Multiple terms: term1 term2

red apples

returns results with all terms like:

Fructose levels in red and green apples

Precise match in quotes: "term1 term2"

"red apples"

returns results matching exactly like:

Anthocyanin biosynthesis in red apples

Exclude a term with -: term1 -term2

apples -red

returns results containing apples but not red:

Malic acid in green apples

hits for "" in

Network problems

Server timeout

Invalid search term

Too many requests

Empty search term

MITM5

Session assets

The rapid advances in machine learning (ML) present unprecedented opportunities for planetary science. We have established a dedicated working group (WG) focused on the application of ML in this field to harness these technological advancements, address complex scientific questions, and enhance our understanding of planetary systems.

The Europlanet Machine Learning Working Group held its kick-off meeting during the EPSC 2024 in Berlin, September 2024. The discussion focused on launching the group for exchanging ideas and opportunities with people within and outside of Europlanet’s membership for the first year of its launch. Some of the main goals established were to create a knowledge-sharing platform for members to share their research and invite collaboration, form sub-groups within the WG to expand on current research focus, and foster new collaborative research opportunities within or outside of Europlanet with new funding.

As of May 2025, the Europlanet Machine Learning Working Group has 30 members. Better still, the group has so far been able to attract both senior and early career members.

The WG will build upon the achievements of the Europlanet RI project, which has addressed a broad range of ML applications across planetary research. The new group will delve deeper into specialized areas and foster collaboration and knowledge exchange. This targeted approach will enable the development of tailored ML solutions, drive innovation, and accelerate scientific discoveries.

Bridging the gap between ML and planetary science, the WG will position academic institutions and industry stakeholders at the forefront of cutting-edge research. The WG will develop

- ML methods and tools for planetary surface and subsurface mapping, mineralogy, geomorphology, and geology;

- apply ML techniques to planetary atmospheres, climates, and weather systems;

- study the formation and evolution of planetary systems, exoplanets, and astrobiology;

- create ML frameworks and platforms for data integration, fusion, visualization, and dissemination.

- Large Language Models (e.g., ChatGPT) will be utilized as tools for ML in planetary science.

Figure 1. Europlanet Machine Learning Working Group web page (https://www.europlanet.org/services/europlanet-machine-learning-working-group/)

The Machine Learning WG initiated regular monthly meetings on the third Wednesday of each month from January 2025 onwards, where members of the WG got an opportunity to present their current or published work followed by a Q/A session. On the Europlanet website(Fig. 1), you can see the scheduled meetings and speakers. We will highlight some of the talks given by our members. Membership in the WG requires being a member of Europlanet. Benefits include participating in high-impact, state-of-the-art ML science, sharing ML tools and facilities on the Europlanet ML Portal, developing collaborations, participating in future Europlanet EC-funded ML proposals, and accessing Europlanet ML training, career development, and professional services.

How to cite: Ivanovski, S. L., Verma, N., Hatipoğlu, Y., Angrisani, M., Solmaz, A., Smirnov, E., Carruba, V., Kacholia, D., Oszkiewicz, D., and D'Amore, M. and the Europlanet Machine Learning Working Group: Europlanet Machine Learning Working Group: a year of progress, EPSC-DPS Joint Meeting 2025, Helsinki, Finland, 7–13 Sep 2025, EPSC-DPS2025-1815, https://doi.org/10.5194/epsc-dps2025-1815, 2025.

The aim of this work is to present possible unsupervised machine learning methods, borrowed from the finance world, that can be applied to classify dynamical transitions appearing in the co-orbital motion.

Co-orbital dynamics appears in the three-body problem, and is widely studied to analyze asteroidal behaviors, but also to design trajectories for interplanetary missions. It can involve complex transitions that can be challenging to analyze manually due to large dataset, typically of planetary science, but also due to the role that different perturbations can play in the orbital evolution of real asteroids.

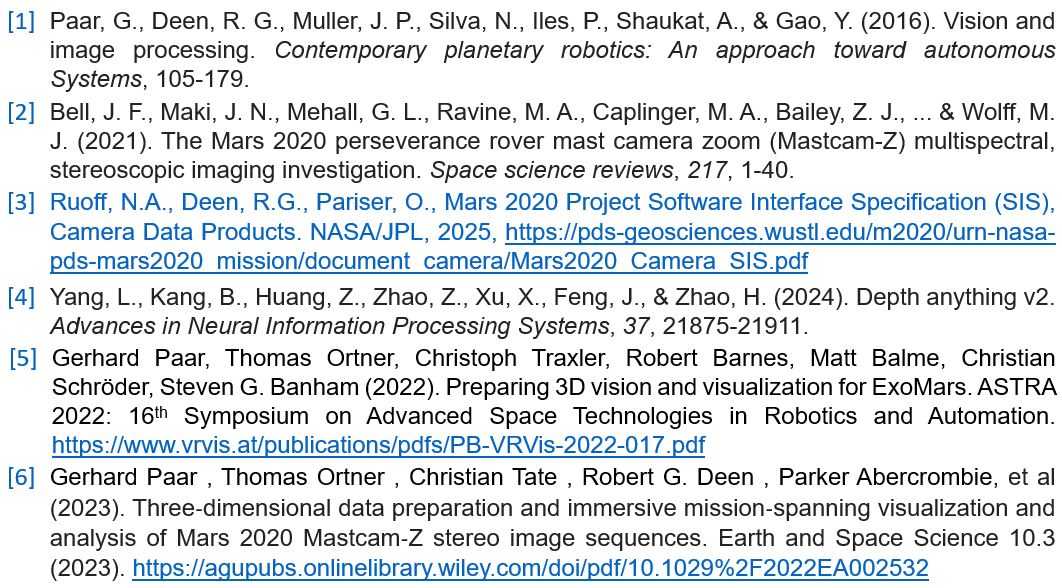

The method presented is the so-called statistical Sparse Jump Model (SJM) [1] and two novel improvements. The different formulations will be applied to medium-term time series of real asteroids and to long-term time series of simulated lunar ejecta, derived for [2]. The main orbital elements considered are the semi-major axis a, the resonant angle θ and the argument of pericenter ω. The focus will be to distinguish horseshoe (HS), quasi-satellite (QS), tadpole (TP) and compound (CP) behaviors in an automatic way and to provide meaningful metrics of the time permanence in a given regime.

The results on the behavior of lunar ejecta will be important in the context of the possible origin of important Earth's companions, like Kama'olewa or minimoons.

More details on the formulations implemented are given below.

Sparse Jump Model

The SJM takes as input a Tx P data matrix, where each row consists of given features of the system (function of a, θ and ω) at a given time t.

The model produces three main outputs:

- A sequence of latent states s = (s_1, ..., s_T), where each s_t represents a co-orbital regime (e.g., QS or HS).

- A set of centroids μ== (μ_1, ..., μ_K), with μ_k representing the most representative values for the state k.

- A feature importance vector w= (w_1, ..., w_P), where each w_p indicates the contribution of feature p to the system’s dynamics.

This is done optimizing an objective function with respect to centroids and latent states and depending on input data.

For details on model formulation and estimation, see [1,3]

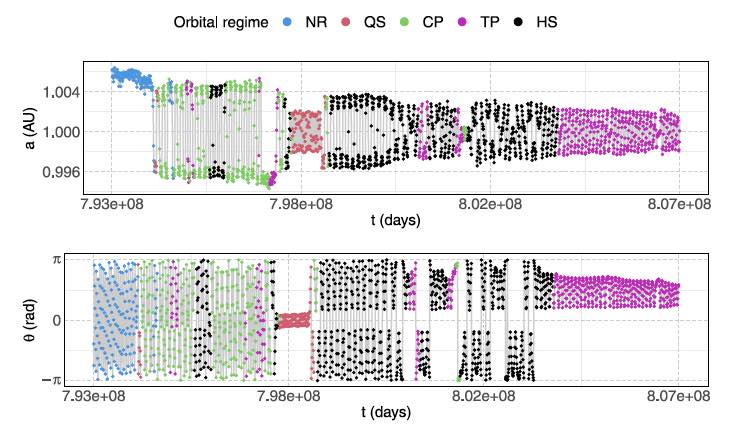

Figure 1, adapted from [4], illustrates the effectiveness of the SJM in identifying the orbital regime of a time series corresponding to lunar ejecta exhibiting a co-orbital behavior outside the Hill's sphere of the Earth [2]. As it can be seen, the case poses significant classification challenges, but the SJM delivers robust qualitative results.

Fuzzy Jump Model

A key limitation of the SJM is its reliance on hard clustering. To address this, we propose a novel extension - the Fuzzy Jump Model (fuzzy JM) - which introduces soft clustering capabilities into the SJM framework.

Our method incorporates a tunable fuzziness parameter that allows smooth transitions between hard and soft clustering. Inspired by the fuzzy c-means algorithm [5], we generalize the SJM to estimate time-varying state probabilities through numerical constrained optimization. To this end, the objective function is modified to take into account these probabilities.

Figure 2 illustrates the time-varying probabilities for the QS regime for the asteroid 164207 Cardea that transition between HS and QS phases.

During transition phases, the probability of switching from HS to QS evolves gradually, showing the ability of the model to anticipate transitions.

Robust Sparse Jump Model

A second limitation of the SJM is that feature relevance is assumed to be uniform across all states, that is, a variable selection is performed independently of the state classification.

To overcome this, we propose merging the jump model with the Clustering Objects on Subsets of Attributes (COSA) framework by [6]. In this novel framework, referred to as robust SJM, we estimate both the sequence of latent states and a state-specific feature weight matrix, where each entry quantifies the importance of a given feature within a given state.

These weights are found through a closed form formula. This formulation allows for feature selection within each state and guarantees convergence to a local optimum when the initial weights are uniform.

Acknowledgement: This work has been funded by the Italian Space Agency through the agreement n. 2024-6-HH.0, CUP n. F43C23000340001, entitled “Supporto scientifico alla missione LUMIO”.

References

[1] Nystrup, P., Lindstrom, E., Madsen, H. (2020). Expert Systems with Applications 150 , 113307

[2] Jedicke, R., et al. (2025). Icarus 438, 116587

[3] Nystrup, P., Kolm, P.N., Lindstrom, E. (2021). Expert Systems with Applications, 184 , 115558

[4] Cortese, F.P., Di Ruzza, S., Alessi, E.M. (2025). Nonlinear Dynamics, doi: 10.1007/s11071-025-11171-7

[5] Bezdek, J.C. (1981). Pattern recognition with fuzzy objective function algorithms. Springer Science & Business Media

[6] Friedman, J.H., & Meulman, J.J. (2004). Journal of the Royal Statistical Society Series B: Statistical Methodology 66 (4), 815–849

How to cite: Alessi, E. M. and Cortese, F.: A class of statistical jump models for the classification of dynamical transitions in the co-orbital regime, EPSC-DPS Joint Meeting 2025, Helsinki, Finland, 7–13 Sep 2025, EPSC-DPS2025-1465, https://doi.org/10.5194/epsc-dps2025-1465, 2025.

As astronomical surveys evolve to capture ever-larger volumes of data, innovative computational tools are increasingly critical for extracting meaningful signals from petabyte-scale datasets. Deep learning – machine learning algorithms that involve artificial neural networks – offers one such tool. Here, we present convolutional neural network-based approaches to enhance the discovery and recovery of asteroids in survey data. Our research utilizes two very different datasets: two decades of archival crowded field data from the Microlensing Observations in Astrophysics (MOA) survey and the ongoing Classical and Large A Solar System (CLASSY) trans-Neptunian objects survey.

Though designed to detect microlensing events in the Galactic Bulge and Magellanic Clouds, the MOA survey has incidentally observed several thousand asteroids in two decades of high-cadence imaging data. However, the extremely dense star fields posed a significant challenge to effectively identifying moving sources. To address this, we developed a novel approach that leverages the sky motion of asteroids in consecutive exposures to reveal its ‘tracklet’ – the linear motion path that highlights the asteroids’ movement against the static stellar background (Figure 1). These tracklets formed the basis of our labelled datasets of known asteroids, which we used to train several custom-designed convolutional neural networks (CNNs). We then ensembled the predictions from the best performing models to maximize accuracy and generalization, achieving a recall of 97.67%. In addition, we trained the YOLOv4 object detector to precisely localize asteroid tracklets, achieving a mean Average Precision (mAP) of 90.97%. We are now deploying these trained models across the full MOA data archive to identify both known and previously undetected asteroids – transforming the archival data into a powerful tool for asteroid discovery.

In parallel, we applied these deep learning techniques to the CLASSY survey, a Canada France Hawaii Telescope (CFHT) Large Program focused on finding distant TNOs. We labelled over ~75,000 composite images from nightly MegaCam observations, creating a training dataset that spans a variety of asteroid populations, including near-Earth objects, main belt asteroids, centaurs, as well as both real and simulated fast-moving TNOs. Our custom CNNs successfully detected tracklets across these diverse sources, and we once again combined the models to enhance predictive performance and minimize false negatives, achieving a recall of 98.15%. The labelling process highlighted the exceptional depth and clarity of the CLASSY observations as well as the effectiveness of the tracklet approach to identify a diverse range of solar system objects. We are now focusing our efforts on recovering centaurs – which are difficult to isolate because of the vast region they inhabit – from the observations.

While our work with CLASSY offers a framework for applying deep learning to future surveys like the Legacy Survey of Space and Time (LSST), the MOA archive uniquely demonstrates the untapped potential of archival microlensing datasets. Our results demonstrate the effectiveness of building targeted training datasets and applying model ensembling to maximize discovery. Together, these strategies offer a practical blueprint for integrating artificial intelligence into the data pipelines of future surveys, ensuring that the scientific potential of next-generation observatories is fully realized.

How to cite: Cowan, P., Bond, I., Fraser, W., Lawler, S., and Rattenbury, N. and the The MOA and CLASSY Collaborations: Towards asteroid discovery with deep learning in large datasets, EPSC-DPS Joint Meeting 2025, Helsinki, Finland, 7–13 Sep 2025, EPSC-DPS2025-1073, https://doi.org/10.5194/epsc-dps2025-1073, 2025.

