SB3

Observational investigations of comets

Co-organized by EXOA

Convener:

Nicolas Biver

|

Co-conveners:

Oleksandra Ivanova,

Emmanuel Jehin,

Cyrielle Opitom,

Martin Rubin

Orals THU-OB6

|

Thu, 11 Sep, 16:30–18:00 (EEST) Room Jupiter (Hall A)

Orals FRI-OB2

|

Fri, 12 Sep, 09:30–10:30 (EEST) Room Jupiter (Hall A)

Orals FRI-OB3

|

Fri, 12 Sep, 11:00–12:30 (EEST) Room Jupiter (Hall A)

Orals FRI-OB4

|

Fri, 12 Sep, 14:00–16:00 (EEST) Room Jupiter (Hall A)

Posters THU-POS

|

Attendance Thu, 11 Sep, 18:00–19:30 (EEST) | Display Thu, 11 Sep, 08:30–19:30 Finlandia Hall foyer, F144–165

Thu, 16:30

Fri, 09:30

Fri, 11:00

Fri, 14:00

Thu, 18:00

In the context of the Rosetta mission and missions to small bodies including Comet Interceptor, and international observing campaigns of bright comets such as 12P/Pons-Brooks, C/2023 A3 (Tsuchinshan-ATLAS), C/2024 G3 (ATLAS), we solicit presentations on recent investigations.

The session will present results of optical, infrared or radio observations of comets and

active bodies obtained from ground-based telescopes, space observatories such as JWST, as

well as recent results from in-situ measurements from space missions.

