Oral presentations and abstracts

Since the discovery of the first exoplanet in 1995 more than 4000 exoplanets have been detected to date. This indicates that planet formation is a robust mechanism and nearly every star in our Galaxy should host a system of planets.

However, many crucial questions about the origin of planets are still unanswered: How and when planets formed in the Solar System and in extra-solar systems? Are protoplanetary disks massive enough to form the planets cores? And what chemical composition do planets and primitive Solar System bodies inherit from their natal environment? Is the chemical composition passed unaltered from the earliest stages of the formation of a star to its disk and then to the bodies which assemble in the disk? Or does it reflects chemical processes occurring in the disk and/or during the planet formation process?

A viable way to answer these questions is to study the planets formation site, i.e. protoplanetary disks. In the recent years, the advent of ALMA and near-infrared/optical imagers aided by extreme adaptive optics revolutionised our comprehension of planet formation by providing unprecedented insights on the protoplanetary disks structure, both in its gaseous and solid components.

The aim of this session is to review the latest results on protoplanetary disks; to foster a comparison with the recent outcomes of small bodies space missions (e.g. Rosetta, Dawn, Hayabusa 2, OSIRIS-REX) and ground-based observations; and to discuss how these will affect the current models of planet formation and can guide us to investigate the origin of planets and small bodies and of their chemical composition.

Session assets

Exoplanetary science is now pushing to constrain the atmospheric compositions of exoplanets. This quest will be further aided by the next generation of facilities, such as the JWST and ground-based ELTs. Linking the observed composition of exoplanet atmospheres to where and how these atmospheres formed in their natal protoplanetary disks often involves comparing the observed exoplanetary atmospheric carbon-to-oxygen (C/O) ratio to a model of a disk midplane with a fixed chemical composition. In this scenario, chemical evolution in the midplane prior to and during the planet formation era is not considered. The C/O ratios of gas and ice in the disk midplane are simply defined by icelines of volatile molecules such as water and CO in the midplane. However, kinetic chemical evolution during the lifetime of the gaseous disk can change the relative abundances of volatile molecules, thus altering the C/O ratios of the planet-forming material. In my chemical evolution models, I utilize a large network of gas-phase, grain-surface and gas-grain interaction reactions, thus providing a comprehensive treatment of chemistry. In my talk, I will outline how such chemical reactions can cause the chemical composition in the disk midplane to evolve, how this affects the C/O ratios of the gas and solid material that form planets, and how such changes to the midplane chemical composition can lead to differences in exoplanet atmospheric compositions. These differences in exoplanet atmospheric compositions may be discernible with JWST observations.

How to cite: Eistrup, C.: From disk midplanes to exoplanet atmospheres. The volatile chemical link., Europlanet Science Congress 2020, online, 21 Sep–9 Oct 2020, EPSC2020-48, https://doi.org/10.5194/epsc2020-48, 2020.

Snow-lines are thought to play a vital role in the evolution of protoplanetary discs and planet formation at all scales. Snow-lines occur in regions of the protoplanetary discs where the temperature reaches the sublimation temperature and volatiles transition from the solid phase to the vapour phase (or vice-versa). However, in the outer region of protoplanetary discs (beyond a few AU), the temperature is set by the distribution of solids and their ability to absorb stellar light. Thus, the thermodynamics of the disc and the volatile phases are inextricably linked. In this talk, I will show this coupling is thermally unstable, and snow-lines continually evolve in regions of the disc that are marginally optically thick. Patches of the disc proceeding through a limit cycle, where volatiles in a region of the disc continually condense and then sublimate. Using numerical simulations of the CO snow-line I will show it can move 10s AU over 10,000 years, repeatedly. I will use these simulations to discuss how this new process may effect measured Carbon abundances, solid evolution and ultimately planet formation, making connections to high-resolution images of protoplanetary discs.

How to cite: Owen, J.: The dance of snow-lines, Europlanet Science Congress 2020, online, 21 Sep–9 Oct 2020, EPSC2020-207, https://doi.org/10.5194/epsc2020-207, 2020.

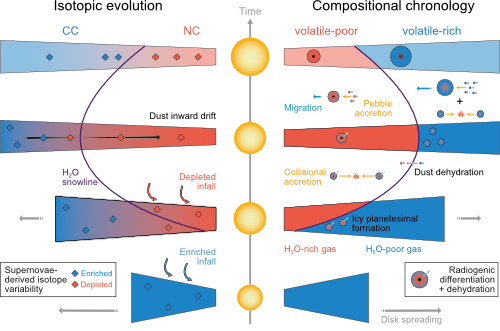

How to cite: Lichtenberg, T., Dra̧żkowska, J., Schönbächler, M., Golabek, G. J., and Hands, T. O.: Earliest isotopic and chemical bifurcation of planetary building blocks, Europlanet Science Congress 2020, online, 21 Sep–9 Oct 2020, EPSC2020-243, https://doi.org/10.5194/epsc2020-243, 2020.

Protoplanets formed by core accretion can become massive enough to accrete gas from the disk they are born in. If the

planetary proto-atmosphere exceeds a critical mass, runaway gas accretion starts and the planetary atmosphere collapses into a gas

giant. In recent years, many close-in super-Earths have been observed which raises the question on how they avoided becoming hot

Jupiters. We investigate the recycling hypothesis as a possible mechanism to avoid the collapse of the atmosphere.

We use three-dimensional radiation-hydrodynamics to simulate the formation of proto-atmosphere in the local frame around

the planet. In post-processing we use tracer particles to calculate the shape of the atmosphere and determine the non-uniform recycling

timescale in a quantitative manner. Our simulations converge to a quasi-steady state where the velocity field of the gas does not change anymore. For the

parameter space explored, a = 0.1 au, m_c ∈ [1, 2, 5, 10] M_Earth, we find that recycling of the atmosphere counteracts the collapse by

preventing the gas from cooling efficiently.

How to cite: Moldenhauer, T., Kuiper, R., Kley, W., and Ormel, C.: Recycling of Planetary Proto-Atmospheres, Europlanet Science Congress 2020, online, 21 Sep–9 Oct 2020, EPSC2020-390, https://doi.org/10.5194/epsc2020-390, 2020.

Identifying planets around O-type and B-type stars is inherently difficult; the most massive known planet host has a mass of only about 3 M⊙ . However, planetary systems which survive the transformation of their host stars into white dwarfs can be detected via photospheric trace metals, circumstellar dusty and gaseous discs, and transits of planetary debris crossing our line of sight.

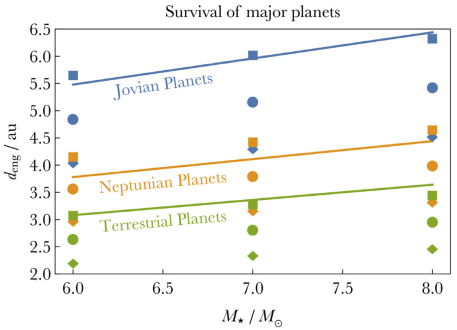

These signatures offer the potential to explore planet formation efficiency and chemical composition for host stars with masses up to the core-collapse boundary at ≈ 8 M⊙ , a mass regime rarely investigated in planet formation theory. Here, we establish limits on where both major and minor planets must reside around ≈ 6–8 M⊙ stars in order to survive into the white dwarf phase. For this mass range, we find that intact terrestrial or giant planets need to leave the main sequence beyond approximate minimum star–planet separations of, respectively, about 3 and 6 au, as shown here:

Further, in these systems, rubble pile minor planets of radii 10, 1.0, and 0.1 km would have been shorn apart by giant branch radiative YORP spin-up if they formed and remained within, respectively, tens, hundreds, and thousands of au, as shown here:

Overall, we find that planet formation around 6 M⊙-8 M⊙ stars may be feasible, and hence we encourage dedicated planet formation investigations for these systems.

How to cite: Veras, D., Tremblay, P.-E., Hermes, J., McDonald, C., Kennedy, G., Meru, F., and Gänsicke, B.: Constraining planet formation around 6-8 M☉ stars, Europlanet Science Congress 2020, online, 21 Sep–9 Oct 2020, EPSC2020-412, https://doi.org/10.5194/epsc2020-412, 2020.

We present a new numerical framework to model the formation and evolution of giant planets. The code is based on the further development of the stellar evolution toolkit Modules for Experiments in Stellar Astrophysics (MESA).

The model includes the dissolution of the accreted planetesimals/pebbles in the planetary gaseous envelope, and the effect of envelope enrichment on the planetary growth and internal structure is computed self-consistently.

We apply our simulations to Jupiter and investigate the impact of different heavy-element and gas accretion rates on its formation history.

We show that the assumed runaway gas accretion rate significantly affect the planetary radius and luminosity.

It is confirmed that heavy-element enrichment leads to shorter formation timescales due to more efficient gas accretion.

We find that with heavy-element enrichment Jupiter's formation timescale is compatible with typical disks' lifetimes even when assuming a low heavy-element accretion rate (oligarchic regime).

Finally, we provide an approximation for the heavy-element profile in the innermost part of the planet, providing a link between the internal structure and the planetary growth history.

How to cite: Valletta, C. and Helled, R.: Giant planet formation models with a self-consistent treatment of heavy-element., Europlanet Science Congress 2020, online, 21 Sep–9 Oct 2020, EPSC2020-648, https://doi.org/10.5194/epsc2020-648, 2020.