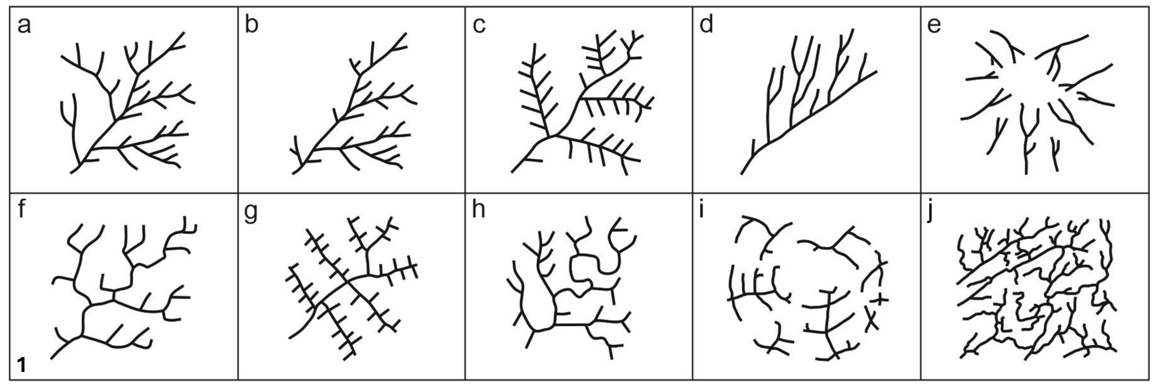

Asteroid families are groups of asteroids that have formed from the fragments of a larger ‘parent’ body that has been disrupted. When viewed in a space with the axis of proper orbital elements: semi-major axis (a), eccentricity (e), and inclination (i), families appear as relatively compact clusters within a background of unrelated asteroids. Halos are dense shells of asteroids that surround these families and tend to have similar properties to the core family yet are not considered as members. Isolating these halo structures and predicting their family membership remains and ongoing challenge. We present the results of using artificial neural networks (ANNs) aiming to solve this.

In this work we focused on C-type families in the inner-main belt, between 2.1 and 2.5 au. C-type families are notably dark, with reflectance less than 5-10% and are distinctive from the backgrounds they are situated in. This is useful for verifying the predictions of the ANNs. The Erigone family was focused on as it has a well-documented halo (Carruba 2016), is separate from the other larger structures of the Vesta and Flora families, is comparatively young, estimated between 200-250 Myr (Spoto 2015), and is numerous, with ~2000 bodies having measured albedos. It therefore served as the ideal testbed to expand upon for more varied C-type families.

The network structure we used are multi-layer perceptrons (MLPs). The input neurons used include the three orbital elements with the metric by Zappala (1990), their standard deviations, and absolute difference in albedo from the parent, h-magnitude, and inverse diameter. The network was kept to 2 hidden-layers and to prevent overfitting. Asteroids associated with the 8 C-type families were labelled with a single neuron output layer as 1, and other background asteroid not within this volume were labelled 0. The final architecture of the network was 9:27:3:1. The models were trained using values from the MP3C database hosted by the Observatoire Côte d’Azur (https://mp3c.oca.eu/). To isolate the family and halo complex, a volume of ±5 standard deviations in the family's centre in proper orbital space was defined. Once the network was trained, the halo asteroids in the box were then introduced as ‘unseen’ data to be evaluated by the network. Additionally, family members were re-introduced as unknown control values. We verified that the network was working as intended by making sure the network was able to correctly categorise known family members.

Our network was able to recover 99.83% of the Erigone family with a predicted certainty of >0.9. 581 asteroids from the halo were predicted by the ANN to be family members, an increase of 32%. The ANNs predictions were pruned manually, where any asteroids with an albedo greater than 0.1 and further than 3 std in (a, e, i) away from the centre were discarded. The experiment was repeated with 5 other C-type families, and large portions of additional asteroids were predicted to be family members: 84 Kilo (+43%), 329 Svea (+42%), 623 Chimaera (+43%), 752 Sulamatis (+25%). These experiments reinforce the notion that asteroid family halos contain a significant number of family asteroids that have been missed for inclusion in the family. We find that ANNs are good complements to the surveying done previously with algorithms such as the Hierarchical Clustering Method (HCM). Additionally, we make the case that they will be useful tools for the expected massive influx of new asteroids that will come with the Vera Rubin Observatory’s LSST.

References:

V. Carruba, S. Aljbaae, O. C. Winter, On the Erigone family and the z2 secular resonance, Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society, Volume 455, Issue 3, 21 January 2016, Pages 2279–2288, https://doi.org/10.1093/mnras/stv2430

Spoto, F., Milani, A., Knežević, Z., 2015. Asteroid family ages. Icarus 257, 275–289. URL: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.icarus.2015.04.041, doi:10.1016/j.icarus.2015.04.041

Zappala, Vincenzo & Cellino, Alberto & Farinella, Paolo & Knezevic, Zoran. (1990). Asteroid families. I. Identification by hierarchical clustering and reliability assessment. The Astronomical Journal. 100. 2030-2046. 10.1086/115658.

How to cite: Marshall-Lee, A., Christou, A., Sivitilli, A., and Humpage, A.: Predicting the origins of C-type family halo asteroids using ANNs , EPSC-DPS Joint Meeting 2025, Helsinki, Finland, 7–13 Sep 2025, EPSC-DPS2025-1603, https://doi.org/10.5194/epsc-dps2025-1603, 2025.

Abstract

The field of Space Situational Awareness (SSA) has become increasingly important in recent years due to the rapid rise in active satellites and the accumulation of space debris in Earth orbit. Accurate orbit determination (OD) and, more importantly, reliable estimates of uncertainty are essential for planning collision avoidance manoeuvres and preserving a safe orbital environment. Over time, machine learning (ML) has also seen increasing use in this area, as its algorithms hold the potential to improve classical OD methods by leveraging measurement data.

Scorsoglio et al. (2023) demonstrated that a specialized type of neural network, known as a Physics-Informed Extreme Learning Machine (PIELM), can perform rapid orbit determination without requiring an initial guess of the state vector. By incorporating the governing differential equations, PIELMs reduce the “black box” nature typically associated with standard neural networks. However, estimating realistic prediction uncertainties remains an open challenge for nonlinear systems, particularly in contexts where Bayesian approaches cannot be directly applied.

In this study, we investigate and compare uncertainty quantification methods in orbit determination by analysing the behaviour of the covariance matrix across different estimation frameworks. Specifically, we examine the classical covariance propagation using the state transition matrix as used in the weighted least squares (WLS) method, a Monte Carlo simulation-based approach employing a standard orbital propagator, and strategies to assess the uncertainty associated with OD results obtained via a PIELM. The comparative analysis aims to assess the fidelity and characteristics of uncertainty estimates produced by each method. All computations are carried out within the AI4POD (Artificial Intelligence for Precise Orbit Determination) framework.

Acknowledgements

The project Artificial Intelligence for Precise Orbit Determination (AI4POD) is funded by Deutsches Zentrum für Luft- und Raumfahrt, Bonn-Oberkassel, under grant 50LZ2308.

References

[1] Montenbruck, Oliver, und Eberhard Gill. Satellite Orbits. Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer Berlin Heidelberg, 2000. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-642-58351-3.

[2] Scorsoglio, A., Ghilardi, L. & Furfaro, R. A Physic-Informed Neural Network Approach to Orbit Determination. J Astronaut Sci 70, 25 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40295-023-00392-w

[3] Liu, Xu, Wen Yao, Wei Peng, und Weien Zhou. „Bayesian Physics-Informed Extreme Learning Machine for Forward and Inverse PDE Problems with Noisy Data“. Neurocomputing 549 (September 2023): 126425. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neucom.2023.126425.

[4] Aigner, B., Dallinger, F., Andert, T., and Pätzold, M.: Integrating Machine Learning algorithms into Orbit Determination: The AI4POD Framework, Europlanet Science Congress 2024, Berlin, Germany, 8–13 Sep 2024, EPSC2024-521, https://doi.org/10.5194/epsc2024-521, 2024.

[5] Dallinger, F., Aigner, B., Andert, T., and Pätzold, M.: Physics Informed Neural Networks as addition to classical Precise Orbit Determination, Europlanet Science Congress 2024, Berlin, Germany, 8–13 Sep 2024, EPSC2024-514, https://doi.org/10.5194/epsc2024-514, 2024.

How to cite: Aigner, B., Dallinger, F., Andert, T., Haser, B., Pätzold, M., and Hahn, M.: Uncertainty Estimation in Orbit Determination: A Comparison of Machine Learning, Monte Carlo and Least Squares Approaches, EPSC-DPS Joint Meeting 2025, Helsinki, Finland, 7–13 Sep 2025, EPSC-DPS2025-706, https://doi.org/10.5194/epsc-dps2025-706, 2025.

Please decide on your access

Please use the buttons below to download the supplementary material or to visit the external website where the presentation is linked. Regarding the external link, please note that Copernicus Meetings cannot accept any liability for the content and the website you will visit.

Forward to presentation link

You are going to open an external link to the presentation as indicated by the authors. Copernicus Meetings cannot accept any liability for the content and the website you will visit.

We are sorry, but presentations are only available for users who registered for the conference. Thank you.

The Transiting Exoplanet Survey Satellite (TESS) is a NASA mission focused on exploring and finding exoplanets around nearby stars using the transiting method. The TESS telescope covers a large field of view of 96 sq. deg in a single exposure. It has four cameras arranged vertically pointing from the ecliptic plane toward the poles. During its first two years of observations, TESS saved full-frame images (FFI) with a 30-minute cadence during about 27 days covering one celestial hemisphere per year.

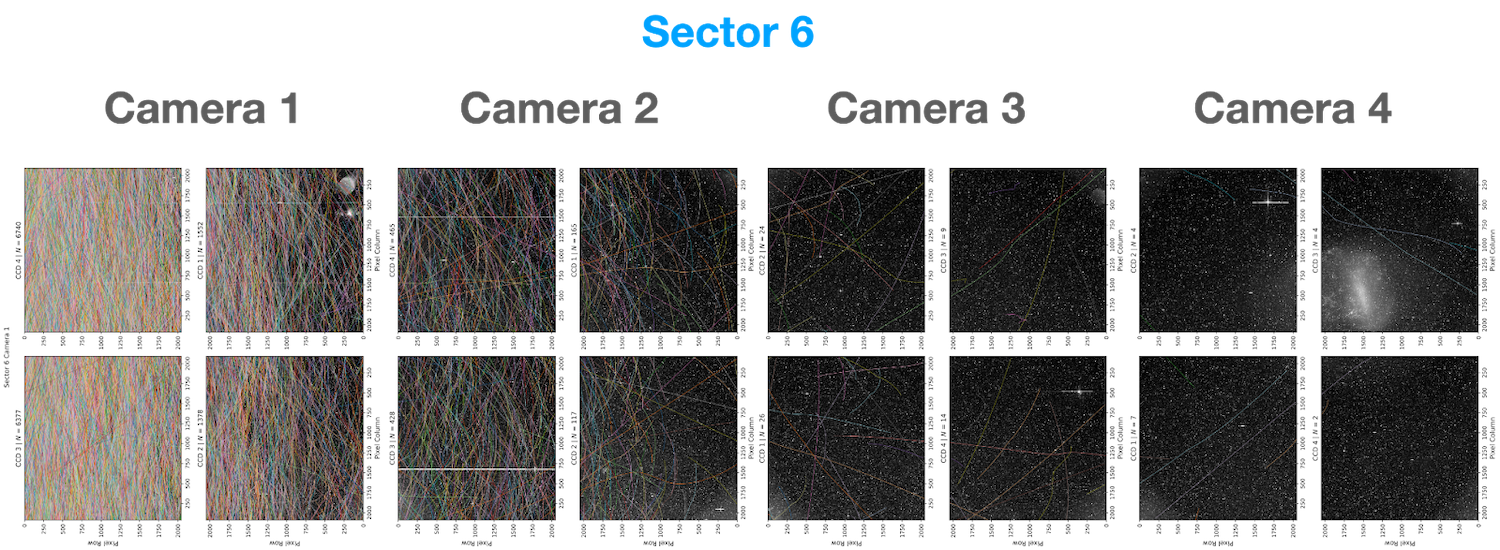

Thanks to this configuration and observing schedule, TESS is able to observe asteroids with a high duty cycle (see Figure 1 for an example of observed asteroid projected tracks in a typical TESS field). Current techniques to search for asteroid signals on images rely on the shift-and-stack method, which relies on testing all possible combinations of directions and speeds an object can move across the image to maximize the detection signal and find the asteroid’s track. This method is computationally expensive, and only attainable when the parameter space (direction-velocity) is constrained, usually to the most common direction of motion(e.g. orbits parallel to the ecliptic plane) and common speeds (e.g. main belt asteroids). This introduces a bias against fast-moving asteroids and high-inclination orbits (projected tracks perpendicular to the eclliptic plane).

