Oral presentations and abstracts

The exploration of the outer solar system by Galileo at Jupiter, Cassini-Huygens at Saturn, and New Horizons at Pluto-Charon, has revealed that several icy worlds harbor a subsurface salty ocean underneath their cold icy surface. By flying through the icy-vapor plume erupting from Enceladus' south pole, Cassini proceeded for the first time to the analysis of fresh materials coming from an extraterrestrial ocean, revealing its astrobiological potentials. Even if there is no direct evidence yet, similar oceanic habitats might also be present within Europa, Ganymede and Titan, which will be characterized by future missions currently under development for the exploration of icy Galilean moons (JUICE, Europa Clipper) and of Saturn’s moon Titan (Dragonfly).

Understanding these icy ocean worlds and their connections with smaller icy moons and rings requires input from a variety of scientific disciplines: planetary geology and geophysics, atmospheric physics, life sciences, magnetospheric environment, space weathering, as well as supporting laboratory studies, numerical simulations, preparatory studies for future missions and technology developments in instrumentation and engineering. We welcome abstracts that span this full breadth of disciplines required for the characterization and future exploration of icy worlds and ring system.

Session assets

Icy bodies are the most numerous and diverse bodies in the Solar System, but only a few have been visited or will be visited by a space probe. The Galilean satellites are one of those, especially Ganymede which is the primary target of the future L-class mission JUICE (launch scheduled in 2022) in ESA’s Cosmic Vision programme. Ganymede's surface visually exhibits an important geological diversity, with young bright areas to older dark terrains. This diversity also expresses itself through the moon’s surface composition, which was studied extensively in situ by the NIMS instrument of the Galileo mission (NASA) in the late 90s; like the majority of giant planet satellites, Ganymede's surface is dominated by H2O-ice and some non-icy components, very likely hydrated salts based on the distorted shape of the spectral signatures (McCord et al., 2001). However, this binary composition has been obtained with a spectral sampling (~25 µm) not allowing to detect specific absorptions for the non-icy materials, thus not allowing their identification. Hence, many questions about Ganymede’s surface composition remain unanswered while important technical advances have been made since.

In preparation of the JUICE mission, and specifically of the near-infrared imaging spectrometer MAJIS of the JUICE mission, a ground-based campaign was performed using an instrument with a much finer, i.e. better, spectral sampling: SINFONI (SINgle Faint Object Near-IR Investigation). SINFONI is installed on the UT4 of the Very Large Telescope (VLT hereafter) at the European Southern Observatory (ESO hereafter) in Chile. It combines one adaptive optics module and an integral field spectrometer operating in the near-infrared covering from the beginning of the J-band (~1.1 µm) to the end of the K-band (~2.45 µm). Here we present the results derived from the analysis and the modeling of four observations acquired at different dates, from October 2012 to March 2015, all covering the 1.45 – 2.45 µm wavelength range with a spectral resolution about 0.5 µm and a spatial sampling of 12.5 x 12.5 mas2. These results were recently published in Icarus (Ligier et al., 2019).

The first result we obtained concerns the physical properties of Ganymede’s surface. Indeed, the data reduction process highlights that the Lambertian model is not sufficient to remove the photometric effects due to observations geometry. Instead, the Oren-Nayar model (Oren & Nayar, 1994), which generalizes the Lambertian law for rough surfaces, produces excellent results where no inclination residuals are observed up to inclination angles around 65°. The quality of the photometric correction is thus used as proxy to infer Ganymede’s surface roughness: from 16° ± 6° to 21° ± 6° depending on the observations.

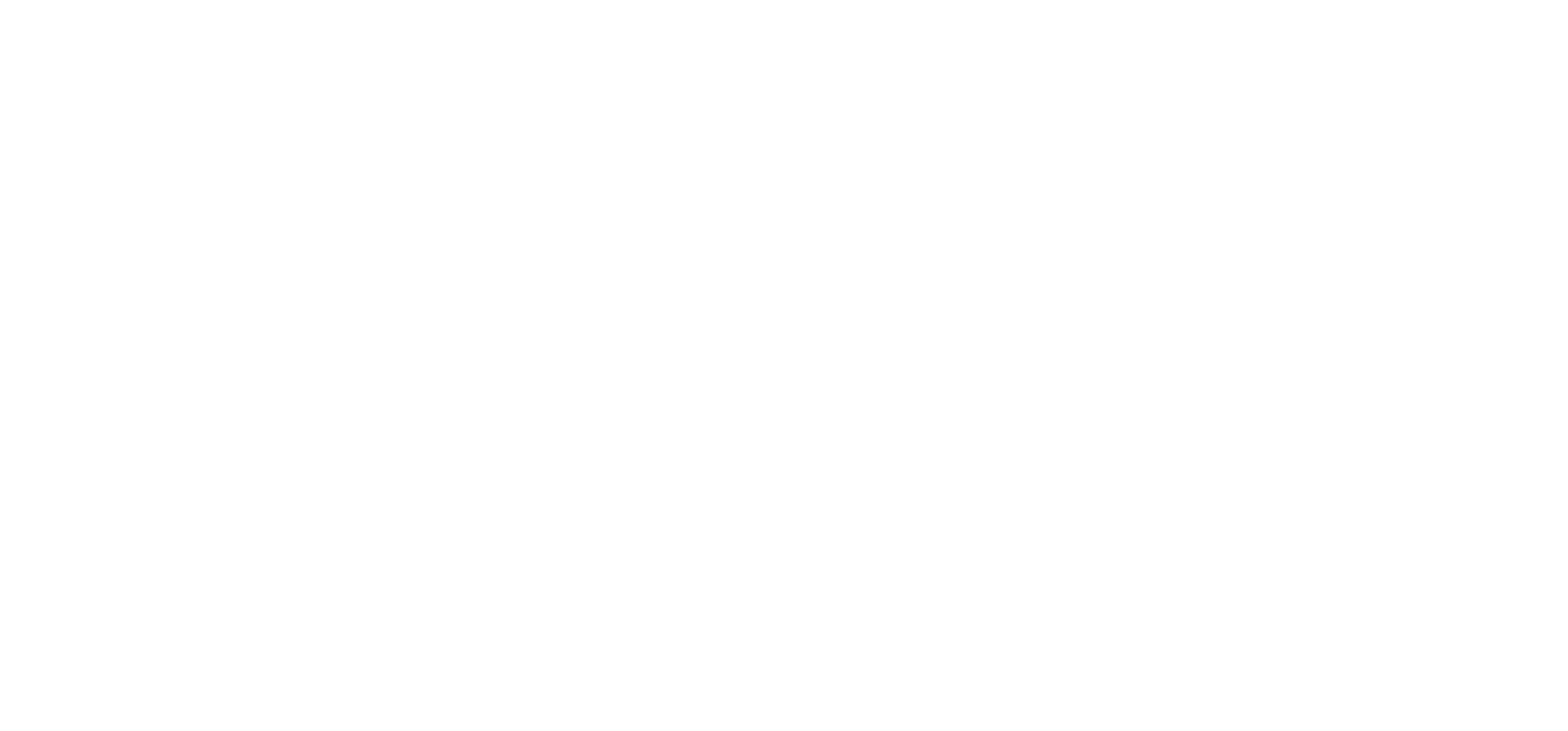

Then, concerning the surface composition of the moon, our modeling confirms that it is dominated by H2O-ice, predominantly the crystalline form. The abundance maps of the ice show two main patterns: (1) a latitudinal gradient in terms of abundance, with large polar caps, and (2) a latitudinal gradient in terms of grain size, where the smaller grains (>50 µm) are located at the highest latitudes, showing a sharp transition around ±35°N coinciding with the transition between open and closed field lines of Ganymede’s own magnetic field (figure 1a). Ice sublimation explains this distribution, redistributing H2O-ice from the “hot” equator to the colder poles, very likely redeposited as finer grains.

Apart from the ice, another major compound is required to fit Ganymede’s spectra: a darkening agent. Similarly to previous studies, this darkening agent could not be identified, but we were able to provide new constraints on it. First of all, this unknown material cannot be organic matter since its reflectance level, about 0.25, is more or less five times higher than that of organic matter. Instead, the reflectance level suggests a silicate-type material, as already mentioned in a previous study about Callisto (Calvin & Clark, 1991). Its abundance map shows the highest abundances (up to 0.85) at equatorial latitudes in the trailing hemisphere (figure 1b). The well-known surface sputtering engendered by Jupiter’s magnetosphere is the simplest process to explain such distribution. Even with the magnetic field of the moon, it is possible for corotating singly-charged ions to become neutralized near the moon and continue to the surface as neutrals, sputtering mostly around the trailing apex.

Last but not least, our study highlights the necessity of secondary species, i.e. >10% overall, to better fit the measurements: sulfuric acid hydrate and salts, likely sulfates and chlorinated. While the sulfuric acid hydrate is, like H2O-ice, mostly located at high latitudes (figure 1c), the abundance map of the salts shows a heterogeneous distribution which seems neither related to the Jovian magnetospheric bombardment nor craters (figure 1d). These species are mostly detected on bright grooved terrains surrounding darker areas. Endogenous processes, such as freezing of upwelling fluids going through the moon’s ice shell, may explain this heterogeneous distribution.

How to cite: Ligier, N., Paranicas, C., Carter, J., Poulet, F., Calvin, W., Nordheim, T. A., and Snodgrass, C.: Pending the JUICE/ESA mission … surface composition and properties of Ganymede from near-infrared ground-based measurements, Europlanet Science Congress 2020, online, 21 Sep–9 Oct 2020, EPSC2020-655, https://doi.org/10.5194/epsc2020-655, 2020.

Abstract

While the thickness of Europa’s ice shell is underconstrained by the current knowledge of the body, it is not unconstrained. That is, while there are many possible ice shell thicknesses, not all are equally plausible. In this study, I survey the current knowledge of Europa and quantify distributions in the parameters and processes that control ice shell thickness. I then create a Monte Carlo simulation of 107 plausible Europa’s with ice shells in thermodynamic equilibrium, and condition the result into a probability distribution for ice shell thickness. I predict a best estimate thickness of 22.0 km, but with great uncertainty. These results may inform future planning and inferences from NASA’s Europa Clipper mission and ESA’s JUICE mission later this decade [1].