1. Introduction:

In the traditional core accretion scenario, a planet grows by the subsequent accretion of a solid core and a gaseous envelope [3]. However, the accretion of these solids generates a large amount of heat, which can easily vaporize incoming pebbles and fractured planetesimals before the core has grown massive [1,4,5]. This naturally leads to the formation of planets with polluted envelopes that are characterized by different interior conditions and that follow an altered evolutionary pathway. In this series of papers [1,2+forthcoming], we develop new analytical and numerical models to describe the formation and evolution of polluted planets and link emerging trends in their formation to observations of planetary systems.

2. Formation of polluted planets:

Fig. 1. A sketch of the four potential evolutionary phases of a polluted planet.

We find that envelope pollution substantially alters the structure of proto-planets in a number of ways and we suggest that their evolution can be described by four distinct phases, sketched in Fig. 1.

(I). In the first phase of direct core growth, the envelope is still cold enough for solids to reach the central core. As the planet's internal temperatures rise, an increasing fraction of the accreting solids sublimates and is absorbed in the envelope. This slows down the growth of the core until it halts completely when all incoming solids become vaporized and remain in the envelope. We find that in the case of pebble accretion, this limits the size of the central cores to ‹ 1-2 M⊕, depending on conditions.

(II). We refer to the second phase as that of envelope growth, as this is where all the accreted solids end up after direct core growth ends. In our analytical model, we assume that it mixes efficiently with the nebular gas but we relax this assumption in a forthcoming numerical work. Regardless, we find that polluted interiors become very hot and dense due to a higher mean molecular weight, lower adiabatic index and smaller core. Interior temperatures can already reach values in excess of 104 K at only a few Earth masses. Traditional models use the critical core mass as a criterion to identify the transition to runaway gas accretion but this term becomes a meaningless in planets that do not grow their cores beyond a certain size. We therefore suggest the critical metal mass (Mz,crit) as an equivalent criterion to supercede it. It is defined as the total mass in solids (core + vapor) that a planet needs to accrete in order to reach runaway growth. We derive the first expression for this mass:

where κrcb is the opacity at the radiative-convective boundary, d is the planet's semi-major axis, Tvap is the vaporization temperature of the solids, is their accretion rate and Mc is the mass of the central core. Planets that form beyond the ice-line accrete a larger fraction of volatile materials and therefore form smaller cores with material that is characterized by lower vaporization temperatures. Both these effects reduce the critical metal mass compared to the inner disk where super-Earths and mini-Neptunes are more resistant to runaway gas accretion.

(III). If a planet stops accreting solids before it reaches runaway accretion and while the disk is still present, it enters a phase of embedded cooling. This naturally happens in pebble accretion when a planet reaches the pebble isolation mass and begins to perturb the surrounding disk. The continued inward drift of tiny dust allows the planet to maintain a high opacity, limiting the pace of cooling. Besides this, the dilution of the interior can counteract the contraction of the envelope and further limit nebular accretion, although this requires the interior to remain compositionally mixed. We suggest that a combination of these effects can help explain why Uranus and Neptune did not reach runaway gas accretion, even if their solids flux dried up while the disk was still present.

(IV). Finally, the proto-planetary disk will dissipate and the planets eventually enter phase IV of isolated cooling. In traditional models, this is mainly associated with contraction and potential mass loss. We suggest that in the case of a polluted planet, the cooling will eventually lead to the rainout of the vapor interior and generate a second phase of (indirect) core growth after several Gyr. While the process of photo-evaporation should not be altered by this, we find that it makes internal energy release an ineffective mass-loss mechanism. This is because most of the energy is only liberated late in the planet's evolution after substantial contraction, when mass loss from winds is far less efficient.

2.1 Opacity in pebble accretion

Fig. 2. Trends in the critical metal mass from the opacity of gas, dust and pebbles.

We model the opacity during pebble accretion in a forthcoming work with a combination of molecular, dust and pebble contributions. We find that pebbles can effectively reduce the dust abundance through sweep-up, but only in the early stages when nebular gas accretion is outpaced by the pebble flux. Near the onset of runaway accretion, the opacity displays a dichotomy between the hot inner disk where molecular opacity dominates and the outer disk where dust obscures the envelopes. The result is an opacity valley around 1-3 AU that translates to an equivalent minimum in the critical metal mass at the same location (see Fig. 2), which can help explain the abundance of warm Jupiters in this region.

Acknowledgements:

This work has benefited from discussions at the ISSI Ice Giants Meetings in Bern 2019 & 2020. Marc Brouwers acknowledges the support of a Royal Society Studentship, RG 160509.

References:

[1] Brouwers, M. G., Vazan, A., & Ormel, C. W. 2018, A&A, 611, A65

[2] Brouwers, M. G. & Ormel, C. W. 2020, A&A, 634, A15

[3] Pollack, J. B., Hubickyj, O., Bodenheimer, P., et al. 1996, Icarus, 124, 62

[4] Mordasini, C., Mollière, P., Dittkrist, K.-M., Jin, S., & Alibert, Y. 2015, International Journal of Astrobiology, 14, 201

[5] Valletta, C. & Helled, R. 2019, ApJ, 871, 127

How to cite: Brouwers, M., Ormel, C., Vazan, A., and Bonsor, A.: The evolutionary pathway of polluted proto-planets, Europlanet Science Congress 2020, online, 21 Sep–9 Oct 2020, EPSC2020-1039, https://doi.org/10.5194/epsc2020-1039, 2020.

The study of dust agglomeration has been a prevalent subject in laboratory astrophysics since its inception. It aims to bridge the gaps in our understanding of early planet formation and helps us interpret the data we receive from telescopes like ALMA, which observe protoplanetary disks.

As a contribution to this field, the ICAPS experiment (Interactions in Cosmic and Atmospheric Particle Systems) studies the agglomeration of micrometer-sized, monomeric silica grains under microgravitational conditions. To achieve stable microgravity, the experiment flew onboard the Texus 56 sounding rocket, continuously monitoring and controlling the movement of the dust cloud inside the vacuum chamber. For this, ICAPS employed and tested a novel approach, the thermal trap. It consists of four rings that are fitted with heating elements to keep the cloud centered using thermophoresis. The data from two overview cameras with perpendicular fields of view is used as a reference for the thermal trap. An exemplary image of the cloud can be found on the left hand side of the below figure. The right hand side shows an agglomerate as seen by the on-board long distance microscope and captured by a high speed camera.

However, the main focus of this session lies on the scientific results. Within the first two minutes, the silica grains grew to agglomerates of around 103-104 constituent particles via hit-and-stick collisions. The analysis revealed insight into their collision speed, rate of growth and fractal dimension. Also, the influence of their charge could be studied because at several stages of the experiment an electric field was applied. In particular, it was possible to reconstruct some particles in three dimensions by linear displacement through the focal plane of the long distance microscope using the thermal trap. With these findings, it will be possible to classify the growth processes at play.

How to cite: Schubert, B., Blum, J., Molinski, N., Vedernikov, A., Balapanov, D., von Borstel, I., Rüffert, L., Aktas, C., Schräpler, R., and Westermeier, M.: ICAPS Sounding Rocket - Particle Growth, Europlanet Science Congress 2020, online, 21 Sep–9 Oct 2020, EPSC2020-567, https://doi.org/10.5194/epsc2020-567, 2020.

The role of magnetic fields in the evolution and dispersal of protoplanetary disks remains unclear to date partially due to the uncertainty regarding the sources of ionisation present in protoplanetary disks. Magnetic fields can only influence protoplanetary disk dynamics if the disks are sufficiently ionised. Ionisation due to X-rays, FUV photons and radioactivity is well-studied and generally only leads to high levels of ionisation close to the young star and in the surface layers of protoplanetary disks due to high disk column densities. Here I will instead focus on the importance of stellar cosmic rays which may provide a source of ionisation for the outer regions, and closer to the midplane, of protoplanetary disks.

Young solar-type stars are very magnetically active and drive stronger stellar winds in comparison to the present day Sun. The increased magnetic activity of young solar-type stars suggests that they are efficient ~GeV particle accelerators producing so-called stellar cosmic rays. Thus, protoplanetary disks are likely to be bombarded by stellar cosmic rays, influencing their chemical and dynamic evolution. These incident particles are believed to trigger the formation of complex organic molecules. Thus, they are essential to advance our understanding of how organic molecules, the building blocks of life in the Universe, form.

Recent ALMA observations have provided a number of tantalising clues as to the possible importance of stellar cosmic rays in protoplanetary disks. On the one hand, chemical modelling of observations of TW Hya’s protoplanetary disk suggest that the overall ionisation rate is remarkably low. While on the other hand, ALMA observations have been used to infer the presence of significant turbulent motion in DM Tau’s protoplanetary disk. This turbulent motion is likely driven by the magneto-rotational instability which would require a much higher level of ionisation than was inferred in TW Hya’s disk for instance. I will discuss the potential influence of stellar cosmic rays in these disks.

More generally, I will present recent results which investigated the propagation, and ionising effect, of stellar cosmic rays in protoplanetary disks around young solar-mass stars. Unlike X-rays and FUV photons, stellar cosmic rays may effectively avoid being attenuated by the high column densities in the inner regions of protoplanetary disks due to their diffusive transport. To construct our disk density profiles, we use observationally inferred values from nearby star-forming regions for the total disk mass and the radial density profile. By varying the disk mass within the observed scatter for a solar-mass star, we find for a large range of disk masses and density profiles that protoplanetary disks are “optically thin” to low energy stellar cosmic rays. I will describe how our results indicate, for a wide range of disk masses, that low energy stellar cosmic rays provide an important source of ionisation at the disk midplane at large radii (∼70 au). Finally, I will discuss the type of systems where we expect that stellar cosmic rays are likely to be most influential.

