Multiple terms: term1 term2

red apples

returns results with all terms like:

Fructose levels in red and green apples

Precise match in quotes: "term1 term2"

"red apples"

returns results matching exactly like:

Anthocyanin biosynthesis in red apples

Exclude a term with -: term1 -term2

apples -red

returns results containing apples but not red:

Malic acid in green apples

hits for "" in

Network problems

Server timeout

Invalid search term

Too many requests

Empty search term

SB12

We particularly encourage presentations on scientific results using data from past and present missions as well as abstract addressing the future exploration of Phobos and Deimos, including mission and instrument concepts and developments, and preparation studies for the upcoming JAXA’s Martian Moon eXploration (MMX) mission.

Session assets

The goal of the MMX mission is to determine the origin and the formation process of the two Martian moons (Kuramoto et al. 2022). Three years remote sensing observation of Phobos and Deimos (Nakamura et al .2021) will provide us mineralogical and compositional signatures of whole sphere of the moons and thus we will obtain strong constraints on the origin. Subsequent laboratory analysis of the returned samples from Phobos will terminate the long-standing problem of the origin of Martian moons.

In some cases, we can determine the origin based on only remote sensing observation. If Phobos has a high abundance of hydrous minerals, a high hydrogen concentration, a chondritic global chemical composition, and a reflectance spectrum similar to hydrous carbonaceous meteorites, then Phobos is made of primitive C or D-type asteroidal material. In this case, Phobos could be a captured asteroid coming from beyond Mars, or if it was formed by an asteroid impacting Mars, the impact would have been weak to maintain chondiritic composition.

The important scientific data to determine the origin of Phobos and Deimos are: global and local elemental abundances of Phobos (Laurence et al. 2019) with enough precision to distinguish chondritic or non-chondritic composition (including Martian components or not), the high resolution map of visible and near-infrared reflectance spectrra to explore the presence or absence of hydrated silicates on Phobos and Deimos (Barucci et al. 2021), and chemical, mineralogical and isotope composition of the returned samples to determine to determine whether Phobos is primordial solar system material or high-temperature heated processed material (Fujiya et al. 2021). If we succeed the remote sensing observations and return sample analyses, the origin and formation process of the Martian moons will be clarified within a few years from the sample return to the Earth expected in 2031.

References :

Barucci M.A. et al. (2021) Earth, Plan. and Space, 73, 211.

Fujiya W. et al. (2021) Earth, Plan. and Space, 73, 1.

Kuramoto K. et al. (2022) Earth, Plan. and Space, 74, 12.

Lawrence et al. (2019) Earth Space Science, 6, 2605.

Nakamura et al. (2021) Earth, Plan. and Space, 73, 227.

How to cite: Nakamura, T., Ikeda, H., Takeo, Y., Usui, T., Kuramoto, K., Working team, M. O., and Board, S.: MMX mission update and long-term operation plan in the whole mission period, EPSC-DPS Joint Meeting 2025, Helsinki, Finland, 7–13 Sep 2025, EPSC-DPS2025-22, https://doi.org/10.5194/epsc-dps2025-22, 2025.

The JAXA MMX (Martian Moon eXploration) mission will be launched in October 2026 to the Martian system to carry out three years observations of the Martian moons, and to bring back to Earth at least 10 g samples from Phobos. The primary goal [1] of the mission is to understand the origin of the Martian moons: Phobos and Deimos, for which two major hypothesis are still debated. Are the two satellites captured asteroids after the Mars formation ? Or are they results of a giant impact with Mars ? Laboratory analysis of returned samples will be key to answer these fundamental questions. The mission objectives in studying Martian moons are also to enlarge our knowledge of the Martian system and to constrain the processes of planet formation.

The onboard instruments [1] will allow the right selection of the two Phobos sampling site selection. The cameras (OROCHI, TENGOO and Cam-T) [2] will allow the safe selection for the landing sites, while the imaging spectrometer MIRS (MMX InfraRed Spectrometer) [3,4] and MEGANE (Mars-moon Exploration with Gamma rays and Neutrons) instrument [5] will be the key instruments for the compositional characterization, global chemical and mineralogical mapping, and to support the landing site selection.

At the arrival of the spacecraft into Mars system in 2027, MMX will observe Deimos by several fly-bys, and then it will be injected into Phobos co-orbit like a Martian Moon in orbit around Mars, in the so-called quasi-satellite orbits (QSOs). To obtain global mapping at different spatial resolutions with the cameras and MIRS, and to characterize the selected landing sites, the QSOs will be settled in the equatorial plane of Phobos with several decreasing altitude (High, Medium and Low), from 100km to 7km. The mapping at different resolutions by MIRS will be essential for a global characterization and evaluate the properties and geologic context of different materials to select the best landing sites. Observations at specific local times and phase angles will be also performed to study the surface temperature and its spatial and temporal variations. From these measurements, the surface thermal inertia of Phobos will be derived at the instrument spatial resolution. The multiple flybys of Deimos will allow to compare its surface composition to that of Phobos with observations at similar resolution.

The MIRS spectrometer [3,4], designed to accomplish the MMX’s scientific objectives, is a push-broom imaging spectrometer working in the spectral range 0.9 -3.6 µm. The measured spectral resolution is 21 nm up to 3.2 µm with SNR ≥ 100 in the region up to 3.2 µm. The instantaneous Field of View (iFoV) is 0.325-0.350 mrad, and the field of View (FoV) is +/-1.65°.

MIRS will characterize spectroscopically the global surface material distribution of Phobos at spatial resolutions better than 20 m, up to few meters at low altitude for the preselected landing sites and up to few cm for the two selected sampling sites. MIRS is expected to detect all possible present signatures (up to band depths of 3%) on the obtained spectra like anhydrous or hydrous silicate minerals, characterize the presence of water (ice) and to detect the presence of organic materials. The MIRS performances will allow to investigate on the composition like their aliphatic or aromatic nature, whether they are nitrogen-bearing or pure carbonate. MIRS will be able to measure the spectral radiance of the surface within the instrument footprint. Grain sizes and porosity will be constrained by thermal Inertia. Space weathering processes will be also investigated thanks to resolved spectral observations of small fresh craters and their ejecta. MIRS data associated with the on-board cameras and MEGANE instrument will give new insights on the surface characterization of these two moons. The unprecedent spatial resolution of MIRS will allow to search for heterogeneities that could be linked to Mars surface composition and it will allow to detect exogeneous material if present on the surface of Phobos. This will provide constrains on the transport mechanisms between Mars and the two moons and the eventually dichotomy between the sub and anti-martian hemispheres of Phobos.

MIRS will be used to support the selection of the two landing sites based on their grain size and composition, and will be able to observe during its descent phase down to an altitude of 400m. MIRS will be able to determine the surface composition of both Phobos and Deimos. This will allow us to decipher the origins of the two moons given that: i) the detection of phyllosilicates as well as of organics on their surface would imply that the origin of Phobos and Deimos is by a capture process, while ii) the detection of anhydrous silicates or spinels may suggest a high-temperature origin by impact, leading to a depletion of volatile elements and incorporation of Martian rocks (crust and mantle). In the assumption that Phobos formed in a giant impact, simulations [6] show that the impact could be much less energetic than the Moon-forming impact, with temperatures of the order of 2000 K. This temperature remains sufficiently high to produce a depletion in water, phyllosilicates and organic. Consequently a detection of presence of these materials (even in small quantities) by spectroscopy on the surface of Phobos will confirm the capture hypothesis.

High-accuracy laboratory analysis of volatile elements and isotopic ratios of returned samples from the two regions will give the final answer on the origin of Phobos.

Acknowledgements: MIRS is built at Paris Observatory in collaboration with CNES, four other French laboratories (LATMOS, LAB, OMP, IRAP), and close collaboration with JAXA and MELCO. MMX is developed and built by JAXA, with contributions from CNES, DLR, ESA and NASA.

References :

[1] Kuramoto K. et al. (2022) Earth, Plan. and Space, 74, 12.

[2] Kameda et al. (2021) Earth, Plan. and Space, 73, 218.

[3] Barucci M.A. et al. (2021) Earth, Plan. and Space, 73, 211.

[4] Barucci M.A. et al. (2025) Progress in Earth and Planetary Science, in press

[5] Lawrence et al. (2019) Earth Space Science, 6, 2605.

[6] Charnoz S. et al. (2025) Icarus, 434, 116462

How to cite: Barucci, M. A., Nakamura, T., Fornasier, S., Merlin, F., Beck, P., Doressoundiram, A., Gautier, T., Iwata, T., Poggiali, G., Sultana, R., Wargnier, A., and Yumoto, K.: To constrains the origin of Phobos and Deimos by MIRS/MMX imaging spectrometer , EPSC-DPS Joint Meeting 2025, Helsinki, Finland, 7–13 Sep 2025, EPSC-DPS2025-268, https://doi.org/10.5194/epsc-dps2025-268, 2025.

Introduction

The Martian Moon eXploration (MMX) mission by the Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency, JAXA,

is going to explore the martian moons Phobos and Deimos. Both moons will be investigated remotely from the mother spacecraft, that will also collect samples from the surface of Phobos. There will also be a small rover, IDEFIX, which will be delivered to Phobos´ surface and make in-situ investigations.

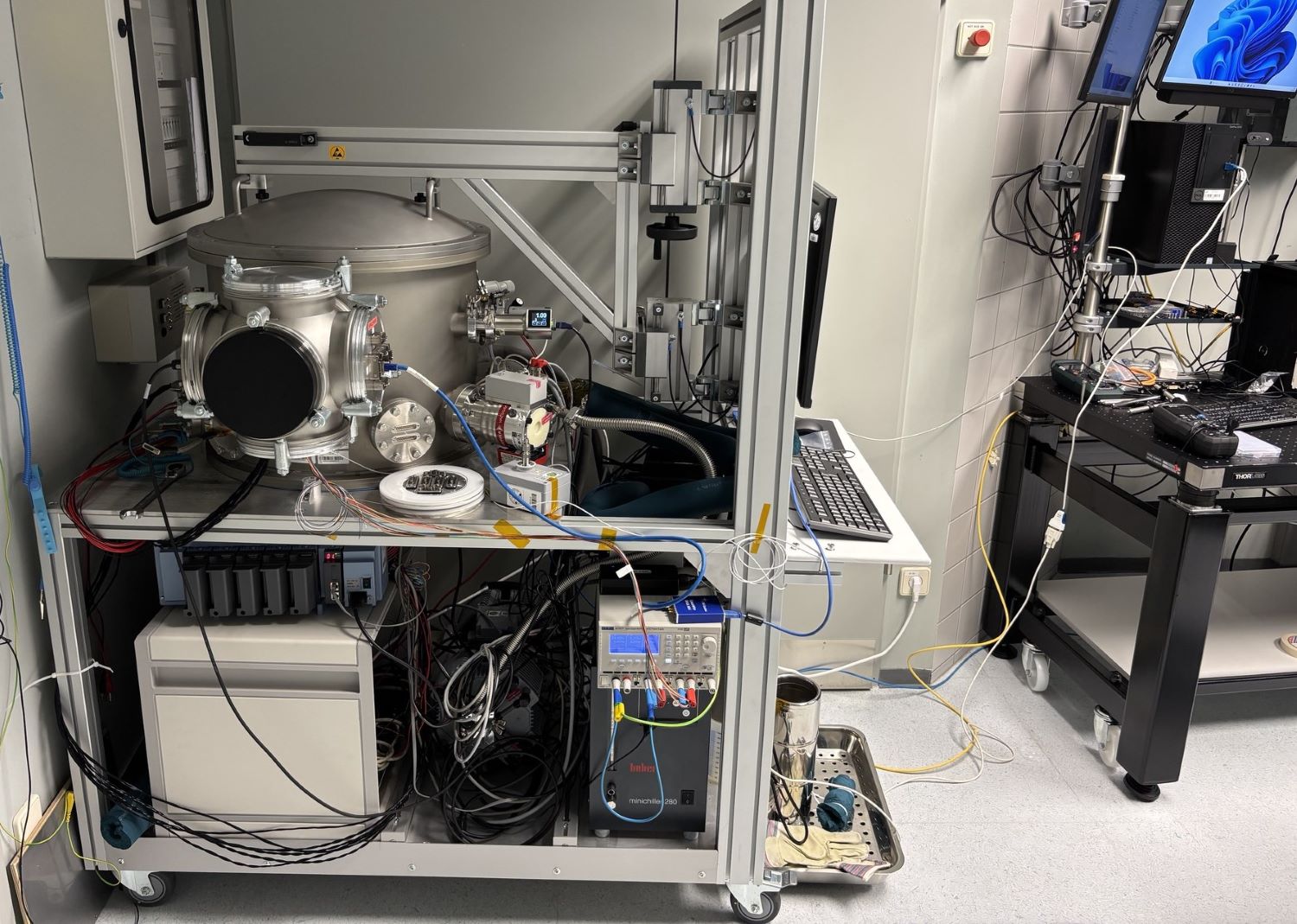

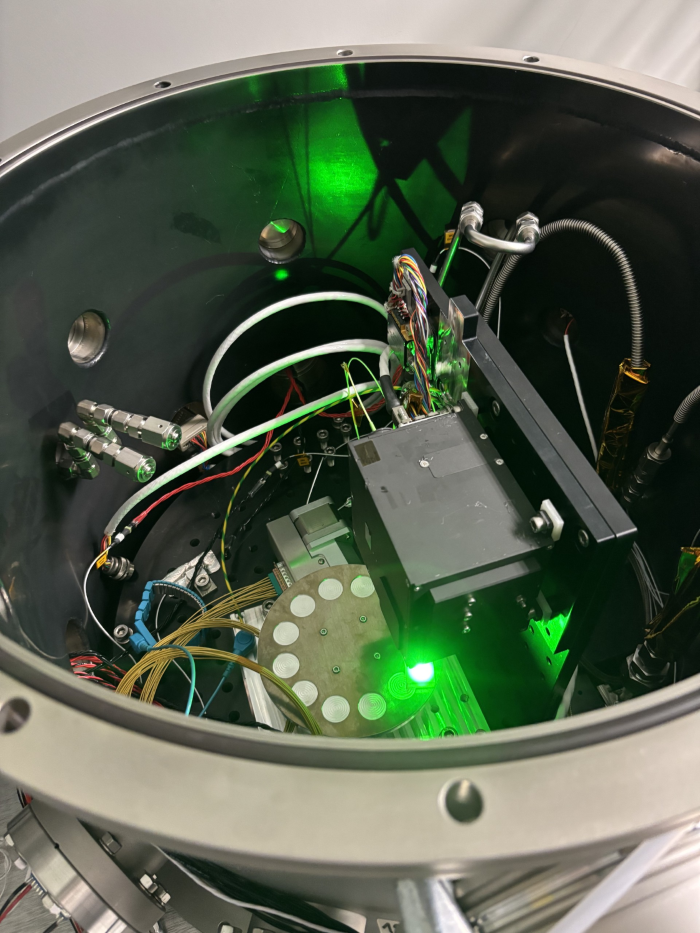

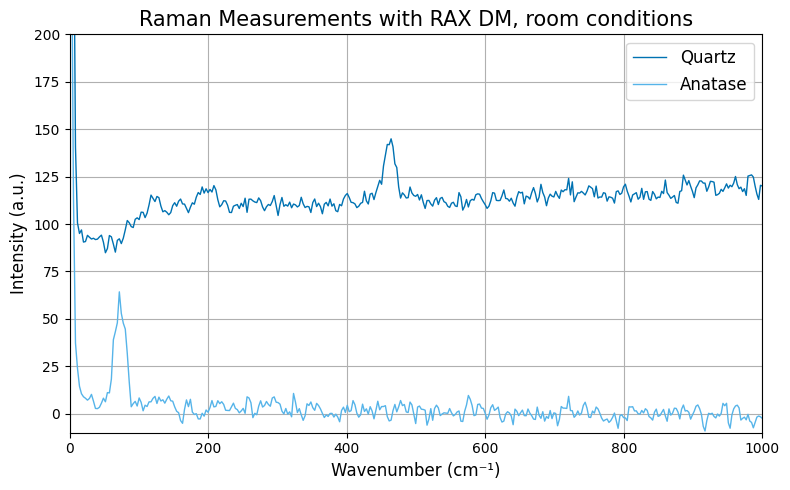

The Rover carries a scientific payload of four instruments: RAX, a Raman spectrometer, NavCam, a stereo pair of cameras looking ahead to image the terrain and also support navigation, miniRAD, a radiometer, and two WheelCams looking at the wheel-surface interface, and thus investigating the properties and dynamics of the regolith. The camera pairs will serve for both, technological and scientific needs [1,2].