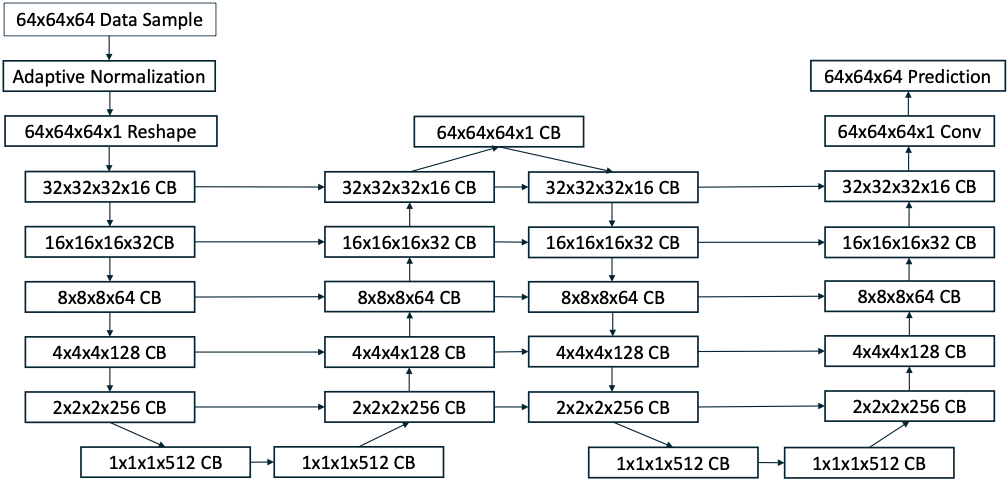

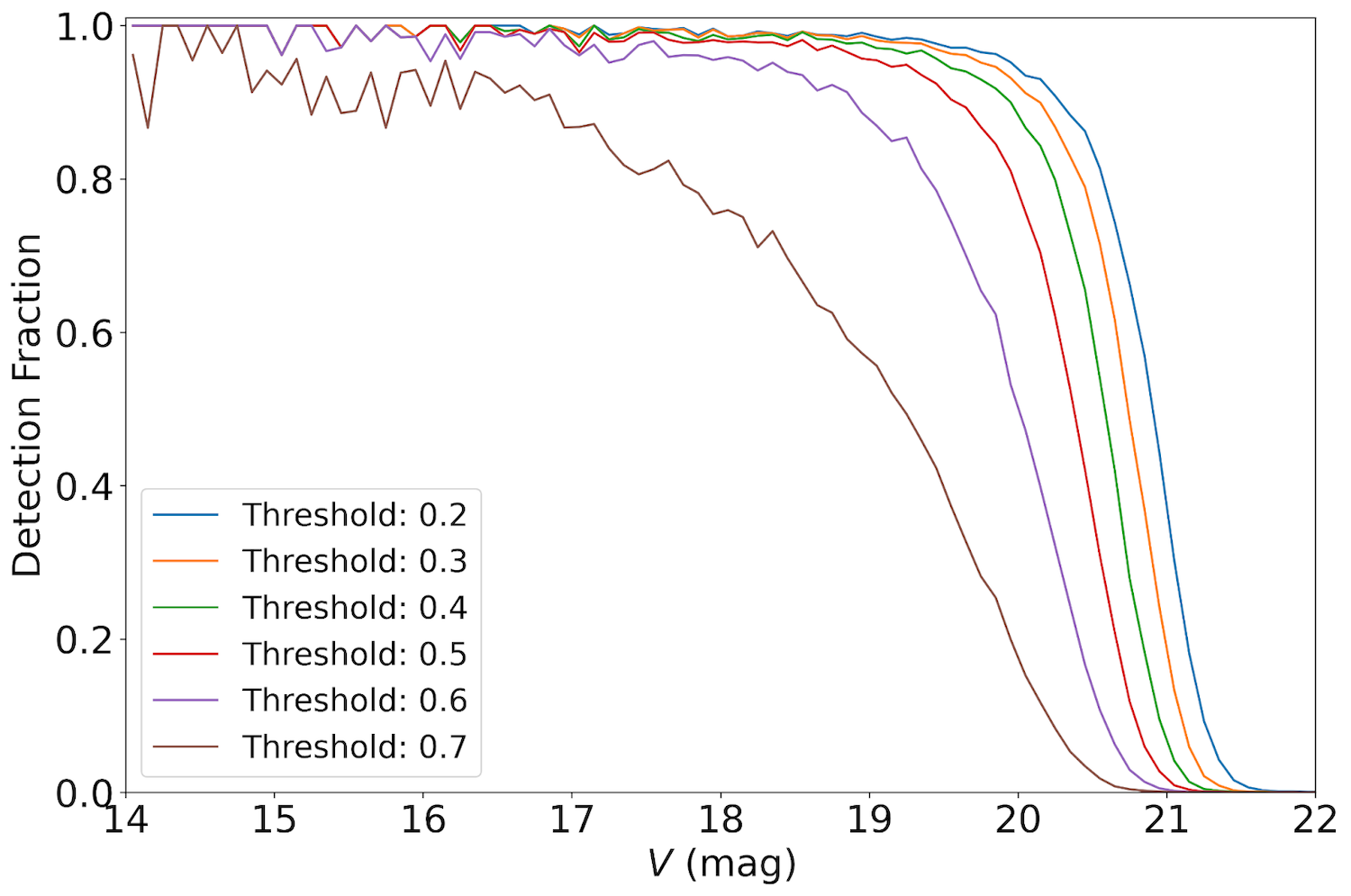

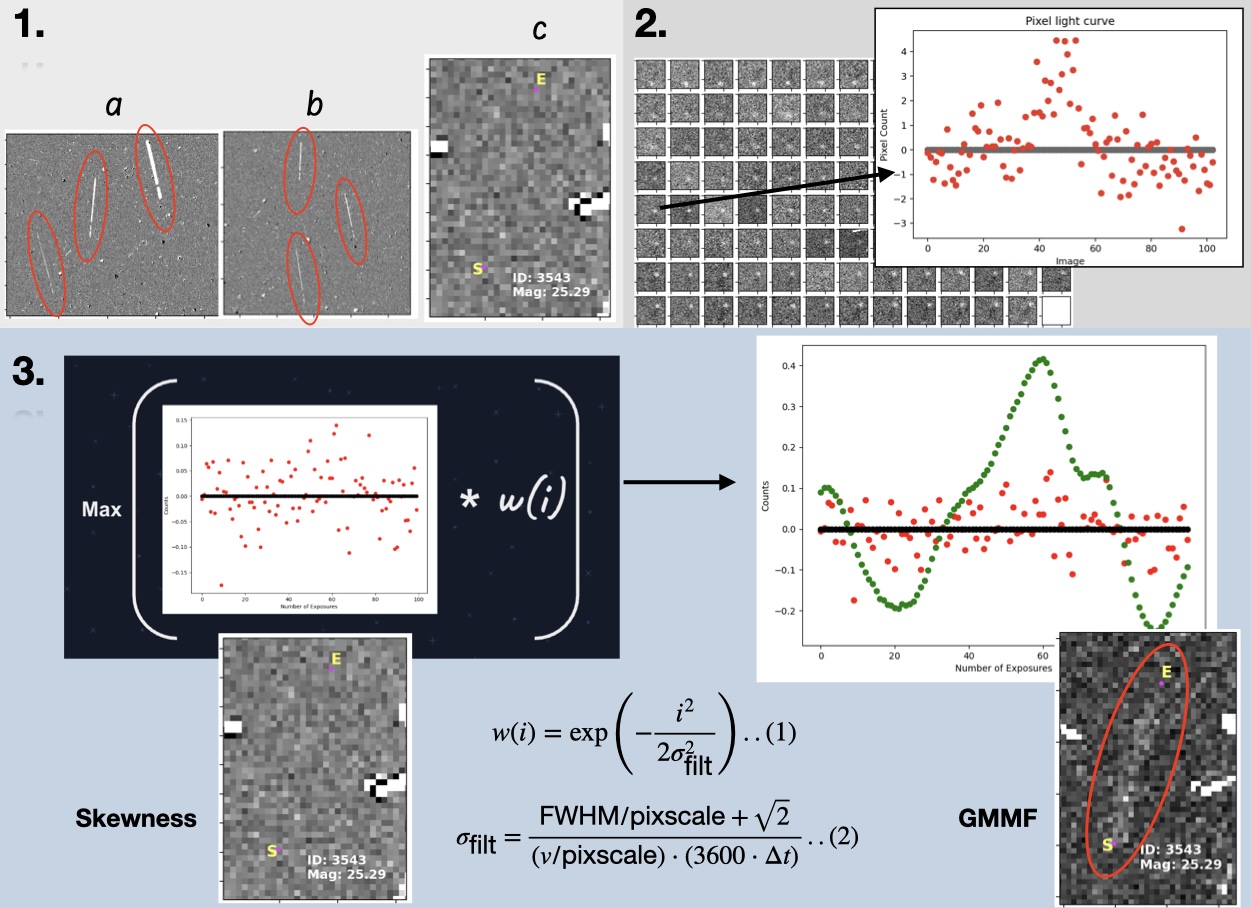

To solve this, we implemented a rotationally invariant neural network (NN) model that performs semantic segmentation to find moving objects in TESS FFIs. This NN has an architecture that uses a W-Net architecture (two 3D U-Nets stacked) with skip connections that output a 3D segmentation mask with asteroid detections. Figure 2 shows details of the W-Net architecture. We constructed a custom training set using 64x64x64 cubes of pixel flux time series and truth masks with the tracks of known asteroids from the JPL Horizon Ephemeris system. During training, these cubes are randomly rotated and flipped to enforce rotational invariance. Our NN model can find known and new asteroids with all kinds of track orientations, showing no bias against objects moving at high inclination orbits, or fast-moving asteroids, or tracks with a change in direction. Figure 3 shows that our NN model detects ~90% of known asteroids down to apparent visual magnitude 20th and has a detection limiting magnitude of ~21. This is on par with current implementations of the shift-and-stack method but without the bias introduced by limiting the range of track direction and velocity.

This machine learning model present an orthogonal method to search for peculiar solar system objects, such as Trans Neptunian Objects or Near Earth Objects, and provides a complimentary approach to current methods. Additionally, is directly applicable to other all-sky survey like observations, such as the Galactic Bulge Time Domain Survey of the upcoming Roman Space Telescope.

In this talk, we will introduce the NN mode, training set construction and details,l and present results from predictions using years 1 and 2 of TESS data. Additionally, we will show preliminary light curves extracted from new asteroids detected by our model.

Figure 1: TESS Sector 6 FFIs with known observed asteroids brighter than V<22, tracks were obtained from the JPL Horizon system. TESS has 4 cameras with 4 CCD each stacked vertically with respect to the ecliptic plane (left) and the celestial pole (right).

Figure 2: W-Net architecture of the neural network model used to identify moving objects in TESS FFI cubes. The network as an Adaptive Normalization layer particularly developed for this data, inputs flux cubes of size 64, and outputs an asteroid prediction probability cube of the same shape.

Figure 3: Asteroid detection fraction as a function of object brightness for multiple predicted probability thresholds. Lower thresholds improves detection fraction reaching 90% at magnitude V=20 for a threshold value of 0.5.

How to cite: Martinez Palomera, J., Powell, B., Tuson, A., and Hedges, C.: AI-enabled Asteroid detection in TESS data , EPSC-DPS Joint Meeting 2025, Helsinki, Finland, 7–13 Sep 2025, EPSC-DPS2025-64, https://doi.org/10.5194/epsc-dps2025-64, 2025.

Active asteroids—hybrid objects that exhibit characteristics of both asteroids and comets—provide unique insights into solar system evolution and the current distribution of volatiles. However, their apparent rarity (~60 known), coupled with the petabyte-sized haystacks of archival survey data in which they may be hidden, makes detections challenging. This work explores the application of machine learning to constrain populations of active small bodies by increasing the rate of data evaluation. Specifically, we employ convolutional neural networks (CNNs) for object detection and classification, tailored to mirror the workflow of Citizen Scientist volunteers who classify objects of interest from thumbnails of archival data.

Trained on a dataset of labeled active small bodies and a large control set of inactive objects, our CNN evaluates image cutouts centered on known small bodies and classifies them based on signs of activity, such as tails or comae. We explore training datasets from both the Canada-France-Hawaii Telescope (CFHT) MegaCam and Subaru Hyper Suprime-Cam (HSC) archives, highlighting the adaptability of the CNN to be retrained and applied to different survey datasets. Our work also evaluates the influence of activity rate among training data in comparison to the predicted activity rate among Main Belt asteroids (1:10,000) and includes a robust response to erroneous thumbnail images.

We find that the CNN demonstrates high precision and recall across both CFHT and HSC archives and present our first results of the CNN’s high-confidence detections, whether previously known or not. This work illustrates the potential of machine learning techniques to accelerate discoveries of active small bodies and is intentionally designed to be used alongside proven Citizen Science applications. Combining AI with by-eye evaluation gives us a powerful and versatile tool in the doorway to next-generation surveys like LSST.

How to cite: Farrell, K. and Trujillo, C.: Needles in a Haystack: Harnessing Machine Learning and Citizen Science to Catch Small Body Activity in Action, EPSC-DPS Joint Meeting 2025, Helsinki, Finland, 7–13 Sep 2025, EPSC-DPS2025-1392, https://doi.org/10.5194/epsc-dps2025-1392, 2025.

The trans-Neptunian region represents a critical window into the early stages of our solar system’s formation, offering a unique opportunity to study the remnants of the planetesimals that contributed to the creation of the planets. The Deep Ecliptic Exploration Project (DEEP), a multi-year survey utilizing the Dark Energy Camera (DECam) on the 4-meter Cerro Tololo Inter-American Observatory (CTIO) Blanco telescope, has been instrumental in characterizing the faint Trans-Neptunian Objects (TNOs) population. This project has determined the size and shape distribution of TNOs, studied their physical properties in relation to their dynamical class and size, and tracked objects over multiple years to gain insights into their orbits. Using a shift-and-stack moving object detection algorithm, the DEEP survey successfully recovered over 110 new objects. While this method has been successful, it relies on computationally expensive velocity assumptions and traditional image stacking techniques. In this work, we introduce an innovative AI-based moving object detection method that offers a fresh perspective on TNO detection, providing a faster, more efficient, and robust alternative to traditional methods.

We introduce a new approach for detecting moving objects in astronomical images, called You Only Stack Once (YOSO). This method simplifies the traditional object detection technique by eliminating the need to account for the velocity vector of each object. Instead of shifting individual images to align with a presumed motion before stacking, YOSO simply stacks a sequence of time-series images without applying directional shifts. As a result, moving sources appear as linear or slightly curved trails, depending on their apparent motion during the observation. These trails are then identified using a machine learning model trained to recognize similar distinct shape and intensity profiles. This approach allows for fast, reliable detection of a wide range of moving objects, from fast Near-Earth Objects (NEOs) to the slower, fainter bodies in the Kuiper Belt.