How to cite: Rodgers-Lee, D., Taylor, A., Downes, T., and Ray, T.: The role of stellar cosmic rays in protoplanetary disk evolution, Europlanet Science Congress 2020, online, 21 Sep–9 Oct 2020, EPSC2020-20, https://doi.org/10.5194/epsc2020-20, 2020.

There is growing observational evidence that giant planet formation happens early, within a million years of the coalescence of the protoplanetary disk. Ionization rate is one of the most important parameters controlling both the chemical and dynamical processes in these disks. What few observational constrains on ionization currently exists suggest overall low ionization, limiting the processes able to take place. This is seemingly in conflict with chemical models which demonstrate the importance of ionization for the chemical processing of volatile carbon and observations which suggest such processing is ubiquitous and happens quickly. I will present new NOEMA observations which, when combined with chemical modeling, are indicative of enhanced ionization rates in the envelopes of three Class I protostars. I will then discuss the potential impact of this early enhancement on the chemical composition of the material available to forming planets.

How to cite: Schwarz, K., Maret, S., Lefevre, C., Andre, P., Belloche, A., Bergin, E., and Codella, C.: Evidence of Enhanced Ionization During Early Planet Formation, Europlanet Science Congress 2020, online, 21 Sep–9 Oct 2020, EPSC2020-361, https://doi.org/10.5194/epsc2020-361, 2020.

I will present a demographic study of the gas content in protoplanetary disks of the Lupus star-forming region, based on the previous ALMA surveys of the region.

Planets form around stars during their pre-main sequence phase, when still surrounded by a circumstellar disk of dust and gas. Setting observational constraints on the gas and dust properties of protoplanetary disks is crucial in order to understand what are the ongoing physical processes in the disk. These processes shape the planet formation mechanisms, and ultimately tell us about the disk’s ability to form planets.

The advent of ALMA allowed us to characterize dust properties in large populations of disks in several star-forming regions. Nevertheless, demographic studies of the gas content in these disk populations are scarce and generally incomplete, due to the fewer detections, and other difficulties when studying gas content.

In this work, we were able to assemble a large and homogeneous sample of disks from the Lupus region, all detected in 12CO and dust continuum. Gas emission profiles and sizes are estimated on 43 disks of the Lupus region. The profiles are inferred from the integrated emission maps of the 12CO transition line in ALMA Band 6. The observed emission is modeled using empirical functions: either the Nuker profile or an elliptical Gaussian for more compact sources. The gas size, defined as a certain fraction (e.g. 68%) of the total flux, is inferred from the modeled emission profiles.

These gas properties are then compared to the dust properties of the same objects, estimated from ALMA surveys in Band 7 and using analogous methodology.

The relative size of gas and dust is a key diagnostic of dust evolution. Large dust grains are decoupled from gas and drift inwards. Thus, if dust growth is prominent in these disks, the detected dust continuum emission in sub-mm wavelengths are expected to be several times smaller than the gas extent.

The results of our extensive sample confirm the larger gas size when compared to the dust size. The gas disk size is on average 2.6 times larger than the dust disk. This size difference can be explained by effective drifting of dust, but also by the optical depth difference between 12CO and dust continuum. Disentangling between these two effects is in general difficult; only large size ratios (typically beyond 4) unequivocally exhibit prominent dust evolution.

Only a small fraction (~18%) of the disk population has a size ratio larger than 4. Radial drift is intimately linked to grain growth, both are crucial processes to form the cores of planets. Our results might suggest that dust evolution is less common than previously thought.

We also investigated possible trends of the size ratio with stellar and disk properties, e.g. stellar mass, disk mass, integrated CO flux; no clear correlation can be found. Interestingly, the only Brown Dwarf of the sample with characterized gas and dust disk sizes shows a relatively large ratio of 3.8. On the other stellar mass range end, disks around stars with mass > 0.8 Msun have a tentative lower ratio of 2.1. Larger samples in the low mass regime and in the rest of stellar mass ranges are needed in order to discern possible trends between spectral types or other properties of the host stars.

How to cite: Sanchis, E.: Gas extent in protoplanetary disks of the Lupus star forming region, Europlanet Science Congress 2020, online, 21 Sep–9 Oct 2020, EPSC2020-803, https://doi.org/10.5194/epsc2020-803, 2020.

What is the initial reservoir of mass available for making planets? This key question for planet formation got even more relevant when the measured masses of the Class II disks (1-3 Myr old) were found consistently smaller than what is needed for the formation of gas giant cores. One way to solve this conundrum is to investigate whether the disks at the younger stages contain enough dust. Should planets be formed earlier, in the first 0.5 Myr, the physical conditions and chemical composition assumed of the beginning of planet formation needs to be revised.

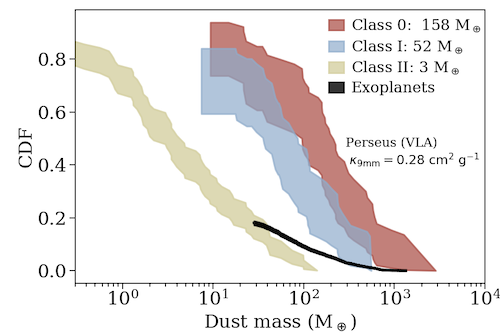

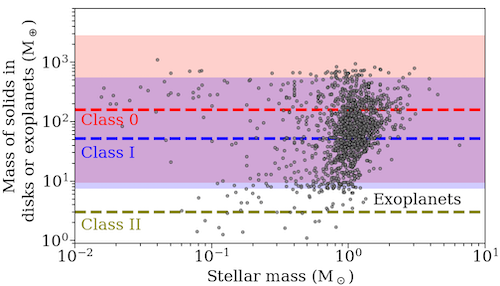

We use Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array (ALMA) observations of embedded disks in Perseus molecular cloud together with existing Very Large Array (VLA) data to provide a robust estimate of disk masses and to compare the Perseus survey of dust masses with other ALMA surveys of young and mature disks. The combination of the two interferometric facilities observing at different wavelengths enables detailed characterization of the dust emission from young disks. Our best estimate of the median dust disk masses is 158 M⊕ (Earth masses) and 50 M⊕, for Class 0 and Class I respectively. These values are much higher than the median found typically in Class II disks (~5 M⊕) (Fig. 1). In Fig. 2 we show that the masses typically found in exoplanetary systems are well in a range of masses available in Class 0 and Class I.

We put the improved disk mass estimates in the context of masses of known exoplanetary systems. The masses of Class 0 and I disks in Perseus can produce the observed exoplanet systems with efficiencies acceptable by planet formation models. The most massive observed exoplanets can still be produced by the most massive Class 0 disks with an efficiency of 15%, higher efficiencies on the order of 30% are needed if the planet formation starts in Class I. Interestingly, we find that most massive exoplanetary systems require higher efficiencies. (Fig. 1, right).

Our results are most consistent with the starting point of the planet formation already in the Class 0 stage, first 0.1 Myr after the beginning of the star and disk formation process. This has major implications for the physical and chemical conditions of the formation of extrasolar planets and of our own Solar System.

Fig. 1. Cumulative distribution function of dust disk masses and solid content of exoplanets. Top: Cumulative distribution function of dust masses for Class 0 (red) and Class I (blue) disks in Perseus and Class II disks (yellow) in Lupus measured with ALMA (Ansdell et al. 2016). In black, the masses of the exoplanet systems are normalized to the fraction of the gaseous planets (Cumming et al. 2008). Perseus disk masses calculated with κ9mm=0.28 cm2g−1 from the VLA fluxes. Medians are indicated in the labels. Bottom: Zoom-in to the ranges where exoplanets are present. The color scale shows the efficiency needed for the planet formation for a given bin of the distribution.

Fig. 2. Plot showing the distribution of masses of exoplanetary systems obtained from the exoplanet.eu catalog (Schneider et al. 2011), for planets around main-sequence stars with the measured masses. Shaded areas mark the range of our best estimation of the dust disk masses in Perseus: Class 0 (red) and Class I (blue) calculated from the VLA fluxes with the opacity value of κ9mm=0.28 cm2g−1. Medians of the distributions, 158 and 52 M⊕, for Class 0 and I, respectively, are indicated with the dashed lines. The median mass of the Class II disks in Lupus, 3 M⊕ (Ansdell et al. 2016) is shown in yellow. The masses of the solids in exoplanetary systems are plotted against the stellar mass of the host star. All planets with available information on the mass are included in this plot.

How to cite: Tychoniec, Ł., Manara, C., Rosotti, G., van Dishoeck, E., Cridland, A., Hsieh, T.-H., Murillo, N., Segura-Cox, D., van Terwisga, S., and Tobin, J.: Dust masses of young disks: constraining the initial solid reservoir for planet formation, Europlanet Science Congress 2020, online, 21 Sep–9 Oct 2020, EPSC2020-850, https://doi.org/10.5194/epsc2020-850, 2020.

Abstract

The evolution of millimeter-sized dust in a protoplanetary disk is one of the key observable constrains on the formation of planets. In recent years, ALMA surveys of disks in nearby star-forming regions have shown a dependence of the disk mass distribution on cloud properties and environmental factors. Due to the relatively small number of regions for which these statistics are available, several key questions have so far been out of reach for observers: do disk masses vary across clouds, or are they constant? How far does the influence of massive young stars reach in different environments? How do the masses of Class II-disks compare to those of embedded objects?