Session assets

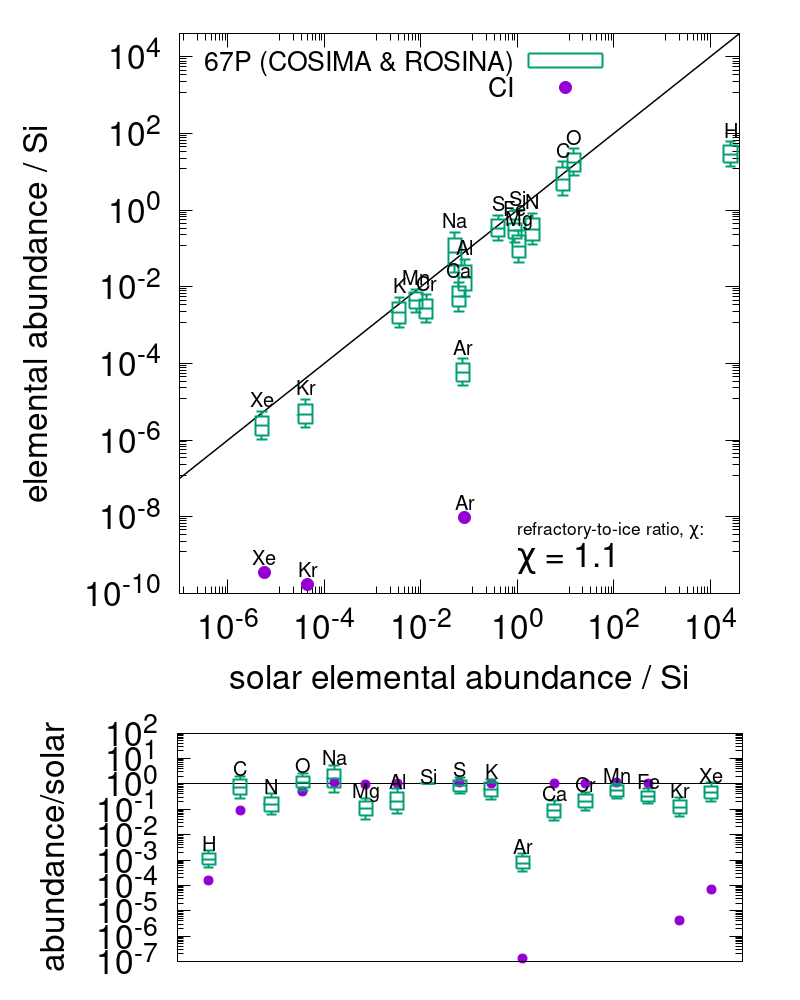

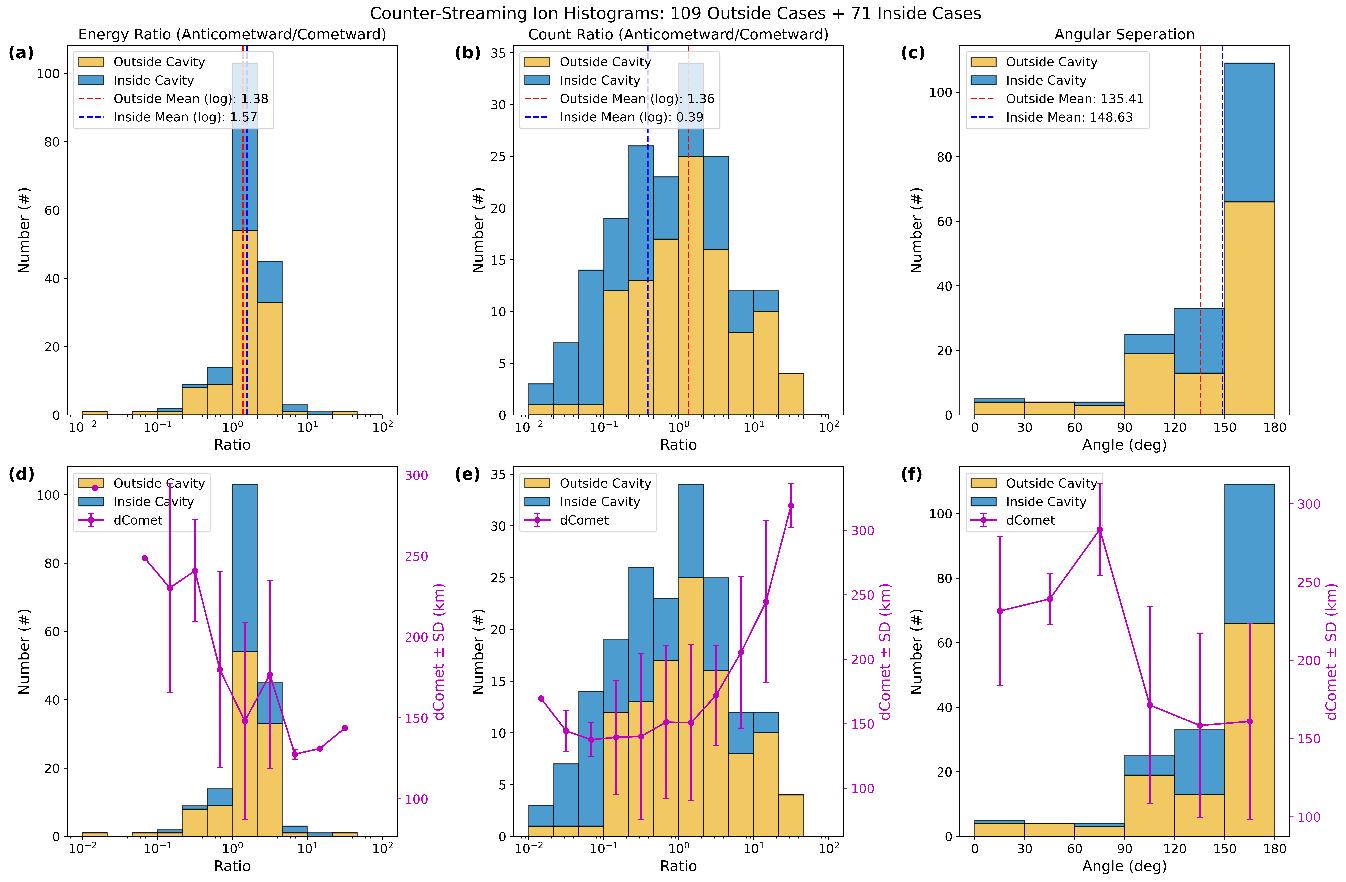

Lessons from comet 67P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko

16:30–16:42

|

EPSC-DPS2025-1696

|

On-site presentation

16:42–16:54

|

EPSC-DPS2025-894

|

Virtual presentation

16:54–17:06

|

EPSC-DPS2025-1257

|

ECP

|

On-site presentation

17:06–17:18

|

EPSC-DPS2025-1556

|

On-site presentation

17:18–17:30

|

EPSC-DPS2025-1944

|

On-site presentation

17:30–17:42

|

EPSC-DPS2025-867

|

On-site presentation

17:42–18:00

Presentations of posters

Nucleus and coma properties of comets

09:30–09:42

|

EPSC-DPS2025-1233

|

On-site presentation

The Nucleus of Comet 28P/Neujmin 1: Lightcurves, Rotation Period, and Phase Function

(withdrawn)

