Multiple terms: term1 term2

red apples

returns results with all terms like:

Fructose levels in red and green apples

Precise match in quotes: "term1 term2"

"red apples"

returns results matching exactly like:

Anthocyanin biosynthesis in red apples

Exclude a term with -: term1 -term2

apples -red

returns results containing apples but not red:

Malic acid in green apples

hits for "" in

Network problems

Server timeout

Invalid search term

Too many requests

Empty search term

TP6

modeling that help to understand processes at past, present or future landing sites.

Session assets

1. Introduction

The Mars Environmental Dynamics Analyzer (MEDA) instrument onboard the Mars 2020 Perseverance rover [1] has been measuring the environmental conditions at Jezero Crater for over 1450 sols since landing, covering from Ls ~ 5° in MY 36 to Ls ~ 70° in MY 38, and it continues to operate. Here we detail MEDA’s evolving measurement strategy under changing resource constraints, describe sensor performance, and present processed data through sol 1450.

2. MEDA Measurement Strategy

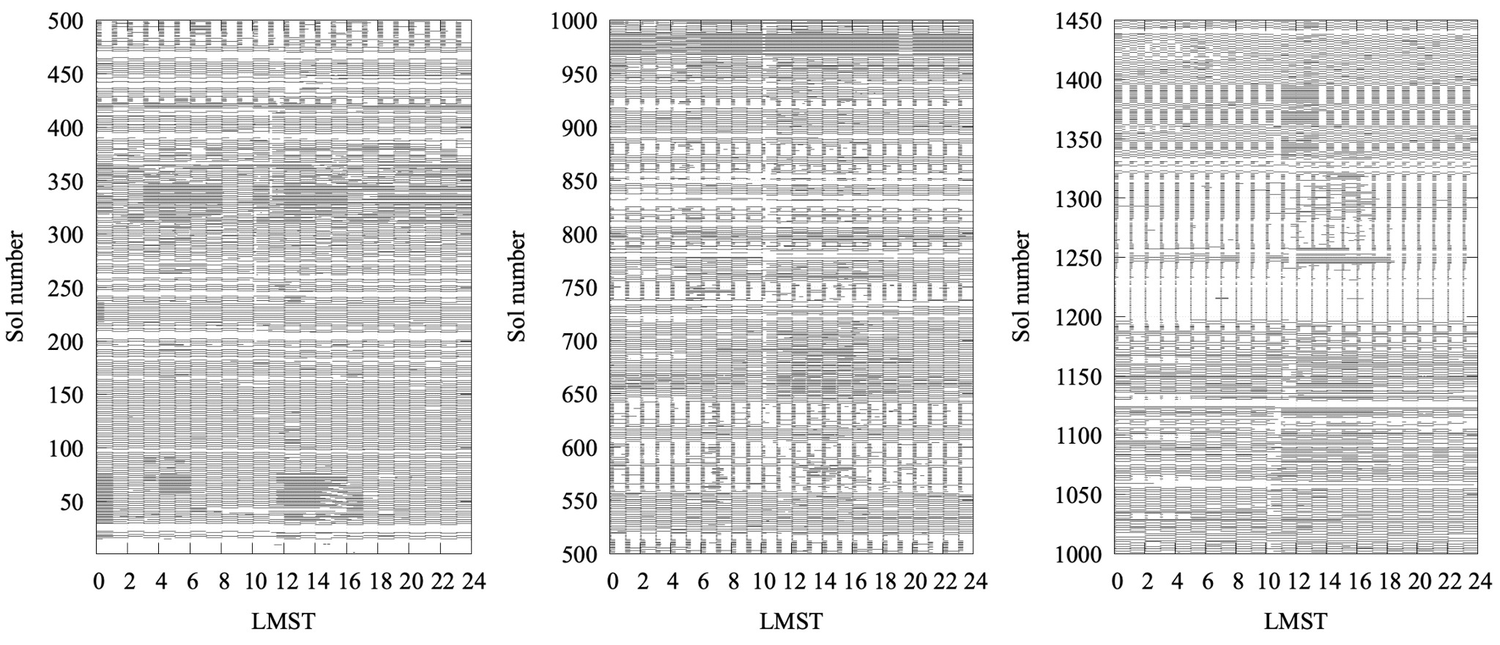

MEDA’s daily measurement cadence has varied throughout the mission in response to available resources (Fig. 1). Until sol 1116, MEDA followed a nominal cadence of 1h-and-5' blocks starting at odd hours on odd sols, and even hours on even sols, with 3 to 4 SkyCam images per sol. Additional blocks were added when resources allowed. During each block, MEDA sensors operated at 1 Hz, although some sensors occasionally recorded at 2 Hz.

Figure 1. Temporal coverage through sol 1450.

A reduced cadence was implemented from sol 1197 to 1319, consisting of 5’ or 10' blocks at the start of each hour, 1 Hz sampling, and 2 SkyCam images per sol. Beginning on sol 1320, and due to Wind Sensor (WS) degradation from sand abrasion, a new nominal cadence was adopted with 30’ blocks covering hh:00-hh:30 on even sols, and hh:30-hh:00 on odd sols, two additional 30’ floating blocks to support science activities, and 2 SkyCam images. Under this cadence, the WS is only active for 15’ every 2h for a total of 4h per sol, while the Atmospheric Temperature Sensor (ATS), Thermal Infrared Sensor (TIRS), Pressure Sensor (PS), Humidity Sensor (HS), and Radiation and Dust Sensor (RDS) operate 13h per sol.

3. Sensor Performance

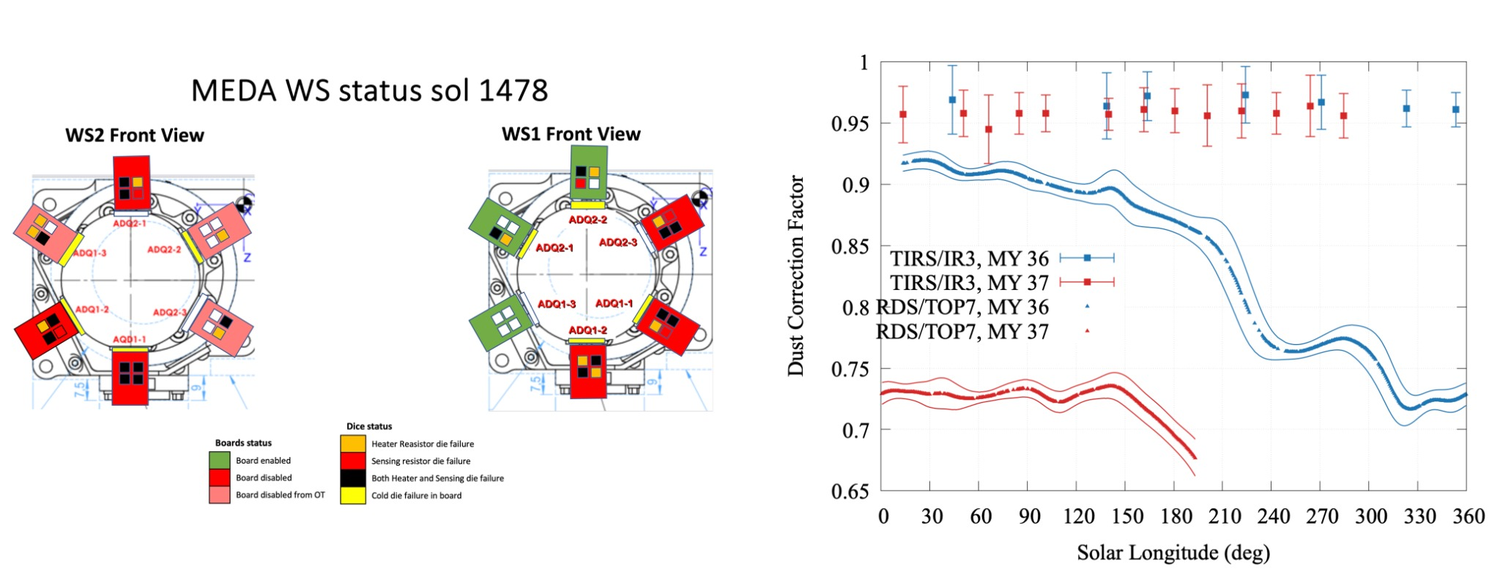

All MEDA sensors are operating nominally except for the WS, which has suffered progressive damage from saltating sand and dust grains (Fig. 2, left). The first major damage occurred during a dust devil encounter on sol 313, limiting WS measurements of the highest confidence to the first 313 sols. The WS was reactivated on sol 345 with reduced capability, and further failures have since occurred. Optimized methods are being developed to interpret wind conditions from the remaining sensor outputs, with plans to release these data soon.

Figure 2. (Left) WS status as of sol 1478, showing the damage to the boards and dice, color-coded by severity. (Right) DCF as a function of Ls for the upward-looking TIRS/IR3 (0.3–3 µm) and RDS/TOP7 (0.19–1.2 µm) channels during MY 36 and 37.

Figure 2. (Left) WS status as of sol 1478, showing the damage to the boards and dice, color-coded by severity. (Right) DCF as a function of Ls for the upward-looking TIRS/IR3 (0.3–3 µm) and RDS/TOP7 (0.19–1.2 µm) channels during MY 36 and 37.

While TIRS and RDS continue to operate nominally, dust accumulation on them requires corrections to their readings. The Dust Correction Factor (Fig. 2, right) is used to quantify the fraction of the incoming surface radiation that reaches the RDS/TOP7 and TIRS/IR3, respectively [2,3]. While TIRS measurements available in NASA’s PDS are corrected for this effect, RDS measurements are not.

4. Processed MEDA Data through Sol 1450

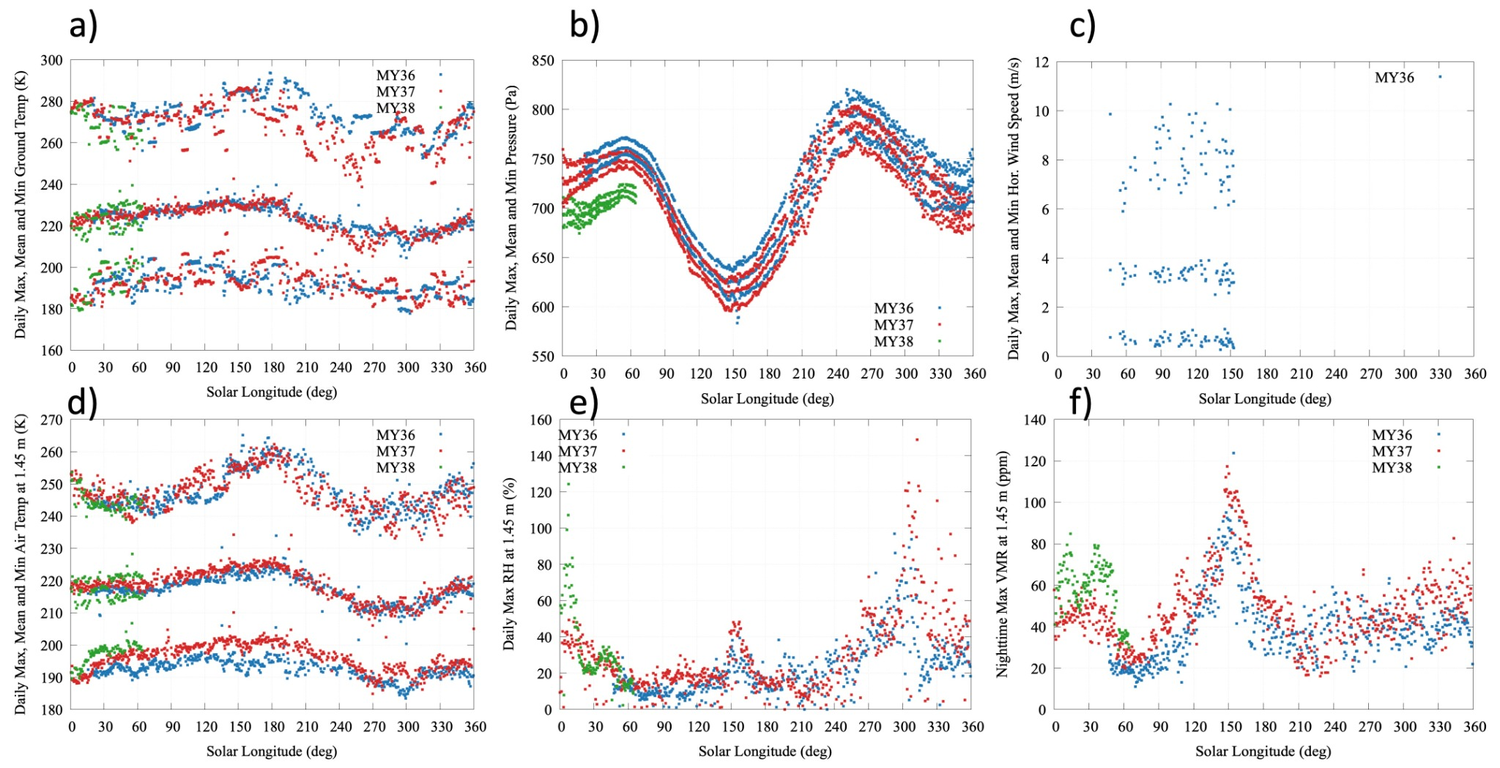

Fig. 3 shows the seasonal and interannual evolution of the environmental quantities measured by MEDA. Data from TIRS, PS, WS, and ATS were calculated as averages over the first 5’ of each hour and half-hour. For the HS, only measurements taken during the first few seconds after the HS was activated (following at least ~5 minutes of inactivity) were considered to avoid heating effects [4]. Water vapor volume mixing ratio was calculated as VMR = RH × es(T)/P, where esis the saturation vapor pressure over ice. Due to low daytime RH, MEDA-derived VMR values are restricted to nighttime.

Figure 3. Environmental conditions through sol 1450. Daily maximum, mean, and minimum ground temperature (a); atmospheric pressure (b); horizontal wind speed (c); air temperature (d), where only ATS1, ATS2, and ATS3 have been considered; daily maximum relative humidity (e); and nighttime maximum water vapor VMR (f).

Figure 3. Environmental conditions through sol 1450. Daily maximum, mean, and minimum ground temperature (a); atmospheric pressure (b); horizontal wind speed (c); air temperature (d), where only ATS1, ATS2, and ATS3 have been considered; daily maximum relative humidity (e); and nighttime maximum water vapor VMR (f).