We present new results from the Survey of Orion Disks with ALMA (SODA), based on observations of 882 disks in the southern part of the Orion A molecular cloud. This flux-limited survey is the largest of its kind so far, and spans a large area on the sky with multiple young groups and clusters, as shown in Figure 1. We find that disk properties across the cloud are remarkably uniform, between clusters and between regions of different stellar density. However, the presence of B-stars is significant.

Introduction

Different ALMA surveys in individual star forming regions have significantly improved our understanding of the evolution of protoplanetary disks in recent times. In particular, most of the nearby low-mass star-forming regions (SFRs) have now been observed at mm-wavelengths, as well as several SFRs hosting massive stars (e.g., Ansdell et al. 2016, Pascucci et al. 2016, Eisner et al. 2018, van Terwisga et al. 2020). These studies have provided key insight in how circumstellar matter evolves as planetary systems take shape.

Observations so far have shown that disks of all masses evolve rapidy within the first few Myr of their existence (Tychoniec et al. 2020). In addition to these age effects, the disk mass distribution of populations of disks in strongly irradiated environments has also been shown to be subject to external photoevaporation. Disks decrease in mass in stronger radiation fields in regions like σ Ori and the Trapezium (Ansdell et al. 2017, Mann et al. 2014, Eisner et al. 2018), demonstrating the direct impact of extreme environments on disk evolution. Model predictions (from

e.g. the FRIED grid, by Haworth et al. 2018) and observations of individual disks in low-mass SFRs have shown that even in an environment like Taurus, where the UV radiation is a factor 1000 weaker than in the Trapezium, half of the disks undergo significant mass loss.

A key problem is that even with the current state-of-the-art data, the number of different star-forming regions sampled is quite small. Additionally, even in regions where complete surveys of the Class II population exist, like Lupus, stars exist in a range of environmental conditions. Our survey of Orion A, the largest of its kind so far, covers large numbers of disks in a wide variety of environments, allowing us to link disk properties to their enviroment more firmly than before.

Figure 1: The 882 Class II YSOs targeted in this survey (green plus signs), and groups and clusters identified by Megeath et al. 2016 (pink crosses). The background shows the total gas and dust column as derived from Herschel continuum maps (Lombardi et al. 2014).

Data reduction

Our observations cover a large number of sources at low (1.4'') resolution in ALMA Band 6. This resolution is low compared to the expected disk structure. This meant we could use a high-performance computing cluster to reduce and image the data in a fraction of the time it would otherwise take, simulateously guaranteeing consistent and reproducible results.

Results

Figure 2: Disk mass distribution in the SODA sample, compared to several other well-studied nearby star-forming regions.

By converting disk fluxes to masses we can compare the properties of the Orion A disks sample, both within different regions of Orion A, and between Orion A and other clouds, like Lupus and Taurus, which have been surveyed previously. As Figure 2 shows, the large number of disks in our sample allows us to determine the disk mass distribution much more accurately than previously possible. However, the large sample size also enables us to compare average disk masses between regions in Orion A, as shown in Figure 3, which shows that there are only small differences in average disk masses between areas of vastly different surface densities, even across the length of the cloud, and emphasizes the remarkable similarity between disks in Orion, Taurus, and Lupus. However, the presence of nearby B-stars is relevant for disk masses, out to scales of several parsecs, a parameter range that it was not previously possible to probe.

Figure 3: Disk masses as a function of density of YSOs, across Orion A, and in Lupus, show a remarkable similarity across many orders of magnitude.

How to cite: van Terwisga, S., Hacar, A., and van Dishoeck, E.: Losing weight with SODA: the impact of environment on disk properties in Orion A, Europlanet Science Congress 2020, online, 21 Sep–9 Oct 2020, EPSC2020-1098, https://doi.org/10.5194/epsc2020-1098, 2020.

The role of the pre-solar chemistry in the chemical composition of Solar System bodies is far to be understood. Did they inherit at least part of their composition from the earliest stages of star formation? During each step of the process leading to the formation of a Sun-like star and its planetary system, the molecular complexity increases from simple species up to interstellar Complex Organic Molecules (iCOMs, O-, N-, S-bearing species whit at least 6 atoms). In turn, iCOMs can be considered as bricks that can be used to assemble pre-biotic molecules. In this context, the study of the molecular complexity of Class 0 objects, where protostars are still deeply embedded in their parental core and still accreting their mass, is mandatory. As a matter of fact, protostellar radiation heats the surrounding medium creating the so-called hot-corinos, i.e. the regions of about 100 au with temperatures of at least 100 K, hot enough to (i) evaporate dust mantles, and (ii) trigger a warm gas phase-chemistry. As a consequence, the iCOMs abundances bloom, dramatically enriching the gas phase. The chemistry of the protostellar environments represents the first stage, and it needs to be compared with those of more evolved phase including relics of our pristine Solar System, such as comets.

The investigation of star-forming regions has enormously benefited from the recent advent of the IRAM-NOEMA and ALMA (sub-) mm-interferometers, which allowed the observers to reach Solar System scales. It is of paramount importance to combine high-sensitivity spectral surveys to collect large numbers of lines for each iCOM (for reliable identifications and to analyse excitation conditions) as well as to image their spatial distribution to investigate their association with different ingredients of the Sun-like star formation recipe (e.g. warm envelopes and cavities opened from hot jets, accretion disks, disk winds). The overall goal is to analyse the protostellar disk, i.e. the region where a Solar System will form billions of years later. The imaging of these regions with molecules simpler than iCOMs, such as CO or CS is indeed paradoxically hampered by their high abundances and consequently high line opacities which do not allow the observers to disentangle all the emitting components at these small scales.

In this respect, we will report recent results of a prototypical object such as IRAS4A, showing how complementing images obtained in the cm-spectral regime are to mimimise iCOMs emission hampering due to dust opacity. Finally, we will focus on the protostellar disk HH212, observed with a spatial resolution down to about 10 au. A large number of iCOMs, such as CH3OH, CH3CHO, HCOOCH3, CH3CH2OH, NH2CHO, have been imaged: their emission is clearly associated with the upper and lower rings in the outer part of the disk imaged using continuum emission. Indeed, the geometry of these features has led this source to be called a “space hamburger” in the popular press. We will discuss the possible explanations: (i) the disk has a vertically extended gaseous atmosphere (the “methanol buns”) and no gaseous methanol on the disk midplane (the “dusty meat”); (ii) the optically-thick disk midplane obscures iCOMs’ emission. The answer is essential to understand the gas composition in the equatorial plane, where planets will form.

How to cite: Codella, C., Ceccarelli, C., Lee, C.-F., De Simone, M., Bianchi, E., Podio, L., and Mercimek, S.: Complex organics in protostellar disks: the first stage of a long chemical journey to planetary systems , Europlanet Science Congress 2020, online, 21 Sep–9 Oct 2020, EPSC2020-288, https://doi.org/10.5194/epsc2020-288, 2020.

Understanding how molecular complexity varies in Sun-like star forming regions is mandatory to comprehend whether the chemical composition of the protostellar stages is inherited by protoplanetary disks and planets. In this perspective, our ambitious overall goal is to follow the chemical evolution from the earliest protostellar stages to the relics of our pristin Solar System, i.e. comets. We investigate the chemical composition of Class I protostars, with a typical age of 105 yr. Class I sources represent a bridge between Class 0 protostars (about 104 yr), where the bulk of the material that eventually form the protostar is still in the envelope, and the Class II protoplanetary disks (106 yr). The importance of the Class I stage has been recently strengthened by recent ALMA images showing that planet formation occurs already in disks with ages < 1 Myr. Unfortunately, only very few Class I sources, e.g. SVS13-A and Ser-17, have been chemically characterized through spectral survey at millimeter wavelengths. Therefore, we are still far to conclude if Class I protostars are also a bridge from a chemical point of view.

In this context, and in the framework of the H2020 MSCA ITN Project AstroChemical Origins (www.aco-itn.org), we present a chemical census of 4 Class I sources: L1551-IRS5, L1489-IRS (in the Taurus star forming region) and B5-IRS1, L1455-IRS1 (in Perseus). We used IRAM 30m single-dish observations at 1.3 mm sampling spatial scales of 1500-2500 au. We detect up to 80 lines (depending on the source) due to 27 species: from simple molecules (e.g. S-bearing: OCS, H2S, CCS, H2CS, N-bearing: CN, HNCO, C-chains: c-C3H2, c-C3H, D-species: CCD, DCN, D2CO, CH2DOH, ions: N2D+, DCO+) to the so called interstellar Complex Organic Molecules (iCOMs), which can be considered as the bricks of a prebiotic chemistry (H2CO, H2CCO, CH3OH, CH3CN, CH3CHO, CH3CCH, HCOOCH3).

All the sources are associated with high-velocity CO, H2CO, and SO outflows. In addition, our observations show a chemical differentiation, that can be summarized as follows: (1) we detect hot corino chemistry in one source, L1551 -IRS5, revealed by iCOMs as well as OCS, H2S, which could be the main S-bearing carriers on icy grains; (2) the envelopes of all the protostars are rich of carbon-chains molecules; (3) we find that the iCOMs of L1551 have similar abundance ratio, within one order of magnitude, as Class 0 and Class I hot corinos previously observed.