Introduction

Within its predominantly water-ice shell, Jupiter’s moon Europa likely harbors a global saltwater ocean, placing it among an emerging class of celestial objects known as Ocean Worlds. The ice shell is thought to consist of a brittle upper lithosphere, where heat transfer occurs by thermal conduction, and a ductile interior asthenosphere that may be convecting in solid-state. The icy surface of this shell exhibits one of the youngest average ages in the solar system (~40 – 90 Myr) [2], requiring the recent or current geologic resurfacing.

The geologic processes within the ice shell responsible for the young surface may convey material between the surface and interior ocean, critically influencing chemical disequilibria within the watery interior and the habitability of Europa’s ocean [3], [4]. However, the thickness of the ice shell and therefore the potential for geologic material exchange is unknown, and estimates span three order of magnitude.

Following discoveries at Europa by the Galileo mission, a summary of ice shell thickness predictions was made by Billings and Kattenhorn [5], providing a name to the “Great Thickness Debate.” That study catalogued dozens of previous publications, collating estimates for icy thicknesses from a few hundred meters to many tens of kilometers.

In order to estimate a probability distribution for Europa’s ice shell thickness using the Monte Carlo method, several parameters must be estimated. Therefore, I first identify current best estimate (CBE) values and construct distributions that capture the uncertainty in those values for several key parameters. In each instance, I determine both the range of values for the parameter of interest and the form of the probability distribution for that parameter.

Method

Assuming an ice shell in thermodynamic equilibrium, the heat flux out of the icy lithosphere radiated to space is equal to the heat flux into the base of the lithosphere from the silicate interior plus the internal heat generated by tidal dissipation within a ductile convecting asthenosphere, integrated over the depth of the asthenosphere.

For each of these terms, I identify the underlaying uncertainties associated with their calculation. For Europa as a whole, I include uncertainties in total H2O layer and iron core thickness. In the silicate interior, I consider uncertainties in radiogenic heating associated with the material Europa accreted from, as well as the potential for silicate tidal dissipation based on mechanical constraints. For the ice shell, I consider uncertainties in convective and melting temperatures, grain size, empirical diffusion creep constants, non-ice composition, porosity, mechanical properties, and tidal response.

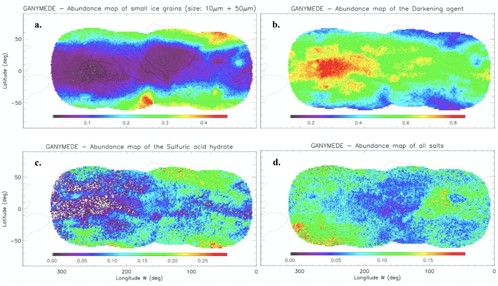

The thickness of the conductive and convective layer are then sampled according to the governing equations for heat transfer and tidal heat dissipation (Figure 1).

Results and Discussion

The CBE ice shell thickness for Europa is 22.0 km (Figure 2), though the spread in potential thicknesses is great. Only ~1% of possible configurations are thinner than 15 km, and the median thickness is ~40 km. Further, ice shells are primarily dominated by heat transfer through thermal conduction (Figure 3), with thermal convection being relegated most commonly to the bottom 1/3rd or less of the ice shell.

I will address several surprising results in the underlaying distributions, and their affect on the overall solution. Additionally, there are many key sensitivities built in to this model that may be retired through future laboratory analysis and spacecraft observation. In parallel, some unresolvable issues will persist until the ice shell is explored in situ.

Figures

Figure 1. Differential and cumulative probability distributions for Europa’s ice shell thickness. The steep rise is attributed to the inverse relationship between minimum ice shell thickness and total heat flux, and the tail to the right is controlled by silicate heat flux and H2O thickness.

Figure 2. Probability heat map showing conductive and convective thicknesses. Warmer colors denote higher probability. White dashed lines show lines of constant ice shell thickness. Note, for example, that the red line showing a constant thickness of 15 km falls outside the majority of solutions, while the line showing 20 km thickness passes through regions of high probability.

Acknowledgements

This work was performed at the Jet Propulsion Laboratory, California Institute of Technology, under contract with the National Aeronautics and Space Administration.

References

[1] S. M. Howell and R. T. Pappalardo, “NASA’s Europa Clipper—a mission to a potentially habitable ocean world,” Nat. Commun., vol. 11, no. 1, Art. no. 1, Mar. 2020, doi: 10.1038/s41467-020-15160-9.

[2] E. B. Bierhaus, K. Zahnle, C. R. Chapman, R. T. Pappalardo, W. R. McKinnon, and K. K. Khurana, “Europa’s crater distributions and surface ages,” Europa, pp. 161–180, 2009.

[3] K. P. Hand, C. F. Chyba, J. C. Priscu, R. W. Carlson, and K. H. Nealson, “Astrobiology and the Potential for Life on Europa,” in Europa, R. T. Pappalardo, W. B. McKinnon, and K. Khurana, Eds. Tucson: University of Arizona Press, 2009, p. 589.

[4] S. M. Howell and R. T. Pappalardo, “Can Earth-like plate tectonics occur in ocean world ice shells?,” Icarus, 2019, doi: 10.1016/j.icarus.2019.01.011.

[5] S. E. Billings and S. A. Kattenhorn, “The great thickness debate: Ice shell thickness models for Europa and comparisons with estimates based on flexure at ridges,” Icarus, vol. 177, no. 2, pp. 397–412, Oct. 2005, doi: 10.1016/j.icarus.2005.03.013.

How to cite: Howell, S.: The Likely Thickness of Europa’s Icy Shell, Europlanet Science Congress 2020, online, 21 Sep–9 Oct 2020, EPSC2020-173, https://doi.org/10.5194/epsc2020-173, 2020.

JUICE - JUpiter ICy moons Explorer - is the first large mission in the ESA Cosmic Vision 2015-2025 programme. The mission was selected in May 2012, and entered in implementation phase “D” in March 2019. Due to launch in May 2022 and to arrive at Jupiter in October 2029, it will spend at least three ½ years making detailed observations of Jupiter and three of its largest moons, Ganymede, Callisto and Europa. The status of the project and the main milestones in 2020-2021 are presented.

Science Objectives

The focus of JUICE is to characterise the conditions that might have led to the emergence of habitable environments among the Jovian icy satellites, with special emphasis on the three worlds, Ganymede, Europa, and Callisto, likely hosting internal oceans. Ganymede, the largest moon in the Solar System, is identified as a high-priority target because it provides a unique and natural laboratory for analysis of the nature, evolution and potential habitability of icy worlds and waterworlds in general, but also because of the role it plays within the system of Galilean satellites, and its special magnetic and plasma interactions with the surrounding Jovian environment. The mission also focuses on characterising the diversity of coupling processes and exchanges in the Jupiter system that are responsible for the changes in surface and space environments at Ganymede, Europa and Callisto, from short-term to geological time scales. Focused studies of Jupiter’s atmosphere and magnetosphere, and their interaction with the Galilean satellites will further enhance our understanding of the evolution and dynamics of the Jovian system. The overarching theme for JUICE is the emergence of habitable worlds around gas giants. At Ganymede, the mission will characterize the ocean layer, provide topographical, geological and compositional mapping of the surface, study the physical properties of the icy crust, characterize the internal mass distribution, investigate the exosphere, study the intrinsic magnetic field and its interactions with the Jovian magnetosphere. At Europa, the focus will be on the surface composition, understanding the formation of surface features and subsurface sounding of the icy crust over recently active regions. Callisto will be explored as a witness of the early solar system, trying to elucidate the mystery of its internal structure. JUICE will also perform a multidisciplinary investigation of the Jupiter system as an archetype for gas giants. The Jovian atmosphere will be studied from the cloud top to the thermosphere. Concerning Jupiter’s magnetosphere, investigations of the three dimensional properties of the magnetodisc and of the coupling processes within the magnetosphere, ionosphere and thermosphere will be carried out. JUICE will study the moons’ interactions with the magnetosphere, gravitational coupling and long-term tidal evolution of the Galilean satellites.

The payload

The JUICE payload consists of 10 state-of-the-art instruments plus one experiment that uses the spacecraft telecommunication system with ground-based instruments. This payload is capable of addressing all of the mission's science goals, from in situ measurements of the plasma environment, to remote observations of the surface and interior of the three icy moons, Ganymede, Europa and Callisto, and of Jupiter’s atmosphere. A remote sensing package includes imaging (JANUS) and spectral-imaging capabilities from the ultraviolet to the sub-millimetre wavelengths (MAJIS, UVS, SWI). A geophysical package consists of a laser altimeter (GALA) and a radar sounder (RIME) for exploring the surface and subsurface of the moons, and a radio science experiment (3GM) to probe the atmospheres of Jupiter and its satellites and to perform measurements of the gravity fields. An in situ package comprises a powerful suite to study plasma and neutral gas environments (PEP) with remote sensing capabilities of energetic neutrals, a magnetometer (J-MAG) and a radio and plasma wave instrument (RPWI), including electric fields sensors and a Langmuir probe. An experiment (PRIDE) using ground-based Very Long Baseline Interferometry (VLBI) will support precise determination of the spacecraft state vector with the focus at improving the ephemeris of the Jovian system.

The mission profile

The mission is due to launch from Kourou with an Ariane 5 ECA. The baseline launch is 20 May 2022, with two backup launch slots in September 2022 and August 2023. The baseline interplanetary transfer sequence relies on gravity assist with Venus, the Earth and Mars. The Jupiter orbit insertion will be performed in October 2029. A Ganymede swing-by is performed just before the capture manoeuvre. The tour of the Jupiter system, as currently designed, starts with a series of three Ganymede swing-bys. The spacecraft is transferred to Callisto to initiate the Europa science phase, one year after the Jupiter insertion. This phase is composed of two fly-bys, separated by 15 days, with closest approach at 400 km altitude. The next phase is a 200-day period characterized by an excursion at moderate inclinations, in order to investigate regions of the Jupiter environment away from the equatorial plane. A series of resonant transfers with Callisto raise the inclination with respect to Jupiter’s equator to a maximum value of about 28 deg. The spacecraft is then transferred from Callisto to Ganymede with a series of Callisto and Ganymede flybys, followed by a gravitational capture with the moon. The orbital phase around Ganymede is split into a first elliptical subphase, a circular orbit at 5000 km altitude followed by another elliptical sub phase, and then a circular phase at 500 km altitude. The duration of the Ganymede phase is about nine months, the end of mission being planned in September 2033. The spacecraft will eventually impact the surface.