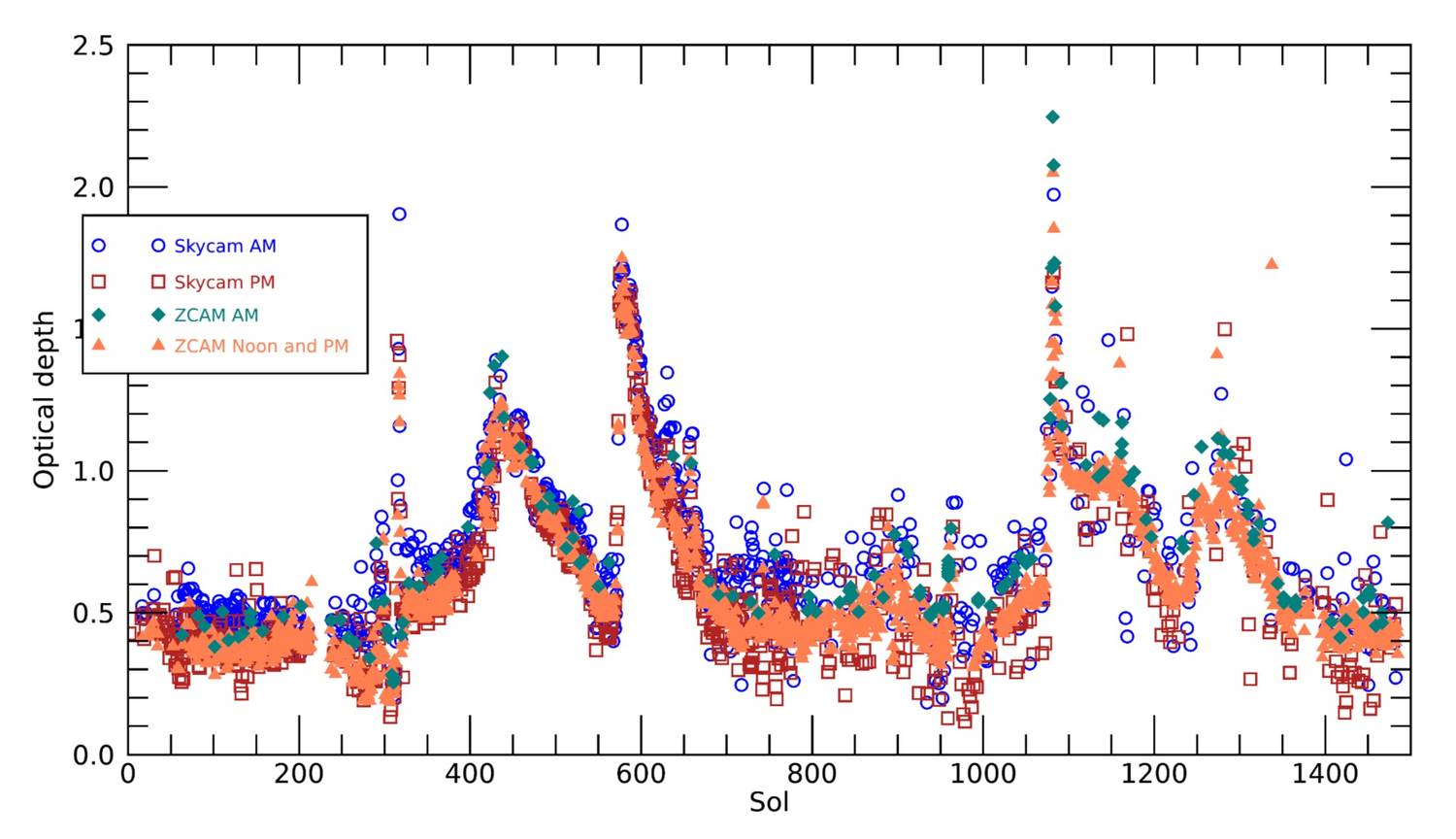

Fig. 4 shows the aerosol opacity retrieved from SkyCam through sol 1450. For comparison, retrievals from the ZCAM instrument [5] are also shown. After approximately sol 700, sand and dust particles accumulated on the SkyCam may have introduced outliers.

Figure 4. Aerosol opacity (dust + water ice) retrieved from SkyCam (0.691 µm) and ZCAM (0.88 µm), color-coded by acquisition time.

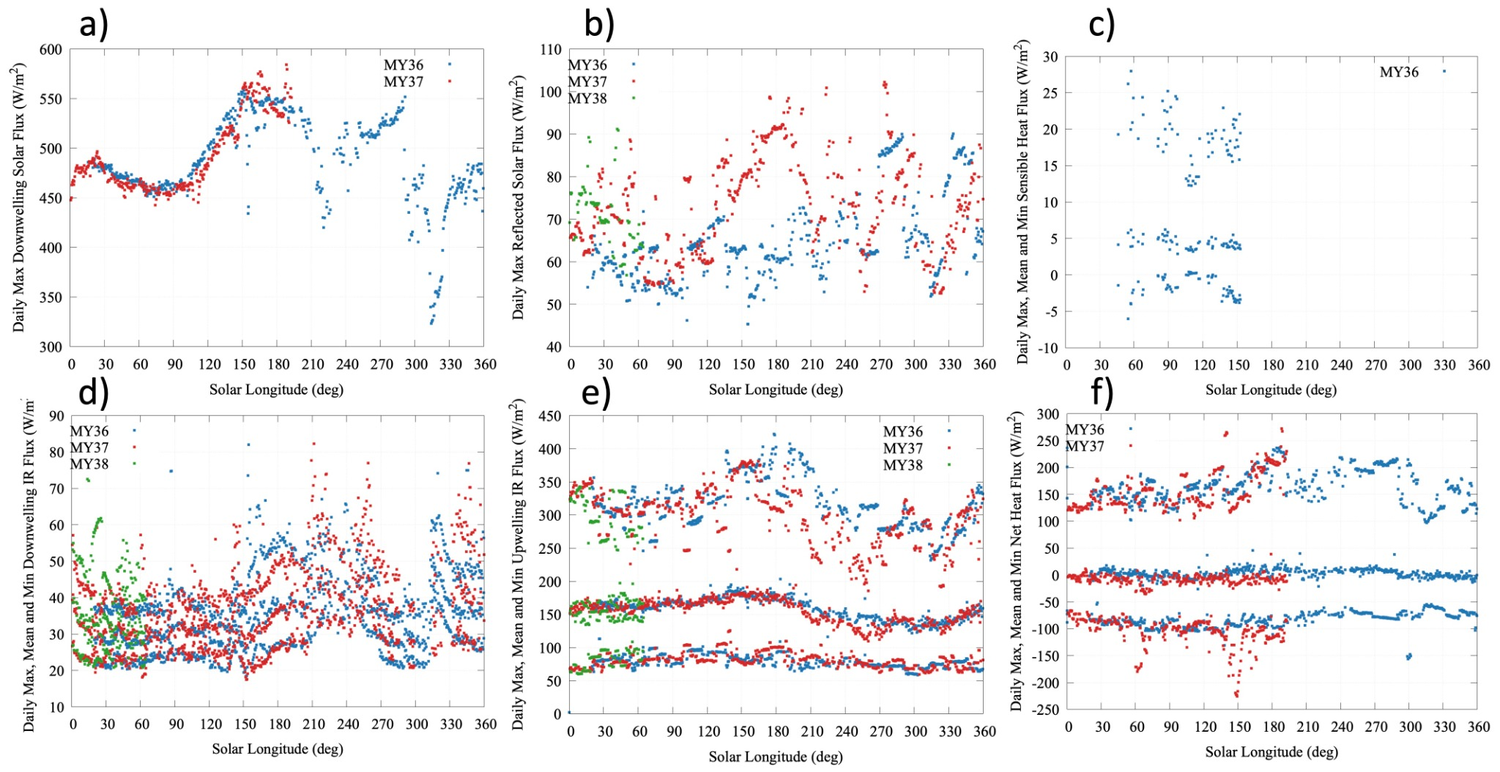

Fig. 5 shows the seasonal and interannual evolution of each surface energy budget term. Downwelling and reflected solar fluxes have been extended to the full solar range (0.19–5 mm) as described in [6]. The limited coverage of the downwelling solar flux and the sensible heat flux is due to the availability of the DCF, which has only been calculated through sol 1051 (Fig. 2, right), and to the availability of WS data. Similarly, the net heat flux into the ground has been computed only through sol 1051, based on the availability of dust-corrected downwelling solar fluxes. Daily minimum net heat flux values in MY 37 centered around Ls ~50° and 150° are caused by shadows affecting the RDS, which result in artificially low net heat flux values.

Figure 5. Surface energy budget at Jezero Crater through sol 1450. (a) Daily maximum downwelling solar flux (0.19–5 µm). (b) Daily maximum reflected solar flux (0.19–5 µm). (c) Daily maximum, mean, and minimum sensible heat flux. (d) Daily maximum, mean, and minimum downwelling longwave flux (5–80 µm). (e) Daily maximum, mean, and minimum upwelling longwave flux emitted by the surface (5–80 µm). (f) Daily maximum, mean, and minimum net heat flux.

Acknowledgments

This work has been funded by the Spanish MEC, through projects No. ESP2014-54256-C4-1-R and AYA2015- 65041-P; MCIU, No. ESP2016-79612-C3-1-R, ESP2016-80320-C2-1-R, RTI2018-098728-B-C31, RTI2018-099825-B-C31, MDM-2017-0737 and PID2021-126719OB-C41; INTA and CDTI.

References

[1] Rodríguez-Manfredi, J. A., et al. (2021). Space Sci. Rev., 217(3), 1–86. [2] Sebastián, E., et al. (2025), Acta Astronaut., 226, 791–802. [3] Vicente‐Retortillo, A., et al. (2024). Geophys. Res. Lett., 51, e2023GL107975. [4] Polkko, J., et al. (2023). J. Geophys. Res. Planets 128, e2022JE007447. [5] Bell, J. F., et al. (2021). Space Sci. Rev., 217, 24. [6] Martínez, G. M., et al. (2023). J. Geophys. Res. Planets, 128, e2022JE007537.

How to cite: Martinez, G., Manfredi, J. A., de la Torre-Juarez, M., Apéstigue, V., Gomez, F., Genzer, M., Harri, A.-M., Hieta, M., Hueso, R., Lemmon, M., McConnochie, T., Munguira, A., Newman, C., Pla-Garcia, J., Polkko, J., Sanchez-Lavega, A., Sebastian, E., Tamppari, L., Toledo, D., and Vicente-Retortillo, A.: MEDA on Mars 2020: Environmental Data and Sensor Insights through Sol 1450, EPSC-DPS Joint Meeting 2025, Helsinki, Finland, 7–13 Sep 2025, EPSC-DPS2025-1461, https://doi.org/10.5194/epsc-dps2025-1461, 2025.

Understanding Martian meteorology at the surface is essential for future robotic and human exploration. The Mars 2020 Perseverance rover has provided an unprecedented opportunity to analyze the atmospheric environment of Jezero crater through its onboard weather station, MEDA (Mars Environmental Dynamics Analyzer, [1]). Prior to landing, [2] and [3] presented a set of model-based predictions for atmospheric behavior at the landing site. The purpose was to guide mission operations and serve as a baseline for post-landing model validation using real data. This study represents the fulfillment of that goal, providing a detailed comparison between in situ observations and mesoscale model predictions on Mars.

We compare MEDA observations of pressure, air and ground temperature, and horizontal wind speed and direction with MRAMS simulations at high spatial and temporal resolution. Unlike previous efforts that focused on four seasonal snapshots (solstices and equinoxes), our study incorporates MRAMS simulations of full diurnal cycles every 30° of solar longitudes (Ls) across two full Martian years. This represents the highest frequency of mesoscale modeling ever conducted at high resolution (330 m horizontal grid spacing) on Mars, offering unprecedented insight into both seasonal and interannual variability.

A diurnal structure variation of the pressure throughout the year is shown both in modeling and observations. The diurnal pressure amplitude is generally well matched in the model. Pressure normalization techniques were applied to correct for model biases, leading to improved alignment with MEDA values.

The general shape of the diurnal cycle of surface temperature is similar between the two datasets. MRAMS surface properties are interpolated from TES-derived thermal inertia datasets, which lack the spatial resolution necessary to fully capture Jezero’s known heterogeneity. This limitation likely contributes to inaccuracies in the modeled diurnal temperature amplitude.

There is a good match in wind directions between MRAMS and MEDA in most cases, but MRAMS wind speeds are generally higher than those observed with MEDA, especially between 01:00 and dawn. Those wind speed differences could be so strong because the downslope winds penetrate a little bit too far into the crater for that time of sol when compared with other modeling predictions. It is also noticeable that the wind speeds are systematically very low after sunset both in MRAMS and MEDA, following the collapse of daytime convection, but then at 20:00 the wind speeds start to increase again both in modeling and observations.

This study extends the investigation of nighttime turbulence over two Martian years presented in [4], which showed that turbulence increases as the rover approaches the western rim of Jezero crater. This enhancement may be caused by wind shear originating from the passage of an atmospheric bore wave associated with downslope winds descending from the crater’s western rim.

Overall, the agreement between MEDA and MRAMS supports the use of high-resolution mesoscale modeling as a predictive and diagnostic tool for Mars surface meteorology, and justifies the use of the model results to investigate the broader meteorological environment of the Jezero crater region. These findings support ongoing efforts to refine mesoscale modeling approaches for Mars and highlight the value of MEDA in validating model outputs at unprecedented temporal resolution. The enhanced temporal frequency of simulations—combined with careful pressure normalization and detailed analysis—provides a robust validation framework. This work also highlights the need for improved surface property characterization to enhance model fidelity, particularly for thermal processes. These results are not only valuable for reconstructing the meteorological environment of Jezero crater during the Mars 2020 mission, but also for informing future landing site selection, engineering planning, and science operations in similar terrain.

References:

[1] Rodriguez-Manfredi, J. A., De la Torre Juárez, M., Alonso, A., Apéstigue, V., Arruego, I., Atienza, T., ... & MEDA team. (2021). The Mars Environmental Dynamics Analyzer, MEDA. A suite of environmental sensors for the Mars 2020 mission. Space science reviews, 217, 1-86.