We also compare the iCOMs abundance ratios as measured in the Class I source L1551-IRS5 with those measured in comets Hale-Bopp, Lemmon, Lovejoy, and 67P to understand if the cometary composition is inherited from the previous evolutionary stages. We find that the iCOMs abundance ratio (e.g. CH3CHO/HCOOCH3) at the Class 0 and Class I protostellar stages is comparable with that of comets, suggesting that cometary material could be inherited from the early stages of the star forming process leading to a Sun-like star. These results are a basis to future follow-up interferometric observations aimed to obtain a full inventory of the chemistry of Class I sources and to reconstruct the chemical route from Class 0 protostars to protoplanetary disks and planets.

How to cite: Mercimek, S., Codella, C., Podio, L., Bianchi, E., Chahine, L., Lòpez-Sepulcre, A., Neri, R., and Ceccarelli, C.: Chemical inventory of Class I protostars with IRAM-30m: A bridge between protostars and planet-forming disks, Europlanet Science Congress 2020, online, 21 Sep–9 Oct 2020, EPSC2020-326, https://doi.org/10.5194/epsc2020-326, 2020.

Detection of hot corinos in Solar-like protostars has been so far mostly limited to Class 0 objects, hampering our understanding of their origin and evolution. Recent evidence suggests that planet formation probably starts already in Class I protostars, representing a key step in our understanding of their chemical composition at the planet formation scale. Therefore, understanding the fate of hot corinos in Class I protostars has become of paramount importance. In this context, we report the discovery of a hot corino at the heart of the prototypical Class I source L1551 IRS5, obtained via ALMA observations as part of the Large Program FAUST (Fifty AU Study of the chemistry in the disk/envelope system of Solar-like protostars). More specifically, FAUST is the first ALMA Large Program based on astrochemistry and is designed to survey the chemical composition of a sample of 13 Class 0 and I protostars at the planet-formation scale.

We detected in L1551 IRS 5 several emission lines from interstellar complex organic molecules (iCOMs) such as methanol and its most abundant isotopologues, as well as methyl formate and ethanol. The line emission is bright toward the north component (N), although a hot corino in the south component, cannot be excluded. The non-LTE analysis of the methanol lines towards N provides constraints on the gas temperature (~ 100 K), density (≥ 1.5 x 108 cm-3) and emitting size (~0.15”, i.e. ~ 10 au in radius). The lines are predicted to be optically thick, the 13CH3OH line having an opacity ≥ 2. The methyl formate and ethanol column densities relative to methanol are ≤ 0.03 and ≤ 0.015, respectively, compatible with those measured in Class 0 sources. Thus, the present observations towards L1551 IRS5 agree with little chemical evolution in hot corinos from Class 0 to I.

How to cite: Bianchi, E., Yamamoto, S., Ceccarelli, C., Chandler, C., Codella, C., and Sakai, N. and the FAUST Team: Fifty AU Study of the chemistry in the disk/envelope system of Solar-like protostars (FAUST) Large program first results: the hot corino in L1551 IRS5, Europlanet Science Congress 2020, online, 21 Sep–9 Oct 2020, EPSC2020-603, https://doi.org/10.5194/epsc2020-603, 2020.

We performed a deep search for CCS, SO, SO2, OCS, H2S, H2CS and other molecules in the DM Tau

protoplanetary disk at 2mm with PolyFiX@NOEMA. With a beam of ~2''x1'' and a spectral resolution of 0.3 km/s,

a high sensitivity of ~3.8 mJy/beam was achieved. We detected o-H2S, o-H2CS, and DNC (first time in DM Tau)

as well as H13CO+, N2D+, and, tentatively, HC3N. We have not detected SO2, our main target molecule. We used the

non-LTE radiative transfer code RADEX to derive disk-averaged column densities and their upper limits. These values,

together with our previous ALMA CS data were used for disk chemical modeling. The presence of CS and the lack of

SO2 in the DM Tau disk molecular layer can only be reliably explained by the disk model with a non-solar gas-phase C/O ratio

of ~1, supporting previous findings.

How to cite: Semenov, D., Favre, C., Fedele, D., Teague, R., Dutrey, A., Guilloteau, S., Henning, T., and Smirnov-Pinchukov, G.: The power of PolyFiX at NOEMA: new insights into sulfur chemistry in DM Tau, Europlanet Science Congress 2020, online, 21 Sep–9 Oct 2020, EPSC2020-304, https://doi.org/10.5194/epsc2020-304, 2020.

PDS 70 is the only disk known to date that hosts two massive planets clearing a large cavity in the dust distribution. The planets have been detected in both infrared and Halpha, indicating that they are still actively accreting from the planet-hosting environment. The elemental composition of the growing planetary atmospheres are bound to be related to the composition of the accreting material. Bright molecular lines of simple chemical species can be used to infer chemical properties of the material that is being accreted by the planets (as C/O and C/N ratios), as well as physical processes presently occurring in the disk (shocking of gas onto the circumplanetary disks, ionisation). In this talk, I will show new ALMA band 6 observations of PDS 70 at moderate angular resolution in two spectral settings targeting HCN and CO isotopologues, small hydrocarbons, H2CO, H13CO+ and simple S bearing molecules. The molecular emission is particularly bright, with 15 molecular lines detected and imaged. The radial and azimuthal structures of the different molecules provide unique information on the chemical and physical conditions of PDS 70.

How to cite: Facchini, S.: Chemical inventory of a planet hosting disk, Europlanet Science Congress 2020, online, 21 Sep–9 Oct 2020, EPSC2020-796, https://doi.org/10.5194/epsc2020-796, 2020.

One of the main goals in the fields of exoplanets and planet formation is to determine the composition of terrestrial, potentially habitable, planets and to link this to the composition of protoplanetary disks. A longstanding puzzle in this regard is the Earth's severe carbon deficit; Earth is 2-4 orders of magnitude depleted in carbon compared to interstellar grains and comets. The solution to this conundrum is that carbon must have been returned to the gas phase in the inner protosolar nebula, such that it could not get accreted onto the forming bodies. A process that could be responsible is the sublimation of carbon grains at the so-called soot line (~300 K) early in the planet-formation process. I will argue that the most likely signatures of this process are an excess of hydrocarbons and nitriles inside the soot line around protostars, and a higher excitation temperature for these molecules compared to oxygen-bearing complex organics that desorb around the water snowline (~100 K). Moreover, I will show that such characteristics have indeed been reported in the literature, for example, in Orion KL, although not uniformly, potentially due to differences in observational settings or related to the episodic nature of protostellar accretion. If this process is active, this would mean that there is an heretofore unrecognized component to the carbon chemistry during the protostellar phase that is acting from the top down - starting from the destruction of larger species - instead of from the bottom up from atoms. In the presence of such a top-down component, the origin of organic molecules needs to be re-explored.

How to cite: van 't Hoff, M., Bergin, E., Jorgensen, J., and Blake, G.: Carbon-grain sublimation: a new top-down component to protostellar chemistry, Europlanet Science Congress 2020, online, 21 Sep–9 Oct 2020, EPSC2020-960, https://doi.org/10.5194/epsc2020-960, 2020.

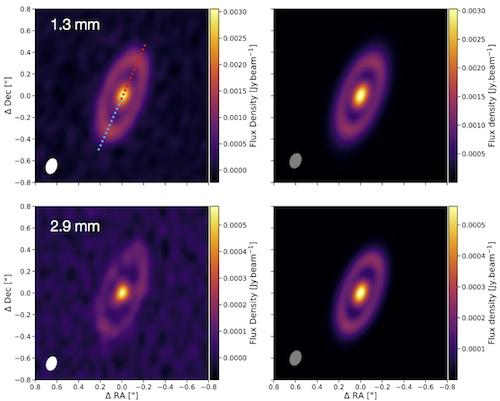

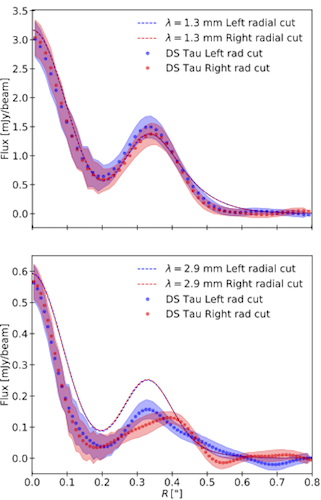

Recent high resolution and high fidelity observations of protoplanetary discs are showing us peculiar substructures such as spirals, gaps, rings and horseshoes. In particular recent surveys have shown that the majority of these discs are characterised by rings and gaps. What can we learn from these features? Are these discs hiding planets? I will present the results we have obtained in order to model one specific disc orbiting around DS Tau, an M-type star, in the Taurus star-forming region located at a distance of 159 pc. This disc is showing a wide gap (∼30 au) in the continuum at 1.3 mm (Long et al. 2018) and at 2.9 mm (Long et al. 2020) (left panels of Fig. 1).

We performed 3D-hydrodynamical (PHANTOM, Price et al. 2018) and radiative transfer (MCFOST, Pinte et al. 2006, 2009) simulations in order to reproduce the observed gap shape at 1.3 mm. In this modeling, we assumed that the observed gap is carved by a planet between one and five Jupiter masses. We fit the shape of the radial intensity profile along the disc major axis varying the planet mass, the dust disc mass, and the evolution time of the system. In the central panels of Fig. 1 we show the synthetic images, that have been computed for our best fit model (performed on the 1.3 mm case) parameters: Mp=3.5 MJup, Mdust=9.6*10-5 Msun and t=145 orbits. The right panels compare radial cuts of the flux intensity profile along the disc major axis obtained from the synthetic image at 1.3 and 2.9 mm (top and bottom center panel of Fig. 1) with the ALMA data (top and bottom left panel). The left (blue) and right (red) side of the radial cut correspond to the left and right side of the disc major axis. Dot markers represent the data, while the models are in dashed lines.