09:42–09:54

|

EPSC-DPS2025-941

|

ECP

|

On-site presentation

09:54–10:06

|

EPSC-DPS2025-1414

|

On-site presentation

10:06–10:18

|

EPSC-DPS2025-1777

|

On-site presentation

10:18–10:30

|

EPSC-DPS2025-824

|

On-site presentation

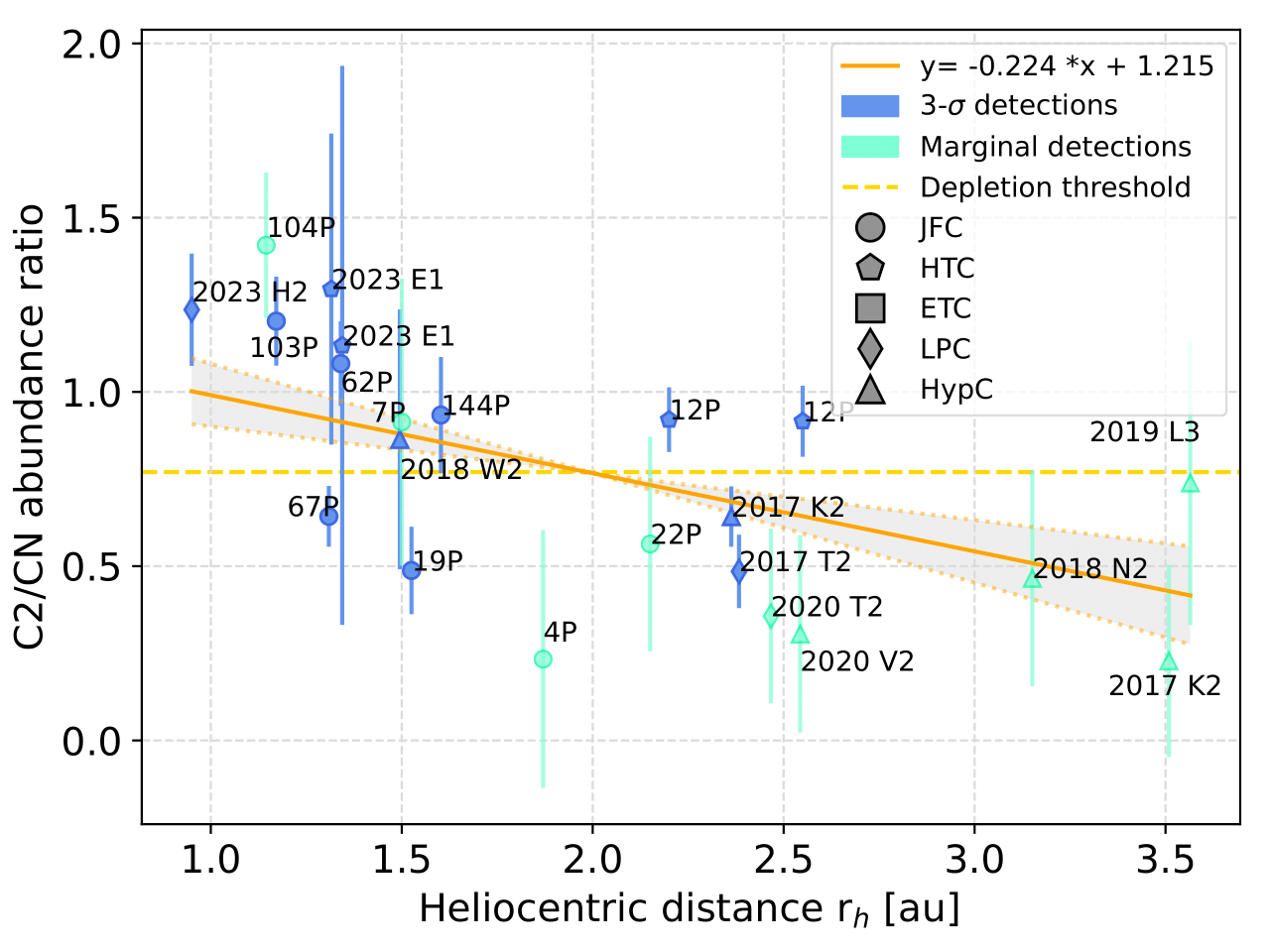

Distant activity and monitoring of comets

11:00–11:15

|

EPSC-DPS2025-1691

|

ECP

|

On-site presentation

11:15–11:27

|

EPSC-DPS2025-721

|

On-site presentation

11:27–11:39

|

EPSC-DPS2025-1155

|

On-site presentation

11:39–11:51

|

EPSC-DPS2025-972

|

ECP

|

On-site presentation

11:51–12:03

|

EPSC-DPS2025-830

|

ECP

|

On-site presentation

12:03–12:15

|

EPSC-DPS2025-1785

|

On-site presentation

12:15–12:27

|

EPSC-DPS2025-1066

|

ECP

|

On-site presentation

12:27–12:30

Discussion

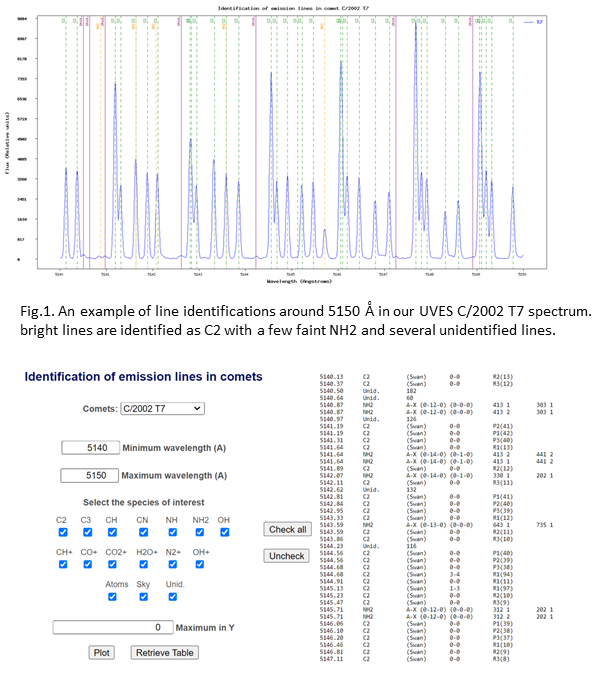

Recent comets and coma composition

14:00–14:12

|

EPSC-DPS2025-917

|

ECP

|

Virtual presentation

14:12–14:24

|

EPSC-DPS2025-1065

|

ECP

|

On-site presentation

14:24–14:36

|

EPSC-DPS2025-74

|

ECP

|

On-site presentation

14:36–14:48

|

EPSC-DPS2025-1381

|

On-site presentation

Long-term activity and outburst of comet 12P/Pons–Brooks from broad-band photometry

(withdrawn)

14:48–15:00

|

EPSC-DPS2025-1309

|

ECP

|

On-site presentation

15:00–15:12

|

EPSC-DPS2025-540

|

On-site presentation

15:12–15:24

|

EPSC-DPS2025-801

|

Virtual presentation