The Rover is a contribution by the Centre National d’Etudes Spatiales (CNES) and the German

Aerospace Center (DLR) with additional contributions from INTA and Univ. Valladolid (Spain) and Univ. Tokyo and JAXA.

IDEFIX design and payload

The rover with an allocated mass of 29.1 kg, (including the mechanical support system (MECSS) and communications system, which will stay on the main spacecraft) is based on a carbon fiber structure, a locomotion system with four individually controlled wheels and a power system with a solar generator and re-chargeable batteries.

The ground segments are established at CNES in Toulouse as well as at DLR in Cologne, Germany. All communications between the rover ground segment and the flight segment are linked via the MMX spacecraft and the JAXA ground segment and ground stations.

IDEFIX is accommodating four scientific instruments:

Navigation cameras NavCams, looking in front of the rover with a resolution of ~1 mm at 1 m distance. Besides of the scientific use, they are key for navigation and analysis of the rover location, attitude and locomotion.

Two WheelCams placed on the underside of the rover each aim at a different rover wheel. The WheelCam images of the surface will be used to characterize the regolith particles (e.g., size distribution, morphological characteristics).

The Raman spectrometer RAX is able to analyse the mineralogy on a spot about 8 cm underneath the rover chassis. Heterogeneity of surface grains can be determined and the mineralogy of the material, measured in-situ will complement orbital spectroscopic data and will be important for putting in context the samples which will be returned to Earth.

The radiometer miniRAD will investigate the surface temperature and surface thermo-physical properties of Phobos by measuring the radiative flux emitted in the thermal infrared wavelength range. The measurements will also constrain porosity, surface roughness, and emissivity of the surface material.

Figure 1 shows the rover design, fully deployed in the on-Phobos configuration. Figure 2 shows the Flight model before integration to the main spacecraft.

Fig. 1. IDEFIX in on-Phobos configuration with deployed solar generator (image: CNES)

Fig. 2. IDEFIX Flight model shortly before integration to the main spacecraft

IDEFIX project status, one year before launch

The IDEFIX rover was delivered to JAXA in February 2024, after undergoing its environmental test program in Europe. It is now attached to the main spacecraft, where tests of the complete MMX system are performed at MELCO in Kamakura. Thermal Vacuum tests have been finalized in spring 2025. The overall test program for IDEFIX is performed both, with the flight model, attached to the MMX spacecraft, but also for operational and planning preparation with a representative “flat rover” at CNES in Toulouse.

The launch of MMX is now foreseen for October 2026, arrival at the martian system in 2027 and landing of the rover in late 2028 or early in 2029, after a landing site selection exercise.IDEFIX will be released from an altitude of about 40 m, fall to the surface, upright itself and drive and carry out scientific investigations for about 100 days.

References: [1] Michel, P. et al., Earth, Planets and Space, 74:2, 2022; [2] Ulamec, S. et al., Acta Astron., Vol. 210, pp. 95-101, 2023

How to cite: Ulamec, S., Michel, P., Grott, M., Schröder, S., Hübers, H.-W., Cho, Y., Prieto-Ballesteros, O., Murdoch, N., Vernazza, P., Biele, J., Tardivel, S., Krause, C., Grundmann, J.-T., Baroukh, J., Grebenstein, M., and Miyamoto, H.: IDEFIX - The MMX Phobos Rover: One year before launch, EPSC-DPS Joint Meeting 2025, Helsinki, Finland, 7–13 Sep 2025, EPSC-DPS2025-584, https://doi.org/10.5194/epsc-dps2025-584, 2025.

Introduction: The Mars-moon Exploration with GAmma rays and NEutrons (MEGANE) investigation will use both a Gamma-Ray Spectrometer (GRS) and Neutron Spectrometer (NS) to measure the elemental composition of Mars’ moon Phobos [1]. The MEGANE investigation is funded by NASA to participate in the Martian Moons eXploration (MMX) mission led by the Japanese Aerospace Exploration Agency (JAXA). MEGANE has three primary science goals, which are: 1) Determine whether Phobos is a captured asteroid or the result of a giant impact; 2) Study surface processes on airless bodies in Mars’ orbit; 3) Support MMX sample return by informing landing site selection and documenting the context of the MMX returned samples. Specifically, MEGANE will use gamma-ray and neutron spectroscopy to measure the concentrations of the following elements at Phobos’ surface: H, O, Mg, Si, K, Ca, Fe, and Th. MEGANE flight hardware has been delivered to the MMX spacecraft contractor, Mitsubishi Electric Corporation (MELCO), has been installed on the MMX spacecraft exploration module, and has completed its first full functional test on the spacecraft. Here, we present the status of the MEGANE investigation as the MMX mission proceeds towards launch in the fall of 2026.

MEGANE Instrumentation: MEGANE has three hardware components (Figure 1): the GRS, NS, and the Data Processing Unit (DPU). The GRS consists of a high-purity Ge (HPGe) gamma-ray sensor surrounded by a borated plastic scintillator that serves as an active anticoincidence shield (ACS) and fast neutron detector. The NS consists of two 3He sensors that measure thermal (neutron energy En < 0.4 eV) and epithermal neutrons (En > 0.4 eV). The DPU provides power, commanding, signal processing and data throughput functions. The MEGANE flight model (FM) hardware was delivered to JAXA and MELCO in December 2023. After a series of post-delivery tests to show that the hardware met requirements (Figures 2–4), the three components were handed over to JAXA and installed on the MMX exploration module in the spring of 2024.

MEGANE Post-delivery Activities: After the installation of the MEGANE components on the MMX exploration module, a series of increasingly complex tests were carried out to exercise various parts of the MMX (and MEGANE) hardware. These tests culminated with an initial electrical test that exercised the full functionality of MEGANE while installed on the MMX spacecraft with the other MMX instruments operating. With this test, we demonstrated full instrument functionality that meets performance requirements. This performance includes a demonstration of all commanding capabilities, operation of all sensors, and exercising the complete data pipeline flow that goes from the spacecraft to JAXA to the MEGANE Science Operations Center at Johns Hopkins Applied Physics Laboratory. During this test, the HPGe sensor had higher than expected leakage current, and we are working various mitigations to reduce this leakage current and its impact to GRS performance.

The MEGANE hardware is currently participating in various spacecraft environmental tests, including a recently completed thermal-vacuum test, as well as system level vibration and electromagnetic interference tests planned for later in 2025. Final post-environmental MEGANE testing is planned to take place at the Tanegashima launch site prior to launch in the fall of 2026.

In addition to spacecraft testing, the MEGANE team is working closely with JAXA colleagues to carry out planning for spaceflight operations of the MEGANE instrumentation [3]. MEGANE composition measurements will be conducted during two separate low-altitude operations phases – one phase prior to landing and one after landing. The primary composition measurements will be obtained when the MMX spacecraft is at an altitude of less than one Phobos radius. Other MEGANE operations include background measurements when the spacecraft is at high altitudes above Phobos, charged particle environment monitoring with the ACS and NS sensors, and an initial hardware checkout during the Earth-to-Mars cruise phase.

Summary: MEGANE flight model hardware has been delivered to and installed on the MMX spacecraft, and has demonstrated its full operation. Final operations planning and system testing is ongoing prior to the fall 2026 launch of MMX.

References: [1] Lawrence et al., Earth and Space Science, 6, 10.1029/2019EA000811, 2019; [2] Peplowski et al., NIM A, 10.1016/j.nima.2025.170542; [3] Kuramoto et al., Japan Geosci. Union Meeting 2025, PPS09-01, 2025.

How to cite: Lawrence, D. and the MMX MEGANE Team: The Mars-moon Exploration with GAmma rays and NEutrons (MEGANE) Investigation for the Martian Moon eXploration (MMX) Mission: Progress Towards Launch, EPSC-DPS Joint Meeting 2025, Helsinki, Finland, 7–13 Sep 2025, EPSC-DPS2025-1071, https://doi.org/10.5194/epsc-dps2025-1071, 2025.

The Martian Moons eXploration (MMX, JAXA) mission aims to perform the first sample return from Phobos and deploy a rover (IDEFIX, CNES/DLR) to explore the surface. The main objective of MMX is to decipher the origin of Phobos. Consequently, selecting the optimal sampling site in order to maximize the likelihood of retrieving material representative of Phobos’ composition and deploying IDEFIX in a dynamically safe environment are both critical for the success of the mission. In this context, understanding the surface dynamics of Phobos is essential for optimizing site selection, guiding rover operations, and interpreting the geological origin of collected samples.

Our work combines a physics-based analysis of Phobos' orbital dynamics with a surface-constrained trajectory model to assess regolith mobility and terrain stability. The core philosophy of our approach is to treat the moon’s surface as a dynamically evolving environment, shaped not only by impacts and thermal cycling but also by continuous external forces (i.e., centrifugal, tidal, and Coriolis) arising from its orbital motion and near-synchronous rotation around Mars.

We begin from the orbital dynamics analysis, which provides the instantaneous acceleration field across Phobos’ surface throughout its eccentric orbit. These accelerations are derived from a dynamical model that incorporates instantaneous tidal interactions with Mars, Phobos’ spin state, and its complex geometry.

From the resulting dynamic slope field, we extract three key indicators for landing site evaluation, integrating both short-term dynamical mobility and long-term surface behavior:

- Maximum dynamic slope: indicates whether a terrain becomes unstable at any point during the orbit.

- Mean dynamic slope: reflects long-term equilibrium and serves as a proxy for the local repose angle.

- Temporal variability of the dynamic slope: highlights regions subject to cyclic changes in surface stability, potentially enhancing regolith mobility even in otherwise stable areas.

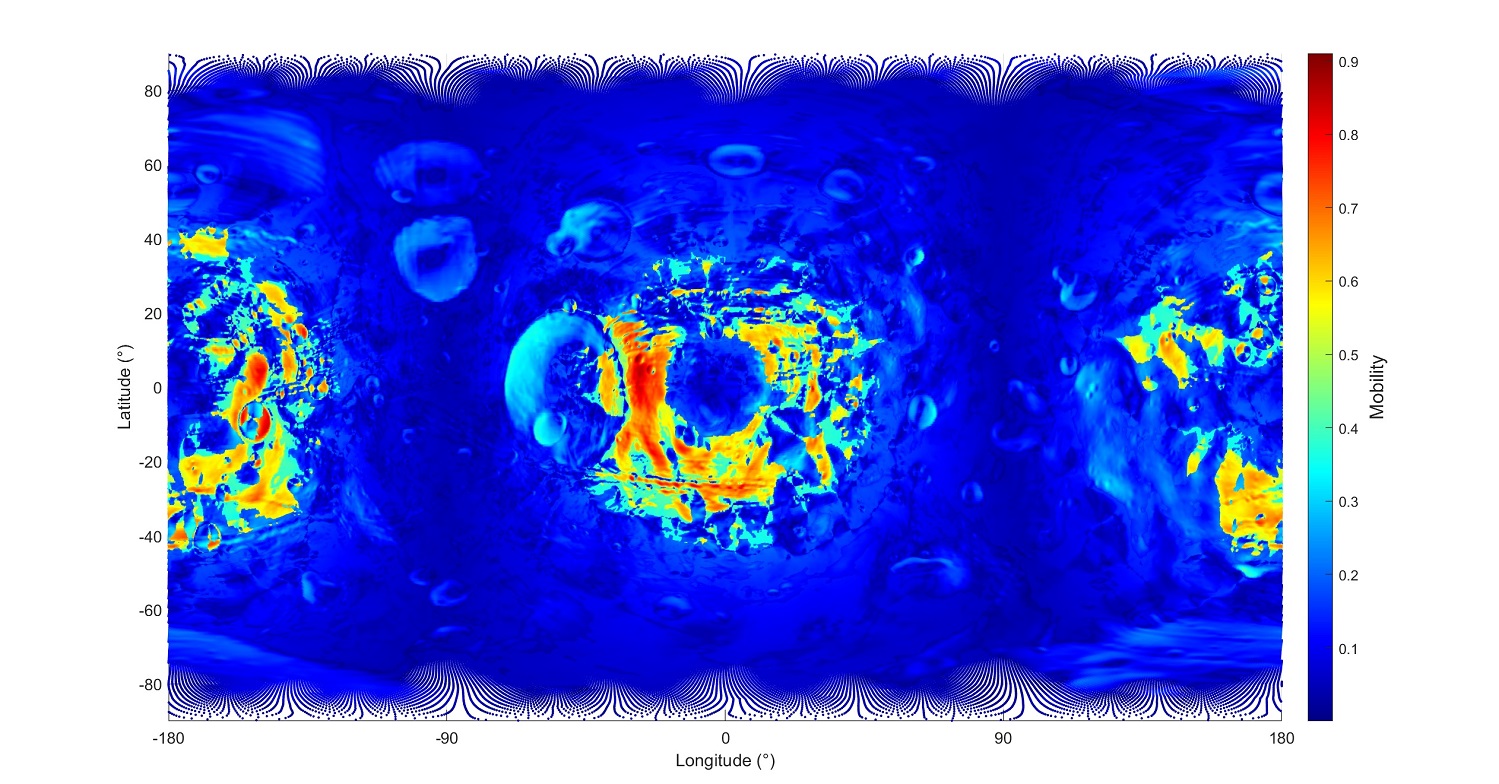

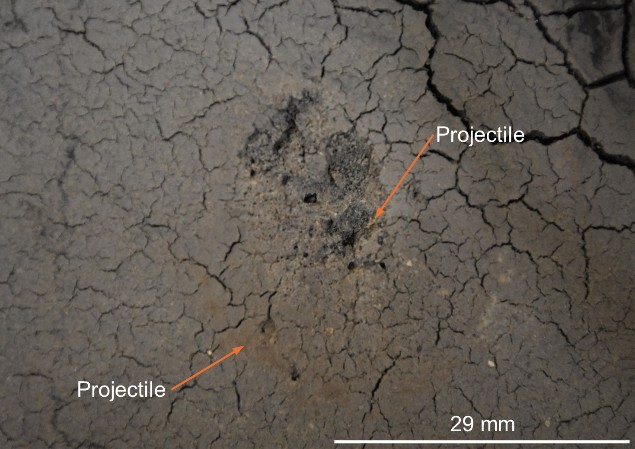

Based on these indicators, we have constructed a normalized map to assess the potential mobility of surface regolith across Phobos (see Figure 1). This map integrates the maximum, mean, and temporal variability of the dynamic slope, offering a synthetic view of terrain stability and its susceptibility to material transport. It provides a valuable basis for evaluating both long-term accumulation zones and areas prone to transient motion, supporting the strategic selection of sampling and landing regions.