[2] Pla-García, J., Rafkin, S. C., Martinez, G. M., Vicente-Retortillo, Á., Newman, C. E., Savijärvi, H., ... & Harri, A. M. (2020). Meteorological predictions for Mars 2020 Perseverance Rover landing site at Jezero crater. Space science reviews, 216(8), 148.

[3] Newman, C. E., de la Torre Juárez, M., Pla-García, J., Wilson, R. J., Lewis, S. R., Neary, L., ... & Rodriguez-Manfredi, J. A. (2021). Multi-model meteorological and aeolian predictions for Mars 2020 and the Jezero crater region. Space Science Reviews, 217, 1-68.

[4] Pla‐García, J., Munguira, A., Rafkin, S., Newman, C., Bertrand, T., Martínez, G., ... & Rodríguez‐Manfredi, J. A. (2023). Nocturnal turbulence at Jezero crater as determined from MEDA measurements and modeling. Journal of Geophysical Research: Planets, 128(8), e2022JE007607

How to cite: Pla-Garcia, J., Newman, C., and Rodríguez-Manfredi, J. A.: The meteo of Jezero crater as determined from MEDA observations and modeling, EPSC-DPS Joint Meeting 2025, Helsinki, Finland, 7–13 Sep 2025, EPSC-DPS2025-1003, https://doi.org/10.5194/epsc-dps2025-1003, 2025.

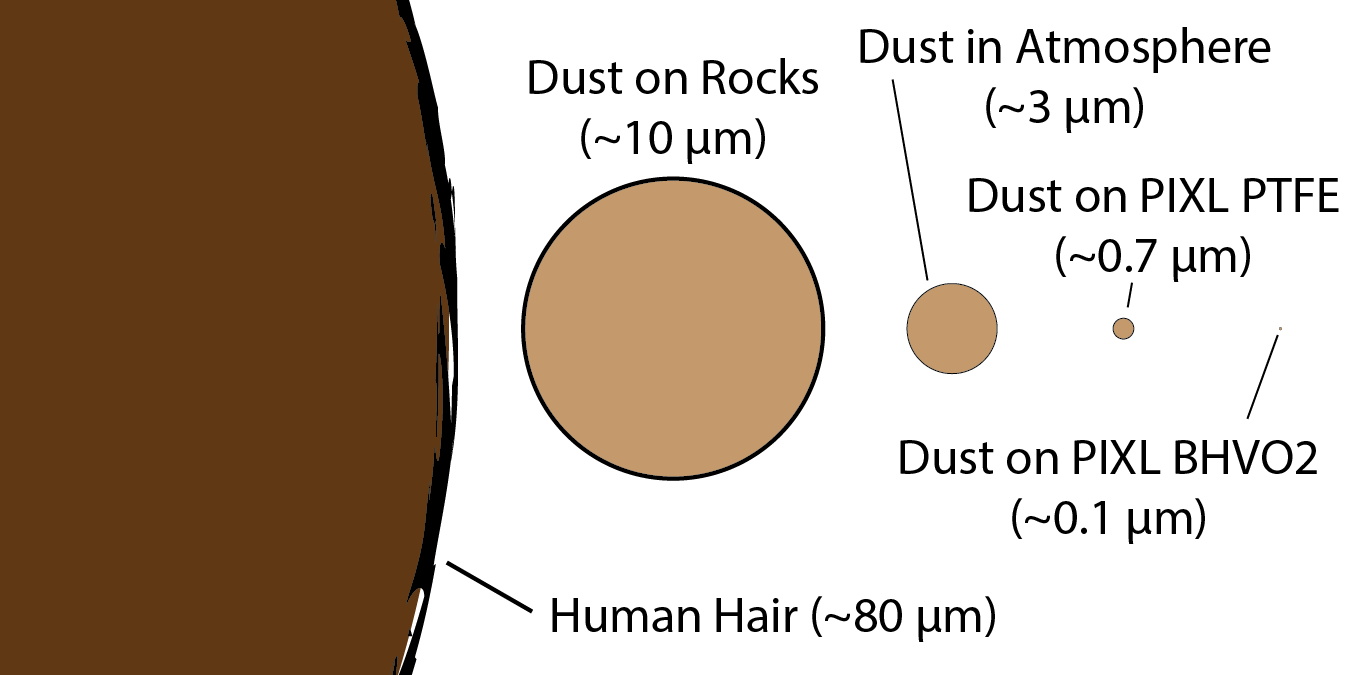

Aerosols on Mars are a primary element for studying the interaction between the solar radiation and the atmosphere and surface. Depending on properties such as aerosol number density, particle radius, or refractive index, the aerosols can provide positive or negative radiative feedbacks on the atmospheric dynamics. Previous studies have revealed large temporal and spatial variability in the aerosol optical properties, emphasizing the need for continuous monitoring throughout the day and at multiple locations. To address these measurements, the Radiation and Dust Sensor (RDS) [1] was included as part of the Mars Environmental Dynamics Analyzer (MEDA) [2] payload onboard the Perseverance rover of the Mars 2020 mission. The RDS instrument is composed of two sets of eight photodiodes (RDS-DP) and a sky-pointed camera (RDS-SkyCam). One set, oriented toward the zenith, captures radiation from 190 to 1200 nm, while the other, inclined 20° above the horizon at 45° azimuthal intervals, samples a single wavelength. The analysis of these observations, through a radiative transfer model [3], allows for the retrieval of key aerosol parameters such as aerosol opacity at different wavelengths (Figure 1) and particle radius (Figure 2). However, the continuous deposition of dust over the sensors [4], since the beginning of the mission, introduces modifications in their optical response. In particular, the zenith-pointed photodiodes require angular response calibration due to the progressive accumulation of dust on their optical surfaces. This calibration is essential to ensure the accuracy of aerosol property retrievals and the reliability of long-term atmospheric monitoring. Here, we present the ongoing development of our radiative transfer model for signal calibration, incorporating dust deposition corrections, along with preliminary results from the analysis of the initial sols of the Mars 2020 mission.

Figure 1. Retrieved aerosol optical depth at 650nm from sols 60 to 115, simulated using signals from MEDA-RDS TOPs 4, 5, 6, and 8 between 08:00–10:00 and 15:00–17:00 LTST.

Figure 2. Retrieved dust effective radius from sols 60 to 115, simulated using signals from MEDA-RDS TOPs 4, 5, 6, and 8 between 08:00–10:00 and 15:00–17:00 LTST.

[1] Apestigue, V., et al. “Radiation and Dust Sensor for Mars Environmental Dynamic Analyzer Onboard M2020 Rover”. Sensor 22.8 (2022): 2907.

[2] Rodriguez-Manfredi, Jose Antonio, et al. “The Mars Enviromental Dynamics Analyzer, MEDA. A suite of enviromental sensors for the Mars 2020 mission.”Space science reviews 217.3 (2021): 1-86.

[3] Toledo, D., et al. “Measurement of aerosol optical depth and sub-visual cloud detection using the optical depth sensor (ODS)”. Atmospheric Measurement Techniques 9.2 (2016): 455-467.

[4] Vicente-Retortillo, A., et al. “Dust Accumulation and Lifting at the Landing Site of the Mars 2020 Mssion, Jezero Crater, as Observed From MEDA.” Geophysical Research Letters 51 (2024).

How to cite: Rodriguez-Veloso, R., Toledo, D., Apestigue, V., Arruego, I., Lemmon, M. T., Smith, M. D., Martínez, G. M., Vicente-Retortillo, Á., Jiménez-Martín, J. J., García-Menéndez, E., Viudez-Moreiras, D., Sanchéz-Lavega, A., de la Torre-Juárez, M., and Rodríguez-Manfredi, J. A.: Aerosol optical properties observed by MEDA Radiation and Dust Sensor (RDS) at Jezero Crater, Mars, EPSC-DPS Joint Meeting 2025, Helsinki, Finland, 7–13 Sep 2025, EPSC-DPS2025-680, https://doi.org/10.5194/epsc-dps2025-680, 2025.

The MEDA instrument on Mars 2020 has been operating on the surface of Mars for more than 1500 sols obtaining measurements of pressure, temperature and other environmental properties with a fast cadence. Vortices and dust devils appear often in the MEDA measurements obtained by the pressure sensor and the Radiation and Dust Sensor (RDS) suite, and the vortex signature is some times present in other MEDA sensors, particularly on the Thermal and Infrared Sensor (TIRS). Current data covers a period of nearly 2 Martian years that allows a deep investigation of the properties of dust devils on the Jezero area. We identify the close approaches of vortices to the Perseverance rover from pressure drops measured with MEDA and identified by a search algorithm that uses a variety of time windows to find and characterize both short and long pressure drops [1, 2]. Some of these vortices are identified as dust devils from simultaneous or nearly simultaneous drops of light measured by the RDS Top sensor [3].

Seasonal variability repeats similarly over 2 Martian Years but interannual variability is also observed. Dust devil activity peaks over summer at Ls=150º-160º and strongly declines in the autumn to early winter season, especially during Martian Year 37 around sol 1200 of the mission. The inter-annual variability is linked to varying properties of the terrain over the traverse followed by Perseverance as it explores different terrains from the crater floor to the crater rim and the delta over an accumulated distance of 35 km. Some particularly intense events with pressure drops as deep as 7.7 Pa raise significant amounts of dust. The trajectory of these very strong dust devils can be studied by the RDS lateral sensors, thus, constraining the geometry of the encounter and the physical properties of the dust devil. A combined dataset of nearly 4,000 vortices and nearly 700 dust devils will be presented. For a small subset of events, we investigate ranges of models of drifting vortices that can fit the diameter and closest approach to the vortex encounter from the combination of pressure and RDS data.

References: [1] Newman et al. The dynamic atmospheric and aeolian environment of Jezero crater, Mars.Science Advances, 8, eabn3783 (2022) 25 May 2022, doi: 10.1126/sciadv.abn378 (2022). [2] Hueso et al. Convective vortices and dust devils detected and characterized by Mars 2020, Journal of Geophysical Research Planets, 128, e2022JE007516, https://doi.org/10.1029/2022JE007516 (2023). [3] Toledo et al. Dust devil frequency of occurrence and radiative effects at Jezero crater, Mars, as measured by MEDA Radiation and Dust Sensor (RDS) Journal of Geophysical Research: Planets, 128, e2022JE007494, doi: https://doi.org/10.1029/2022JE007494 (2023).

How to cite: Hueso, R., Newman, C., Toledo, D., Martínez, G., Munguira, A., Apéstigue, V., Vicente-Retortillo, Á., Sánchez-Lavega, A., and del Río-Gaztelurrutia, T.: An Updated Catalog of Vortices and Dust Devils on Jezero Crater, Mars from MEDA data, EPSC-DPS Joint Meeting 2025, Helsinki, Finland, 7–13 Sep 2025, EPSC-DPS2025-343, https://doi.org/10.5194/epsc-dps2025-343, 2025.

With the success of the Ingenuity helicopter onboard the Perseverance Rover, there is increased interest in exploring aerial vehicle concepts to assist with long-range reconnaissance and geological sampling on Mars [1]. Preliminary studies of more capable rotorcraft have suggested that such craft could carry science payloads of at least 2 to 5 kg at altitudes of at least 200 m along ranges of at least 1 to 5 km [2,3]. Clearly, such a vehicle could revolutionize our exploration of the martian surface.

However, a next generation rotorcraft could also revolutionize our understanding of the near-surface martian atmospheric planetary boundary layer (PBL). This layer is largely inaccessible to orbiters and landers, yet links the datasets obtained by both. Within this zone, dust is lifted and deposited, water ice sublimates and falls as snow, and gas-solid chemistry alters the mixture of trace gasses within the bulk atmosphere [4,5]. Furthermore, any gasses which vent from the subsurface will form a plume within this layer that is detectable at large distances, allowing such vents to be localized for follow-on in-situ exploration.

This presentation will therefore outline atmospheric science goals that could be accomplished from a rotorcraft [2,3]. These goals will be divided into four categories

Meteorology: Meteorological packages can be compact providing high-frequency in-situ data on atmospheric parameters (e.g. [6]) while generating relatively little data volume. The most advantageous parameters to measure would include (1) single or multi-axis measurements of wind speed and direction, e.g. from sonic anemometers, (2) temperature, (3) pressure, (4) relative humidity and (4) upwelling or downwelling radiometry in a variety of wavebands, e.g. by photovoltaic sensors.

These measurements could be used to improve numerical models of the atmosphere. Vertical profiles of meteorological parameters would be particularly useful. For instance, by determining the wind profile, friction velocities can be obtained which will inform studies of aeolian transport of materials in the near surface. Relative humidity as a function of height can be used to examine surface-atmosphere exchange of water. Pressure and temperature can be used to profile the cores of dust devils. Changes in upwelling and downwelling radiation as altitude changes provides information on atmospheric aerosol radiative properties.

Dust and Ice Cloud Aerosols: The rotorcraft will need a downward facing camera not just for reconnaissance but also to be able to position itself relative to the landscape. Previous spacecraft cameras have shown themselves to be adept at retrieving the optical depth of dust at different layers within the atmosphere [7] and by allowing the rotorcraft to vary its altitude, a full tomographic profile of atmospheric dust can be obtained. However, beyond imaging clouds and dust directly, more active sensing techniques could be considered. For instance, a lidar or small laser could induce backscattering from dust or ice aerosols, allowing low-altitude clouds, fog, or dust plumes/devils to be investigated in situ. A nephelometer [8] could be used to observe the scattering properties of the aerosols, obtaining particle size and shape as a function of altitude.

Trace Gasses and Fluxes: While many atmospheric gasses have been quantified from orbit, the processes that take place within the PBL prevent these gas concentrations from being directly compared to landed measurements and to subsurface fluxes. For instance, TGO is incapable of observing the methane that is regularly seen by the Curiosity rover at Gale Crater [9,10]. Somewhere between the rover and the airmass aloft being sampled by the orbiter, the gas is chemically transformed [4]. Furthermore, there are changes observed in oxygen (the fourth most abundant atmospheric species), carbon monoxide [5] and peroxide that are poorly explored over altitude, to say nothing of isotopic ratios within each chemical constituent.

Measuring bulk composition and trace gas composition require different instrumentation. However, no matter the species, a great deal about surface chemistry on Mars could be learned by creating profiles at different times of day and season. Advanced spectroscopic systems using techniques such as OA-ICOS [11] allow measurements of even trace gasses to be performed on the scale of minutes using instruments capable of being carried aloft. The most tantalizing possibility here is the ability to use the capabilities of the rotorcraft to detect and localize subsurface vents by tracing gas plumes in the PBL.