The key project milestones in 2020-2021

- February 2020: First instrument delivered

- May 2020: Interface test between the spacecraft engineering model and the mission operations centre

- Second quarter of 2020: Instrument deliveries and integration

- January 2021: Start of the environmental tests

- First half of 2021: Spacecraft tests

- November 2021: Flight acceptance review

How to cite: Witasse, O. and the JUICE Teams: JUICE (Jupiter Icy Moon Explorer): A European mission to explore the emergence of habitable worlds around gas giants, Europlanet Science Congress 2020, online, 21 Sep–9 Oct 2020, EPSC2020-76, https://doi.org/10.5194/epsc2020-76, 2020.

Abstract

It has long been postulated that Europa might have a sub-surface ocean covered by an icy crust. First clues for the existence of such a sub-surface ocean were obtained by the Galileo magnetometer in the late '90s [1]. If such an ocean indeed exists, it might sporadically erupt in plumes. Indeed, in 2014, [2] reported on increased Lyman-α and oxygen OI130.4 nm emissions, which the authors interpreted as transient water vapor measurements resembling water plumes. In this presentation we analyze different plume models to determine which model would result in an observation as the one presented by [2], and analyze what implications this might have for the upcoming measurements of the Neutral and Ion Mass spectrometer (NIM) onboard JUICE.

1. Plume observations

[2] characterized the source of the increased Lyman-α and oxygen OI130.4 nm emissions through modeling. According to their results, the emissions are best described by two individual water vapor plumes that are located at 90°W/55°S and 90°W/75°S, respectively, both of which exhibit a radial expansion of ~200 km and a latitudinal expansion of ~270 km, and the surface densities of which amount to 1.3x1015 m-3 and 2.2x1015 m-3, respectively.

2. Plume model

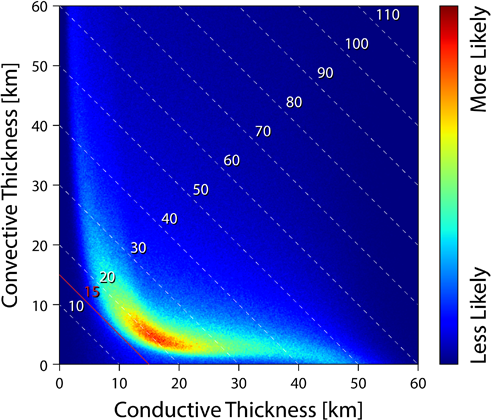

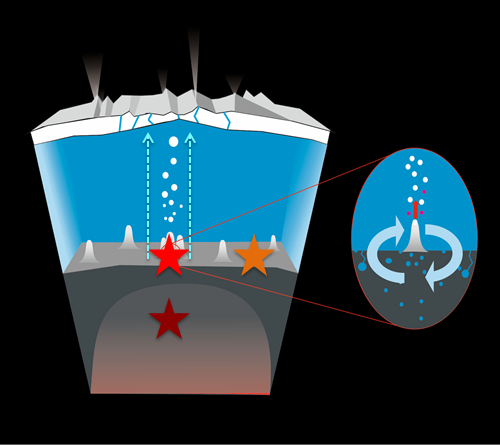

The source of the observed plume might either be a liquid or a solid (icy) reservoir that evaporates or sublimates as it comes into contact with space. Figure 1 shows different scenarios which could lead to the localized release of H2O particles resulting in a plume-like structure. In the first scenario, a surface, or near-surface, liquid reservoir is exposed to near-vacuum conditions upon which water directly evaporates into space. In the second scenario, a crack in the ice shell all the way to the bottom leads to the exposure of oceanic water to space, resulting in the formation of an oceanic plume. If the flow is chocked (by the conduit's geometry), the plume may become a supersonic jet. In the third scenario a rising diapir results in the warming of local surface ice (indicated by the shaded region in Figure 1), which sublimates into space. The water temperature was set to 280 K in scenarios one and two, whereas the ice temperature was set to 250 K in scenario three, and the reservoir areas were set to ~1'000 m2 and ~20'000 m2, respectively.

Figure 1: The three analyzed scenarios: Scenario one shows evaporation of a surface, or near-surface, liquid, scenario two shows evaporation of oceanic water (in form of a jet), and scenario three shows the sublimation of surface ice heated by diapirs.

3. Monte-Carlo Model

To simulate Europa's plumes, we use a 3D Monte Carlo model originally developed to model Mercury's exosphere [3]. In this model particles are created ab initio, travel on collision-less trajectories, and are removed as they are either ionized, fragmented, or lost either to space or by freezing out on the surface. The grids are ~25x25x25 km3 in size, thus almost a factor 10 higher in resolution than the [2] measurements. For comparison with the [2] observations we also merged our model results into 200x200x200 km3 bins.

4. Model Results

Figure 2 shows our model results for the three different scenarios presented above. For each scenario, we present the [2] measurement on the left, the reduced resolution result in the middle, and the high resolution result on the right. All measurements are normalized to one and span six orders of magnitude.

Figure 2: Model results for the three analyzed scenarios. The top row shows the surface liquid scenario, the middle row shows the oceanic water jet scenario, and the bottom row shows the diapir scenario. The [2] measurement is shown on the left, the reduced resolution model results are shown in the middle, and the high resolution model results are shown on the right.

5. Discussion

Whereas the observed ~200 km scale height is met by all three modeled scenarios, only scenario number two, the oceanic water jet scenario, results in a narrow enough plume structure. Both scenarios number one and three are too broad to be in good agreement with the [2] observations. It thus seems that for the high radial scale height but the low latitudinal expansion a narrowing factor needs to be present, as for example a conduit-like geometry provides. The presence of a nozzle does not necessarily require that the liquid stems from the ocean, though. If a throat exists close to Europa's surface, it is also possible that a water inclusion close to the surface results in a jet-like geometry.

6. NIM Plume Observations

NIM is a highly sensitive neutral gas and ion mass spectrometer designed to measure the exospheres of the Europa, Ganymede, and Callisto. The detection limit is at 10-16 mbar for a 5 second integration time, which translates to a particle density of ~1 cm-3. NIM's mass resolution is M/ΔM > 1100 in the mass range 1-1000 amu. In addition to the modeled 3D plume density profiles, we will also present modeled mass spectra for the individual scenarios, and discuss their implications for positive plume identification possibilities.

7. Conclusion

The origin of the observed Europa water vapor plumes is of high scientific interest because the plume's chemical composition directly represents the reservoir's chemical composition. If the plume thus indeed originates in the ocean expected to lie underneath Europa's surface ice layer, analysis of its chemical omposition with a mass spectrometer would offer us direct information about the chemical composition of the water ocean itself. Such information would in turn teach us more about Europa's habitability, and about the possibility of Europa harboring life.

[1] Khurana, K. K., et al.: Induced magnetic fields as evidence for subsurface oceans in Europa and Callisto, Nature, Vol. 395, pp. 777-780, 1998.

[2] Roth, L., et al.: Transient water vapor at Europa's south pole, Science, Vol. 343, pp. 171-174, 2014.

[3] Wurz, P., and Lammer, H.: Monte-Carlo simulation of Mercury's exosphere, Icarus, Vol. 164, pp. 1-13, 2003.

How to cite: Vorburger, A. and Wurz, P.: Monte-Carlo Model of Europa's Water Vapor Plumes, Europlanet Science Congress 2020, online, 21 Sep–9 Oct 2020, EPSC2020-78, https://doi.org/10.5194/epsc2020-78, 2020.

Abstract

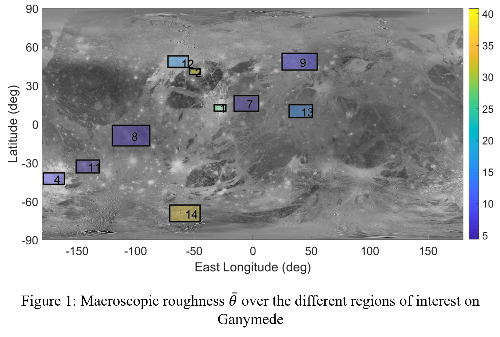

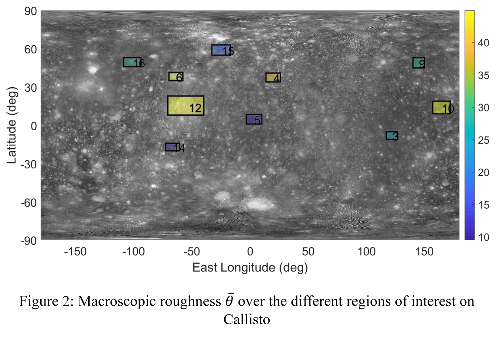

We carried out a regional study of Ganymede and Callisto’s photometry by estimating the parameters of the Hapke photometric models on a handful of regions of interest. We found that the photometry was diverse across the surface and highlighted areas with a distinct behavior that could indicate localized activity on Ganymede

Introduction

Jupiter’s icy moons are at the center of future space exploration missions such as ESA’s JUpiter ICy moons Explorer [1] and NASA’s Europa Clipper [2]. Ganymede, in particular, will be the primary target of the JUICE mission. Knowledge of the surface of Ganymede and Callisto is paramount to best plan the mission, help with navigation [3] and understand the its geology. In this study, we focus on the photometry of the surface and how we can describe it using the Hapke photometric model [4].

1. Dataset

We use images from the Voyager probes dataset taken with the Imaging Science System (ISS) [5] and from the New Horizons spacecraft taken with the LOng Range Reconnaissance Orbiter (LORRI) [6] with a ground resolution between 10 km and 30 km at the subspacecraft point. All Voyager images are limited to the clear filter.