Figure 1. Normalized mobility index across Phobos’ surface, derived from the combination of dynamic slope amplitude, average, and variability along the orbit. The mobility index ranges from 0 (minimum expected material motion) to 1 (maximum susceptibility to regolith displacement).

We then simulate regolith transport across a high-resolution shape model of Phobos (Ernst et al., 2023). These simulations serve two main purposes. First, they allow us to identify low-mobility regions where regolith tends to accumulate, and high-mobility regions where surface material may be periodically transported or lost, and thus less affected by space weathering. This supports the selection of landing zones that are both safe and scientifically valuable. Second, we reverse-integrate trajectories from selected target points (e.g., candidate sampling sites) to identify the potential source areas of deposited material. This source region mapping provides critical context for interpreting in situ analyses by linking samples to their geological and dynamical origin.

Our methodology offers a robust decision-support tool for MMX mission planning, helping to:

- Select landing sites that are both dynamically stable and compositionally representative.

- Guide rover navigation toward accessible, diverse sampling areas.

- Inform post-return analyses by linking samples to their surface origin and transport history.

As of May 2025, the MMX landing site has not yet been finalized. Within the currently proposed candidate zones, some appear better suited to retrieving material representative of the surface regolith, while others may offer access to more pristine, rock-derived samples. For IDEFIX, a subset of these zones combines geological diversity with dynamical safety, offering promising terrain for in situ exploration.

This study demonstrates how physics-based modeling of regolith dynamics can directly support the planning, execution, and interpretation of planetary surface missions. The integration of orbital and surface mechanics offers a predictive framework not only for choosing where to land and sample, but also for uncovering the dynamical history behind the regolith, and identifying those regions most likely to preserve material representative of Phobos’ global composition, crucial for constraining the moon’s origin.

Acknowledgements: SC is supported by the French ANR project Roche, number ANR-23-CE49-0012, and French Space Agency (CNES). IH is supported by grant No. PID2020-116846GB-C22 by the Spanish Ministry of Science and Innovation/State Agency of Research MICIU/AEI/10.13039/501100011033 and by ‘‘ERDF A way of making Europe’’.

How to cite: Herreros, I. and Charnoz, S.: Surface Mobility and Regolith Transport Analysis to Support MMX Landing Site Selection and Sampling Strategies on Phobos, EPSC-DPS Joint Meeting 2025, Helsinki, Finland, 7–13 Sep 2025, EPSC-DPS2025-561, https://doi.org/10.5194/epsc-dps2025-561, 2025.

Please decide on your access

Please use the buttons below to download the supplementary material or to visit the external website where the presentation is linked. Regarding the external link, please note that Copernicus Meetings cannot accept any liability for the content and the website you will visit.

Forward to presentation link

You are going to open an external link to the presentation as indicated by the authors. Copernicus Meetings cannot accept any liability for the content and the website you will visit.

We are sorry, but presentations are only available for users who registered for the conference. Thank you.

Introduction. The origin of the Martian moons remains a debated topic within the scientific community. Two leading scenarios are commonly considered: the capture of an asteroidal object [1-2] and a giant impact between proto-Mars and a large body [3-5]. The debate arises from the red-sloped spectra, and the primitive and dark appearance of Phobos [6-15], resembling a D-, P- or T-type asteroid [16]. This is contradicted by the orbital parameters [17], the MIR/TIR spectra [18-20] and a possible presence of a 1 µm absorption [6], all suggesting an impact origin. Another debated topic is Phobos’ color dichotomy that characterizes the satellite surface, first described by [6]. The blue unit is associated to the eastern rim of Stickney crater (9 km across), while the red unit characterizes the rest of the surface. The blue unit has a higher reflectance in the VIS [21]. Since the latter is prominent near the impact site, it is hypothesized to consist of ejected material from Stickney. In contrast, the red unit is an older, space weathered material.

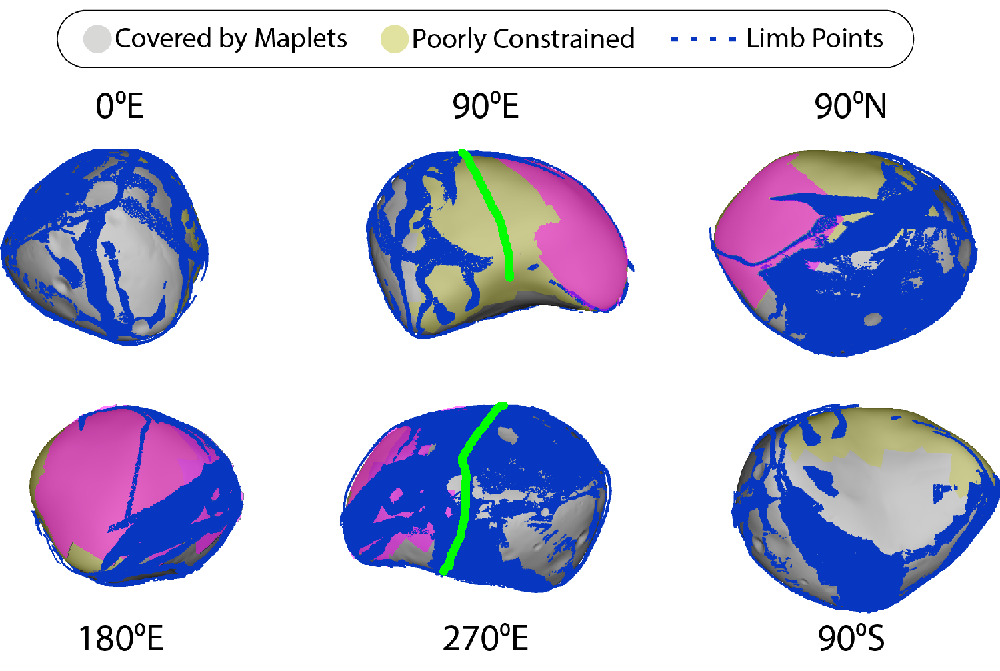

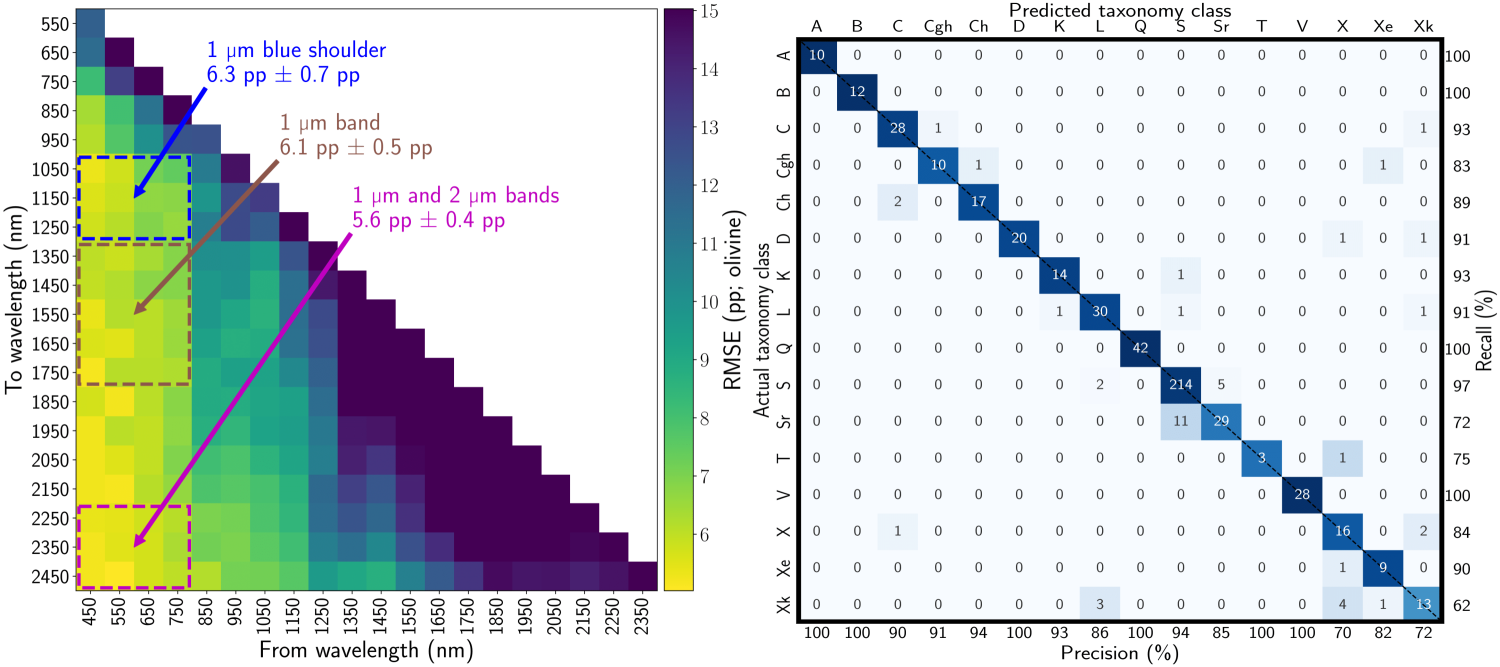

In this work we have analyzed three MeX/OMEGA (Observatoire pour la Minéralogie, l’Eau, les Glaces et l’Activité, [22]) datacubes in the spectral range 0.4 µm - 2.5 µm. The aim is to perform detailed spectroscopic analysis to understand composition and mineralogy of Phobos.

Methods and Results. The data underwent a geometric and photometric correction. For the latter, we used the Lommel-Seeliger Function, a simplified photometric law from the Hapke Theory [23] which performs very well for surfaces dominated by single scattering (i.e. dark surfaces) [11,13].

Regions of Interest (ROIs) were identified across the three datacubes, to analyze the blue and red unit spectral properties as well as to describe the transition between them.

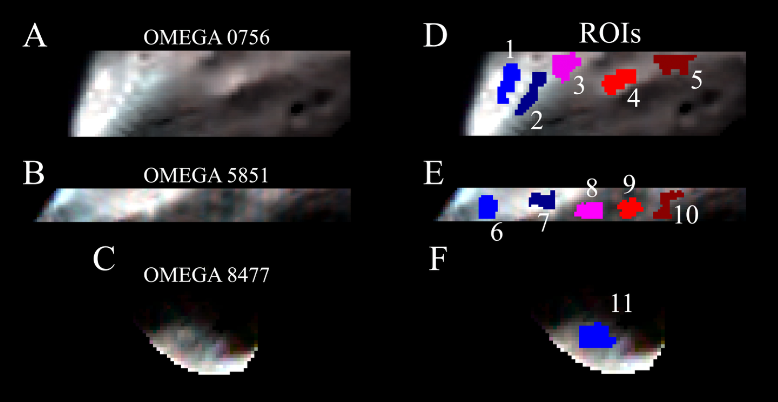

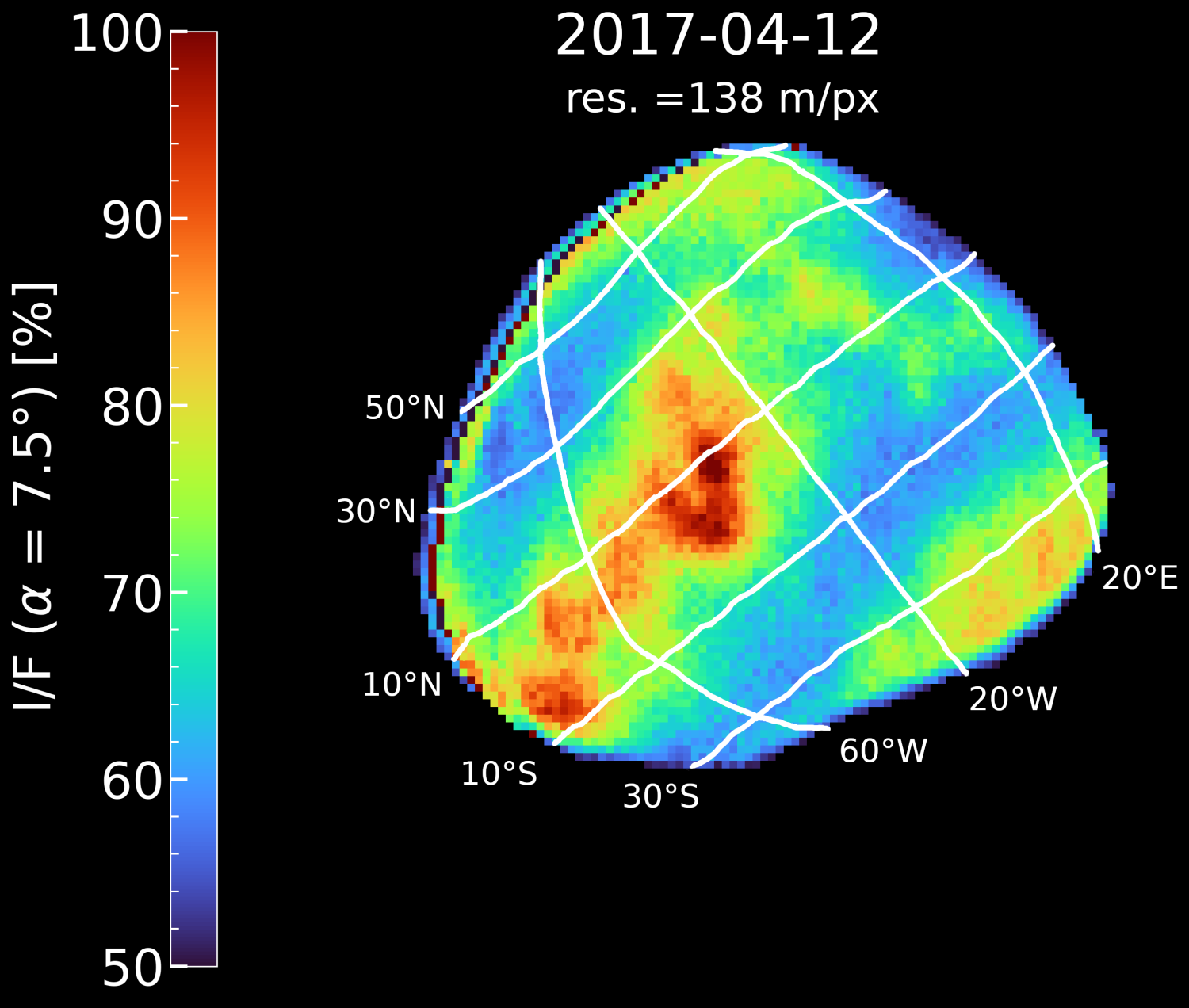

Figure 1: Set of ROIs identified across the three datacubes.