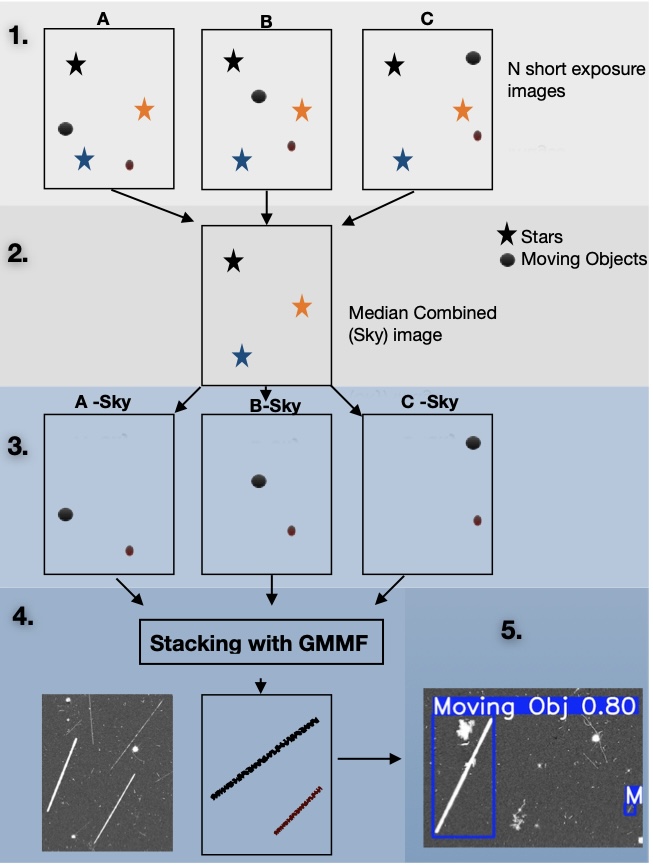

YOSO starts with a series of short-exposure images of the same sky region, typically acquired over the course of a night. After standard preprocessing (see Steps 2 and 3 in Figure 1), the images are stacked to boost the signal of any moving sources. In early versions of the pipeline, we used pixel-wise statistical measures such as mean, skewness, and kurtosis to combine the frames, but these proved limited in their ability to enhance faint sources. To improve sensitivity, we developed the Gaussian Motion Matched Filter (GMMF), a new statistics, tailored to detect the footprint of a moving object on a single pixel. Unlike conventional Gaussian smoothing, GMMF applies a Gaussian-weighted convolution along the temporal axis of each pixel stack, matching the expected motion profile of moving sources as shown in section 2 in Figure 2. GMMF can reliably detect sources with signal-to-noise ratios as low as 0.5:1.0, all without the need for a brute-force search over velocity space. The details of this filter have been shown in Figure 2.

Once potential trails have been generated, we use a deep learning model to identify and classify them. Our detection network is based on YOLOv8L, a high-performing convolutional neural network (CNN) architecture that has been pretrained on a broad set of visual data. YOLOv8L is particularly well-suited to this task because it generalizes effectively even with limited domain-specific training data, learns quickly, and handles noisy or low-contrast features robustly. For our use case, we retrained the model on a synthetic dataset designed to mimic real astronomical trails, including low SNR signals, linear trajectories, and varying brightness levels.

YOSO is a highly adaptable framework designed to optimize the detection of moving objects across a broad spectrum of telescopes, observational datasets, and populations, from Kuiper Belt Objects (KBOs) to fast-moving Near-Earth Objects (NEOs). Unlike shift-and-stack techniques that produce compact point sources, often vulnerable to false positives from random noise or disjointed detections due to tiling strategies, YOSO leverages the naturally occurring, spatially correlated trails left by moving sources. These extended structures are particularly well-suited for detection via machine learning models, which excel at identifying such coherent patterns.

A key advantage of YOSO is its ability to significantly suppress false positives. The deep learning model is trained to recognize elongated, linear features, enabling it to discriminate real object trails from stochastic noise or unrelated pixel artifacts. Whereas traditional surveys often require stringent signal-to-noise thresholds (e.g., above 5σ) to maintain reliability, YOSO is capable of operating at lower thresholds down to 4σ by combining statistical image stacking with deep learning-based confidence assessments. Once a candidate trail is identified, the model outputs a bounding box around the detection (as illustrated in Step 5 of Figure 1), which can then be used to extract the trail and estimate its apparent motion and direction.

The primary goal of this method is to achieve near real-time detection of moving objects as observational data becomes available. This presentation will outline the core methodologies behind the YOSO framework and highlight key challenges encountered during its development, particularly emphasizing the role of the trail-based search in enabling fast and effective detection of trans-Neptunian objects. I will also discuss its potential application to LSST deep drilling fields and other wide-field surveys, where it may significantly improve the discovery rate of Solar System objects, especially those with sky motions that are not well-suited to traditional deep drilling strategies.

Figure 1: The illustration of the YOSO pipeline, the process has been applied to 103 time series of observations of Kuiper Belt Object search (120 sec exposure each image).

Figure 2: Schematic illustrating the Gaussian Motion Matched Filter (GMMF) process applied to 103 time series of observations of Kuiper Belt Object search (120 sec exposure each image).

How to cite: Pandey, N.: You Only Stack Once (YOSO): Fast TNO Detection via Gaussian Motion Matched Filtering and Deep Learning, EPSC-DPS Joint Meeting 2025, Helsinki, Finland, 7–13 Sep 2025, EPSC-DPS2025-961, https://doi.org/10.5194/epsc-dps2025-961, 2025.

Until recently, permanently shadowed regions (PSRs) on the Moon were devoid of high-resolution high-signal-to-noise imaging. ShadowCam, the NASA-funded instrument onboard the Korea Aerospace Research Institute (KARI) Korea Pathfinder Lunar Orbiter (KPLO) satellite brings 200x more sensitive images with 1.7 m per pixel resolution.

ShadowCam’s growing and publicly available dataset contains millions of previously unknown impact craters that provide important insight into various physical processes such as the impact gardening, volatile excavation, or mass wasting in lunar PSRs. In this presentation, we describe our crater detection techniques and the current state of our crater detection efforts on the ShadowCam image dataset.

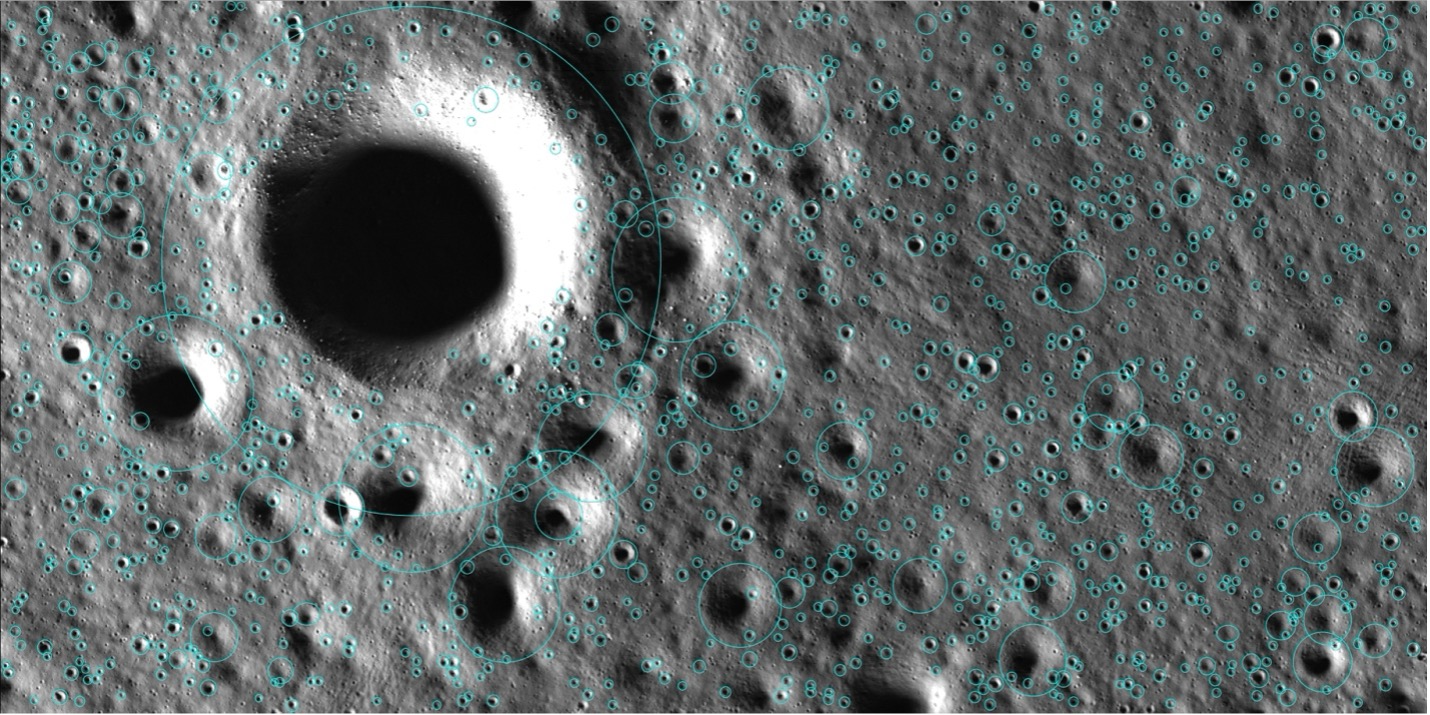

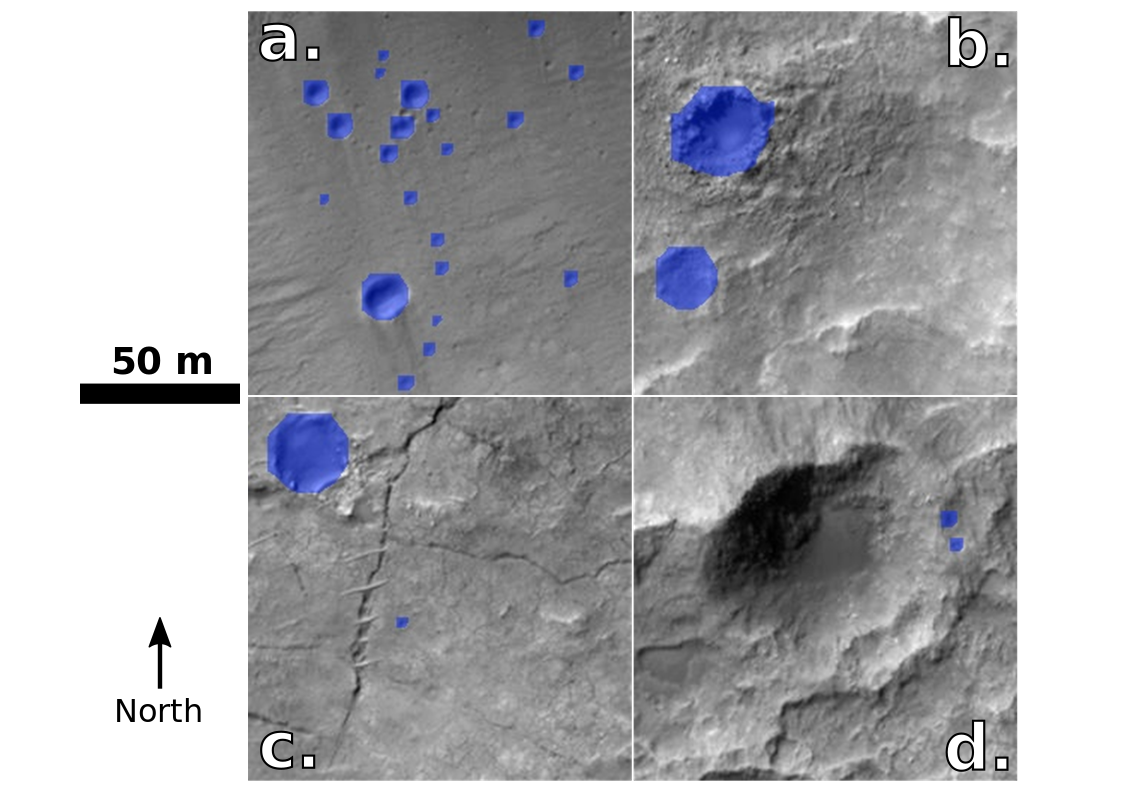

With the advent of machine learning, we can now efficiently process the high-resolution lunar images. Machine learning crater detections have been successfully applied on numerous planetary bodies, e.g. the Moon [1,2,3], Mars [4,5], and Ceres [6,7]. In our work, we use the YOLOv8 (You-only-look-once) object detection framework designed to provide high speed and accuracy for detection of various objects in images [8]. To minimize the complexity of our object detection model, we limit to only one class: “crater”, where all other features on each image are considered a part of the background. The architecture of our neural network is based on the YOLOv8m model with 25.9 million parameters with the default resolution of our detection model of 512x512 pixels. The detection model was trained using 5240 impact craters from various LROC-NAC images. The training dataset of our model was enhanced by employing several image augmentations such as rotation, contrast and brightness variations provided by the albumentations library to increase the robustness of our crater detection algorithm (CDA).

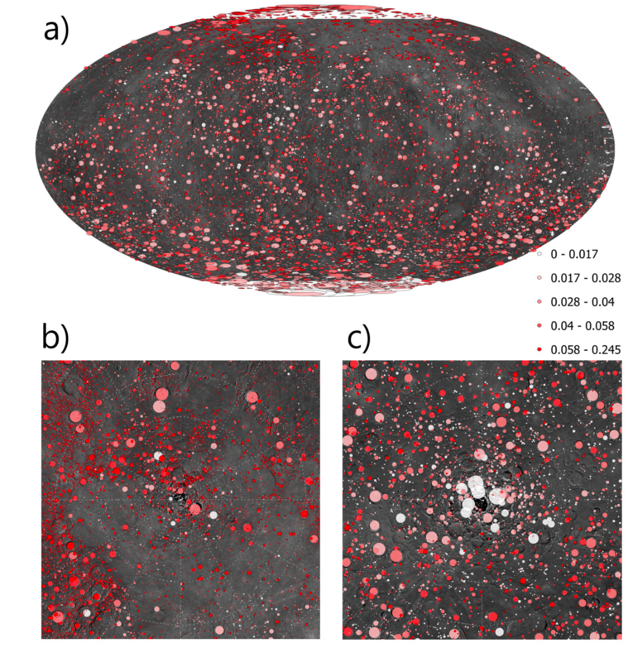

The ShadowCam images used for crater detection were orthorectified and geolocated by the ShadowCam team. These images have various sizes reaching up to 100,000 pixels in the x or y dimension. To efficiently accommodate images of different sizes we slice each image into tiles with 50% overlap. To detect craters of various sizes, we use 6 different image slice sizes: 256x256, 512x512, 1024x1024, 2048x2048, 4096x4096, and 8192x8192 pixels, where all these slices are rescaled to 512x512 pixels before our CDA is applied. To remove duplicate detections, we apply the non-maximum suppression algorithm (NMS) with the Intersection over Union (IoU) metric, where the IoU threshold is set to 0.3. NMS ensures that only detections with the highest confidence values are kept, and the IoU threshold allows us to keep nested impact craters. Ultimately, the CDA results in geolocated bounding boxes and confidence values for each detected impact crater (Figure 1).