2. Method

We need two elements to carry out this study: the reflectance and the geometry of observation. The first can be obtained after radiometric calibration of the images. The second necessitates accurate projections of each pixel.

2.1 Correction of metadata

We simulated images with SurRender [7] and compared those simulations to the real images to correct for spacecraft pointing and moon attitude. Additional distortion and distance corrections were needed and implemented on the Voyager images [8].

2.2 Model and Bayesian inversion

For this study we are considering the Hapke model detailed in Hapke, 1993 [4]. Six parameters are estimated: b, c, ω, θ, h and B0.

We have developed an inversion tool using a Bayesian approach based on previous work done on Mars [9, 10]. No a priori knowledge of the parameters were inferred except for their physical domain of variation. We also include in the model uncertainties on the absolute level reflectance (radiometric uncertainties) to correct for potential bias. This work is detailed in our previous study of Europa [11].

3. Results

3.1. Ganymede's regional photometry

We realized a regional photometric study of 15 areas of Ganymede with a very limited dataset of 16 images matching our criteria (see section 1) for which we corrected the metadata (spacecraft position and orientation) and radiometric calibration discrepancies.

We found that most of our areas are consistent with a global backscattering behavior of the surface with two notable exceptions - ROIs #2 and #4 (see fig. 1). They are situated in the polar latitudes, respectively in the north and in the south hemispheres. They are both very bright and rough and exhibit a strong and narrow forward scattering. This could be due to them being particularly favorable areas for ice redistribution at the poles or signs of possibly localized activity.

3.2. Callisto's regional photometry

We have estimated the photometric behavior of 16 regions of interest on Callisto's surface using 47 images per our selection criteria (see section 1).

Our phase coverage of Callisto is sparse, especially on the leading side, which makes it difficult to have reliable results. However, we have obtained fairly well constrained results for some areas. We have noted that θ - although in average higher than on Europa and Ganymede - shows some variation. ROI #2 is the palimpsest at the center of crater Valhalla. It is the brightest and roughest area that we sampled across Callisto's surface.

Although Callisto is the darkest of the three icy Galileans, we have identified a couple of bright and rough areas that show a strong and narrow forward scattering. We think they might be fields of knobs with frost on the crest as it is common to find frost deposits on topographical highs on Callisto [12].

Conclusion

The preliminary results of this study are very encouraging and show areas of particular interest that could be targeted by future missions. Overall, the general trends of our results are consistent with past integrated photometric studies [13, 14].

We plan on extending this work with more photometric models to find one that best describe the local photometry of both Ganymede and Callisto.

Acknowledgements

This work is supported by Airbus Defence & Space, Toulouse (France), the "IDI 2016" project funded by the IDEX Paris-Saclay, ANR-11-IDEX-0003-02 and the INSU, CNRS and CNES through the Programme National de Planétologie (PNP). Participation to EPSC 2020 is supported by ESAC.

References

[1] O. Grasset et al. An ESA mission to orbit Ganymede and to Characterize the Jupiter system, Planetary and Space Science, 2012

[2] Phillips and Pappalardo, Europa Clipper mission concept: Exploring Jupiter’s ocean moon, Eos, Transactions American Geophysical Union, 2014.

[3] G. Jonniaux et al. Autonomous vision-based navigation for JUICE. IAC, 2014

[4] B. Hapke, Theory of reflectance and emittance spectroscopy. Topics in Remote Sensing, Cambridge University Press, 1993

[5] A.Cheng , NEW HORIZONS Calibrated LORRI JUPITER ENCOUNTER V2.0, NH-J-LORRI-3-JUPITER-V2.0, NASA PDS, 2014.

[6] M. Showalter, VG1/VG2 JUPITER ISS PROCESSED IMAGES V1.0 VGISS_5101-5214, NASA PDS, 2013.

[7] R. Brochard et al. Scientific Image Rendering for Space Scenes with SurRender software, IAC, 2018.

[8] I. Belgacem et al. Image processing for precise geometry determination, under revision for Planetary and Space Science.

[9] J. Fernando, F. Schmidt, and S. Douté, Martian Surface Microtexture from Orbital CRISM Multi-Angular Observations: A New Perspective for the Characterization of the Geological Processes, Planetary and Space Science, 2016.

[10] F. Schmidt and S. Bourguignon, Efficiency of BRDF sampling and bias on the average photometric behavior Icarus, 2019.

[11] I. Belgacem et al. Regional study of Europa’s photometry, Icarus, 2019.

[12] J. M. Moore et al. Callisto in : Jupiter : The planet, Satellites and Magnetosphere, Cambridge University Press, 2004.

[13] B. J. Buratti, Photometry and Surface Structure of the Icy Galilean Satellites, Journal of Geophysical Research, 1995.

[14] D. L. Domingue and A. Verbiscer, Re-Analysis of the Solar Phase Curves of the Icy Galilean Satellites, Icarus, 1997.

How to cite: Belgacem, I., Schmidt, F., and Jonniaux, G.: Regional photometric study of Ganymede and Callisto, Europlanet Science Congress 2020, online, 21 Sep–9 Oct 2020, EPSC2020-83, https://doi.org/10.5194/epsc2020-83, 2020.

Abstract

The surface of Pluto is dominated by the Sputnik Planitia basin, possibly caused by an impact ~ 4 Gyr ago. To explain basin's unlikely position close to tidal axis with Charon, a reorientation driven by the post-impact uplift of the subsurface ocean was proposed recently. To maintain the reorientation until today, relaxation of the ice/ocean interface topography has to be sufficiently slow. Here we study the thermo-mechanical viscous relaxation of Pluto's ice shell of uneven thickness. We show that for a pure H2O ice shell the topography relaxes quickly (~ tens of Myr). On the other hand, if a layer of methane-clathrates is present at the base of the ice shell, the relaxation is much slower. With at least 5 km of clathrates, the ice/ocean interface topography can be maintained for 4 Gyr.

Introduction

Pluto, the largest dwarf planet in the Kuiper belt, is probably differentiated into a rocky core and a hydrosphere [9]. Its surface is dominated by the enigmatic Sputnik Planitia basin, which has likely been produced by a giant impact. The basin that covers about 7 % of Pluto's surface is located very close to the Charon tidal axis. To explain this unlikely position, [7] suggested that it may be the result of a whole body reorientation, which requires the crater to be a positive gravity anomaly. Isostatic uplift of the subsurface ocean was thus suggested to compensate the crater's negative gravity and an observed nitrogen layer [6] at the crater's surface to provide the positive signature necessary for the reorientation. However, it is not clear whether the ice/ocean interface topography is stable on long time scales. Here, we study the thermo-mechanical viscous relaxation of Pluto's ice shell of uneven thickness.

Numerical model

We solve thermal convection of ice in 2D cartesian geometry with time-evolving bottom boundary (interface with the ocean). The initial height of the ice/ocean interface is evaluated assuming Airy isostasy and a 6 km deep basin at surface. The governing equations are following:

Free surface is prescribed at the bottom boundary and free slip is prescribed elsewhere. Temperature is fixed at the top and bottom boundary (40 and 265 K) and the side boundaries are kept thermally insulating. The initial condition is steady-state conductive profile. In some simulations, a layer of methane-clathrate [4] of thickness hc is assumed. We use strongly nonlinear viscosity for ice dependent on temperature, grain size and stress using the composite law [2], and similarly for clathrates [1]. As a result, the viscosity of clathrate layer is at least one order of magnitude higher than the viscosity of ice immediately above. We prescribe temperature dependent thermal conductivity for ice [6] that gives values of 2.3 to 13 Wm-1K-1 at the ice/ocean interface and surface respectively. In the clathrate layer of thickness hc we prescribe constant thermal conductivity of 0.6 Wm-1K-1 [10]. We use the Arbitrary Lagrangian-Eulerian formulation to adress the moving boundary [8]. The problem is implemented in freely available Finite Element Method library FEniCS [5].

Results

We performed series of simulations with ice shell thickness h=150 km and clathrate layer thickness hc= 0, 5 and 10 km. The initial height of the ice/ocean interface topography is 87 km and grain size is d=1mm in all simulations.

Figure 1 shows the time evolution of temperature in the ice shell in case without clathrate hydrates layer (hc=0 km). We observe that the ice shell is relatively warm which results in low viscosities and thus relatively fast relaxation. In this setting, the ice/ocean interface topography disappears in about 5 Myr. Note that in this relatively warm, low-viscosity ice shell, thermal convection further increases the temperature (panels c and d).

Figure 2 shows the temperature (top) and viscosity (bottom) in the ice shell with hc=10 km after 100 Myr of relaxation. The insulating layer of clathrates at the ocean interface leads to significantly colder ice shell than in the case without clathrates. Therefore, the viscosity is also very high and no significant relaxation is observed.

Conclusions

We investigated the thermo-mechanical viscous relaxation of Pluto's ice shell using a numerical model with moving boundary. We showed that if Pluto's ice shell is made of pure H2O ice, the ice/ocean interface topography cannot be maintained for longer than a few tens of Myr. If an insulating layer of methane-clathrates is present at the ice shell/ocean interface, it may significantly delay the topography relaxation.

Future study will take into account a more realistic initial temperature condition resulting from the impact. In such case, one might expect that the effect of clathrates would be reduced and the relaxation would proceed faster. These results will be presented at the meeting.

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by the Czech Science Foundation through project No. 19-10809S. M.K. acknowledges the support from the Charles University projects SVV-2019-260447 and SVV-2020-260581. K.K. and O.S. were supported by the Charles University Research program No. UNCE/SCI/023.

References

[1] Durham et al. (2010). SSR. 153. 273-298.

[2] Goldsby Kohlstedt. (2001). JGR Solid Earth. 106. 11,017-11,030

[3] Hobbs (1974). Ice Physics. Clarendon Press, Oxford.

[4] Kamata et al. (2019). Nature Geoscience. 12. 407-410.

[5] Logg et al. (2012). The FEniCS Book, Springer-Verlag

[6] McKinnon et al. (2016), Nature, 534, 82-85.

[7] Nimmo et al. (2016). Nature. 540. 94-96.

[8] Scovazzi Hughes (2007), Sandia National Laboratories.

[9] Stern et al. (2015), Science, 350, 1815.