In Fig.1D-E-F the locations of all identified ROIs are shown. As illustrated FIG.1A, the cube 0756 captured a portion of the inner region of the Stickney crater where we identified the ROI 1 and the blue unit close to the rim of Stickney, where ROI 2 was selected. The remaining area is occupied by the red unit. ROI 3-4-5 were identified progressively farther from the blue unit to examine spectral transitions.

As seen in Fig.1B, cube 5851 captures a larger portion of Stickney interior, where ROI 6-7 have been identified, while ROI 8-9-10 have been selected with the same approach adopted for the ROI 3-4-5.

Finally, for orbit 8477 (Fig.1C) a single large ROI has been selected due to the considerable noise of this dataset.

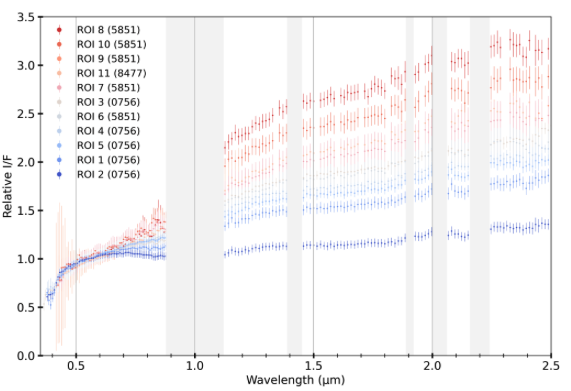

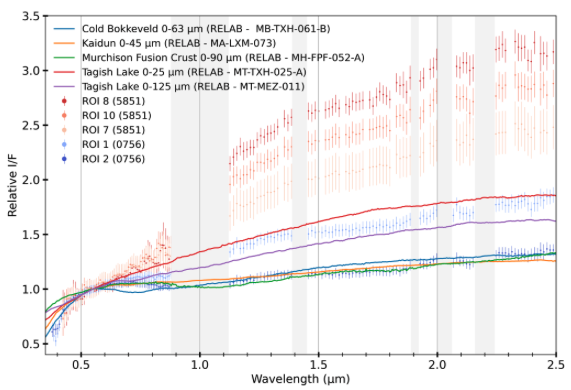

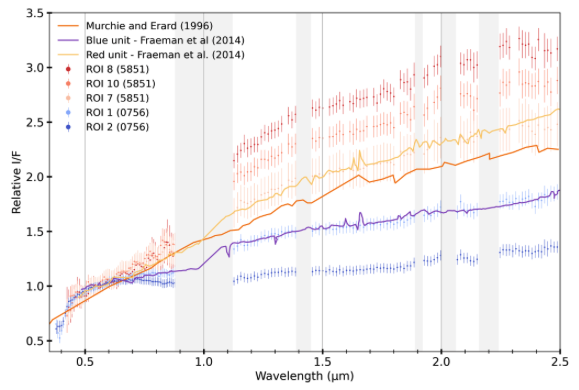

In Fig.2 the mean extracted and normalized spectra are presented: it is possible to notice the gradual transition in slope from the blue unit spectra to the redder regions. The error bars account for both standard deviation and instrumental errors, while the gray bands are wavelength ranges where bad bands are present. The gradual spectral transition of Phobos suggests an increase degree of mixing between the blue and the red unit as we approach to the blue unit. In addition, one may notice the absence of strong absorption features, which makes difficult to diagnostic the mineralogy.

The only subtle absorption that we identified appears in ROI 2, near 1 µm. If confirmed, it would trace presence of olivine and pyroxene. However, this remains a tentative suggestion due to the instrumental decrease in sensitiveness at this wavelength range.

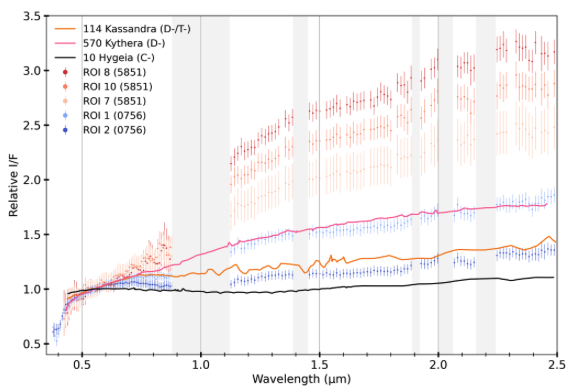

In Fig.3 we present the best match with asteroid spectra. While the blue unit seem to be consistent with the T-/P- type of asteroid, the transition/red unit is best fitted with the D-type asteroid.

Figure 2: Set of mean spectra extracted.

Figure 3: Comparison with mean Tholen spectra [26].

The meteorite comparison supports the asteroid comparison’s results (see Fig.4). Indeed, the Tagish Lake (TL) meteorite, a D-type asteroid analog [25], matches the Phobos transition/red unit. For the blue unit, the best analog found include Kaidun, a Phobos analog by [27], the Murchison fusion crust, also proposed by [9] as a Phobos analog, and cold Bokkeveld. Such meteorites consist of carbonaceous chondrites, i.e. primitive material.

Figure 4: Comparison with meteorites spectra.

Finally, we present the comparison with results present in the literature (see Fig.5). While the red unit of [6] and [11] are consistent with our dataset, the blue unit of [11] seems to match the transitional unit. This indicates that the ROI 2 mean spectra may be one of the bluest spectra of Phobos ever obtained.

Figure 5: Comparison with relevant literature spectra.

References. [1] Singer, 2003, 6th Int. Conf. on Mars, page 3063; [2] Hansen, 2018 MNRAS, 475(2):2452–2466; [3] Craddock et al. (2011), Icarus, 211, 1150–1160; [4] Rosenblatt and Charnoz (2012), Icarus, 221, 806–815; [5] Hyodo et al. (2017), ApJ, 845, 125–132; [6] Murchie and Erad (1996), Icarus, 123, 63–86; [7]Rivkin, A et al. (2002), Icarus, 156, 64; [8] Pajola et al. (2012), MNRAS, 427, 3230; [9] Fraeman et al. (2012), J. Geophys. Res. Planets, 117; [10] Fraeman et al. (2014), Icarus, 229, 196; [11] Pajola et al. (2018), Planet. Space Sci., 154, 63; [12] Takir et al. (2022), Icarus, 371, 114691; [13] Fornasier et al. (2024), Astron. Astrophys., 686, A203; [14] Poggiali et al. (2022), MNRAS, 516, 465; [15] Wargnier et al. (2023), MNRAS, 524, 3809; [16] Bus, S. J. & Binzel, R. P. 2002, Icarus, 158, 146; [17] Jacobson et al. (2014), Planet. Space Sci., 102, 35; [18] Roush et al. (2000), Lunar Planet. Sci. Conf., 1598; [19] Giuranna et al. (2011), Planet. Space Sci., 59, 1308; [20] Glotch et al. (2018), J. Geophys. Res. Planets, 123, 2467; [21] Thomas et al. (2011), Planet. Space Sci., 59, 1281; [22] Bibring et al. (2004), Earth Space Planets, 1240, 37–49; [23]Hapke, 2012, Theory of Reflectance and Emittance Spectroscopy, Cambridge Univ. Press; [24] Acton et al. (1996), Planet. Space Sci., 44, 65; [25] Hiroi et al. (2001), Science, 293, 2234; [26] Tholen, D. J. 1984, PhD thesis, University of Arizona, USA; [27] Ivanov et al. (2004), Solar System Res., 38.2, 97–107;

How to cite: Beccarelli, J., Pajola, M., Munaretto, G., Lucchetti, A., Poggiali, G., Simioni, E., Tusberti, F., Rossi, C., Fornasier, S., Barucci, M. A., and Brucato, J. R.: Phobos 0.4 – 2.5 μm spectral analysis of the red and blue units through the MarsExpress/OMEGA dataset., EPSC-DPS Joint Meeting 2025, Helsinki, Finland, 7–13 Sep 2025, EPSC-DPS2025-787, https://doi.org/10.5194/epsc-dps2025-787, 2025.

Introduction

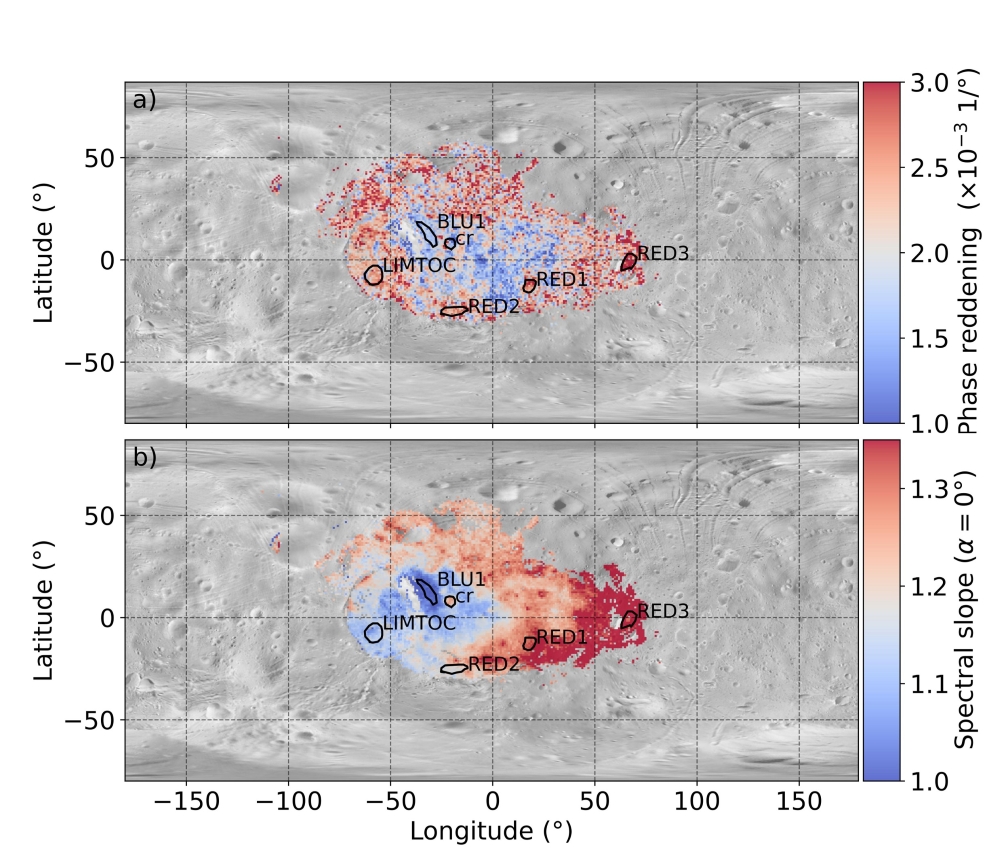

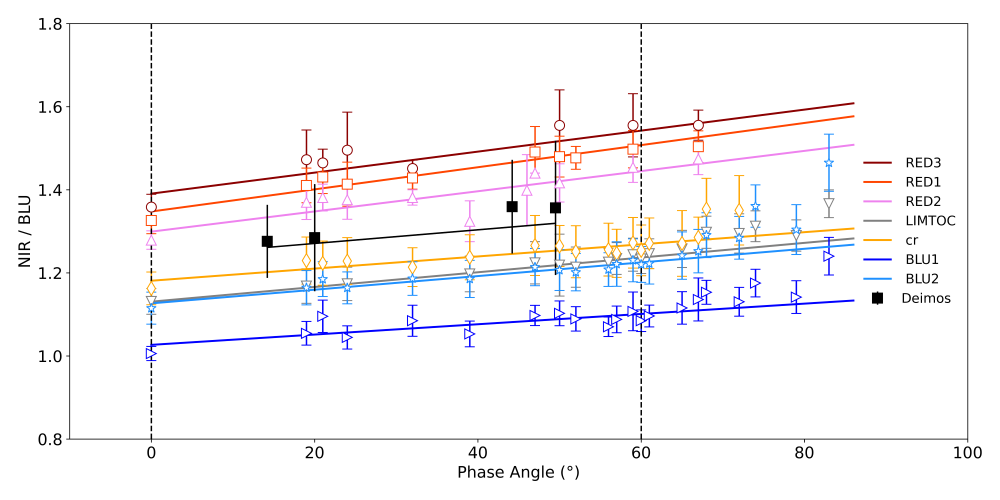

Phobos and Deimos are the two moons of Mars. Despite decades of observations, their origin is still debated, with hypotheses proposing either capture scenarios involving primitive asteroid-like bodies [1,2] or in-situ formation from impact-generated debris around Mars [3-5]. Previous studies revealed that Phobos has a spectrally heterogeneous surface consisting primarily of a "Red" unit and a spectrally distinct "Blue" unit near the Stickney crater [6-9]. Initially, the Blue unit was considered Stickney’s ejecta, but an exogenous (external) origin cannot be ruled out [10,11]. Deimos, on the other hand, appears spectrally uniform and closely resembles Phobos’s red unit [8]. Photometric analyses of the Martian moons are largely focused on Phobos ([2] and references therein), while Deimos is less studied [12]. One photometric properties of particular interest is phase reddening, i.e. the increase in spectral slope with phase angle attributed to multiple scattering, surface roughness at the sub-micron level, and space-weathering [13-15]. Its investigation helps to constrain the physical properties, in terms of particle size and roughness, of the martian moons surfaces. The Colour and Stereo Surface Imaging System (CaSSIS) is a stereo-camera on board the ExoMars/TGO satellite [16]. It provides images of the Martian surface in 4 filters centered at 499.9 nm (BLU), 675.0 nm (PAN), 836.2 nm (RED) and 936.7 nm (NIR). We present the analysis of the CaSSIS observations of the Martian Moons, the first characterisation of the spatial distribution of phase reddening on Phobos and its variability among specific geological units. In addition, we provide the first estimate of the Deimos global phase reddening and perform a comparative analysis with Phobos.