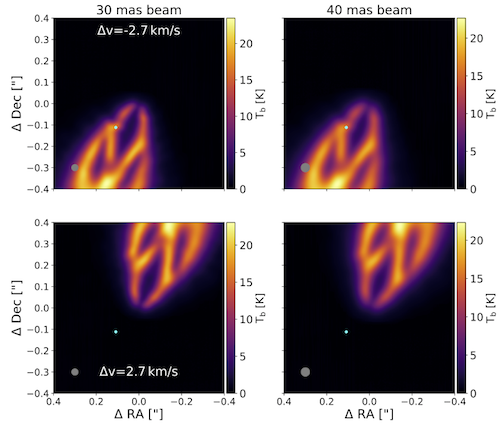

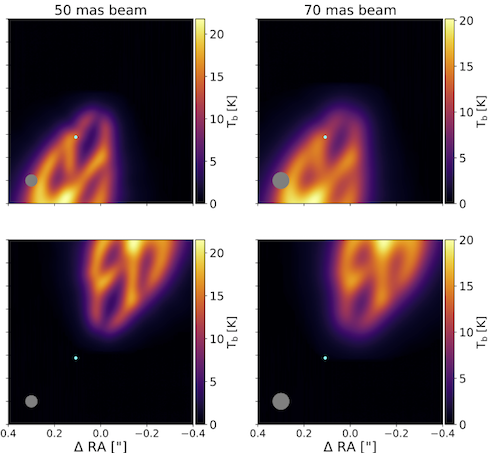

We also computed the CO-isotopologues channel maps for the best model fitting the dust continuum (see Fig. 2 for an example), in order to study the expected signature of the planet in the gas kinematics.

We found that the planet mass fitting the ALMA image is 3.5 Mjup and that this planet would be able to produce a kink detectable by ALMA with a reasonable beam size and velocity resolution.

Figure 1. First row: ALMA observation (left panel) and continuum mock image (center panel) of the DS Tau disc at 1.3 mm. The synthetic image has been computed for our best fit model Mp=3.5 MJup and Mdust=9.6*10-5 Msun). The Gaussian beam we take to convolve the full resolution image has been chosen to reproduce the observations reported by Long et al. (2018) and Long et al. (2020), respectively 0.14''x0.1'' and 0.13''x0.09''. In the 1.3 mm image we highlight in blue the left side of the major axis and in red the right side. Right panel shows the comparison between the left (blue) - right (red) side of the radial cut along the disc major axis for the data (dot marker) and the modeling (dashed line). Second row: Same as first row but for the 2.9 mm continuum image.

Figure 2: Channel maps for C18O isotopologue with a velocity resolution of 0.2 km/s and a beam size of [30,40,50,70] mas (from left to right). The azimuthal position of the planet is φ=225°. We show two velocity channels, Δv=2.7 km/s, where a kink is visible, and the opposite one at Δv=-2.7 km/s.

How to cite: Veronesi, B., Ragusa, E., Lodato, G., Aly, H., Pinte, C., Price, D. J., Long, F., Herczeg, G. J., and Christiaens, V.: Is the DS Tau disc hiding a planet?, Europlanet Science Congress 2020, online, 21 Sep–9 Oct 2020, EPSC2020-398, https://doi.org/10.5194/epsc2020-398, 2020.

New instruments such as the ALMA interferometer and SPHERE on VLT allowed to obtain a large number of high-resolution images of protoplanetary discs. In these images, substructures such as gaps and rings can be clearly resolved and appear to be very common (see eg. Andrews et al. 2018).

A natural explanation for the origin of such structures is the dynamical interaction of the gas and dust in the disc with one or more planets embedded in the parental disc (e.g. Lin & Papaloizou 1979, Dipierro et al. 2015, Rosotti et al. 2017, ..). Detections of planets embedded in disks are rare (e.g. Quanz et al. 2013, Keppler et al. 2018) and are mostly related to giant planets at wide orbits. However, the observed structures can be due to the interaction between the disc and low-mass planets.

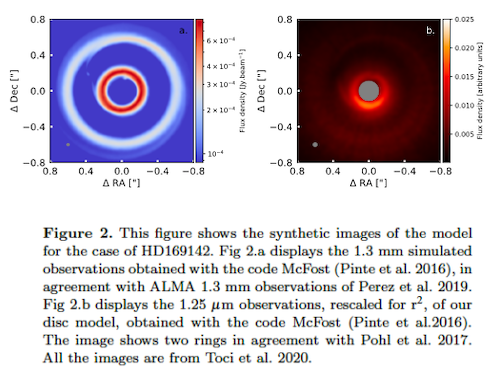

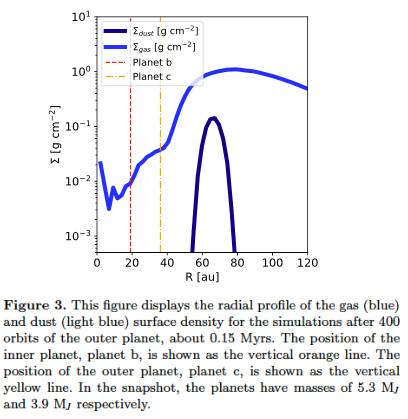

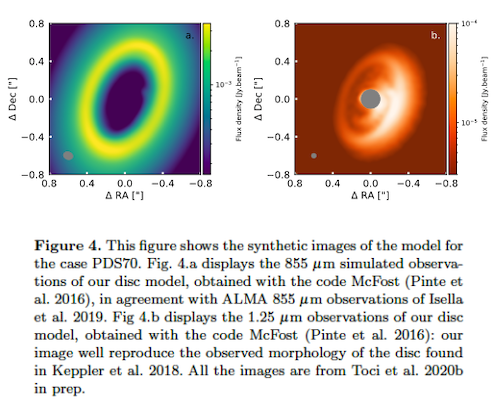

Planet-disc interaction can be studied with a synergy between observational results, current theoretical model and numerical simulations. In particular, theoretical models can find “signatures” to spot the presence of planets in discs, such as dusty or gaseous features due to the presence of circumplanetary discs or accretion streams (Bae et al. 2019, Toci et al. 2020) to be compared with real observations (Isella et al. 2019). I will present an analysis of several 3D SPH numerical simulations devised to analyze planet-disc interaction in presence of two giant planets.

I will then compare my results with two observed systems: (1) HD169142 (Fedele et al.2017, Perez et al. 2019), a well studied source with two prominent rings in dust and gas; (2) PDS 70, the first source where protoplanets have been directly observed (Keppler et al. 2018). We initialise the system containing two giant planets in the disc (hereafter planet b and planet c respectively), studying the initial conditions that lead to the formation of a cavity in the gas distribution and rings in the dust. I will present the results about the dynamics of these discs (gap width, ring size and shape, cavity shape) and the properties of the planets (Toci et al., ApJL 2020, Toci et al. 2020, in prep.). My results show that the presence of two giant planets in a 5:1 resonance can be responsible of a long-lived dust ring between them, while at the same time creating a large gas cavity. However, the dust ring is absent when the giant planets end up in a closer resonance (3:1 or 2:1). I will also show how important it is to consider the migration and the accretion of planets for modelling observational results.

Indeed, the interaction between the planets and the disc can give signatures both in the dust and gas components, leading to detectable features. In particular, our results suggest that the spur in the observed 1.3 mm continuum images of Perez et al. 2019 can be due to the interaction between the inner giant and the inner dust ring (see Fig. 1 and Fig. 2). If so, the spur should move according to the orbital motion of the planet. This theoretical prediction will be testable in a few years with new ALMA observations. Similarly, in the case of PDS70, the structures observed in Keppler et al. 2018 and Isella et al. 2019 can be explained with an accretion stream from the disc to the planet and the presence of a dusty circumplanetary disc (see Fig. 3 and Fig. 4).

How to cite: Toci, C., Lodato, G., Fedele, D., Testi, L., Pinte, C., Christiaens, V., and Price, D. J.: Dynamics of giant planets in protoplanetary discs, Europlanet Science Congress 2020, online, 21 Sep–9 Oct 2020, EPSC2020-438, https://doi.org/10.5194/epsc2020-438, 2020.

High-resolution imaging of protoplanetary discs has revealed their wealth of substructure. Perhaps the most striking observation has been the presence of large-scale crescent-shaped features, which have been interpreted as large quantities of dust trapped in anticyclonic vortices. Such regions of high dust-to-gas ratios are expected to promote planet formation processes, so understanding their formation and evolution is of primary interest.

Gas-only hydrodynamics simulations have demonstrated that the thermal feedback from a planetary embryo undergoing rapid formation by pebble accretion can trigger the generation a large-scale vortex. However, the ability for such a vortex to trap dust and the impact this has on the forming planet are yet to be investigated. I will present results from hydrodynamics simulations of a disc containing both gas and dust, showing the efficiency with which dust grains accumulate in a vortex, and discuss the consequences this has for the growth of the planetary embryo.

How to cite: Cummins, D. and Owen, J.: Planet Formation in Transition Discs, Europlanet Science Congress 2020, online, 21 Sep–9 Oct 2020, EPSC2020-765, https://doi.org/10.5194/epsc2020-765, 2020.