[10] Waite et al. (2006). GJI. 169. 767-774.

How to cite: Kihoulou, M., Kalousová, K., Souček, O., and Čadek, O.: Viscous relaxation of Pluto's ice shell below Sputnik Planitia, Europlanet Science Congress 2020, online, 21 Sep–9 Oct 2020, EPSC2020-91, https://doi.org/10.5194/epsc2020-91, 2020.

Abstract

We present preliminary results of a numerical study of tidally induced deformation of Enceladus’s ice shell containing fissures (Tiger Stripes) in the south polar region (SPR). It is a follow-up study of Souček et al. (2016), which brings in a more realistic description of the faults' behavior. In particular, the fault zone is described by a model of effectively visco-elasto-plastic material with yield stress depending on the stress state. Such a model mimics the Coulomb-type friction contact at idealized fault surfaces. We show the basic features of the model and discuss the importance of fault description on the predicted tidal deformation and stress field within Enceladus's ice shell.

Introduction

In Souček et al. (2016), we have numerically demonstrated a profound effect of faults (Tiger Stripes) on the tidally induced deformation and stress fields in the south polar region of Enceladus. In Běhounková et al. (2017), we showed how this effect can be further enhanced in a synergetic way, when combined with a realistic thinning of the ice shell in the SPR for a shell thickness model based on inversion of gravity and libration data (Čadek et al., 2016). In both these studies, the faults were modelled as zones with significantly reduced elastic moduli. Effectively, such description corresponds to faults being described as narrow slots partially filled with water (compensating the overburden pressure within the layer). Such description of the faults is oversimplified since it does not take into account any friction at the faults. We attempt to circumvent this deficiency in the new study.

Model

We solve equations of deformation of a 3D Maxwell visco-elastic planetary shell containing faults in the SPR. The shell's deformation is driven by the incremental tidal potential and at the fault, Coulomb, type response is considered. The Coulomb-type friction is mimicked by a continuum model of a fault zone of finite thickness with stress limiting viscosity. The stress limiter is given by the yield stress, composed of (hydro)static contribution due to overburden pressure and a dynamic contribution due to normal stress variations during the tidal period.

Results

We present preliminary results with one active fault in the SPR, corresponding to the Baghdad Sulcus. In Figure 1, we plot the displacement in SPR for four instants during the tidal period, colors indicate the amplitude of normal displacement, vectors show the horizontal displacement. Compared to the case with frictionless faults, the model with Coulomb-type friction exhibits asymmetry - the lateral motion is facilitated during the opening phase and suppressed during the closing (compressional) phase of the period.

Acknowledgements

The research leading to these results received funding from the Czech Science Foundation through project No. 19-10809S. The computations were carried out in IT4Innovations National Supercomputing Center (project no. LM2015070). The study was supported by the Charles University, project GA UK No. 304217, SVV-2019-260447 and SVV 115-09/260581 (K.S.), and by Charles University Research program No. UNCE/SCI/023 (O.S.).

References

Běhounková, M., Souček, O., Hron, J.and O. Čadek (2017), Plume activity and tidal deformation of Enceladus influenced by faults and variable ice shell thickness, Astrobiology, 17(9), 941-954, https://doi.org/10.1089/ast.2016.1629.

Čadek, O., Tobie, G., van Hoolst, T., Massé, M., Choblet, G., Lefèvre, A., Mitri, G., Baland, R.-M., Běhounková, M., Bourgeois, O., and Trinh, A. (2016) Enceladus’s internal ocean and ice shell constrained from Cassini gravity, shape, and libration data. Geophys Res Lett 43:5653–5660.

Souček, O., Hron, J., Běhounková, M., and O. Čadek (2016), Effect of the tiger stripes on the deformation of Saturn's moon Enceladus, Geophysical Research Letters, 43(14), 7417–7423, https://doi.org/10.1002/2016GL069415.

How to cite: Souček, O., Sládková, K., Běhounková, M., and Čadek, O.: Tiger stripes revisited - effect of fault zone rheology, Europlanet Science Congress 2020, online, 21 Sep–9 Oct 2020, EPSC2020-95, https://doi.org/10.5194/epsc2020-95, 2020.

Introduction

The presence of an internal ocean in direct contact with silicates and possible seafloor magmatic activity drew attention to the potential habitability of Jupiter's moon, Europa. Here, we address the conditions for melt production in its silicate mantle until the present day, an essential ingredient for assessing the habitability potential of Europa.

Method

To reach our goal we employ Oedipus/Antigone (Choblet et al., 2007; Běhounková et al., 2010) – a numerical tool solving consistently thermal convection and tidal dissipation in 3d planetary shells. For the thermal convection part, the mass, momentum and energy conservation equations for viscous material are solved in the extended Boussinesq approximation. The solved equations are supplemented by an instantaneous melt extraction model once the solidus temperature is reached. The efficiency of heat transfer is mainly determined by viscosity, characterized by viscosity at the melting point 𝜂melt and strong temperature dependency. We consider both radiogenic and tidal heating as energy sources. The former is computed from long-lived radioisotope abundances assuming concentrations based on LL (upper limit) and CM (lower limit) chondrites. Two families of models are tested: homogeneous distribution and a model with a simple 50:50 partitioning of radioactive elements between the crust and the mantle. The time-evolution follows the decay law and is progressively diminishing with time. The latter is controlled by internal structure and Europa’s orbital eccentricity. For the tidal dissipation part, the mass and momentum conservation of tidal deformations are solved over the tidal time scale assuming a Maxwell viscoelastic rheology with a temperature-dependent effective viscosity capturing an Andrade-like behaviour. The orbital eccentricity and the eccentricity evolution are parameterized. Two families of eccentricity models are taken into account assuming either constant or periodically varying eccentricity (cf. Hussmann and Spohn, 2004).

Results

Our simulations show that the evolution of Europa's silicate mantle and associated melt production are controlled by three primary parameters: i) the viscosity at the melting temperature 𝜂melt, ii) the amount of radiogenic heating and its partitioning, and iii) Europa’s orbital eccentricity.

For viscosity equal or larger than 1020Pa.s, no onset of convection is observed, the melt production is concentrated into the layer above the core-mantle boundary, and melt production can be sustained until the present day.

For lower viscosity (𝜂melt=1018 or 1019 Pa.s), more effective heat transfer is obtained. All the performed simulations follow a similar pattern. The onset of convection is observed within 1 Gyr and 100 Myr for 1019 Pa.s and 1018 Pa.s, respectively. Due to the large volumetric heating, the mantle temperature is close to the dry silicate solidus except in the cold lid and the temperature differences are relatively small below the lid. The onset of convection can, therefore, occur after a relatively long time, especially for 𝜂melt=1019 Pa.s, and the exact timing is sensitive to the radiogenic heating model. The onset of convection is characterized by abrupt changes in melt production and in temperature, and by increased flux from the core. The temperature during the onset is represented by long-wavelength features following the pattern of heterogeneous tidal dissipation. After the onset of convection, the melting production concentrates into the layer just under the stagnant lid, the thickness of this layer depends on the viscosity.

For models with constant eccentricity equal to the present-day value, no melt production is expected at present (except for non-convective models with high reference viscosity). Only simulations with enhanced eccentricity can lead to melt production during the last billion years. Increased tidal dissipation during periods of enhanced eccentricity leads to prolonged melt production at high latitudes, even at present.

We predict that melt can be currently produced in the polar regions if Europa experienced a recent period of enhanced eccentricity. This would also imply the eccentricity is presently decreasing. The volume of melt that is produced during such a magmatic pulse and the associated volatile release depends on the assumed initial rock composition, which determines the abundance in radioactive elements and volatile species.

Conclusions

We have investigated the thermal evolution of Europa's mantle and conditions for sustaining melt production until the present. Present-day seafloor magmatism might be possible if Europa experienced a period of increased eccentricity in the recent past. Such recent magmatism should influence the topography of the seafloor and composition of the ocean (Zolotov and Kargel, 2009; Dombard and Sessa 2019). Characterization of the ocean composition, and possible detection of gravity anomalies, hydrothermally derived volatile species at high latitude, and changes in Europa’s orbital motion by Europa Clipper and JUICE may confirm possible ongoing large-scale seafloor activity.

Acknowledgements

The research leading to these results received funding from the Czech Science Foundation through project No. 19-10809S, from the French ”Agence Nationale de Recherche” ANR (OASIS project, ANR-16-CE31-0023-01), from CNES (JUICE and Europa Clipper missions), from the Région Pays de la Loire - GeoPlanet consortium project (No. 2016-10982). The computations were carried out in IT4Innovations National Supercomputing Center (project no. LM2015070).

References

Behounkova, M., Tobie, G., Choblet, G., and Cadek, O.: Coupling mantle convection and tidal dissipation: Applications to Enceladus and Earth-like planets. Journal of Geophysical Research Planets, 115, E09011, (2010).

Choblet, G., Cadek, O., Couturier, F. and Dumoulin, C. OEDIPUS: A new tool to study the dynamics of planetary interiors. Geophysical Journal International 170, 9–30 (2007).

Dombard, A.J., and Sessa, A.M. Gravity measurements are key in addressing the habitability of a subsurface ocean in Jupiter's Moon Europa, Icarus 325, 31–38 (2019).

Hussmann, H. and Spohn, T.: Thermal-orbital evolution of Io and Europa. Icarus, 171, 391–410, (2004).

Zolotov, M. Y. and Kargel, J.: On the chemical composition of Europa’s icy shell, ocean, and underlying rocks. Europa, edited by R.T. Pappalardo, W.B. McKinnon, and K. Khurana, University of Arizona Press, Tucson, AZ, pp. 431–458 (2009).

How to cite: Behounkova, M., Tobie, G., Choblet, G., Kervazo, M., Melwani Daswani, M., Dumoulin, C., and Vance, S.: Conditions for present-day magmatism in Europa's mantle, Europlanet Science Congress 2020, online, 21 Sep–9 Oct 2020, EPSC2020-98, https://doi.org/10.5194/epsc2020-98, 2020.