Fig. 1. a) Phase reddening and b) zero phase angle NIR/BLU spectral slope spatial distribution overlain on the Phobos Viking global mosaic. Black polygons labels indicate the name and position of the ROIs

Data & Methods

We analyse 35 CaSSIS 4 band observations of Phobos and 4 of Deimos, spanning phase angles of 0.8° − 83.0° and 14.2° − 49.5° and spatial resolution of ≈ 60-120 m/px and ≈ 200-300 m/px, respectively. Since Deimos has very small spectral variability we opted for a very simple and straightforward approach and collected the global average NIR/BLU filter ratio (as a proxy for spectral slope) and phase angle for all 4 observations and fitted this dataset with a linear model, which parameters allowed to estimate the global Deimos zero-phase angle spectral slope (model intercept) and the global Deimos phase reddening coefficient (model linear term). Instead, since for Phobos we have much more observations, we also analysed the spatial distribution of phase reddening and spectral slopes. This requires a different approach. We defined a 1°x1° resolution latitude-longitude grid with extent −90◦ + 90◦ and −180°+ 180°. For each grid point, we collected data (i.e., NIR/BLU and phase angle) from all the observations covering that location and fitted this dataset with a linear model, to obtain maps of phase reddening and zero phase spectral slope (Fig. 1). To analyse specific locations of Phobos with higher accuracy, we defined regions of interest (ROIs, Fig. 2) and repeated the fit with all data from such ROIs. In particular, we choose ROIs to represent different stages of regolith maturity, based on the high-resolution images and geologic map presented [10]. The "RED1" to "RED3" ROIs are picked on the Red Unit and represent the oldest and most mature surface of Phobos. "LIMTOC" and "BLU2" are relatively fresher and sample the Limtoc crater and the blue unit. The "cr" and “BLU1" ROI are the freshest units and post-date the Blue unit.

Fig. 2. Phase reddening model fits to the Phobos ROIs and Deimos. Vertical dashed lines indicate the range of phase angles used for the fit.

Results and Conclusions

Our spatially resolved phase reddening and spectral slope maps of Phobos and their comparison with the Deimos phase reddening highlight that:

- A broad region on Phobos, that includes the blue unit, is characterised by lower phase reddening surrounded by a higher phase reddening surface.

-Deimos and older Phobos units (“RED1” to “RED3“ ROIs) have the highest phase reddening. Younger units (“cr” and “BLU1” ROIs) have the lowest phase reddening. Intermediate age units, such as Limtoc, have intermediate phase reddening. This is consistent with phase reddening on Phobos originating from sub-micron roughness added by npFe0 particles added by space-weathering, as occurs at the Moon.

-We exclude either a Deimos or Stickney ejecta origin for the Blue unit. Instead, an exogenous nature is consistent with our results.

- We provide the first estimate of Deimos phase reddening, which is comparable to the Phobos Red unit.

Acknowledgements

CaSSIS is a project of the University of Bern and funded 240 through the Swiss Space Office via ESA’s PRODEX programme. The instrument hardware development was also supported by the Italian Space Agency (ASI) (ASI-INAF agreement no.2020-17-HH.0), INAF/Astronomical Observatory of Padova, and the Space Research Center (CBK) in Warsaw. Support from SGF (Budapest), the University of Arizona (Lunar and Planetary Lab.) and NASA are also gratefully acknowledged. Operations support from the UK Space Agency under grant ST/R003025/1 is also acknowledged. This work has been developed under the ASI-INAF agreement n. 2024-40-HH.0

References

[1] Pajola, M. et al. 2012, MNRAS, 427, 3230

[2] Fornasier, S. et al. 2024, A&A, 686, A203

[3] Rosenblatt, P. 2011, A&A Rev., 19, 44

[4] Craddock, R. A. 2011, Icarus, 211, 1150

[5] Hyodo, R. et al., 2017, ApJ, 845, 125

[6] Murchie, S. & Erard, S. 1996, Icarus, 123, 63

[7]Fraeman, A. A. et al. 2012, JGR:Planets, 117, E00J15

[8]Fraeman, A. A. et al. 2014, Icarus, 229, 196

[9]Pajola, M. et al. 2018, PSS, 154, 63

[10] Basilevsky, A. T. et al. 2014, PSS, 102, 95

[11] Takir, D. et al. 2017, AJ,153, 31

[12] Pang, K. D., et al. 1983, JGR:Planets,88, 2475

[13] Sanchez, J. A., et al. 2012, Icarus, 220, 36 300

[14]Sato, H. et al. 2014, JGR:Planets, 119, 1775

[15]Schröder, S. E. et al. 2014, Icarus, 239, 201

[16] Thomas, N. et al. 2017, SSR, 212, 1897

How to cite: Munaretto, G., Pajola, M., Beccarelli, J., Cremonese, G., Lucchetti, A., Re, C., Tullo, A., Almeida, M., Read, M., Mason-Piercy, K., Thomas, N., Patel, M. R., and Valantinas, A.: Phase reddening of Phobos and Deimos from TGO/CaSSIS observations , EPSC-DPS Joint Meeting 2025, Helsinki, Finland, 7–13 Sep 2025, EPSC-DPS2025-1483, https://doi.org/10.5194/epsc-dps2025-1483, 2025.

For more than 21 years, the Mars Express mission (MEx) has been orbiting the Martian system, acquiring data on Mars' surface and atmosphere, as well as on its two moons, Phobos and Deimos. The origin of the Martian moons remains a matter of debate. Deimos is the smallest of the two moons and orbits Mars at a much greater distance than Phobos. Previous photometric analyses [1] show that the surface of Deimos is smoother and more homogeneous than that of Phobos, but with overall similar photometric properties.

We analyzed images of Deimos taken with both the High Resolution Stereo Camera (HRSC) and the Super Resolution Channel (SRC) instruments. HRSC is a pushbroom camera with nine filters, including five panchromatic and four color filters (blue, green, red, and infrared), while the SRC is a framing camera with one panchromatic filter centered at 650 nm and covering from 400 to 900 nm [2,3]. The HRSC Deimos dataset is relatively limited with only 18 images available in each filter, acquired between January 2018 and January 2025, with a spatial resolution ranging from 390 m/px to 800 m/px. Conversely, the SRC dataset of Deimos contains more than 3500 images covering more than 20 years of observations, from October 2004 to December 2024. The spatial resolution varies from 85 m/px to 300 m/px, while the phase angle ranges from 0.06 to 120°. For the very first time, we have calibrated the absolute response of SRC using images of stars and Jupiter. We performed both disk-integrated and disk-resolved photometry. From the retrieved phase curve, we applied the Hapke IMSA [4] model to characterize the physical properties and the texture of the surface.

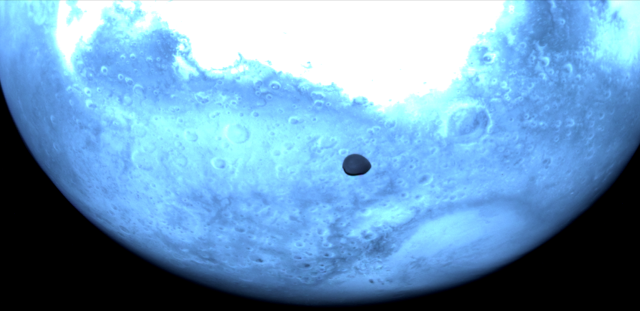

Figure 1: Disk-integrated phase curve of Deimos, compared with that of Phobos derived in [5] with the same HRSC filter.

The results obtained in the four HRSC color filters indicate that Deimos is photometrically similar to Phobos, while slightly brighter in the blue and green filters (Fig.1). Looking at the images, a bright region – corresponding to the streamers on the equatorial ridge – is evident (Fig. 2). Except for this feature, the surface of Deimos appears to be relatively homogeneous. In particular, the equatorial ridge, corresponding to higher geopotential height, is about 35% brighter (and up to 58%) than the average surface of Deimos. It is also notable that the craters (e.g., Voltaire (22°N; 3.5°E) and Swift (12.5°N; 358°E) craters) appear to exhibit no discernible increase in reflectance compared to the average surface. This contrasts with Phobos, where the crater rims are significantly brighter (up to 50%) than the average surface, at least in the area dominated by, or close to the blue unit. This suggests that the craters on Deimos are likely relatively old.

The derived Hapke parameters (considering a one-term Henyey-Greenstein function) have very similar values compared to those derived for Phobos in [5]: ω = 0.068 +/- 0.001, g = - 0.27 +/ 0.01, Bsh,0 = 2.14 +/- 0.14, hsh = 0.065 +/- 0.004, and θ = 19.4 +/- 0.1°. From these parameters we derived a porosity for the very first layer (typically few microns) of the surface of about 86%, indicating that the surface of Deimos is likely to be composed of complexly shaped grains and/or fractal aggregates. The parameters also suggest that Deimos has a strong opposition surge, which is mainly due to shadow hiding. We found that the coherent backscattering process is negligible on Deimos.

Based on the HRSC images, we have tentatively identified a blue unit on Deimos. This blue spectral behavior has already been noticed by [6]. Here we have shown that this blue unit is observed at least on the equatorial ridge (streamers). We found a decrease in the spectral slope of about 50% associated with this brighter region, compared to the average surface. The spectroscopic variations between the blue and red units on the two Martian moons are similar. This blue unit may be associated with changes in surface texture, such as grain size and porosity [7].

This work is the first extended study of the photometric properties of Deimos, in particular covering the opposition effect. The results are of significant interest for JAXA’s Martian Moon eXploration (MMX) mission [8], which will be launch in 2026 and return samples from Phobos to determine the origin of the Martian moons.

Figure 2: SRC Deimos image corrected by the Lommel-Seeliger disk-function.

Acknowledgements: The authors acknowledge the Centre National d’Etudes Spatiales (CNES) for the continuous support.

References: [1] Thomas et al. (1996),Icarus,123, 536-556 [2] Jaumann et al., PSS, 55, 928-952 [3] Oberst et al. PSS, 56, 473-491 [4] Hapke (2012), Cambridge University Press [5] Fornasier et al. (2024), A&A , 686, A203[6] Thomas et al. (2011), PSS, 59, 1281[7] Wargnier et al. (2025), accepted for publication in Icarus [8] Kuramoto et al. (2022), EPS, 74, 1, 12

How to cite: Wargnier, A., Fornasier, S., Simon, P., El-Bez--Sébastien, N., Tirsch, D., Matz, K.-D., Gautier, T., Doressoundiram, A., and Barucci, A.: Deimos photometric properties from Mars Express HRSC/SRC observations, EPSC-DPS Joint Meeting 2025, Helsinki, Finland, 7–13 Sep 2025, EPSC-DPS2025-276, https://doi.org/10.5194/epsc-dps2025-276, 2025.

Introduction: Phobos and Deimos importance as scientific target is growing up in the latest years due to an increasing interest in the planetary community on the origin and evolution of the two Martian moons. While the debate over whether these are captured asteroids [1] or the result of a catastrophic collision [2] is still ongoing, JAXA is preparing to launch in 2026 the Martian Moons eXploration (MMX) [3] sample return mission to study the two moons in detail and to collect a sample on the larger moon, Phobos, to be brought back to Earth in 2031. Along the spacecraft payload, a pivotal instrument to characterize the surface of the martian moons will be MMX InfraRed Spectrometer (MIRS) [4] giving access to the mineralogical composition of the surface and the possible presence of volatiles. The community's interest on these targets is confirmed by the decision of ESA to allow a fly-by of the moon Deimos with ESA's Hera spacecraft during its journey to the binary asteroid Didymos-Dimorphos. The probe acquired several images of the moon and Mars with its instruments, including the Hyperscout spectrophotometer and the TIRI thermal camera. In this growing interest, it becomes essential to exploit all the data we possess to prepare and support future explorations; in this light, the Mars Express (MEx) mission with its OMEGA and PSF spectrometers and HRSC multifilter camera represents an essential dataset for the study of the two martian moons. The other side of the problem, interpreting the effect of physical properties such as grain size, composition, porosity and space weathering, can only effectively approached with laboratory measurements. Measuring analog material such as meteorites and they primary component, minerals, can open the door to more complex and meaningful interpretation of the remote sensing observations.

Methods: In this contribution we will show how laboratory data are essential to data interpretation. In particular, the effect of grain size and composition, approached as single problem is already a promising way to remote sensing interpretation. But when these two features are studied in combination we have a key factor in understanding the physical processes and characteristics of a surface. In detail, we will show how selected range of grain size (i.e. < 100 µm or 100-200 µm) affects some of the main features of the infrared spectrum (slope, 2.7 µm band and Christiansen features, Reststrahlen bands and Transparency features in the mid-infrared range). Moreover, we will prove how a realistic grain size distribution derived from boulder and regolith size frequency can change the final outcome of the spectrum. These physical properties will also be studied through their link with composition mixing two or more components. Special attention will be focused on how which variable most influences the final spectrum and whether various types of environment (vacuum, temperature, irradiance...) can affect the final result. The presentation will go through the reanalysis of some data from the ESA Planetary Science Archives of the MEx mission, in particular we will show data from OMEGA and HRSC instrument, to fully exploit the potential derived from decades-long observations of moons and the planet Mars. These instruments, along with PFS thermal spectrometer, offer a unique point of view on the Martian moons allow to investigate the mineralogical nature of the surface.

Results and conclusion: We will show results from some recent lab work [5,6] in particular how grain size and dark material abundance can alter the slope or the depth of some fundamental bands like the OH-stretching at 2.7 µm. Moreover, these laboratory data will be used for the interpretation of recently published observations from various missions such as MEx-OMEGA [7] and TGO-NOMAD [8] and others. Moreover, additional MEx mission data from the ESA PSA [9] archive will be shown and compared with previous observations and laboratory data. In particular data from recent years will be exploited ton increase our dataset on different spectral range.

The goal of this work is to show the deep link that exists between remote sensing interpretation and laboratory measurements and how new advances can also be achieved by reanalysis of archival data. In the renewed interest in Martian moons we believe that a step forward on laboratory analogs can be made, leading in a big step forwards a more confident comparison with real surfaces. Therefore, only if the remote sensing data are combined with laboratory experiments on minerals and meteorites we can aspire to obtain an essential base knowledge for any future analysis aiming to interpret the nature of these enigmatic and elusive objects.

Acknowledgments: G.P. work on remote sensing data was supported by ESA Archival Research Visitor Programme. G.P. and J.R.B. acknowledge support from Italian Space Agency ASI-INAF agreement 2022-1-HH.0. M.A.B. and A.W. acknowledge support by Centre National d’Etudes Spatiales (CNES).

References: [1] Hyodo R. et al. (2018). ApJ, 860, 150 [2] Higuchi A. and Ida S. (2017). AJ, 153, 155 [3] Kuramoto K.et al. (2022) Earth Planets Space, 74, 12 [4] [5] Poggiali G. et al. 2023a, Icarus, 394, 115449 [6] Poggiali G. et al. 2024, A&A 685, A14 [7] Pajola M. et al. 2025. A&A, (accepted) [8] Ruiz Lozano L. et al., (2024) EPSC2024-925 [9] Besse S. et al. 2018. PSS, 150, 131-140

How to cite: Poggiali, G., Alberini, A., Wargnier, A., Beccarelli, J., Ruiz Lozano, L., Yumoto, K., Besse, S., Pajola, M., Brucato, J. R., and Barucci, M. A.: The (Infrared) view of Phobos and Deimos, synergy between data from laboratory and remote sensing to understand the enigmatic nature of the Martian moons. , EPSC-DPS Joint Meeting 2025, Helsinki, Finland, 7–13 Sep 2025, EPSC-DPS2025-1606, https://doi.org/10.5194/epsc-dps2025-1606, 2025.