We deployed our ML-based CDA on 22,256 images from the PDS ShadowCam dataset, which corresponds to 2.2 TB of image data covering approximately 5.3 million km2 of the lunar surface. The processing time for the entire dataset was approximately 3000 GPU hours on a Nvidia A100 GPU. In this dataset, we find 1,013,440,231 impact craters larger than 16 meters in diameter (8 pixels or larger). The average detection time per crater is approximately 0.3 microseconds, which is 6 orders of magnitude faster than human crater detections [9]. The images in the ShadowCam dataset overlap spatially, and therefore many craters are detected multiple times at different times and illumination conditions.

We tested the performance of our ML-based CDA on a dataset of 50,000 craters selected from different ShadowCam images and vetted by four human researchers. We find that our CDA has a true positive detection rate of 98.2 and that 1.8% are false positive detections for craters with diameters between 16 meters and 4 km. Additionally, ~1% of impact craters are not detected by our CDA. Smaller craters are also detected by our CDA, but the detection confidence values are lower and the consensus of the true/false detection varies significantly between different researchers for these small craters. Larger craters (>1 km in diameter) are already contained in the Robbins 2019 global crater database [10] and are therefore not the target of our analysis.

Our detection method will be applied to all future ShadowCam images as well as higher level data products such as controlled mosaics. We will also improve the ability of our detection algorithm to perform better for: impact craters in low-SNR regions, degraded craters, and morphologically complex craters. We are also planning to conduct a large-scale impact crater detection vetting with the help of citizen scientists. Ultimately, we will train a lightweight version of our detection algorithm for real-time detection of impact craters on a wider range of devices (e.g., web browsers, etc.)

Acknowledgments: We thank the KPLO and ShadowCam operations and science teams for acquiring the ShadowCam dataset. ShadowCam PDS https://pds.shadowcam.asu.edu/ was used in this work. PP was supported by the NASA Planetary Science Division Research Program through the GSFC Planetary Geodesy ISFM and the award number 80GSFC24M0006.

|

Figure 1. A ShadowCam full-resolution segment of the Faustini crater located at (x = 82.0 1.4 km, y = 5.0 0.7 km). This image contains 1164 impact craters with diameters from 16 m to 1.2 km. While our crater detection algorithm provides bounding boxes for each crater, we display each detection as an ellipse with the rotation angle equal to zero for better clarity. We find 98.2% of our detections are true positives, while 1.8% are false detections. Additionally, ~1% of craters remained undetected. Note, that craters with bounding boxes extending outside this image are not displayed but are still detected by our CDA. |

References: [1] Benedix G. K et al. (2020) Earth and Space Science, 7, 3, e01005, [2] Fairweather J. H et al. (2023) Earth and Space Science, 10, 7, e2023EA002865, [3] La Grassa R. et al. (2023) Remote Sensing, 15, 5 1171, [4] Lagain et al. (2021) Nature Communications, 12, 6352, [5] Lagain et al. (2022) Nature Communications, 13, 3782, [6] Latorre F. et al. (2023) Icarus, 394, 115434, [7] Herrera C. et al. (2024) Astronomy & Astrophysics, 688, A176, [8] Jocher G. et al. (2023) https://github.com/ultralytics/ultralytics, [9] Robbins S. J. et al. (2014) Icarus, 234, 109-131,[10] Robbins S. J. (2019) Journal of Geophysical Research: Planets, 124, 4 871-892

How to cite: Pokorny, P., Mazarico, E. M., Robinson, M. S., Mahanti, P., and Willaims, J.-P.: Machine Learning Driven Detection of 1 Billion+ Lunar Impact Craters in Permanently Shadowed Regions Using ShadowCam Data, EPSC-DPS Joint Meeting 2025, Helsinki, Finland, 7–13 Sep 2025, EPSC-DPS2025-469, https://doi.org/10.5194/epsc-dps2025-469, 2025.

Recent advancements in artificial intelligence (AI) have opened new horizons for space exploration, especially in astrometry. In this work, we developed a deep learning-based algorithm to detect and classify bright sources—namely stars, satellites, and cosmic rays—in the Cassini Imaging Science Subsystem (ISS) images of the Saturn system. This novel approach leverages the precision of deep neural networks to process over 13,000 images, 1024×1024 pixels and with an exposure time <1 second, forming a robust dataset for training.

To generate labeled data without manual intervention, we designed a custom source detection algorithm using classical image processing techniques, such as mathematical morphology. Detected sources were then matched with star catalogs and ephemerides of Saturn’s moons to label stars and satellites; unmatched sources were classified as cosmic rays. The resulting dataset was used to train a YOLO (You Only Look Once) model—the state-of-the-art framework for detection and classification of objects on images and videos, that gained its popularity for its speed and accuracy.

The network achieved strong classification results: cosmic rays were identified with 90% average precision and no false positives. Satellites were accurately classified 83% of the time, while stars proved more challenging due to their variability, achieving a 54% classification rate with 43% being misclassified as cosmic rays.

Beyond detection, we used the classified data to study cosmic ray behavior in Saturn’s outer magnetosphere (15–100 Rs). Temporal variations were correlated with neutron monitor data from Earth, offering a broader view of cosmic ray activity in the solar system. Furthermore, analysis of the energy and directional characteristics of these particles demonstrates that ISS NAC images can be effectively repurposed for particle science. This AI-driven framework provides a new tool for exploring the Saturn system and could aid in the discovery of previously undetected moons or energetic events.

How to cite: Quaglia, G., Lainey, V., Tochon, G., and Strauss, D. T.: A deep learning based method for the detection and classification of bright sources on Cassini ISS images, EPSC-DPS Joint Meeting 2025, Helsinki, Finland, 7–13 Sep 2025, EPSC-DPS2025-500, https://doi.org/10.5194/epsc-dps2025-500, 2025.

Introduction

Planetary rover camera stereoscopy has evolved within decades to serve engineering and science tasks from on-board navigation over mission and instrument planning to science operations and exploitation based on 3D data [1].

Mastcam-Z [2] is a zoomable multispectral stereoscopic camera on the Mars 2020 Perseverance rover. Its stereo range useful for geologic spatial investigations spans from very close range up until a few dozens of meters, with a quadratically increasing range error [3]. Whilst small deviations of geometric camera calibration from “truth” result in a predictable and correctable systematic error, actual stereo processing introduces 3D range noise in the named quadratically increasing form.

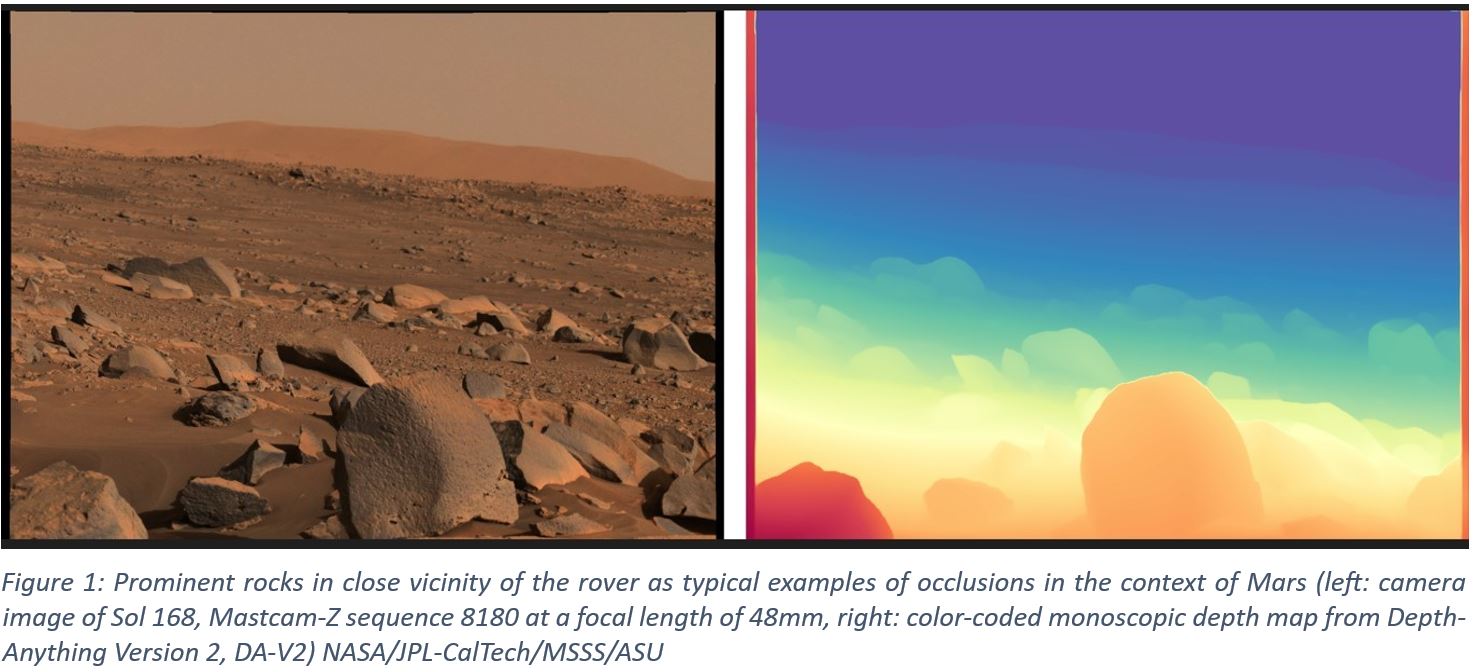

Recently available AI methods show promising solutions determining monoscopic depth (i.e. depth from single images in pixel resolution) [4] for a large range of applications. Such range maps lack true scale, as no artificial objects with known scale can be expected on planetary surfaces. Yet, pixel-resolution occlusion determination and micro-shape are well represented, as shown in Figure 1. This inspired the combination of monoscopic AI-based range determination with true scale as available from calibrated stereoscopy.

AI-Based Enhancement of Stereoscopic Range Products

Monocular depth models such as Depth Anything V2 (DA-V2, a deep learning-based system for estimating depth from a single camera image [4]) have emerged to powerful tools in image simulation, segmentation and scene understanding, however do not provide exact scale. Relative depth estimates produced by such monocular depth estimation need to be turned into physically meaningful metric depth values. Calibrated stereo camera configurations such as Mastcam-Z provide true-scale depth maps. Fusing them works by establishing local correspondences between the two depth maps and fitting range transformation functions that can convert pixel values from the monocular (unscaled) domain into the stereo (scaled for true distances) domain. These transforms are calculated and applied locally, either per pixel or per block of pixels, to account for spatial variations in the relationship between the two depth sources. Edge-aware processing ensures that depth discontinuities are handled more precisely on occlusions (such as rocks or boulders) to select search areas for which transformations are calculated. The result is a scaled depth map that combines the high-frequency detail and spatial completeness of DA-V2 with the geometric accuracy of stereo photogrammetry, enabling detailed yet quantitatively accurate depth maps suitable for scientific analysis and engineering applications, such as planetary rover navigation and terrain modeling.

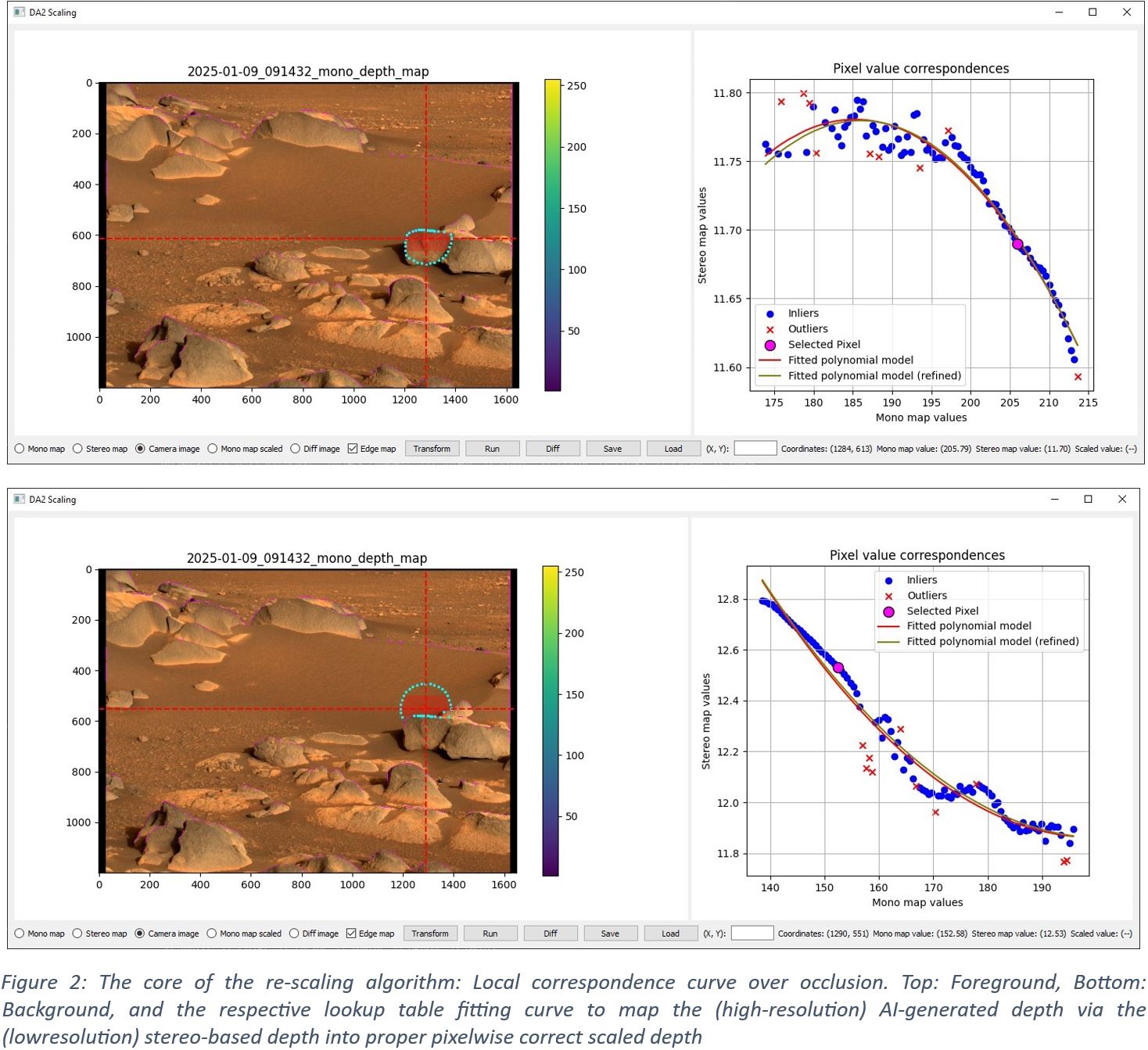

The basic operation of the algorithm is as follows:

- Detect occlusion edges in mono depth map to form a binary "edge map"

- Iterate over mono depth map in blocks of configurable size

- For each mono depth map pixel, create a circular search area using the pixel as its center, taking into account occlusion edges

- Calculate correspondences between mono and stereo map depth values within the search area (Figure 2)

- Fit function to correspondence data using quadratic, polynomial, exponential, or linear approximation

- Transform mono map values in current pixel block to final product using fitted function.