Ringed protoplanetary disks, in the Class II phase of low-mass star formation when the envelope has mostly dispersed, have been found in abundance in recent years with high-resolution ALMA observations. These ringed disks have been often interpreted as evidence of ongoing planet formation. In the younger Class 0 and I phases there are few examples of high resolution dust disk observations due to the challenge of the dense envelope surrounding the disk, and more often than not reveal spiral-like structures. However, these embedded stages may be when the first steps of planet formation occur, and studying ringed structures in these phases will constrain the initial conditions of planet formation. We have used ALMA 1.3 mm long-baseline dust continuum observations to study the Class I protostar IRS 63 with 7 au resolution and expose the detailed physical structure of a Class I disk. The ALMA data indicate that concentric dust rings are present in the disk, revealing IRS 63 is the youngest-known protostellar disk with multiple ringed dust substructures and demonstrating that these features are already present in the Class I phase. The dust ring structures could arise via several mechanisms including rapid pebble growth near snowlines, magnetorotational instabilities, asymmetric accretion from the envelope to disk, or planet-disk interactions carving gaps in the disk. Even if planets have not yet formed, dust rings in disks at such an early evolutionary stage could provide a stable environment for long enough time scales to grow planets.

How to cite: Segura-Cox, D.: Rings in a Young Embedded Disk: Footholds of Planet Formation at Early Times, Europlanet Science Congress 2020, online, 21 Sep–9 Oct 2020, EPSC2020-1071, https://doi.org/10.5194/epsc2020-1071, 2020.

Phosphorus is one of the most important elements in biochemistry together with carbon, oxygen, hydrogen and nitrogen. Therefore, P-bearing compounds with some prebiotic potential and their possible formation pathways in extraterrestrial environments are attracting a lot of interest.

In recent years, phosphorus has been clearly identified in the in the coma of comet 67P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko (1), while only a bunch of P-bearing molecules (namely PO, PN, CP, C2P and HCP) have been observed in the gas phase of circumstellar envelopes around evolved stars (2-7) and only two simple species have been detected in star forming regions, that is, PO and PN (8-11). If we focus only on solar-type star forming regions, only two detections are available, that is PN and PO toward the shocked region L1157-B1 (12) and the Class I protostar B1-b (13). Phosphorus chemistry in the conditions of the interstellar medium is poorly understood and the interstellar reservoir of this element is strongly debated. Since the first experimental work on ion-molecule reactions by Anicich and coworkers (14), PO has been indicated as the main reservoir of phosphorus and HPO+ as its major precursor. PO can also be transformed to PN by gas-phase chemistry (15). Thirty years ago, a series of theoretical investigation on ion-molecule reactions has been performed by Largo et al. (16-18) in order to explain the formation of P-O, P-N, P-C bonds. In spite of those efforts, the chemistry of interstellar phosphorus and its connections to the P-compounds detected in small bodies of the Solar System remains mostly unexplored and poorly characterized. For this reason, we have undertaken a systematic investigation of possible gas-phase formation routes of simple P-molecules by means of electronic structure and kinetic calculations. This approach is made necessary by the fact that P is a difficult species to deal with in laboratory experiments.

In this work we present a new theoretical analysis of the reaction P+ + H2O and P+ + NH3 at a higher level of theory than those employed by Largo et al. in 1991. More specifically, we make use of DFT calculations for geometry optimization and frequency analysis coupled to a CCSD(T) reevaluation of the energy for each identified stationary point of the reaction potential energy surface. The data coming from electronic structure calculations will be used to perform a kinetic analysis using a Rice-Ramsperger-Kassel-Marcus (RRKM) code implemented for this purpose in order to derive the rate coefficients and branching ratios. A possible formation mechanism is proposed for the formation of both PO and PN. In the figure, the potential energy surface for the reaction of P+ with a water molecule is reported. This process leads to the formation of the POH+ ion which can later transfer a proton to molecules like NH3 which have a large proton affinity.

[1] Altwegg K. et al., Prebiotic chemicals—amino acid and phosphorus—in the coma of comet 67P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko, Sci. Adv., 2016, 2 : e1600285.

[2] Turner, B. E. & Bally, J., Detection of Interstellar PN: The First Identified Phosphorus Compound in the Interstellar Medium, 1987, ApJL, 321, L75.

[3] Ziurys L.M., Detection of Interstellar PN: The First Phosphorus-bearing Species Observed in Molecular Clouds, 1987, ApJL, 321, L81.

[4] Guelin M. et al., Free CP in IRC +10216, 1990, ApJL, 230, L9-L11.

[5] Agúndez M. et al., Discovery of Phosphaethyne (HCP) in Space: Phosphorus Chemistry in Circumstellar Envelopes, APJ, 662, ApJ, 2, L91-L94.

[6] Tenenbaum E.D. et al., Identification of Phosphorus Monoxide (X2Πr) in VY Canis Majoris: Detection of the First PO Bond in Space, 2007, ApJ, 666, 1, L29-L32.

[7] Halfen D.T. et al.,Detection of the CCP Radical (X2Πr) in IRC +10216: A New Interstellar Phosphorus-containing Species, 2008, ApJL, 667, 2, L101.

[8] Rivilla V.M. et al., Phosphorus-bearing molecules in the Galactic Center, 2018, MNRAS, 475, 1, L30-L34.

[9] Rivilla V.M et al., ALMA and ROSINA detections of phosphorus-bearing molecules: the interstellar thread between star-forming regions and comets, 2020, MNRAS, 492, 1, 1180-1198.

[10] Rivilla V.M., The first detections of the key prebiotic molecule PO in star-forming regions, 2018, IAU Symposium, 332, 409-414.

[11] Rivilla V.M., The First Detections of the Key Prebiotic Molecule PO in Star-forming Regions, 2016, ApJ, 826, 2, 161.

[12] Lefloch B. et al., Phosphorus-bearing molecules in solar-type star-forming regions: first PO detection, 2016, MNRAS 462, 3937–3944.

[13] Bergner J.B. et al., Detection of Phosphorus-bearing Molecules toward a Solar-type Protostar, 2019, The ApJ Lett., 884, 2, L36.

[14] Thorne L.R et al., The chemistry of Phosphorus in Dense Interstellar Clouds, 1984, ApJ, 280, 139-143.

[15] Millar T.J. et al., An efficient gas phase synthesis for interstellar PN, 1987, Mon. Not. R. Aster. Soc., 229, 41-44.

[16] Largo A. et al., Theoretical Studies of Possible Processes for the Interstellar Production of Phosphorus Compounds. Reaction of P+ with Water, 1991, J. Phys. Chem., 95, 5443-5445.

[17] Largo A. et al., Theoretical Sttudies of Possible Processes for the Interstellar Production of Phosphorus Compounds. Reaction of P+ with Methane, 1991, J. Phys. Chem., 95, 6553-6557.

[18] Largo A. et al., Theoretical Sttudies of Possible Processes for the Interstellar Production of Phosphorus Compounds. Reaction of P+ with Ammonia, 1991, J. Phys. Chem., 95, 170-175.

How to cite: Mancini, L., Rosi, M., Balucani, N., Skouteris, D., Codella, C., and Ceccarelli, C.: Probing the Chemistry of P-Bearing Molecules in Interstellar Environments and other Extraterrestrial Environments, Europlanet Science Congress 2020, online, 21 Sep–9 Oct 2020, EPSC2020-643, https://doi.org/10.5194/epsc2020-643, 2020.

Cyanopolyynes are a family of carbon-chain molecules that have been detected in numerous objects of the interstellar medium (ISM), such as hot cores, star forming regions and cold clouds [1–4]. The simplest cyanopolyyne, HC3N, has been among the first organic molecules to be observed in the ISM [5] and up to date also HC5N, HC7N, HC9N and HC11N have been detected [6, 7]. HC3N and HC5N are also abundant in solar-type protostars (see for instance a recent work on IRAS 16293-2422 by Jaber Al-Edhari et al. [8]). Remarkably, HC3N has also been detected in comet C/1995 O1 (Hale-Bopp) and, together with other organic molecules, could be a part of the legacy of interstellar organic chemistry to the newly formed solar systems [9,10].

Cyanoacetylene has been suggested as an important brick in chain elongation processes, via its reaction with the C2H radical producing HC5N. Its reaction with the CN radical, instead, results in a chain termination reaction with the formation of dicyanoacetylene, NC-CC-CN (C4N2). Dicyanoacetylene and higher dicyanopolyynes have not been observed in the ISM so far because they lack a permanent electric dipole moment and cannot be detected through their rotational spectrum. However, it has been suggested that they are abundant in interstellar and circumstellar clouds [11] and account for a significant fraction of the total carbon budget. The reaction between CN radical and cyanoacetylene is also believed to be the main source of C4N2, an observed species in the upper atmosphere of Titan, the massive moon of Saturn [12].

To characterize the chemistry of cyanoacetylene in various extraterrestrial environments, in our laboratory, we have undertaken a systematic investigation of the reactions involving cyanoacetylene and atomic or diatomic radicals which are relatively abundant in space. The investigated reactions include CN + HC3N, O+HC3N and N+HC3N. We have used a sophisticated experimental technique to investigate these reactive systems under single collision conditions in order to be able to establish the nature of the primary products and their branching ratio without ambiguity (for some details see [13]). In addition, we have performed dedicated electronic structure and kinetic calculations to derive the relevant parameters to be included in astrochemical models. Implications for the chemistry of interstellar objects as well as the chemistry of cometary comae and the upper atmosphere of Titan will be noted.

This project has received funding from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under the Marie Sklodowska Curie grant agreement No 811312 for the project ”Astro-Chemical Origins”.