Aeolian and Geophysical Platform: Rotorcraft also permit an ideal vantage point from which to observe aeolian systems and to perform geophysical measurements. A rotorcraft can observe ripple forms and can conduct change detection of aeolian features through repeat observations at locations beyond a rover’s line-of-sight even over terrain that is inaccessible to rovers. Meanwhile, modern gravimeters may be able to help identify different types of subsurface geology, including deep deposits of aeolian sediments or dust/loess. Magnetic field sensors could add richness to these datasets and have been entirely unexplored at these geographic scales on Mars previously.

Conclusion: Just as the InSight Lander was targeted as a pathfinder to demystify the deep Martian interior, a PBL explorer could address significant scientific questions about the atmosphere of Mars today. Modern instrumentation can enrich the science return from such a rotorcraft at relatively little cost, given the compact nature of most atmospheric instrumentation.

References: [1] Wadhwa and Farley (2022) AGUFM abstract P56A-03 [2] Withrow-Maser et al (2020) ASCEND 2020 Conference https://doi.org/10.2514/6.2020-4029 [3] Johnson et al (2020) NASA/TM-2020-220485 [4] Korablev et al. (2021) Science Advances 7(7) doi: 10.1126/sciadv.abe4386 [5] Trainer, M.G. (2019) JGR: Planets v124 (11) pp. 3000-3024 doi: 10.1029/2016JE006175 [6] Gómez-Elvira et al (2012) SSR 170 pp 583-640 [7] Smith et al (2020) JGRE doi: 10.1029/2020JE006465 [8] Ragent et al. (1996) Science 272(5263) pp 854-856 [9] Webster et al. (2018) Science 360 pp. 1093-1096 doi: 10.1126/science.aaq0131 [10] Korablev et al. (2019) Nature 568 pp 517-520 [11] Walters et al (2024) Acta Astronautica doi: 10.1016/j.actaastro.2024.02.031

How to cite: Moores, J., Bischof, G., Axelrod, K., Innanen, A., Dong, E., Hayes, C., Markovich, M., Newton, A., and Marincic, I.: At the altitude where it happens: science goals for exploring the martian boundary layer with rotorcraft, EPSC-DPS Joint Meeting 2025, Helsinki, Finland, 7–13 Sep 2025, EPSC-DPS2025-47, https://doi.org/10.5194/epsc-dps2025-47, 2025.

Please decide on your access

Please use the buttons below to download the supplementary material or to visit the external website where the presentation is linked. Regarding the external link, please note that Copernicus Meetings cannot accept any liability for the content and the website you will visit.

Forward to presentation link

You are going to open an external link to the presentation as indicated by the authors. Copernicus Meetings cannot accept any liability for the content and the website you will visit.

We are sorry, but presentations are only available for users who registered for the conference. Thank you.

Human missions to Mars will require detailed knowledge of local meteorological conditions. Continuous measurement of winds in the vicinity of a landing site is needed to provide accurate local weather monitoring and forecasting, thus preparing future expeditions to safeguard against the operational impact of hazardous dust events. These measurements are also required to ensure compliance with COSPAR planetary protection requirements regarding potential contamination of ‘special regions’ within the human exploration zone through the atmospheric transport of contaminants from human activities.

Key to understanding this local-scale atmospheric transport will be obtaining accurate measurements of the 3-D wind vector, most likely through a network of landers equipped with meteorological instrumentation. Here we build on a prior ESA internal study on a Mars Weather Network Mission to present an analysis of wind variability and reconstruction across six test-case landing sites - Chryse Planitia, Gusev and Schiaparelli craters, Mesopotamia, Mawrth Vallis and Hypanis Vallis - which have been proposed as future human exploration zones.

Local winds were simulated using the Laboratoire de Météorologie Dynamique Mars Mesoscale Model (Figure 1). An Empirical Orthogonal Function analysis was then performed, which decomposed the near-surface wind into orthogonal spatial patterns (EOFs). We found that the first 4 EOFs captured between 70-90% of wind variability at most sites.

By simulating continuous wind measurements from a network of four landers, we then calculated reconstructions of both the horizontal near-surface wind field as well as the full 3-D wind field for the first five kilometres above the surface. We found that Hypanis Vallis and Mesopotamia were the sites with the lowest reconstruction errors, and that reconstruction was poorer at sites with greater topographic variation such as the Gusev and Schiaparelli craters.

Our results provide the first quantification of wind field reconstruction error for meteorological monitoring using a network of landers on the Martian surface and therefore constitute a useful benchmark for future work.

Figure 1 - Sample simulation output of the 3-D wind field at Chryse Planitia. The wind field has been visualised by initialising 1,000 particles at random locations, then using a Lagrangian trajectory algorithm to calculate how the particles are advected by the wind field. Particles are coloured by wind speed.

How to cite: Rajendran, K., Holmes, J. A., Patel, M. R., Parfitt, C. E., Paardekooper, D., Ball, A. J., Svedhem, H., and Wilson, C. F.: Reconstructing martian winds at potential future landing sites with a regional lander network, EPSC-DPS Joint Meeting 2025, Helsinki, Finland, 7–13 Sep 2025, EPSC-DPS2025-715, https://doi.org/10.5194/epsc-dps2025-715, 2025.

Introduction

Dust deposition poses the challenges to the survival of instruments and solar-powered missions on Mars [1, 2]. Zhurong in-situ observations provide an opportunity to study dust dynamics. Here, we present the dust evolution at the Zhurong landing site by means of the deposited optical depth on the Multispectral Camera (MSCam) calibration target and dust factor measured by the solar panels.

In-situ observation

MSCam calibration target observation: the deposited dust would modify the reflectance properties of the MSCam calibration target. A dust correction model based on the two-layer radiative transfer model [3, 4] is applied to estimate the dust deposited optical depth on the MSCam calibration targets.

Solar panel observation: the progressive deposition of dust can also decline the solar panel current output. We calculate the dust factor, indicating the ratio of the measured power output to that of an array without any dust [5], to measure the dust accumulation on the rover.

Results and discussion

The dust deposited optical depths on the MSCam calibration target are very low for the first 110 sols (Fig. 1a), suggesting that there is almost no dust deposited on the calibration target or the deposited dust is too thin to modify the reflectance of the calibration targets. After the solar conjunction, dust starts to accumulate on the calibration target with a deposition rate of 0.12%-0.19% per sol. The dust factor derived from the solar panel exhibits a similar trend with the observation from the MSCam calibration target (Fig. 1b). The dust factor shows a relatively slow decrease for the first 200 sols with an exponential decay of 0.07% per sol but a severe decline after Sol 200 with a rate of 0.46% per sol .

The two separate observations reveal two distinct dust deposition stages at the Zhurong landing site: very slow dust deposition for the initial 200 sols, then followed by a significant acceleration in dust deposition rate after Sol 200. The increasing deposited optical depth and declining dust factor also suggest the lack of dust cleaning events during the 300 sols’ traverse.

Fig. 1 (a) The deposited optical depth on the MSCam calibration target as a function of time [6]. (b) dust factor derived from solar panels as a function of time [7]. The two vertical gray dashed lines represent the last MSCam observation before the solar conjunction and first observation after the solar conjunction, respectively. The black lines are dust factor exponential decline of two different stages, and the black dashed line shows a 0.18% per sol exponential decline of the first 300 sols observations.

References. [1] Landis, G. A. (1996). Acta Astronautica, 38(11), 885-891. [2] Johnson, J. R., et al. (2003). Icarus, 163(2), 330-346. [3] Johnson, J. R., et al. (2006). JGR: Planets, 111(E12). [4] Kinch, K. M., et al. (2015). ESS, 2(5), 144-172. [5] Lorenz, R. D., et al. (2021). PSS, 207, 105337. [6] Zhang, Q., et al. (2023). GRL, 50(13). [7] Zhang, Q., and Liu, J. (2025). Quaternary Sciences, 45(4).

How to cite: Zhang, Q. and Liu, J.: Dust deposition and lifting at the Zhurong landing site, EPSC-DPS Joint Meeting 2025, Helsinki, Finland, 7–13 Sep 2025, EPSC-DPS2025-1270, https://doi.org/10.5194/epsc-dps2025-1270, 2025.

Introduction

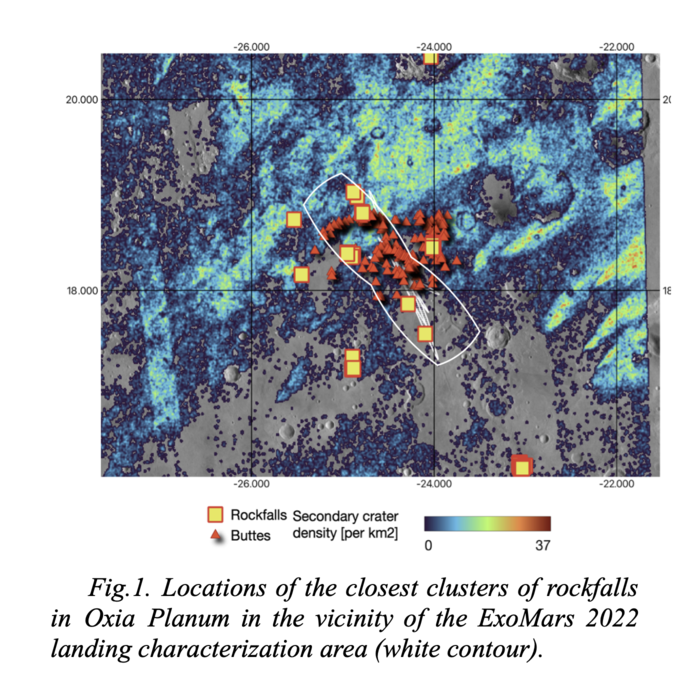

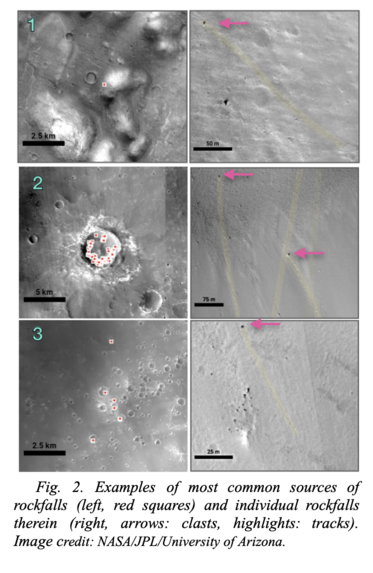

The solar-powered ESA ExoMars Rosalind Franklin (EMRF) rover will land in Oxia Planum in 2030. Given the importance of dust-lifting events in clearing solar panels for energy production on previous in situ missions [e.g. 1,2], it is vital to understand the likely frequency of such events at Oxia Planum. A global machine learning study found “3 small and 3 large” dust devils in the Oxia region over 8 Mars years [Conway, 2025]; of these dust devils, only one intersects the landing ellipses for the EMRF rover. Our earlier study in Oxia Planum found 2 active dust devils in a single High Resolution Stereo Camera (HRSC, [3]) image, and 4 active dust devils using a ratio of 2 Context Camera (CTX, [4]) images [5]. The aim of this study is to expand previous studies to identify active dust devils in Oxia Planum using all available orbital data, to determine the spatial and temporal distribution of possible dust lifting events in the landing site for the EMRF rover.

Data

Our analysis covers the time period May 2006 to April 2024, corresponding to Mars Years 28 to 37. Our study uses visible wavelength image data from instruments on three different spacecraft: HRSC on Mars Express, CTX (49 images) and High Resolution Imaging Science Experiment (HiRISE, [6]) on Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter, and Colour and Stereo Surface Imaging System (CaSSIS, [7]) on Trace Gas Orbiter.

The main study site was selected on the basis of maximizing the temporal range available for identifying dust devils in a representative part of the EMRF landing site. As such, our study focuses on the center of the landing ellipses, and contains the majority (69%) of the 1s landing ellipses as positioned at the time of this study. In addition, we used the InSight mission landing site as an area to test our methods in the same time periods used in a previous study using higher spatial resolution data [8].

Method

The main novelty in our approach is the rigorous coregistration, and, through the use of a stereo Digital Terrain Model (DTM), orthorectification of many overlapping CTX images. At the main Oxia study site, we produced 49 co-registered CTX orthoimages. At the InSight test site we produced 2 co-registered CTX orthoimages. We first identified changes between orthoimages by creating image ratios. Additional dust devils were also identified using an image ‘flicker’ approach. At Oxia Planum, we searched HRSC (11 images), CaSSIS (37 images), and HiRISE (50 images) image data for the presence of active dust devils. For HRSC and CaSSIS, we manually georeferenced images to our CTX orthoimages, and exploited the multispectral capabilities to help identify any active dust devils (e.g. [e.g. 9, 10]). For HiRISE, we used stereo pair anaglyphs to look for evidence of change between images. Although our main goal throughout the study was to identify the presence of active dust devils, we also traced changing surface albedo features that correspond to dust devil tracks and/or wind streaks when possible [e.g. 5, 8].

Results

We identified a total of 37 active dust devils in the Oxia Planum study area. Of these dust devils, 32 were in CTX images, and 5 in HRSC images. We did not identify any active dust devils in our Oxia Planum study site in CaSSIS or HiRISE images. Dust devil diameters range from 30 to 200 m, with a mean and standard deviation of 110 and 48 m respectively. The velocity of dust devils identified in HRSC images ranged from 10 to 23 ms-1, and were moving in roughly NE or SE directions. Dust devil activity in Oxia Planum was concentrated in two seasonal periods, peaking at both Ls ~ 15° and 180°. Peak activity occurred in Mars Year (MY) 33 and 36, with 13 and 14 dust devils respectively. We identified almost 800 new dust devil tracks across 2 different time periods, which had mean directions of 92° and 94°, and median lengths of 1.9 and 1.8 km.

Figure 1. Examples of active dust devils identified in Oxia Planum in CTX images.

Implications

Using the mean dust devil diameters, and all track lengths from 2 different time periods, we can estimate the formation rate of dust devils in Oxia Planum. Inverting this formation rate gives us the clearing interval, as calculated at other landing sites on Mars [e.g. 11]. We estimate solar panel clearing intervals for the EMRF rover of 3708 to 4218 sols. For comparison, Spirit experienced a solar panel clearing interval of 100 – 700 sols [1].