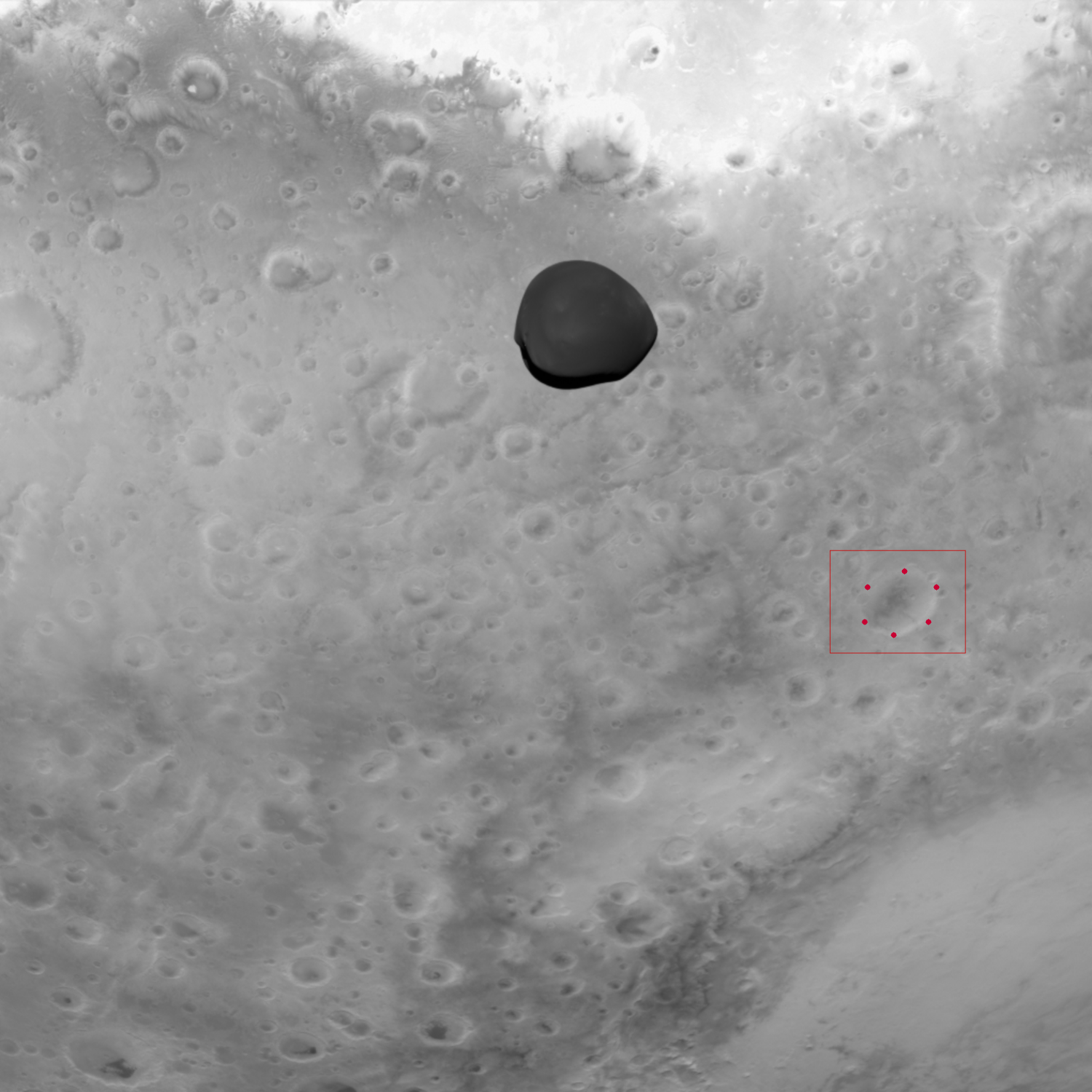

ESA’s Hera mission performed a Mars flyby on March 12, 2025, en route to the binary asteroid system Didymos–Dimorphos, which has been greatly influenced by NASA’s DART spacecraft impact (Michel et al. 2022). This flyby event presented a unique opportunity to observe extended light sources using Hera’s scientific instruments, which is crucial for their calibration. Additionally, the flyby offered a rare chance to observe the anti-Mars hemisphere of Deimos, as Mars orbiters, such as NASA’s Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter and ESA’s Mars Express, can only capture the sub-Mars hemisphere from their orbits.

Thanks to the great efforts of Hera’s flight dynamics team in optimizing the flyby timing to coincide with Deimos approaching Hera’s trajectory, along with precise spacecraft attitude control to track both Deimos and Mars in the field of views of cameras, Hera’s three complementary camera systems, Asteroid Framing Cameras (AFC), the HyperScout-H (HS-H) instrument, and JAXA’s Thermal Infrared Imager (TIRI), were able to observe both Mars and Deimos simultaneously.

The AFC captured over 230 images of Mars and more than 50 of Deimos. Although most Deimos images were small (≤ a few pixels across), they were taken at low solar phase angles (2–4°), which are valuable for constraining the phase function of Deimos’s anti-Mars side. The largest Deimos image (~140 pixels in diameter) was taken from a distance of 917 km. In total, the AFC acquired four images of this size range at phase angles between 13–17°, allowing for the identification of surface features.

The AFC images revealed a number of important geomorphologic features and albedo distribution on anti-Mars hemisphere. Notably, the anti-Mars hemisphere exhibits “streamers”, which are long, high albedo features similar to those seen on the sub-Mars hemisphere (P. Thomas et al. 1996, N. Thomas et al. 2011). The albedo contrast between the streamers and the surrounding terrain is comparable to that observed on the sub-Mars hemisphere, with variations reaching tens of percent. The albedo decreases monotonically from topographic highs to lows over several kilometers.

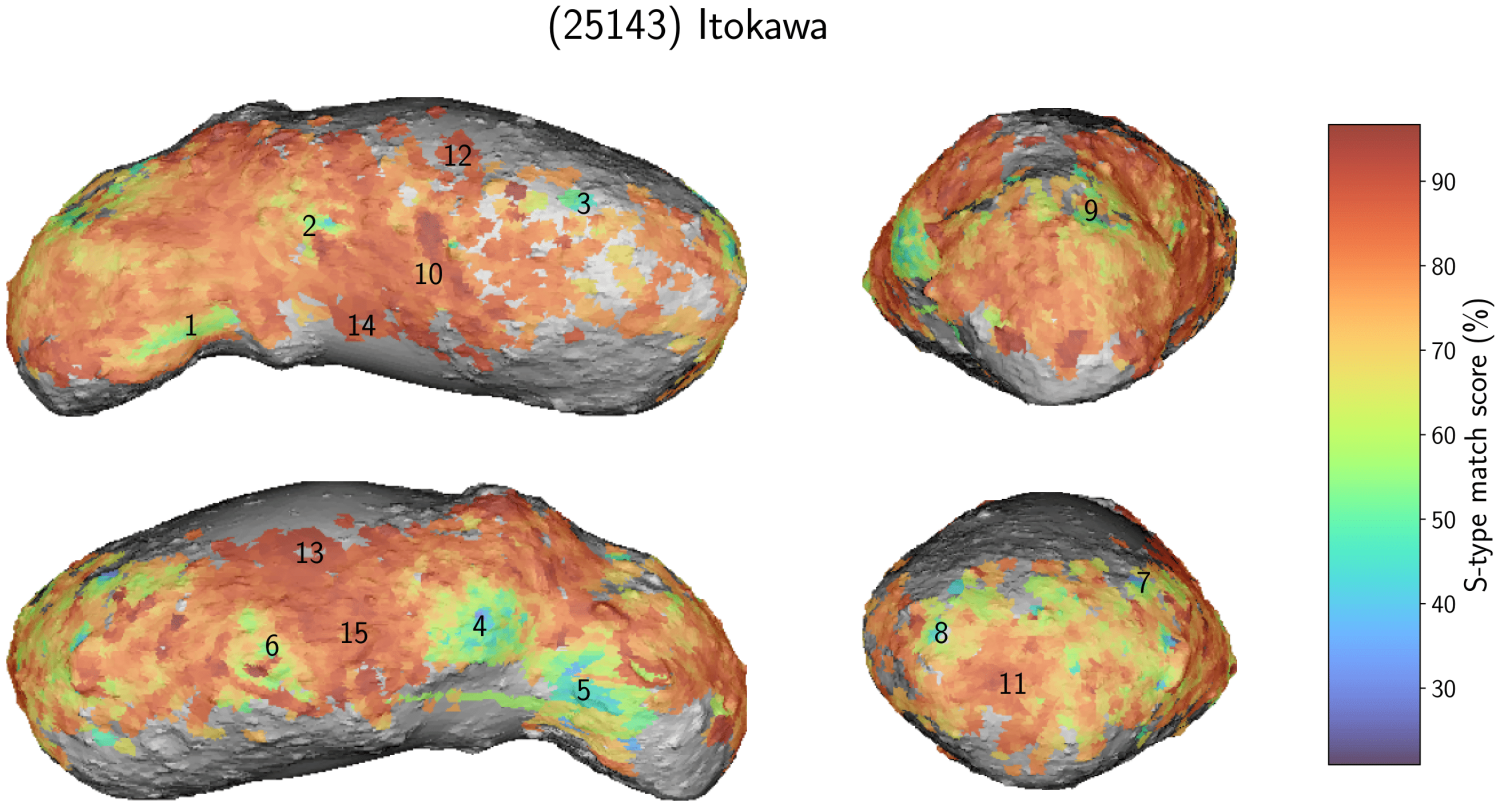

The albedo histogram of Deimos shows a highly asymmetric profile with a triangular shape: a sharp increase in frequency on the lower albedo side and a gradual decrease on the higher albedo side. This asymmetric histogram is similar to both the space weathering color index histogram (Koga et al. 2018) and the albedo histogram (Nakahara et al. 2023) observed on the S-type asteroid Itokawa. Although further analysis is needed to determine the exact cause, model calculations by Nakahara et al. (2023) suggest that the observation is consistent with a thin layer of regolith over a differently colored substrate. This could indicate space weathering, a mixture of two color components, or a combination of these processes. Regardless, the surface likely undergoes vertical mixing and diffusive mixing driven by the random motion of small regolith particles.

Understanding these surface characteristics will help constrain the nature of Deimos’ surface materials and optimize the observation plans of JAXA’s MMX mission, which will collect samples exclusively from Phobos. Consequently, proximity observations of Deimos will be crucial for comparing the similarities and differences between the two Martian moons (Kuramoto et al. 2022).

References:

Koga, S. et al. 2018. Spectral decomposition of asteroid Itokawa based on principal component analysis, Icarus, 299, 386-395.

Kuramoto, K., et al.., 2022. Martian moons exploration MMX: sample return mission to Phobos elucidating formation processes of habitable planets. Earth, Planets and Space 74, 12.

Michel, P., et al., 2022. The ESA Hera Mission: Detailed Characterization of the DART Impact Outcome and of the Binary Asteroid (65803) Didymos. Planet. Sci. J. 3, 160.

Nakahara, S. et al. 2023. Space weathering distribution and resurfacing on asteroids, JpGU, # MZZ40-02.

Thomas, N. et al. 2011. Spectral heterogeneity on Phobos and Deimos: HiRISE observations and comparisons to Mars Pathfinder results, Planet. Sp. Sci., 59, 1281-1292.

Thomas, P. et al. 1996. The Surface of Deimos: Contribution of Materials and Processes to Its Unique Appearance. Icarus, 123, 536-556.

How to cite: Sugita, S., Nakahara, S., Vincent, J.-B., Michel, P., Kovács, G., Ernst, C., Barnouin, O., Miyamoto, H., Kikuchi, H., and Kueppers, M.: Geomorphology and Albedo distribution on the Anti-Mars hemisphere of Deimos observed with Asteroid Framing Cameras (AFC) on the Hera Spacecraft, EPSC-DPS Joint Meeting 2025, Helsinki, Finland, 7–13 Sep 2025, EPSC-DPS2025-1786, https://doi.org/10.5194/epsc-dps2025-1786, 2025.

On March 12, 2025, the ESA Hera mission performed a flyby of Mars on the way to its target, the binary asteroid system Didymos–Dimorphos. This event provided a unique opportunity to acquire spectral data (within the 0.65–0.96 micron wavelength range) and high-resolution images of the far side of the Martian moon Deimos. The observations were conducted using the HyperScout-H (HS-H) instrument, the hyperspectral imager aboard the Hera spacecraft. Simultaneously, the mission's other two instruments, the Asteroid Framing Cameras (AFC) and the Thermal Infrared Imager (TIRI), also collected data on this small, irregularly shaped natural satellite of Mars.

Fig.1 A false-color image of Mars and Deimos was generated for public outreach using observations acquired by the HS-H instrument. In this visualization, the color channels were shifted: blue corresponds to 0.65 µm, while red represents 0.96 µm. Deimos appears black due to albedo differences compared to Mars surface.

The composition and geomorphology of Deimos have remained unclear despite multiple observations acquired over recent decades. Images obtained by various Mars missions reveal a low-albedo object (~0.08), while spectra acquired from both Earth-based observatories and space missions resemble those of C-, X-, and D-type asteroids (e.g., Fraeman et al. 2014; Takir et al. 2021). Furthermore, Deimos is tidally locked with Mars, orbiting at 6.92 Mars radii on an almost circular orbit (eccentricity 0.00024), inclined at 1.79° (with respect to equatorial plane). These properties are the key point for understanding the origin of this natural satellite. The leading hypotheses are: (1) asteroid capture, suggested by its spectral similarity to carbonaceous asteroids; and (2) formation from a giant impact, supported by the regularity of its orbit (e.g., Kuramoto 2024 and references there in).

The HS-H instrument acquired three images of Deimos. The highest-resolution image (Fig. 1) was obtained when the spacecraft was at a distance of 1024 km from the object, at a phase angle of approximately 15°. Two additional lower-resolution images were captured before, from distances of 8800 km and 6200 km and at phase angles of 2–3°.

The HS-H instrument is based on a 5 × 5 pattern of narrowband filters (defining a macropixel) placed and repeated over the CMOS detector pixels (referred to here as subpixels). This configuration enables the instrument to sample the spectrum of each surface patch between 0.65 and 0.96 microns across 25 spectral channels. As a result, HS-H simultaneously captures both spectral and imaging data. The highest-resolution image achieved a spatial resolution of approximately 134 meters per subpixel and primarily covers the far side of Deimos, an area that had never before been imaged in these wavelengths.

The raw images were processed using the HS-H instrument pipeline. Calibrations included bias and dark current subtraction, flat-field correction, and conversion to radiance factor (RADF). The result for the high-resolution image is shown in Fig. 2. Additionally, photometric corrections were applied to account for varying illumination conditions. Spectra corresponding to each macropixel were retrieved and analyzed in relation to the geomorphological properties of the surface. The spectra were compared with those reported by other instruments for Deimos inner side, such as the Colour and Stereo Surface Imaging System (CaSSIS) aboard the ExoMars Trace Gas Orbiter mission. These results will be presented and discussed with regard to their implications for the history of Deimos.

Fig. 2 Radiance factor for each subpixel (note that subpixels correspond to different wavelength channels arranged in a 5x5 pattern).