Triton: Scientific Motivation

Neptune’s moon Triton is one of the most interesting and surprising targets observed by Voyager. During its distant flyby in 1989, Voyager 2 captured a series of images, mostly of the southern, sub-Neptune hemisphere, establishing Triton as one of a rare class of solar system bodies with a substantial atmosphere and active geology. It is believed that Triton began as of a Dwarf Planet originating in the KBO, and subsequently captured by Neptune. It nor exists as Neptune’s icy satellite, and is subject to a tidal, radiolytic, and collisional environment. It is this duality as both captured dwarf planet and large icy satellite that has undergone extreme collisional and tidal processing that gives us a unique target for understanding two of the Solar System's principal constituencies and the fundamental processes that govern their evolution. Thus, comparisons between Triton and other icy objects will facilitate re-interpretation of existing data and maximize the return from prior NASA missions, including New Horizons, Galileo, Cassini and Dawn.

Triton’s surface and atmosphere are remarkable, but poorly understood. They hint at on-going geological activity, suggesting an active interior and a possible subsurface ocean. Crater counts suggest a typical surface age of <10 Ma (Schenk and Zahnle, 2007), with more conservative upper estimates of ∼50 Ma on more heavily cratered terrains, and ∼6 Ma for the Neptune-facing cantaloupe terrain. This implies Triton’s surface is young, almost certainly the youngest of any planetary body in the solar system (except Io). The lack of compositional constraints obtained during Voyager, largely due to the lack of an infrared spectrometer, means that many of Triton’s surface features have been interpreted as possibly endogenic based on comparative photogeology alone. Candidate endogenic features include: a network of tectonic structures, including most notably long linear features which appear to be similar to Europa’s double ridges (Prockter et al., 2006); several candidate cryovolcanic landforms (Croft et al., 1995), best explained by the same complex interaction among tidal dissipation, heat transfer, and tectonics that drives resurfacing on Europa, Ganymede, and Enceladus; widespread cantaloupe terrain, unique to Triton, is also suggested non-uniquely to be the result of vertical (diapiric) overturn of crustal materials (Schenk and Jackson, 1993); and several particulate plumes and associated deposits. Despite an exogenic solar-driven solid-state greenhouse effect within nitrogen ices being preferred initially (Kirk et al., 1990), some are starting to question this paradigm (Hansen and Kirk, 2015) in the context of observations of regionally-confined eruptive on the much smaller Enceladus.

Endogenic heating is likely, with radiogenic heating alone possibly providing sufficient heat to sustain an ocean over ~4.5 Ga (Gaeman et al., 2012). Orbit capture (e.g. McKinnon, 1984; Agnor and Hamilton, 200)) would have almost certainly resulted in substantial heating (McKinnon et al., 1995). The time of capture is not constrained, but if sufficiently recent some of that heat may be preserved. Triton’s orbit is highly circular but with a high inclination that results in significant obliquity, which should be sufficient to maintain an internal ocean if sufficient “antifreeze” such as NH3 is present (Nimmo and Spencer, 2015). Confirmation of the presence of an ocean would establish Triton as arguably the most exotic and probably the most distant ocean world in the solar system, potentially expanding the habitable zone.

Even if activity or an ocean is not present, Triton remains a compelling target. Its atmosphere is thin, ~1 Pa, 10-5 bar, but sufficient to be a major sink for volatiles, and sufficiently dynamic to play a role in movement of surface materials. Its youthful age implies a highly dynamic environment, with surface atmosphere volatile interchange, and potentially dramatic climate change happening over obliquity and/or season timescales. An extensive south polar cap, probably mostly consisting of nitrogen which can exchange with the atmosphere, was observed.

A north polar cap on Triton was not detected (in part due to a lack of high northern latitude coverage). However, not even the outer limits of such a structure were detected, implying a north/south dichotomy. Methane in Triton’s atmosphere and on its surface makes possible a wide range of “hot atom” chemistry allowing higher order organic materials to be produced in a similar albeit slower manner to Titan. The presence of such materials is of potential importance to habitability, especially if conditions exist where they come into contact with liquid water.

Trident Mission Concept

We were selected by NASA for Phase A study in February 2020, baselining a New Horizons-like fast flyby of Triton in 2038. The mission concept uses high heritage components and builds on the New Horizons concepts of operation. Our overarching science goals are to determine: (1) Determine if Triton has a subsurface ocean or had one in recent history; (2) Understand the mechanisms by which Triton is resurfaced and what energy sources and sinks are involved; and (3) Investigate the diversity, production, and distribution of organic constituents on Triton’s surface. If an ocean is present, we seek to determine its properties and whether the ocean interacts with the surface environment. To address these questions, we propose a focused instrument suite consisting of:

(1) a magnetometer, primarily for detection of the presence of an induced magnetic field which would indicate compellingly the presence of an ocean;

(2) a camera, for imaging of the mostly unseen anti-Neptune hemisphere, and repeat imaging of the sub-Neptune hemisphere to look primarily for signs of change;

(3) an infrared imaging spectrometer with spectral range up to 5 um, suitable for detection and characterization of surface materials at the scales of Triton’s features.

References

Agnor and Hamilton, Nature 441, 192–194, 2006.

Croft et al., Neptune and Triton. Univ. Arizona Press, pp. 879–947, 1995.

Gaeman et al., Icarus 220, 339–347, 2012.

Hansen and Kirk, In Lunar Planet. Sci. XLVI, Abstract #2423, 2015.

Kirk et al., Science 250, 424–429, 1990.

McKinnon and Leith, Icarus 118, 392-413, 1995.

McKinnon, Nature 311, 355-358, 1984.

Nimmo and Spencer, Icarus 246, 2-10, 2015.

Prockter et al., Geophys. Res. Lett. 32, L14202, 2005.

Schenk and Zahnle, Icarus 192, 135–1492007.

Schenk and Jackson, Geology 21, 299–302, 1993.

How to cite: Howett, C., Procktor, L., Mitchell, K., Bearden, D., and Smythe, W.: Trident: A Mission to Explore Triton, a Candidate Ocean World, Europlanet Science Congress 2020, online, 21 Sep–9 Oct 2020, EPSC2020-138, https://doi.org/10.5194/epsc2020-138, 2020.

Introduction: The potential habitability of the icy moons of Jupiter and Saturn, in particular Europa and Enceladus, has been hotly debated in recent years. There is evidence of subsurface liquid water oceans [1], and complex organic molecules (>200 amu) have been detected in the plumes from Enceladus [2]. Plumes are also thought to arise from the surface of Europa [3], which will be the target of the Europa Clipper spacecraft, due to be launched in a few years. In a similar manner to the Ion and Neutral Mass Spectrometer (INMS) on Cassini [4], the Europa Clipper will also carry a mass spectrometer, MASPEX [5], enabling molecular detection of material in the plumes.

Extremophile Archaea and Bacteria, besides being some of the simplest known forms of life, can withstand extreme conditions of temperature, salinity and acidity, and have been observed in hydrothermal vents on Earth. Similar organisms are the most likely candidates for life on icy moons.

The purpose of our current work is to study the mass spectral fingerprint of earthly simple Archaea and Bacteria to understand the spectra that would arise from similar organisms in the vicinity of icy moons and distinguish them from abiotic compounds. Nonbiological organic materials generally have complete structural diversity and are characterized by the presence of racemic mixtures and polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs). These are absent in biological materials which tend to have specific structures and show chiral preference.

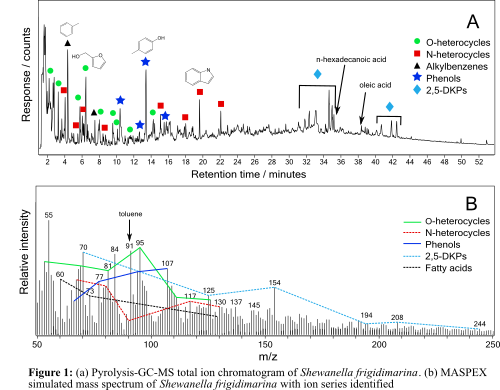

Methods: Different strains of Archaea and Bacteria, including cyanobacteria, were obtained in freeze-dried form (DSMZ GmbH). These include extremophiles isolated from sea ice (Shewanella frigidimarina) and hot springs (Metallosphaera hakonensis). They were analyzed in pure form with flash pyrolysis-GC-MS. This enabled identification of the decomposition fragments that are representative of the different components of bacteria.

Flash pyrolysis offers a good analogue of the impact fragmentation that occurs as the spacecraft flies through a plume. In our experiments pyrolysis is coupled with gas chromatography-mass spectrometry (GC-MS). This separates the pyrolysis products, enabling identification of individual molecules. This GC stage is missing on the spacecraft instruments but simulated INMS or MASPEX spectra can be reconstructed from the chromatograms.

Additional experiments were carried out to understand the degradation of bacterial signals under conditions relevant to icy moons. Hydrous pyrolysis was used to simulate hydrothermal degradation, where bacteria are subjected to increased pressures and temperatures, in the presence of water [6].

Results: Our results show that pyrolysis-GC-MS analysis of intact archaea and bacteria produces distinctive fingerprints of biotic substances, shown in Figure 1. Decomposition products from protein, amino acid, carbohydrate and lipid species were detected from all the strains analyzed. The compound types detected are detailed in Table 1.

| Compound type | Possible origin |

| Alkylbenzenes, e.g. toluene, styrene, ethylbenzene | Protein |

| Nitrogen containing heterocycles, e.g. indole, benzyl nitrile, pyrrole | Proteins, amino acids |

| 2,5-Diketopiperazines | Peptides, proteins |

| Oxygen containing heterocycles (furans), e.g. methyl-furan, dimethyl-furan, furfural, maltol | Carbohydrates |

| Phenols, e.g. phenol, cresol | Protein, carbohydrates |

| Alkanes | Lipids |

| Fatty acid, e.g. hexadecenoic acid | Lipids |

Table 1: Possible origin of compound types detected from bacteria and archaea analyzed with pyrolysis-GC-MS.

Using GC-MS, we have been able to identify the molecules detected, shown in Figure 1A, and hence identify the ion series that represent specific compound types which are related to different components of the organisms. These ion series greatly help with the interpretation of complex mass spectra when no separation technique is present, i.e. in INMS and MASPEX. The chromatogram can be converted into a mass spectrum, Figure 1B, with lines joining the peaks in a specific series. This mass spectrum is more representative of the data acquired in space missions.