References: [1] Lorenz R.D. & D. Reiss (2015) Icarus, 248,162-164. [2] Lorenz R.D. et al. (2021) PSS 207, 105337. [3] Jaumann R. et al. (2007) PSS 55, 928-952. [4] Malin M.C. et al. (2007) JGR 112, E05S04. [5] Favaro E.A. et al. (2021) JGR 126, 2020JE006723. [6] McEwen A.S. et al. (2007) JGR 112, E05S02. [7] Thomas N. et al. (2017) Space Sci. Rev. 212, 1897-1944. [8] Perrin C. et al. (2020) GRL 47, e2020GL087234. [9] Stanzel C. et al. (2006) GRL 33, L11202. [10] Rangarajan V.G. et al. (2023) Icarus 394, 115443. [11] Reiss D. & R.D. Lorenz (2016) Icarus 266, 315-330.

How to cite: Grindrod, P., Favaro, E. A., Balme, M., and Patel, M.: Long-Term Orbital Monitoring of Oxia Planum, Mars: Active Dust Devils at the ExoMars Rosalind Franklin Rover Landing Site, EPSC-DPS Joint Meeting 2025, Helsinki, Finland, 7–13 Sep 2025, EPSC-DPS2025-128, https://doi.org/10.5194/epsc-dps2025-128, 2025.

Aeolian Landforms in the ExoMars 2028 Landing Site

Intro & Methods

ESA’s ExoMars Rosalind Franklin Mission will land a rover at Oxia Planum to search for signs of life on Mars [1, 2]. Bright bedforms (Transverse Aeolian Ridges [TARs]), and erosive wind-formed ridges (Periodic Bedrock Ridges [PBRs]) have been documented in the landing site [3-6]. In this study, we compare automated and manual mapping of aeolian features in CTX (6 m/pixel), CaSSIS (5 m/pixel) and HiRISE (25 cm/pixel) images in the landing site with sand fluxes from the NASA Ames GCM [7] obtained with the Martian Surface/Atmosphere Web Interface [8]. In particular, we focus our attention on bright bedforms, ridges and wind streaks. Since these features are widespread on Mars, the observations made here on ridge and bedform are also relevant to other areas and landing sites [9-13].

Results

Different aeolian features are observed in the landing area thanks to the new automatic mapping methodology employed in this work (Fig. 1a). Wind streaks (n = 87) were manually mapped on the CTX image mosaic [15] in a GIS environment. Most of the mapped streaks are bright-toned (n = 85), indicating winds originating from the NNW–NNE (Fig. 1b, c). A few dark-toned streaks (n = 2), formed by winds from the E–ESE, were also identified. Bright bedforms (TARs) were automatically mapped within the study area using the method described in [16]. They are widespread, especially in the SE, suggesting a higher sand supply and availability. Ridges (PBRs) were automatically mapped as well (Fig. 1a). These features are bright-toned as they are directly carved into the clay-enriched Noachain bedrock [4-6]. Together with the bright-toned ridge set, here we identified a new class of WNW–ESE-oriented cratered ridges (Fig. 1d). These features are mostly located in the NW of the study area but can also be found elsewhere. Theses sets of ridges display Y-junctions, can be found inside degraded impact craters, and may be locally covered by boulders from nearby impacts [4]. However, unlike PBRs, they are not directly carved into the underlying bedrock (Fig. 1d).

Discussion

The consistent orientation of bright wind streaks in the study area suggests contemporary regional winds predominantly blowing from the north, corresponding to the return flows of the Hadley cell circulation [17]. We also identified a secondary mode formed by winds from the ESE. Interestingly, a bimodal sand flux direction is also predicted by the GCM (Fig. 1e), with one mode (~172°–188°) closely matching the observed bright-toned wind streak orientations (Fig. 1b, c). This, along with no observed changes in orientation or modification of the bright streaks, indicates that these winds continue to blow at the surface and/or that winds from other directions are not strong or frequent enough to rework the wind streaks.

Bright bedforms (TARs) are likely relict or static features shaped by past wind conditions [4, 5]. This is supported by the GCM-predicted bedform orientation (red line in Fig. 1e), which does not align with either the observed TARs’ orientation or that of the older periodic bedrock ridges (PBRs) [4-6].

The newly segmented “Ridge 2” class of landform has previously been interpreted as precursor bedforms that initiated the formation of the underlying PBRs [4]. This interpretation is supported by (1) the close spatial association between PBRs and the “ridge 2” class, and (2) their similar orientation. However, in the example shown in Fig. 2, the ridges are located on a flat bedrock surface and are not associated with PBRs. The morphology of the “Ridge 2” class varies across the study area, with some ridges appearing subdued and eroded making them similar to ghost-dune pits [18]. Alternatively, such a relationship between positive and subdued morphologies might represent an assemblage of erosional scars and bedforms, similar to those observed at Meridiani Planum (see Fig. 6b in [10]). In this scenario, ridges are thought to have migrated southwest, leaving behind erosional scars.

Detailed examination of the relationships among ridges and TARs by the RFM rover will be crucial for advancing our understanding of ridges and PBR formation mechanisms [19, 20], the winds responsible for shaping TARs, and broader Martian climatic changes [9, 10].

Figure 1: (a) Automatically mapped ridges and TARs within the study area. (b, c) Wind streak in the landing area (CaSSIS RGB image MY35_007623_019_0). (d) WNW-ESE ridge 2 inside an eroded impact crater (HiRISE ESP_062481_1985). (e) GCM output at 18.2°N, 24.3°W. RDD = resultant drift direction [21]. Red line = predicted orientation (bed-instability mode) [22, 23]. "Finger direction" (fingering mode) [23].

References

[1] Vago J. et al. (2017). Astrobiology, 17. [2] Quantin et al. (2021), Astrobiology, 21. [3] Balme M. et al. (2017), PSS, 153, 39-53. [4] Silvestro S. et al. (2021), GRL, 48. [5] Favaro E. et al. (2021), JGR, 126. [6] Favaro E. et al. (2024), EPSL, 626. [7] Haberle R.M. et al. (2003), Icarus, 161. [8] Grasso F.M. et al. (2025), this issue. [9] Golombek M. et al. (2010), JGR, 115, 1-34. [10] Fenton L.K. et al. (2018), JGR, 123, 1–15. [11] Stack K.M. et al. (2022), JGR, 127, e2021JE007096. [12] Sullivan et al. (2022), 53rd LPSC, 2887. [13] Lu Y. et al. 2022, EPSL, 595, 117785. [14] Gou S. et al. 2022, EPSL, 595, 117764. [15] Fawdon et al. (2024), Journal of Maps, 20(1), 2302361. [16] Vaz D.A. et al. (2023), EPSL, 614. [17] Greeley et al. (1993), JGR, 98, E2, 3183-3196. [18] Day M.D. & Catling D.C. (2018), JGR, 123. [19] Montgomery D.R. et al. (2012), JGR, 117, E03005. [20] Hugenholtz C.H. et al. (2015), Aeol. Res., 18, 135–144. [21] Fryberger S.G. & Dean G. (1979), USGS prof. paper, 1052. [22] Rubin D.M. & Hunter R.E. (1987), Science, 237. [23] du Pont S.C. et al. (2014), Geology, 42.

Acknowledgement: The results were obtained in the context of the Earth-Moon-Mars (EMM) project (INAF/ASI & CNR), funded under the National Recovery and Resilience Plan, Mission 4, Component 2, Investment 3.1: “Fund for the realisation of an integrated system of research and innovation infrastructures" Action 3.1.1, NextGenerationEU.

How to cite: Silvestro, S., Vaz, D. A., Grasso, F. M., Rizza, U., Fenton, L., Pacifici, A., Tirsch, D., Favaro, E., Tao, Y., Salese, F., Popa, C., Franzese, G., Mongelluzzo, G., Porto, C., Pajola, M., and Esposito, F.: Aeolian Landforms in the ExoMars 2028 Landing Site, EPSC-DPS Joint Meeting 2025, Helsinki, Finland, 7–13 Sep 2025, EPSC-DPS2025-53, https://doi.org/10.5194/epsc-dps2025-53, 2025.

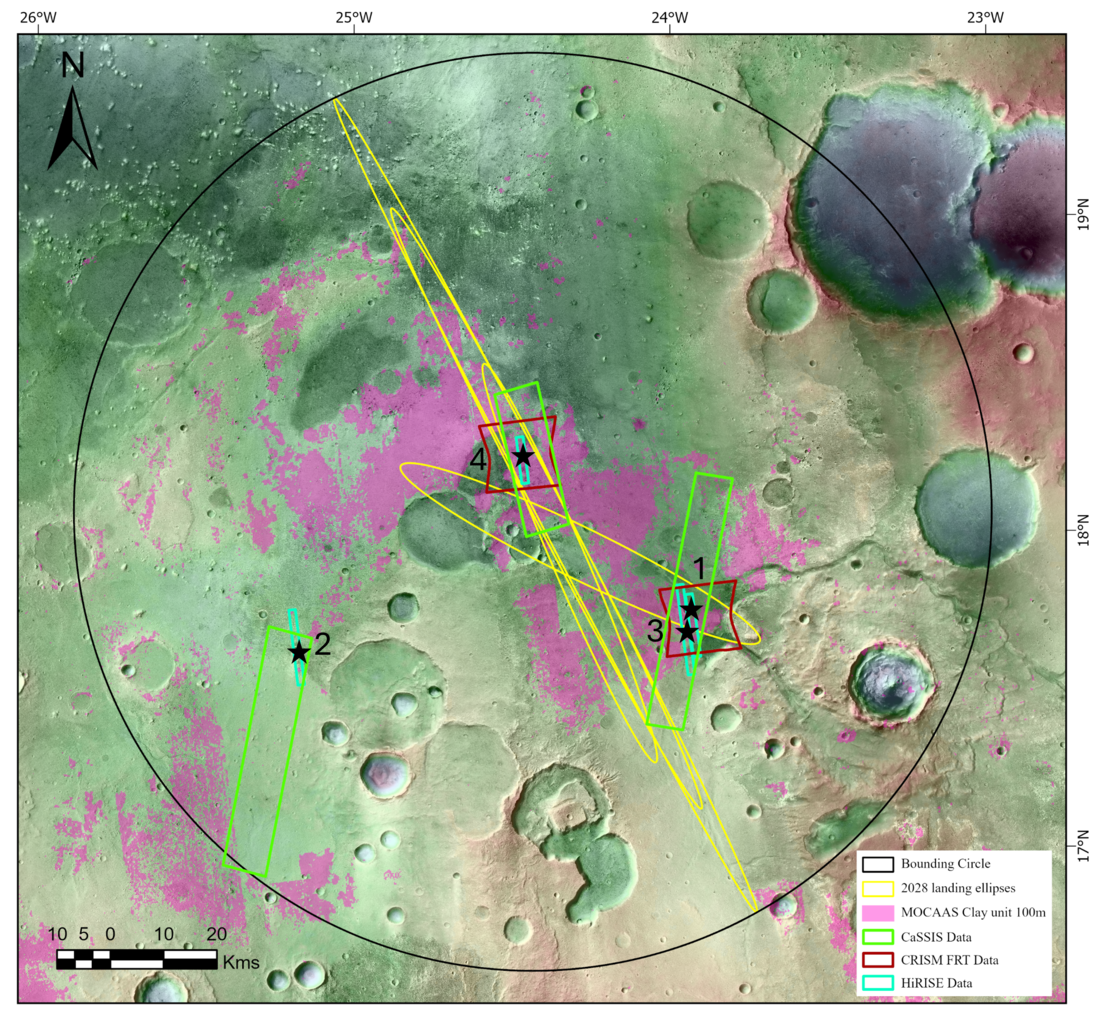

Oxia Planum is the chosen landing site for the European Space Agency’s ExoMars Rosalind Franklin rover mission for its evidence of multi-episodic sustained aqueous activity and astrobiological potential[1,2]. Previous works have aimed to characterise various mineralogical and morphological units present in Oxia Planum. Two distinct clay-bearing units have been identified based on spectral and morphological variations: an orange and a blue unit [2,3]. The blue unit stratigraphically overlies the orange unit, and while they are similar texturally, they exhibit some subtle textural as well as spectral differences from one another.Compositionally, the orange unit is associated with the strongest clay signatures, while the blue unit appears to be consistent with a clay signature mixed with a mafic component[2,3]. Several hypotheses have been proposed to explain their formation, including pedogenesis, groundwater alteration, and subaqueous sedimentation of either authigenic or clastic nature[3]. However, these scenarios need to be further constrained and may also need to be further expanded to include clay formation under less warm and wet conditions on early Mars [4]. Impact craters serve as windows into the subsurface by excavating, uplifting, and exposing materials that may not be visible at the surface. In this study, we use impact craters to investigate local and regional variations in the stratigraphy of Oxia Planum.