References

1. Fraeman A. A., et al. (2014), Icarus, 229, 196–205. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.icarus.2013.11.021

2. Takir D., et al. (2022), Icarus, 371, 114691. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.icarus.2021.114691

3. Kuramoto K. (2024), Annual Review of Earth and Planetary Sciences, 52(1), 495–519. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-earth-040522-110615

How to cite: Popescu, M., de León, J., Prodan, G. P., Küppers, M., Kovács, G., Nagy, B. V., Grieger, B., Escalante López, A., Sugita, S., Kohout, T., Korda, D., Tatsumi, E., Lazzarin, M., Farina, A., Poggiali, G., Bickel, V. T., Raducan, S. D., Licandro, J., Palomba, E., and Michel, P.: Spectral Characterization of the Far Side of Deimos Using the HyperScout-H Instrument Aboard the ESA Hera Spacecraft, EPSC-DPS Joint Meeting 2025, Helsinki, Finland, 7–13 Sep 2025, EPSC-DPS2025-1250, https://doi.org/10.5194/epsc-dps2025-1250, 2025.

Background:

Despite extensive study, the Mars system still possesses many mysteries, one of which is the formation of its moons Phobos and Deimos. Several mechanisms have been proposed but weather the moons formed as re-accreted ejecta [1] or as captured asteroids [2]) remains a significant problem. The key to solving this is currently thought to be held in the analysis of Phobosian ejecta, with numerical models having predicted it to contain, on average, 255 ppm of Martian material contaminant [3,4], transported to Phobos via impact processes.

Whilst numerical investigations have provided ranges for the level of detectable Martian material on Phobos [3,4,5,6], laboratory investigations are required into both the level of Martian material predicted on the surface of Phobos and its assumed detectability. Whilst some studies have previously found distinguishing features during spectral analysis of Phobosian surface analogues [7], an experimental investigation utilizing complex geological mixtures is lacking. This study therefore performed an experimental test of the assumed detectability of Martian material through the use of a geologically complex ‘Martian’ projectile impacting a geologically complex Phobos simulant target.

Method:

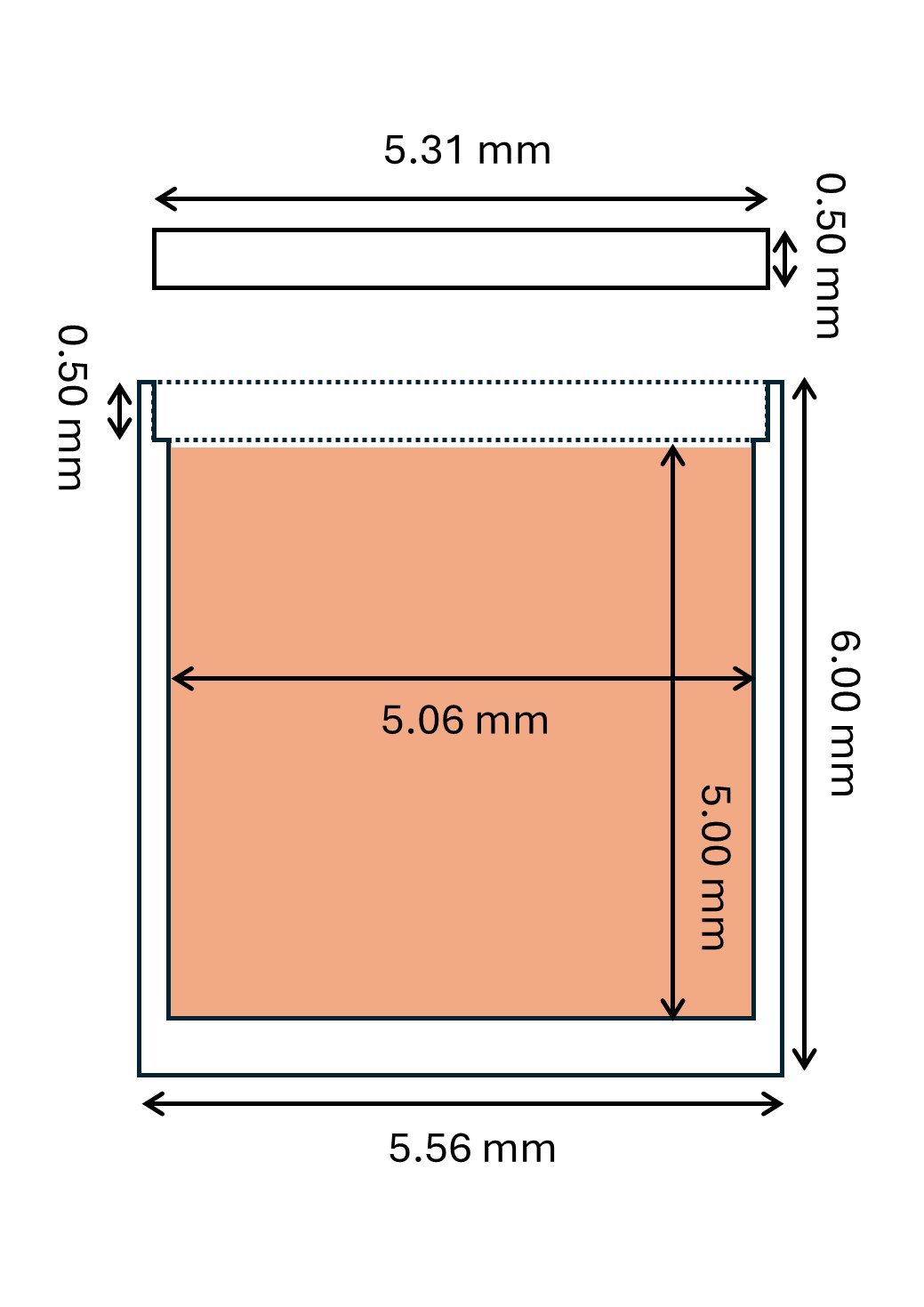

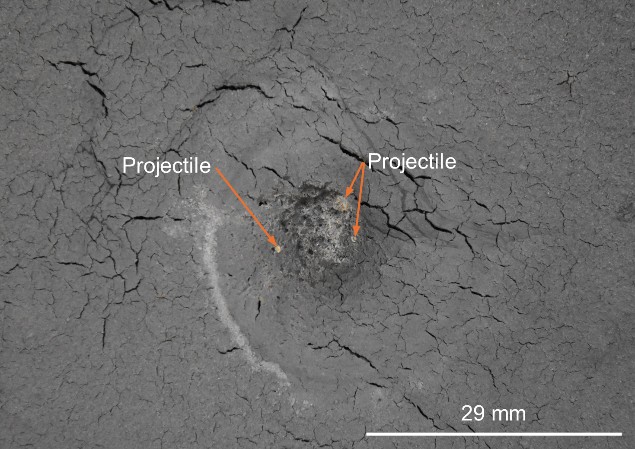

The work presented here assumes the case of a captured asteroid origin for Phobos. It presents the results from a shot series aiming to quantify the level of projectile material detectable during post-shot analysis. Six shots were carried out using the one and two stage light-gas gun at the University of Kent[10,11] over the speed range of 650 m/s to 1600 m/s covering the lower end of speeds predicted for material impacting the surface of Phobos [5]. The projectiles were designed to maximize the quantity of projectile material reaching the target and were formed of a custom designed 3D-printed UV-cured resin shell (Figure 1) containing an Eu-doped MGS-1 (Martian simulant) [8] mixture.

Figure 1: Schematic of the custom projectile shells for this investigation. The orange square in the schematic represents the projectile material.

This design of projectile allowed a geologically complex Martian simulant material to be used, with minimal preparation required, thus reducing chemical changes to the projectile. This was fired at cemented PCA-1 (Phobosian simulant) [9] target blocks (Figure 2) forming a geologically complex analogue of the Phobosian near-surface region. Targets were cubes with an average side length of 8.6 cm and depth of 5.8 cm. The average porosity was calculated to be 9.6% just is on the lower end of the current porosity range of 10-50% estimated for Phobos [1].

Figure 2: Pre-impact target within the Kent light-gas gun.

Post-shot analysis focused on two main questions: 1) can material from a Martian projectile be detected, and 2) can the level of detected material be quantified. For this, ejecta material was captured during each shot through the use of an ejecta capture cell. Not all of the ejecta from each shot was captured, but it is assumed that the material collected is representative of the entire population. Analysis was carried out on the ejecta sample and resultant impact crater separately, allowing the distribution of Martian contaminant material within the Phobosian regolith and the implantation of projectile material to be investigated separately.

Results and Discussion:

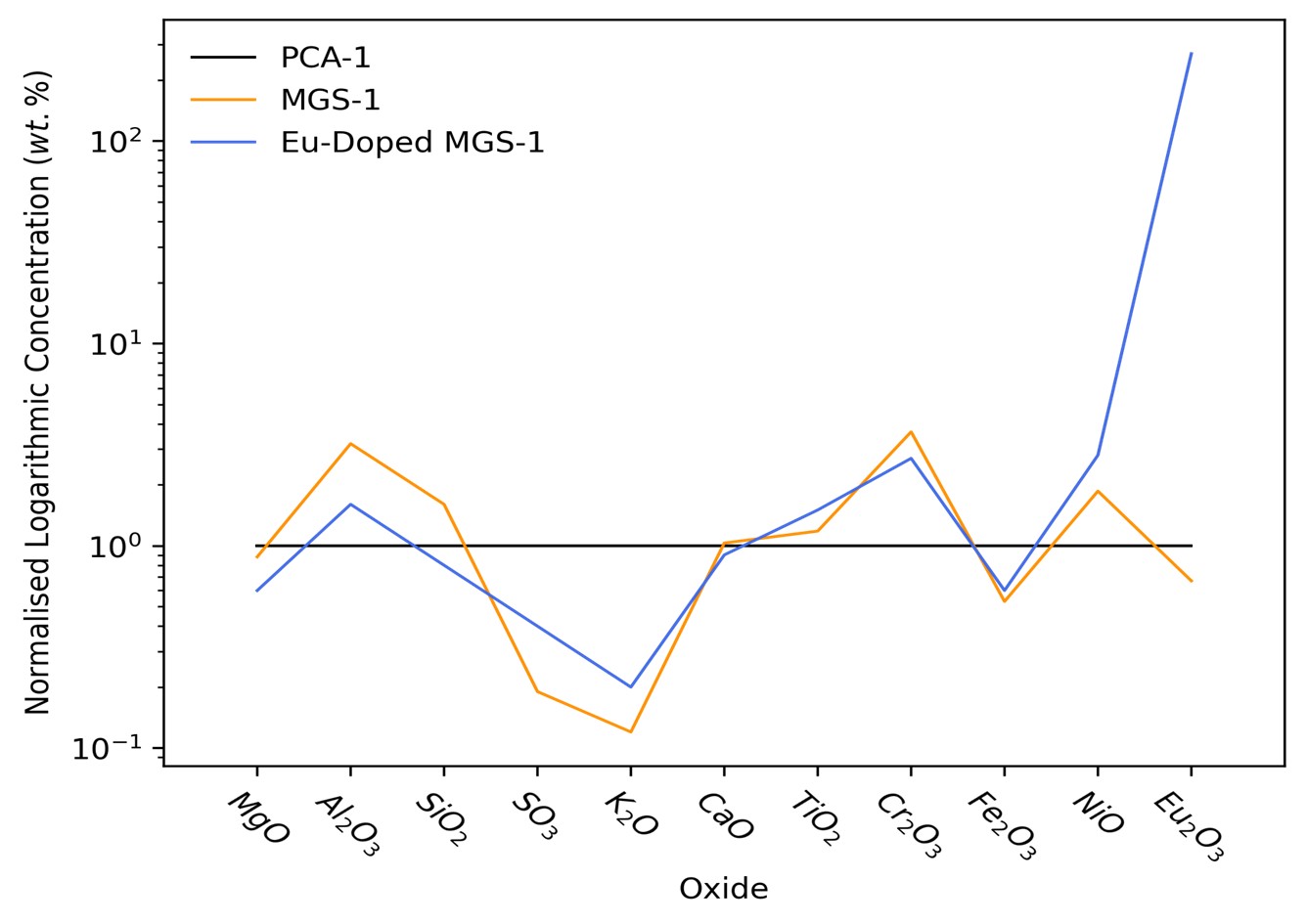

Figure 3: XRF results of pre-shot material. Values for each constituent are normalised to the values for PCA-1. The y-axis is presented as a logarithmic scale.

Collected ejecta samples were subjected to XRF, and XRD analysis, to both confirm and attempt to quantify the presence of projectile. To aid in the post-shot identification of projectile material, an elemental tracer (in the form of Eu(CH3CO2)3·XH2O) was included in the projectile. XRF analysis of the pre-impact material (Figure 3) shows clear differences between the PCA-1 and MGS-1 materials. Not only is the europium content of the projectile significantly higher than the background levels within the PCA-1 or MGS-1 simulants, characteristic variations between the two simulants (with differences being found between the measured K2O, Cr2O3, and NiO values) are also evident. Whilst the initial results show the clear presence of projectile material within the collected ejecta, further in-depth analysis is required to quantity its level. Initial observations of the impact features also shows the presence of projectile material (see Figure 4 and Figure 5).

Figure 4: Formed impact feature from shot 2 showing potential projectile material embedded within the crater.

Figure 5: Formed impact feature from shot 6. During the shot the projectile broke-up prior to impact. Potential projectile debris is highlighted.

Conclusions:

This study has demonstrated the ability to effectively fire a geologically complex ‘Martian’ projectile and subsequently detect this material within the impact target and ejecta. A full analysis of the targets and ejecta is now underway, with the aim of quantifying the level of successful transfer of impactor to the target. If successful this would provide an experimental test of previous numerical studies investigating the formation of Phobos.

References:

[1] R.I. Citron, et al., Icarus 252, 334 (2015).

[2] K.R. Ramsley, J.W. Head, Space Sci. Rev. 217, 86 (2021).

[3] K.R. Ramsley, J.W. Head, PSS 87, 115 (2013).

[4] P. Thomas, Icarus 131, 78 (1998).

[5] L. Chappaz, et al. Astrobiology 12, 936 (2013)

[6] R. Hyodo, et al., Sci. Rep. 9, 19833 (2019).

[7] G. Poggiali, et al., MNRAS 516, 465 (2022).

[8] K.M. Cannon, et al., Icarus 317, 470 (2019).

[9] Z.A. Landsman, et al., Advances in Space Research 67, 3308 (2021).

[10] M. Price, et al. International Journal of Impact Engineering 184, 104828 (2024)

[11] R. Hibbert, et al., Procedia Engineering 204, 208 (2017)

How to cite: Finch, E., Wozniakiewicz, P., Tandy, J., Burchell, M., Sefton-Nash, E., Avdellidou, C., Alesbrook, L., Koschny, D., and Spathis, V.: The mysterious Martian potato: An experimental investigation into the origin of Phobos, EPSC-DPS Joint Meeting 2025, Helsinki, Finland, 7–13 Sep 2025, EPSC-DPS2025-1484, https://doi.org/10.5194/epsc-dps2025-1484, 2025.