Several enhancements are implemented – most notably a two-step function fitting procedure and per-pixel interpolation of transformations based on spatial distance – as well as more fine-grained options to control the behavior of the algorithm. A prototype version of this scaled DA-V2 algorithm has been integrated into the nominal Mastcam-Z 3D PRoViP vision processing [6].

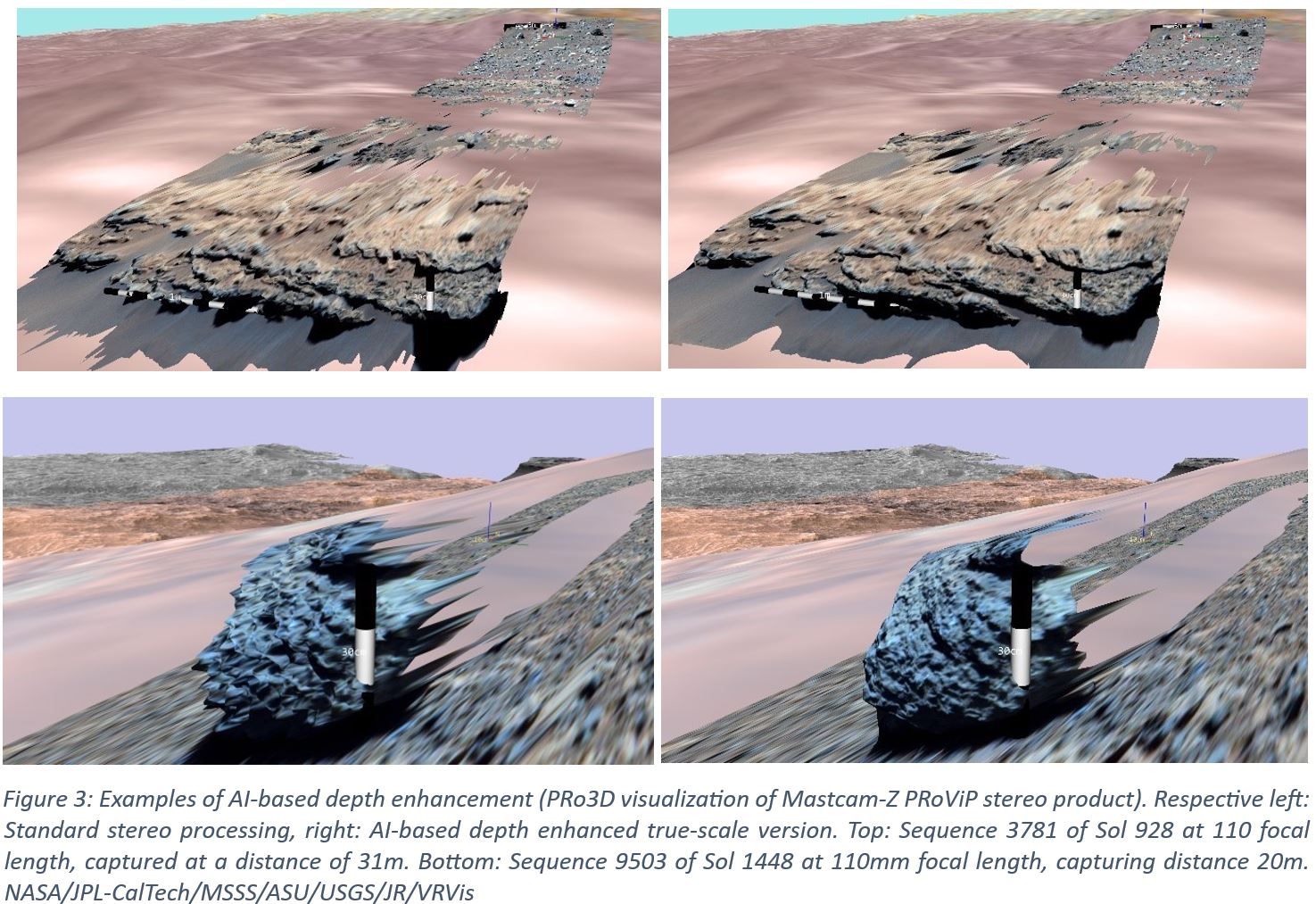

Qualitative Results

A series of preliminary tests indicate highly promising performance, leading to a substantial range extension of the nominal fixed-baseline stereo capabilities of stereoscopic imaging instruments, in particular for the planetary science case. From examples (see Figure 3) it is evident, that at least a range boost of 2 to 5 can be expected by using the described approach.

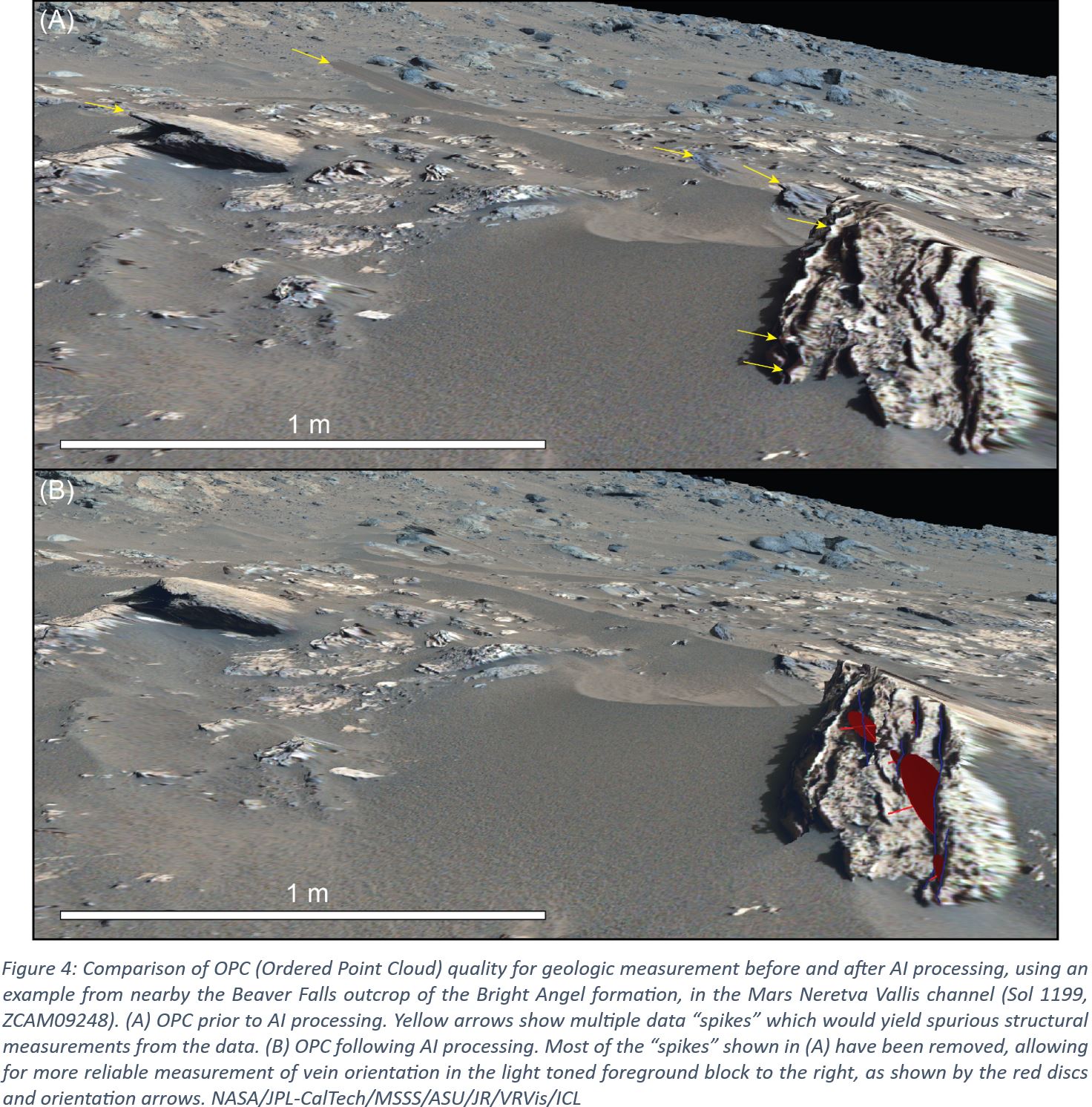

A typical use case to both the original (conventional) stereo-derived 3D result and the AI-enhanced version in comparison (Figure 4) gains the following preliminary assessment:

- Prior to AI processing, the data from this area shows several “spikes” which preclude reliable structural measurements (e.g. strike/dip of veins in the foreground block) being acquired. In the case above (at 34 mm focal length), this occurs at distances of just ~ 6 – 8 m from Mastcam-Z.

- Following AI enhancement, these “spikes” are removed, allowing more reliable measurements of Ca-sulfate vein orientations to be measured.

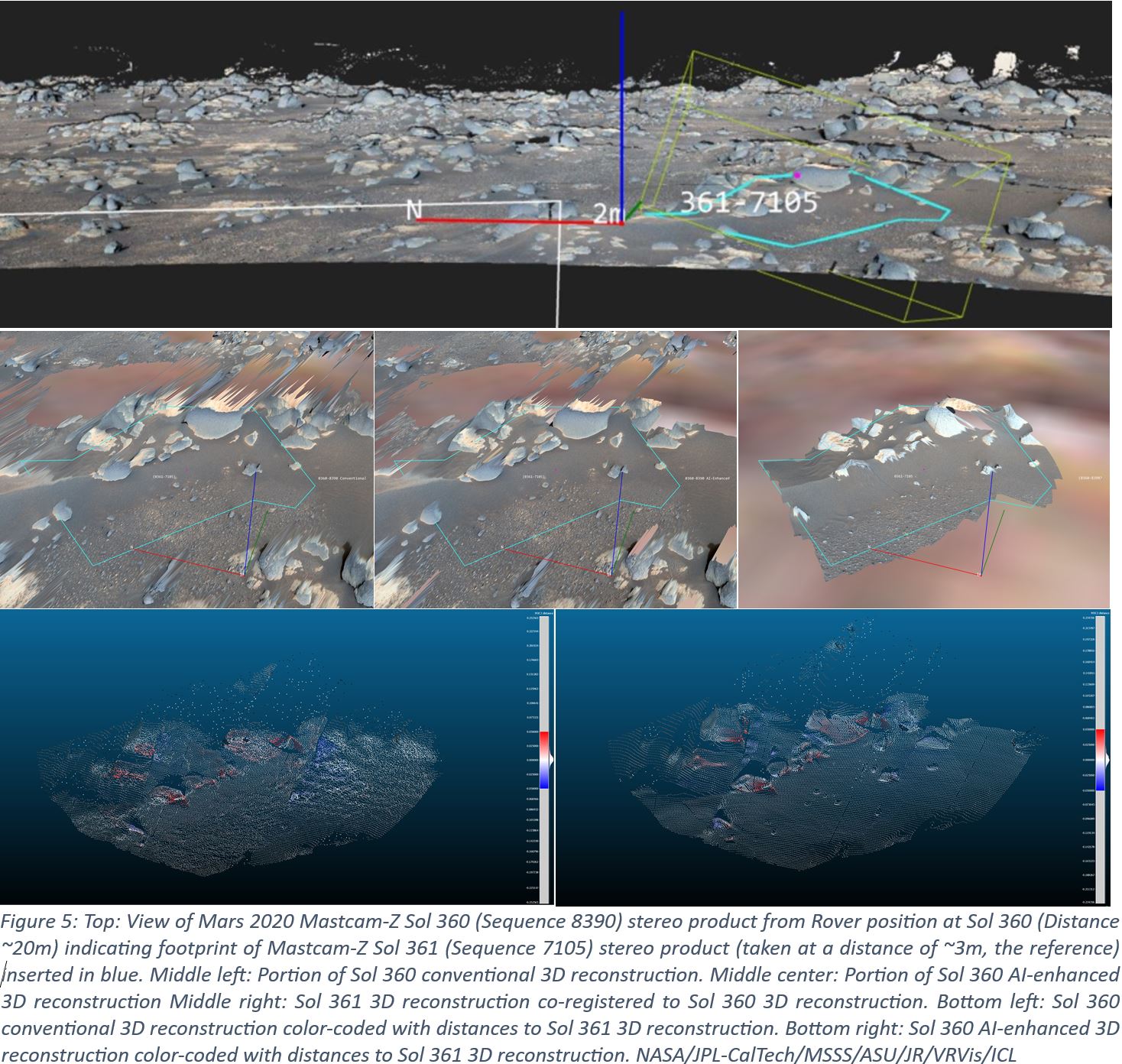

Towards Validation of AI-Based Stereo Enhancement

A highly comprehensible way for a qualitative comparison is to toggle between the surfaces to be compared. This allows to study structural deviations at different viewpoints. Changing into wireframe mode can further enhance the perception of topographic differences.

