scientific associations in the world. Ursa runs an observational database called “Skywarden” (or “Taivaanvahti” in Finnish). Citizen observations of many types of celestial phenomena are collected including fireballs. The system is accessible both in English and Finnish. Ursa Astronomical Association also provides an umbrella organization for Finnish Fireball Network connecting scientists from different universities, camera station owners and citizen scientists.

The database contains about 20000 fireball observations in May 2025 (the system was established in 2011). Quite many of those observations are linked to the same fireball event even though there are also sporadic cases. The authors have developed an algorithm to group the fireballs belonging to a certain event. The algorithm runs automatically in the background. Altogether there are a few hundred cases of fireball events.

The Skywarden system had a crucial role in finding the Annama meteorite (Trigo-Rodriguez et al.). The video images posted to the database were used to determine the strewn field. In addition, a meteor on a hyperbolical track was identified from the user submitted images and the orbit of the meteor could be determined (Peña-Asensio et al.).

However, most of the observations in the database are without video images since they come from laymen. Usually, special hardware is required to retrieve images of meteors but nowadays surveillance cameras and dashcams do provide some material. In some cases, the citizen observations can provide auxiliary information to video images like if sound phenomena were observed. Daytime fireballs are rarely recorded since the special cameras are too sensitive during daylight. The authors wanted to investigate how well the citizen observations without any photos can be used to estimate the luminous track of the fireball.

The database collects information of the observer, date, location, duration of the phenomenon, bearing of the fireball, the apparent altitude, and the angle it came down. More information can be provided such as images, information on the sound phenomena etc. If the location is provided as a name, the system polls coordinate from Google Maps API. Skywarden provides data through its own API. It is possible to search for fireball events or displays and then fetch all the observations easily.

To analyze the data the data is fetched from Skywarden API. A Python Pandas based script preprocesses the data. All information that contains angular data (bearing, altitude, inclination angle) is added to the table. The data can then be exported in many formats like json, csv etc.

The authors developed two methods to analyze the data. The first one gives a crude estimate of the geographical location of the end of the luminous track only. For each observation pair the cross points of a major circle using bearings are calculated. Only those over Finland are preserved. The vector average of the point cloud is taken as the estimate. This is system is fast and is implemented as a web service that can calculate the estimate on the fly and visualize it on a map.

The authors developed also a second method that guesses a large set of the coordinates of the luminous track, then projects it to all observers and using least squares the best fit is then selected for the next round. This continues until the estimate isn’t improved significantly anymore. This method is slower and doesn’t give near real time results. However, it is possible to run in the background and thus provide an estimate for every fireball case automatically.

The Finnish Fireball Network does the estimation of the meteor tracks using video images. Some prominent fireballs with potential meteorite were used to compare the results obtained from the citizen observations only. The worst-case distance with the fast method was 73 km whereas with the least squares method the distance was 45 km. In average the quick method was off 44 km and the least squares method 26 km. A prominent fireball was seen in Vätsäri, Finnish Lapland on Nov 16, 2017. In Fig. 1 the results are presented on a map.

Figure 1 Results of Vätsäri case (Nov 16, 2017) on a map (Map data copyrighted OpenStreetMap contributors and available from https://www.openstreetmap.org). Red arrow denotes the flight path estimated from video observations, green path is the least squares estimated flight path, blue is obtained using the quick algorithm. The ellipsoid is the video based estimated strewn field.

The results were surprisingly good even though alone they are not sufficient to justify a field trip. The least squares algorithm is rather easy to use with mixed set of citizen observations and video-based estimates. In some cases, there is only one video observation and augmenting with citizen data would give at least some idea of the luminous track.

The spherical Earth model was used so integrating ellipsoid model and DEM would probably be a good next step of development. Also, the bearings are presented in quite a coarse manner. Maybe a mobile phone app would be appropriate to mitigate this. It would also help to improve the accuracy of grouping of observations.

References:

Trigo-Rodríguez, J.M., Lyytinen, E., Gritsevich, M., Moreno-Ibáñez, M., Bottke, W. F., Williams, I., Lupovka, V., Dmitriev, V., Kohout, T. and Grokhovsky, V. 2015, Orbit and dynamic origin of the recently recovered Annama's H5 chondrite, Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society, vol. 449, iss. 2, May 11, pp. 2119–2127, doi: 10.1093/mnras/stv378.

Peña-Asensio, E., Visuri, J., Trigo-Rodríguez, J. M., et al. 2024, Oort cloud perturbations as a source of hyperbolic Earth impactors, Icarus, Vol. 408, doi: 10.1016/j.icarus.2023.115844.

How to cite: Takala, M., Bruus, E., Moilanen, J., Mäkelä, V., and Pekkola, M.: Estimating fireball luminous tracks using citizen observations, EPSC-DPS Joint Meeting 2025, Helsinki, Finland, 7–13 Sep 2025, EPSC-DPS2025-305, https://doi.org/10.5194/epsc-dps2025-305, 2025.

BRAMS (Belgian RAdio Meteor Stations) is a network using forward scatter of radio waves on ionized meteor trails to detect and characterize meteoroids. It is made of a dedicated transmitter and of 50 receiving stations located in or near Belgium. The transmitter emits a circularly polarized CW radio wave with no modulation at a frequency of 49.97 MHz. One of the receiving stations is an interferometer using the Jones configuration.

Since there is no information available on the range traveled by the radio wave, the only data that can be used to reconstruct the meteoroid trajectory and speed is the time delays measured between the time t0 of appearance of the meteor echo at various receiving stations (assuming specularity of the reflection). The problem is ill-posed since a small error on the measurement of t0 (of the order of a few ms) can lead to a strong error on the reconstruction (Balis et al., 2023). Therefore there is a need for additional constraints that can come e.g. from pre-t0 phase measurements at some of the stations. Indeed, in Balis et al. (2025), it is shown that these measurements systematically improve the reconstruction, sometimes by an order of magnitude.

Here, we study another possibility to constrain the speed of the meteoroid by looking at phases computed using the Fourier transform (FT) of the meteor echo. This method was proposed for back scattering meteor radars by Korotyshkin (2024) but is applied here for the first time to a forward scatter system using BRAMS data. The method will be explained in detail, emphasizing the modifications we introduce due to the forward scatter geometry on one hand, and the fact that BRAMS transmits a CW signal instead of pulses on the other hand. The advantage of the method is to increase the signal-to-noise ratio by combining samples from the entire meteor echo. Hence, in principle, it can be applied to fainter meteor echoes. We present preliminary tests on BRAMS data with the aim in the future to incorporate the constraints put on the meteoroid speed into our trajectory solver.

References :

- Balis, J. et al., Reconstructing Meteoroid Trajectories Using Forward Scatter Radio Observations From the BRAMS Network, Radio Science, 58, 2023. https://doi.org/10.1029/2023RS007697

- Balis, J. et al., Enhanced meteoroid trajectory and speed reconstruction using a forward scatter radio network: pre-t0 phase technique and uncertainty analysis, submitted to Radio Science, 2025