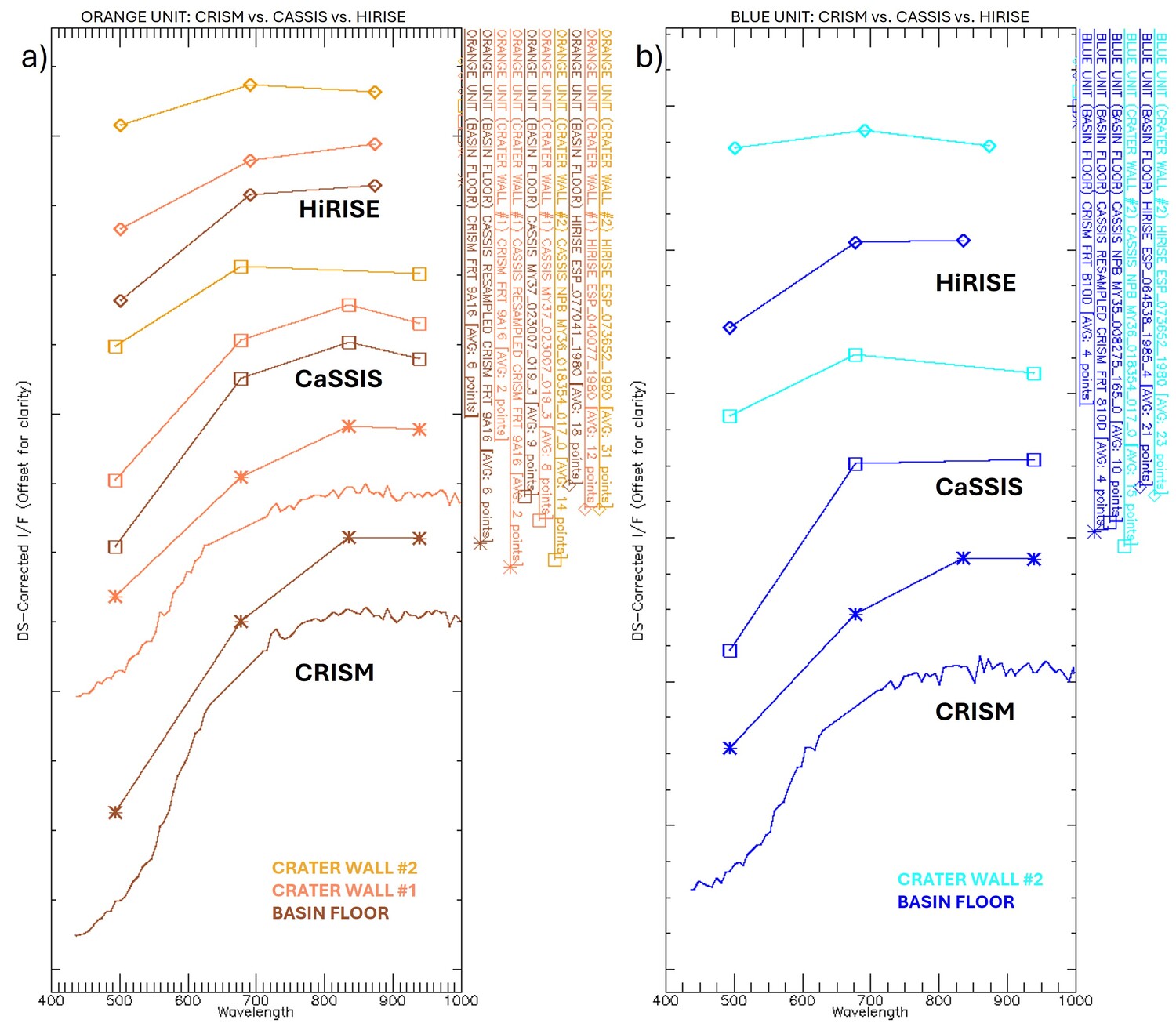

Methods: We characterized the colour/spectral characteristics of exposed layers within a ~1.5- and a ~2.1-km crater and compared them with units on the basin floor (stars in Fig. 1). Here we use DS-corrected [8-10] multispectral data from the 3-band High Resolution Imaging Science Experiment (HiRISE) (50-60 cm/px) [11], the 4-band Colour and Stereo Surface Imaging System (CaSSIS) (4 m/px) [12], and the hyperspectral Compact Reconnaissance Imaging Spectrometer for Mars (CRISM) (20 m/px) [13]. CRISM is no longer operational, and the data is limited, while CaSSIS and HiRISE effectively extend the detailed spectral information from CRISM across the region. By identifying specific mineral phases with CRISM and then spectrally resampling them to CaSSIS and HiRISE, we establish a method to extensively map mineralogical units.

Representative orange and blue unit CRISM spectra (FRTs 9A16 & 810D) were collected from sites 1,3 and 4 (Fig. 1) and resampled to the responses of CaSSIS for direct comparisons with image-derived CaSSIS and HiRISE spectra [14,15].

Fig. 1. HRSC-MOLA overlain on CTX and with a spectral map of clay detections in magenta[16]. The latest 2028 landing ellipses (yellow) and bounding circle (black) are shown. Black stars indicate the locations of craters (1 & 2) and basin floor (3 & 4) for spectral analysis.

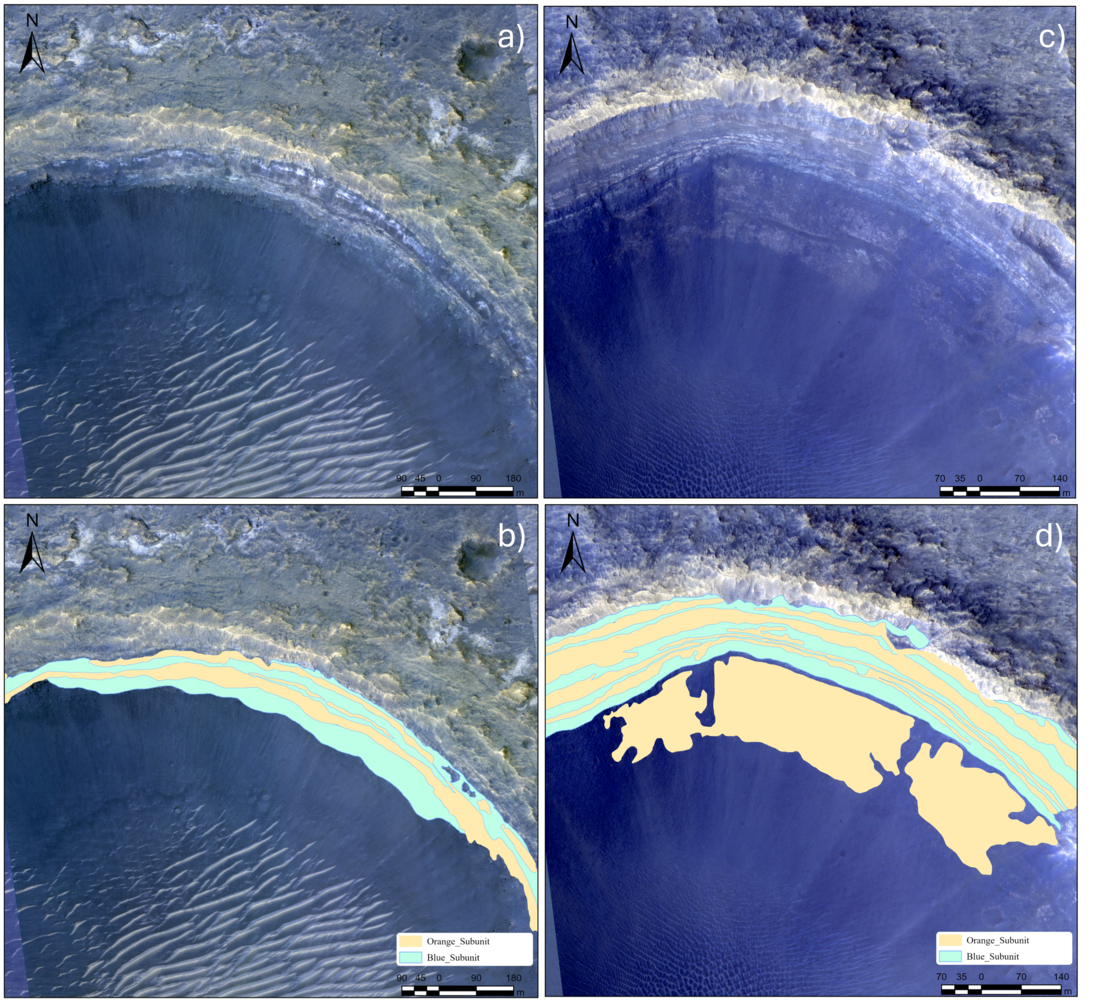

Results and Discussion: Previous mapping [5], reveals as many as 7 orange and 5 blue layers to date (location 2) (Fig. 2). Crater rim formation is a complicated process with the possibility of an overturned strata. However, any overturned flap would be limited to the uppermost section of the crater wall.

Fig. 2 Crater wall exposures. (a), (b) HiRISE IRB ESP_073652_1980 location #1 with mapped units; (c), (d) HiRISE IRB ESP_077041_1980 location #2 with mapped units.

The presence of multiple alternating layers raises questions about their origin—whether they represent the same or different units—and how these materials have evolved over time. Our spectral results show overall consistency in spectral shape between the three datasets, despite differences in their spectral and spatial resolution.

Fig. 3. Comparisons of DS-corrected CRISM (solid lines), CRISM resampled to CaSSIS (asterisk), CaSSIS (squares), and HiRISE (diamonds) spectra of the (a) orange unit and (b) blue unit from crater walls #1 and #2 and basin floor #3 and #4.

We compared the orange and blue units present in the basin floor (#3 & #4) and the crater walls (#1 & #2). The spectra show generally consistent nature of the units in the VNIR wavelengths. Contrary to the reported olivine component in the blue unit, the 810D spectra do not show any significant deflections towards the IR (#4; Fig. 3) [3]. Similarly, the blue unit lacks an IR deflection at ~950 nm in CaSSIS and HiRISE. It has a striking similarity with the orange unit which warrants further investigation. Due to the coarse resolution and limited coverage of CRISM, we could not extract a representative spectrum for the blue unit from the crater walls.

Well-exposed craters at lower elevations expose thicker units than ones at higher elevations (Fig. 3). These observations provide further constraints on the origin of the clays and favour a formation by erosion-transport-deposition sourced from the adjacent Noachian highlands, transported through valley systems, and eventually deposited in Oxia Planum [5].

We observe multiple alternating orange and blue units in craters across the Oxia Planum regionthat vary in number and thickness as a function of the location and local elevation [5,6], which differs from previous reports of one blue unit atop a singular orange one [2,3,7]. By further establishing a correlation between the number and thickness of these units as a function of location and elevation, we intend to reconstruct the clay-associated stratigraphy of Oxia. This would provide further insights into the provenance and origin of the clay units of the Oxia basin and the surrounding region.

References: [1] Vago J. L. et al. (2017) Astrobiology, 17 (6-7), 471-510. [2] Quantin-Nataf C. et al. (2021) Astrobiology, 21(3), 345-366. [3] Mandon L. et al. (2020) Astrobiology, 21(4), 464-480. [4] Tornabene L. L. et al. (2013) JGR: Planets, 118, 994–1012. [5] Srivastava et al. (2024) Xth Mars, 3233. [6] Srivastava et al. (2025) 56th LPSC, 1798. [7] Parkes – Bowen A. et al. (2022) PSS, 214. [8] Tornabene L. L. et al. (2018) Space Sci. Rev., 214. [9] Rangarajan V. G. et al. (2023) Icarus, 115849. [10] Tornabene L. L. et al. (2023) LPSC 54, p.2727. [11] McEwen A. S. et al. (2007) JGR: Planets, 112(E5), E05S02. [12] Thomas N. et al. (2017) Space Sci Rev, 212. [13] Murchie S. et al. (2007) JGR, 112, E05S03. [14] Tornabene L. L. et al. (2024) Xth Mars, 3318. [15] Tornabene et al. (2025) EPSC. [16] Carter et al. (2023) Icarus, 115164.

How to cite: Srivastava, A., Tornabene, L., Osinski, G., Caudill, C., Rangarajan, V. G., Fawdon, P., McNeil, J., Grindrod, P., Hauber, E., Davis, J., and Pajola, M.: Multi-scale Spectral Characterization of Clay-Rich Crater Walls in Oxia Planum, EPSC-DPS Joint Meeting 2025, Helsinki, Finland, 7–13 Sep 2025, EPSC-DPS2025-1001, https://doi.org/10.5194/epsc-dps2025-1001, 2025.

Introduction

The search for life is a key driver of Mars exploration, yet the detection of organic compounds on Mars remains sparse. High UV and ionizing radiation levels near the surface destroy organic compounds, leading to an underground search such as that planned for the Rosalind Franklin rover’s 2 m drill. Strong oxidizing agents have been suggested to explain conflicting Viking experiments’ non-detection results, adding further stress to any organic compounds. Such agents have since been identified in the form of perchlorate [ClO4-] salts in the martian regolith (Hecht et al. 2009). Nevertheless, small amounts of organic matter have been identified at the near surface in Gale crater on Mars with the Sample Analysis at Mars (SAM) instrument package on the Curiosity rover (e.g. Freissinet et al. 2025). However, it remains unclear whether these compounds formed on Mars or whether they are remnants of meteorite input. To tighten constraints on this assessment, we need to understand how the meteorite organic inventory evolves once it is exposed to the martian environment. Here we reacted organic compounds from a carbonaceous chondrite with perchlorate salts at levels measured in the martian regolith and analyzed the organic compounds before and after reaction with a non-targeted Liquid Chromatography Mass Spectrometry (LC-MS) metabolomics approach.

Materials and Methods

Crushed samples of the carbonaceous CM2 chondrite Jbilet Winselwan (JW) were exposed to magnesium perchlorate salts. This meteorite was found in the Western Sahara in 2013 and contains ~2 wt% organics. Measured amounts of perchlorate at the Phoenix landing sites are about 20 times the estimated amount of organic matter from meteorite input. The crushed meteorite samples were exposed to 1x, 20x and 100x perchlorate anion concentration treatments, meaning that the 20x treatment reflects the concentration on Mars. All experiments were conducted under anoxic conditions. Organics were then extracted with a series of non-polar to polar solvents and analysed with Hydrophilic Interaction Liquid Chromatography (HILIC) followed by mass spectrometry using an Orbitrap mass analyzer. Data was processed using MetaboAnalyst v6.0 (Scheltema et al. 2011; Smith et al.2006; Pang et al. 2024).