15:24–15:36

|

EPSC-DPS2025-1102

|

Virtual presentation

15:36–15:48

|

EPSC-DPS2025-1172

|

ECP

|

Virtual presentation

iSHELL Observations of Halley-Type Comet 13P/Olbers: Investigating Primary Volatile Composition in a Rare Dynamical Class.

(withdrawn)

15:48–16:00

Open discussion

F145

|

EPSC-DPS2025-1635

|

ECP

|

On-site presentation

F146

|

EPSC-DPS2025-1142

|

On-site presentation

F148

|

EPSC-DPS2025-869

|

ECP

|

On-site presentation

F149

|

EPSC-DPS2025-132

|

On-site presentation

F150

|

EPSC-DPS2025-78

|

On-site presentation

F151

|

EPSC-DPS2025-1175

|

ECP

|

On-site presentation

F152

|

EPSC-DPS2025-628

|

On-site presentation

F153

|

EPSC-DPS2025-495

|

On-site presentation

F154

|

EPSC-DPS2025-1474

|

ECP

|

On-site presentation

F155

|

EPSC-DPS2025-1523

|

ECP

|

On-site presentation

F156

|

EPSC-DPS2025-1076

|

On-site presentation

F157

|

EPSC-DPS2025-1342

|

On-site presentation

F158

|

EPSC-DPS2025-1478

|

On-site presentation

F159

|

EPSC-DPS2025-54

|

On-site presentation

F160

|

EPSC-DPS2025-1646

|

ECP

|

On-site presentation

F161

|

EPSC-DPS2025-1369

|

ECP

|

On-site presentation

F162

|

EPSC-DPS2025-206

|

On-site presentation

F163

|

EPSC-DPS2025-1182

|

ECP

|

On-site presentation

F164

|

EPSC-DPS2025-1122

|

On-site presentation

F165

|

EPSC-DPS2025-694

|

On-site presentation