[1] Wyrowski, F., Schilke, P., Walmsley, C.: Vibrationally excited HC3N toward hot cores. Astronomy and Astrophysics 341 (1999) 882–895

[2] Taniguchi, K., Saito, M., Sridharan, T., Minamidani, T.: Survey observations to study chemical evolution from high-mass starless cores to high-mass protostellar objects I: HC3N and HC5N. The Astrophysical Journal 854(2) (2018) 133

[3] Mendoza, E., Lefloch, B., Ceccarelli, C., Kahane, C., Jaber, A., Podio, L., Benedettini, M., Codella, C., Viti, S., Jimenez-Serra, I., et al.: A search for cyanopolyynes in L1157-B1. Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society 475(4) (2018) 5501–5512

[4] Takano, S., Masuda, A., Hirahara, Y., Suzuki, H., Ohishi, M., Ishikawa, S.i., Kaifu, N., Kasai, Y., Kawaguchi, K., Wilson, T.: Observations of 13C isotopomers of HC3N and HC5N in TMC-1: evidence for isotopic fractionation. Astronomy and Astrophysics 329 (1998) 1156–1169

[5] Turner, B.E.: Detection of interstellar cyanoacetylene. The Astrophysical Journal 163 (1971) L35–L39

[6] Broten, N.W., Oka, T., Avery, L.W., MacLeod, J.M., Kroto, H.W.: The detection of HC9N in interstellar space. 223 (July 1978) L105–L107

[7] Bell, M., Feldman, P., Travers, M., McCarthy, M., Gottlieb, C., Thaddeus, P.: Detection of HC11N in the cold dust cloud TMC-1. The Astrophysical Journal Letters 483(1) (1997) L61–L64

[8] Jaber Al-Edhari, A., Ceccarelli, C., Kahane, C., Viti, S., Balucani, N., Caux, E., Faure, A., Lefloch, B., Lique, F., Mendoza, E., Quenard, D., Wiesenfeld, L.: History of the solar-type protostar IRAS 16293-2422 as told by the cyanopolyynes. A&A 597 (2017) A40

[9] Mumma, M.J., Charnley, S.B. The Chemical Composition of Comets—Emerging Taxonomies and Natal Heritage. Annu. Rev. Astron. Astrophys. 49 (2011) 471–524

[10] Bockelée-Morvan, D., Lis, D. C., Wink, J. E., Despois, D., Crovisier, J., Bachiller, R., et al. New molecules found in comet C/1995 O1 (Hale-Bopp). Investigating the link between cometary and interstellar material.

A&A 353 (2000) 1101

[11] Petrie, S., Millar, T., Markwick, A.: NCCN in TMC-1 and IRC+ 10216. Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society 341(2) (2003) 609–616

[12] Petrie, S., Osamura, Y.: NCCN and NCCCCN formation in titan’s atmosphere: 2. HNC as a viable precursor. The Journal of Physical Chemistry A 108 (2004) 3623–3631

[13] Casavecchia, P., Leonori, L., Balucani, N. Reaction dynamics of oxygen atoms with unsaturated hydrocarbons from crossed molecular beam studies: primary products, branching ratios and role of intersystem crossing. Int. Rev. Phys. Chem. 34 (2015) 161-204

How to cite: Liang, P., Valença Ferreira de Aragão, E., Faginas-Lago, N., Vanuzzo, G., Recio, P., Marchione, D., Tan, Y., Rosi, M., Mancini, L., Skouteris, D., Casavecchia, P., and Balucani, N.: Cyanoacetylene gas-phase chemistry of relevance in interstellar objects, comets and other bodies of the Solar System: a combined experimental and theoretical investigation, Europlanet Science Congress 2020, online, 21 Sep–9 Oct 2020, EPSC2020-700, https://doi.org/10.5194/epsc2020-700, 2020.

Introduction:

Charged species have been detected at various stages of stellar evolution, from pre- and protostellar objects to planet-forming disks, where they can be used as signatures of the build-up in chemical complexity [1, 2, 3, 4, 5]. On the other hand, on planets and planetary bodies with atmospheres exposed to photons and energetic particles, ionic reactions have been suggested as playing a significant role in the build-up of chemical complexity. A good example is the atmosphere of Titan, where the CASSINI mission [6] detected, by mass spectrometry, a wide range of N-containing organic ions, and photochemical models [7, 8] predict that these ions trigger a rich gas-phase chemistry, eventually forming tholins, a key ingredient of Titan’s haze [9]. Similar effects may be expected in the atmospheres of exoplanets, for which simulation experiments indicate that complex photochemistry can take place leading to formation of large molecules [10, 11]. It has been suggested that complex organic molecules (COMs) could be synthesised through reactions on dust grains, a process which might be facilitated by the acceleration of cations in the gas phase towards negatively charged dust grains [12]. It is therefore important to understand the gas-phase ion chemistry of these environments in order to develop reliable chemical models.

Results:

In our laboratories, we measure kinetic parameters (cross sections, branching ratios and their dependences on collision energy) for the reaction of charged molecules with neutrals, using tandem mass spectrometric techniques and RF octupolar trapping of parent and product ions.

In this contribution, we examine the reactions of two isomers of [CNH3]+ that are believed to contribute to the m/z 29 peak observed in the aforementioned mass spectra of Titan’s atmosphere, namely HCNH2+ and H2CNH+, with a range of neutrals including both saturated; CH4; and unsaturated; C2H2, C2H4, C3H4 (allene), C3H4 (propyne) and C3H6; hydrocarbons as well as some simple nitriles; CH3CN and C2H3CN; and CH3OH with the objective of identifying the reaction pathways present as well as their respective rate constants and branching ratios.

Experimental Methods: The data presented here for the HCNH2+ and H2CNH+ ions were collected using the CERISES instrument attached to the DESIRS beamline of the French SOLEIL synchrotron [13], using VUV photons to generate ions through either direct photoionization or dissociative photoionization of suitable neutral precursors. The HCNH2+ ion was generated exclusively through dissociative photoionization of cyclopropylamine (C3H7N)[14] while H2CNH+ was generated both through dissociative photoionization of azetidine (C3H7N also) and via direct photoionization of neutral methanimine, produced via a gas-solid reaction between aminoacetonitrile in gas phase and powdered potassium hydroxide [15]. Working in this way allows us to present data as a function of the energy of the photons used in the ionisation; which in the case of direct ionisation is a proxy for the internal energy of the ions; as well as as a function of the collision energy. Ab initio calculations have also been performed for some of these reactions, with work underway on the others, in order to aid the interpretation of the mechanisms involved in the formation of the various products and their respective energy profiles.

Conclusions: Our experiments demonstrate that not only can the two isomers of [CNH3]+ be generated selectively, but that they show wide-ranging and varied chemistries with a wide range of different neutral molecules. In addition to undergoing charge transfer, proton-transfer and H-abstraction reactions, these isomers also appear to undergo a range of more complex pathways proceeding via the adduct, demonstrating that these species could indeed play a role in the complex gas-phase chemistry of planetary atmospheres with C and N-containing species.

Acknowledgements: D.A. and V.R. acknowledge funding from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under the Marie Skłodowska-Curie grant agreement No 811312 for the project "Astro-Chemical Origins” (ACO). We acknowledge SOLEIL for provision of synchrotron radiation facilities and the DESIRS beamline team for their assistance, and J-CG would like to thank the Centre National d’Etudes Spatiales (CNES) for their financial support.

[1] L. Podio et al., A&A, 565, A64 (2014)

[2] C. Vastel et al. , A&A, 591, L2 (2016)

[3] A. Bacmann et al. , A&A, 588, L8 (2016)

[4] N. Marcelino et al. , A&A, 612, L10 (2018)

[5] V.M. Rivilla et al. , MNRAS Lett. , 483, L114 (2019)

[6] V. Vuitton , R.V. Yelle and M.J. McEwan, Icarus, 191, 722-742 (2007)

[7] V. Vuitton et al., Icarus, 324, 120-197 (2019)

[8] S.M. Horst, J. Geophys. Res. Planets, 122, 432-482 (2017)

[9] D. Dubois et al. , ApJ Lett, 872, L31

[10] C. He, S.M. Hörst et al. , ACS Earth Space Chem. , 3, 39-50 (2019)

[11] J. Bourgalais et al. , ApJ, 897 (77), 13pp (2020)

[12] C.R. Stark, C. Helling, D.A. Diver and P.B. Rimmer, Int. J. Astrobiology, 13 (2), 165-172 (2014)

[13] D. Ascenzi et al. , Frontiers in Chemistry, 7, 537 (2019)

[14] J. Chamot-Rooke, P. Mourgues et al. , Int. J. Mass Spectrom., 226, 249-269 (2003)

[15] J.C. Guillemin et al. , Tetrahedron, 44, 4431-4446 (1988)

How to cite: Richardson, V., Alcaraz, C., Geppert, W., Guillemin, J.-C., Polášek, M., Romanzin, C., Sundelin, D., Thissen, R., Tosi, P., and Ascenzi, D.: Building chemical complexity with ion-molecule reactions: from protostellar stages to Solar System planets and exoplanets, Europlanet Science Congress 2020, online, 21 Sep–9 Oct 2020, EPSC2020-736, https://doi.org/10.5194/epsc2020-736, 2020.

Please decide on your access

Please use the buttons below to download the presentation materials or to visit the external website where the presentation is linked. Regarding the external link, please note that Copernicus Meetings cannot accept any liability for the content and the website you will visit.

Forward to presentation link

You are going to open an external link to the presentation as indicated by the authors. Copernicus Meetings cannot accept any liability for the content and the website you will visit.

We are sorry, but presentations are only available for users who registered for the conference. Thank you.