Results and Discussion

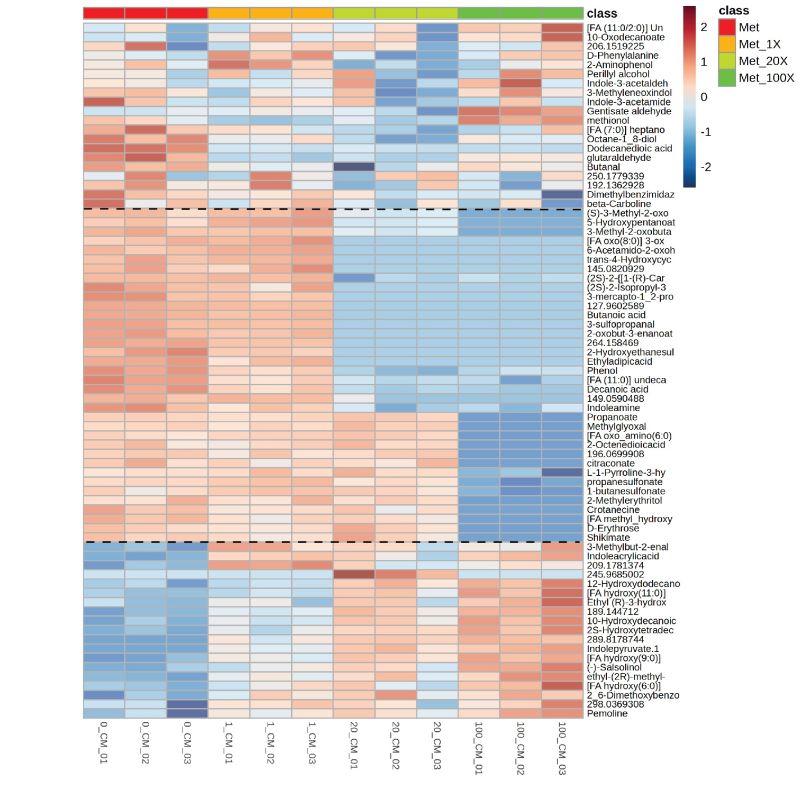

A Principal Component Analysis (PCA) was conducted on the LC-MS data to evaluate the effects of progressive perchlorate treatment on the JW meteorite organic inventory. The first two principal components account for 73.9% of the variance in the dataset (PC1: 59.5%, PC2: 14.4%). The trend in PC1 (Figure 1) reflects the treatment gradient across the experiment, with a vertical trend visible from untreated to 100x perchlorate treatment. In contrast, PC2 (14.4%) does not follow a linear pattern, with the 20x perchlorate treatment exhibiting positive loadings and the 100x exhibiting negative loadings, while untreated meteorite and 1x clustered around a loading of zero. We are investigating the possible causes for the organic distribution in 20X being so distinct from the 100X along the PC2 axis - particularly since the 20X concentration matches that of Mars - and will present the results of this work at the meeting.

Additionally we created a clustered heat map of the top 75 most abundant compounds in the perchlorate treatment experiment (Figure 2). The heatmap shows compounds behave differently when the meteorite is subjected to increased perchlorate treatment. Many compounds are resistant to smaller or moderate (20x) perchlorate treatments but are destroyed with 100x treatments. However, there are many compounds which increase in concentration with increased perchlorate treatment. This could be either liberation of compounds from macromolecule material or mineral matrix, or new compounds generated by in situ reactions during the course of the experiment. This result requires further investigation.

Conclusions

Our results indicate that Mars’ organic matter input from meteorites interacts with the martian environment, changing its composition. Inspection of individual compounds putatively detected suggest that some astrobiologically relevant compounds (e.g., N bearing polar molecules) are formed when perchlorate reacts with the CM2 organics, whilst others are destroyed.

LC-MS appears to maintain the structure of organic compounds despite the presence of oxidising agents. Our results suggest this technique reduces the detection ambiguity that would otherwise be associated with perchlorate oxidation and ultimately compound destruction in GC-MS ovens. This makes it a valuable tool for future Mars sample return.

References

Hecht, M.H. et al. (2009) Detection of Perchlorate and the Soluble Chemistry of Martian Soil at the Phoenix Lander Site. Science 325, 64-67.

Freissinet, C. et al. (2025) Long-chain alkanes preserved in a Martian mudstone. PNAS 122, 13 e2420580122.

Scheltema, R. et al. (2011) PeakML/mzMatch: A file format, Java library, R library, and tool-chain for mass spectrometry data analysis. Analytical Chemistry 83, 2786-2793.

Smith, C. et al. (2006) XCMS: Processing mass spectrometry data for metabolite profiling using nonlinear peak alignment, matching, and identification. Analytical Chemistry 78, 779-787.

Pang, Z. et al. (2024) MetaboAnalyst 6.0: towards a unified platform for metabolomics data processing, analysis and interpretation. Nucleic Acids Res 52, W398-W406.

Figure 1. PCA of the meteorite treatment. PC1 (59.5%) accounts for most of the variance with a clear progression of the perchlorate treatment. PC2 (14.4%) is less clear showing high variation at the extreme ends of the treatment.

Figure 2. A clustered heatmap of the concentrations of the compounds in the meteorite perchlorate treatment. The bottom section shows compounds that have increased with the increased addition of meteorite compounds. The middle section are compounds that are semi resistant or decrease with perchlorate treatment.

How to cite: Tait, A. W., O'Brien, A. C., Hallis, L. J., Morrison, D., Regnault, C., Blackburn, G., Hagermann, A., and Schröder, C.: Reaction of perchlorate with meteorite organic compounds – implications for organic molecule characterization on Mars, EPSC-DPS Joint Meeting 2025, Helsinki, Finland, 7–13 Sep 2025, EPSC-DPS2025-1224, https://doi.org/10.5194/epsc-dps2025-1224, 2025.

Introduction: The Fe-carbonate siderite has been detected in Gale crater by the CheMin instrument onboard the Curiosity rover at concentrations up to ~10.5 wt% [1,2] (Fig. 1, red stars). However, it remains undetected in orbital spectral data spanning 0.4–2.5 μm, even with recent advancements in CRISM data processing [3,4]. This discrepancy raises the possibility that spectral signatures of siderite in Mt. Sharp may be masked by other minerals present in the same strata. Notably, Mg-sulfates, occurring in amorphous form as well as kieserite and starkeyite, are abundant in these layers [1–3,5] (Fig. 1, shaded pink) and exhibit strong absorptions in the ~1.9–2.4 μm range, potentially interfering with the siderite diagnostic features near 2.3 and 2.5 μm.

Methods: We prepared five physical mixtures of Mg-sulfate and Fe-carbonate (siderite) powders in varying proportions to investigate whether Mg-sulfate can mask the orbital detection of siderite.

MicrOmega is a hyperspectral microscope operating in the infrared range (0.99–3.65 µm), offering a 5 × 5 mm² field of view and a spatial resolution of ~22 µm per pixel [6]. It is housed within the Planetary Terrestrial Analogue Library (PTAL) chamber, a large glove box continuously flushed with pure N₂. The chamber includes a movable sample platform that enables precise positioning, as well as temperature control to manipulate the hydration state of hydrous minerals. This configuration supports repeated imaging to capture both spatial heterogeneity and temporal changes during sample dehydration. For each sample, we acquired MicrOmega hyperspectral image cubes at three timepoints: at initial chamber exposure (t₀ = 0 hours), after 3 hours (t₁), and after 1 month (t₂). We calculated key spectral parameters to aid in grain identification and examined individual spectra to identify features at both the grain and full-image scales.

Results: In line with previous studies, the Mg-sulfate in our samples progressively dehydrates when exposed to the dry MicrOmega chamber environment [7,8]. MicrOmega spectral data indicate that the Mg-sulfate is initially present as epsomite (7 H₂O per formula unit) at t₀, transitions to starkeyite (4 H₂O) after 3 hours (t₁), and becomes largely amorphous (~2 H₂O) after 1 month (t₂).

Among the diagnostic siderite features, the 2.5 μm absorption is more readily detectable than the 2.3 μm band in our mixtures. While both features are evident in spectra of individual siderite grains, only the 2.5 μm band appears in the average spectra across the full MicrOmega field of view. This suggests that in a CRISM pixel (~18 × 18 m) where Mg-sulfate is present, the 2.3 μm siderite absorption may be obscured.

Our results also show that when Mg-sulfate is in its most hydrated form—crystalline epsomite—spectral features of siderite can be almost entirely masked, even in grain-specific spectra. In contrast, less hydrated forms such as starkeyite and amorphous Mg-sulfate are less effective at obscuring siderite’s spectral signatures.

Discussion & conclusions: These findings indicate that the presence of Mg-sulfate can obscure the key 2.3 and 2.5 μm carbonate absorptions commonly used in CRISM data to identify carbonates from orbit. In Gale crater, the presence of crystalline Mg-sulfate may be a contributing factor in masking the spectral signatures of siderite. Notably, all drill sites where siderite has been identified correspond to regions mapped as polyhydrated Mg-sulfate in CRISM data (Fig. 1).

While other factors, such as the low volumetric abundance of carbonates and grain-scale textural effects, may also contribute to the absence of carbonate absorptions in orbital observations, our results suggest that hydrated Mg-sulfate in upper Mt. Sharp plays a significant role. Elsewhere on Mars, similar sulfate-rich deposits may also obscure carbonate absorptions, particularly the 2.3 μm band and, to a lesser extent, the 2.5 μm feature, when carbonates are present at ~<25 wt%. This is relevant to other works that propose that major layered sulfate units could contain carbonates at levels comparable to those in Gale crater [2].

In sulfate-bearing terrains, particular attention should be given to the 2.5 μm band, as it may offer the only visible indication of carbonates. This is especially relevant for sites like Oxia Planum, where carbonate detections rely solely on a 2.5 μm feature without a corresponding 2.3 μm band [13]. Revisiting surface spectra to identify isolated 2.5 μm absorptions may provide new insights, especially considering the widespread nature of secondary sulfates on Mars and their impact on orbital carbonate detection.

References: [1] Thorpe et al., 2022, JGR Planets, 127, e2021JE007099. [2] Tutolo et al., 2025, Science, 388, 6744. [3] Sheppard et al., 2020, JGR Planets, 126. [4] Dhoundiyal et al., 2023, Icarus, 115504. [5] Fraeman et al., 2016, JGR Planets, 121. [6] Bibring et al., 2017, Astrobiology, 17, 621-626. [7] Sheppard et al., 2022, Icarus, 115083. [8] Chou et al., 2013, Journal of Asian Earth Sciences, 62. [9] Viviano-Beck et al., 2014, JGR Planets, 119. [10] Chipera et al., 2023, JGR Planets, 128. [11] Loizeau et al., 2020, Planetary and Space Science. [12] Farrand et al., 2024, AGU abstract. [13] Mandon, L., Parkes Bowen, A., Quantin-Nataf, C., Bridges, J. C., Carter, J., Pan, L., et al. 2021. Astrobiology, 21, 464–480.

Fig. 1: Orbital map of Curiosity drill holes. Samples where Curiosity detected Fe(II)-carbonate with CheMin [1] are marked with red stars and their abbreviated drill names: Glen Etive (GE/GE2), Mary Anning (MA/MA3), Groken (GR), Nontron (NT), Bardou (BD), Tapo Caparo (TC), Ubajara (UB), Sequoia (SQ). Samples where no carbonate was detected are marked with white circles. The drill holes are superimposed over HiRISE imagery and show in pink where orbital CRISM spectra show the presence of polyhydrated Mg-sulfate [3].

How to cite: Sheppard, R., Loizeau, D., Fraeman, A., Rampe, E., Pilorget, C., and Bibring, J.-P.: Sulfate can obscure spectral evidence of carbonate: MicrOmega observations with implications for Mars, EPSC-DPS Joint Meeting 2025, Helsinki, Finland, 7–13 Sep 2025, EPSC-DPS2025-1667, https://doi.org/10.5194/epsc-dps2025-1667, 2025.

Please decide on your access

Please use the buttons below to download the supplementary material or to visit the external website where the presentation is linked. Regarding the external link, please note that Copernicus Meetings cannot accept any liability for the content and the website you will visit.

Forward to presentation link

You are going to open an external link to the presentation as indicated by the authors. Copernicus Meetings cannot accept any liability for the content and the website you will visit.

We are sorry, but presentations are only available for users who registered for the conference. Thank you.

Introduction

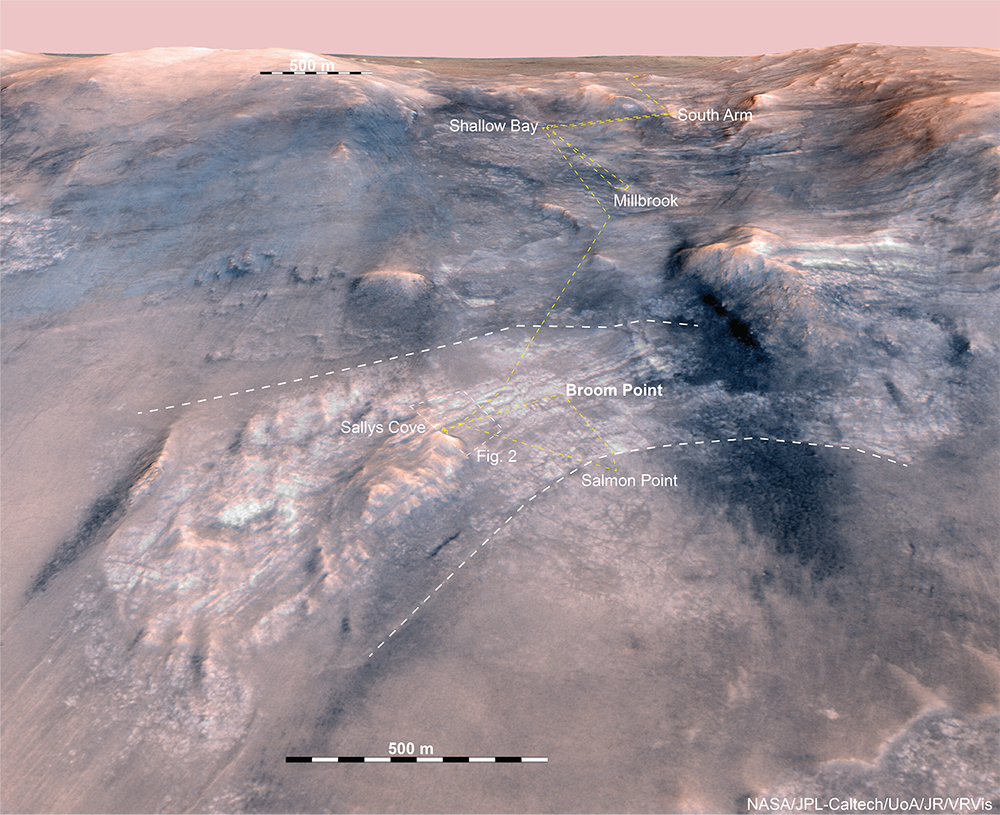

The Jezero fan delta has been well studied ever since the Mars 2020’s Perseverance rover landed in the crater in February 2021. There is now a comprehensive understanding of the architecture of the delta thanks to both in situ and orbital imagery; the fan formed in a closed lake as a Gilbert-type delta, showcasing the distinctive topset-foreset-bottomset tripartite [1].

Now that Jezero western fan is better understood, we would like to know if the Jezero delta architecture is relevant elsewhere on Mars: can we find similar geometries? Is Jezero the rule or the exception? To begin to try to answer this question, we focused on another martian sedimentary structure of similar size and volume: the Eberswalde sedimentary fan.

