EXOA17

Dynamics and stability of extrasolar systems

Orals FRI-OB4

|

Fri, 12 Sep, 14:00–16:00 (EEST) Room Neptune (rooms 22+23)

Posters THU-POS

|

Attendance Thu, 11 Sep, 18:00–19:30 (EEST) | Display Thu, 11 Sep, 08:30–19:30 Finlandia Hall foyer, F227–231

In this session, we address the question of the intricate dynamical evolution of RV-detected systems and transit-detected planetary systems, where resonant and chaotic processes emerge from complex gravitational interactions. Additional effects, including tidal forces, general relativistic effects, planet-disc interactions, and the gravitational influence of binary companions, can strongly affect the architecture and long-term stability of such systems.

This session aims to explore how theoretical modeling can provide crucial insights into system characterization by confronting dynamical predictions with observational constraints, highlighting how dynamical constraints inform our interpretation of planetary system architectures from initial formation to long-term evolutionary states.

Session assets

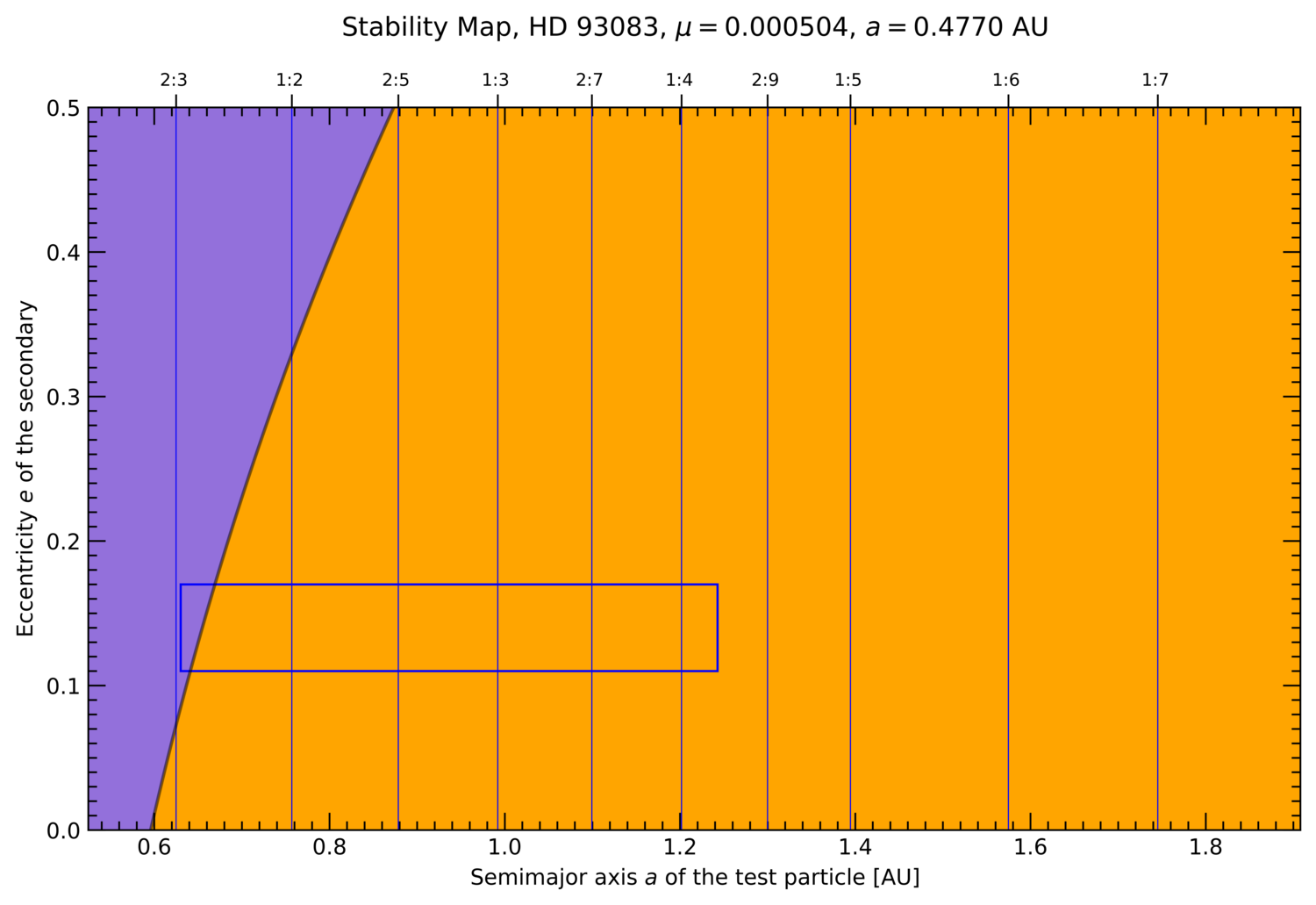

Stability

14:00–14:12

|

EPSC-DPS2025-608

|

ECP

|

On-site presentation

14:12–14:24

|

EPSC-DPS2025-1555

|

On-site presentation

14:24–14:36

|

EPSC-DPS2025-1893

|

ECP

|

On-site presentation

14:36–14:48

|

EPSC-DPS2025-633

|

On-site presentation

System evolution

14:48–15:00

|

EPSC-DPS2025-784

|

ECP

|

On-site presentation

15:00–15:12

|

EPSC-DPS2025-1121

|

On-site presentation

Dynamics

15:12–15:24

|

EPSC-DPS2025-310

|

On-site presentation

15:24–15:36

|

EPSC-DPS2025-1993

|

ECP

|

On-site presentation

15:36–15:48

|

EPSC-DPS2025-223

|

ECP

|

On-site presentation

15:48–16:00

|

EPSC-DPS2025-1996

|

On-site presentation

F227

|

EPSC-DPS2025-1120

|

ECP

|

On-site presentation

F229

|

EPSC-DPS2025-2046

|

On-site presentation

F230

|

EPSC-DPS2025-15

|

On-site presentation

F231

|

EPSC-DPS2025-2052

|

On-site presentation