Although only a relatively small number of strains have been analyzed in this study, there is diversity among the results obtained with differing ratios of carbohydrate and protein products detected. However, all the strains also share common features, such as the presence of indole and phenols.

The mass spectra obtained from Archaea and Bacteria are clearly different from those of abiotic materials such as meteorites [7], which show features as discussed in the Introduction. This shows that mass spectrometry is a powerful technique for distinguishing between non-biological and biological materials.

As well as understanding the mass spectra of intact bacteria, it is important to understand how these spectra will change under different sample processing methods. Thermal processing is likely to be present on icy moons, both on and under the icy crust and as material is ejected into space. Hydrous pyrolysis can also simulate conditions near hydrothermal vents. Increased amounts of sample processing degrade the biotic fingerprint of the bacteria. Understanding the degradation pattern and being able to recognize where the spectral features originate from may play an important role in future spectral interpretation. It will also be important to note at what point the compounds detected become indistinguishable from abiotic materials.

Acknowledgments: We thank the MASPEX team for useful discussions.

References: [1] Pappalardo R. T. et al. (1999) J. Geophys. Res., 104 (E10), 24015-24055. [2] Postberg F. et al. (2018) Nature, 558, 564-568. [3] Paganini L. et al. (2019) Nat. Astron., doi:10.1038/s41550-019-0933-6. [4] Waite J. H. et al. (2004) Space Sci. Rev., 114, 113–231. [5] Brockwell T. G. et al. (2016) IEEE Aerospace Conference 2016. [6] Sephton M. A. et al. (1999) Planet. Space Sci., 47, 181-187. [7] Sephton M. A. et al. (2018) Astrobiology, 18, 7, 843-855.

How to cite: Salter, T., Waite, H., and Sephton, M.: Mass spectrometric fingerprints of Archaea and Bacteria for life detection on icy moons, Europlanet Science Congress 2020, online, 21 Sep–9 Oct 2020, EPSC2020-143, https://doi.org/10.5194/epsc2020-143, 2020.

The research project: "Ganimede from 2D to 3D: A multidisciplinary approach in preparation for JUICE", was selected in 2019 in the framework of an "INAF Mainstream" call. This work aims to show the potential of a multidisciplinary data analysis approach in anticipation of the JUICE mission.

We focus on three instruments carried onboard the ESA JUICE mission, where Italy's National Institute for Astrophysics (INAF) is involved: the optical camera (JANUS), sensitive to the 0.4-1.0 µm spectral region [1], the VIS-NIR imaging spectrometer (MAJIS), operating in the overall 0.5-5.54 µm spectral domain [2], and the radar sounder (RIME), operating at 9 MHz (33.3 m) [3]. This project is important to prepare combined analysis techniques and models that could be applied to a larger number of regions of interest that will be observed by JUICE in the 2030s, when data of the icy Galilean moons will be finally acquired. Here we show regions of interest on Ganymede that are most promising for a multi-sensor data analysis, first of all by combining optical images acquired by the Galileo/SSI framing camera and by the Galileo/NIMS imaging spectrometer with good spatial resolution. Unfortunately, topographic information is currently not available for most of the Ganymede's surface. However, we built a synthetic topographic dataset for the Nippur Sulcus region based on the existing high-resolution optical images, which could be representative of topographic models that will be obtained in the future by means of JUICE data. We process such a synthetic topographic dataset with a self-similar clustering method [e.g., 4] able to model how the fractures are distributed not only on the surface, but also inside the icy crust.

In the near future, this synthetic topographic dataset will also be used to apply a code able to simulate radar echoes coming from the radio waves investigation of Ganymede's subsurface, which was successfully tested on Mars by means of the MARSIS radar data [5].

Among other things, the study of specific regions of interest on Ganymede is key to drive the planning and prioritization of the observations to be carried out by multiple JUICE instruments, especially during the dedicated Ganymede orbit phase, which will be the final and salient phase of the entire mission.

References

[1] Della Corte, V., Noci, G., Turella, A., Paolinetti R., et al. (2019). Scientific objectives of JANUS Instrument onboard JUICE mission and key technical solutions for its Optical Head. Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE 5th International Workshop on Metrology for AeroSpace, Turin (Italy), 19-21 June 2019. Doi: 10.1109/MetroAeroSpace.2019.8869584.

[2] Piccioni, G., Tommasi, L., Langevin, Y., Filacchione, G., et al. (2019). Scientific goals and technical challenges of the MAJIS imaging spectrometer for the JUICE mission. Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE 5th International Workshop on Metrology for AeroSpace, Turin (Italy), 19-21 June 2019. Doi: 10.1109/MetroAeroSpace.2019.8869566.

[3] Bruzzone, L., Croci, R. (2019). Radar for Icy Moon Exploration (RIME). Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE 5th International Workshop on Metrology for AeroSpace, Turin (Italy), 19-21 June 2019. Doi: 10.1109/MetroAeroSpace.2019.8869624.

[4] Lucchetti, A., Pozzobon, R., Mazzarini, F., Cremonese, G., Massironi, M. (2017). Brittle ice shell thickness of Enceladus from fracture distribution analysis. Icarus 297, 252-264. Doi: 10.1016/j.icarus.2017.07.009.

[5] Orosei, R., Rossi, A. P., Cantini, F., Caprarelli, et al. (2017). Radar sounding of Lucus Planum, Mars, by MARSIS. Journal of Geophysical Research (Planets) 122 (7), 1405-1418. Doi: 10.1002/2016JE005232.

How to cite: Tosi, F., Lucchetti, A., Zambon, F., Galluzzi, V., Orosei, R., Cremonese, G., Filacchione, G., Palumbo, P., and Piccioni, G.: Ganymede from 2D to 3D: A multidisciplinary approach in preparation for JUICE. Preliminary results., Europlanet Science Congress 2020, online, 21 Sep–9 Oct 2020, EPSC2020-197, https://doi.org/10.5194/epsc2020-197, 2020.

1. Introduction

The Saturnian moon Enceladus exhibits large cryovolcanic plumes sourced from a subsurface ocean which contain evidence of endogenic organic chemistry and ongoing hydrothermal activity [2-4]. Salt-rich ice particles observed in the plumes by the Cassini spacecraft are interpreted as rapidly frozen ocean spray [5] thus studying them provides a means of probing the chemistry, habitability and potential biology of an extraterrestrial ocean. A crucial step in understanding these particles is to determine the composition and sequence of solid phases that form upon freezing of Enceladus ocean fluids. We investigated the partitioning of ice and non-ice materials and the pH-dependence of cryogenic mineral formation using simulated Enceladus ocean fluids at contrasting cooling regimes: (i) flash freezing of ~4 µl droplets into liquid nitrogen (>10 K s-1), and (ii) slow freezing near equilibrium (~0.01 K s-1). Fluids were designed based on up-to-date constraints provided by Cassini data and modelling efforts [1,2,4,6]. Our findings provide new endmember constraints on the range of products produced by Enceladan cryovolcanism.

2. Results & Discussion

2.1. Kinetic inhibition of crystallisation during flash freezing

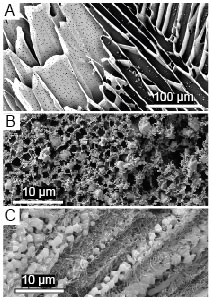

Imaging via cryo-scanning electron microscopy shows that flash-freezing produces a glass-like non-crystalline phase accumulated at ice grain boundaries (Fig. 1A). The formation of this ‘brine vein’ network demonstrates that ice had formed and solutes were excluded. Glasses represent a homogenous, unfractionated snapshot of fluid composition and would provide an ideal mechanism for preserving organics or microorganisms in their native state.

Fig. 1. A. Interior of flash-frozen droplet, showing ice (dark regions) and glass-like phase (lighter material). Imaged at 123 K, partially sublimated. B. Crystals formed through re-warming flash-frozen fluids. C. Crystals formed through slow freezing.

2.2. Production of crystalline materials within brine veins

We found that salt minerals can form within the confines of brine veins through two contrasting routes: direct crystallisation during cooling (during gradual freezing), or ‘cold crystallisation’ upon warming of flash-frozen samples. These contrasting mechanisms were reflected in the distribution of salt crystals; flash-frozen samples exhibited random crystal distributions, homogenous at the 10 µm scale, whereas crystals produced by slow freezing were arranged in clusters of locally distinct crystal types and highly heterogenous at the 10 µm scale (Fig. 1B,C). These crystallisation textures record the rapidity at which the system solidified, with crystal growth of different phases occurring either simultaneously (in flash-frozen samples) or in a thermodynamically defined sequence (in gradually-frozen samples).

2.3. Mineralogy of cryogenic salts

Measurements of bulk mineralogy using X-ray diffraction showed that at pH 11, carbonate assemblages were dominated by thermonatrite (Na2CO3.H2O), whereas at pH 9 trona (Na3H(CO3)2.2H2O) and nahcolite (NaHCO3) were the major phases (Fig. 2). This demonstrates that carbonate mineral assemblages can function as an independent pH probe for Enceladus’s ocean. Furthermore, at pH 9, nahcolite was kinetically inhibited by flash-freezing. Hence for lower pH fluids, the presence of nahcolite is an indicator of more gradual freezing whereas its absence may indicate kinetically-limited freezing.

Fig. 2. X-ray diffraction patterns collected from crystalline cryogenic salts. Identified peaks are: H, Halite (NaCl); S, Sylvite (KCl); Tr, Trona (NaH3(CO3)2.2H2O); Th, Thermonatrite (Na2CO3.H2O); N, Nahcolite (NaHCO3). Note largest halite peaks at 37.0 and 53.5° (2θ) are truncated for clarity.