A series of quantitative validation approaches is under development. These include:

- 3D-comparison between AI-enhanced surface reconstruction using stereo pairs viewed from medium distance, with “conventional” stereo reconstructions of the same scene viewed from close-range (including co-registration to minimize systematic errors from localization and camera calibration) – see Figure 5, top and middle

- Color-coding the reference surface according to the distance to the other one using the distance between surface points by using the up-vector or surface normals (Figure 5, bottom)

- 3D-comparison of AI-enhanced surface reconstructions from images taken with the same imaging geometry under different illumination conditions

- Independent geologic analysis on AI-enhanced and conventional Digital Outcrop Models (DOMs) and results comparison of, e.g., dip-and-strike measurements

- Analysis of shadow shapes with obtained object outlines.

Outlook

A statistically significant validation of the approach is presently in development and planned to be finalized before the joint EPSC/DPS Conference 2025.

A planned improvement of the visual comparison method between surfaces is to show color-coded deviation vectors between vertices. This works best in wireframe mode or with semi-transparent surfaces. Furthermore it should be possible to query numerical deviation values by clicking on a surface point.

Acknowledgement

This work was funded by the ASAP Project AI-Mars-3D (FFG-911920). We thank Komyo Furuya of JR for operational end-to-end implementation and documentation of the re-scaling algorithm.

References

How to cite: Paar, G., Traxler, C., Jones, A., Ortner, T., Bell, J., Gupta, S., and Barnes, R.: AI-Based Extension of Rover Camera Stereo Range – Starting Validation on Mars 2020 Mastcam-Z Geologic Use Cases, EPSC-DPS Joint Meeting 2025, Helsinki, Finland, 7–13 Sep 2025, EPSC-DPS2025-387, https://doi.org/10.5194/epsc-dps2025-387, 2025.

Introduction

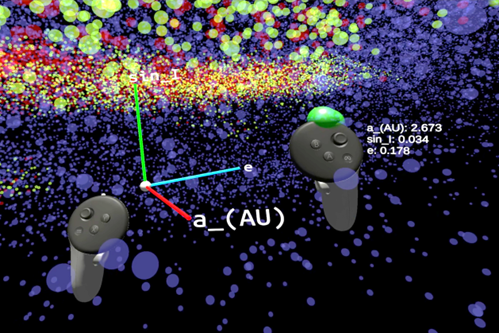

Impact craters are essential markers for reconstructing the geological history of planetary surfaces [1]. On Mars, where no absolute radiometric dating has yet been conducted in-situ, the density of craters remains the main chronometer used for dating surface units [2, 3]. However, this method critically depends on the correct identification of primary craters, as secondary craters (formed by ejecta from a primary impact) and ghost craters (highly degraded

or buried) must be excluded to avoid significant overestimations of surface ages [4]. As the identification of crater morphological features is still a long, repetitive, and subjective task when performed manually, the application of modern computer vision techniques has become more and more relevant. While automated crater detection has seen substantial progress in recent years thanks to deep learning and computer vision techniques [5, 6, 7], the classification of craters based on their morphology remains largely unexplored. Yet, such classification is essential to ensure both the validity of crater inventories and the robustness of derived age estimates.

Dataset and Preprocessing

To train our classifier, we relied on the comprehensive work of Lagain et al. (2021) [4], which provides a manually annotated catalogue of more than 376,000 craters with a size superior at 1km in diameter into four morphological classes: Regular, Secondary, Ghost, and Layered. Image patches centered on each crater are extracted from the global CTX mosaic [8], after reprojection in local stereographic coordinates to preserve the circular geometry of craters at high latitudes. To ensure robustness, we refine the crater locations and sizes using a circle detection algorithm based on the Hough transform [9]. This preprocessing step significantly improves the alignment between craters and image content, a critical requirement for effective supervised learning. In order to train our model, we used 72,000 classified craters, divided in train (28,000 crater), validation (6,000 craters) and test (45,000 craters).

Methodology

We trained a convolutional neural network classifier based on the YOLOv11 architecture, using a balanced and augmented subset of the crater database. Each image patch is resized and normalized, and we apply standard data augmentation strategies including rotations, flips, and artificial masking to simulate realistic artefacts in CTX images. The model outputs is a classification among the four crater classes describe previously. raining was conducted over 40 epochs on a high-performance multi-GPU server using a cross-entropy loss function and a cosine decayed learning rate schedule. Figure1 show the improvement of accuracy through the learning phase on the validation dataset.

Figure1: Validation accuracy with respect to learning epochs

Results

The final model achieves a classification accuracy of over 80% on a geographically diverse and independent test subdataset containing over 45,000 craters. The Figure2 shows the confusion matrix which gaves us a good insight as how the classification model performed. Performance remains consistent across latitudes. Figure3 shows the classification made on 12 example craters, showing excellent classification, including robustness to illumination conditions and image condition (corrupted data).

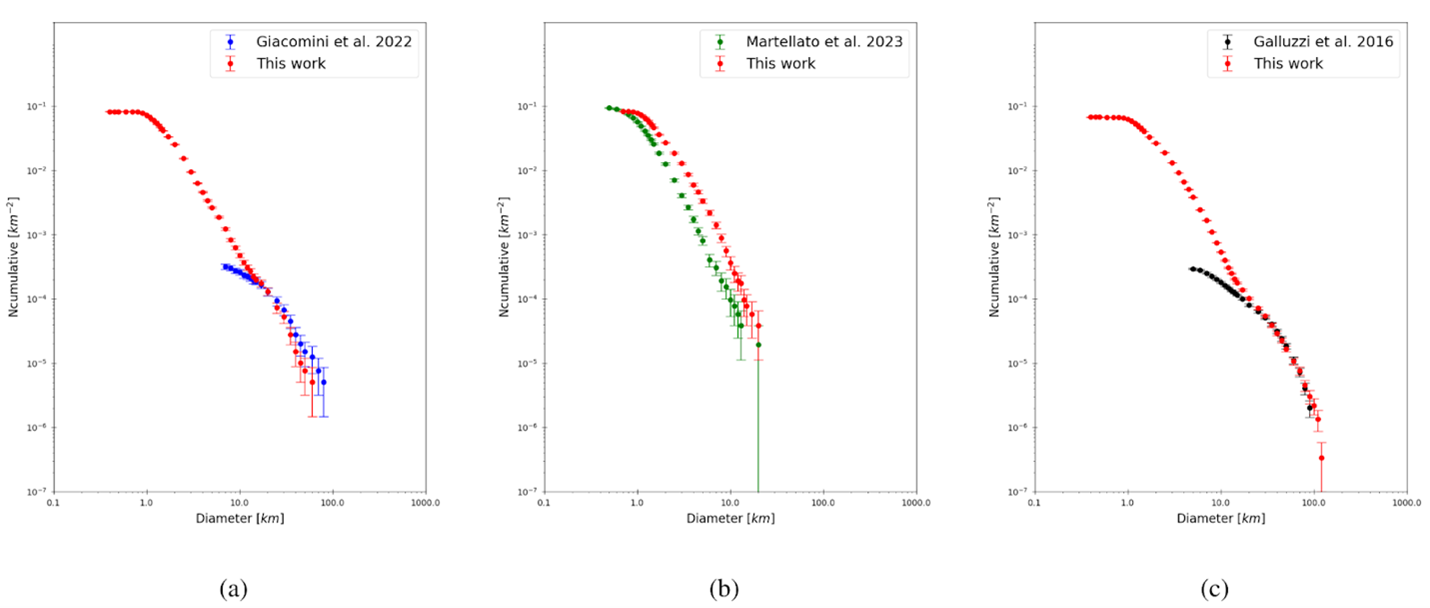

We also demonstrate the practical use of our classification model in the context of surface dating. By comparing cumulative crater size-frequency distributions (CSFD) before and after removing ghost and secondary craters, we show that automated filtering improves the coherence of the inferred ages with those expected from established crater chronologies.

Figure2: Confusion matrix made on the test subdataset. These results show for instance that 80% of true Ghost crater—which represent 2703 craters—where correctly classified, and 2% of them (84 instances) where misclassified as Layered. Overall, the performance is excellent. The regular crater appears slightly more difficult to classify, most probably due to human misclassification.

Figure3: Example of 12 crater present in a test area between -100° and -92°E longitude and 0° to 8°S latitude, which were, from top to bottom, classified as Ghost, Layered and Regular.

Discussion and Conclusion

We present a novel, scalable, and accurate pipeline for automatic crater classification, which complements existing detection models and provides a new tool for planetary surface dating.

This study represents the first fully automated morphological classification of Martian impact craters using deep learning. Our results demonstrate the potential of AI-based approaches to improve crater-based chronostratigraphy, especially when applied systematically to global datasets.

As a future work, we plan to extend the model to the Moon and Mercury using transfer learning, but also incorporate additional crater classes or features (e.g., central peaks, double-layer ejecta). Finally, the plan to refine existing Martian chronologies using the filtered crater populations.

References

[1] W. K. Hartmann, G. Neukum, Cratering chronology and the evolution of

mars, Space Science Reviews 96 (2001) 165–194.

[2] G. Neukum, B. Ivanov, W. Hartmann, Cratering records in the inner solar system in relation to the lunar reference system (2001).

[3] B. A. Ivanov, Mars/moon cratering rate ratio estimates, Chronology and Evolution of Mars 87, 2001.

[4] A. Lagain, S. Bouley, & al., Mars crater and database: A and participative project for the classification of and the morphological characteristics of large martian and craters, The Geological, 2021.

[5] G. K. Benedix, A. Lagain, K. Chai, S. Meka, S. Anderson, C. Norman, P. A. Bland, J. Paxman, M. C. Towner, T. Tan, Deriving surface ages on mars using automated crater counting, 2020.

[6] R. La Grassa, G. Cremonese, I. Gallo, C. Re, E. Martellato, Yololens: A deep learning model based on super-resolution to enhance the crater detection of the planetary surfaces, 2023.

[7] L. Martinez, F. Andrieu, F. Schmidt, H. Talbot, M. S. Bentley, Robust automatic crater detection at all latitudes on mars with deep-learning, 2025.

[8] J. L. Dickson, B. L. Ehlmann, L. Kerber, C. I. Fassett, The global context camera (ctx) mosaic of mars: A product of information-preserving image data processing, 2024.

[9] L. Martinez, F. Andrieu, F. Schmidt, M. S. Bentley, Automatic crater classification using a deep-learning-based pipeline, JGR Machine Learning, under review, 2025.

How to cite: Martinez, L., Andrieu, F., Schmidt, F., and Bentley, M. S.: Automatic classification of Martian impact craters using deep learning: a new tool to improve planetary surface dating, EPSC-DPS Joint Meeting 2025, Helsinki, Finland, 7–13 Sep 2025, EPSC-DPS2025-294, https://doi.org/10.5194/epsc-dps2025-294, 2025.

Please decide on your access

Please use the buttons below to download the supplementary material or to visit the external website where the presentation is linked. Regarding the external link, please note that Copernicus Meetings cannot accept any liability for the content and the website you will visit.

Forward to presentation link

You are going to open an external link to the presentation as indicated by the authors. Copernicus Meetings cannot accept any liability for the content and the website you will visit.

We are sorry, but presentations are only available for users who registered for the conference. Thank you.

Introduction

Artificial Intelligence (AI) is one of the most influential fields of the 21st century (Zhang et al., 2021). Rich, E (2019) candidly described it as “the study of how to make computers do things which, at the moment, people do better”, today AI often surpasses human ability in tasks like large-scale data mining and pattern recognition - its true strength. AI’s subfields - Machine Learning (ML) and deep learning (DL), play a critical role in expanding the usage to a vast variety of fields like planetary science, astronomy, earth observations, and remote sensing, just to name a few. There is an expected inclination towards incorporating AI more frequently in the studies of planetary science given the vast and complex nature of planetary data. In fact, AI has already been instrumental in extracting meaningful insights and advancing research in both interplanetary and astronomical studies.

In planetary sciences, several AI techniques have been employed in order to bridge gaps in our understanding of the varied patterns and occurrences for studying the natural features observable from the data returned by scientific payloads. For example, PCA and cluster analysis can help in detecting patterns of compositional variation from multi and hyper-spectral imagery (Moussaoui et al., 2008; D’Amore & Padovan, 2022). Furthermore, to study specific features and patterns in their occurrences, correlations with neighbouring features; unsupervised algorithms and more complex -supervised techniques can be helpful depending on the scale of the task.

From simple methods of unsupervised learning like clustering used to study the spectral signatures of Jezero crater on Mars (Pletl et al., 2023) to applying large language models to track asteroids affected by gravitational effects which alter the asteroid’s orbit (Carruba et al., 2025), such applications highlight the prospects of AI in the field of planetary science. Henceforth, to develop a deeper understanding of the potential and applications of ML, below is a typical AI workflow.

Typical AI workflow

A typical workflow for an AI model involves an initial step of selecting a model suitable for your goals (Figure 2). Data format, quality of the data, static or dynamic features of interest, etc can influence the choice of AI model or techniques. Data preparation steps, like normalizing the data i.e. scaling the data from [-1,1] values, prevents dominance of any one feature in the data and stabilizes the model training process.

Furthermore, parameters or hyperparameters are selected depending on the complexity of the model. While more complex models; deep neural networks or Vision Transformers will need hyperparameter adjustment to maximize performance, simpler models mainly rely on predefined weights or fixed rules. Likewise, a model architecture shall be established as per the data and targets. One example is the usage of the Faster-R-CNN - a robust and high accuracy yielding model which can be employed to train on high-resolution labelled images to perform object-detection tasks like identifying craters.

In scientific use cases, the workflow often encompasses actual data that must be separated into a training set, validation set (to optimize the hyper-parameters) and a test set, completely independent from the training. To evaluate “how well” the model has learnt from the training dataset, accuracy, precision, recall, F1-score, and intersection-over-union (IoU) are the most popular statistics. Subsequently, model predictions can help in developing an understanding of the potential areas for fine-tuning and refining the model for the use case. Henceforth, fine-tuning the model is another crucial step.