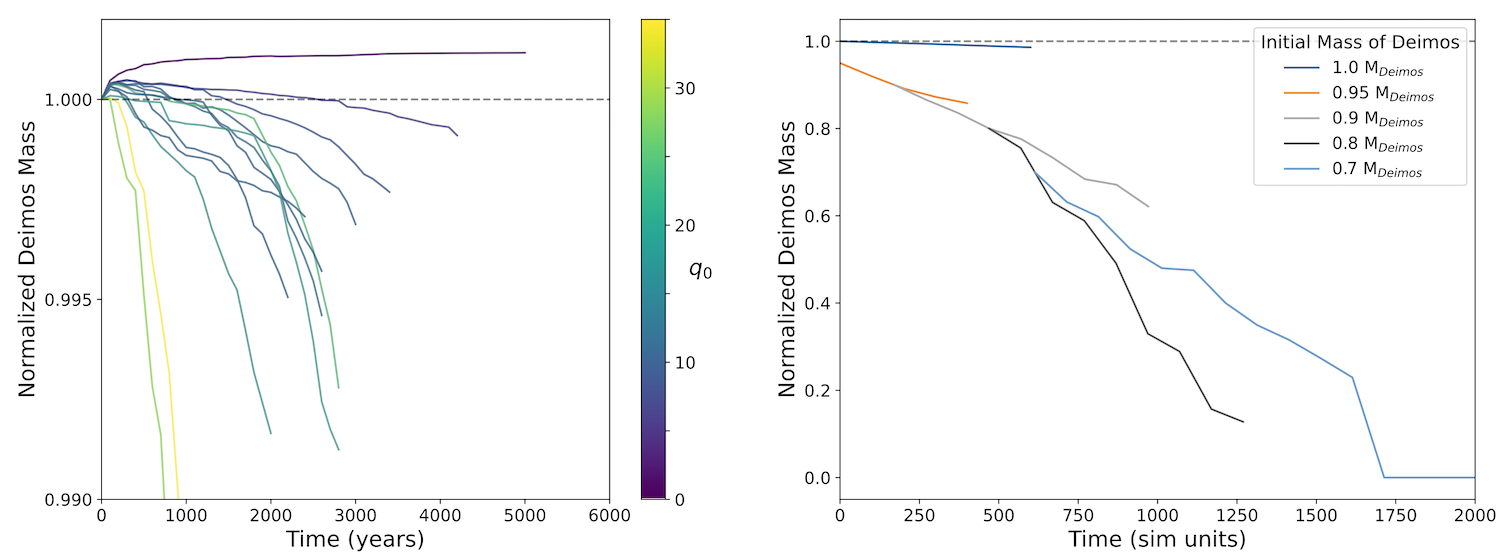

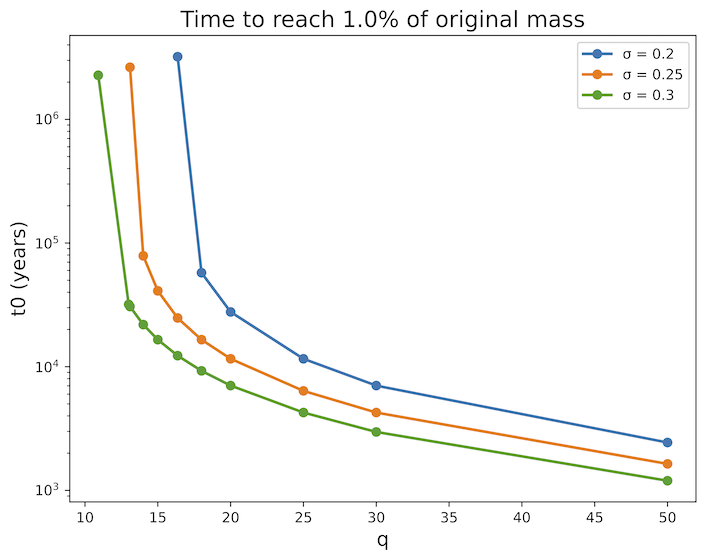

The origin of Phobos and Deimos remains uncertain. Over the years, several hypotheses have emerged: an impact between Mars and a planetesimal (Craddock (2011)), accretion from a debris disc ( Hesselbrock and Minton (2017)) or an asteroid capture (Hunten (1979), Rosenblatt (2011)). In 2021, Bagheri et al. (2021) proposed that both moons are fragments of a larger progenitor. Indeed, based on tidal forces, the authors have integrated backwards the orbital elements of the two satellites from their current positions, showing that the orbits of the two satellites may have crossed in the past. This leads them to conclude on a common origin. Hyodo et al. (2022)) then showed, in a simplified dynamic framework, that the post-fragmentation orbital elements resulting from this integration do not allow the newly-formed fragments to survive to the present day. In fact, a destructive collision between the two fragments seems difficult to avoid within 10,000 years of their formation. Thanks to a large number of N-body simulations, we have extended these results with a more complex physical model. We confirm the results of Hyodo et al. (2022) by taking into account more realistic physics: the survival of Phobos and Deimos until the present day in the formation scenario proposed by Bagheri et al. (2021) is quite limited.

How to cite: Dahoumane, R., Baillié, K., and Lainey, V.: Origin of Phobos and Deimos : Plausibility of a Fragmentation Scenario, EPSC-DPS Joint Meeting 2025, Helsinki, Finland, 7–13 Sep 2025, EPSC-DPS2025-309, https://doi.org/10.5194/epsc-dps2025-309, 2025.

Abstract:

The formation of Martian moons is one of the most enigmatic in the solar system. Long considered to be asteroids captured by Mars, a giant impact origin has recently been proposed, motivated by the exploration of Phobos by Mars Express (Paetzold et al., 2025). The objective of this study is to review recent formation scenarios proposed within the framework of this giant impact hypothesis.

1- The formation of two small moons from a giant impact

The asteroid capture scenario fails to explain the current near-circular and near-equatorial orbits of both moons (e.g., Rosenblatt, 2011). Alternatively, the giant impact scenario naturally explains the near-equatorial orbits by forming the two moons in an impact-induced debris disk (Craddock, 2011). Rosenblatt et al. (2016) and Canup and Salmon (2018) have shown that it is possible to accrete two small moons of the mass of Phobos and Deimos into this debris disk, on either side of the synchronous boundary. However, these small moons have elliptical orbits, and to match the near-circular orbit of Deimos requires a tidal dissipation rate of its interior that is not consistent with a rocky composition (Rosenblatt et al., 2016). Moreover, the composition of these small moons should be a mixture of materials from Mars and the impactor, which is not consistent with a purely primitive composition as suggested by remote sensing data from the surface of Phobos and Deimos.

2- The question of primitive composition

The giant impact is expected to eject fully molten rocky material into Martian orbit, composed of similar amounts of Martian and impact materials (Hyodo et al., 2017). This mixed material crystallizes primarily into olivine and pyroxene phases (Pignatale et al., 2018), which have not yet been identified in the remote sensing data (e.g., Wargnier et al., 2025). However, the ejected material is also expected to contain a small amount of volatile compounds (Pignatale et al., 2018), depending on the impactor composition, which could mimic the remote sensing signature of a primitive composition.

Kegerreis et al. (2024) also proposed the disruptive capture of an asteroid by the planet's tidal forces, leaving a cloud of primitive material in orbit. However, the authors did not study the accretion of two small moons from this cloud.

3- The question of the long-term orbital evolution of the Martian moons

Bagheri et al. (2021) proposed a large tidal dissipation rate in the Martian system, leading to a faster orbital evolution of Phobos and Deimos. They found that both moons could be at the same distance from Mars 1–3 Gyr ago, suggesting that they could originate from the breakup of a single progenitor. Nevertheless, the origin of such a progenitor is not explained in this model and the breakup process yields to the formation of several smaller fragments instead of just two (Hyodo et al., 2022). However, such a large tidal dissipation rate merits revisiting the orbital evolution of two small bodies formed around Mars or even captured by Mars.

4- Could Phobos have formed after Deimos?

Under the giant impact scenario, Hesselbrock & Minton (2017) propose that Phobos could have formed after Deimos. In this model, Phobos would result from multiple cycles of a ring-moon system. This model is consistent with the overall shape of Phobos (Hu et al., 2020) and the slightly inclined orbit of Deimos above the Martian equator, which could reflect gravitational interaction with a larger, former inner moon (Cuk et al., 2020). Nevertheless, a faint dust ring is expected to remain around Mars today (Madeira et al., 2023), which has not been observed so far. Furthermore, the retention age of Phobos surface craters is as old as 4.3 Gyr (Schmedemann et al., 2014), which is inconsistent with a younger Phobos according to this model.

5- How could the Martian Moon eXplorer data help discriminate between these formation scenarios?

The sample collected at Phobos’ surface will provide determined its composition (Usui et al., 2020). However, this surface could be contaminated by ejecta from the Martian surface, making it difficult to distinguish between the impact debris disk model and the asteroid disruptive capture model. One solution to resolve this ambiguity is to measure the magnetic properties of the sample. Indeed, if the material forming Phobos is condensed in Martian orbit, it should record the strong magnetic dipole field of the early Mars (Rosenblatt et al., 2024). If the Circum-Martian Dust Monitor measured a low-dense ring of material around Mars (Kobayashi et al., 2019), this would support the ring-moon cycle model. The geodesy experiment will allow for better constraint on the internal structure of Phobos (Yamamoto et al., 2024), thus the modeling of its tidal dissipation properties. The MMx data will open the way to exciting research aimed at answering the following question: Is Mars capable of maintaining small accreted moons in orbit throughout its history, or even capturing asteroids, to ultimately form the current Martian lunar system?

References:

Bagheri A. et al. (2021) Nat. Astron. 5:539; Canup R. & Salmon J. (2018) Sci. Adv. 4 :4; Craddock, R.A. (2011) Icarus, 211:1150; Cuk M. et al. (2020) ApJ. Lett. 896:id.L28; Hesselbrock A.J. & Minton D.A. (2017) Nat. Geosci. 10:266; Hu X. et al. (2020) GRL 47; Hyodo R. et al. (2017) ApJ 845:125; Hyodo R. et al. (2022) 3:204; Kegerreis J.A. et al. (2024) arXiv :2407.15936v1; Kobayashi et al. (2019) EPSC-DPS 2019-1669; Madeira G. et al. (2023) Astron. J. 165:4; Paetzold M. et al. (2025) Space Sci. Rev., 221:41; Pignatale F.C. et al. (2018) ApJ 853:118; Rosenblatt P. (2011) A&A Rev. 19-44; Rosenblatt et al. (2016) Nat. Geosci. 9:581; Rosenblatt P. et al. (2024) COSPAR 0032-24; Schmedemann et al. (2014) Planet. Space Sci. 102:152; Usui T. et al. (2020) Space Sci. Rev. 216:49; Wargnier A. et al. (2025) A&A 694:A304; Witasse O. et al., (2014) Planet. Space Sci., 102:18-34; Yamamoto K. (2024) Earth, Planet. Spac. 76:id.86

How to cite: Rosenblatt, P.: A giant impact scenario to form the Martian moons?, EPSC-DPS Joint Meeting 2025, Helsinki, Finland, 7–13 Sep 2025, EPSC-DPS2025-329, https://doi.org/10.5194/epsc-dps2025-329, 2025.

Please decide on your access

Please use the buttons below to download the supplementary material or to visit the external website where the presentation is linked. Regarding the external link, please note that Copernicus Meetings cannot accept any liability for the content and the website you will visit.

Forward to presentation link

You are going to open an external link to the presentation as indicated by the authors. Copernicus Meetings cannot accept any liability for the content and the website you will visit.

We are sorry, but presentations are only available for users who registered for the conference. Thank you.

The two small satellites of Mars, Phobos and Deimos, have low-eccentricity obits close to the plane of the Martian equator, implying their in-situ formation (Burns, 1992). The most common proposed hypothesis for their origin is that the moons formed from debris ejected by a giant impact onto early Mars (Craddock, 2011; Rosenblatt and Charnoz, 2012; Citron et al., 2015; Rosenblatt et al., 2016; Hesselbrock and Minton, 2017; Hyodo et al., 2017; Canup and Salmon, 2018). Much is unknown about how the initial giant impact gave rise to the current moons, as Phobos (and any other more massive moons present in the past) likely experienced large-scale tidal evolution over the age of the Solar System. As Mars is a relatively slow rotator, all moons orbiting interior to the synchronous orbit at about 6 Mars radii (RM) orbit faster than Mars spins and tidally migrate inward (Deimos is just outside synchronous orbit, at 6.92 RM).

Hesselbrock and Minton (2017) (HM17) have proposed that Phobos is not primordial, but a product of ring-moon cycles over the age of the Solar System. According to HM17, successive generations of Martian moons formed from successive generations of rings. After forming at the outer edge of the rings (near the Fluid Roche Limit at 3.2 RM ), the moons migrate outward through interactions with the ring until the ring dissipates. When the ring torques become too weak to counter Martian tides, the moons migrate inward, until the Martian tides disrupt them at the rigid Roche Limit (at 1.6 RM ), forming the next generation of the Martian ring (cf. Black and Mittal, 2015). Each generation of moons is several times less massive than the previous, as inward tidal evolution drains angular momentum from the system, and the rest of the mass is accreted onto Mars.

One of the conclusions of HM17 was that, over several Gyr, mass many times larger than that of Phobos was deposited over the equatorial regions of Mars due to ring infall. So far, there have not been any claims of geological or geochemical features on Mars that would be related to this mass infall. Here we revisit the dynamics of the putative past ring of Mars and show that its evolution would have been complex and largely shaped by solar resonances.

During its past and future evolution Phobos crosses several solar semi-secular resonances (SSRs), in which a moon’s precession period is a multiple or a simple fraction of Mars’s heliocentric orbital period. Unlike mean-motion resonances in which capture can happen only during convergent evolution (Murray and Dermott, 1999), capture into eccentricity and inclination-type solar SSRs requires different directions of migration. When the planet’s oblateness is the dominant source of perturbation, a satellite’s orbit precesses faster as eccentricity grows (Danby, 1992), making capture into constant-precession-rate resonances possible during outward migration (e.g. evection resonance; Touma and Wisdom, 1998; Cuk and Stewart, 2012). However, inclined orbits precess more slowly than planar (Danby, 1992), making inward migration a requirement for capture into an inclination-type SSR. This has previously been confirmed numerically for the 2:3 SSR (Touma and Wisdom, 1998) and 2:1 SSR (Yokoyama, 2002; Yokoyama et al., 2005). The 2:1 SSR is of particular interest for modeling the future dynamics of inward migrating moons and rings resulting from their disruption.

Figure 1: The capture of a ring particle (or a moon) into the 2:1 solar semi-secular resonance, at about 2.15 RM. As the particle's orbit is shrinking, it is moving right to left in the plot. At this distance the apsidal and nodal precession periods are 0.5 martian years. The particle's orbit is captured into the resonance and the inclination keeps increasing as the particle drifts closer to Mars. This resonance was first described by Yokoyama et al. (2005), so we refer to it as the Yokoyama resonance.