3. Conclusions

Our experiments describe contrasting scenarios for solid phase production upon cooling of fluids with an Enceladus ocean composition, each of which leaves a compositional and textural signature of its formation route. Whether glass forms at Enceladus depends on the thermal history of ocean aerosols as they travel upwards from the liquid/vapour interface to space. Particles encountered by Cassini that consist of pure water ice or ice and organics imply that condensation must occur throughout some portion of the Enceladus crack depth and thus that re-warming is likely [1,3]. Due to the self-limiting nature of evaporative cooling and the likelihood of re-warming a conservative assumption is that crystalline salts are more likely than glass in the Enceladus plumes. If crystalline material exists, its mineralogical composition and micron-scale partitioning can record fluid pH and delineate between thermodynamically defined crystallization in sequence, and kinetically limited simultaneous crystallisation. Based on these findings, non-destructive measurements of plume particles could open powerful new avenues of investigation at Enceladus and other bodies that display evidence for cryovolcanic processes, such as Ceres or Jupiter’s moon Europa.

References:

[1] Postberg et al. Nature 459, 1098-1101 (2009)

[2] Waite, J. H. et al. Science 356, 155–159 (2017)

[3] Postberg, F. et al. Nature 558, 564–568 (2018)

[4] Hsu, H.-W. et al Nature 558, 564–568 (2018)

[5] Porco, C. C. et al. Science 311, 1393–401 (2006)

[6] Glein et al. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 162, 202–219 (2015)

How to cite: Fox-Powell, M. and Cousins, C.: Production of crystalline and amorphous phases during freezing of simulated Enceladus ocean fluids, Europlanet Science Congress 2020, online, 21 Sep–9 Oct 2020, EPSC2020-199, https://doi.org/10.5194/epsc2020-199, 2020.

In the coming years The JUpiter ICy moons Explorer (JUICE) (ESA) and Europa Clipper (NASA) missions will study the icy crusts of the main Galilean moons of Jupiter. They will use the penetrating radars RIME and REASON, which will work at wave frequency ranges able to penetrate up to 9 and 30 Km depth respectively, in combination with other instruments [Bruzzone et al. 2013, Aglyamov et al. 2017].

In this regard, we have started a set of experiments to study the electrical properties of materials at low temperatures with the aim to help with the interpretation obtained from the level of attenuation of the radar waves. Ultimately, they will be useful to constrain the chemical composition, physical state and temperature of the upper layers of the icy crusts of Ganymede, Callisto and Europa (please see abstracts EPSC González Díaz et al. 2020 and EPSC Solomonidou et al. 2020).

The first set of experiments have been done in a high-pressure chamber equipped with pressure and temperature sensors in direct contact with the sample and a large sapphire window which allows textural and spectroscopic analyses. We have characterized aqueous solutions with salts (MgSO4, NaCl, MgCl2, Mg(ClO4)2, Na2CO3), volatiles (CO2) and clays (nontronite, montmorillonite) at temperatures down to 223 K and pressures up to 60 MPa. Samples were studied by pressure-temperature (P-T) cycles in two ways: (a) first freezing the solution and pressurizing it (TPPT method) and (b) first pressurizing the solution and then freezing it (PTTP method), in order to examine textural and grain size heterogeneities and fracture formation depending on the method of formation. The cooling of the samples led to the final formation of water ice, hydrated salts and clathrate hydrates. Raman spectroscopy was used to control the mineral assemblages and understand better the crust environments and processes that can explain the resulting values, like the appearance of supercooled brines, amorphous phases and recrystallizations during the P-T cycles.

We measured the dielectric properties of these samples with a BDS80 Broadband Dielectric Spectroscopy system (Novocontrol) which allows to work in a frequency range from 1 Hz to 10 MHz and temperatures from 143 to 323 K. Both permittivity and electric conductivity were measured at 0.1 MPa while cooling the samples in temperature steps of 10 K. From these data we estimated, on the one hand, the activation energy for motion of the electric charges of each solution, and on the other hand, the attenuation of the radar wave depending on the chemical composition and the temperature of the sample, and the frequency of the electric field applied [Pettinelli et al. 2015].

The already obtained novel data will be used as reference for a second set of experiments, consisting on the same dielectric properties’ characterization but, in this set, samples will be also subjected to high pressure conditions.

References

Aglyamov et al. (2017) Bright prospects for radar detection of Europa’s ocean, Icarus, 281, 334-337.

Bruzzone et al. (2013) RIME: Radar for Icy moon Exploration, IEEE International Geoscience and Remote Sensing Symposium - IGARSS, Melbourne, 3907-3910.

Pettinelli et al. (2015) Dielectric properties of Jovian satellite ice analogs for subsurface radar exploration: A review, Reviews of Geophysics, 53, 593-641.

How to cite: Muñoz-Iglesias, V., Prieto-Ballesteros, O., Ercilla Herrero, O., Sánchez-Benítez, J., Rivera-Calzada, A., Muñoz Caro, G. M., González Díaz, C., Carrascosa de Lucas, H., Aparicio Secanellas, S., González Hernández, M., Anaya Velayos, J. J., Anaya Catalán, G., Lorente, R., Altobelli, N., Solomonidou, A., Vallat, C., and Witasse, O.: Dielectric properties of aqueous solutions, amorphous phases and hydrated minerals in support for future radar measurements of Jovian icy moons, Europlanet Science Congress 2020, online, 21 Sep–9 Oct 2020, EPSC2020-205, https://doi.org/10.5194/epsc2020-205, 2020.

Introduction

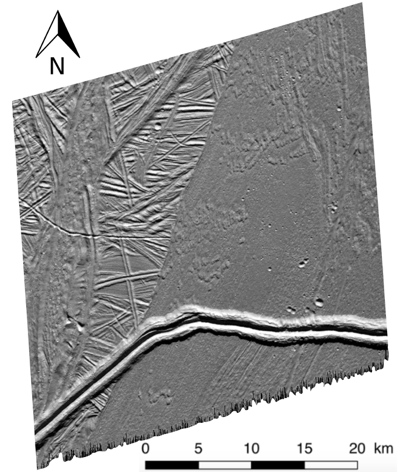

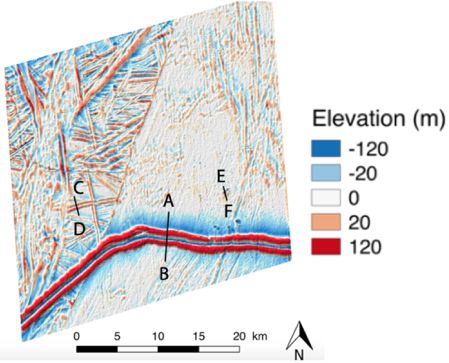

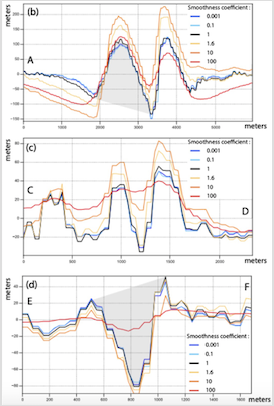

Smooth bright terrains represent the stratigraphically youngest geological units on Ganymede. One plausible theory explaining their unusual smoothness is based on cryo-volcanic eruptions of low-viscosity water-ice lava, flooding the pre-existing rough terrain to an equipotential flat surface [1]. The cryo-volcanic resurfacing hypothesis is interesting since it implies the presence of local melting or liquid water in the shallow crust of Ganymede. However, due to lack of concrete evidence of source vents of cryo-magma, the theories of cryovolcanic origins of the bright terrain are debatable.

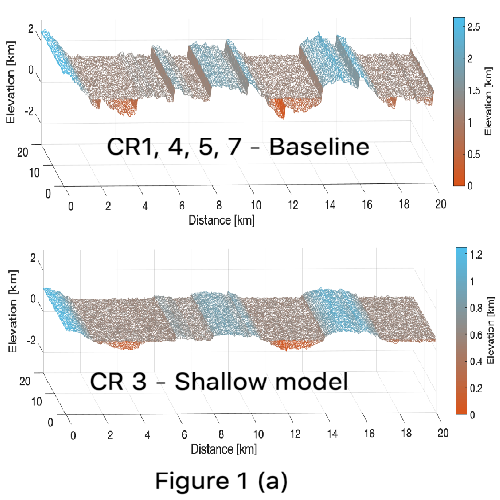

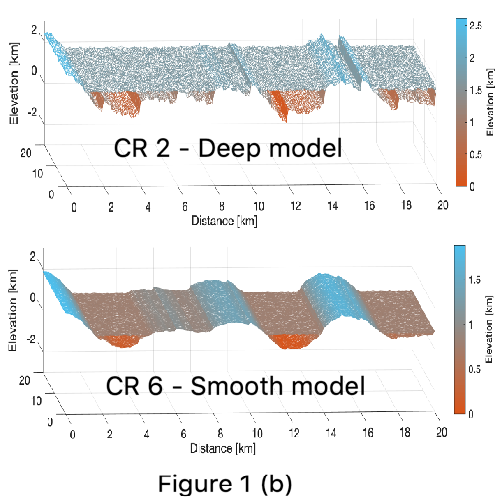

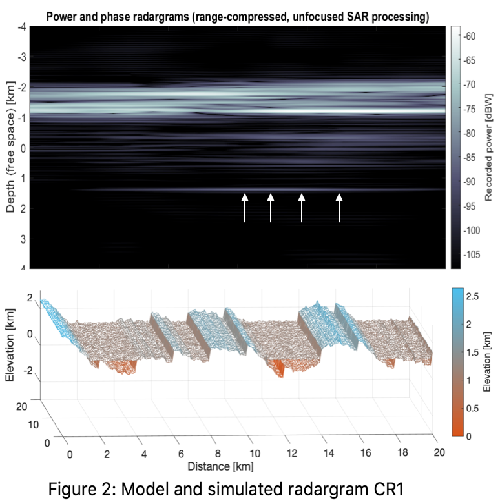

These ambiguities can be resolved by directly imaging the subsurface using low-frequency ice-penetrating radar sounders. This is the case of the Radar for Icy Moon Exploration (RIME) [2] on board the ESA’s Jupiter Icy Moons Explorer (JUICE). RIME is designed to achieve a penetration up to 9 km through the ice crust, by operating at a central frequency of 9 MHz with a programmable bandwidth (high-resolution 2.8 MHz, low-resolution 1 MHz). In order to understand the RIME capability in resolving the possible evidence of cryovolcanic resurfacing, it is necessary to model the radar response using radar sounder simulations.