Figure 2: A typical AI workflow

Potential of AI

A successful application of ML in planetary science can be driven by a collaboration of scientists and ML experts. Scientists (astronomers, geologists, planetary scientists etc.) are arguably more equipped to answer science-based questions like what can be called a crater and conversely, ML experts may be more adept at assessing data preparation techniques to eradicate noise. The field of planetary sciences encompasses themes like anomaly detection, simulation and surface modeling, atmospheric studies, gravitational behavior and its effects on planets and smaller bodies, instrumentation and spacecraft design etc. which necessitates such collaborations for the optimum result. In recent years, Large Language Models (LLMs) have had a significant paradigm shift in AI applications due to their understanding of patterns acquired through their vast pre-training phase. For time series analysis, image classification, and pattern identification tasks common in planetary sciences, LLMs can significantly streamline workflows by reducing the need for specialized preprocessing steps.

Given the enormous data from missions and observational surveys, and the numerous applications of planetary sciences, it is the need of the hour to produce workflows that not only automates but helps in an objective/standard decision making for problem statements of planetary sciences. The Europlanet Machine Learning Working Group does exactly this by sharing the latest techniques, tools, and applications and opens doors for people who want to apply these robust techniques.

References

- Rich, E. (2019). Artificial Intelligence 3E (Sie) (Vol. 63, No. 4). Tata McGraw-Hill Education.

- Moussaoui, S. et.al. (2008) On the decomposition of Mars hyperspectral data by ICA and Bayesian positive source separation Neurocomputing for Vision Research; Advances in Blind Signal Processing, 71, 2194-2208, http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.neucom.2007.07.034

- Carruba, V. et al. (2025). Vision Transformers for identifying asteroids interacting with secular resonances. Icarus, 425, 116346. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.icarus.2024.116346

- D’Amore, M., & Padovan, S. (2022). Chapter 7 Automated surface mapping via unsupervised learning and classification of Mercury Visible–Near-Infrared reflectance spectra. In J. Helbert, M. D’Amore, M. Aye, & H. Kerner (Eds.), Machine Learning for Planetary Science (pp. 131–149). Elsevier. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-818721-0.00016-1

- Pletl, A. et.al. (2023). Spectral Clustering of CRISM Datasets in Jezero Crater Using UMAP and k-Means. Remote Sensing, 15(4), Article 4. /10.3390/rs15040939

- Zhang, D. et al. (2021). The AI Index 2021 Annual Report (No. arXiv:2103.06312). arXiv. /10.48550/arXiv.2103.06312

How to cite: Kacholia, D., Verma, N., D’Amore, M., Angrisani, M., Frigeri, A., Schmidt, F., Carruba, V., Hatipoğlu, Y. G., Roos-Serote, M., Smirnov, E., Sassarini, N. A. V., Solmaz, A., Oszkiewicz, D., and Ivanovski, S.: Artificial Intelligence in Planetary Science and Astronomy: Applications and Research Potential, EPSC-DPS Joint Meeting 2025, Helsinki, Finland, 7–13 Sep 2025, EPSC-DPS2025-1467, https://doi.org/10.5194/epsc-dps2025-1467, 2025.

How to cite: Smirnov, E.: Open-source large language models in astronomical data classification: applications and benchmarking, EPSC-DPS Joint Meeting 2025, Helsinki, Finland, 7–13 Sep 2025, EPSC-DPS2025-226, https://doi.org/10.5194/epsc-dps2025-226, 2025.

Asteroid families are groups of asteroids formed by a collision or fission event. Some asteroid families interact with secular resonances. Because of planetary perturbations, the pericenter and nodes of planets and asteroids precess with frequencies g and s. When the precession frequency of the asteroid (g) is close to that of Saturn (g6), or g-g6≈0, the ν6 resonance occurs.

Figure (1): The location of main secular resonances in the (a, sin(i)) domain.

Contrary to mean-motion resonances, secular resonances cannot be easily identified in a proper elements' 2-D domains. To identify if an asteroid is in a secular resonance, we need to investigate the time behavior of its resonant argument. With over 8 million asteroids predicted to be discovered by the Vera C. Rubin Observatory, traditional visual analysis of arguments will no longer be feasible.

Figure (2): Examples of resonant arguments for asteroids circulating, alternating phases of circulation and libration, and in libration states.

The first deep learning approach for identifying asteroids interacting with secular resonance was introduced in Carruba et al. (2021), with a multi-layer perceptron model. This is a five-step process:

1. We integrate the asteroid orbits under the gravitational influences of all planets.

2. We compute the time series of the resonant argument.

3. Images of these time series are obtained for each asteroid.

4. The model is trained on a set of labeled image data.

5. The model predicts the labels for a set of test images.

Carruba et al. (2022) applied Convolutional Neural Networks (CNN) for the classification of large databases of images and regularization techniques for correcting overfitting. In Carruba et al. (2024), digitally filtered images of resonant arguments were used to enhance the performance of CNNs. Finally, in Carruba et al. (2025), there was the first application of Vision Transformers.

Convolutional neural networks, or CNNs, are a neural network model originally designed to work with two-dimensional picture data. Their name derives from the convolutional layer. Convolution is a linear procedure involving the multiplication of a two-dimensional array of weights with an input array. The result of applying the filter is a two-dimensional array: the feature map. Three of the most commonly used CNN models are the VGG (Simonyan & Zisserman 2014), Inception (Szegedy et al. 2015), and the Residual Network, or ResNet (He et al. 2015).

Figure (3): An example of the application of Vision Transformers to the analysis of an image.

The Vision Transformer architecture for classifying images of resonant arguments was first applied in Carruba et al. (2025). The ViT model is based on the Transformer architecture (Vaswani et al. 2017), and it applies the Transformer architecture directly to image data, without the need for CNNs. In the ViT approach, an input image is split into fixed-size patches, usually 1/10 of the image size, which are then linearly embedded and fed into the Transformer encoder. The Transformer encoder consists of a series of Transformer blocks, which are made of two parts:

a. Self-Attention Mechanism: This allows the model to weigh the importance of different images for ViT, in a sequence relative to each other, enabling it to capture contextual relationships regardless of their distance in the input sequence.

b. Feed-Forward Neural Network: After the self-attention step, the output is passed through a feed-forward network, which applies transformations to the data independently for each position in the sequence.

Multiple transformer blocks can be stacked to form a complete Transformer model, allowing it to capture long-range dependencies and global information within the image. Two key hyperparameters in our model are:

1. num_layers: The number of Transformer blocks.

2. num_heads: The number of attention heads in the Multi-Head Attention layer.

We applied CNNs and ViT to three publicly available databases of images of resonant arguments for the ν6 (Carruba et al. 2022), g − 2g6 + g5 (Carruba et al. 2024a), and s − s6 − g5 + g6 (Carruba et al. 2024b).

Figure (4): Semi-logarithmic plot of the computational time for applying different methods of image classification.

The models' performance was superior when applied to images of filtered resonant arguments. ViT models outperformed CNNs in terms of running times (10 times faster!) and evaluation metrics, and their results are comparable to those of models produced by the new LLM approach of Smirnov (2024).

References

Carruba V., Aljbaae S., Domingos R. C., Barletta W., 2021, Artificial Neural Network classification of asteroids in the M1:2 mean-motion resonance with Mars, MNRAS, 504, 692.

V. Carruba, S. Aljbaae , G. Carita, R. C. Domingos, B. Martins, 2022, Optimization of Artificial Neural Networks models applied to the identification of images of asteroids' resonant arguments, CMDA, 134, A59.

V. Carruba, S. Aljbaae, R. C. Domingos, G. Carita, A. Alves, E. M. D. S. Delfino, Digitally filtered resonant arguments for deep learning classification of asteroids in secular resonances, 2024, MNRAS, 531, 4432-4443.

V. Carruba, S. Aljbaae, E. Smirnov, G. Carita, 2025, Vision Transformers for identifying asteroids interacting with secular resonances, Icarus, 425C 116346.

E. Smirnov, 2024, Fast, Simple, and Accurate Time Series Analysis with Large Language Models: An Example of Mean-motion Resonances Identication. ApJ , 966(2), 220.to asteroid resonant dynamics.

K. Simonyan and A. Zisserman. Very Deep Convolutional Networks for Large-Scale Image Recognition. ArXiv e-prints , page arXiv:1409.1556, September 2014.

C. Szegedy, W. Liu, Y. Jia, P. Sermanet, S. Reed, D. Anguelov, D. Erhan, V. Vanhoucke, and A. Rabinovich. Going deeper with convolutions. In Proceedings of the IEEE conference on computervision and pattern recognition , pages 1#9, 2015.

K. He, X. Zhang, S. Ren, and J. Sun. Deep residual learning for image recognition, 2015.

A. Vaswani, N. Shazeer, N. Parmar, J. Uszkoreit, L. Jones, A. N Gomez, L. Kaiser, and I. Polosukhin. Attention is all you need. arXiv preprint arXiv:1706.03762, 2017.

How to cite: Carruba, V., Aljbaae, S., Smirnov, E., and Caritá, G.: Vision Transformers for identifying asteroids interacting with secular resonances., EPSC-DPS Joint Meeting 2025, Helsinki, Finland, 7–13 Sep 2025, EPSC-DPS2025-58, https://doi.org/10.5194/epsc-dps2025-58, 2025.

The solar system is home to a diverse population of small celestial objects, including asteroids, comets, and meteoroids. Most small bodies in the solar system are found in two distinct regions, known as the Main Belt and the Kuiper Belt. However, certain small bodies, such as Near-Earth Objects (NEOs), have orbits that bring them into close proximity with the Earth and in some cases even collide with our planet. The goal of Impact Monitoring (IM)

is to assess the risk of collision of a small body with Earth. Understanding the potential risk posed by an asteroid and monitoring objects with a higher risk of collision is crucial for developing strategies for planetary defense. Since in the following years, vast amounts of data from astronomical surveys will become available, it is essential to implement a preliminary filter to determine which objects should be prioritized for follow-up using traditional IM methods.

We present a novel method for estimating the Minimum Orbit Intersection Distance (MOID) of a NEO based on artificial Neural Networks (NNs). The MOID is defined as the minimum distance between the two osculating Keplerian orbits of the Earth and the NEO as curves in the three-dimensional space; it is usually used as an indicator of the possibilities of a collision between the asteroid and the Earth, at least for the period during which the Keplerian orbit of the asteroid provides a reliable approximation of the actual orbit. Since Machine Learning (ML) has gained enormous popularity in the last few years and has been applied also to some Celestial Mechanics problems, we decided to try to estimate the MOID with a multilayer feedforward NN, which takes as input the coordinates of the asteroid at a specified epoch. After being trained on an artificial dataset of about 800,000 NEOs generated with NEOPOP, the NN has been tested on the currently known population of Near-Earth Asteroids. The network exhibits near-instantaneous predictions of the MOID and achieves a mean absolute error of approximately 10−3 on the test set. Fig. 1 shows the histogram of the actual and predicted values. The overestimation of the number of asteroids with a MOID value of 0 is due to the activation function used in the final layer of the NN, namely ReLU, which, by definition, outputs 0 for any negative input. By selecting a threshold value of 0.05, we transformed the regression problem into a classification problem. In particular, we consider the positive class the one formed by all asteroids with a predicted MOID exceeding the threshold. The resulting accuracy and false positive rate (FPR) are approximately 96.61% and 2.56%, respectively. To reduce false positives, we propose to prioritize testing with classical IM methods every object with a predicted MOID of 0.10 or less. In fact, we believe that ML should serve as an initial screening tool, enabling us to prioritize follow-up assessments using traditional IM methods when managing large volumes of data.

Figure 1: Histogram of the actual and predicted values

As a follow-up, we are testing the possibility of developing a NN capable of predicting the MOID starting from computable quantities derived directly from the observations. This would eliminate the need to calculate a preliminary orbit and apply the differential corrections procedure.

Specifically, we intend to use as input vector for the NN an attributable (α, δ, ˙ α, ˙δ ), together with the second derivatives of right ascension and declination. In fact, given m ≥ 3 optical observations (αi, δi) at times ti, it is easy to compute, with a quadratic fit of both angular variables separately, the quantities α, ˙ α, ¨α and δ, ˙δ, ¨δ. Although this task is more difficult, both in terms of data acquisition and NN training, the preliminary findings are promising.

In conclusion, this research represents a step forward in addressing the urgent need for effective IM techniques, partially answering the question of whether ML can serve as a preliminary filter for some orbit determination problems.

[1] Vichi, V., Tommei, G. Exploring the potential of neural networks in early detection of

potentially hazardous near-earth objects, Celest Mech Dyn Astron 137, 17 (2025).

How to cite: Vichi, V. and Tommei, G.: Exploring the potential of neural networks in early detection of potentially hazardous Near-Earth Objects, EPSC-DPS Joint Meeting 2025, Helsinki, Finland, 7–13 Sep 2025, EPSC-DPS2025-149, https://doi.org/10.5194/epsc-dps2025-149, 2025.

Understanding the surface and subsurface temperature distributions of small bodies in the Solar System is fundamental to thermophysical studies, which provide insight into their composition, evolution, and dynamical behavior [1,2]. Thermophysical models are essential tools for this purpose, but conventional numerical treatments are often computationally expensive. This limitation presents significant challenges, particularly for studies requiring high-resolution simulations or large-scale, repeated calculations across parameter spaces.

To overcome these computational bottlenecks, we developed ThermoONet -- a deep learning-based neural network designed to efficiently and accurately predict temperature distributions for small Solar System bodies [3,4]. ThermoONet is trained on results from traditional thermophysical simulations and is capable of replicating their accuracy with dramatically reduced computational cost. We apply ThermoONet to two representative cases: modeling the surface temperature of asteroids and the subsurface temperature of comets. Evaluation against numerical benchmarks shows that ThermoONet achieves mean relative errors of approximately 1% for asteroids and 2% for comets, while reducing computation time by over five orders of magnitude.

We test the ability of ThermoONet with two scientifically compelling yet computationally heavy tasks. We model the long-term orbit evolution of asteroids (3200) Phaethon and (89433) 2001 WM41 using N-body simulations augmented by instantaneous Yarkovsky accelerations derived from ThermoONet-driven thermophysical modelling [3]. Results show that by applying ThermoONet, it is possible to employ actual shapes of asteroids for high-fidelity modelling of the Yarkovsky effect. Furthermore, we employ ThermoONet to simulate water ice activity of comets [4]. By fitting the water production rate curves of comets 67P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko and 21P/Giacobini-Zinner, we show that ThermoONet could be of use for the inversion of physical properties of comets that are difficult to achieve with traditional methods.