The Eberswalde crater (24.3° S, 326.5°E), located immediately northeast of the Holden crater, along the fluvial network connecting Argyre Planitia to Ares Vallis displays a spectacular fan shaped feature (~115 km²) with meandering channels in its westernmost part, that was most likely emplaced during the Late Noachian [2] in a closed-basin lake [3]. The volume of the fan is similar to that of Jezero’s western delta, the thickness of sediment is about 50 to 100 m in both cases [2], which makes it an interesting starting point for the comparison of Jezero to other martian sedimentary fans.

Methods

This study focuses on the geomorphological and stratigraphic analysis of the Eberswalde fan using orbital imagery. The HiRISE coverage of the Eberswalde crater is really good, due to the crater being previously considered among the potential landing sites of MSL and Mars 2020 missions. Thanks to HiRISE data, we have access to images with a resolution of up to 0.25 m/pix on the whole fan area.

The HiRISE orthoimages were taken as stereo pairs, which allowed creating stereo-derived DTM, giving access to topographic information. Contour lines and topographic profiles can therefore be extracted on the QGIS software. The dip angles of the outcropping layers can also be measured using the DTM on QGIS, thanks to the Three-Points-Method plugin, which extracts the elevation data from three points placed along the layer and calculates the dip angle and strike of said layer. Dipping layers were already observed by Goudge et al. (2018) [4] before rover data, showing that it is possible to observe them from orbit.

Results

On orbital imagery of the Eberswalde sedimentary fan, extensive meandering inverted channels are visible (Figure 1). It is possible to distinguish five lobes that were emplaced at different periods in time (Figure 1) [2]. The shape of the river channels on the Eberswalde fan differs from that of the channels on the Jezero delta, where they are rectilinear [5]. This indicates a difference in the fluvial regime responsible for the emplacement of these channels.

Figure 1: Map of the meandering inverted channels on the Eberswalde sedimentary fan and their stratigraphic relationships, from oldest to youngest lobes (coloured scale) [2]. White box represents the studied area of Figure 2. (HiRISE – MRO).

The beds outcropping at the front of the Eberswalde fan have dips mostly around 0° to 5°, occasionally reaching up to 8°, and almost always follow the contour lines (Figure 2a). These outcropping strata are therefore mostly subhorizontal, there are no steeply inclined layers at the front of the fan that would correspond to Gilbert-type foreset strata (Figure 2) as was observed in Jezero delta [1].

Two main phases can be distinguished from the orbital data: a lacustrine phase, with the subhorizontal beds outcropping at the front, and the fluvial (meandering) phase occurring afterwards.

Figure 2: (a) Close-up of an area on the Eberswalde sedimentary fan. Contour lines at 5 m are extracted from the stereo-derived HiRISE DTM (HiRISE – MRO). Red line: log line AA’ of the cross-section in (b).

(b) Interpreted cross-section of log AA’ with dip angles measured using the DTM reported on the section. Grey zone represents the lacustrine beds, blue the fluvial beds (recognizable also on the orbital imagery), and brown zone is the dust-covered areas. The red dashed line represents the possible discontinuity contact between the fluvial and lacustrine phases.

Preliminary conclusions

The stratigraphic and geomorphologic data of the present study indicate that the Eberswalde sedimentary fan did not emplace as a Gilbert-type delta, as is the case for the Jezero delta. It is therefore necessary to understand how the Eberswalde fan formed. Two hypotheses can be proposed:

- The fan emplaced in two separate phases, a lacustrine phase first, and a late-stage fluvial phase, emplacing the meandering rivers, with a gap between these two stages.

- Eberswalde is a shoal-water delta, that emplaced in a shallow lake, possibly as an aggradational delta [6], contrary to the progradational settings of the Jezero delta.

Those preliminary conclusions and hypotheses highlight the fact that the processes leading to the formation of the Eberswalde and Jezero fans are different, and the scenario of the Jezero delta should not be taken as the rule on Mars, although we have not explored more fans yet. The in-depth study of other martian sedimentary fans is fundamental for a better understanding of the availability of liquid water at the time they formed.

References

[1] Mangold N. et al. (2021) Science, 374, 711-717, doi: 10.1126/science.abl4051.

[2] Pondrelli M. et al. (2008) Icarus, 197, 429-451, doi: 10.1016/j.icarus.2008.05.018.

[3] Malin M. C. & Edgett K. S. (2003) Science, 302, 1931-1934, doi: 10.1126/science.1090544.

[4] Goudge T. A. et al. (2017) Earth and Planetary Science Letters, 458, 357-365, doi: 10.1016/j.epsl.2016.10.056.

[5] Kronyak R. E. et al. (2023) 54th LPSC, Abstract #2806

[6] Lewis K. W. & Aharonson O. (2006) J. Geophys. Res., 111, doi: 10.1029/2005JE002558.

How to cite: Carlot, N., Salese, F., Mangold, N., and Ori, G. G.: Stratigraphic analysis of the Eberswalde sedimentary fan using orbital imagery and comparison with the Jezero delta, Mars, EPSC-DPS Joint Meeting 2025, Helsinki, Finland, 7–13 Sep 2025, EPSC-DPS2025-92, https://doi.org/10.5194/epsc-dps2025-92, 2025.

Introduction:

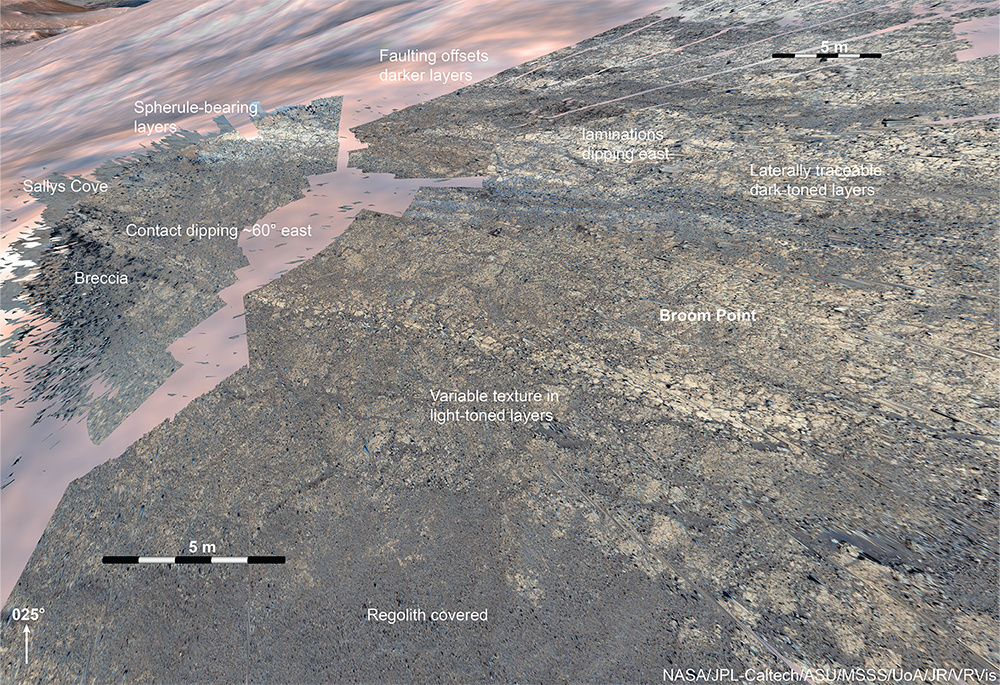

Fluvial valley networks on Mars provide key sites for investigating the role of surface liquid water in Mars’ ancient past. Between June and August 2024, the Perseverance rover spent 85 sols exploring a series of outcrops in Neretva Vallis, one of two inlet channels which provided water to the Jezero crater paleolake. These predominantly fine-grained sedimentary rocks comprise the “Bright Angel” formation [1], and the collection of an astrobiologically compelling sample from these rocks [2], motivates the development of a robust stratigraphic model to understand their emplacement. Here, we document the sedimentology and stratigraphy of the Bright Angel formation using Mastcam-Z landscape mosaics and derived 3D Digital-Outcrop-Models (DOMs) [3, 4], to constrain its depositional environment and sedimentary evolution.

Sedimentology and stratigraphy:

The Bright Angel formation comprises seven members (Figure 1). The base of the sequence comprises 1–10-cm-thick, planar-stratified rocks of the Tuff Cliff member, which exhibits at least one example of sub-rounded, pebble-sized clasts up to 2.5-cm-diameter (Figure 1B). These dark-toned rocks fine upwards into an ~8–10-m-thick succession of laminated mudstone (Figure 1C-D) variably cut by Ca-sulfate veins and nodules, with rarer dm-thick pebbly interbeds in its lower ~2m, termed the Walhalla Glades member. ~500 m west, at the northern contact of the Bright Angel formation with the Margin unit, a ~0.5-m-thick lens of monomict, matrix-supported olivine granule conglomerate is observed, named the Fern Glen Rapids member. This is overlain by a ~0.5 m thick mudstone with rare, coarser-grained, cm-thick olivine-rich horizons (Figure 1E), termed the Cheyava Falls member, which is overlain by the Walhalla Glades member. The Tuff Cliff member was not observed here. This succession is overlain and incised by an unstratified, unsorted, matrix-supported conglomerate exposed in the south of the channel (Figure 1F), termed the Mount Spoonhead member. The Serpentine Rapids (SR) member comprises a cross-stratified pebbly conglomerate (Figure 1G), lining the southern channel margin and appears to cap the sequence.

Figure 1: Geologic map and outcrop images of the members of the Bright Angel formation. (A) Structural-geologic map, (B) Contact of the Tuff Cliff and Walhalla Glades members, (C) Pebble-sized clasts in the Tuff Cliff member, (D) Contact of the Cheyava Falls and Fern Glen Rapids members, (E) plane-parallel lamination in the Walhalla Glades member, (F) Matrix-supported, conglomeratic texture of the Mount Spoonhead member, (G) Cross-stratified pebbly conglomerate of the Serpentine Rapids member. Image credits: NASA/JPL-Caltech/ASU/MSSS

Structural analysis and sedimentary successions:

Cross-sections were constructed using structural mapping from Mastcam-Z DOMs (Figure 2). Long-channel profile (A-A’) shows the Tuff Cliff member exposed in the east is likely buried beneath other members in the western Bright Angel outcrop. Cross-channel profile (B-B’) shows a fining-up sequence (from the Tuff Cliff to Walhalla Glades member), truncated by the Mount Spoonhead member conglomerates and Serpentine Rapids member cross-stratified conglomerates. A close-up of the northern exposure reveals an open, synform structure, with beds dipping into the channel. This apparent channel-infilling structure of the unit is supported by ground-penetrating radar acquired by RIMFAX [5], and appears consistent with the Bright Angel formation being younger than the Margin unit (although the contact is very poorly exposed at the surface). Structural data were projected across this structure onto an inferred fold axis, and assuming a constant bedding thickness, allowed the thickness of the mudstone succession to be estimated to at least ~10 m. Profile C-C’ shows that within ~2 m of the northern contact, bedding dips increase from 30˚ to >50˚ into the channel, exceeding the expected angle of repose and implying localised deformation [6].

Figure 2: Structural analyses of the Bright Angel formation, including long-channel profile A-A’, cross-channel profile B-B’ (with zoom of the northern section, showing a channel-filling bedding geometry), and zoomed profile C-C’ across the northern contact. Stereonet shows poles to bedding planes across the B-B’ section, and inferred “fold” axis.

Interpretation: The Tuff Cliff, Fern Glen Rapids, Cheyava Falls and Walhalla Glades succession is consistent with lacustrine deposition. The Tuff Cliff member conglomerates may reflect subaerial or proximal lacustrine deposition, and the fining-up into ~10 m of predominantly laminated mudstones (consistent with subaqueous suspension settling) may reflect a lake transgression. The matrix-support and compositional similarity of clasts in the Fern Glen Rapids and Cheyava Falls members to the Margin unit is consistent with local derivation from the valley walls, potentially as small debris flows. The very poor sorting and matrix-support of the Mount Spoonhead member is consistent with a mud-rich debris flow, with diverse clasts potentially sourced from the crater rim and beyond [7]. The Serpentine Rapids member cross-stratified conglomerates are consistent with unidirectional bedload transport in a fluvio-alluvial or fluvio-deltaic environment. Abundant Ca-sulfate veins in the lower stratigraphy supports burial depths sufficient for hydrofracturing.

This lacustrine environment occurs 10–50 m above the paleolake level implied by the Jezero western fan [8], suggesting the Bright Angel formation was deposited either (1) during a lake highstand, pre-dating breach of the eastern crater rim and western fan deposition [9], or (2) in a later-stage, valley-confined lake. The latter are common in terrestrial valley networks, where slope failure leads to channel blockage and formation of a lake upstream. These can produce successions similar to the Bright Angel formation [1,10], and may explain the absence of Bright Angel-like materials beyond Neretva Vallis. However, it remains unclear whether sufficiently thick deposits could accumulate to enable hydrofracturing of the lower members. Thicker deposits may accumulate in a more stable, pre-delta, lake highstand phase as proposed by [9]. In this model, the Bright Angel sediments may have been deposited up to 100 m below the highstand lake level [9].

References: [1] Jones et al., LPSC (2025), [2] Hurowitz et al., LPSC (2025), [3] Bell et al., Space Sci Reviews 217 (2021), [4] Paar et al., Earth and Space Science, 10 (2023), [5] Russell et al., AGU (2024). [6] Barnes et al., LPSC (2025), [7] Treiman et al. LPSC (2025), [8] Fassett and Head, Geophysical Research Letters, 32 (2005), [9] Salese et al., Astrobiology, 20 (2020), [10] Fort et al., Quaternary Research, 31 (1989).

How to cite: Jones, A., Barnes, R., Gupta, S., Paar, G., Horgan, B., Garczynski, B., Broz, A., Klidaras, A., Stack, K., Hurowitz, J., Russell, P., Bell III, J., Maki, J., Wogsland, B., Simon, J., Kanine, O., Mangold, N., Randazzo, N., Brown, A., and Flannery, D.: A fluvio-lacustrine environment preserved in the Jezero crater inlet channel, Neretva Vallis (Mars), EPSC-DPS Joint Meeting 2025, Helsinki, Finland, 7–13 Sep 2025, EPSC-DPS2025-888, https://doi.org/10.5194/epsc-dps2025-888, 2025.